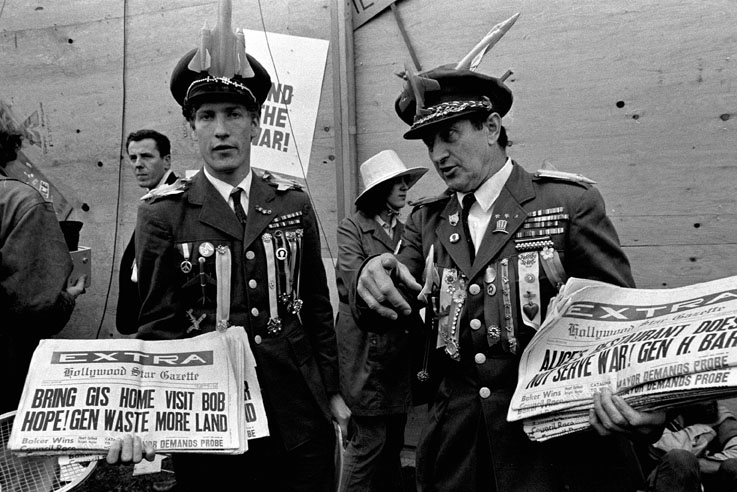

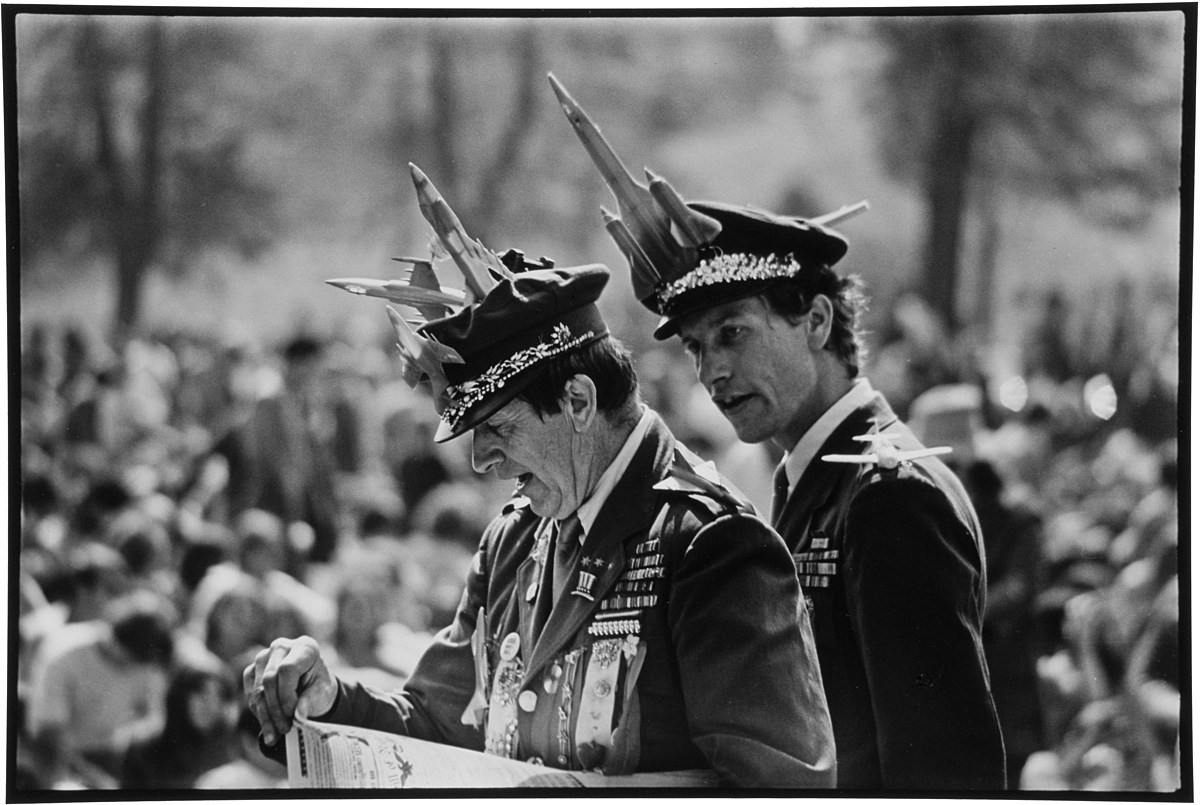

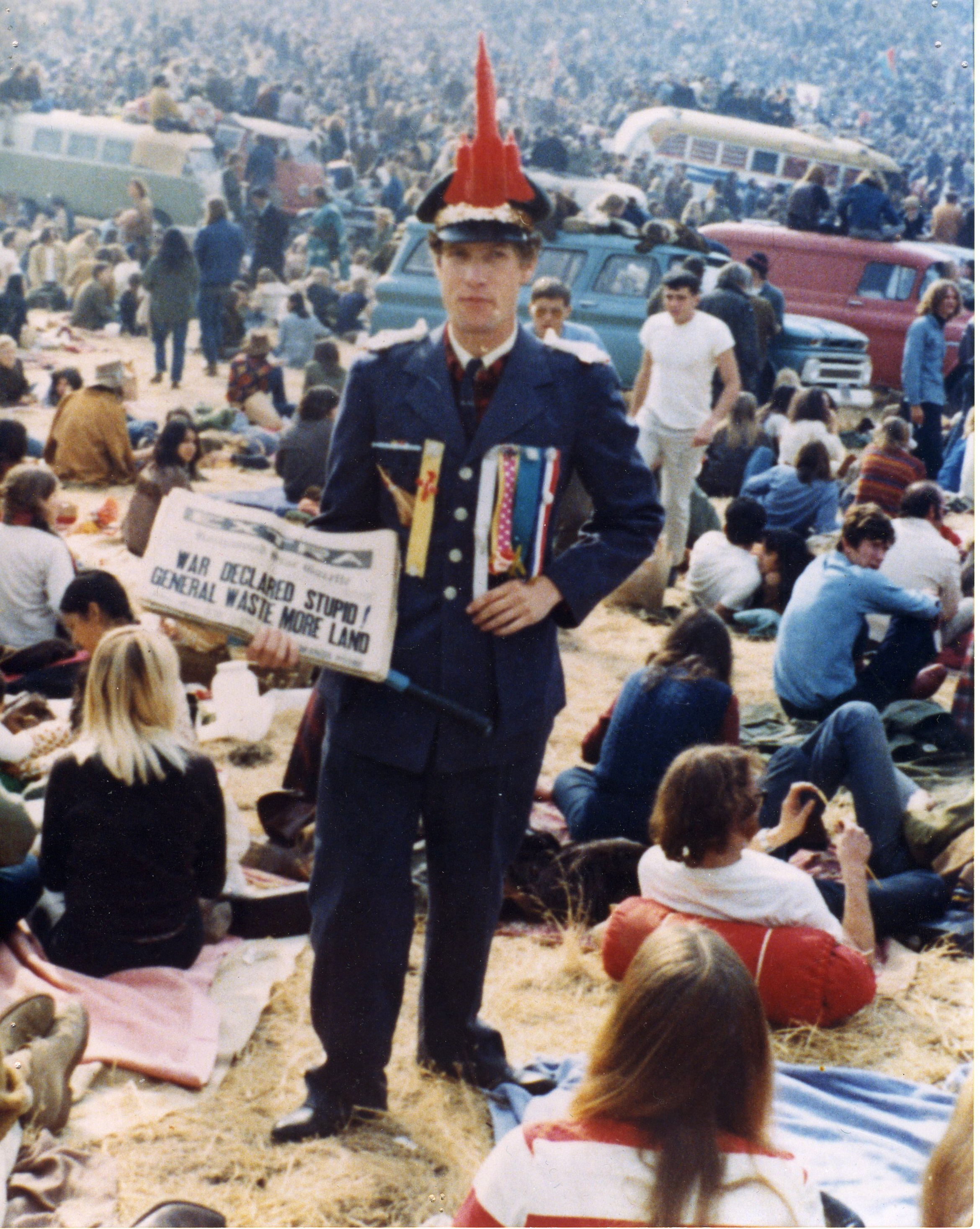

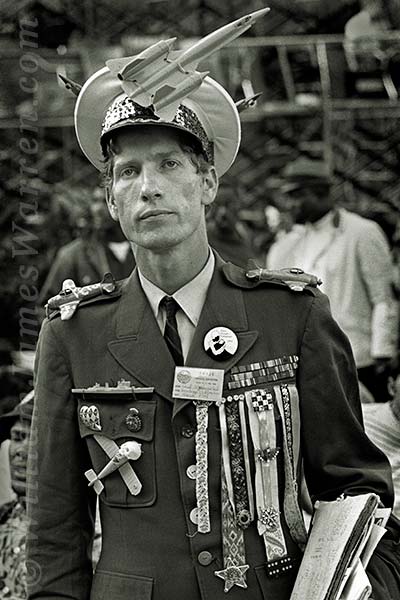

In 1969, a former Maryknoll seminarian from East Los Angeles named Tom Dunphy moved to Berkeley. Several years earlier he had been ordained “General Wastemoreland,” alluding to and mocking General William Westmoreland who commanded United States Army forces in South Vietnam. Dunphy in his Wastemoreland persona, bedecked in an over-the-top imitation of a military uniform, was a one-man anti-war guerrilla theater until the war in Vietnam ended, brightening and lightening Berkeley and anti-war protests around the country. He is still with us, doing good works as Tom Dunphy, with his Wastemoreland uniform safely archived at the Bancroft Library.

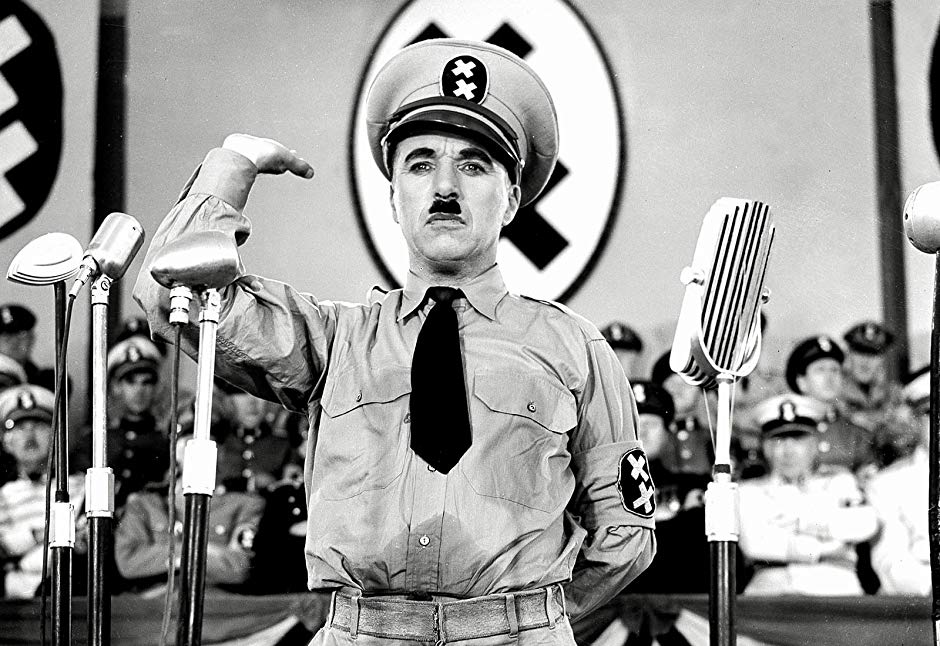

Satire is a powerful weapon against the powerful. For example:

I’m sure you can think of many other examples- The First Family by Vaughn Meader, The Great Society comic book, Barbara Garson’s MacBird, the string of presidential impersonations on Saturday Night Live beginning with Chevy Chase as President Ford and continuing to Alex Baldwin as President Trump, Tina Fey as Sarah Palin, and others. But if there are precedents for what Dunphy did – live in character and engage in one-man or two-man guerrilla theater aimed at stopping the war in Vietnam – they don’t come to mind.

Dunphy was born in 1944 into a devout German/Irish Catholic family living in the heart of Spanish-speaking Chicano East Los Angeles. His father worked as a bus driver for 50 years.

Roman Catholicism was an essential element of his family life. His mother Frances was drawn to the Jansenism theological movement of the 17th century. It emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination.

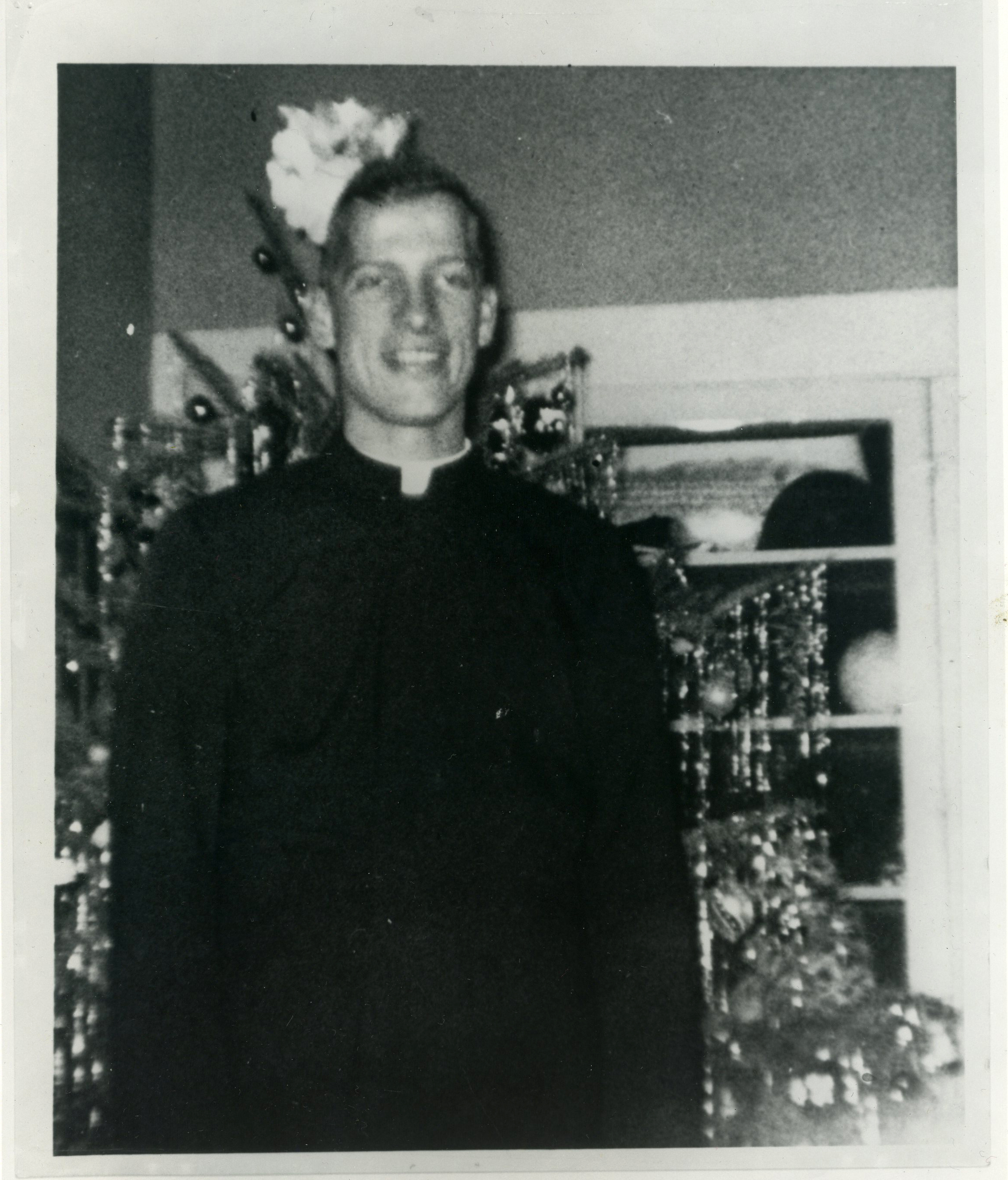

When a junior in high school, Dunphy entered the Maryknoll seminary in Mountain View, which provided four years of high school and four years of college education. Maryknoll is a missionary order. Its fathers and brothers are known for combating poverty, building communities, availing healthcare, and advancing peace and social justice. The Maryknoll order required two years of high school instruction, four years of college, and seven years in the seminary – 13 years to reach the final oath, ordination and mission-sending.

I asked Dunphy what about the priesthood appealed to him. He said, “I believed that God had called me.”

He spent years in Mouintain View, the Maryknoll seminary in Glen Ellyn south of Chicago, and then St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo. He earned several degrees. Most if not all of his classes were taught in Latin.

With still years to go before reaching full priesthood, Dunphy left the seminary, partly because he simply did not feel called to the priesthood any longer and partly because he disapproved of Los Angeles Cardinal James Francis Aloysius McIntyre’s rightwing politics. The Cardinal sent his priests to meetings of the John Birch Society to learn about communism and he recommended subscriptions to American Opinion and other Birch publications in his diocesan newspaper. Dunphy was squarely against fascism and the war in Vietnam. McIntyre was not. He had been exposed to liberation theology in the seminary, but was not yet a full-blown leftist. He just knew he didn’t like the war.

Dunphy spent a year at California State College at Los Angeles, now known as CSU Los Angeles. Although he was against the war in Vietnam, he was not attracted to the revolutionary rhetoric or propensity for violence that characterized a vocal component of the anti-war movement.

The Los Angeles Years

After the year at Cal State, Dunphy got a job as a social worker in South Central Los Angeles, then known as Watts. He was fired after perhaps a year as a result, he believed, of his growing anti-war activity.

In this period, Dunphy was attracted to the pacifism of the Hopi tribe.

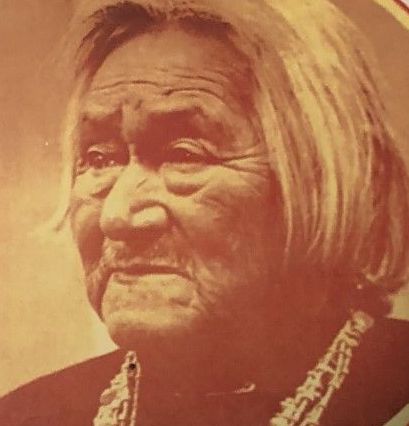

In 1967 he visited the Hopi Sovereign Nation in northeast Arizona. He provided draft counseling, advice on building Hopi independence, and did physical labor in the villages. He stayed in the home of Carol Tawangyawma, a Hopi princess with whom he would correspond for several decades.

Dunphy was inspired by the teachings of Dan Katchongva, Sun Clan leader from the village of Hotevilla. He is one of four Hopis who decided to or were chosen to reveal Hopi traditional wisdom and teachings, including the Hopi prophecies for the future, to the general public.

The Hopi told Dunphy he was protected by the Medicine Wheel or Sacred Hoop, which embodies the Four Directions, as well as Father Sky, Mother Earth, and Spirit Tree—all of which symbolize dimensions of health and the cycles of life.

Dunphy returned to Los Angeles. He was waiting to be sent on a mission.

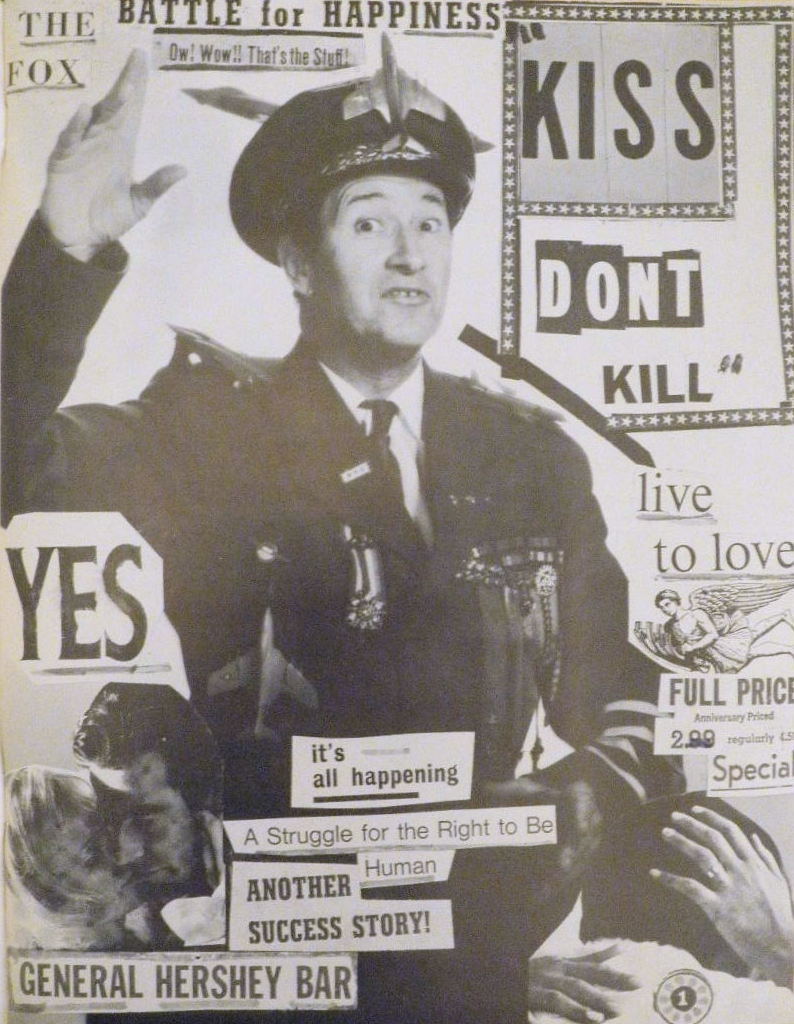

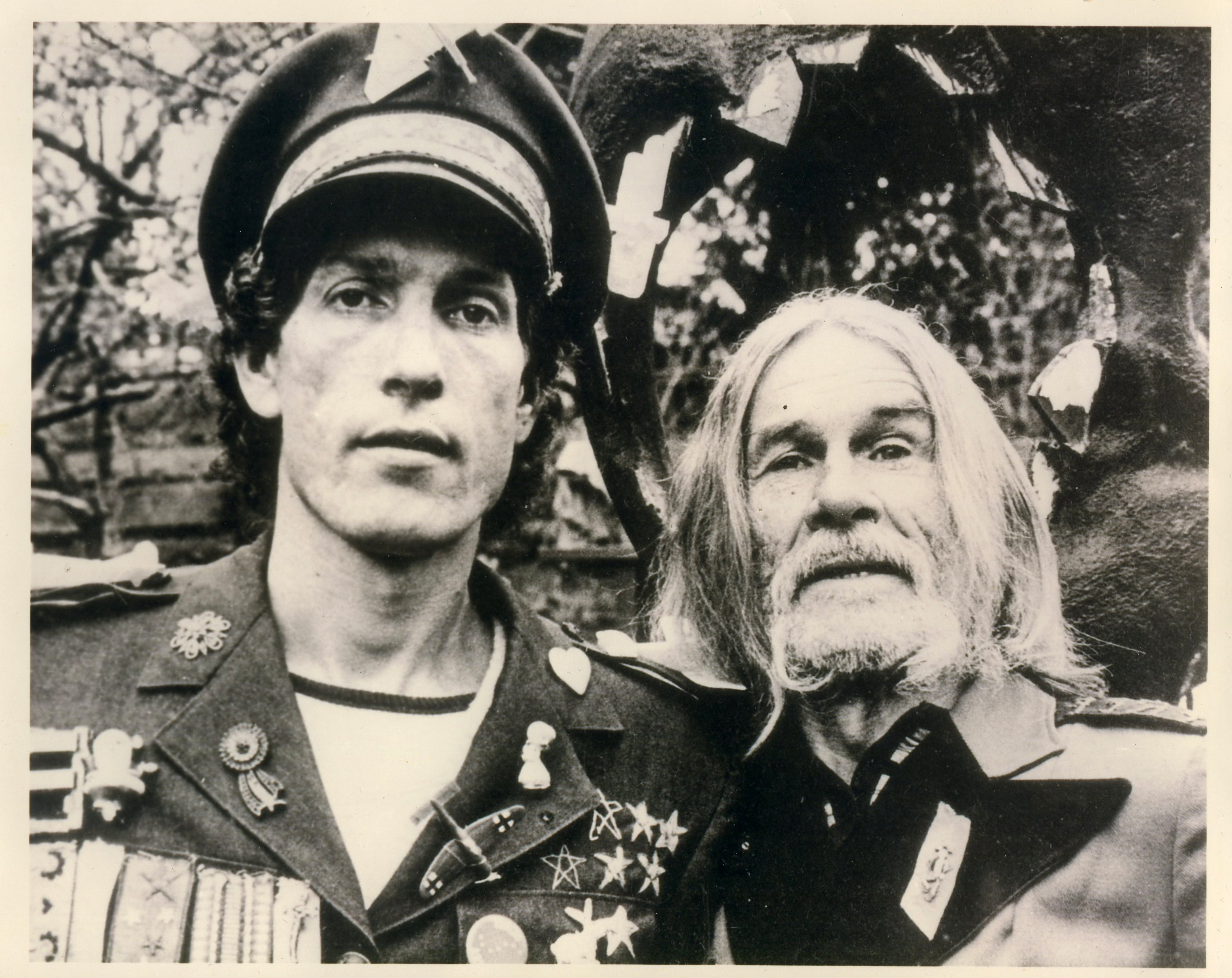

The mission appeared. Dunphy met General Hershey Bar, a former dancer named Bill Matons who after a few decades living as Calypso Joe and the Calypso Kid had adopted the satirical persona of a general who was a vehement opponent of the war in Vietnam. The nom de guerre was a play on General Lewis Blaine Hershey, the Director of the Selective Service System.

General Hershey Bar and General Wastemoreland were fellow travelers for about five years, but General Hershey Bar lived in Los Angeles and was never grounded in Berkeley. His story fascinates, and you can jump to another post if you want to know more.

The General had written a small satirical book entitled Kiss Don’t Kill. Dunphy was instantly struck with the same passion and conviction that had led him into the seminary. With General Hershey Bar, he felt as if he had been sent on an errand. For a year – more or less – Dunphy visited college campuses hawking Kiss Don’t Kill, sometimes in the company of General Hershey Bar and sometimes on his own.

The two traveled to an anti-war demonstration in San Francisco. Dunphy was still employed as a social worker and so had a car and gas money. As they left the demonstration for the trip back to Los Angeles, General Hershey Bar said, “Tom, would you like to be a general?”

Dunphy said “Yeah, okay.”

They settled on the name Wastemoreland (“I waste more land than any other general!”) and General Hershey Bar lined out the steps Dunphy had to take to become a general – make his uniform, adorn said uniform with medals and plastic war toys, print draft cards, and fake newspapers.at the Earl Hayes Press in Hollywood. The draft card said that the bearer of the card was “classified in Class 6-Z until PEACE DECLARED by General Hershey Bar…by President Doctor Spock…by President Richard Nixon.” There were Instructions on the back of the card on how to “burn or ‘boil’ your non-draft card and to surrender the ashes…please alter, forge, knowingly destroy, knowingly mutilate or in any manner change this illegal-slave-document.”

The two made hundreds of trips to college campuses, using satire (or is it parody?) to preach an anti-war message. Their jokes evoke, for me at least, a vaudeville comedian’s jokes. A few examples:

My partner General Hershey Bar is the sweetest general in the Pentagon. He’s the first general who said, “Kiss, don’t kill, you make more friends that way.”

Don’t get him mixed up,now. General Hershey Bar is the one with the plain chocolate. It’s the one in Washington D.C. that has all the nuts.

This is the longest medal ever given by Congress and it stood for, Long time, no peace.

General Hershey Bar liked to play tennis.

|

The two often carried tennis rackets as props, used with this joke:

War is a racket. If you’re going to have a racket, let it be tennis. Tennis anyone?

They also produced low-production-value comics called Peace NutsI.

The drawings were by William Stout, a young student on a scholarship at the Chouinard Art Institute within the California Institute of the Art.

Stout describes meeting the Generals and making the drawings for Peace Nuts:

I was attending my first semester as an illustration major at the Chouinard Art Institute (aka California Institute of the arts — CalArts). The school was very accessible to the public. Anyone could walk into the school patio, the school’s main gathering place. One day in the summer of 1967 these two street characters, General Hershey Bar and General Waste More Land (Calypso Joe and Tom Dunphy), wandered onto campus. They asked around if anyone knew of any comic book artists at the school. Some of my fellow students pointed over to me, as I had already established myself as the number one comics fan within the school.

They approached me and pitched me on doing a political comic book featuring them. It sounded like fun, so I agreed. I drew the book on spec; the resulting profits from book sales would be split three ways. I was given only one weekend to draw the entire book, which is why it looks so damn crude. The Generals wrote the text; I drew the images. They asked for it to be drawn in the deceptively simple style of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. I added the little butterfly character and his comments to each panel, which the Generals loved.

They gave me a small stack of Those Lovable Peace-Nuts after it was printed. Several of the cartoons from the book ran in the L. A. Free Press, which in theory helped to promote the book.

My father was furious with me for drawing the book. He worked in the aerospace industry and feared I would be labeled an anti-war communist and that he would lose his government security privileges. As a result, it became the first time I began to question our country’s so-called freedom of the press. Years later I lived behind the Iron Curtain while making the Conan the Barbarian movie and discovered that Yugoslavia had much greater freedom of the press than we had in America.

I never made a penny of royalties. When asked, the Generals explained: ” Hippies don’t have any money — so we’re giving the books away for free.” Well, I did indeed receive my third, as a third of nothing is nothing. I eventually made a small bit of dough years later; the comics became somewhat valuable as they were rare and one of the first underground comix ever published (I think our book even came out before Robert Crumb’s first issue of Zap Comix). I still have a few that I sell for $250 each.

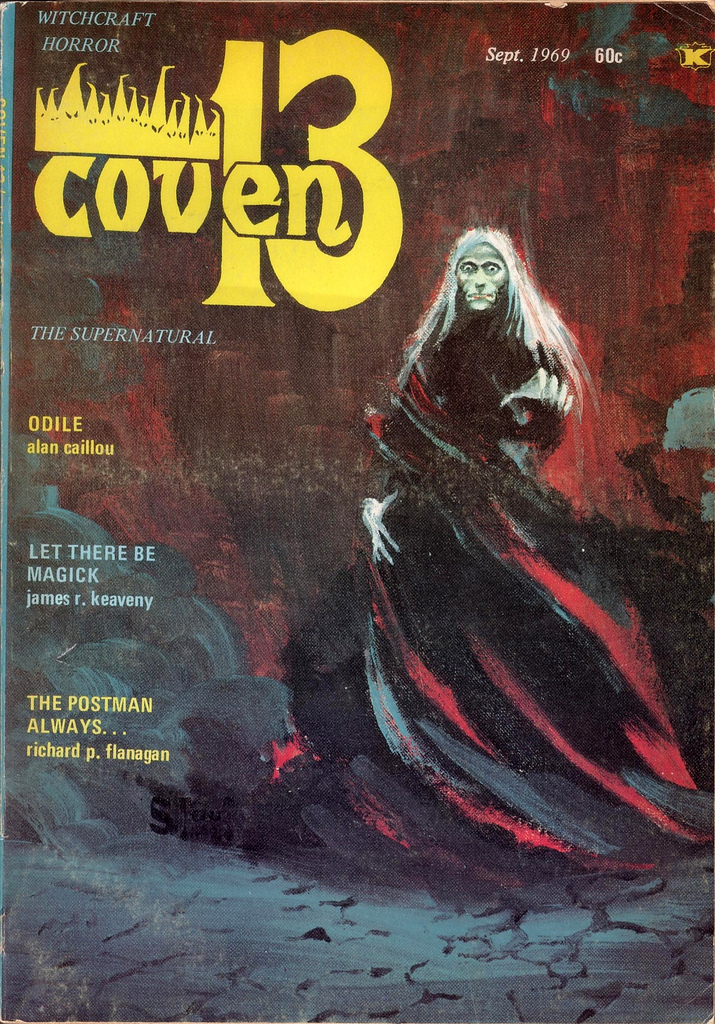

According to Stout’s website, he began his professional career in 1968 with the cover for the first issue of the pulp magazine Coven 13. By deduction, Peace Nuts was pre-professional career. He has gone on to become a famously diverse artist of international renown. In late November he saw publication of Fantastic Worlds – The Art of William Stout, a massive retrospective on his fifty-year career as an illustrator, comic artist and film maker.

Early in his career as General Westmoreland, Dunphy appeared with General Hershey Bar on the Joe Pyne television show. Pyne was a pioneer of the confrontational interview, a master of insult and vitriol. He was a conservative, but a conservative who opposed racial discrimination and supported labor unions.

Pyne started each show leaning into the microphone: “My name is Joe Pyne, and the action starts right here.” Pyne was pro-Vietnam War, and he made a frontal attack on Wastemoreland’s Catholicism – “How do you reconcile the fact that you don’t support the war but the National Conference of Catholic Bishops does?”

This was not a tough one for Wastemoreland. “I really believe what they taught me in seminary, that Jesus Christ was the Prince of Peace.” Here he referred to Isaiah 9: 6-7: “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace.” Like the constants on Family Feud shout as they clap for their opponents – “GOOD ANSWER!”

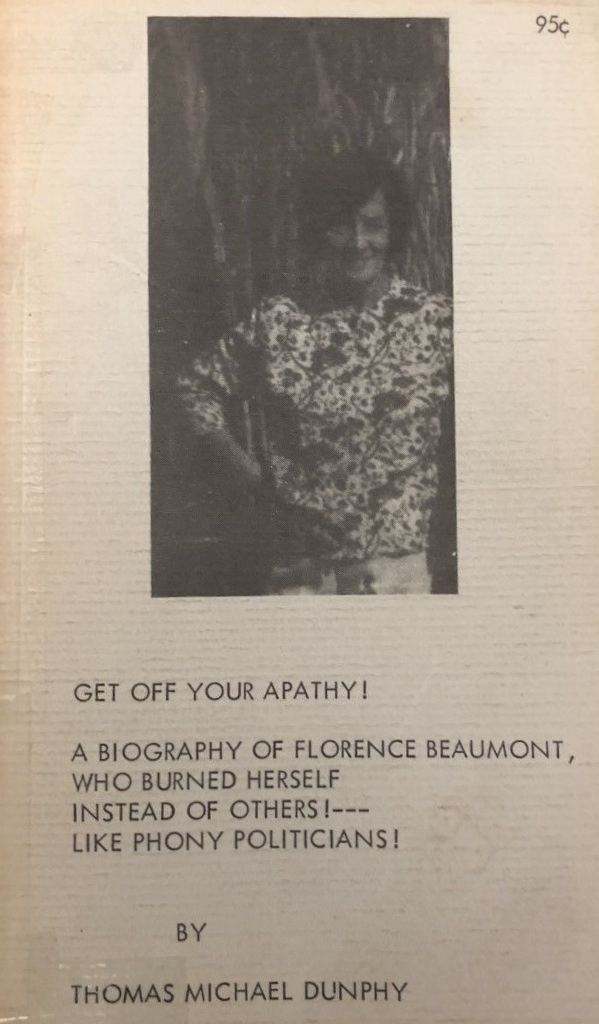

For his last several years living in Los Angeles, Dunphy slept on the couch of friends and wrote Get Off Your Apathy! about Florence Beaumont, which was published by General Hershey Bar’s Handicap Publications.

On October 15, 1967 Florence Beaumont, a Southern California housewife and mother, became so frustrated with the lack of progress toward ending the war in Vietnam she went to downtown Los Angeles, set her purse down in front of the Federal Building, poured gasoline on herself, and set herself on fire. She is said to have walked about 40 feet before collapsing.

Joan Baez wrote a poem about Florence, dated November 20, 1967. It is included in Get Off Your Apathy.

For these years, Dunphy ate one meal a day, borrowing from a discipline that he had learned in the seminary. He wrote poetry and read it in what was left of the Beat scene coffee houses.

When it came to Dunphy’s real-life interactions with the military, specifically his experiences with the Selective Service System and its mission of rapidly providing personnel for the military in a fair and equitable manner, the theater didn’t stop.

He initially sought classification as a conscientious objector because he was opposed to serving in the armed forces and bearing arms on the grounds of moral and religious principles. He was required to appear before his local board to explain his beliefs, which he did – dressed as General Wastemoreland. At this point, he had in the persona of General Wastemoreland made dozens of antiwar appearances with Genereal Hershey Bar, had written Peace Nuts, and had appeared on the Joe Pyne show. Yet, amazingly, he couldn’t find a single priest in Los Angeles to confirm his opposition to serving in the armed forces on religious principles. The Draft Board did not accept his claim for CO status.

Dunphy did not relent. He created the First Holiness Church for the Liberation of Love and Peace.

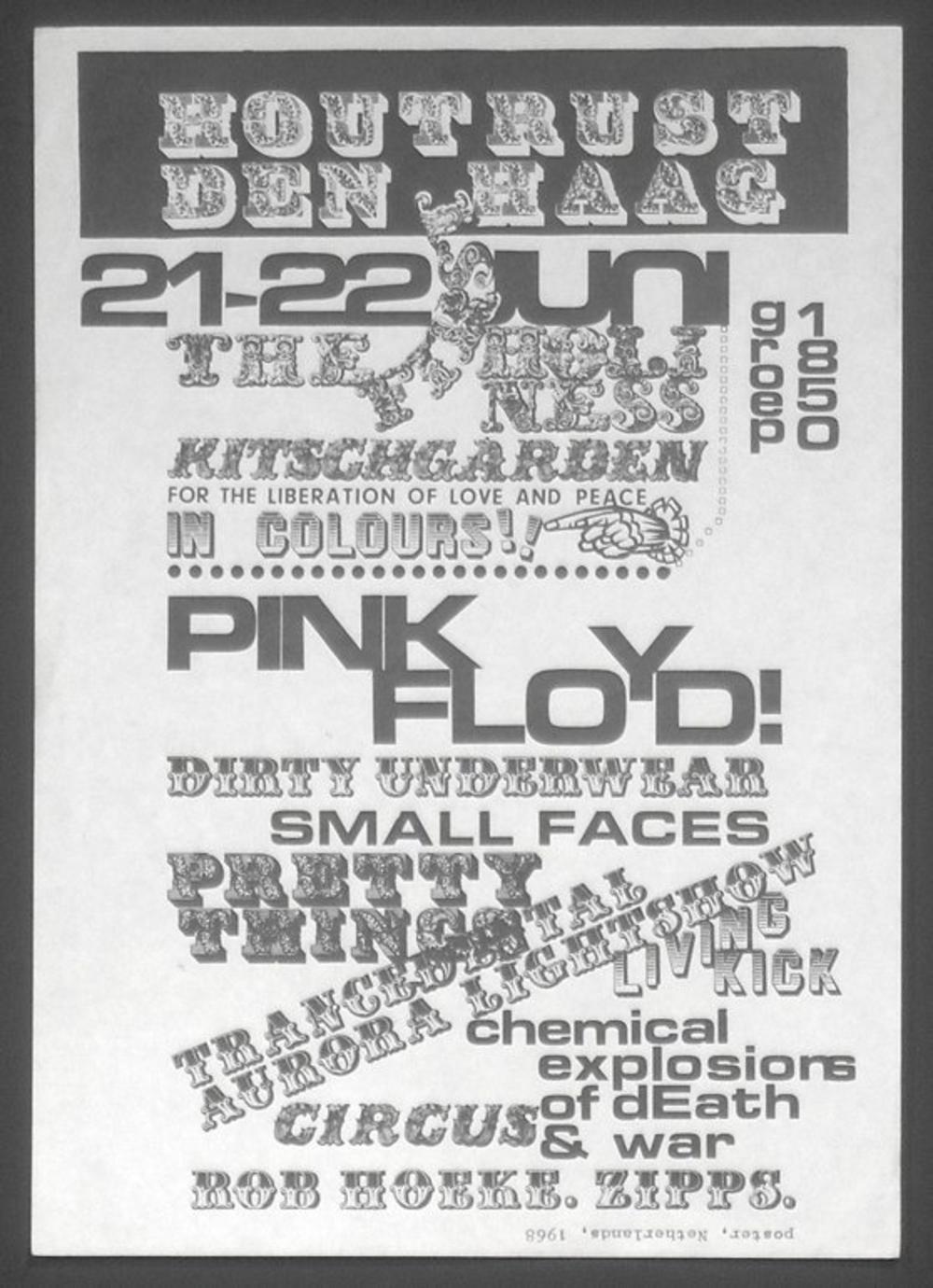

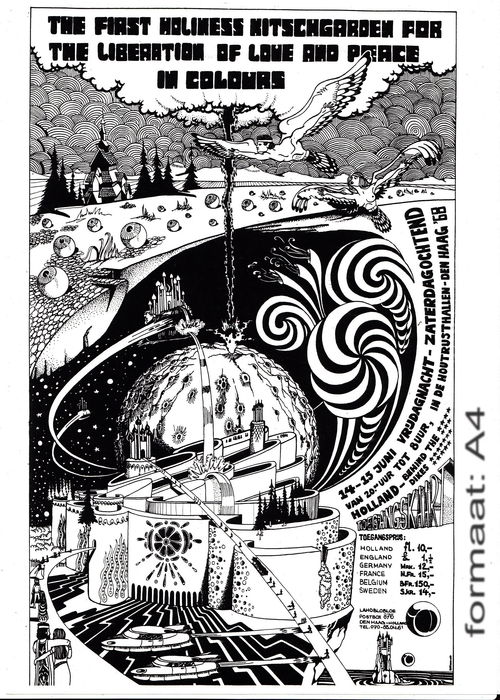

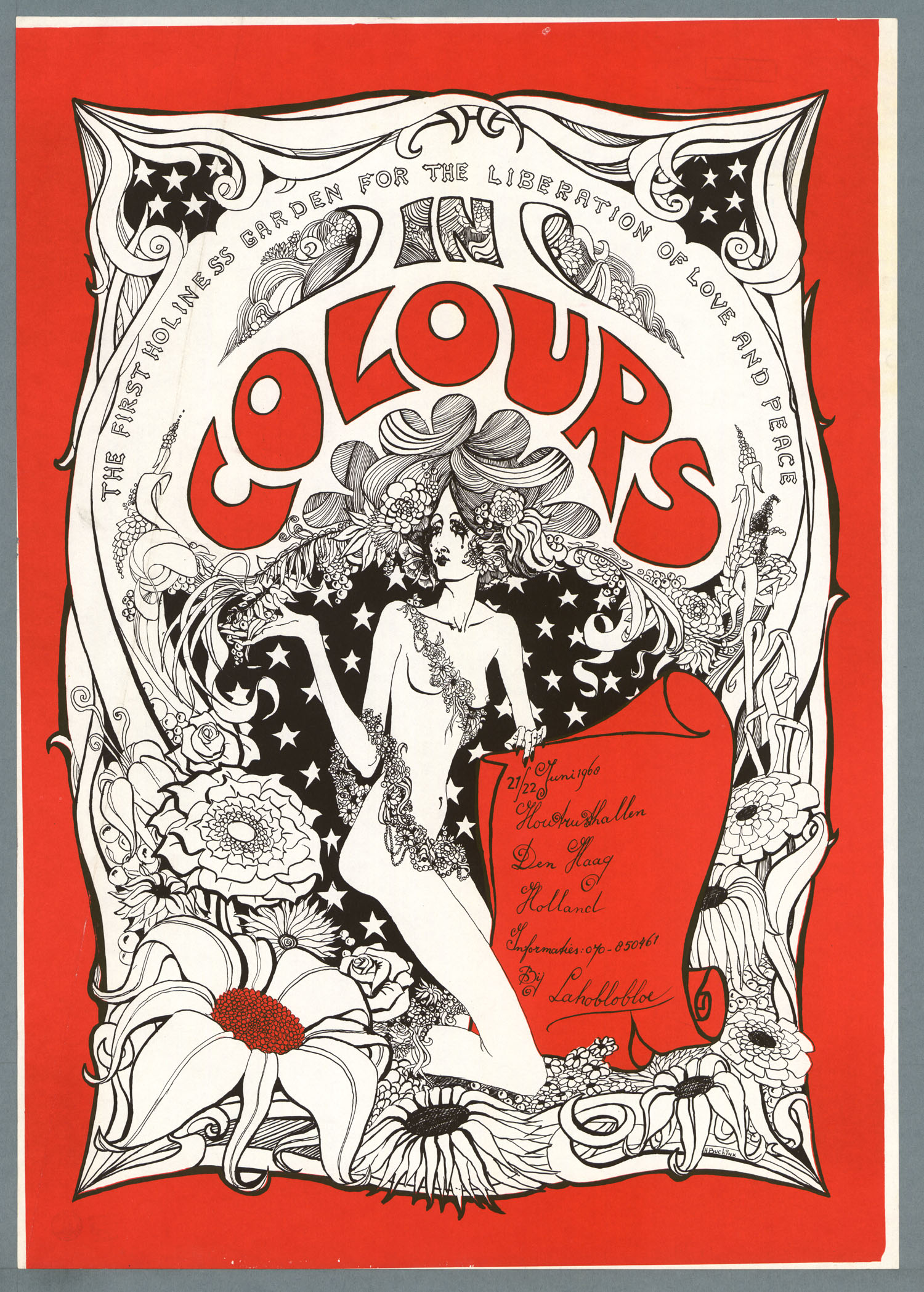

I wonder if in so naming his church Dunphy was aware of the concert entitled The First Holiness Kitschgarden for the Liberation of Love and Peace in Colours held in The Hague, The Netherlands, on June 21-22, 1968. Performers included Pink Floyd, The Cream, Small Faces, Moody Blues, Traffic, and more. There are at least four other versions of this poster. I applaud my self-restraint in not showing them.

Dunphy appointed himself Pope of the new church and, dressed as a Pope should dress, he returned to the Draft Board. He chanted in Latin, he told other men showing up for induction not to be sheep, and he threatened those taking part in the induction with a Hamburger Trial, not unlike the Nuremburg trials, because they had made hamburger meat of so many young men. He was deferred.

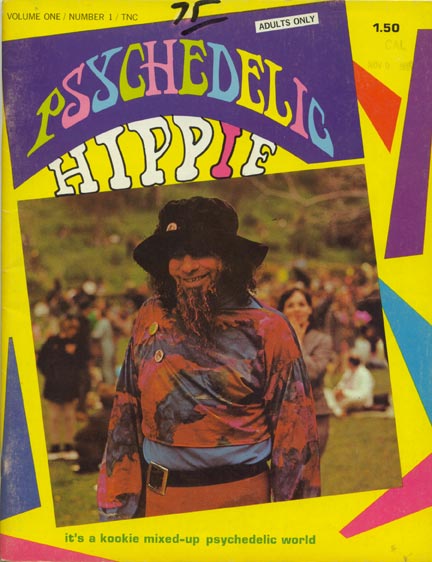

Although he lived in Los Angeles, Wastemoreland loved the counterculture scene in San Francisco.

This is a short clip from the 1998 movie Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Johnny Depp as Hunter S.Thompson recalls the riding the high-water mark of the crest of the counterculture wave in San Francisco with free concerts in the Panhandle of Golden Gate Park.

At 1:27-1:29 of this clip we see Wastemoreland getting his groove on in the Panhandle. The clip shows the Jefferson Airplane playing while the soundtrack is the Youngbloods.

In 1968, Wastemoreland and Hershey Bar came to the Bay Area for an anti-war demonstration at San Francisco State. Check out this iteration of the uniform – a toy submarine is attached above the right breast pocket.

Semanticist S.I. Hakkawa was President of SF State. He sought to strike a reasonable balance in the demonstrations, suggesting that he debate the antiwar elders. He made his opening speech in support of the war. As an anti-war leader took the stage, Hayakawa pulled the plug on the microphone. We perhaps remember him as “Sleeping Sam” in the United States Senate. He would be remembered less often but more fondly had he not run for and served in the Senate.

The Berkeley Years

Dunphy moved to Berkeley for good in 1969. Several years of couch-surfing In Los Angeles while writing Get Off Your Apathy had left him penniless. He relied on the kindness of his sisters Ginger and Rose but lived much of the year on the street.

By the end of the year he had addressed some mental health issues and had pulled out of the dive. He made a new uniform, something which he did several times over the years, starting with a uniform from an Army surplus store and then embellishing it. With a new uniform he once again emerged as General Wastemoreland in public.

He was part of the free-concert free-food free-everything scene at Provo Park. After several young men burned their draft cards, Wastemoreland wss quoted in the Barb as saying he was against burning draft cards, but advocated boiling them. Humor!

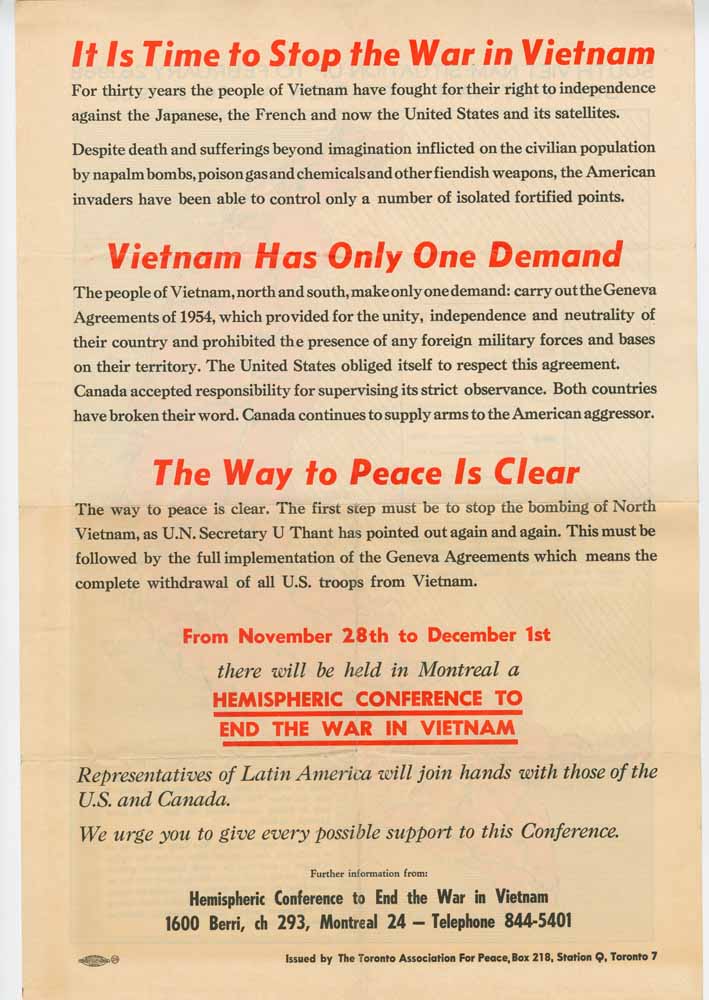

In late November, he flew to Montreal for the Hemispheric Conference to End the War in Vietnam as General Wastemoreland. The leaders of the U.S.Delegation were Michael Myerson (Director of the TriContinental Information Center, and former International Secretary of the W.E.B. DuBois Clubs of America), .Dagmar Wilson (founder of Women Strike for Peace), and actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee. It was a Very Serious Old Left delegation and conference, not a natural fit for his modus operandi of spontaneous, surprise performances in public spaces to an unsuspecting audience, drawing attention to the war in Vietnam through satire, protest, and carnival techniques.

Hoàng Minh Giám was the leader of the North Vietnamese delegation. It was Giám who gave Dunphy the microphone and let Dunphy tell anti-war jokes in French Vive le General!

Giám then presented Wastemoreland with a medal, quipping “You are my favorite general.”

Wastemoreland quipped right back – “Even over General Giáp?” He referred here to General Võ Nguyên Giáp of the Vietnam People’s Army, considered one of the greatest military strategists of the 20th century

Giám ending the quipping -” Even over General Giáp.”

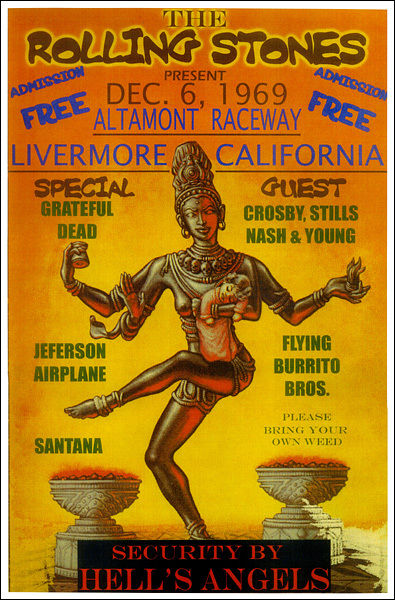

From Montreal, General Wastemoreland advanced to the Altamont Speedway (also known as the Altamont Raceway, Altamont Motorsports Park, Altamont Raceway Park and Arena, and Bernal Memorial Raceway) in the Altamont Pass (formerly Livermore Pass), a low mountain pass in the Diablo Range of Northern California between Livermore in the Livermore Valley and Tracy in the San Joaquin Valley.

He didn’t come for the races. On December 6, 1969, General Wastemoreland attended the Altamont Speedway Free Festival in the Altamont Pass. His sister Ginger’s ex-boyfriend gave him a ticket. The concert was originally scheduled for San Jose, then the Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, then the Sears Point Raceway south of Sonoma, and at the last minute at Altamont.

General Wastemoreland worked the crowd with his anti-war, anti-military gospel, but even he couldn’t keep the peace in Altamont. What was supposed to be a west coast version of Woodstock descended into dystopian violence at the hands of the Hells Angeles who had been tasked with security.

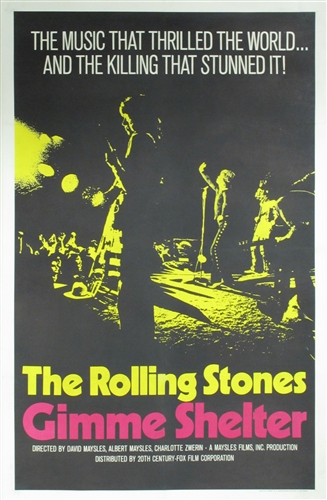

Filmmakers Albert and David Maysles shot footage of the event and incorporated it into the 1970 documentary film titled Gimme Shelter. Wastemoreland appears briefly in several sequences of the movie, which led his mentor General Hershey Bar to sue him.

When Hershey Bar disowned Wastemoreland, he briefly teamed up with Joe Covelo, who assumed the persona dramatic of General Dismay, after Air Force General Curtis LeMay. Dismay didn’t last long, and Hershey Bar moved on to another gig.

Anyways – Altamont. was a bummer. For some it marked the spiritual end of the Sixties.

John Lennon declared 1970 to be Year One for Peace. For General Wastemoreland, it was a big year.

In January, he was arrested in San Francisco for wearing a military uniform illegally and blocking a sidewalk. The February 6th edition of the Los Angeles Free Press reported:

General Waste-More-Land was cut loose from charges of wearing a military uniform illegally and blocking a sidewalk Jan. 20 and 21 “in the interests of justice,” according to General Hershey Bar.

Judge Gerald O’Hara of San Francisco Municipal Court ruled that military uniforms were under Federal jurisdiction and local authorities couldn’t use this excuse to hassle the anti-war General.

Judge Harry Low decided the following day that one man – not even a man o General Waste-More-Land’s stature – couldn’t possibly block a sidewalk single handedly. General Curtis Dismay noted that young men everywhere should take advantage of this tremendous victory and wear their uniforms for peace.

The General reported that the FBI had returned his uniform to him, but that they had treated it disrespectfully and broken some of the plastic airplanes.

On March 7, 1970, three days after his 26th birthday, he married Elizabeth Schwartz at the University Lutheran Chapel, 2425 College Ave in Berkeley. They met in front of the Med. She was a Hare Krishna. They were living together in her home at 2728 Garber.

The wedding was announced in the February 27 edition of the Barb. “All the local antiwar people” were cordially invited.

Harold Adler, a professional photographer, made these great photographs of the wedding. He did so in his capacity as a friend and admirer, not as a professional gig.

Their home on Garber is in the background, the two-story house. Wastemoreland carries a drawing of the Yellow Submarine.

Two of the officiants are shown in this photo, Richard York of the Berkeley Free Church (frizzy hair), and Bishop Phillip Emmons Isaac Bonewits of the Universal Life Church. Also officiating were the Rev. Mike Likin of the Episcopal Church Berkeley, his Holiness Pope Morris Kight of the Holiness Church for the liberation of Love and Peace, and a priest from the Russian Orthodox church.

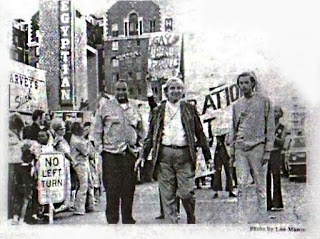

Kight (center) at the first Gay Pride Parade, Hollywood Boulevard, in 1970 (Photo: Los Angeles Free Press)

Kight, whom Dunphy knew in Los Angeles, was a gay rights pioneer and peace activist. He is considered one of the original founders of the gay and lesbian civil rights movement in the United States.

Bonewits became an American Druid who published a number of books on the subject of Neopaganism and magic. He was also a public speaker, liturgist, singer and songwriter, and founded the Druidic organization Árn Draíocht Féin, Dunphy’s sister Rosa stands to his left in the photo below. General Hershey Bar stands behind the couple holding a chicken piñata.

Standing to our right of General Wastemoreland is Mona Bazaar, the author of several self-published books: Exotic Recipes for a World Without War (1963); Free Huey: Or the Sky’s the Limit (1968); The Trial of Huey Newton; Selected Articles and Statements (1968); Black Fury: Police Brutality, White Racism (1968); The End of Silence (editor) (1970); and Cookbook in Solidarity with the Symbionese Liberation Army (date unknown).

Standing next to Schwartz is the officiant from the Russian Orthodox Church.

Instead of a five-layer cake, the General had a five-letter cake, spelling “peace.”

The Barb reported on the wedding in the March 13, 1970 issue, page 5:

Within the report: “But things didn’t go off without a hitch at the hitching time – Wastemorland and best man General Hershey Bar spent too much time on the Avenue looking for confetti poppers for the 21-gun salute, and showed up half an hour late. 150 guests were waiting including many celebrities among the street people.”

Things were still good between Dunphy/Wastemoreland and Matson/Hershey Bar. It would not be long before General Hershey Bar would be alleging that Dunphy was in reality a CIA domestic spy .

The marriage didn’t last long. As Dunphy stood looking out the window of their house the day after the wedding, Schwartz made it clear that the marriage was not going to work. Dunphy stuck to his pacifist core and simply left.

Later in 1970, Dunphy as Wastemoreland was flown to England and spent several months in Europe.

Warner Brothers spent nearly a million dollars putting together the Medicine Ball Caravan, as 150 recruited hippies undertook a cross-country tour from San Francisco to D.C., living the “Aquarian lifestyle” and staging a series of free concerts along the way. It was not without authenticity, as Wavy Gravy and some Hog Farmers were part of the group. Wavy remembers the performances by B.B. King as the highlight of the caravan. Tom Forcade, founder of High Times magazine, launched a demonstration against the making of the film.

A 15-man French film crew recorded the series of free concerts staged during the American leg of the tour.. Artists would fly in and perform. It was meant to be a sequel to Woodstock. François Reichenbach, the original director, was replaced during the editing by a cocaine-fueled group of editors who were responsible for the not-specifically-great finished product.

A group of rich Berkeley hippies somehow connected to the caravan paid for Dunphy/Wastemoreland to fly to Washington D.C.

In Washington he met up with the caravan,appeared in an anti-war demonstration, and made the trip to London.

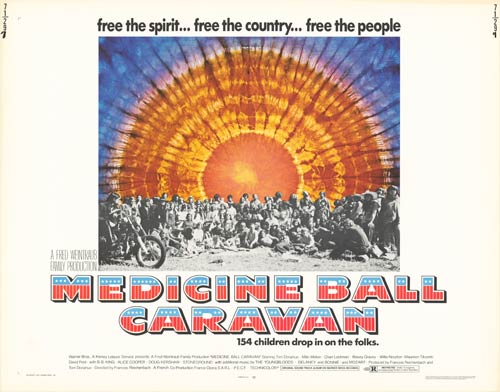

The crowning moment of the time in England was to have been the last concert of the Medicine Ball Caravan. The concert was held on August 31st at Charlton Park, Bishopsbourne, Kent near Cantebury. It was an utterly profound failure.

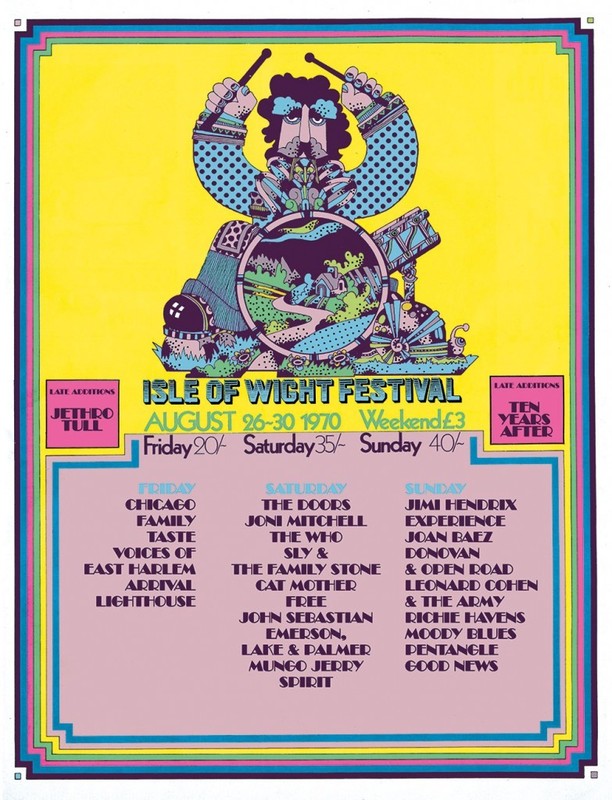

Reality met artifice, as the Isle of Wight concert was scheduled the same weekend. It had booked Jimi Hendrix Chicago, The Doors,The Moody Blues, The Who, Miles Davis, Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Jethro Tull, Sly and the Family Stone, Ten Years After, and Emerson, Cantebury was sparsely attended – perhaps 1,500 people. When the movie was released to theaters in August of 1971, the youths who were supposed to flock to the theaters stayed away in record numbers and Rolling Stone named it one of the ten worst films of the year

After the Cantebury Festival, Dunphy stayed on in London for several months as the guest of Jay and Fran Landesman.

They were a high-profile hip American couple in London, with counterculture connections stretching from the Beats to the beautiful people of the late 1960s.

To make his little bit of money last, Wastemoreland reverted to his routine of one meal a day. He managed to meet George Harrison and asked that the Beatles say something about Generals Hershey Bar and Wastemoreland. George said that he’d take it up with Apple Records.

At the Landesmans he met Niccolò Tucci, an Italian writer who before World War II, had worked for Mussolini’s propaganda ministry. He traveled to New York as a fascist propagandist in 1937 but soon became disillusioned with Fascism and devoted himself to anti-Fascist propaganda.

Tucci didn’t laugh when he saw Wastemoreland’s uniform. Wastemoreland asked him why he hadn’t laughed. Tucci said “That uniform is the most anti-fascist uniform I’ve ever seen.”

Dunphy/Wastemoreland finished the year appearing on the David Frost show in London. It was a fine hour for Wastemoreland but for Frost, not so much.

On November 8, 1970, David Frost booked Jerry Rubin as a guest on his television show. You may watch part of the show here. Berkeley’s Stew Albert was on stage with Rubin at the beginning of the segment By the end of the segment, some 20 Yippies – including General Wastemoreland – had taken over the stage in front of 17,000,000 viewers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WxjnfDToQmA

On almost any possible level this clip is worth watching. The other main guest was anthropologist Robert Ardrey who compared the behaviour of his fellow guests with that of young chimpanzees! David Frost saw the show as an advertisement for law and order. Others saw it differently. General Wastemoreland eloquently explained that his uniform was a tribute to the millions who died in world wars.

Before leaving Europe, Wastmoreland went to Rome to meet Fellini – Tucci had set it up. Wastemoreland lived hand to mouth crashing with students for a few days, calling Fellini’s office until he was given a five-minute audience.

He went in full Wastemoreland anti-military splendor. Fellini had maybe 50 people in his office, all anxious to meet this offbeat American Wastemoreland. Fellini repeated “General Waste-More-Land” several times, emphasizing each syllable, laughing out loud each time. Fellini asked Wastemoreland what he could do for him.

Wastemoreland: “Nothing, I just wanted to meet you. Niccolo Tucci told me I should meet you.”

Wastemoreland told Fellini that the year before he had gone to see Fellini’s Satyricon at the Fine Arts Cinema/Northside Theater on Euclid in North Berkeley with his sister. Wastemoreland grasped the satire immediately and laughed loudly soon after the movie stared. Patrons hushed him and threw popcorn. And then they got it and started to laugh.

Fellini told Wastemoreland he’d like to see him again, but Wastemoreland had to hitch to Germany to fly back to the United States. Felalini handed Wastemoreland a banknote and told him to go buy some cigarettes for his trip to Germany. He asked Wastemoreland if he’d like to meet Felini’s mother, Ida Barbiani. Wastemoreland did, and got a kiss on each cheek. She understood his uniform.

Anna Magnani, an actress in Fellini’s circle, walked Wastemoreland down a flight of marble stairs to an inner courtyard that led to the street. She looked at the banknote and told him that it was worth about $40. Wastemoreland bought a pack of∂ cigarettes and a train ticket to Germany.

In Germany, he met his grandfather’s brother. Wastemoreland was the only member of his family in the United States to learn German. He found his grandfather’s brother and his family to harbor favorable feelings for Hitler. He came to understand why his grandfather had no contact with them.

Back in the USA, Wastemoreland kept up his one-man guerrilla theater. He went from state to state, campus to campus, living on the generosity of students. He believes that he was arrested 52 times.

The bottom photo was taken in April, 1972, during demonstrations against President Nixon’s ordering the renewal of bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong and the mining of Haiphong Harbor. He stands on the steps of the Federal Building on Golden Gate Avenue, San Francisco.

Later that day, Wastemoreland was standing on the corner of Telegraph and Durant as street battles heated up. As demonstrators smashed the windows of the Bank of America, police grabbed the General, who had done nothing more than watch. They sent him to Napa State Hospital where he was forcibly injected with Proloxin, a long-acting form of fluphenazine and is used to treat schizophrenia.

More or less in 1976 Wastemoreland moved to Cotati.

His sister Ginger lived in Cotati and urged him to move there. She was a model, shown in these two sculptures.

Cotati had a major counterculture scene going in the sixties. It embraced Wastemoreland.

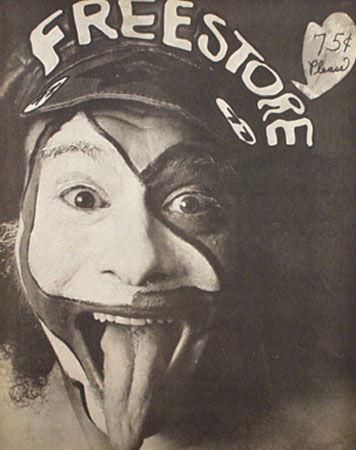

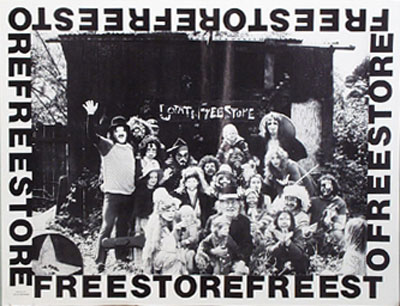

Wastemoreland is shown in this photo with Vito Paulekas in Cotati. Wastemoreland had known Vito in Hollywood. Vito was the son of Lithuanian immigrants. Via time in a reformatory, working as a marathon dancer, time in prison for armed robbery, and a stint in the Merchant Marines, he re-invented himself with an art studio and a clothing boutique featuring early hippie fashions. He was part of the Los Angeles “freak scene” and influenced musicians as diverse as The Byrds and Frank Zappa.

In Cotati, Vito and his LA friend Carl “Captain Fuck” Franzoni opened the Free Store street theatre and performance group.

The Free Store was a large shed from which many Cotati citizens outfitted themselves without charge from cast-off clothes, shoes and accessories that were left there.

The Free Store was a large shed from which many Cotati citizens outfitted themselves without charge from cast-off clothes, shoes and accessories that were left there.

General Wastemoreland earned his five stars in Cotati. At his urging, the City Council declared the city a national monument, something which Wastemoreland hoped would prevent high-rise apartments from being built. He failed a few weeks later to get a resolution passed to seek federal recognition. Vice Mayor Henry Fassin stormed out of the meeting, calling the plan “Ridiculous.”

In Cotati, Wastemoreland became vocal about socialism. “Capitalism is direclty opposed in Christianity. Socialism is the country’s savior.”

In 1977, Wastemoreland was hit crossing a street by a drunk driver with no lights. He sustained multiple broken bones and suffers still from short-term memory loss.

He moved with Ginger back to Berkeley.

The environment in which General Wastemoreland once thrived had changed. He slowly faded away and Tom Dunphy the conscientious pacifist Catholic emerged.

He did work for the Native American Health Center in San Francisco, and helped out at the Saint Anthony’s Foundation. He has taught Latin and Greek at the North Berkeley Senior Center.

He remains an observant Roman Catholic, and for decades has attended mass at St. Joseph the Worker Catholic church on Addison in Berkeley, around the corner from where Dunphy lives.

Dunphy was a friend and admirer of Saint Joseph’s Father Bil O’Donnell O’Donnell was a giant in the world of peace and social justice activism. In this photo above he stands with Dolores Huerta. We in the United Farm Workers knew that we had no better warrior/friend in the world than Father Bill.

For years Wastemoreland worked with Jose Luis Parada and the Sociedad Procultura Salvadoreña in San Francisco. Parada came to the United States from El Salvador in 1969. In the 1980s, he and several Salvadoran friends created La Sociedad Procultura Salvadoreña. Their mission was to promote the culture, art, poetry, literature, and music of their homeland.

Parada was a poet whose work Oasis Wastemoreland translated into English. Parada died in early 2018. The Center closed years ago.

Dunphy/Wastemoreland is at times associated with the Yippies. It is an association or comparison that seems on its face to be valid, but it only goes so far. Like the Yippies, Wastemoreland was a highly theatrical, anti-authoritarian practitioner of street theatre and symbolic politics. Unlike the Yippies, who were grounded on pop culture, the excesses of the 1960s counterculture, and a naked anti-authoritarianism, Wastemoreland was grounded in Roman Catholicism and pacifism. He was ours for much of his anti-military career. People who were here then light up when I mention his name. He was a beacon in a chaotic and troubling time.

He lives a quiet life now, surviving on disability payments.

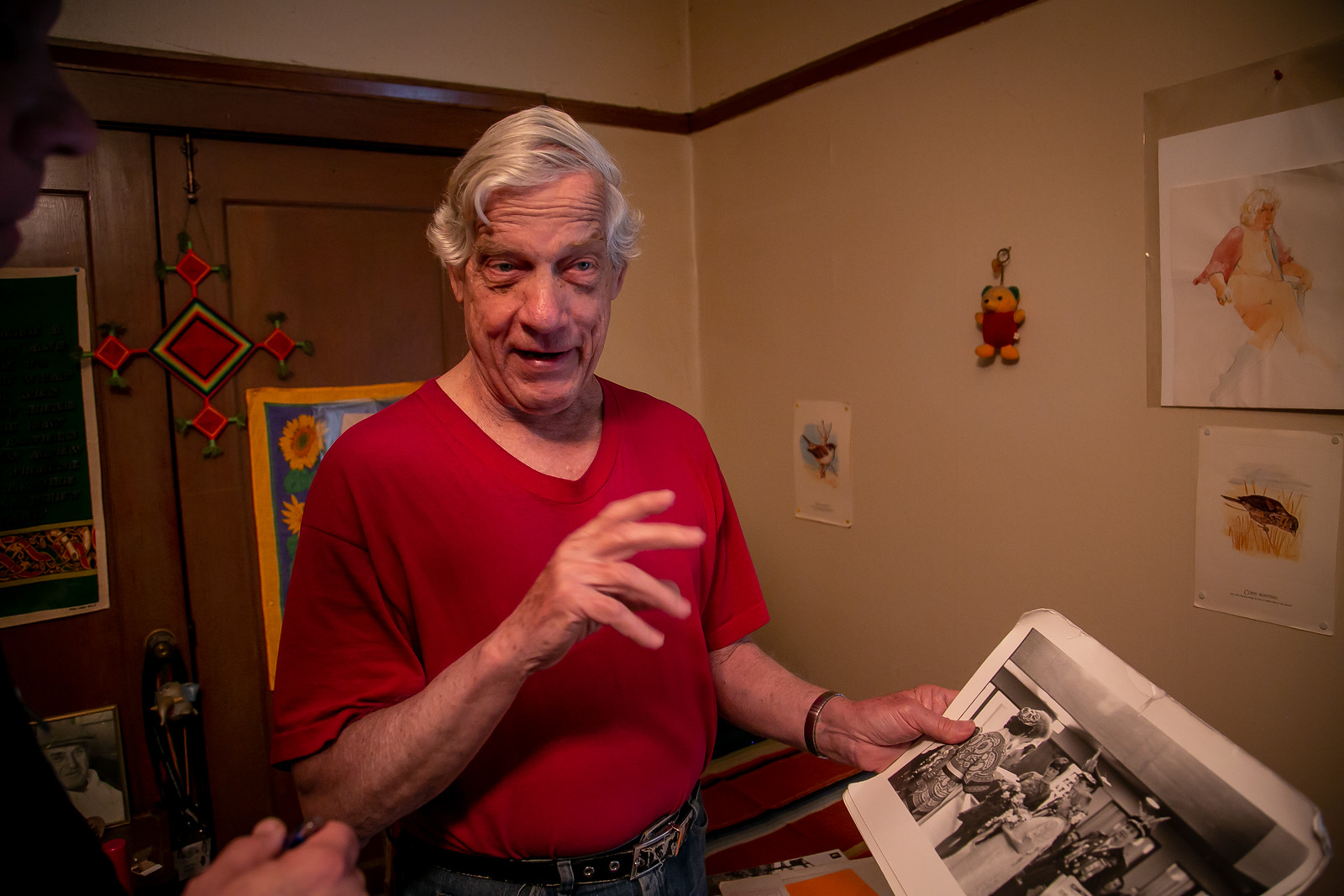

His uniform is archived at Cal, but he has his photographs and letters and poems and books. And memories.

On Jefferson just south of University, near his apartment, a mural celebrates him.

I showed the draft post to my friend. He read it. He put on a song. He said, “Righteous dude if there ever was one.” He handed me a photo.

He had gone for a walk near Indian Rock. He has a special inlace in his heart for goats and was very happy about what he had seen.

That’s well and good. What about the post?

P.S. These are the other Pink Floyd posters I had the restraint not to show you.

Hopi Princess? Native American tribes & communities did not have royalty!

Tom was a great friend and mentor in Cotati. I had many hours of conversation and fun with him, not to mention political activity for Peter Plate and I had written the first rent control ordinance passed by the California Supreme Court.

It was Peter, myself and others who fought against condominiums and high rises.

Tom was always there.

Be well, Tom

Danny

On another note. The General moved to Cotati in 1979. He lived at Veto’s for a while a while and then moved to Arthur Street, near the hub. He lived next door to me and down the road from Ricky Appelbaum, the father of Jake Appelbaum. He came up to Cotati with Buck Chapman, a poet from Berkeley.

We were in the fourth year of a fight for rent control and the General was a frequent ‘guest’ at the City Council meetings.

We had great theater at City Hall ever secon Tuesday from 75-80.

We passed rent control and also an initiative to stop condo building which was later overturned by the Appellate Court of California.

To, if you read this, contact me at: weilunion@aol.com

Danny Weil