I am, I admit, a tad UFW-centric. I spent the summers of 1968 and 1970 working for the Union, and then was full time from 1972 until 1980. I was 16 when I went to Delano. I was 28 when I left.

Those are big years in a person’s life. The picture above was in Coachella, in the early weeks of the 1973 grape strike. The Union made a movie about the strike, a very good piece of propaganda.

These were amazing weeks. If you click on the photo you will get a feel of what it was like. At 2:25 I start talking. This short scene has been used in many subsequent movies about the Union.

I owe my quick thinking to a problem that I was asked to solve during an interview for Harvard at the Union League Club in Philadelphia by Brian Leary’s dad. It involved four cubes of sugar. The challenge was to make them all equidistant from each other. You needed to go up in the air to solve it.

I got the problem but didn’t get into Harvard. What would I do with the Harvard bag that my parents bought me in second grade because I wanted to go to Harvard? Enough about me.

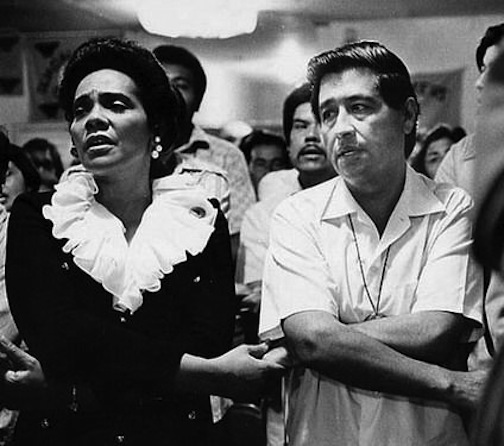

Except in California where we held out own in the public mind, we lived in the shadow of the civil rights movement. I don’t think that Cesar ever met Dr. King.

He did meet Mrs. King and Jesse Jackson though.

The bus was iconic in the civil rights movement, and to some extent in the farm workers movement.

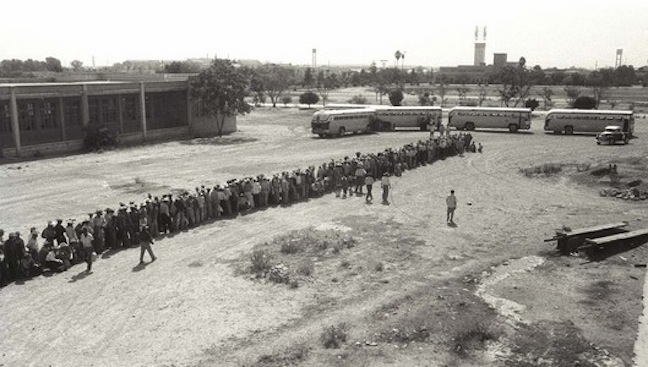

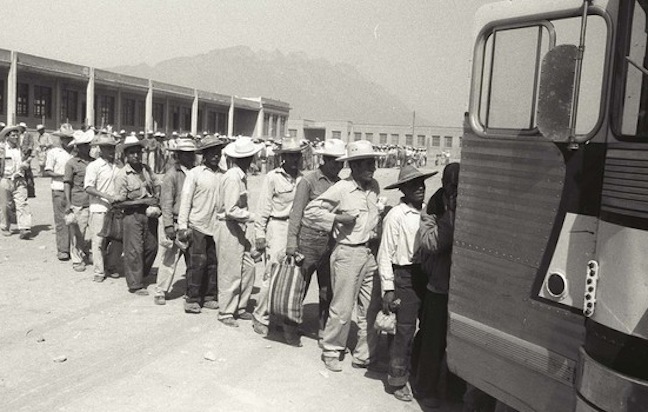

In the 1950s and early 1960s, much of the farm work done in California was done by Mexican workers under negotiated administrative agreements sanctioned by Pubic Law 78. The workers were known as braceros.

They came from Mexico in buses.

At the end of the harvest they went home on buses.

Others were deported. These men were swept up in “Operation Wetback” in 1954 and sent back to Mexico in buses.

During and after the bracero program, the farm labor bus was emblematic of the harsh conditions under which farmworkers lived.

You should see the buses in Calexico between 3 and 5 in the morning. Hundreds of buses. Workers cross from Mexicali by foot and walk to parking lots and alleys where the labor contractors and growers have buses waiting to take them to the fields, maybe ten minutes away, maybe two hours away. The energy of those several very-early-morning hours is really something.

You should see the buses in Calexico between 3 and 5 in the morning. Hundreds of buses. Workers cross from Mexicali by foot and walk to parking lots and alleys where the labor contractors and growers have buses waiting to take them to the fields, maybe ten minutes away, maybe two hours away. The energy of those several very-early-morning hours is really something.

It makes you think of the docks, on the waterfront.

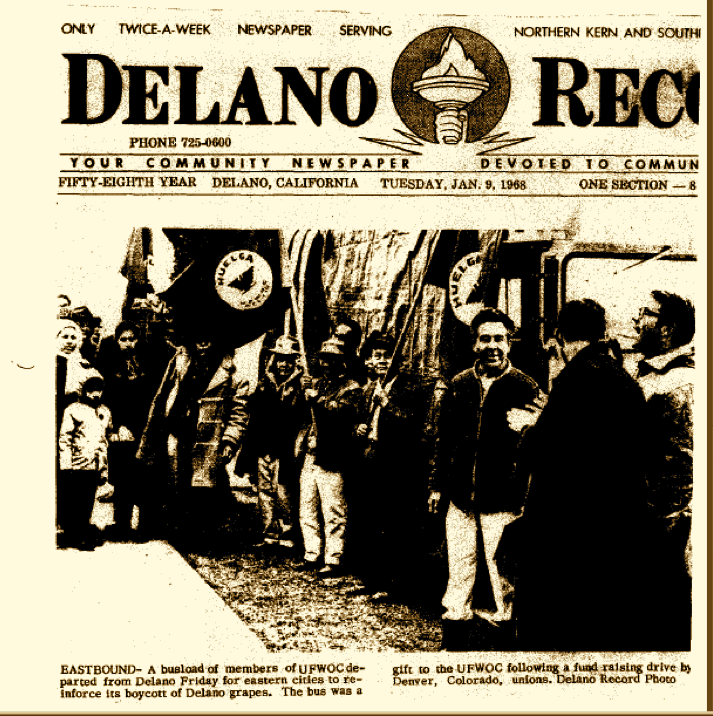

If there was one bus that symbolized the United Farm Workers in the 1960s it was the unheated school bus that in January 1968 left Delano full of farm workers and volunteers. They all went to New York, were trained by Fred Ross, and eventually they fanned out to cities across the United States and Canada to open boycott offices. It was a long and cold ride. They each started from scratch in a city they didn’t know. Two years later they and those who followed had built the most powerful consumer boycott in American history and had through the boycott succeeded in forcing California grape growers to sign contracts.

One of the first-wave boycott leaders was Marion Moses, shown here at the top left of the photo. She was in charge of the Philadelphia boycott when my high school chaplain, the Rev. Alexander McCurdy, made contact with the UFW on my behalf. I met Marion. I walked in cold Philadelphia winter picket lines. And then went to Delano that summer. I finally left in early 1980.

In 1973, contracts won by the boycott in 1970 expired. Rather than renew the contracts with us, grape growers in the Coachella Valley did what lettuce growers in Salinas had done in 1970, they signed sweetheart contracts with the Teamsters. In mid-April we went on strike. It would be a long a brutal summer of strikes. Thousands of strikers would be arrested, two strikers would be killed, and we would lose virtually all our contracts.

A few days after the strike started, we got help from Salinas.

It was a beautiful day, maybe 80°, and the Valley smelled like citrus blossoms. Four chartered Greyhound buses and a couple dozen cars with Salinas lechuegeros (lettuce cutters) and vegetable workers, calling themselves the Division del Norte (the army led by Pancho Villa during the Mexican Revolution, which with 50,000 men was the largest revolutionary force ever amassed in the Americas), arrived to lend their special brand of tough love to the strike. There was incredible fanfare, mariachis playing ballads from the Mexican revolution, cheering.

The next day, when the buses pulled up to the picket lines the men were pulled off one by one and arrested.

They were booked in the field and then loaded one-by-one into a Riverside Sheriff’s Department bus for a defiant ride to the jail in Indio.

At the jail, the UFW’s crack legal team got them all out. No lawyers needed. Just legal workers Harriet Teller and moi. And then the Division del Norte got back on their chartered Greyhounds and went back to Salinas.

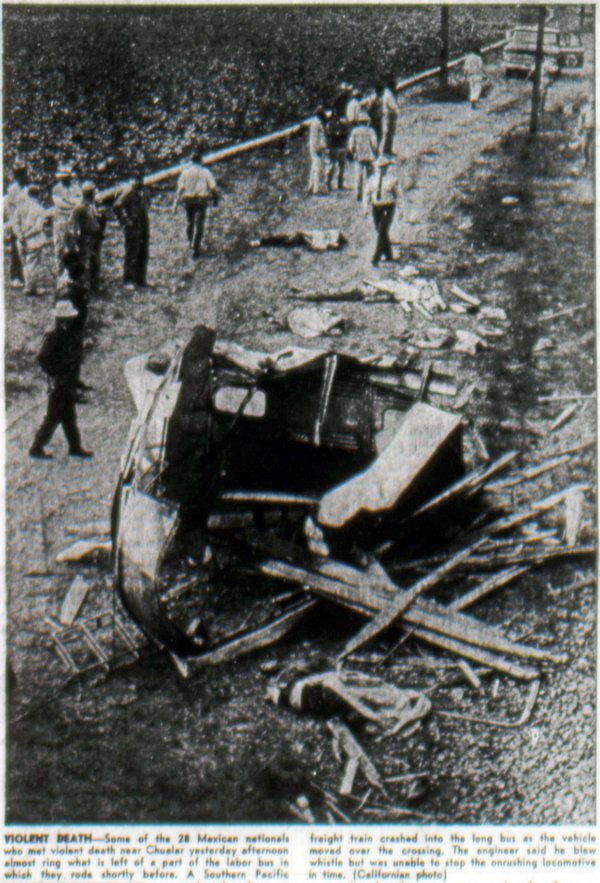

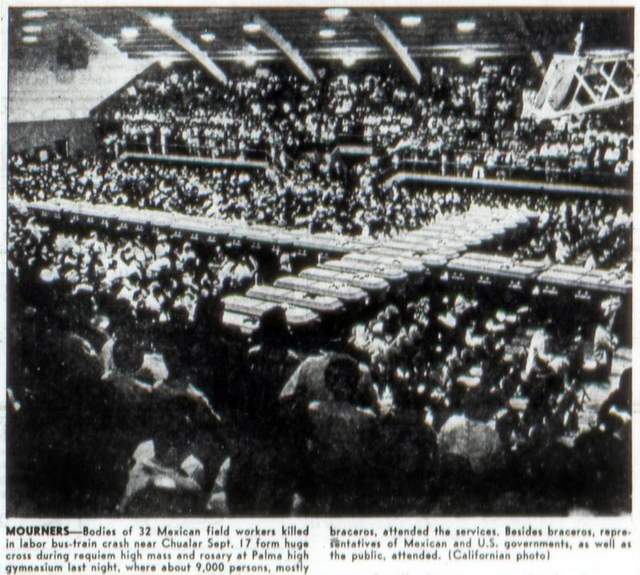

You saw the farm labor buses above. Tragedies are inevitable when human life is so unvalued. There was a terrible bus-train collision south of Salinas in 1963.

In 1963, a bus carrying braceros was struck by a train and 18 were killed. A large memorial service was held in Salinas. Eleven years later:

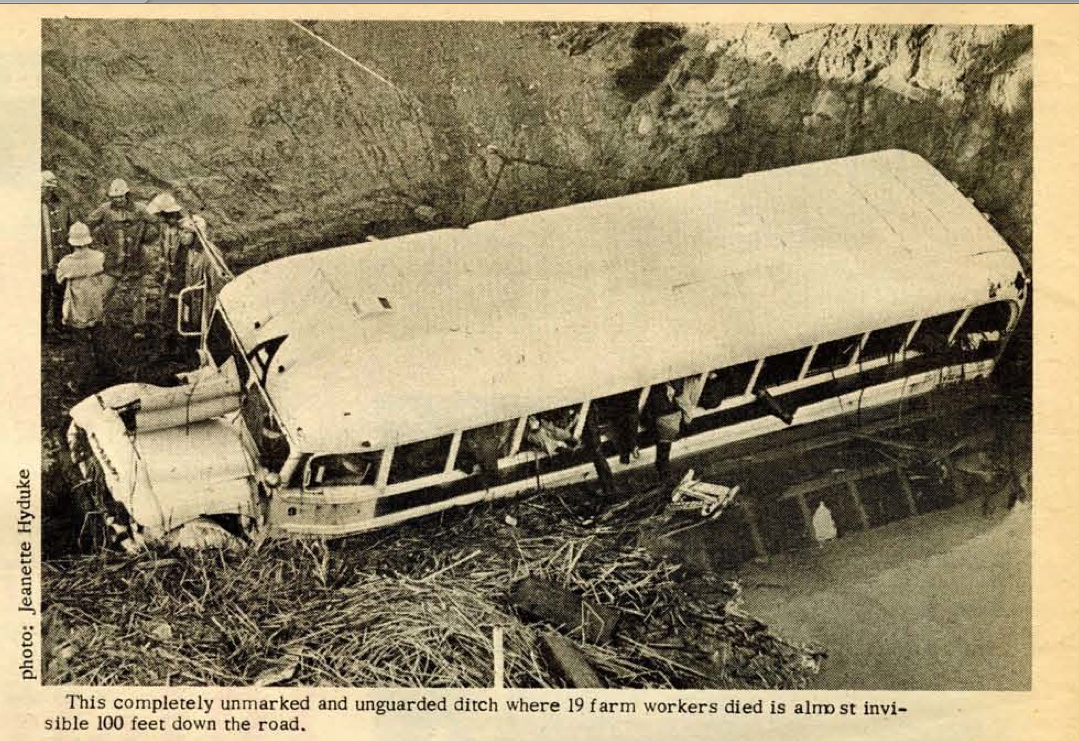

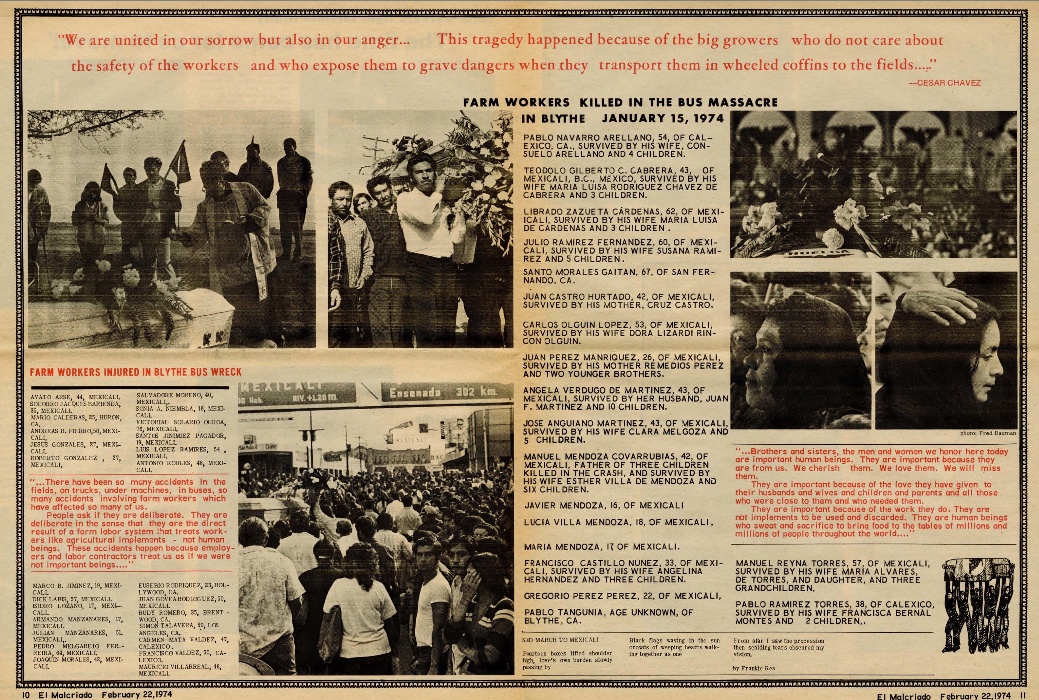

In January 1974, a bus carrying farm workers from the border crossing in Calexico to work in Blythe – 100 miles away, four unpaid hours a day – drove into an irrigation ditch and 19 workers drowned.

The UFW organized a massive funeral march from Calexico across the border into Mexicali. The sight of all those coffins lying together was a real shock.

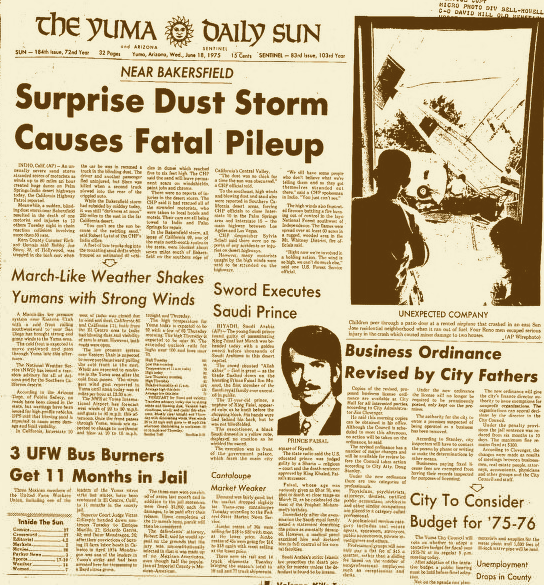

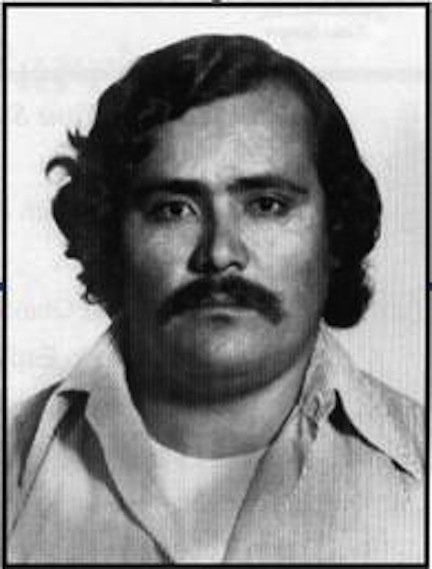

Later in 1974, threel men associated with the UFW were arrested in Calexico and charged with arson and attempted arson in conjunction with fires at 11 farm labor contractor buses in the midst of a near-constant strike in the Imperial Valley that had spilled over into a lemon strike in Yuma.

In 1975, the men were convicted and sentenced to jail, despite a vigorous legal defense.

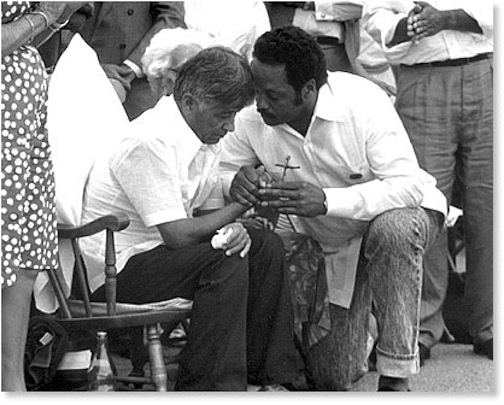

Two had great nicknames, and we didn’t really know them except by their nicknames – Calacas (“Skeleton” or “Bones”) and Compa Oof (“Brother Oof”). The third man was Oscar Mondragon, who after being released from jail became a lieutenant for Frank Ortiz (to the right of him in the photograph above) and then was placed on the UFW Executive Board. The Landrum-Griffin Act precludes convicted arsonists from holding union office, but Landrum-Griffin, like the National Labor Relations Act, does not apply to farm workers.

In an essay that he wrote for LeRoy Chatfield, Mondragon said simply: “When the strike started, Manuel Chavez asked me to help him run the strike. Before the lemon strike is when I got arrested in Calexico. We were accused of three counts of arson and 11 counts of attempted arson. We were arrested, tried, and sent to jail for 11 months altogether.” Oscar and I were on opposite sides of the Final Battle within the UFW, but I always got along with him and I see this essay as stand-up. He didn’t deny, and at trial didn’t rat out anyone.

That said, this was not the finest bus moment in our history.

We were in huge trouble in 1974. We had lost almost all our contracts. We had spent a fortune in the losing strike of 1973.

Then we were able to push through farm labor legislation in Sacramento with the newly elected Governor Brown signing it in 1975. On August 28th, the Agricultural Labor Relations Board would accept petitions to hold representation elections.

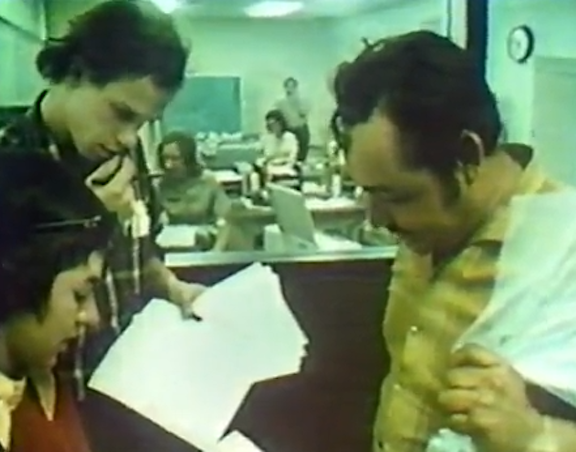

This photo was taken on August 28th, 1975 in Fresno, in front of the Agricultural Labor Relations Board office in Fresno. Left to right: Glenn Rothner (attorney), moi (not yet attorney), Barry Winograd (attorney), and Ben Maddock (organizer). We were filing the first petitions for elections.

There was a ton going on. Massive organizing drive – something that we had not done much of over the years. On the other side: the growers and the Teamsters, formidable opponents.

In the middle of all that, Cesar decided to march around the state.

Here Cesar is marching in 1975, his press spokesman Marc Grossman to the left, Ana Murguia to the right. Marc thought the march was a great idea.

He compared it to Mao’s Long March in 1934. When Cesar came through your area you had to stop what you were doing for a week and get ready for him to come through – rallies, places to stay, food, etc. This was a huge distraction.

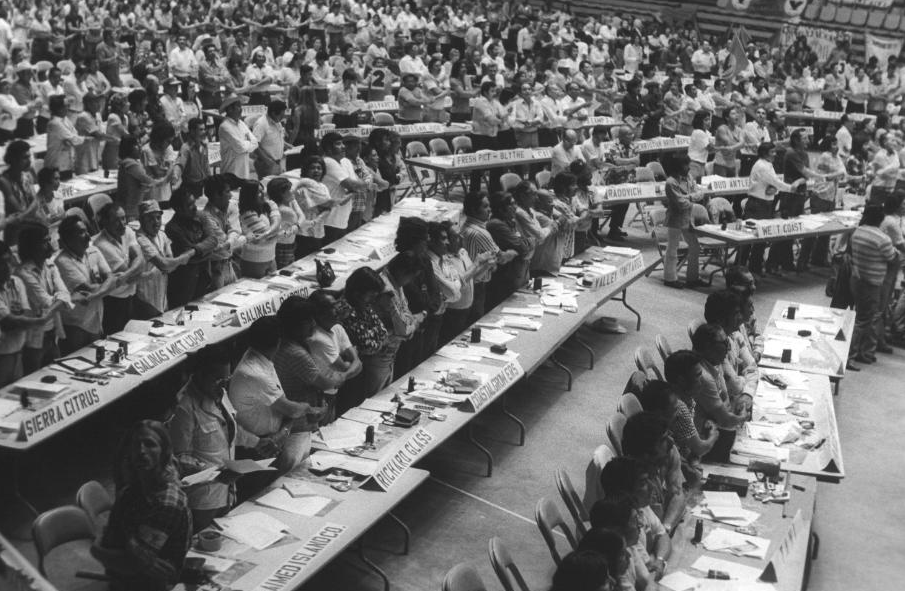

But it was not the end of distractions. Our convention was scheduled for August in Fresno.

In the middle of all that we were trying to do, Cesar decided that it would be a good idea to (1) buy a fleet of used Greyhound buses, (2) train a couple dozen people as bus drivers; (3) send the fleet out across the United States and Canada with three drivers per bus; (4) send out all the mechanics to fix the buses when they broke; (50 bring everybody working on the boycott to California for the Convention; and (6) repeat process to take them home.

It was a good convention. The people who had ridden the bus there looked pretty whooped. The drivers looked worse than whooped. Then they all got back on the buses and drove back east and then the drivers drove back west. The drivers and mechanics were wasted by this experience. Some drove upwards of 10,000 miles in two weeks. Brutal!

And then the buses?

They sat at La Paz, the Union headquarters in the Tehachapi Mountains. Rarely if ever used. For a while the mechanics cannibalized them to keep one or two running but then that stopped.

The last time that I went to La Paz was in 1982, two years after being fired for the last time. I went with Jerry Cohen to meet with Cesar about a lawsuit against the Union that named me as a racketeer. Yes! It was a cordial meeting. The place looked terrible. And the rusting, slutted out old Greyhounds were still there.

This photo is from La Paz in 2005. This is not a Greyhound, but it is a bus. Obviously. Same idea.

We had elections! Despite all the distractions, we won elections! Less than two years later, in 1977, the Teamsters agreed to get out of agriculture. We had an open road – a good law, lots of members, a good Board administering the good law, and no competition. What could go wrong?

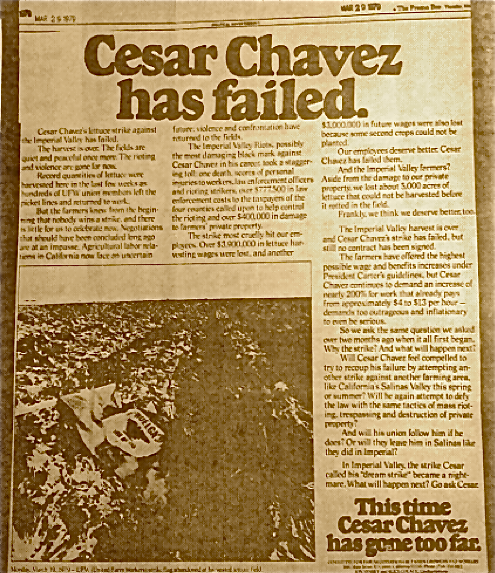

In early 1979, our lettuce contracts expired. The vegetable industry decided to hardball us. We went on strike, a huge lettuce strike in the Imperial Valley.

In February, grower supervisors shot and killed an unarmed striker, Rufino Contreras. On the day of Rufino’s funeral, nobody worked in the fields in the Imperial Valley. Nobody. It was called a paro de luto, a stoppage of mourning.

When the lettuce harvest ended in the Imperial Valley, the work and strike moved north to Salinas. We hit them very hard all summer in Salinas.

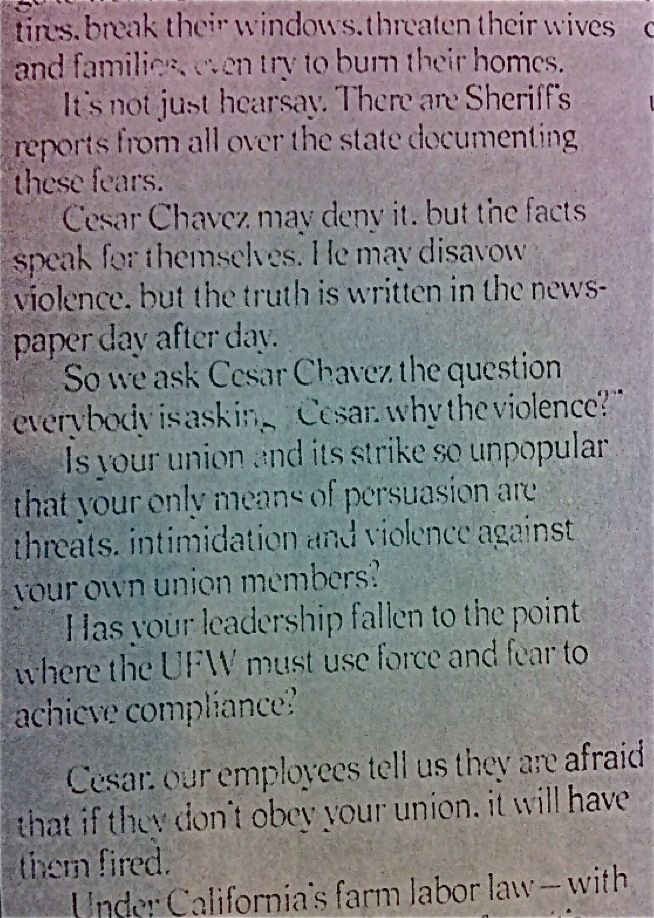

The growers felt the pressure. The placed advertisements in the local newspaper attacking Cesar.

They said that the union had over-reached, that we were failing.

They pushed stories in the press accusing us of strike-related arson.

Best of all, and most relevant to here, they filled a corner lot with burned out, bombed buses. They said that we did it! There was a great big billboard, asking if this was what we meant we said that we were non-violent.

It may be a false memory, but I remember newspaper ads with photographs of the lot filled with the bombed buses.

I can’t find a photo. Smart people who know how to find photos have not found photos. But I know this – there was a vacant lot full of destroyed farm labor buses.

They thought they had us in a corner. We won the strike though. And in the course of winning it, we entered the last phase of the Final Battle within the Union. Which we lost.

I am biased, I know, but I think that this is a respectable amount of material about the legacy of the bus within the farm worker movement. I went to show the material to my friend.

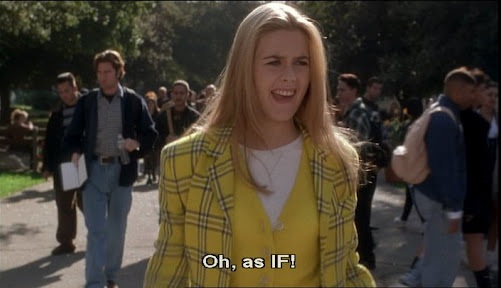

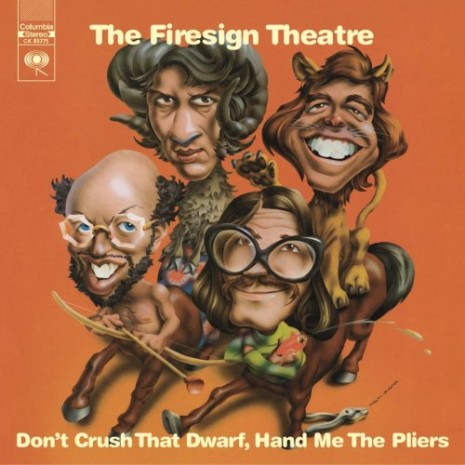

He was listening to Firesign Theatre. “Presenting honest stories of working people as told by rich Hollywood stars” was one of his all-time favorite lines. He showed me a photo.

It is from Blonde on Blonde. He suggests that these are the pliers to which Firesign Theatre referred. Before I could ask him about the bus material he started rattling off all the literary and cultural allusions in “Desolation Row” – Cindella, Bette Davis, Romeo, Cain and Abel, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the Good Samaritan, Ophelia, Noah, Einstein, Robin Hood, Phantom of the Opera, Casanova, the Titanic, Nero, Neptune, Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot. He can exhausting sometimes.

I got his attention and showed him the material. “You got a theme working here for sure. You dig themes. You have a thematic mind.” What does he think?