A few weeks ago I posted about the Art House on Shattuck, a flash-backing and welcoming and stimulating living room of the Sixties.

Photo: https://peoplesbarknewsberkeley.wordpress.com/2015/08/25/great-events-coming-to-art-house-gallery-cultural-center/

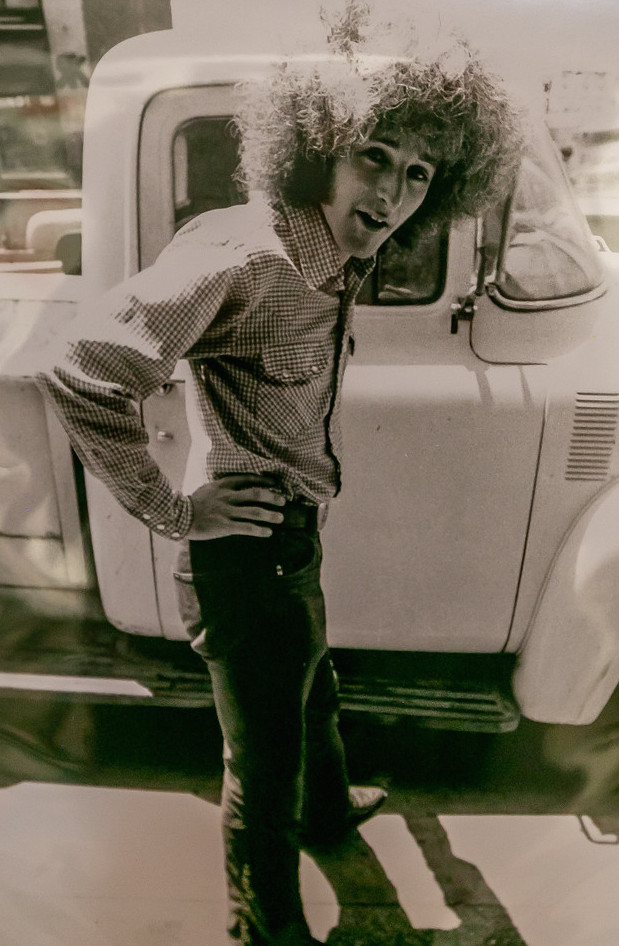

Harold Adler is the bright light behind the Art House. Some of the highlights of his life and work are recounted below. It would be a Herculean task to recount them all. He is another of Berkeley’s polymaths, a person of wide-ranging knowledge, learning, and cultural experience.

He was born in Oakland in the mid 1940s. His father was a shipyard worker who became a scrap iron dealer. His mother held down the home front and did work for her uncle Morris Gelfand’s Bargain House.

Adler’s mother’s father Baruch escaped a Russian pogrom and came to New York. Baruch’s father Josef was a rabbi in Kiev who was killed in the organized massacre.

Music

Young Harold liked to sing.

He sang in the Skyline High School choir and on the high holidays in the choir at Temple Beth Abraham.

His first musical instrument was the accordion.

Dick Contino was his hero. Contino, born in Fresno, studied accordion primarily with Angelo Cognazzo from San Francisco.

Contino appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show a record 48 times.

He was drafted during the Korean War. He escaped from pre-induction barracks at Fort Ord and was AWOL for more than a week. He surrendered and was convicted of draft evasion, fined ten thousand dollars, sentenced to and served six months in prison. After prison he was inducted, served his time, and was eventually pardoned by President Truman. This was a little speed bump in his career.

Adler’s parents took him to hear Contino at the Italian Village, 901 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco. A few years later, in 1953, the restaurant was all but destroyed by a fire.

Adler quit the accordion, briefly took piano lessons, and quit the lessons. He didn’t like the rigidity of reading music. Like others who play by ear, his path was to discern a song’s key, and then the chord progressions, and then improvise around that, often playing along with records.

In high school, Adler led a band, the Apollos. He played piano and was the lead singer. The band featured a trumpet, sax, bass, drum, and guitars and played 1950s rock and roll. “The problem with a band was that you’d learn a song, one of the band members would leave,and you’d have to break the new guy in learning the songs. And then somebody else would leave. You were always re-learning the same songs.” The band played at the Skyline High School senior dinner in 1963.

Hobbies

Adler grew up in a time when boys had hobbies. His first boyhood hobby was stamp collecting.

I don’t know what the rabbit is doing in the photo. Stamp-collecting got boring.

Then came rocks and minerals. He loved walking and looking for cool rocks. He found an Indian arrowhead in Leona Lodge. And then there was photography. His father taught him to use a camera and light meter. His mother taught him to use the dark room. They had a dark room in the rumpus room – not a term you hear every day anymore. Do you remember – recreation room, rec room, play room, ruckus room? Adler has a darkroom to this day.

After graduating from Skyline High School in 1963, he enrolled at Oakland City College.

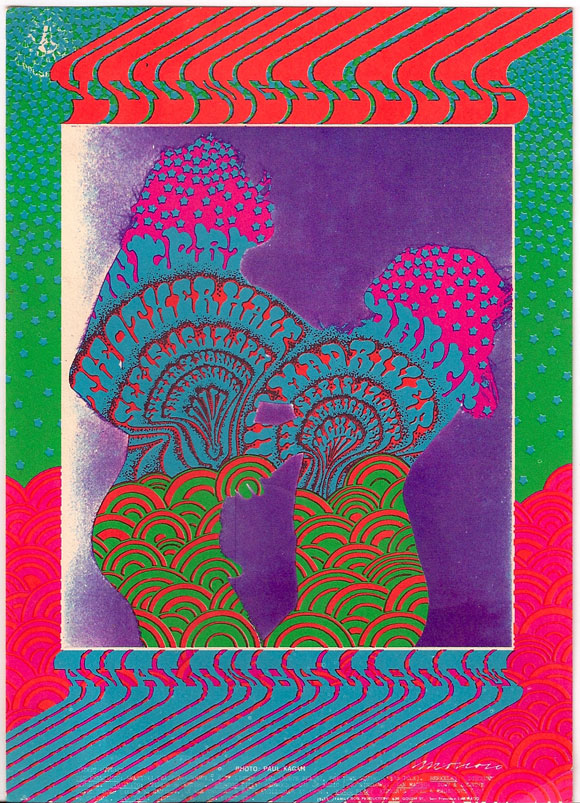

He came to know and be greatly influenced by psychedelic photographer Paul Kagan (University of California at Berkeley, Class of 1965).

Kagan often worked with the Family Dog, a commune on Pine Street, San Francisco, that hosted dances and concerts.

Chet Helms moved into the house and formed Family Dog Productions, which went on to produce many important early psychedelic rock concerts.

From Kagan, Adler learned about special effects and screens.

Harold and the Draft

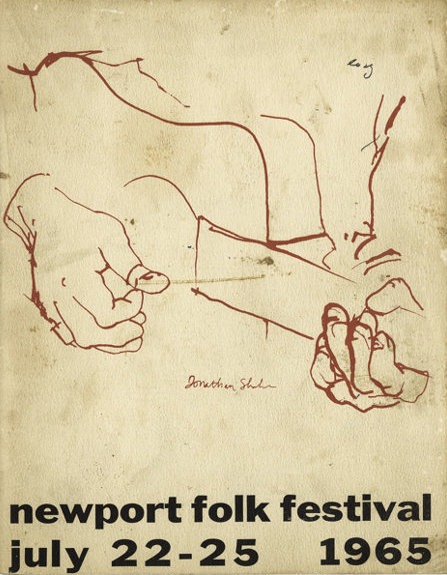

In 1965, Adler set out a drive across the country to the Newport Folk Festival to hear Bob Dylan.

There were rumors that Dylan was going to play electric.

Adler drove his turquoise 1956 Chevrolet. The photo above is not the actual car but you get the picture – a sweet ride. This was a super important trip for Adler. He had his Yashika camera with him and was going to capture a Very Important Moment.

The and a friend made it across the country in two and half days, but near the end of the trip had a blow-out in the front tire. He was hospitalized for three days. He didn’t make it to Newport.

P.S. On Saturday, July 24, Dylan performed three acoustic songs, “All I Really Want to Do”, “If You Gotta Go, Go Now”, and “Love Minus Zero/No Limit”, at a Newport workshop.

On the night of Sunday, July 25, Dylan’s appearance was between two traditional folk acts, Cousin Emmy and the Sea Island singers. Dylan played electric. His band included two musicians who had played on his recently released single “Like a Rolling Stone”: Mike Bloomfield on lead guitar and Al Kooper on organ. Paul Butterfield Blues Band, bassist Jerome Arnold and drummer Sam Lay played with the band, Newport, as did Barry Goldberg on piano.

Eight month later he received his notice for a physical examination by Selective Service. His mother suggested that he take a letter from his doctor saying that he had suffered injuries in a serious automobile accident. He did. On the basis of the letter he was rejected for military service. He missed Dylan but he missed Vietnam too.

Folk Music

Adler was drawn to Berkeley’s significant folk music scene, especially at the Cabale Creamery, 2504 San Pablo. He was in the first row the night the Chambers Brothers performed “Time” but he didn’t have his camera.

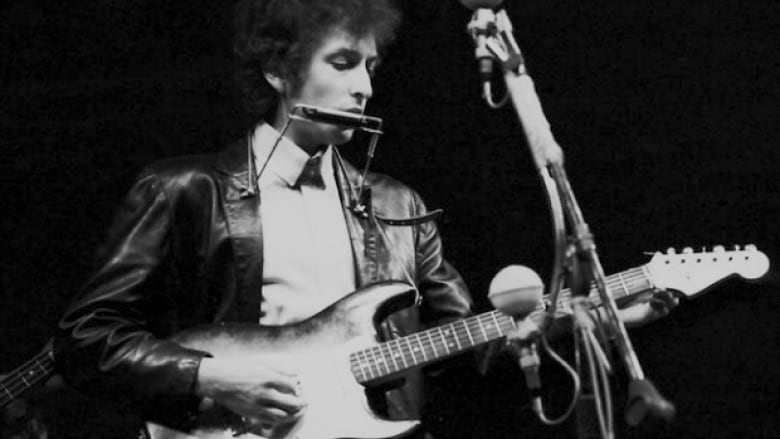

Once Adler heard Bob Dylan, he bought a Martin D21 guitar from Jon Lundberg. He played Dylan covers on the guitar on Telegraph for fun, not money.

Through a wrong number call intended for folk singer Perry Letterman, Adler was invited to play one night at the Jabberwock, a folk club on Telegraph.

Through a wrong number call intended for folk singer Perry Letterman, Adler was invited to play one night at the Jabberwock, a folk club on Telegraph.

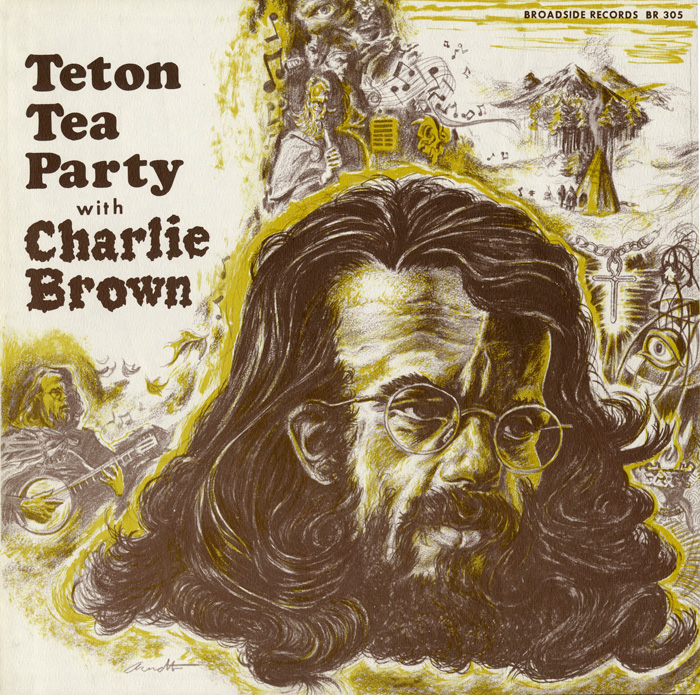

In the mid 1960s, Adler started attending a singing circle with Malvina Reynolds and local folk musicians. It was known as a “Teton Tea Party.” A joint was passed around the circle as was the chance to lead the group in a song. The concept may have been brought to Berkeley by “Charlie Brown” Artman, often referred to as Berkeley’s first hippie.

Adler saw Bob Dylan perform at the Berkeley Community Theater and engineered himself into the after-party with songwriter Kevin Farrell’s at a house on Shattuck and Oregon Street (now a car lot). It wasn’t a big crowd – a few members of the Jim Kweskin Jug Band. Adler talked with Dylan for three or four minutes, who was about to bring The Band in as his band.

Street Photography

Adler eventually dropped out from Oakland City to photograph full-time. He was getting good grades in speech and psychology, but was bored in the classroom with the world changing only a few miles away in Berkeley. He wanted to be doing, not studying. He immersed himself as a photographer of the political and counterculture Berkeley and Bay Area scene.

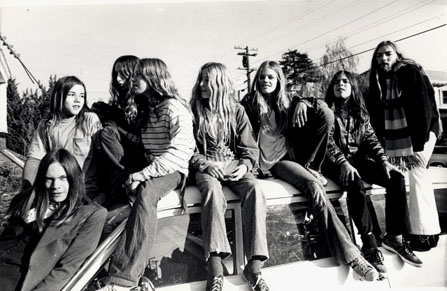

He photographed street people in Berkeley, including the Red Rockets/Mini Mob, a group of young teens who spent their lives on Telegraph between Haste and Dwight. The Telegraph Avenue scene and the “Telegraph Hilton” was of special interest to Adler.

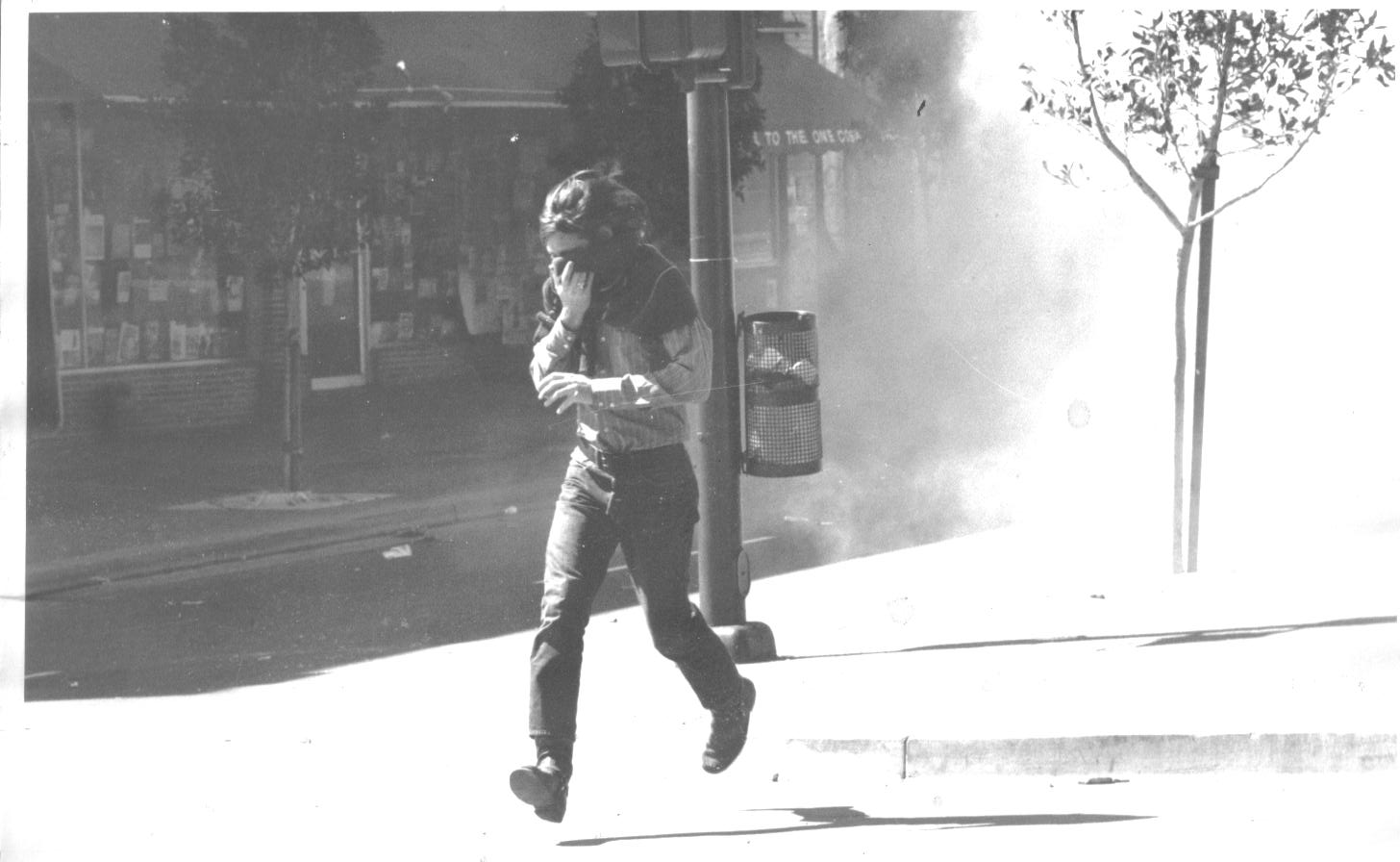

His first political shoot was a Vietnam Day Committee march to Oakland. People’s Park in 1969 was his baptism in photographic fire.

He prided himself as a good runner. He ran the 50-yard dash and the quarter mile in high school. He also ran at Oakland City. One day at lunch he got dosed with LSD. He went to track tripping but was confident – “I can do this.” He ran the quarter mile in his personal best time. “Nice run, Adler” his coach said.

Anyway – Running away from riots was his usual defense mechanism. His one injury came when a tear gas canister that looked like a dud exploded in his face.

There were open poetry readings at Shakespeare and Company on the corner of Dwight and Telegraph every Sunday. Andy Clausen, Richard Krech, John Oliver Simon, Julia Vinograd, Ron Silliman, John Grube and others read. Adler read his poetry and tape recorded the readings; his tapes are in the KPFB archives.

Adler worked in different capacities for Max Scherr and the Berkeley Barb.

He sold his photos to the Barb, delivered the paper in his station wagon, and developed headlines made with a label-maker in the darkroom, and he shot photos. Max paid $5 a photo, $10 for a cover. It doesn’t sound like much, but things didn’t cost much.

After the Barb, Adler shot photos for The Night Times, a Bay Area entertainment paper. Jim Blodgett was the managing editor. He had been student body president at Berkeley High and while at Cal was the managing editor of the Daily Californian. Joel Selvin wrote for the paper. Paul Kagan also sold them photos.

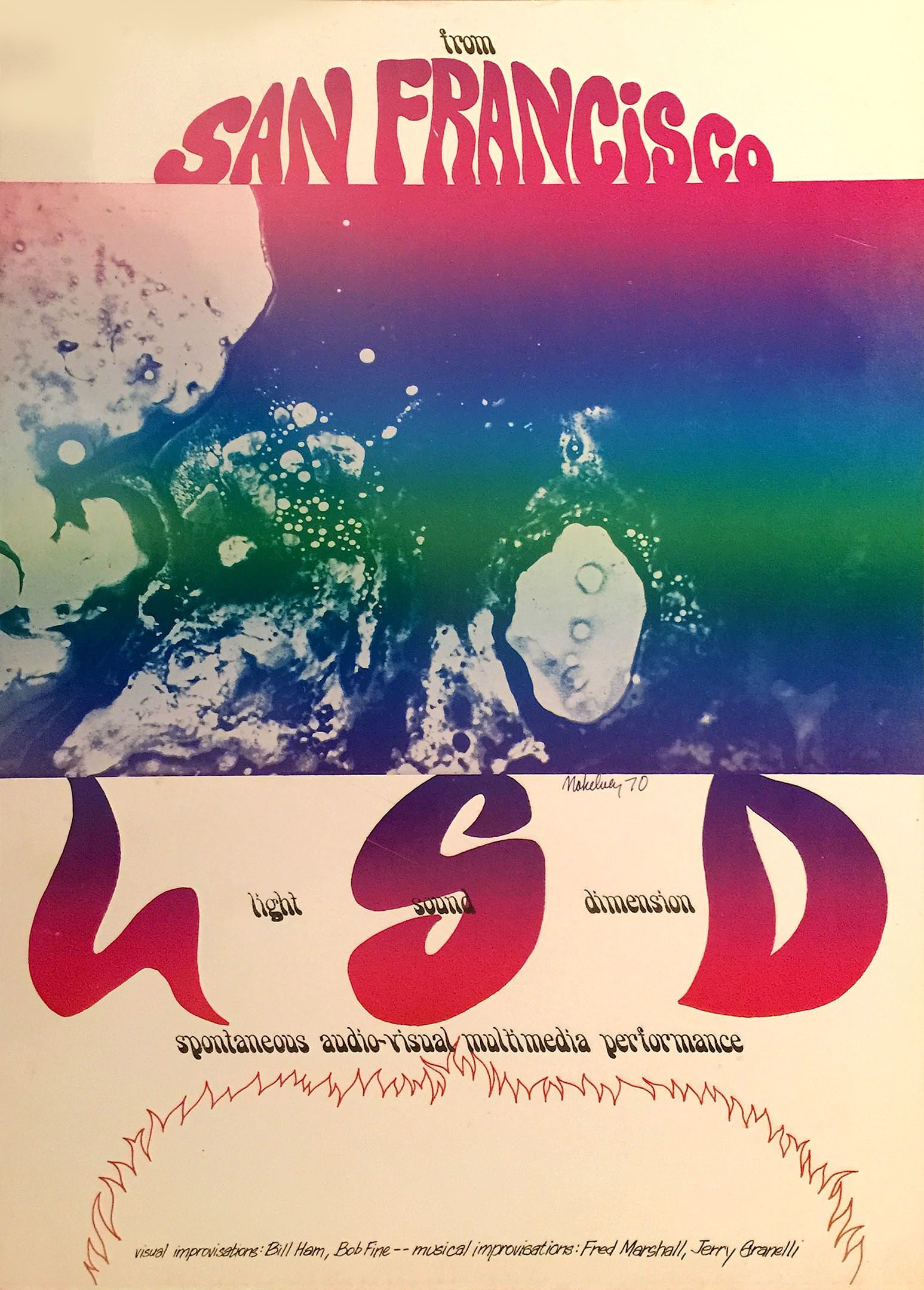

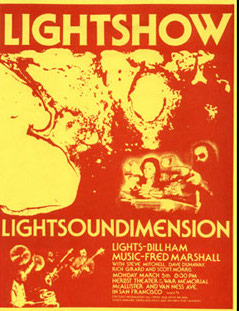

Light Shows

Light Shows

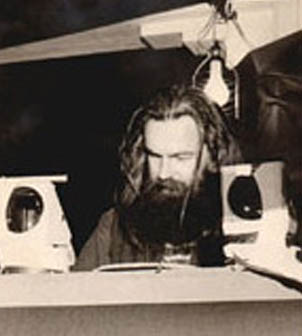

Harold Adler starting doing light shows as New Looney Toones Light Circus from 1967 until 1970. Mark Jacobson wrote about the Light Circus in the April 12, 1976 New York Magazine: “Harold asked me to ‘do liquids.’ ‘Doing liquids’ meant squirting some food coloring into a bowl and swishing it around in time to the music.”

Adler had learned at the feet of Bill Ham, the godfather of psychedelic light shows.

Backstage Light Sound Dimension Theatre 1968

top: Fred & Beverly Marshall, Noel Jewkes, Jerry Granelli

bottom: Bill Ham and Bob Fine.

Through a friend or friend of a friend, Adler got to meet Ham at the Avalon Ballroom. Adler asked if he could watch, or even try. Ham told him to watch what others were doing and then to try doing what they were doing. What a trip!

The same night he briefly met Janis Joplin. Before the show she was cursing a blue streak about a sore throat; she had a cold and her doctor told her she shouldn’t sing. Adler suggested tea with lemon. She said she tried that but it didn’t work. After the show Adler told her, “Man, you sounded great.” She said, “Thanks a lot, man.” That’s how it was then.

In 1968, Adler built The Psychedelic Pizza Machine. He stained clear plastic discs which he spun shining light through.

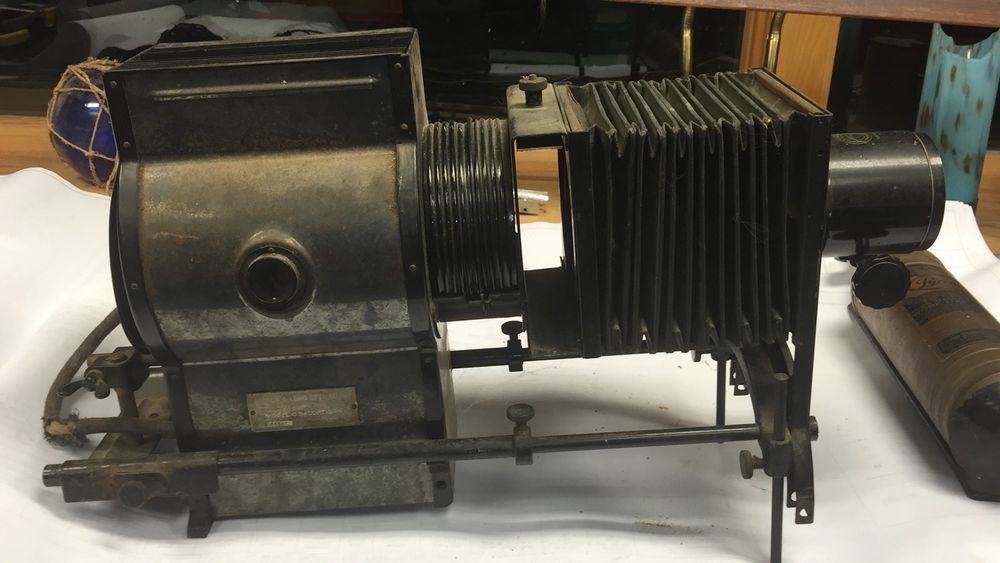

He used a thousand-watt quartz bulb installed in a lantern-light projector. His father helped with the installation of a large fan to cool the bulb and a small motor to turn the psychedelic pizza. Shown is a lantern projector identical to the one that Adler uses

He used a thousand-watt quartz bulb installed in a lantern-light projector. His father helped with the installation of a large fan to cool the bulb and a small motor to turn the psychedelic pizza. Shown is a lantern projector identical to the one that Adler uses

He also used chrystal spinners – two overhead projectors side by side with a spinning color wheel in front of both and a patterned chrystal plate with a bb glued in the center that also was spun by hand.

Also in 1968, Adler did a liquid projection light show for a poetry reading at a coffee shop on Grant Street in San Francisco. An employee of the nearby Condor Club – a strip club on Broadway – saw the light show and invited Adler to come talk to his boss at the Condor.

In an underground office at the Condor, a cigar-chomping manager from central casting, his feet on his desk, told Adler “Hey, kid, sit down.” “We hear you do light shows. Wanna do a light show for us.” Adler said sure and asked how much they paid. He offered Adler $50 a night to do his light show at the Condor.

For two Saturday nights, Adler did a light show called the Psychedelic Dance of Love at the Condor, projecting a liquid lights show onto a topless Carol Doda, then in her prime. Adler and Doda had a friendly conversation about his light show work. She said, “I really like what you do.” Adler said, “I like what you do too.”

He operated the projector from a spot very near the famous elevator piano upon which Doda made her entrance.

Digression: In November 1983, James “Jimmy the Beard” Ferrozzo, the club’s assistant manager, was having sex on the piano with dancer Theresa Hill on the piano when the piano accidentally rose to the ceiling, crushing him. The Janitor Angel Vicente discovered the two jammed against the ceiling when he got to work the next morning. Ferrozzo was dead but Hill survived.

Anyway – after two Saturday nights the Condor told Adler they wouldn’t need him anymore. They had a waiter in the club study how Adler did what he did, and so the Psychedelic Dance of Love continued without Adler. How’s that for a resume entry – he taught the Mafia how to do psychedelic light shows!

The same syndicate wanted to take over a club. Donovan’s Reef. on the Great Highway and offered Adler the job of doing light shows there. The neighbors didn’t like the idea of a Mafia club. It didn’t work out.

The same syndicate wanted to take over a club. Donovan’s Reef. on the Great Highway and offered Adler the job of doing light shows there. The neighbors didn’t like the idea of a Mafia club. It didn’t work out.

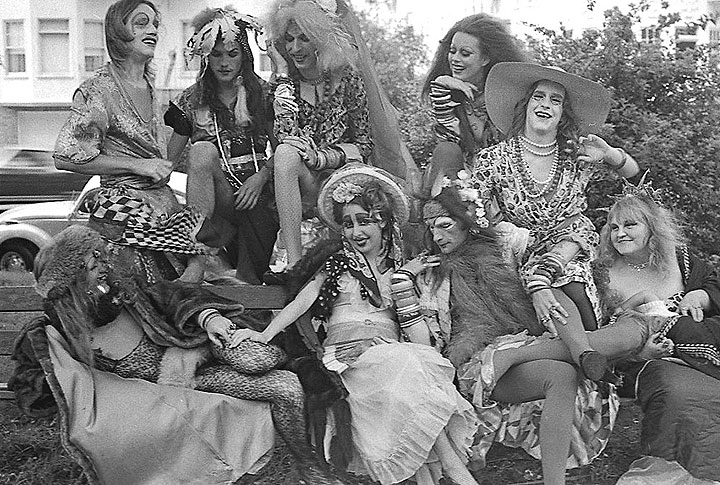

He did a memorable light show with the Cockettes, an avant garde hippie theater group founded by Hibiscus (George Edgerly Harris II) in the fall of 1969 with a group of hippie artists, men and women, who were living in Kaliflower, a commune in Haight-Ashbury, Hibiscus came to the commune because of their preference for dressing outrageously and proposed the idea of putting their lifestyle on the stage.

The show, Journey to the Center of Uranus, was at the Palace Theater. Adler went to the Palomar Observatory and bought slides of outer space that he mixed into his normal psychedelic light show. The Cockettes were light years ahead of their time. He found that they were not kind to each other.

From 1989 throught 2001 he put on 300 light shows as Liquid Sircus Delights or L.S.D. Visuals. He did over 300 raves and dance parties. He found the music “as boring as a washing machine.” The City came to understand the prominent role of Ecstasy and LSD and the regular overdoses in the raves, the pressure came. The rave scene slowed down considerably as fire marshals shut down venue after venue for lack of sprinkler systems and appropriate exits, plus the light show business changed with the advent of lasers and computer-generated images.

The Magnes Museum

Adler was drawn into the field of Seymour Fromer and the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, then housed in the former Burke mansion at 2911 Russell.

The Magnes was launched by happenstance.

Wandering through the Holmes used bookstore in Oakland, Fromer came across a 1894 Oakland high school yearbook with a picture of Judah L. Magnes, the first ordained rabbi from California. Fromer explored more and came to understand that the West’s Jewish history and traditions were richer than he had known.

After meeting Manees’ widow in Israel, Seymour and Rebecca Fromer decided to start a museum. It opened its doors in 1962.

Harold knew of Fromer as a fellow member of the congregation at Temple Beth Abraham when Adler was bar mitzvahed but he didn’t really get to know Fromer until Fromer’s daughter Marilyn Fromer suggested to Adler when they were both students at Oakland Junior College that he would enjoy meeting her parents. Adler met Fromer and his wife Rebecca and they all clicked.

Fromer was in the process of moving the huge collection from his office in the Parkway Theatre in Oakland to the first home of the Magnes in the Burke Mansion on Russell Street in Berkeley.

He hired Adler to work for the Magnes as the first employee – a handyman painting and cleaning, Fromer got Adler a job printing for the Jewish Welfare Federation in Oakland.

If Adler brought his own ink, he was allowed to print outside jobs there – small poetry books for street poets in Berkeley, leaflets, and posters.

Adler was inspired by Cantor Simon Cohen and he credits Beth Abraham rabbi Harold M. Schulweis as a strong influence with his sermons on social justice. Seymour and Rebecca Fromer were important in his life – they helped him through had times, and Adler came to think of Seymour as a second father.

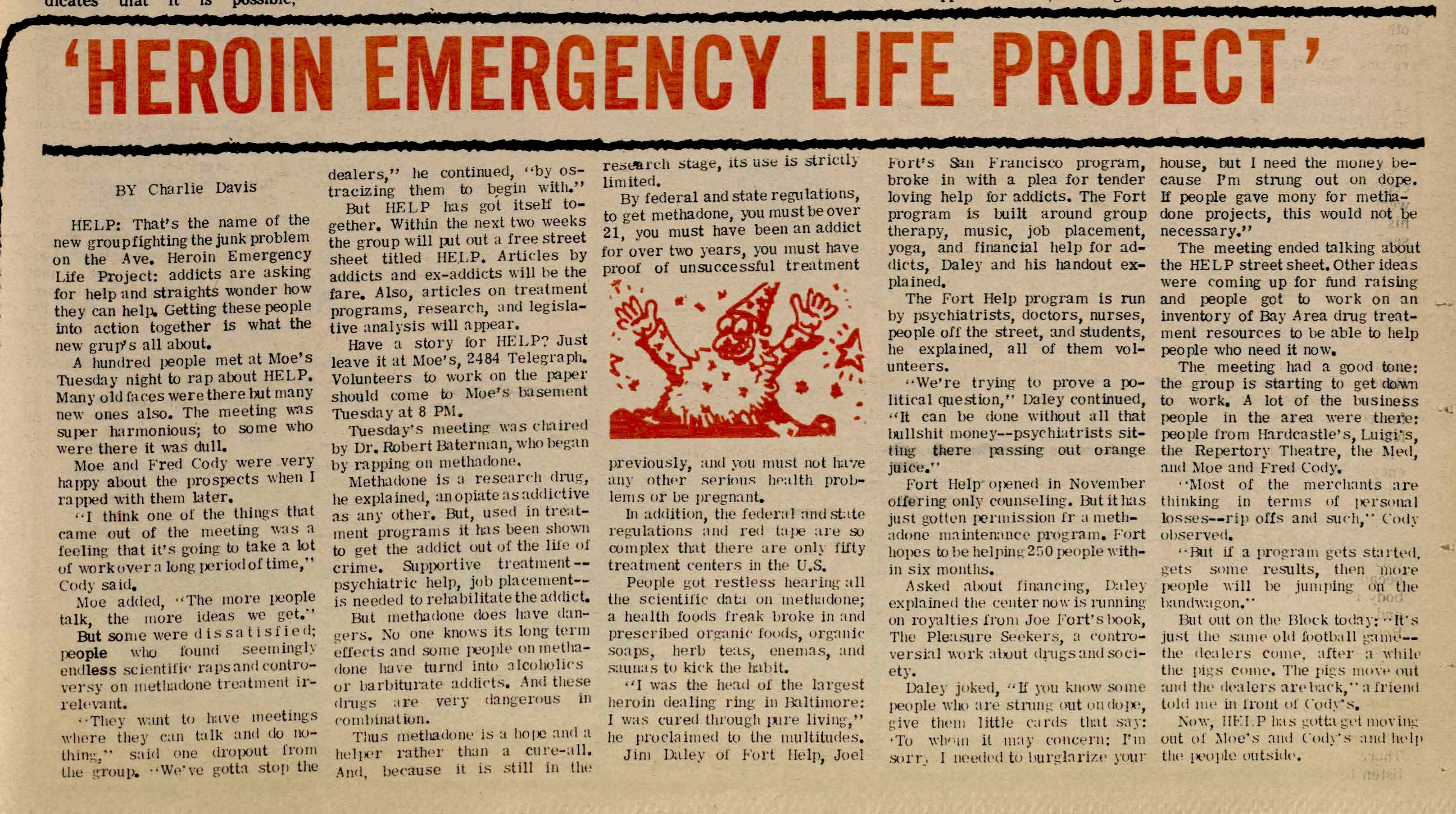

Heroin Emergency Life Project

Harold Adler threw himself into the Heroin Emergency Life Project after the death of his friend Sonya. She was bright, beautiful, smart – and a junkie. He was living on Folger Street at the time, across the street from 835 Folger where Commander Cody and his band lived for several months. She visited him there. She took him to a shooting gallery on High Street in Oakland. He had his guitar with him and played Dylan songs as people bought drugs and shot up. He was very frightened.

Three months later Sonya was stabbed to death in a drug deal gone wrong.

Adler wanted to do something about the heroin epidemic sweeping Telegraph and Berkeley. He had a vision for Berkeley’s heroin addicts – buy land in Marin, start a community there, and get the addicts out of Berkeley to Marin where they could kick heroin.

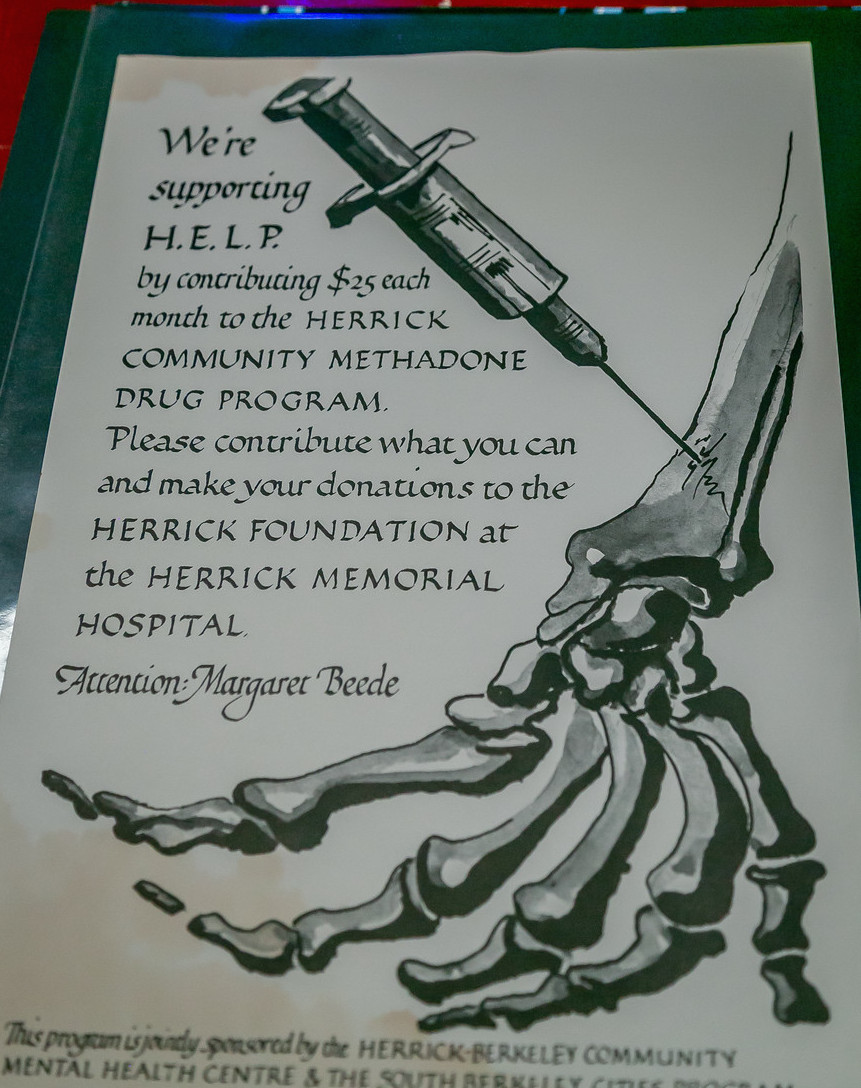

He joined with the HELP project. A large crowd — perhaps 100 people — attended the kick-off meeting at Moe’s Books. Among those hoping to get HELP off the ground were a sizable number of Telegraph merchants — Moe Moskowitz of Moe’s Books, Fred Cody of Cody’s Books, and “people from Hardcastle’s, Luigi’s, the Repertory Theatre, [and Caffe] Med,” according to the Barb.

Doctor Robert Batterman of Herrrick Hospital interjected himself in the meeting. He had a different idea. He was interested in the then-innovative use of methadone as maintenance treatment for heroin addiction.

Adler produced benefit concerts at Pauley for the project – Country Joe, Commander Cody, and Joy of Cooking. He interviewed people on Telegraph about drugs, posing as a writer for a street sheet on drugs. In fact, his interviews were fodder for Batterman and his methadone project.

In a meeting at Moe’s house, the project embraced Batterman and his methadone approach. Adler felt hijacked and betrayed. He said “Fuck you” and walked out.

The Living Theatre Benefit

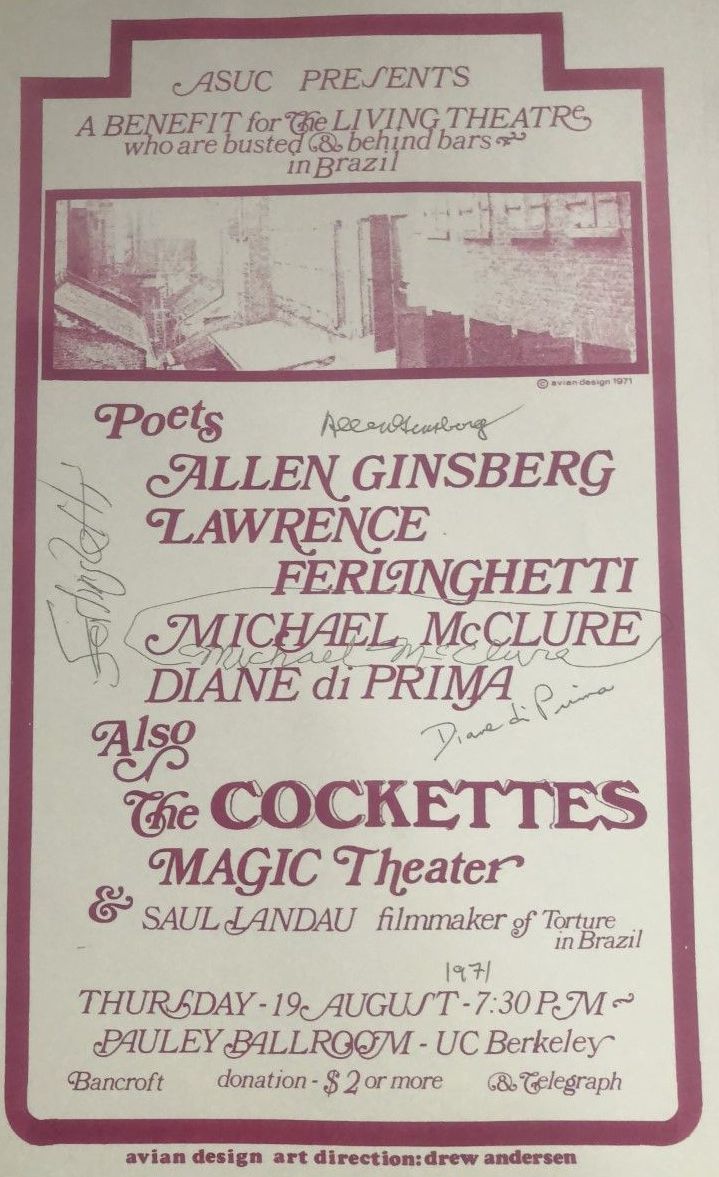

In 1971, Adler produced an enormously successful benefit for the Living Theatre, whose members had been arrested and were jailed in Brazil.

The Living Theater was an experimental theatre group founded in New York by Judith Malina and Julian Beck in 1947. During their stay in various villages and cities in Brazil, the Living Theatre observed the corruption in politics and society, and sought to advocate for change, freedom and justice. On July 1, 1971, members of the Living Theatre were arrested by the Brazilian Department of Political and Social Order for possession of marijuana.

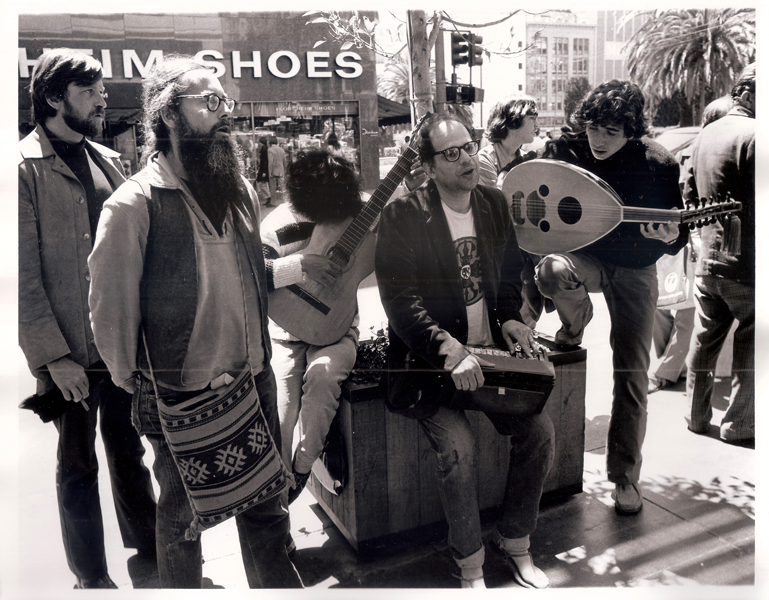

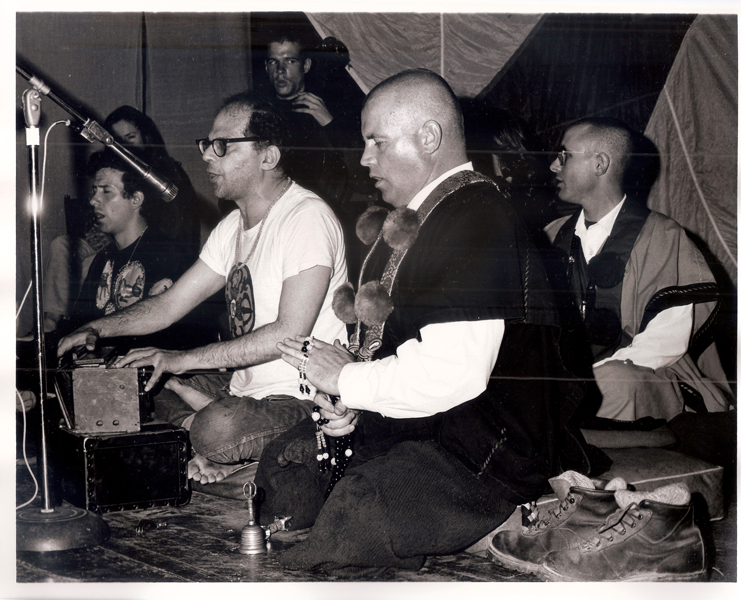

Allen Ginsberg led a benefit for the Living Theater at the Julian Theater in San Francisco on October 19, 1971. The mimes in the photo, taken in Union Square, are from the Julian Theatre. The Cockettes and members of the Magic Theatre performed. Ginsberg is playing a harmonium in the photo. Adler photographed the event for the Barb. There were no other still photographers there.

Adler then conceived of a benefit in Berkeley. Ginsberg was staying in a friend’s attic in Berkeley; a friend took Adler to meet him. They smoked a joint and Ginsberg, in addition to agreeing to perform, gave Adler the phone numbers of Diane de Prima, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Michael McClure, all Beat poets. Berkeley’s Magic Theater and the Cockettes also performed.

The benefit was held in Pauley Ballroom, which holds 1000 people. Every ticket was sold and 400 people were turned away. The benefit raised more than $2000 for the Living Theater’s Legal Defense Fund.

Studio 841

For a while, Adler tired to collaborate with Allen Michaan on a project called Studio 841. Michaan and Adler had different visions. Michaan focused on a movie theater, while Adler focused on a movie production facility with a sound stage, screening room, editing room and recording studio. He was beginning to attract musicians to rehearse and record there – Commander Cody, County Joe, Joy of Cooking

Adler had worked with film and video and several years. He and other filmmakers collaborated in the Cinema Workshop.

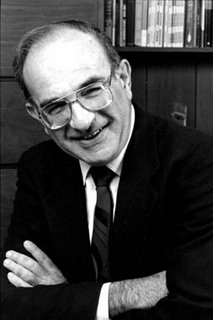

Saul Zaentz visited to see what Adler was up to. Several years later Zaentz would hit the big time with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

A few movies were shot there, including The Stewardesses. Adler was the stage manager for the scenes shot at the sound stage at 841 Gilman.

The “plot”? One night in the lives of a crew of Los Angeles-based stewardesses. The leading character is killed in a 30-story suicide leap, and the others simply indulge in drugs and sex. One of the girls befriends and beds a returning Vietnam combat soldier. Produced on a budget of just over $100,000, the film grossed $25 million in 1970

Things didn’t work out between Adler and Michaan. Their styles and goals did not match.

Michaan has gone on to a career in part devoted to old movie theaters. He runs the Alameda Point Antiques Faire and a successful auction house.

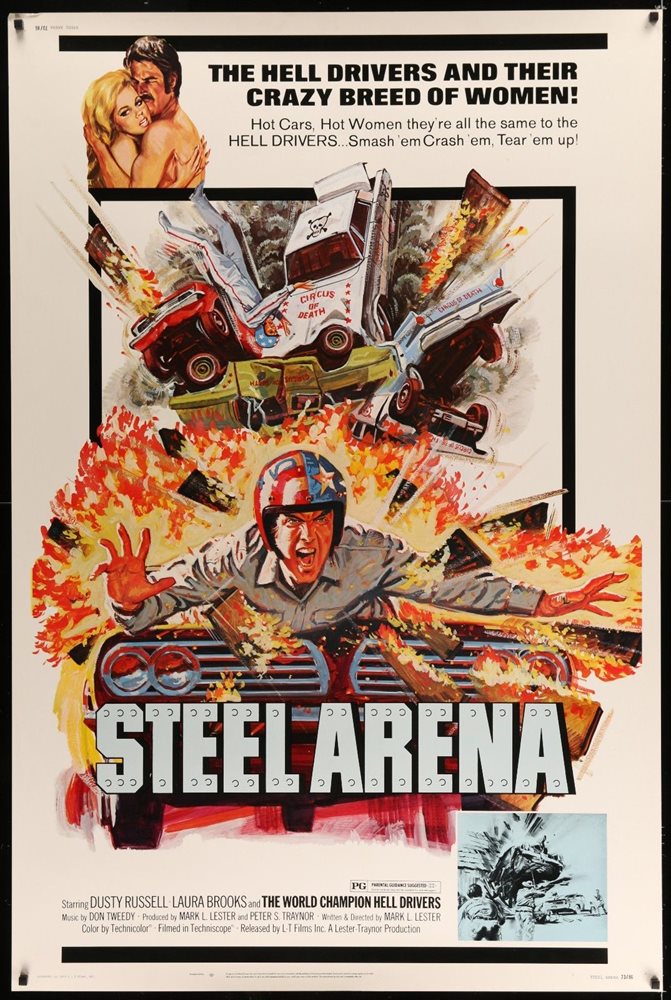

Steel Arena

Adler worked as a production assistant for Mark Lester in the making of Steel Arena (1973). He met Lester through Michaan, and Lester used 841 Gilman as a prep area for cars to be used in Steel Arena. Lester is known for making cult movies This was Lester’s first 35 mm theatrical feature. He writes about his experience making Steel Arena here.

Steel Arena tells the story a stunt driver and his quest to devise the ultimate stunt so that he can qualify to participate in a lucrative stunt show. Dusty Russell, whose real name is Bob Hanna, was a real-life daredevil and stuntman and played himself in the movie.

Adler found the stunt drivers and daredevils who worked on the movie to be funny and friendly men. He continued to work his way up the ladder in movie production management and led to production work on movies for the next 15 years as a production still photographer, boom operator, grip, assistant camera, and eventually production manager.

Adler Theatrical Agency

After Steel Arena, Adler started a theatrical agency. He was a location scout and an agent for actors and models and extras and crews. When called upon to provide marching bands, he did. Likewise animal acts, jugglers, fire-eaters, sword-swallowers, clowns, or elephants,

I imagine something like Broadway Danny Rose. I might be wrong.

Adler did only non-union films not Franchised by SAG, so he tended towards low-budget productions. A young Danny Glover was a client. Adler was a commission broker. He shut the agency down in about 1984. He returned to working as a commercial photographer.

The Tunnel Fire of 1991

The Tunnel Fire of 1991 was a large suburban wildland–urban interface conflagration on the hillsides of northern Oakland and southeastern Berkeley from October 19–23.

The fire killed 25 people and injured 150 others. The 1,520 acres destroyed included 2,843 single-family dwellings and 437 apartment and condominium units.

Adler was one of the first photographers on the scene and he shot hundreds of compelling photos. Through a friend who lived on Alvarado Road in the fire area he had an access pass into the fire area. As soon as the streets were cleared, he drove his friend’s van up there with a Roloflex and a tripod and light mater. He pretended he was Ansel Adams. Every shot was on a tripod and with a light meter. Before going up there he asked a curator at the Bancroft Library for advice. The advice – “Make sure to take notes of where you are standing and the orientation for each photo.” He did.

His photos were stunning. They were featured in “Firestorm,’91,” a one-man-show) in 1993 at the Berkeley Historical Society in the Veterans Building. That exhibit opened doors for Adler as a serious photojournalist.

The Whole World’s Watching

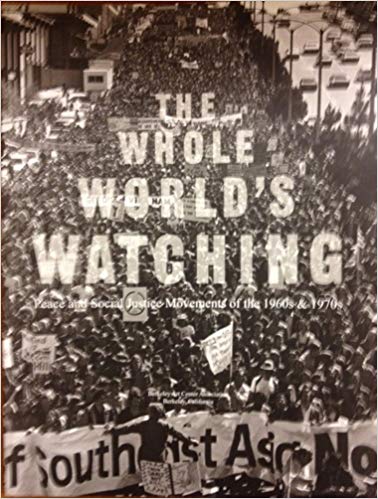

In 2001, Adler produced a photographic exhibit at the Berkeley Art Center and published The Whole World’s Watching, a collection of essays and photographs from the show.

Seeing the destructive impact of the firestorm made Adler that his negatives of the Sixties were much more important than he had thought. He conceived a project about the legacy of the Sixties. The title, “The whole world’s watching,” was a phrase chanted by demonstrators as they were beaten and arrested by police outside the Conrad Hilton Hotel in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Robin Legere Henderson was the curator at the Berkeley Art Center and was an accomplished grant proposal writer and known for putting projects together. Adler approached her with his vision. He brought the photographers on board, recruited the writers, and pulled the project together. It took five years to get funding, including from the California Council for the Humanities and National Endowment for the Arts.

P.S. Robin Legere Henderson has been featured in a Quirky Berkeley post

Stephen M. Silberstein made the book publication possible.

Of it, The Library Journal said: “Mario Savio, the late leader of the Free Speech Movement, notes in this celebration of San Francisco Bay activism that the region “‘s one of the few places…in the United States…where involvement in radical politics is not a form of social leprosy.’ This collection of photographs and short essays (mainly three to five pages long) relates many episodes of the protest movement that ignited in the Bay Area and spread throughout the country during the Sixties and Seventies. Contributors include highly regarded historians Leon Litwack (presenting an overview of the era) and Clayborne Carson (writing on the Civil Rights movement), as well as several award-winning photojournalists, who provide often stark examples of activists in action. The most intriguing stories are first-person accounts by participants, including Alice Hamburg discussing the Women’s Strike for Peace, Ruth Rosen remembering the early feminist movement, Donna Amador describing Latino Power, and HolLynn D’Lil recounting the 1977 protest of disabled citizens that led to the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.”

It is a beautiful and important book.

Nicaragua

In 2005 and 2012 Adler went to Nicaragua to photograph for Natasha Robinson. Her mission there is to introduce rural families to the use of coffee bean hulls for cooking fuel instead of wood. They were plentiful, free, and didn’t lead to deforestation; Biomass on a very retail level.

Adler’s photographs of Nicaraguan children are as compelling as any he has taken. They show joy on the one hand, extreme poverty on the other. He found the living conditions in rural Nicaragua to be brutally difficult.

In 2009, Adler took the space on Shattuck that he had used for his photography studio and storage for his light show equipment and started producing events, drawing on his past to produce events at the Art House. In the past, the space had been a welding shop and then April Watkins’ Art of Living with art and antique clothing.

Poetry Flash held its 40th anniversary celebration at the Art House. Poetry Flash is a literary magazine and website based in the San Francisco Bay Area; it publishes literary reviews, poetry, interviews, and essays as well as an extensive calendar of literary activities on the west coast of the United States

Adler has regular rock shows at the Art House. Many feature fabled musicians from the 1960s whose fame may have faded but whose musical chops have not. Posters from shows past line walls.

Dennis Loren makes the Art House posters.

He has been creating concert posters, album covers, CD packages and music-related graphics since 1967. His first three posters were done for Muddy Waters, The Youngbloods, and Jimi Hendrix – not bad. He has designed posters for The Fillmore, The Avalon Ballroom, The Great American Music Hall, The Warfield, and The Whisky A Go-Go among other venues.

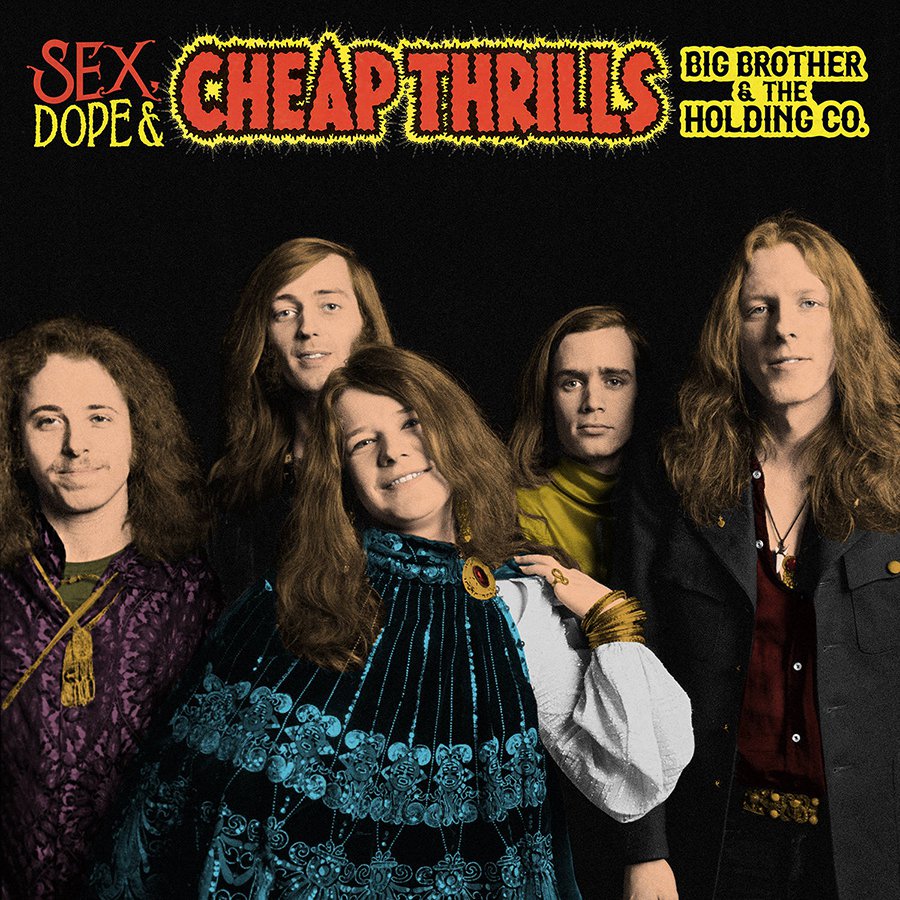

Before leaving the Art House, an update. I wrote in the Art House article that Natasha Robinson’s “San Francisco in the 60s” painting – with which I lead this article – was then slated to be used as the centerfold in Columbia/Legacy Recordings’ issue of a 50th anniversary set of Cheap Thrills in November, using its original title of Sex, Dope & Cheap Thrills.

It came to pass.

All these years gone by, Adler is also still in the photo and video business – weddings, bar mitzvahs, quinceañeras, family reunions, and portraits. You can see some of his work from these gigs here.

Adler has served as the curator for the Free Speech Cafe on campus.

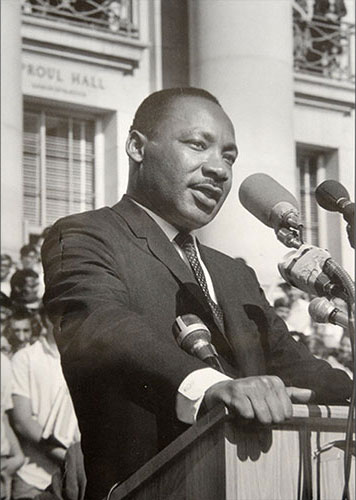

L to R: Gathered at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Student Union on Friday, May 17, 2002, Ronald Stevenson, Charles Henry, Helen Nestor and Harold Adler unveiled a photograph of Martin Luther King, Jr. speaking on Sproul Plaza. (Photo by Noah Berger)

He engineered the acquisition and mounting of an iconic photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. taken by Helen Nestor.

Dr. King spoke at Sproul Plaza on May 17,1967. He told the students ”You, in a real sense, have been the conscience of the academic community and our nation.”

Adler continues too to see his photography as a tool in the construction of social and economic justice. The photo above was taken in 2014 at the 45th anniversary celebration of People’s Park. For Adler, the struggle is still real.

Adler’s polymath career has come into focus after 50 years. With the Art House his hippie sand box/living room/living museum, he has found his last project. He may not have lost his ability to make like a chameleon and change colors, but the one Big Change he hopes for still involves the Art House.

With the Art House, Adler is a perfect ambassador from and for the Sixties. He acknowledges the excesses of the time and he believes that drugs killed the Sixties, but he is unabashed in his embrace of the music, the art, the ethos, the spirit, and the vibe.

Adler’s photographs may be found in Getty Images, at the California State Library in Sacramento, the Bancroft Library, the Moffit Media Center at Cal, and the Beat Museum in San Francisco. Ken Burns licensed an Adler photo for his Vietnam documentary television series.

The Berkeley City Council honored Adler by naming September 27, 2016 Harold Adler Day. That is an honor, but in my book it is not great enough. Harold Adler celebrates the culture of Berkeley in another era. He doesn’t live in the past, but he visits it and lets us step through the portal and visit it with him.

I took the draft post to my friend’s quarters. He was reading while drinking tea and nibbling on slices of oranges and Girl Scout cookies.

I asked what he was reading. He showed me.

I said, “I remember them. The orange biographies. I have strong memories of them at the Ludington Public Library in Bryn Mawr and the lower school library at Episcopal.”

He said, “Gabby just sent me a complete set. The Childhood of Famous Americans from Bobbs-Merrill. Part fact part fiction. Gabby’s working on complete sets of Augusta Stevenson’s Children’s Classics in Dramatic Form and the Landmark series. I don’t know what I’m gonna do with them. Read them then what?”

Not my problem. What does he think of the Adler biographical post?

You are getting good at this new road you are on, Tom. Thanks. M

It was great to see my old stomping grounds aka Berkeley where I had moved as a teen determined to be the poet I was with validation. Andy Clausen mentored me as only he would (we’re still friends) and when I moved to Mendocino County to continue writing ‘without all that noise’, I looked back at this polymath adventure with great affection remembering all my Telly adventures and people. Thank you for the beautiful photo history, memories, photographs, I was a bit younger than Mr. Adler but looked from a-far (ok, a few feet away) with awe and enjoyment. I thought he had hair like Dylan! Lived next door to Jane Scherr at one point and she took photographs of me and my small son for various Daily California articles. It was a wondrous time.