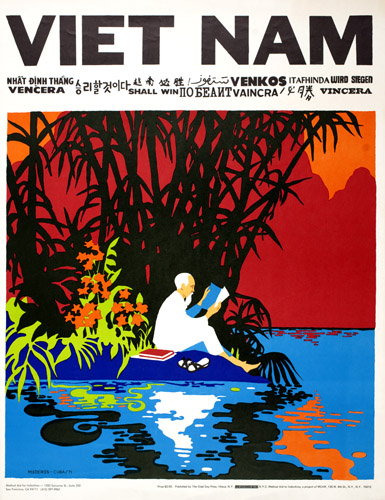

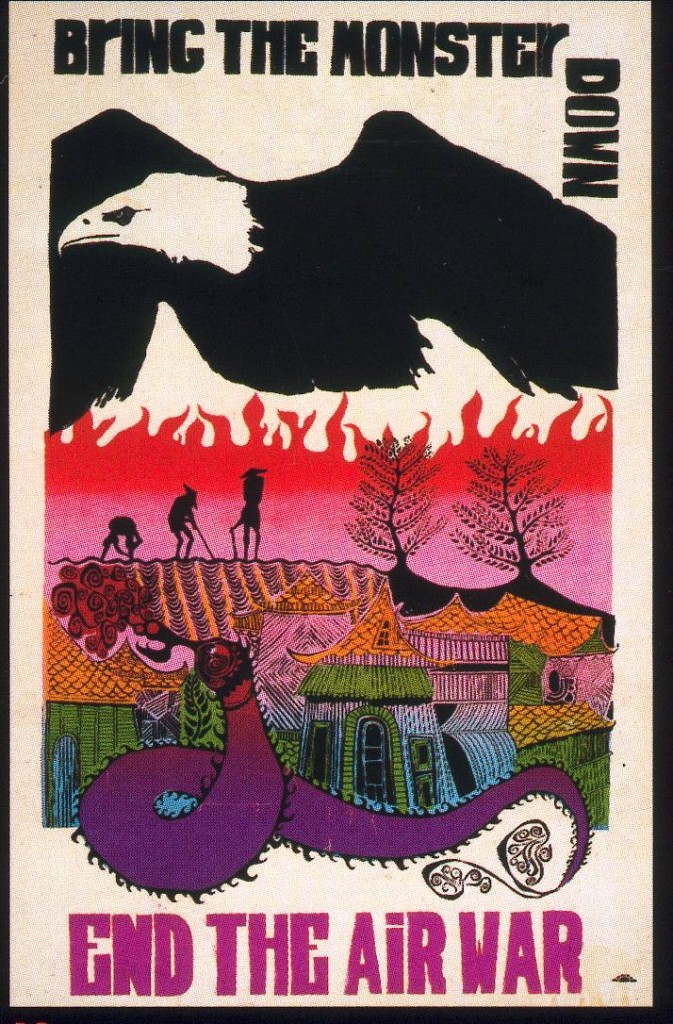

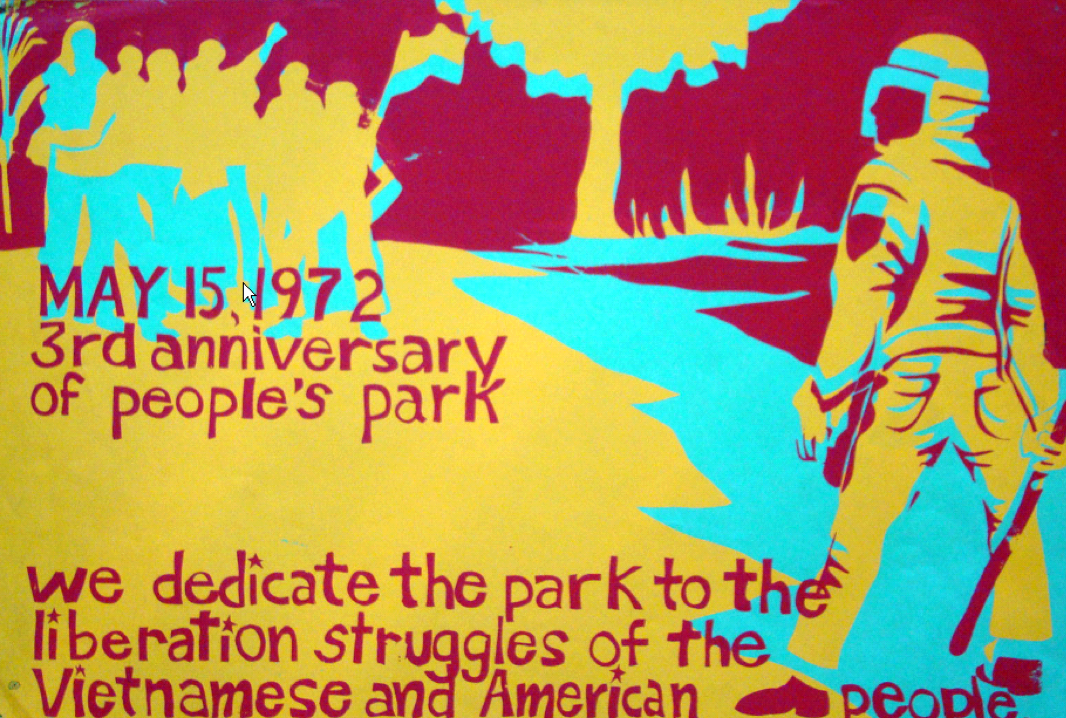

By Rene Menderos, Cuban artist who visited Vietnam several times and helped produce posters there; printed by Glad Day Press, Ithaca, New York, 1972, fundraiser for Medical Aid to Indochina

The late 1960s and early 1970s were a Golden Age of posters. Pop art intersected with rock and roll that intersected with protest and social movements. Hundreds, even thousands of posters relating to social change, manifested by political activity or cultural markers such as music, were there for the taking, free or very cheap.

Much has been written about the flood of political posters in the 1960s/1970s. For example:

The Sixties Project reflects on Political Posters from the United States, Cuba and Viet Nam, 1965-1975.

Lincoln Cushing wrote this Survey of San Francisco Bay Area Political Poster Workshops, Print Shops, and Distributors and this article on The New Left Printing Renaissance of the 1960s – and Beyond.

Free Speech Movement activist Michael Rossman donated his collection of political posters to the Oakland Museum, which archives them digitally. Rossman wrote extensively on political posters; his writings are indexed here.

What is presented in this post is the collection of posters that hung at one time or another at the Red Sun Rising collective on Parker Street. There were hundreds more, maybe thousands more, but that isn’t the point. This is not a complete gallery. This is what these young Cal students in one collective found inspiring. The breadth and diversity of issues which they embraced is mind-boggling. Where is that diversity today?

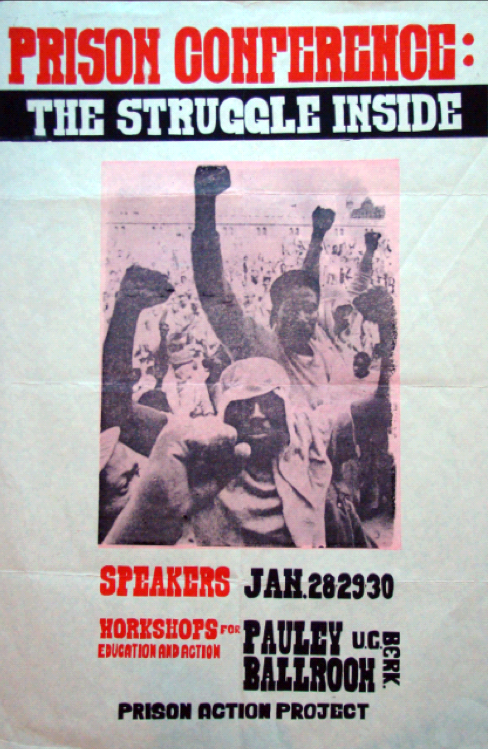

This 1972 poster was probably the most successful poster printed by East Bay Media. Doug Lawler, the first citizen of East Bay Media, designed the poster. It was the policy of East Bay Media not to identify the artist, or even itself as the print shop. They were an early Anonymous. Collective members included Peggy White, Harold Lucky, Stephanie Jones, Suzanne Korey, and others. They first operated out of a garage on Regent, and then when the Tribe ceased operating they moved into the Tribe office at 1701 Grove. They printed the posters on a Chief 200 offset press in a garage on California Street.

The image in this poster is from the Attica Prison Uprising/Riot (what you called it revealed your politics) of September, 1971. Over a four day period in which prisoners controlled the prison and then were subdued, 33 inmates and 10 guards and prison administrators were killed.

The image in this poster is from the Attica Prison Uprising/Riot (what you called it revealed your politics) of September, 1971. Over a four day period in which prisoners controlled the prison and then were subdued, 33 inmates and 10 guards and prison administrators were killed.

Attica (whose cultural significance today may be buried in Al Pacino’s stunning performance in Dog Day Afternoon) ignited in response to the killing in California on August 21st of prisoner and revolutionary George Jackson at San Quentin. Six inmates at San Quentin were charged with crimes arising from the attempted “escape” by George Jackson – Hugo Pinell, Willie Tate, Johnny Larry Spain, David Johnson, Fleeta Drumgo and Luis Talamantez. They became known collectively as the San Quentin Six.

The Left, especially in California, and more especially the Bay Area, were inspired by the self-proclaimed revolutionary ideology among California inmates. They remembered Marx writing that prisoners were capable of “the most heroic deeds and most exalted sacrifices.” They were especially inspired by Ho Chi Minh’s saying that “when the prison gates fly open, the real dragons will emerge.” The Left embraced the San Quentin Six and provided support for their legal defense on many levels. After a 16-month trial, one was convicted of murder, two of assault, and three were acquitted.

The radical prisoner movement rose in the early 1970s and largely subsided by late in the decade. Further reading? Here.

Over defiance of authority may be glamorous and romantic, but it often falls into what Saul Alinsky described as “pointless sure-loser confrontation.”

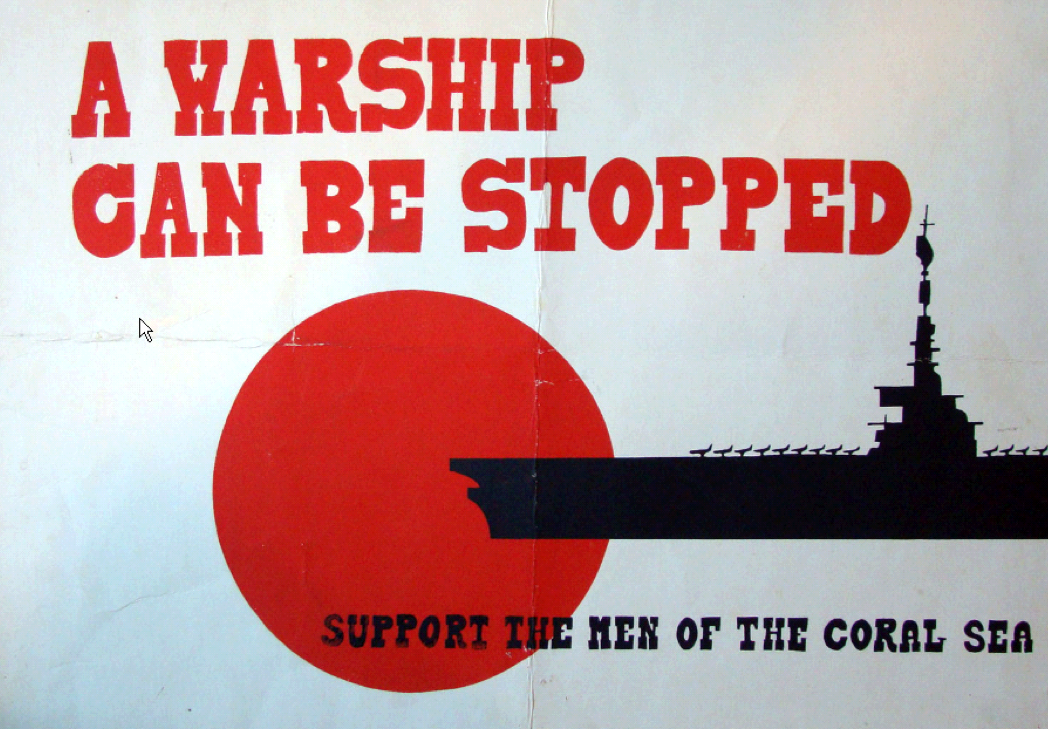

As morale fell among U.S. troops in Vietnam, open defiance of authority increased. The most well-known manifestation of defiance was fragging, the intentional killing of an officer who was too aggressive with the lives of his charges. Mutiny was rare, but did happen and it did happen a few miles from Berkeley on the U.S.S. Coral Sea.

The Coral Sea was docked in Alameda in the fall of 1971, scheduled for a tour of bombing duty in Vietnam. A core of crew members launched a petition-drive that built into a movement known as “Stop Our Ship” or SOS. The petition said: “We the people must guide the government and not allow the government to guide us! The Coral Sea is scheduled for Vietnam in November. This does not have to be a fact. The ship can be prevented from taking an active part in the conflict if we the majority voice our opinion that we do not believe in the Vietnam war. If you feel that the Coral Sea should not go to Vietnam, voice your opinion by signing this petition.”

The Left in Berkeley rallied behind the sailors and SOS. Crew members took part in anti-war demonstrations, including a large contingent at an anti-war rally in San Francisco on November 6, 1971.

The ship sailed, the movement spread to other carriers, and in a year later the war ended. Further reading? Here.

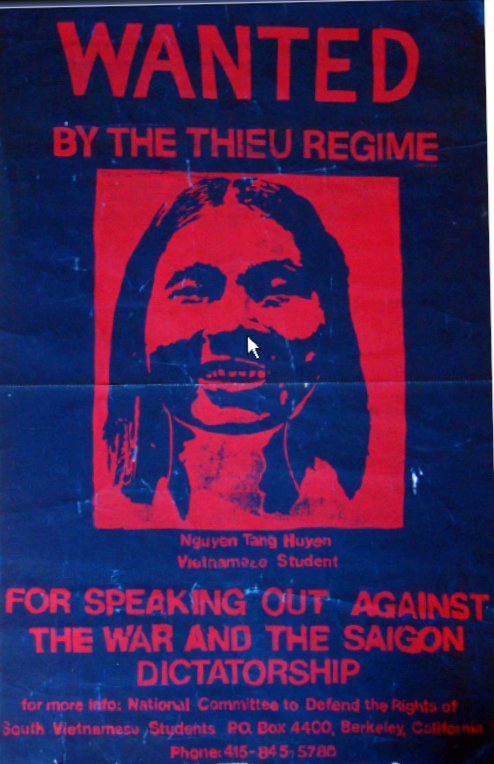

This is a Red Sun Rising production. Nguyen Tang Huyen was a Vietnamese Student studying psychology at Cal. He came to the United States in March, 1968, with a scholarship from the Agency for International Development. He graduated in honors and in 1972 had been accepted for graduate work in clinical psychology at Case Western. Because Huyen spoke out against the war, the Thieu regime in Saigon asked the US government for his immediate return to Vietnam. The government terminated his scholarship and initiated deportation proceedings.

Later in 1972, Jane Fonda visited Hanoi and in a radio address spoke of Vietnamese students facing deportation from America: “We have come to know something about your country because in the United States there are students from the southern part of Vietnam, from Saigon, from Hue, from Danang. They have taken a very active stand against the war, and they are speaking out loudly to the American people and explaining to us that Vietnam is one country with one culture and one historic struggle and one language. As a result of their protest against the war, the repression of the U.S. Government and the Saigon clique is coming down on their heads as well. For example, in the first week of June, four of the students received letters from the U.S. State Department saying that their AID scholarships had been terminated as of June 1, and that tickets were waiting for them to take them back to Saigon on orders of the Thieu regime.”

The plight of anti-war South Vietnamese students was the backstory to a national story when Ngyuen Thai Binh was shot and killed on July 2, 1972. in the course of a half-hearted attempt to divert to Hanoi the airplane taking him back to Saigon and almost-certain death there.

Berkeley radicals accepted Nguyen Tang Huyen as one of theirs. He campaigned for asylum from his apartment on Dana Street.

Congressman Ron Dellums sought political asylum for him. A committee was formed to support him, the National Committee to Defend the Rights of South Vietnamese Students with a Berkeley post office box address.

My research has not led to an understanding of how this story ends. Do you know? Was he granted asylum? I don’t know. A little bit more is here.

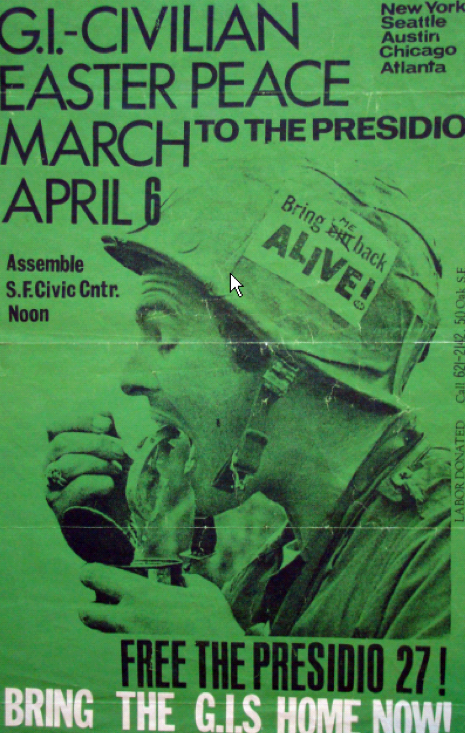

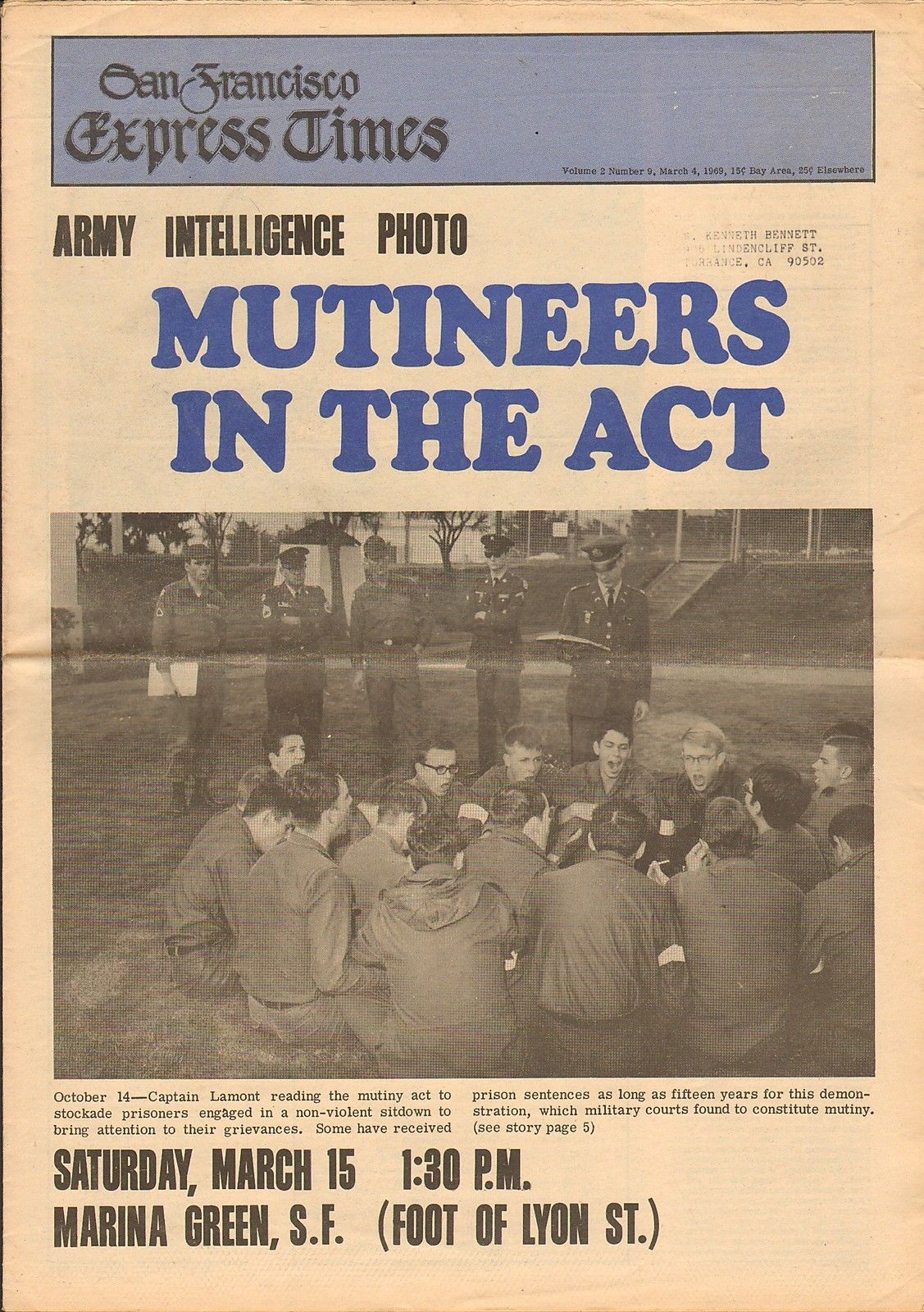

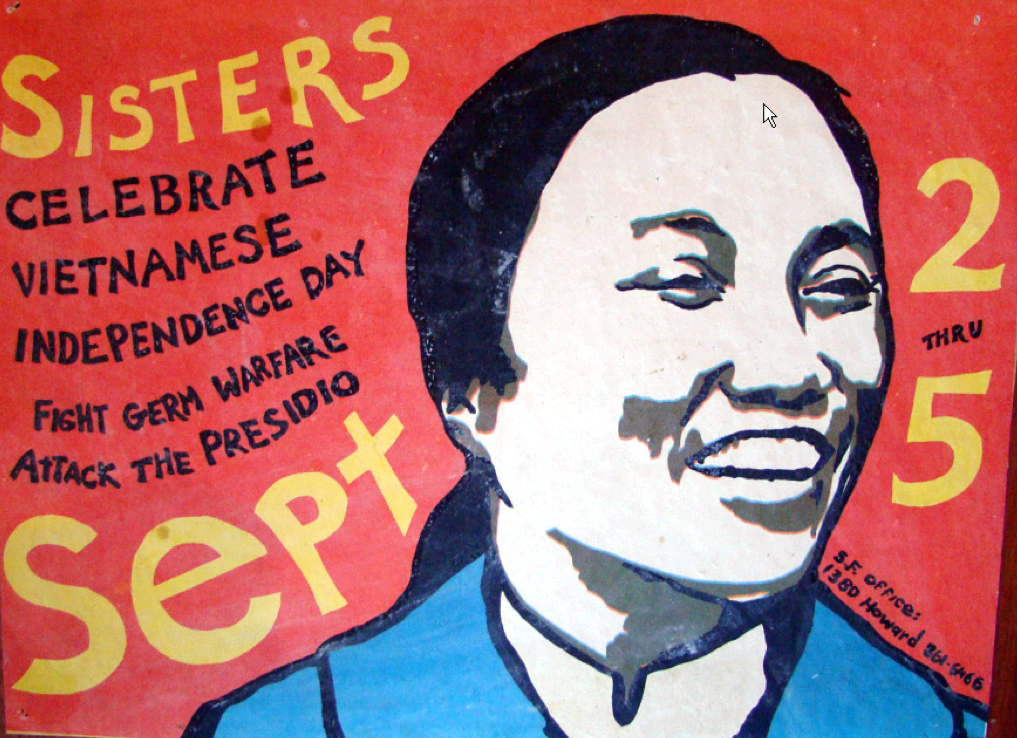

Back to resistance within the armed forces – the Presidio 27 were prisoners at the Presidio stockade in San Francisco. On October 14, 1968, the 27 (plus one who backed down) engaged in a sit-down strike and ignored orders to disperse. Walter Pawolski read their demands – improve prisoner conditions and end the war.

They were charged with mutiny. The first defendants to go through court martial proceedings received sentences of 14-16 years of hard labor.

Their resistance drew national attention and sparked public condemnation. Anti-war GI’s organized a march to the Presidio on April 6, 1969.

This demonstration took place before most of the members of Red Sun Rising matriculated at Cal. It was a historical relic. If you want to know more, read this or buy this:

In 1970 the Court of Military Review voided the long sentences and imposed instead shorter sentences for willful disobedience of a superior officer. Most were released that year. Three had escaped to Canada.

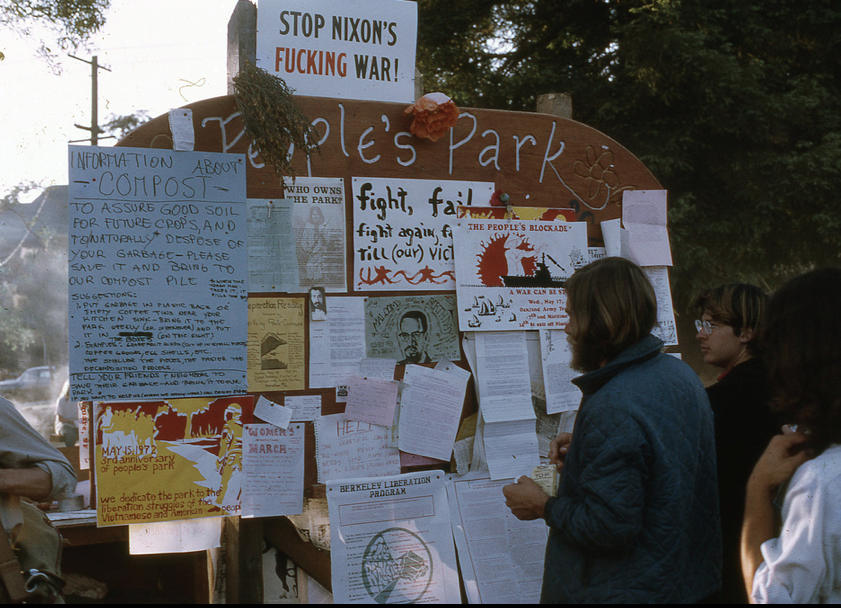

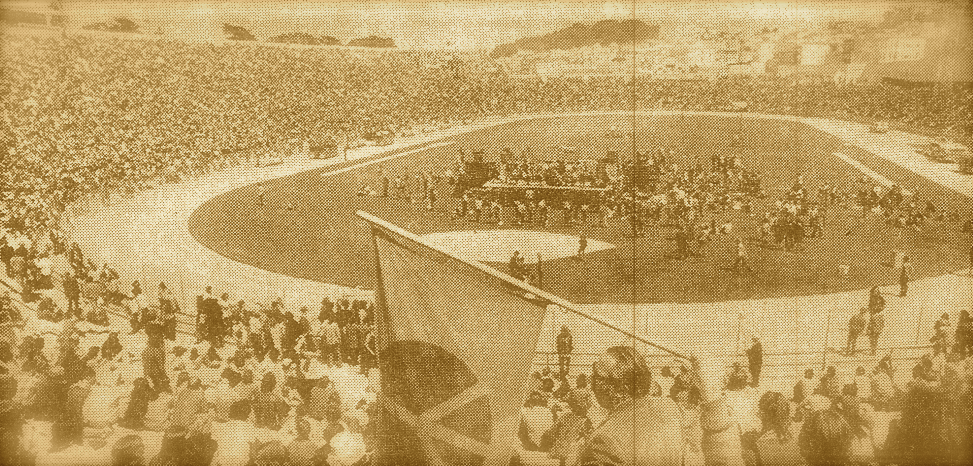

By 1972, it looked like a parking lot and soccer field would be built at People’s Park. In May, protestors responding to President Nixon’s announcement that the United States would mine North Vietnam’s main port – Haiphong – tore down the chain-link fence around the park perimeter. Happy anniversary!

This photograph is from the celebration. It is good to see this and to remember what People’s Park once was. Before what it is now.

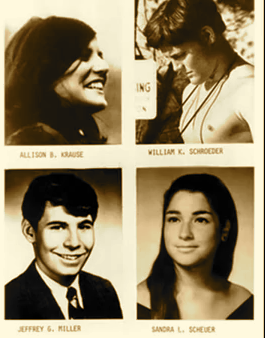

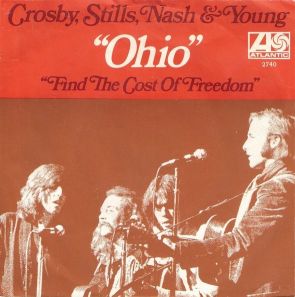

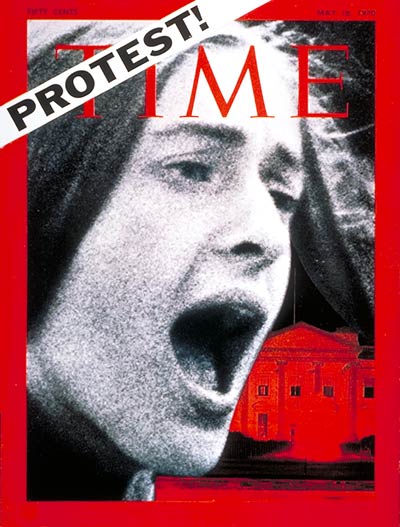

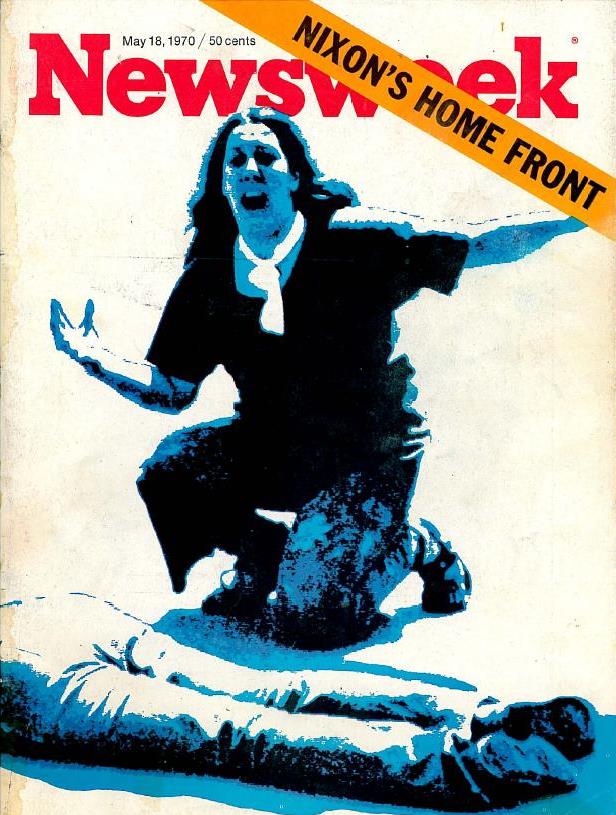

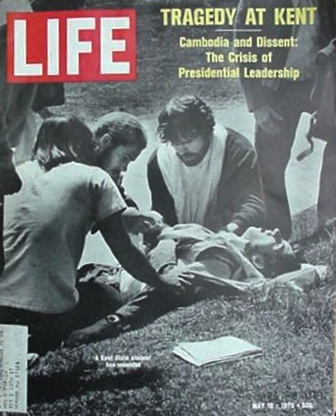

On May 4, 1970, the Ohio National Guard shot 13 unarmed students. Some were walking to class, some were observing the protest, and some were protesting the American invasion of Cambodia which President Nixon had announced on April 30th.

Four died. Of the wounded, one was paralyzed for life. It was a time of horror for the country.

Four died. Of the wounded, one was paralyzed for life. It was a time of horror for the country.

The media focused on the victims.

President Nixon said, “I hope they provoked it.” Governor Reagan promised a bloodbath. They didn’t get it. The Left focused not on the victims, but the killers.

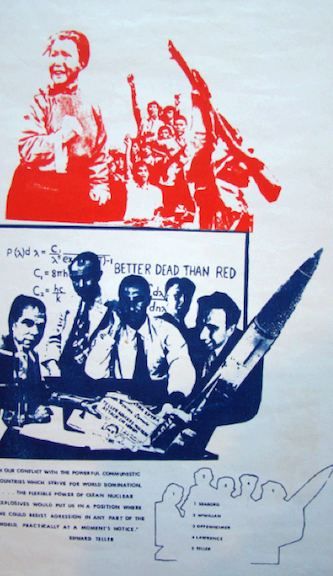

This poster is unusual – it does not reference a specific event or group or issue. Created by Bruce Kaiper of the East Bay Media Project in 1970, it suggests a war crimes tribunal. The words in the lower left are those of Edward Teller: “In our conflict with the powerful communistic countries which strive for world domination, …. the flexible power of clean nuclear explosives would put us in a position where we could resist aggression in any part of the world, practically at a moment’s notice.” Teller had recently advocated using nuclear weapons against Hanoi, as we are reminded by the headlines in the newspaper shown in the poster.

A former Red Sun Rising member explains the campaign: “The War Crimes Tribunal was actually the idea of Tom Hayden and Red Family to protest Berkeley faculty’s direct complicity with the war including scholars such as Richard Scalapino, a southeast Asia expert who worked with the National War College and the Pentagon. We audited his class but several students were suspended for disrupting it. At that time many social scientists, from anthropologists to political scientists, directly worked with CIA/military.”

The five identified as war criminals were all nuclear physicists or chemists who took played key roles in development of America’s atomic weapons – Glenn Seaborg, Edwin McMillan, Robert Oppenheimer, John Lawrence, and Edward Teller.

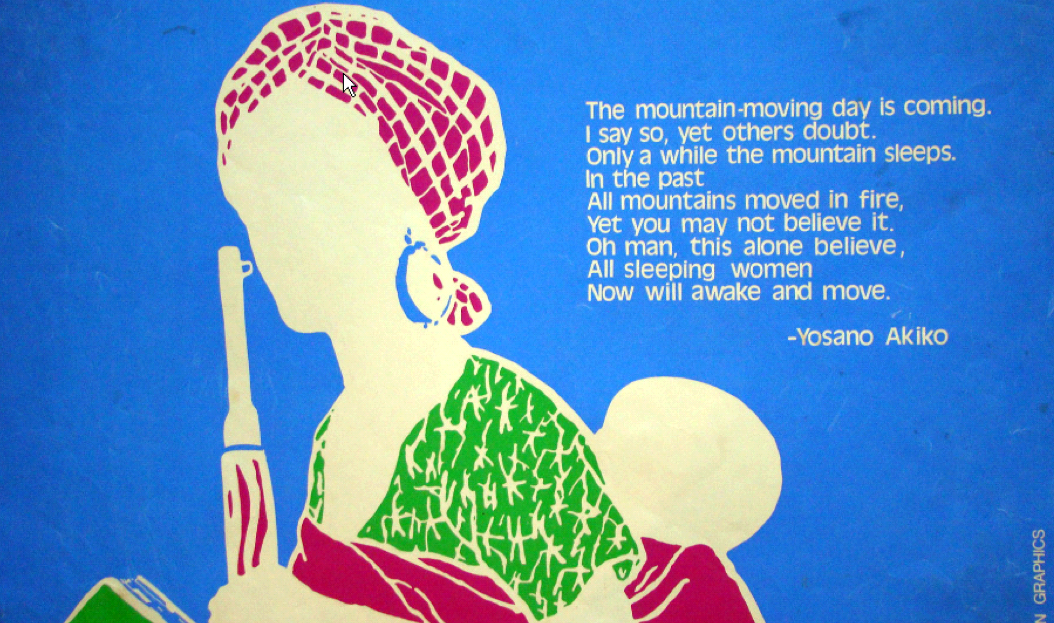

This 1972 poster was produced by the Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective. Online we learn: “The Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective was organized in 1970 to create posters for the growing women’s liberation movement. The Women’s Graphics Collective used silkscreen to create large brilliantly colored prints in large quantities on a low budget. Later the group used offset printing for the more popular posters. The founders of the Graphics Collective wanted their new feminist art to be a collective process in order to set it apart from the male-dominated Western art culture. Each poster was created by a committee of 2 to 4 women led by the artist/designer. Thousands of posters were sold all over the world until the Graphics Collective dissolved in 1983.”

The words are those of Japanese poet Yosano Akiko. In September 1911, her poem, “Mountain Moving Day,” was published on the first page of the first edition of Seito, a magazine that marked the beginning of the Seitosha movement. The women of Seito used literary expression to fight Confucian-based thought and improve opportunities for women.

In a nutshell – pure feminist artistic expression.

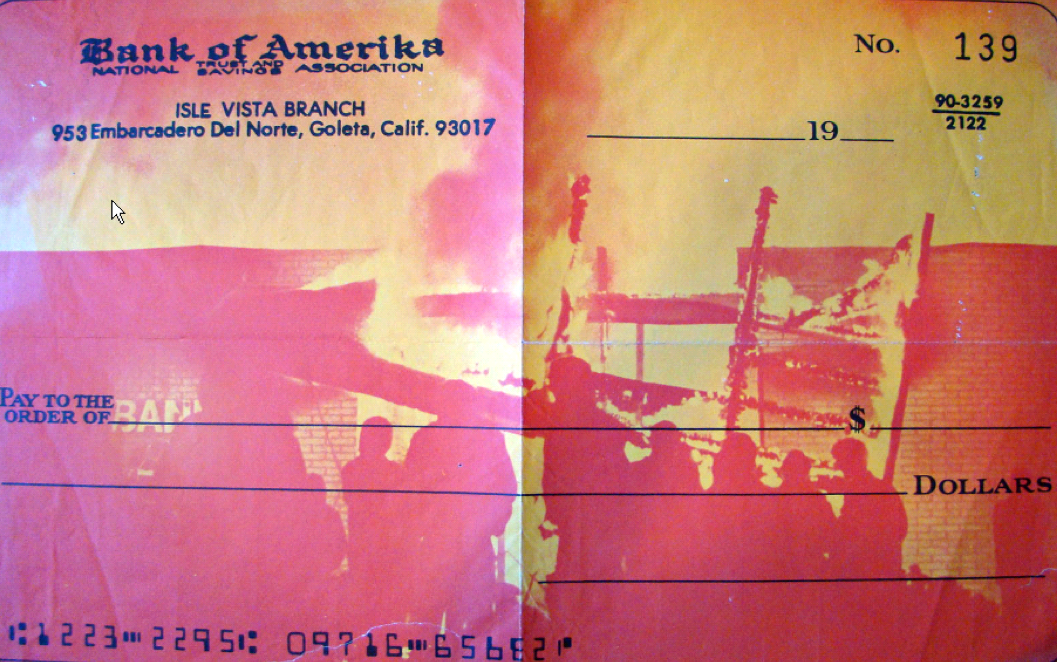

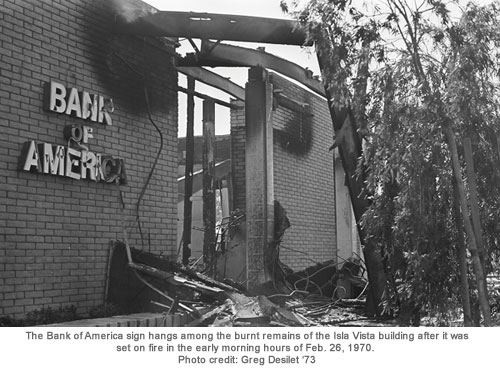

We think of Santa Barbara as staid and Republican, and of UC Santa Barbara as quiet and party-friendly. On February 25, 1970, shit got real in Isla Vista, UC Santa Barbara-adjacent. Students/protestors ran pushed police of town and burned the local branch of the Bank of America at 935 Embarcadero Del Norte. Issues at play in Santa Barbara at the time were the April 1969 Union Oil Spill, the firing of popular assistant professor Bill Allen of the Anthropology Department, and growing opposition to the Vietnam War.

It was seen through the young/new left as a glorious blow against the empire. In 1979, retired FBI agent Crillon C. Payne II wrote in Deep Cover that FBI agents embedded in the student community in Santa Barbara had acted as agents provocateurs and incited the bank burning, a classic Counter Intelligence Program action. Who knows. The Bank of America branch on Telegraph was modified in the spirit of a fortress, perhaps because of Isla Vista.

The Tribe paid attention to what happened in Isla Vista.

For more – read this or buy this.

The poster is one of the more striking visuals of the era. If the Crill Payne COINTELPRO angle is true, it is all more emblematic.

I have found nothing about this particular poster. The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China produced thousands of powerful social and political posters to exhort the Chinese people in the sweeping transformation of Chinese society. From 1966 to 1976, there was a countrywide mass campaign to reform Chinese society and the Communist Party, directed by Mao Zedong, that resulted in mass social upheaval. Those who were not considered to be following the right socialist path were called out as class traitors, some sent to re-education labor camps. Everything and everyone was meant to serve the greater effort of the socialist revolution. The Chinese posters were bright, powerful, and uniformly utopian in their portrayal of the ideal society.

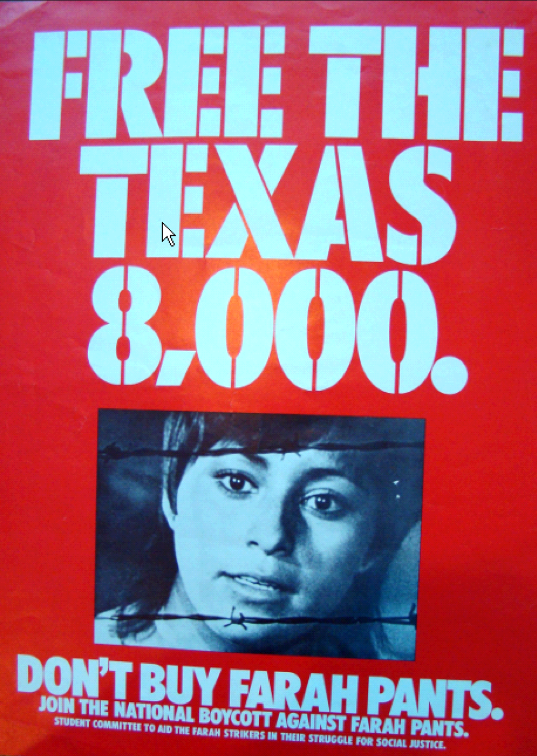

From the Texas State Historical Association: “In May 1972, 4,000 garment workers at Farah Manufacturing Company in El Paso went out on strike for the right to be represented by a union. The strikers were virtually all Hispanic; 85 percent were women. Their labor action, which lasted until they won union representation in March 1974, grew to encompass a national boycott of Farah pants. Before the strike Farah was the second largest employer in El Paso. Low wages, minimal benefits, pressure to meet high production quotas, and tensions between workers and supervisors produced a dissatisfied work force.

“In 1969 male workers from the cutting room voted to affiliate with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. Organizing soon spread to the rest of Farah’s five El Paso plants. When workers at Farah’s San Antonio plant were fired for joining a union-sponsored march in El Paso, more than 500 of them walked out; El Paso workers followed on May 9, 1972. The strike was quickly declared an unfair-labor-practice strike, and a month later a national boycott of Farah products was begun, endorsed by the AFL-CIO. The strike exacerbated ethnic tensions between Anglos and Hispanics, and split the Hispanic community as well. Striking workers were quickly replaced by workers from El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. But union relief funds, the national boycott, and the Catholic Church all provided important sources of support for the strikers. Strikers acquired skills such as public speaking and organizing activities that brought new groups of people together. The company, its sales badly damaged by the national boycott, was ordered by the National Labor Relations Board in January 1974 to offer reinstatement to the strikers and to permit union organizing. In February Willie Farah recognized the ACWA as the bargaining agent for the Farah employees. The 1974 union contract included pay increases, job security and seniority rights, and a grievance procedure.”

Progressive unions and groups like the Vietnam Veterans Against the War supported the Farah boycott. Several members of Red Sun Rising had close ties with the United Farm Workers, and the UFW had a natural affinity with the Farah strike and boycott.

This was a 1972 poster by Cuban graphic artist Rene Menderos in support of the newly launched Venceremos Brigade. Menderos was a brilliant artist whose designs influenced a generation of artists around the world. Here is his obituary.

From the Venceremos Brigade website: “In 1969, a coalition of young people formed the Venceremos (“We Shall Overcome”) Brigade, as a means of showing solidarity with the Cuban Revolution by working side by side with Cuban workers and challenging U.S. policies towards Cuba, including the economic blockade and our government’s ban on travel to the island. The first Brigades participated in sugar harvests and subsequent Brigades have done agricultural and construction work in many parts of the island.”

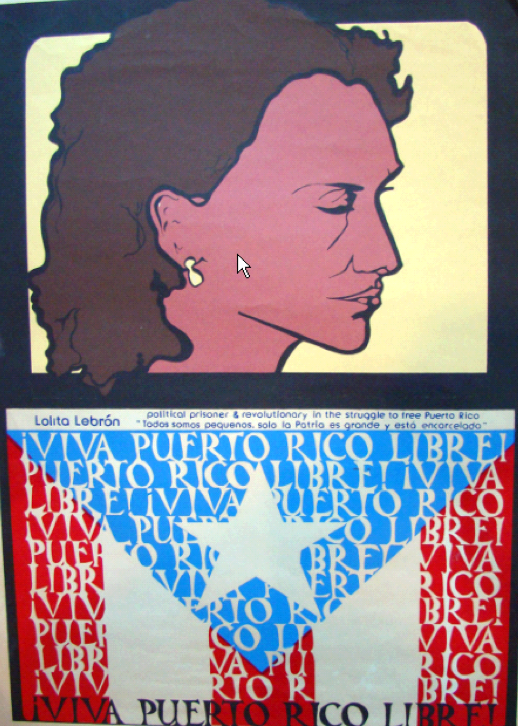

This poster was produced by the La Raza Silkscreen Collective in 1972. It celebrates Puerto Rican nationalism.

In the late 1940s, Puerto Rico was still a colony, and it was illegal to advocate independence, fly the Puerto Rican flag, or sing patriotic songs thanks to Law 53 – the Ley de la Mordaza (the Gag Law). Where nonviolent revolution is impossible, violent revolution is inevitable, and thus it was in Puerto Rico in the 1950s. Nationalists, led by Albizu Campos (1891-1965) and Blanca Canales (1906-1996), planned an armed revolution to start in 1952. Police interventions in October 1950 forced their hand, and so the nationalists launched the October Revolution, which consisted of armed uprisings in about a dozen cities and towns, most prominently the Jayuya Uprising. The nationalists held the town of Jayuya for three days until the United States declared martial law and American bombers and artillery were brought in to crush the rebels, even if meant destroying parts of the town. Rebels who surrendered after the uprising in Utado learned the price of resisting American colonialism. They were marched through the streets, taken behind the police station, and machine-gunned. No trial, no verdict, just a sentence.

As Jayuya fell to American guns, on November 1, 1950, two Puerto Rican nationalists attacked presidential guards stationed outside the Blair House in Washington D.C. where President Truman was living while the White House was being renovated. Truman opened a window of Blair House when he heard the gun battle erupt, but as presidential assassination attempts go this was fairly remote, a gun battle between two nationalists and presidential guards that left one nationalist and one guard, Leslie Coffelt, dead. On March 1, 1954, four Puerto Rican nationalists, including Lolita Lebron (1919-2010), unfurled a Puerto Rican flag from the visitors’ gallery of the House of Representatives and began shooting randomly to the floor below. Five Congressmen were injured and all four attackers were arrested. A note in the Lebron’s purse read in part: “The United States of America is betraying the sacred principles of mankind in their continuous subjugation of my country.”

The shooters spent 25 years in prison until being pardoned by President Carter.

The caption of this Chinese poster read “U.S. Imperialism Get Out of South Vietnam.” There were gradations within the opposition to the war in Vietnam. From center to left – peace movement, anti-war movement, anti-imperialism movement. The Left in large part embraced Ho Chi Minh, North Vietnam, and the Vietcong as the heroes of the war in Vietnam. The portrayal of Vietnamese fighters as heroic, firm, and determined was a steady theme.

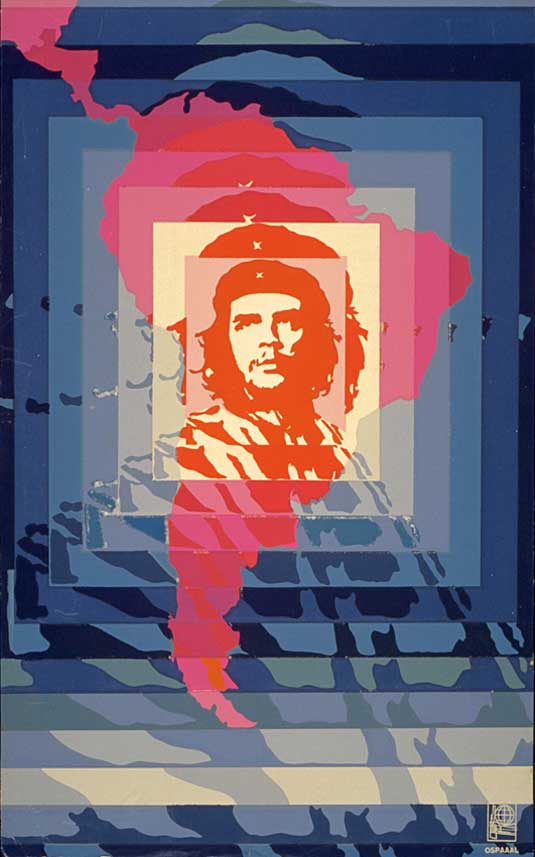

Ernesto “Che” Guevara was a major figure in the Cuban revolution. He was executed by CIA-led Bolivian Army troops in Bolivia on October 9, 1967. His image was a ubiquitous symbol of revolution for the counterculture of the 1960s. I haven’t tracked down this poster. There were many.

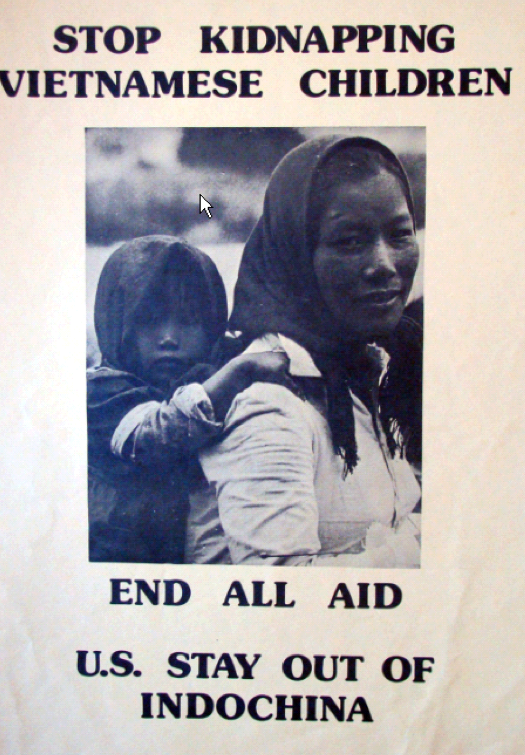

Operation Babylift was a program in the the closing days of the Vietnam when more than 3000 babies were airlifted from Saigon orphanages and delivered to adoptive families in the US, Canada, Britain, Europe and Australia.

It was the largest mass adoption in history. The recently victorious nationalist Vietnamese government considered it a politically-motivated act of kidnapping.

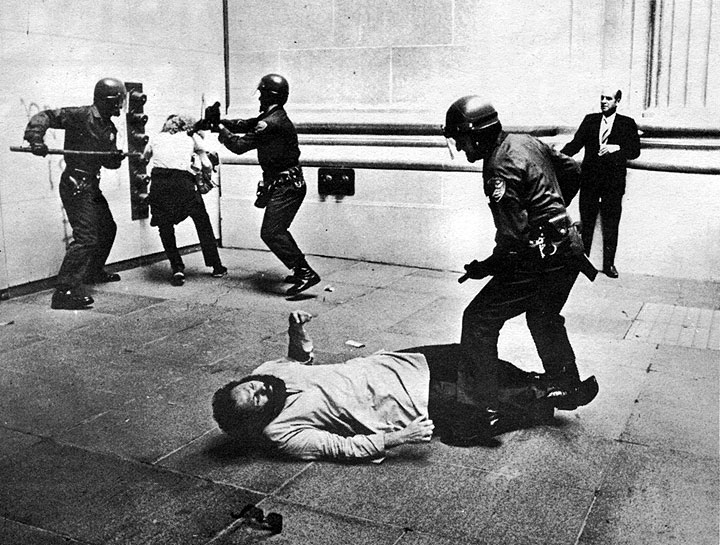

No words needed. The police were the enemy. Everywhere. The image here is of Oakland police at the 1967 Oakland Army Terminal demonstrations. The demonstration turned into something of a battle.

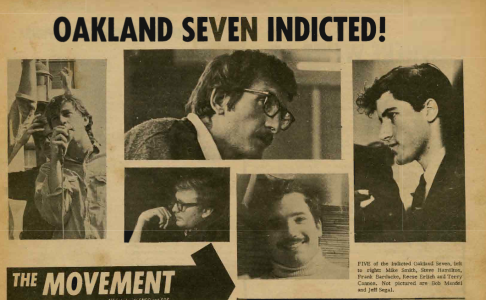

Seven demonstrators were indicted for their actions – Mike Smith, Steve Hamilton, Frank Bardacke, Reese Erlich, Terry Cannon, Bob Mandel, and Jeff Segal. They were acquitted.

Seize the Time : The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton by Bobby Seale was first released in 1970. The San Francisco Mime Troupe also produced a play based on this book in 1970. He was indicted as part of the Chicago Eight conspiracy. He did not go quietly.

Seize the Time : The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton by Bobby Seale was first released in 1970. The San Francisco Mime Troupe also produced a play based on this book in 1970. He was indicted as part of the Chicago Eight conspiracy. He did not go quietly.

Although there was precious little evidence of conspiracy against him, if any, Judge Hoffman sentenced Seale to four years in prison for contempt. That, my friend, is a lot of contempt. After prison, Seale ran for mayor of Oakland and finished second in a field of nine. He left the Panthers in 1974 and has since then lead a life of exemplary radical community organizing. His website – here.

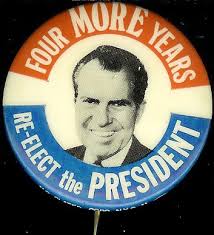

A funny thing happened on the way to the Republican Convention in San Diego. They moved it to Miami only three months before the convention. Evidence surfaced of ITT offering to donate $400,000 (which then was big bucks) to the San Diego convention in return for favorable disposition of a problem with the Justice Department.

So they moved to Miami. What a convention! The first of the entirely scripted conventions. We remember: (1) chants by Young Americans for Freedom of “Four More Years!”

(2) Vietnam vets in the streets. Some in wheelchairs.

Here is a little of what Hunter Thompson wrote about them: “The Vets made their camp in a far corner of the Park, then sealed it off with a network of perimeter guards and checkpoints that made it virtually impossible to enter that area unless you knew somebody inside. There was an ominous sense of dignity about everything the VVAW did in Miami. They rarely even hinted at violence, but their very presence was menacing-on a level that the Yippies, Zippies, and SDS street crazies never even approached, despite all their yelling and trashing.” As always, Hunter nailed it.

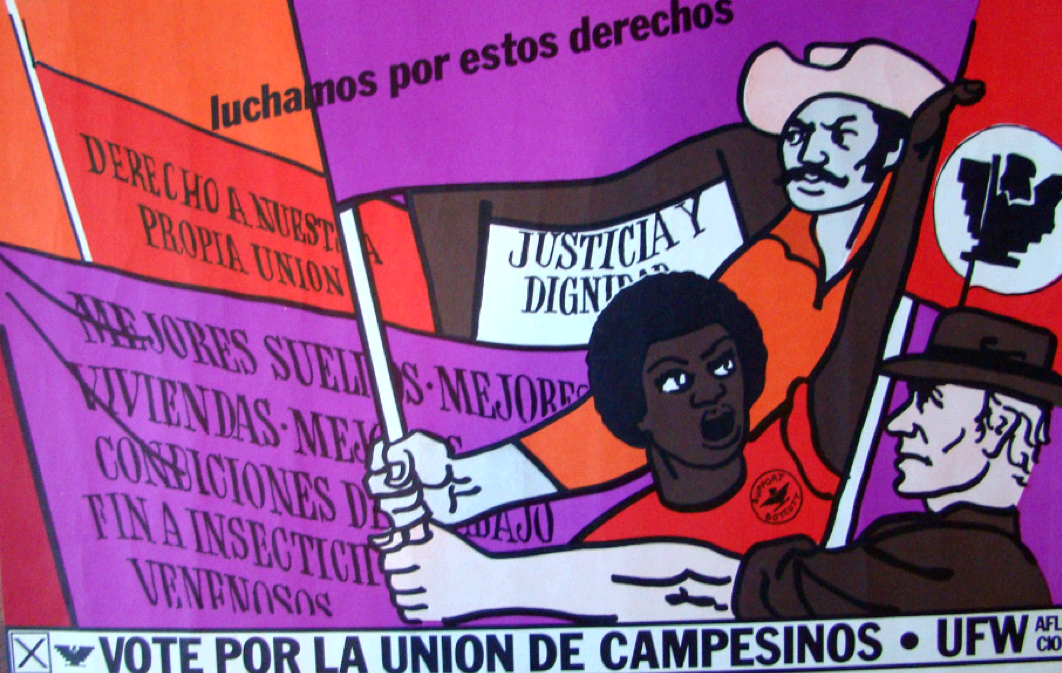

This one I know about. From the beginning of the grape strike in 1965 until 1975, the United Farm Workers fought for recognition and contracts without the benefit of any labor law, state or national. For reasons that have everything to do with class and race, farm workers are excluded from the National Labor Relations Act. Strikes and boycotts, not government-sponsored elections, got recognition and contracts.

In 1975, the California legislature passed the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which provided for secret ballot elections for farm workers wanting union representation. For the first time in its existence, the UFW now had to turn to massive, traditional organizing. The International Brotherhood of Teamsters was the union favored by employers, and so it was a two-front war.

This poster was created and printed, if I am remembering correctly, in Chicago through by a graphics collective with ties to the UFW boycott. It reads “We struggle for these rights … right to our own union … better wages … better working conditions … an end to poisonous pesticides …. Vote for the Farm Workers Union.”

Two members of Red Sun Rising had shifted gears from the revolutionary politics of Berkeley to the pragmatic realpolitik of the UFW fight. In 1975, they worked on UFW organizing campaigns in Livingston and Delano. And sent this poster to their friends in Berkeley.

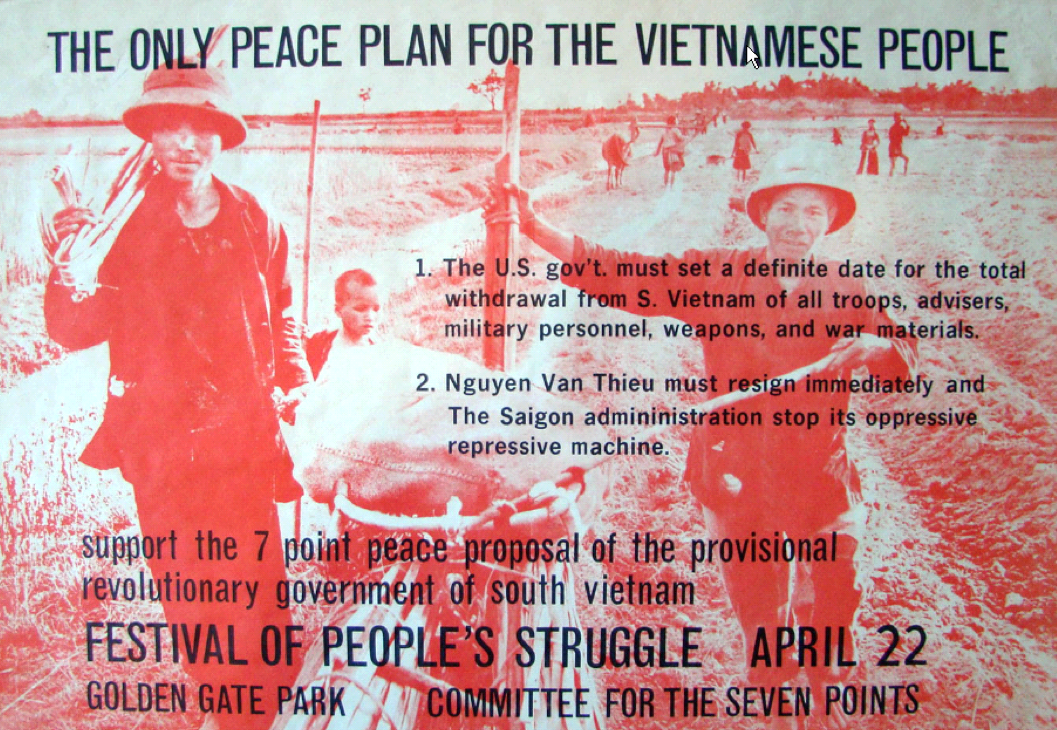

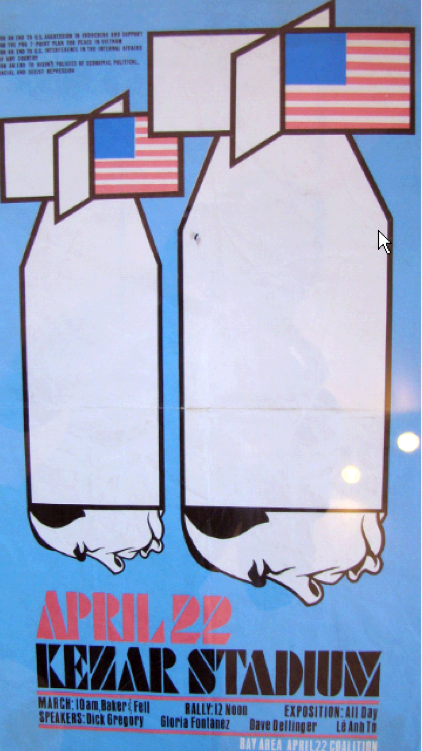

This 1972 poster urges support for the Peace Proposal of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Viet Nam, July 1, 1971. It interests me that the group – the Bay Area April 22nd Coalition 2409 Telegraph Ave – does not advocate support for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam Peace Proposal of June 26, 1971. Who wants to compare and contrast the two proposals and report back?

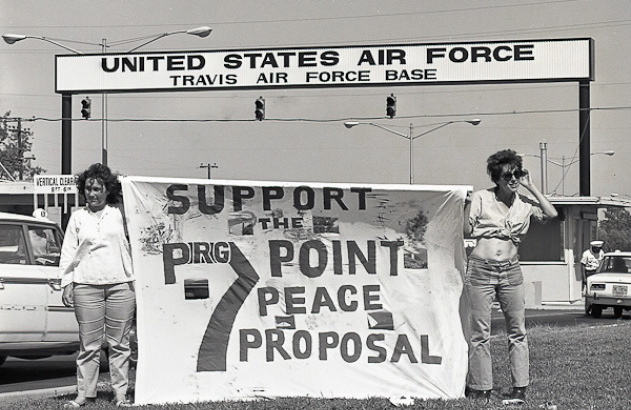

I don’t find out much about the actual demonstration although I did find this photo of an August 26, 1972 demonstration at Travis Air Force Base supporting the 7 Point Plan.

Here is what I have found out about this 1972 poster: nothing. Nada. Zilch. Still trying. But as of now: nothing.

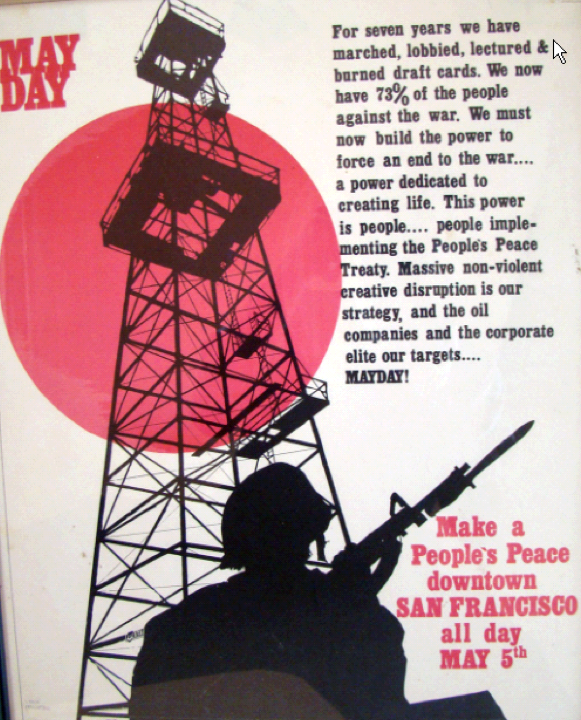

This one I found. An article in the May 7, 1971 edition of Good Times tells the story. It was not a huge demonstration. But it got rough.

The police usually came out on top when it came to force. They did here. Not a pretty sight at all.

What a perfect villain Sprio Agnew was! I know the demands made by the Committee for Just Rewards. They will sound familiar: (1) U.S. acceptance of the 7-point peace plan of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South View for Peace in Indochina; (2) an end to U.S. political, economic, and military oppression of foreign – particularly third world – nations; and (3) an end to the Nixon Administration’s domestic policies of political, economic, and racial oppression. All those who opposed the repressive politics of the Nixon Administration were invited to join the demonstration.

I am told that the demonstration turned into a riot after a protestor pulled the fire alarm in the hotel where Agenw was speaking. The sprinklers deployed, and the wealthy Republican donors came running outside, wet and confused.

The rally advertised in this poster took place in 1972.

The Chronicle‘s coverage of the rally conceded that 25,000 to 30,000 attended, but it harped on the absence of liberals. Robert Scheer, a good friend of Red Sun Rising, was a speaker at the rally. He led a chant of “Support the Seven Points!” The Seven Points sure got a lot of play. I remember none of it. Shame on me. Dick Gregory spoke, as advertised, and announced that he was starting a 40-day fast.

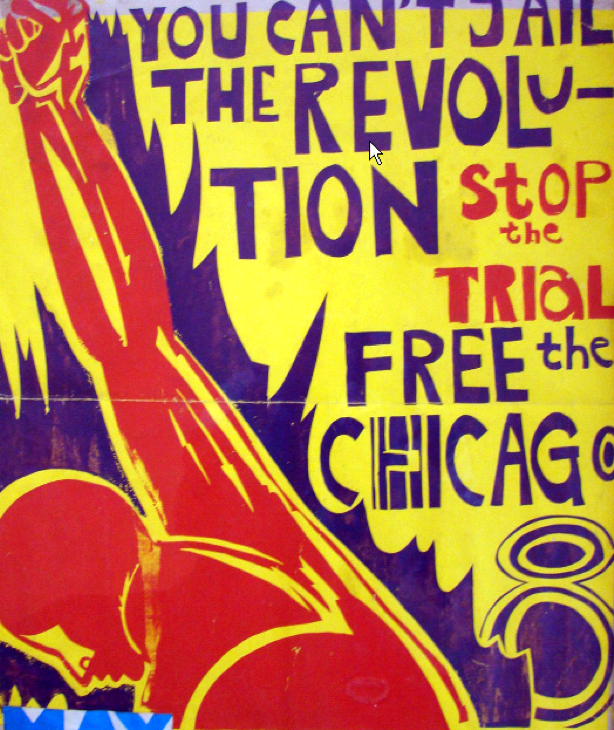

This 1969 poster screams defiance in the wake of conspiracy charges being filed against eight men involved in the riots at the Democratic convention in Chicago in August 1968.

The Chicago 8 became the Chicago 7 shortly after the trial started when Judge Hoffman decided he couldn’t deal with Black Panther Bobby Seale. What a mess. Ridiculous charges. Guerilla theater in the courtroom. A judge with an absolute lack of judicial temperament handing out contempt citations like they were Christmas presents. Acquittals on the most serious charges, some minor convictions, lots of contempt. Everything overturned on appeal. The Old Order vs. the New Order. The trial lasted from October 1969 until February 1970. What a mess. It radicalized many.

The Oakland Museum dates this poster as circa 1980, meaning it may be from the collection of a Red Sun Rising member but not from Red Sun Rising days. Jerry Biggs is identified as the artist. Malcolm and Ho were iconic revolutionary leaders lauded by the left.

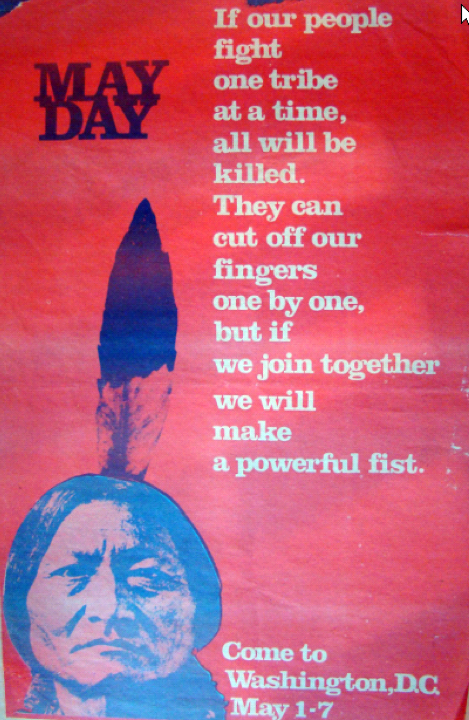

The words are those of Chief Little Turtle of the Miami tribe. He was also known as Michikinikwa, Meshekunnoghquoh, Michikinakoua, Michikiniqua, Me-She-Kin-No, Meshecunnaquan and Mischecanocquah

The words are those of Chief Little Turtle of the Miami tribe. He was also known as Michikinikwa, Meshekunnoghquoh, Michikinakoua, Michikiniqua, Me-She-Kin-No, Meshecunnaquan and Mischecanocquah

The event is one that I know about. I was there. I got arrested. Along with 12,000 other people. I wasn’t going to go but the boyfriend of one of the nurses who lived upstairs from us on Baltimore Avenue was in the service and he urged us to go. I hitched down from Philadelphia, finding my way to Georgetown University where I spent the night. Federal troops were everywhere. It was not a good feeling. I was arrested after only a few minutes downtown, before my group could commit civil disobedience.

A police bus took us underground somewhere, down on a bus elevator. I didn’t enjoy my day in a holding pen. We were released at dinnertime. Hitching back to Philadelphia I never waited more than a few minutes for a ride. People knew who I was, or where I had been. Opposition to the war seemed pretty universal. I went for dinner at a dive near the jail. They gave me free dinner. The Inquirer came and interviewed me. They ran my picture in the story. I will scan it soon and add it here.

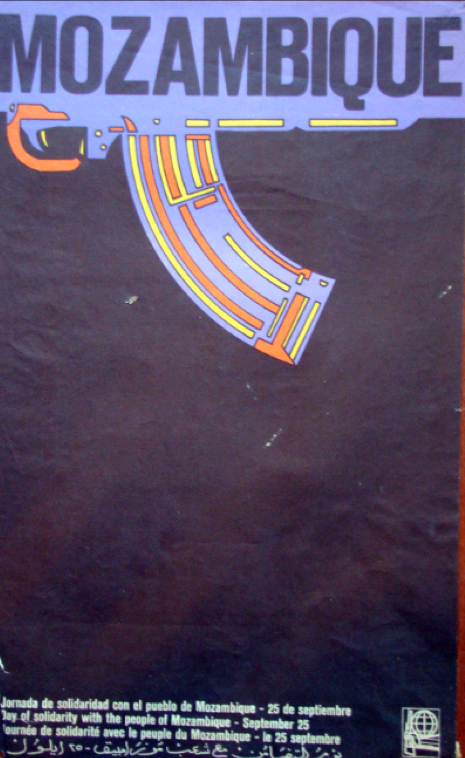

This 1971 poster celebrated solidarity with the people of Mozambique. At the time of the poster, Mozambique was a colony of Portugal. The government of Portugal was anti-commnist, anti-socialist, anti-liberal, and staunchly Roman Catholic. The regime, known as Estado Novo, fought hard to retain Portugal’s huge colonial empire.

This 1971 poster celebrated solidarity with the people of Mozambique. At the time of the poster, Mozambique was a colony of Portugal. The government of Portugal was anti-commnist, anti-socialist, anti-liberal, and staunchly Roman Catholic. The regime, known as Estado Novo, fought hard to retain Portugal’s huge colonial empire.

As other European powers ceded their control over former colonies, Portugal held on. There emerged in Africa liberation movements – in Angola, in Portuguese Guinea, and in Mozambique. Collectively this was known as the Portuguese Colonial War (if you lived outside Portugal in the development world), the Overseas War (if you lived in Portugal), and the War of Liberation (if you lived in Africa). Again, the naming is a litmus test.

In Mozambique, the independence/liberation effort was led by the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique, initials FRELIMO, English translation the Mozambique Liberation Front. The movement in Angola attracted the most attention in the United States, but we were aware of the struggle in Mozambique.

P.S. It didn’t end well. Liberation was achieved in 1975 after a bloodless coup in Portugal by leftist military officers. The flight of the governing class after liberation was quickly compounded by 16 years of “civil war,” which consisted equal parts of (1) proxy war between the United States and the Soviet Union; (2) destabilization efforts by the white government of Rhodesia; and (4) destabilization efforts by the white government of South Africa. It did not turn out so well for Mozambique. I was in Maputo in 2006. The effects of colonialism and the Cold War and white racist neighboring regimes could hardly be more evident.

And so, for the time being we have come to the end of our show.

There is always the chance of more of the Red Sun Rising posters turning up, but for now – that’s all folks.

It took a while to go through all these photos with my friend. You know that because you’ve been through them by now. I asked him what he thought, especially all the different struggles depicted in the posters. He took off in a different direction: “They say we won, that we ruined everything that was good. We say that they won, that they crushed everything good that we were trying.” I asked him what Bob Dylan would say. He knew where I was going. “You are right from your side, and I’ll be right from mine.” We then debated the best version of “One Too Many Mornings.” He favors Johnny Cash singing with Dylan. While I greatly enjoy watching the two of them playing and singing together from the Nashville Skyline sessions, for this song I favor Jerry Jeff Walker. We saw him a few times at the Main Point in the 1960s.

But I digress. I brought him back to the subject at hand. What did he think of all the posters from Red Sun Rising?

P.S. After publishing this post, I got an e-mail that said “These are great. But what we really want to see is what posters you had in the 1970s. Can you shed some light on this?

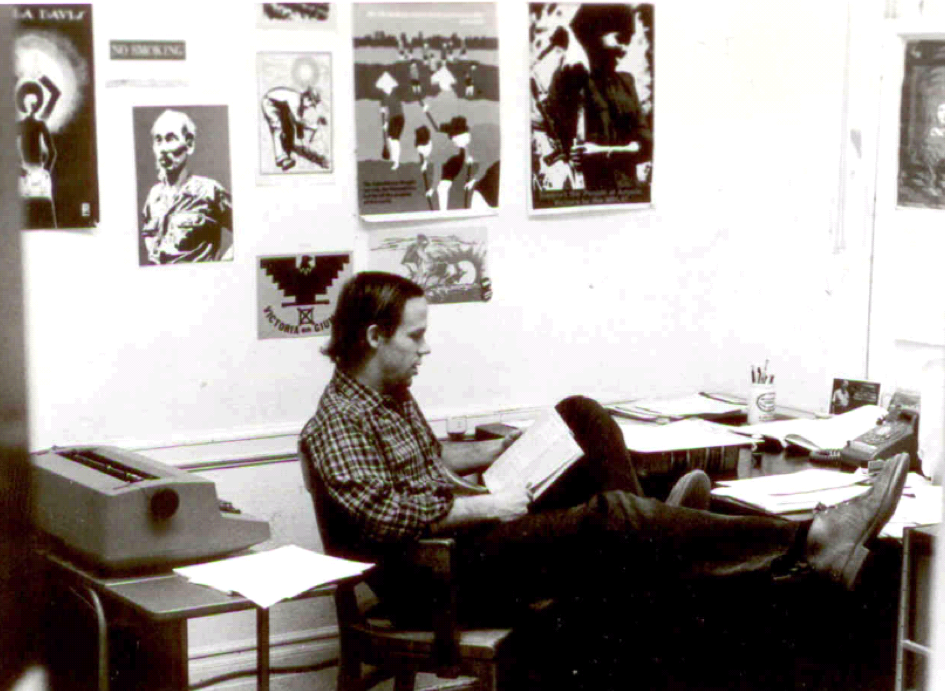

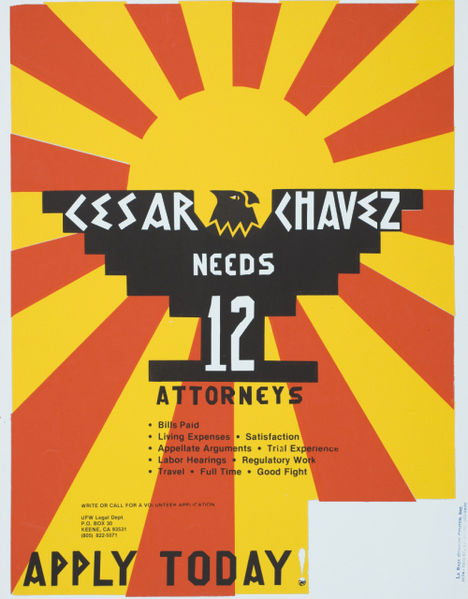

Well, it just so happens that I can. Kirsten Zerger took photos of the UFW legal department office in Salinas shortly before the Night of the Long Knives when Cesar fired all 18 of us lawyers and that many legal workers too for the first time.

There I was, 27 years old, doing what I loved and what I thought I’d do for the rest of my life. But that changed.

Lincoln Cushing has taken photos of almost every poster that I carried with me for decades, seen here.

In this photo, I see three farm worker posters. Left to right then, leaving aside the farm worker posters: Angela Davis, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnamese peasants, Movement for the Popular Liberation of Angola, and Che. You can’t see Che very well. This was the Che poster:

It was a stunning Cuban poster. Helena Serrano designed it to mark the Day of the Heroic Guerrilla in 1968.

These posters are far more political (political = left in the lexicon of the time) than I was. The closest I got to Marx was reading Marx para principiantes (Marx for Beginners) by Rius and that was to work on my Spanish and because I liked his comics Los Agachoados and Los Supermachos. I bought them when I went to Mexicali for a few years.

Nice to see the posters after these years though, 35 years at this writing.

Here is one poster that I did not have.

Shortly after the photo of me above, Cesar fired all 18 of us lawyers. It wasn’t necessarily personal. We were caught up in a series of purges that swept – and destroyed – the Union. He fired us and then had to find some new lawyers. Thus this poster. In the bottom right there was a tear-off pad that you could use to apply for a job.

I can think of six lawyers he hired, maybe one or two more. One of us stayed under the conditions established by Cesar. Inside a couple years they had lost two multi-million-dollar judgments against the Union. They were all gone before long, two of them eventually disbarred. From our point of view, firing us and using a cool poster to recruit replacements was not a successful experiment.

Hello, I am doing a high school report on the Chicago 7/8, and I am interested in the poster supporting them at the National Democratic Convention. If it is possible, I would like to have a primary source on the image. Thank you!

I’d love to help but don’t have a primary source. Posters were kind of loosey-goosey about images.

Tom