On Monday I will write about David Seabury, a recycling master who collects, sculpts, and plays in rock and roll bands.

Today I write his younger brother John. They come from a gloriously quintessentially Berkeley family. If you’re interested in the family story, read this.

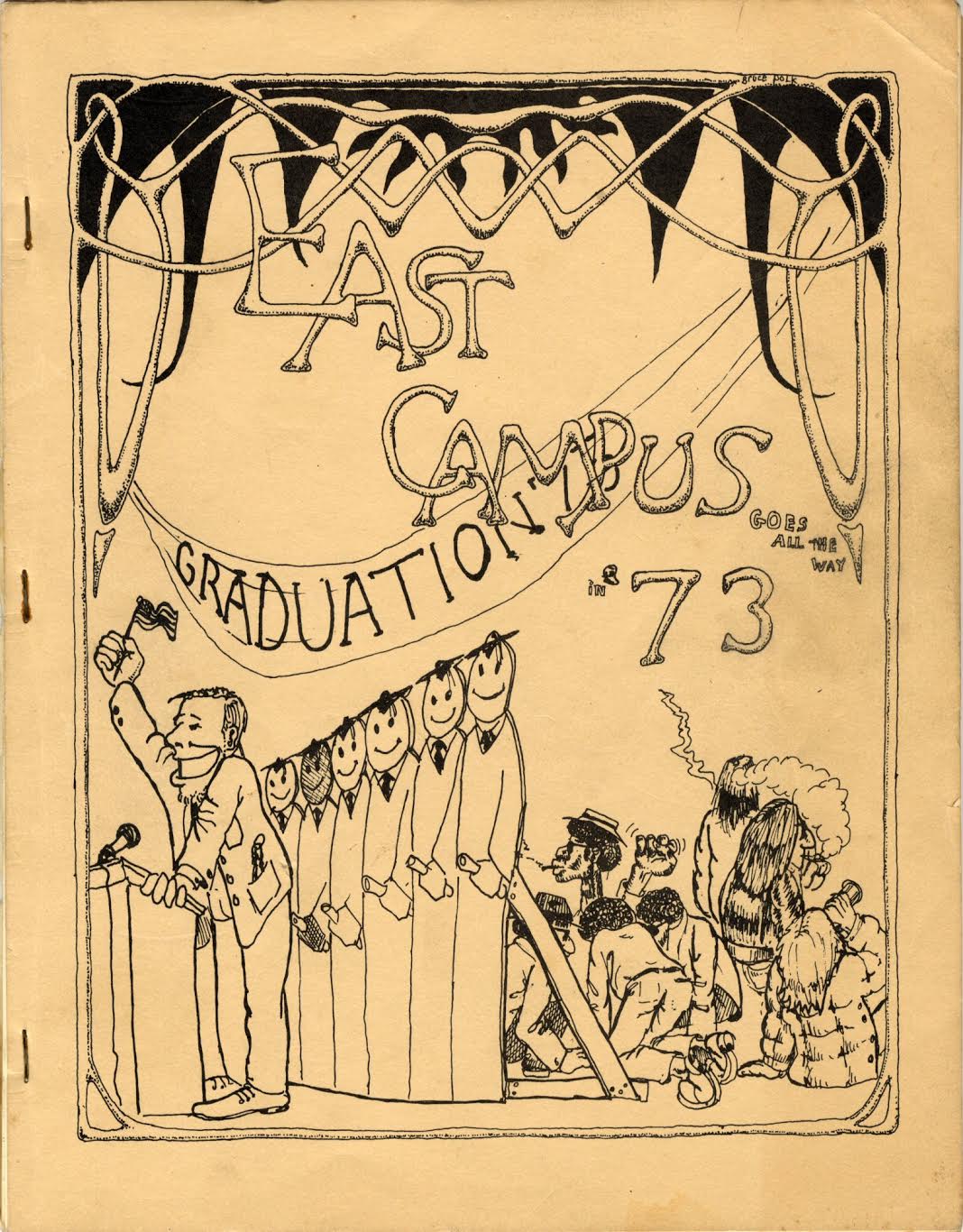

John was a Berkeley High graduate. He finished his high school education at the East Campus, expelled from the main campus for smoking cigarettes on campus.

At the East Campus, he was inspired by an art teacher, Victor Ichioka. Seabury had always been drawn to art. He sketched during his entire childhood, creating Horatio the Hippie as a comic book while in sixth grade. In high school he picked up ceramics and lost-wax (also called “investment casting”, “precision casting”, or cire perdue in French) casting skills. He sold ceramic pot pipes on Telegraph from a booth operated by a friend’s mother. Ichioka made him believe.

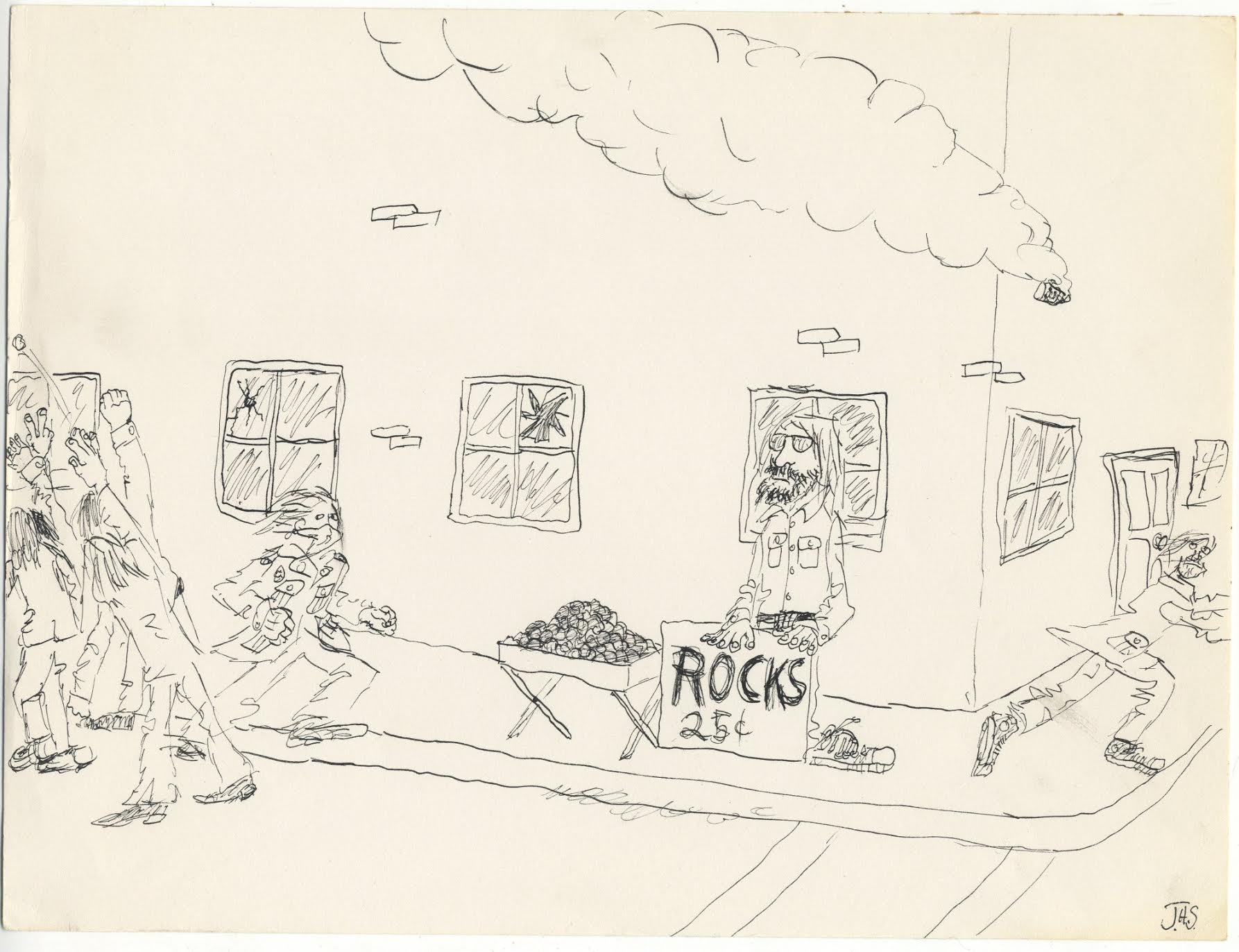

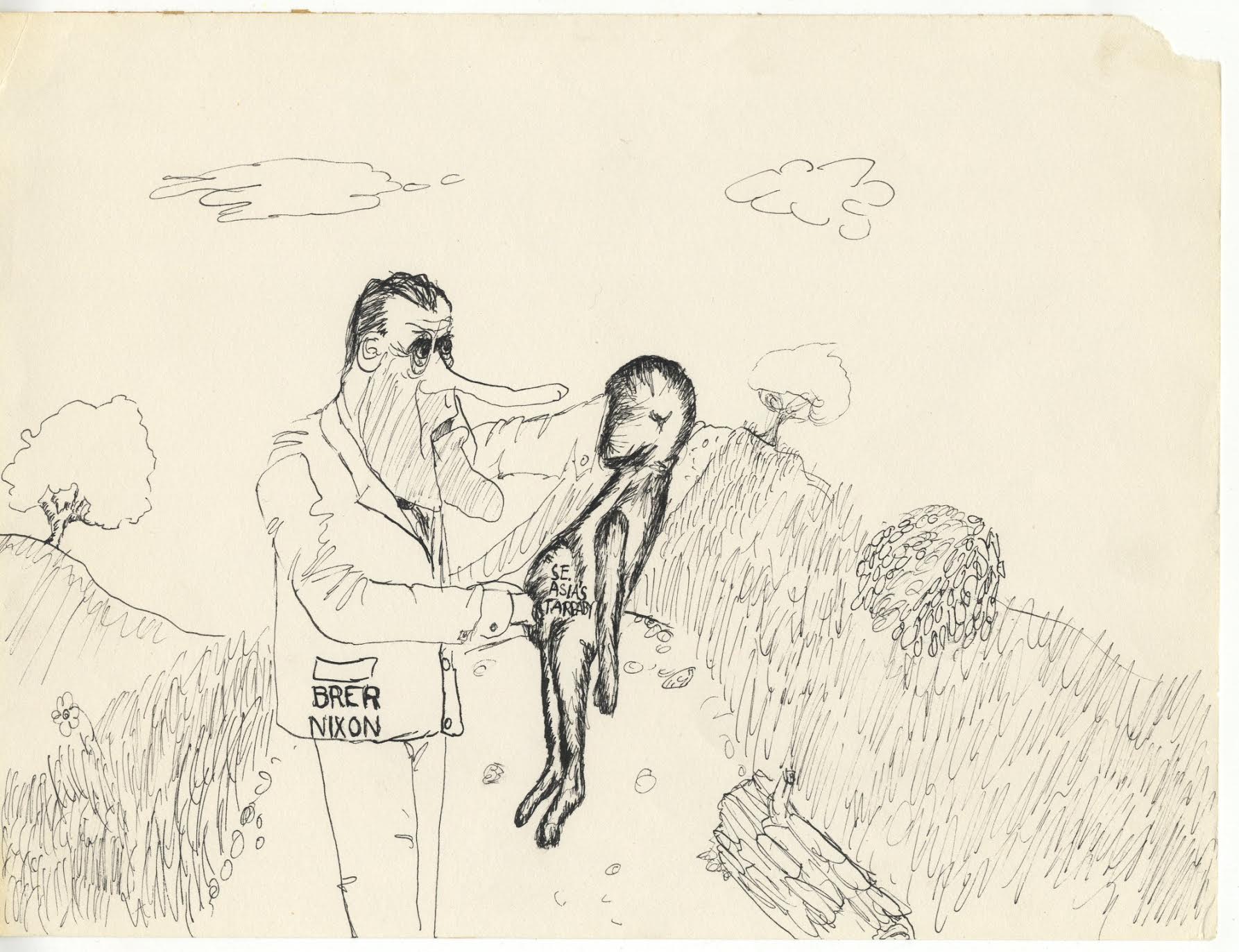

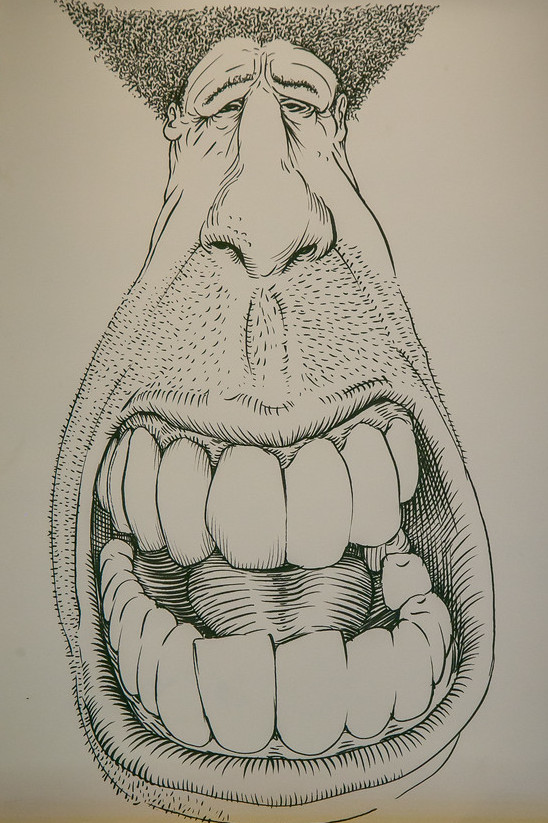

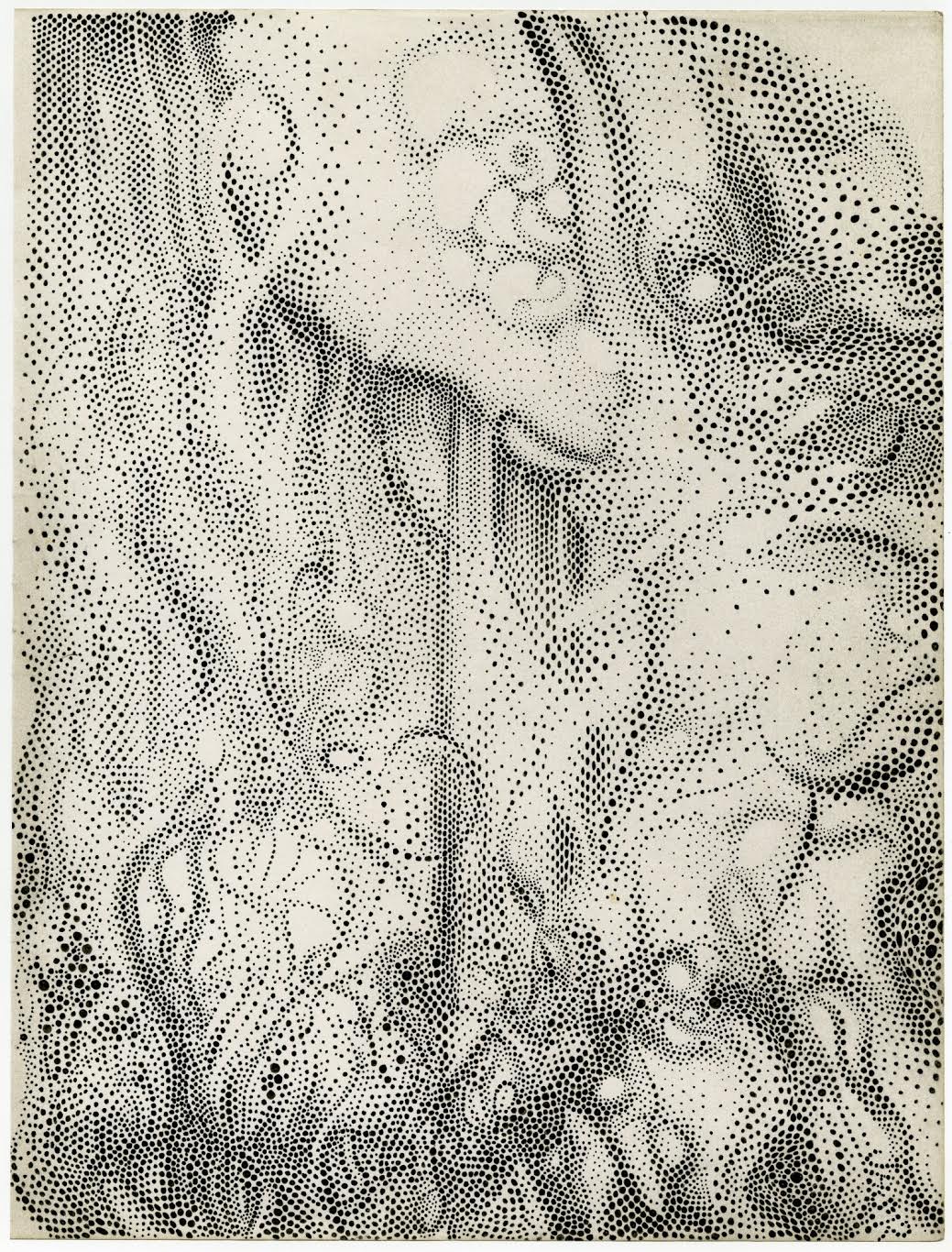

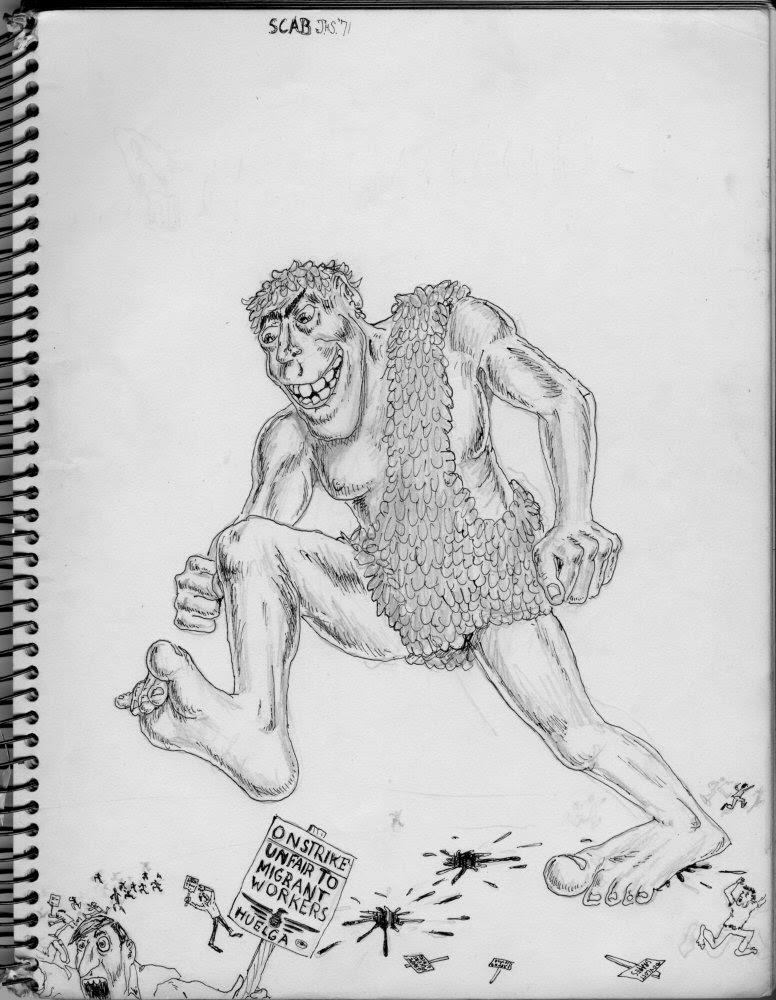

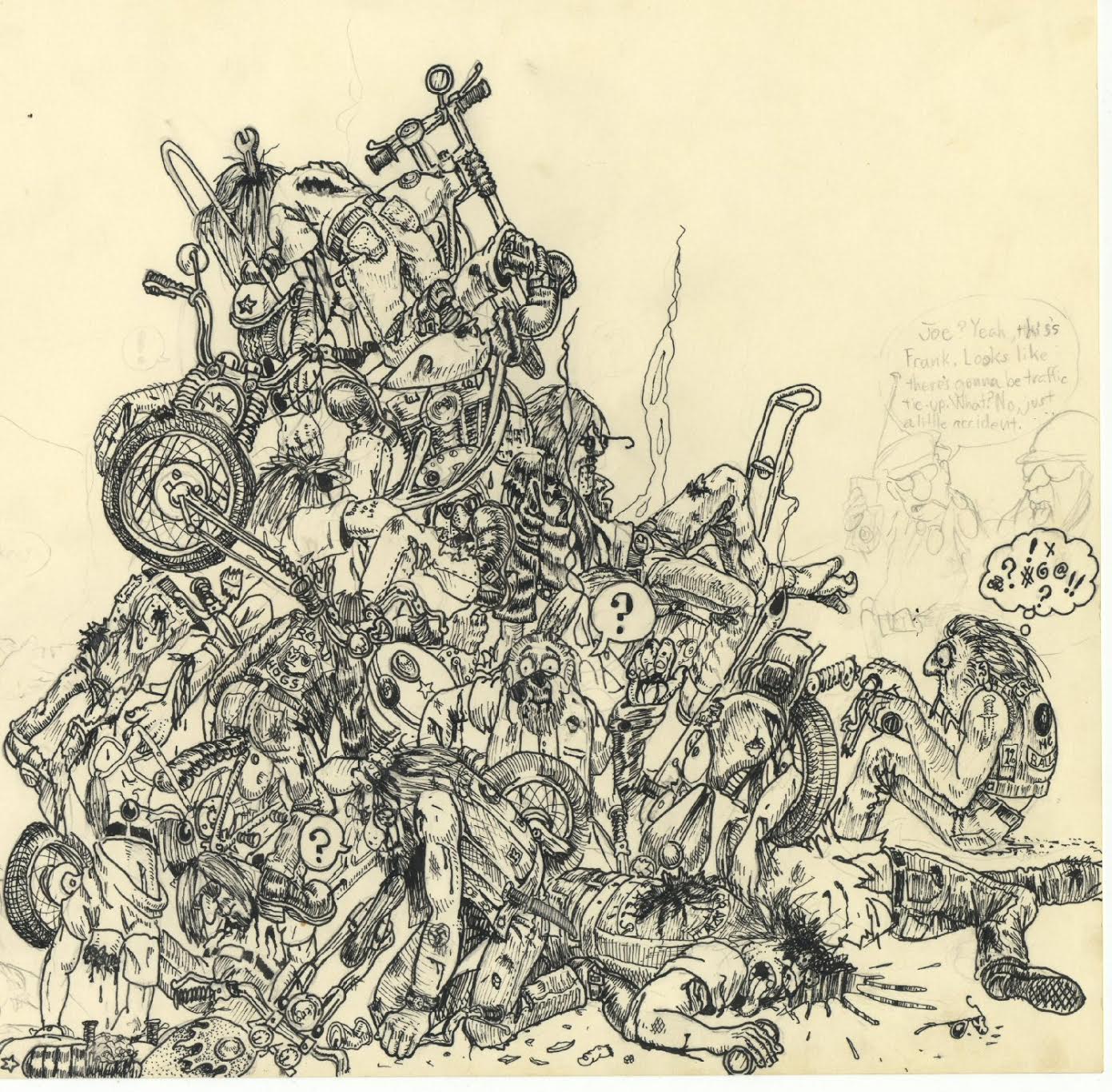

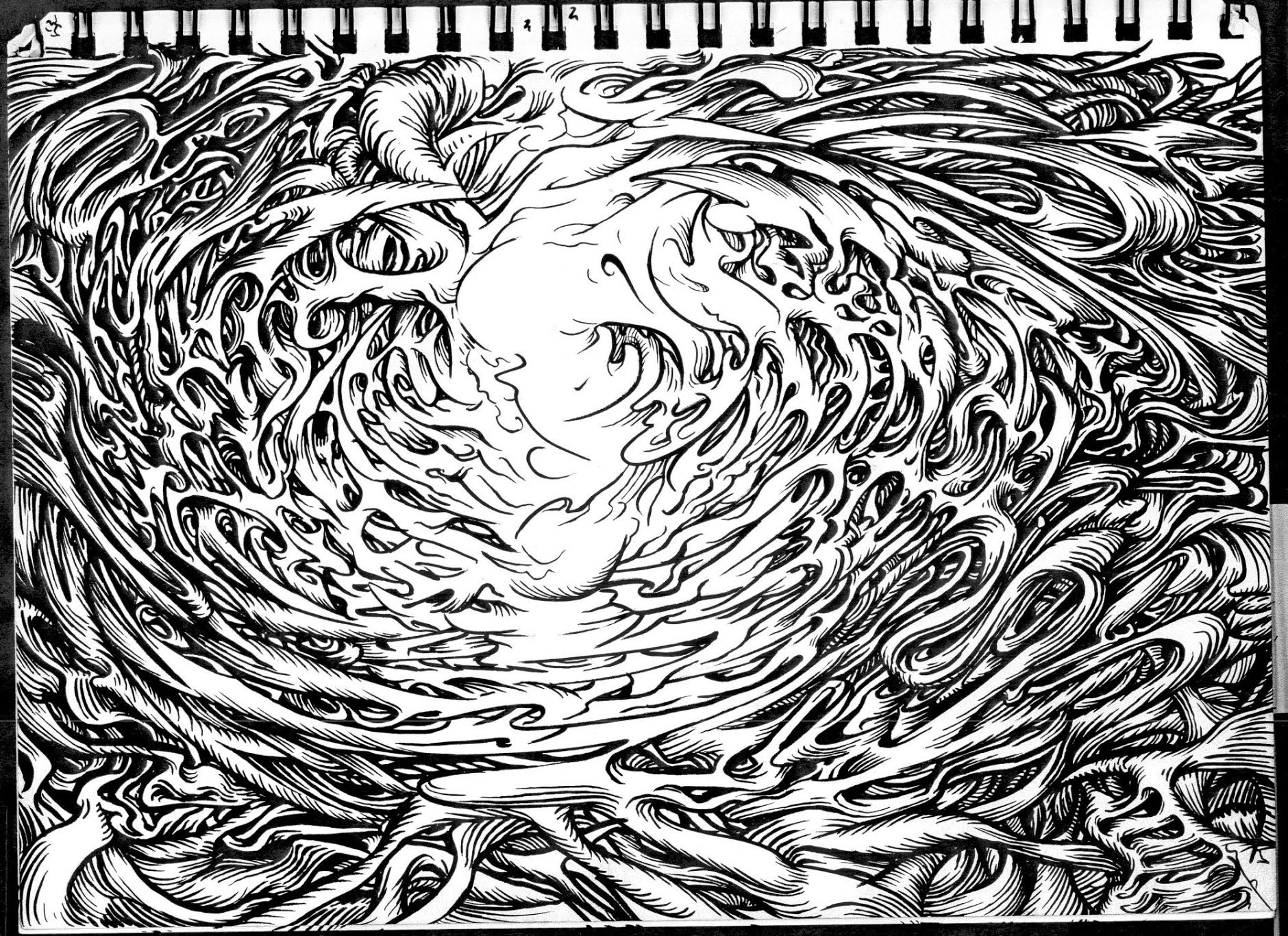

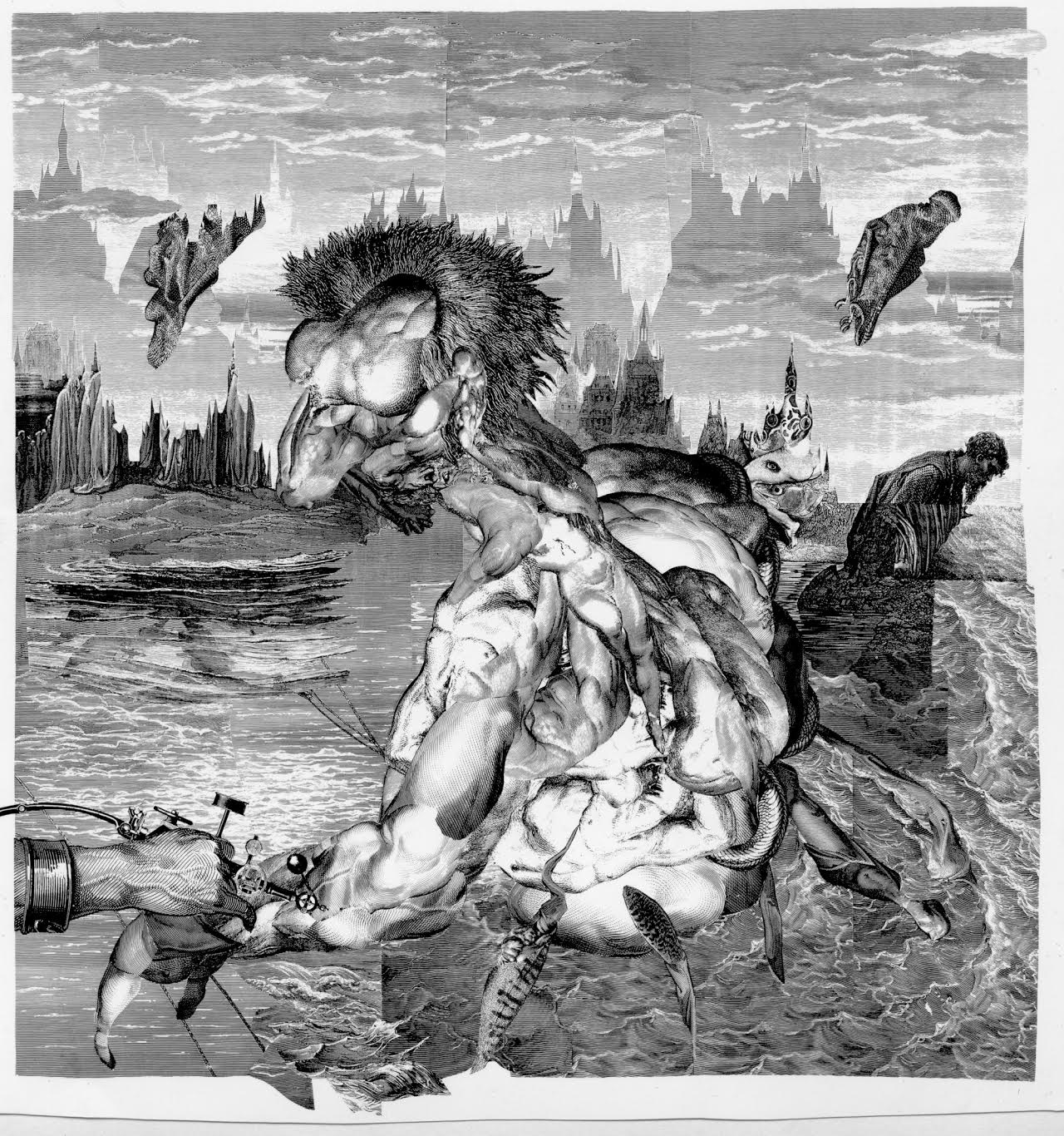

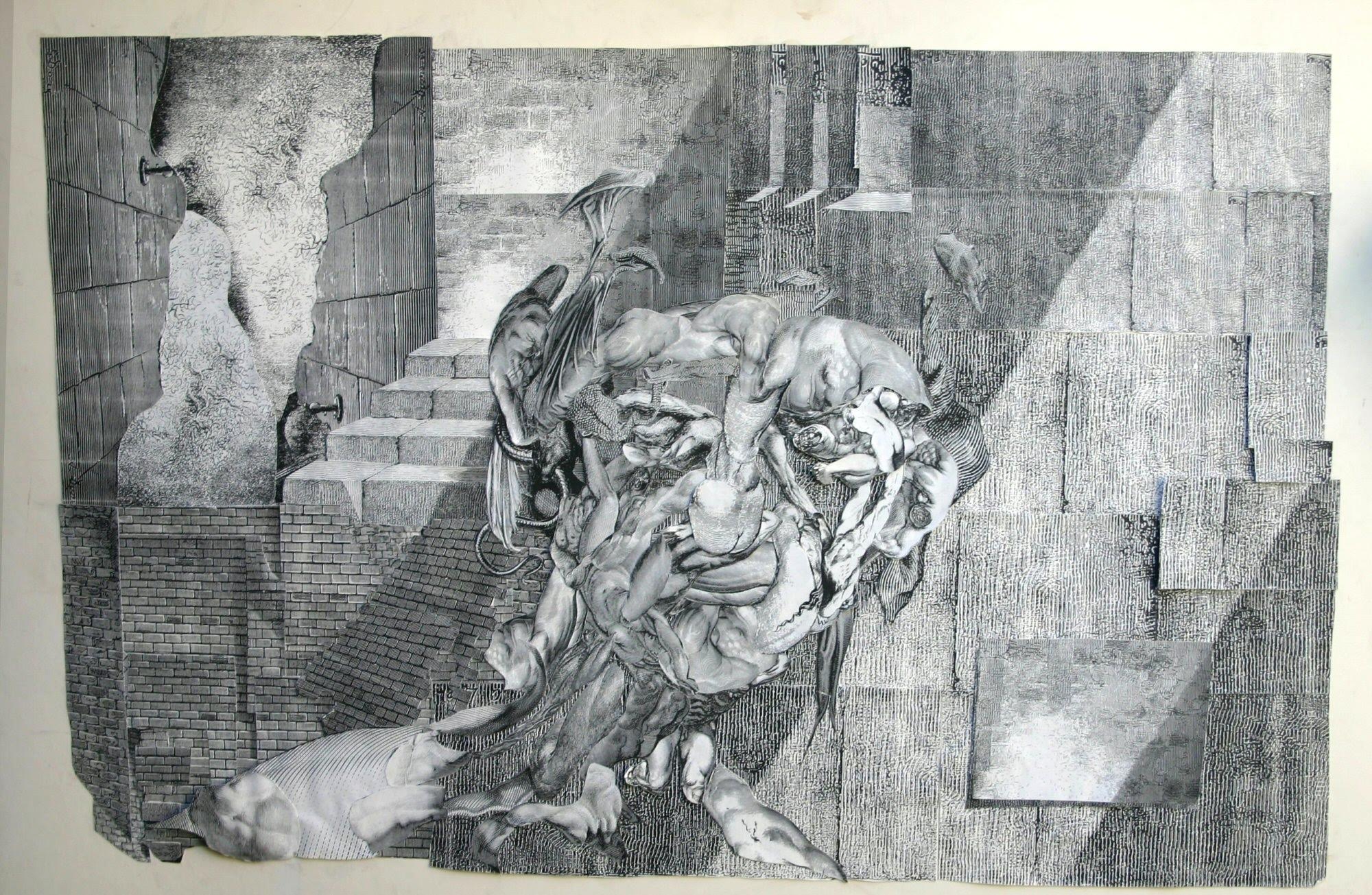

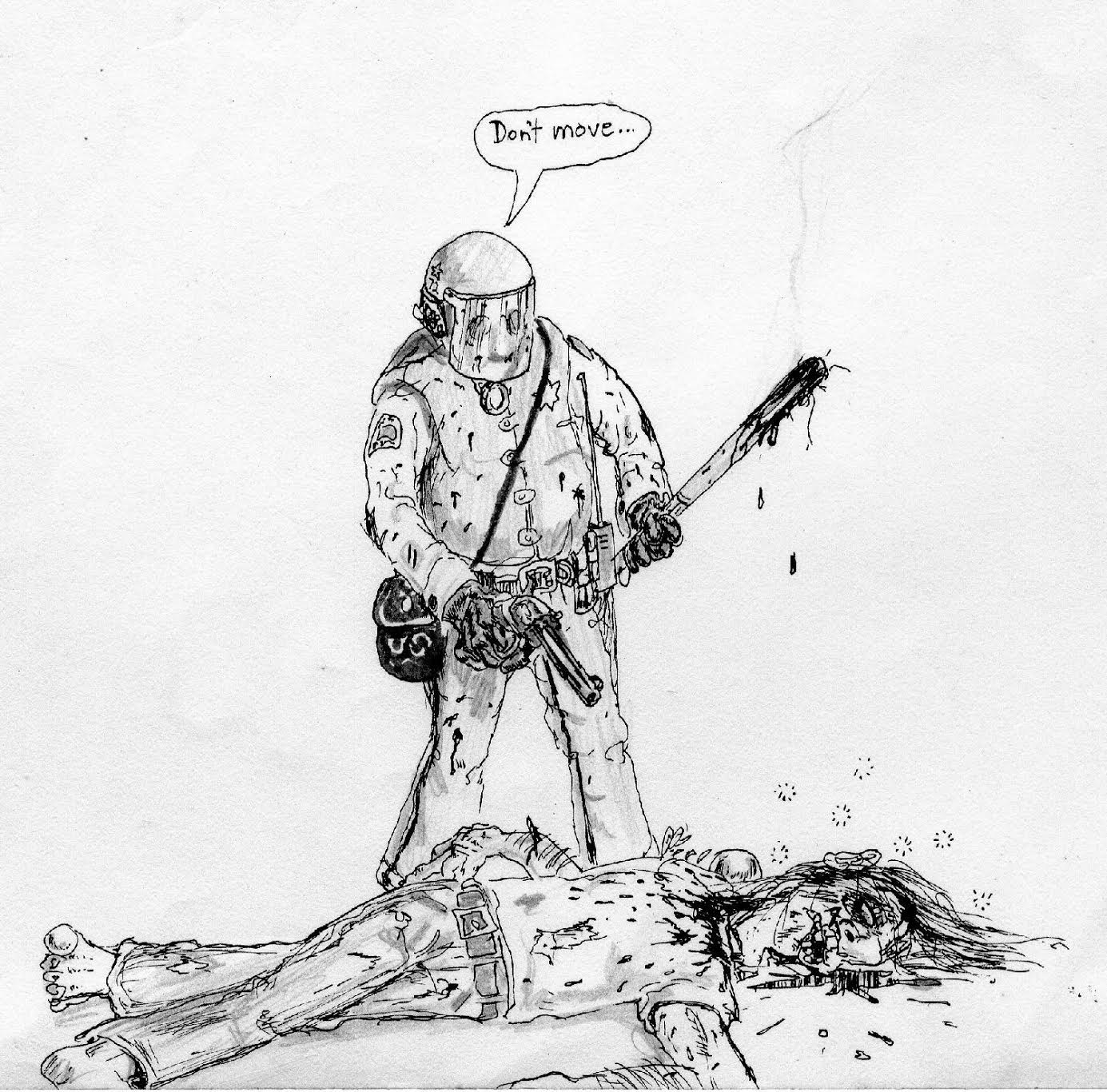

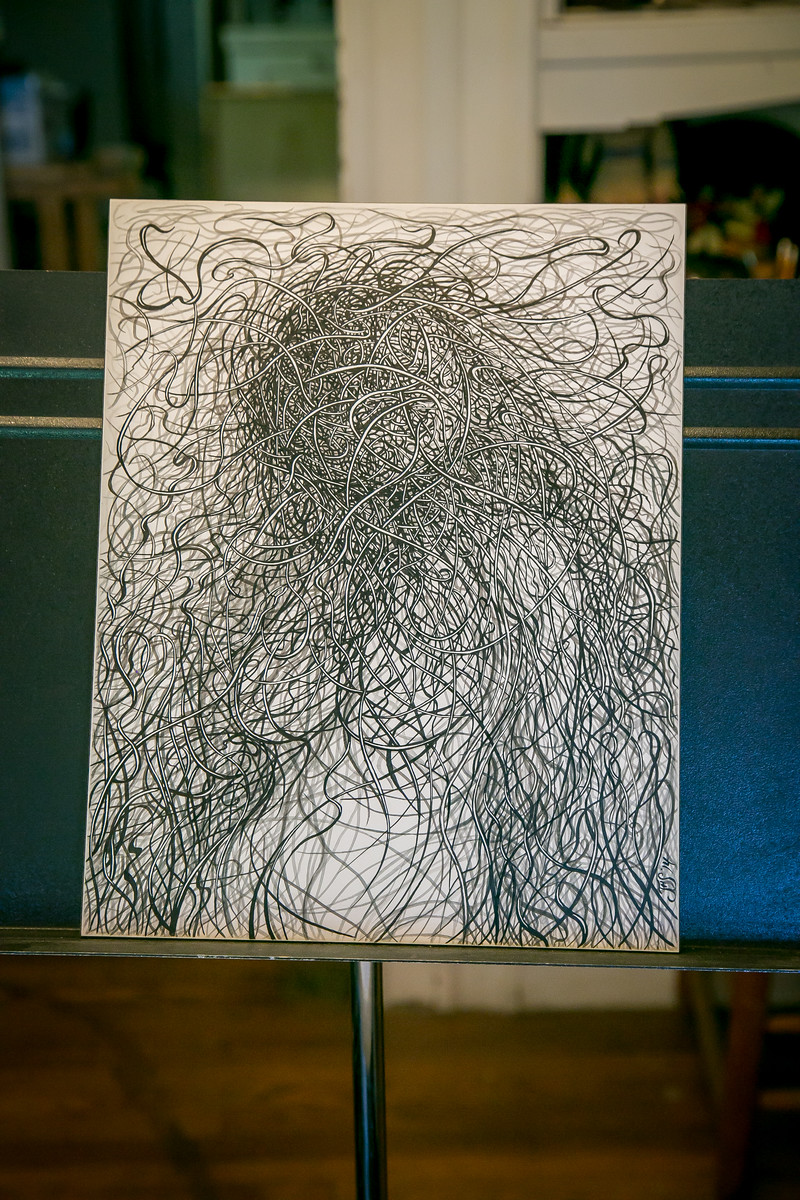

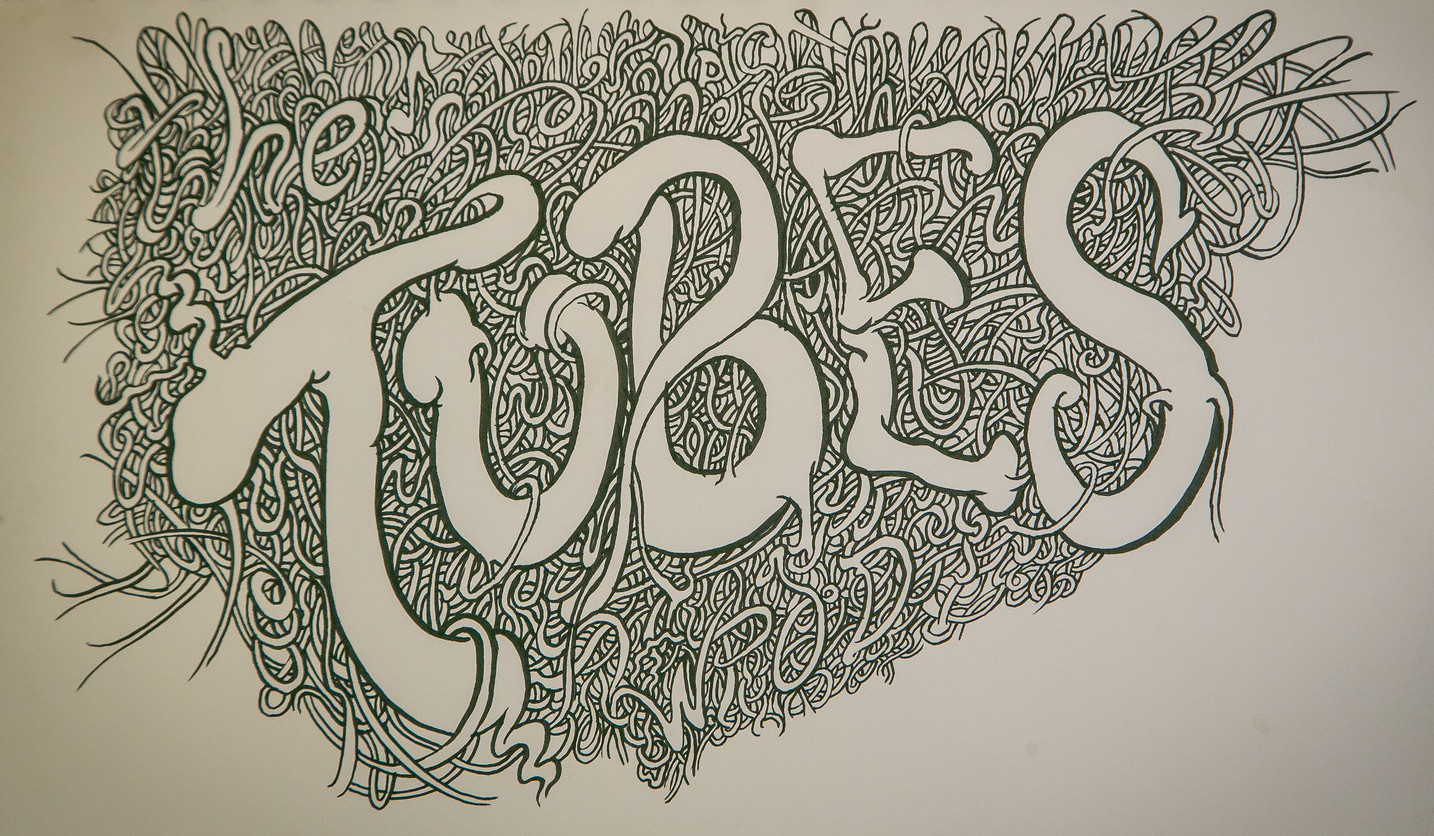

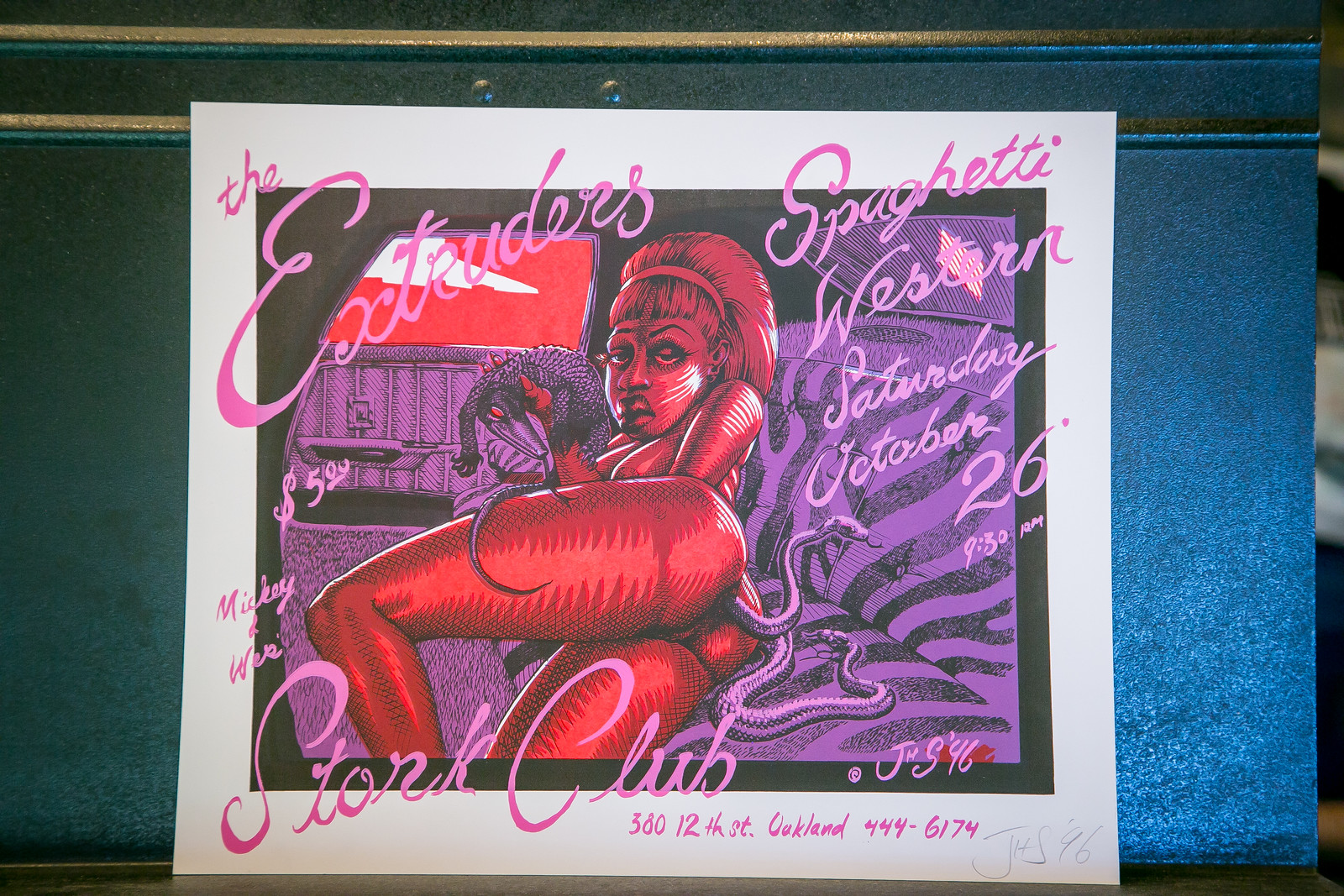

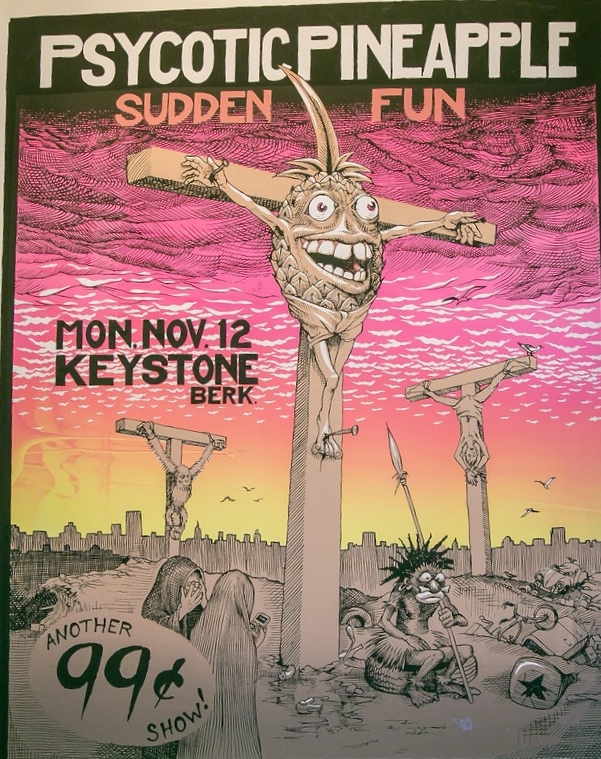

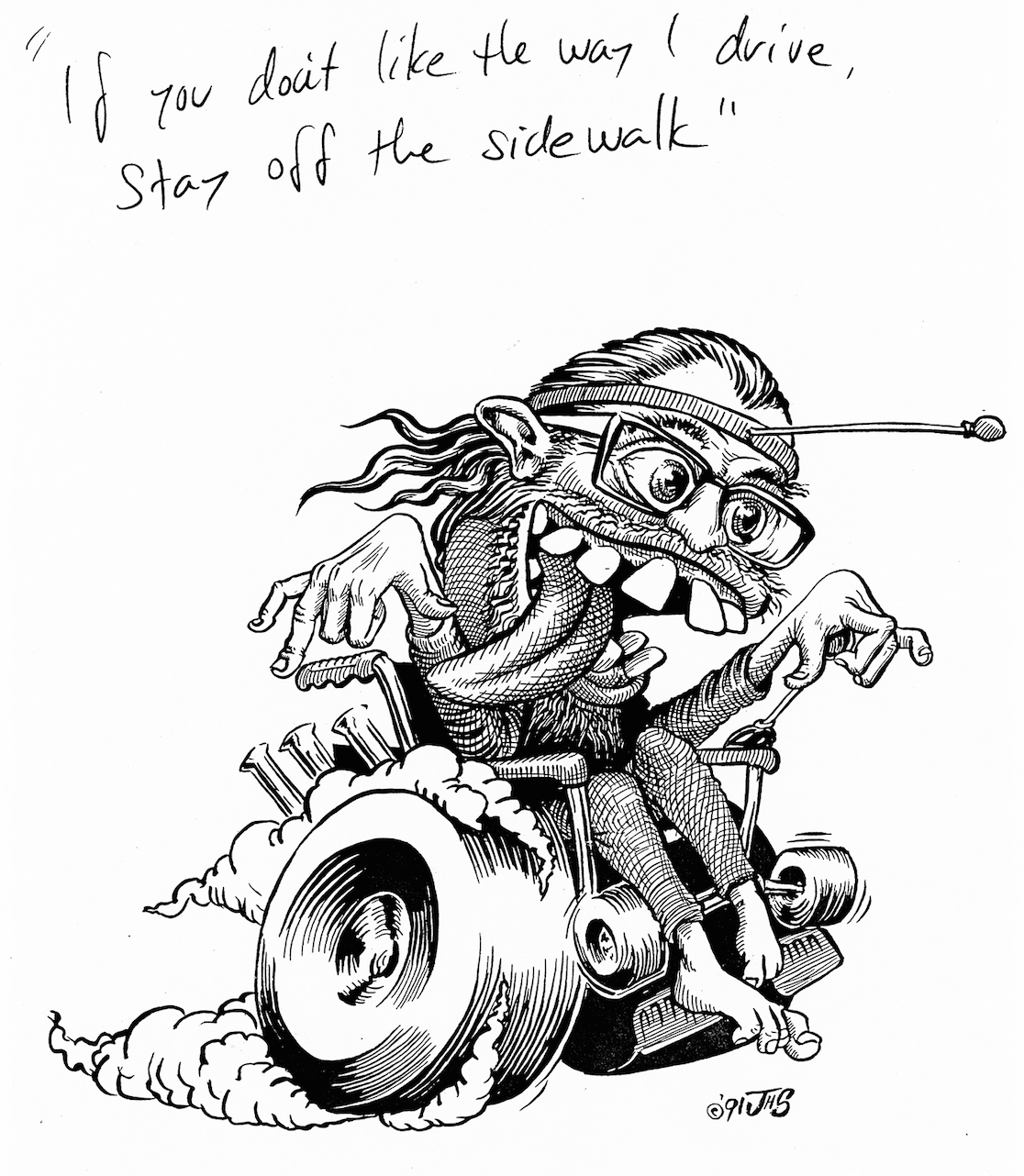

Here are a few examples of Seabury’s very early drawings:

Seabury was motivated by a hard-ass principal who gave him $10 and 10 credits for a ceramic chess set that Seabury made. Those 10 credits got him out of high school.

Seabury finagled his way into the San Francisco Art Institute in January, 1976, only six months after graduating from high school and thus six months shy of the one-year “life experience” that SFAI required for admission.

He worked on etchings and silk screening, but was getting uninspired.

Then he met Ron Nagle. Nagle is known for small-scale, refined ceramic sculptures of great detail and compelling color. From 1961 until 1978 he taught ceramics at SFAI. He inspired Seabury.

Seabury says “we had the same books on our shelves.” His friendship with Nagle led to a couple of teaching assistant jobs. “We mostly talked about music.”

After three years, Seabury left SFAI and since then has made his living with his art and his guitar, almost always avoiding a full-time day job. A part-time gig assembling blow torches in a factory in San Leandro reminded him that he was not cut out for the blue collar life.

The music scene around which Seabury has revolved is made up of Berkeley/Bay Area bands – the power-pop Rubinoos, the pop/rock Little Roger and the Goosebumps, the Psycotic Pineapple, and Pyno Jam. And different iterations and permutations and variations of personnel.

Pyscotic Pineapple got its name through a word association game that Tommy Dunbar and Jon Rubin were played. One said “PSYCHOTIC” and the response was “PINEAPPLE.”

There are several stories about the no “h” spelling. Seabury tells it like this: he was creating letters for a diffraction grating (an optical component with a periodic structure, which splits and diffracts light into several beams travelling in different directions) project for his Hofner bass case. When he finished he saw that he had left out the “H.” It stayed no H. As I said, there are other stories.

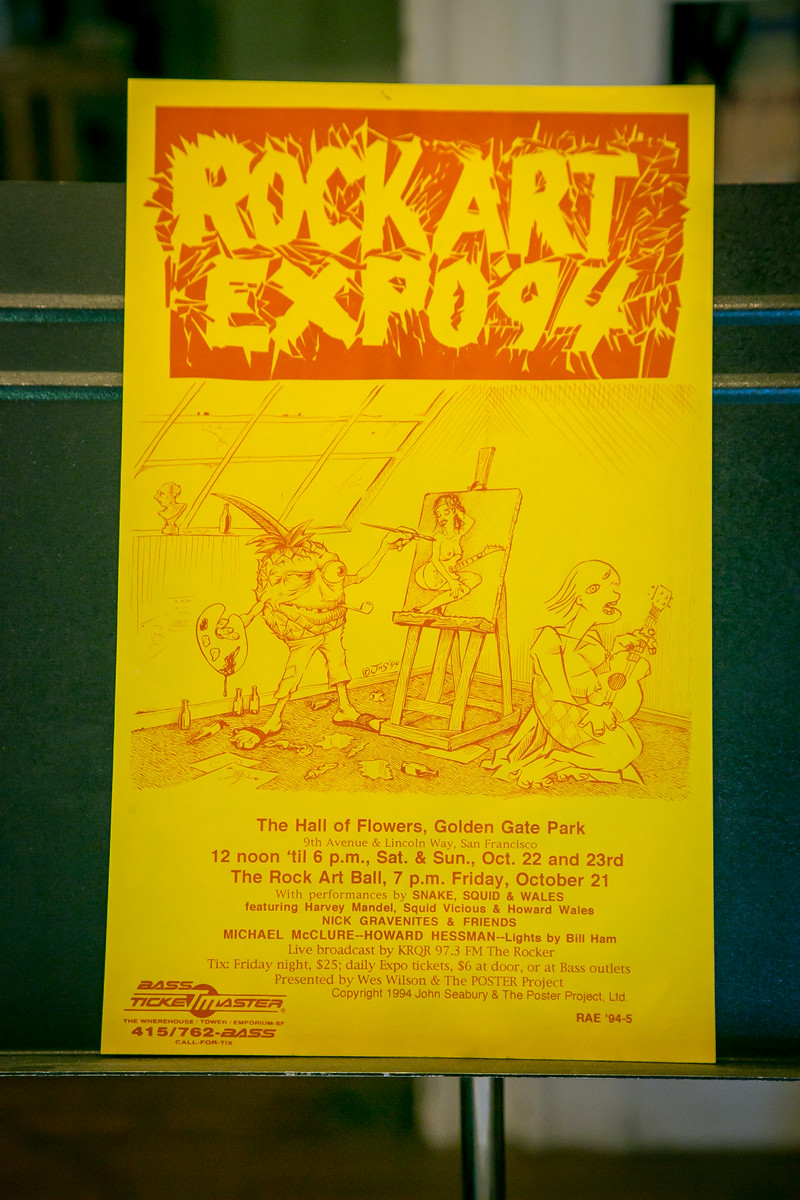

Music alone paid rent into the nineties. Concert posters and graphic art then became the breadwinners. The standard rock industry model is no upfront money for the poster, but you sell posters and the concerts and make your money that way. That’s the way he worked for a while.

Seabury now works with Moonalice, a psychedelic, roots-rock band without a label. They pay him upfront and give their posters away. They have been consistently touring the United States and Canada since 2007

I asked him about the influences on his art. He reflexively said “New Yorker cartoons” and then went a little deeper.

Albrecht Dürer was a 16th century German painter and printmaker.

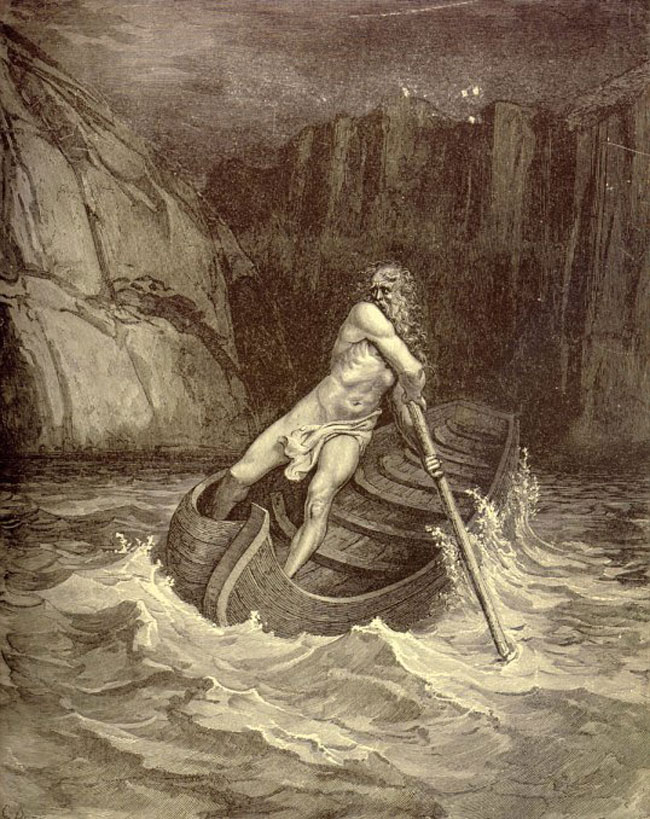

Gustave Doré was a 19th century French printmaker. His illustrations form our sense of Dante. Seabury’s parents had a copy of a Doré-illustrted Dante that captivated a young John.

While at the Art Institute, Seabury was required to write a paper on an artist whom he liked. He waited until the last minute, and then plunged into an essay on Doré. Doing his research, he learned that Doré only did pencil drawings and that he relied on his engravers to fill in the details. The professor who graded Seabury’s paper caught the undercurrent of disdain which had come to color Seabury’s view of Doré. He asked Seabury why he chose an artist he didn’t like. Seabury explained – there was no time to do a second artist so he went with what he had.

Salvador Dali, a 20th century Spanish surrealist, is an inspiration.

And then on the contemporary front:

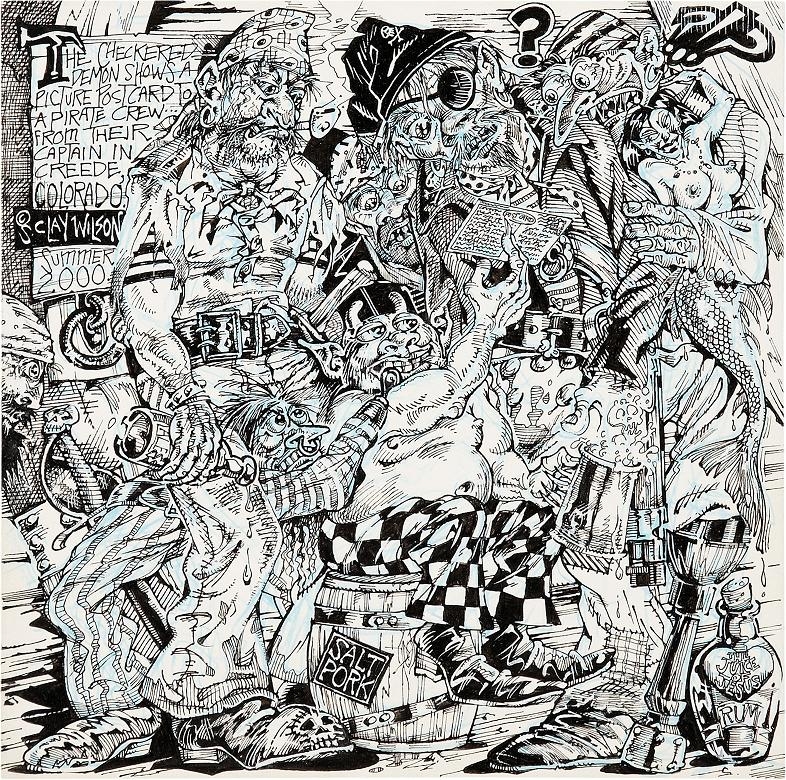

S. Clay Wilson, an underground comic artist whose most well-known character is shown here, the Checkered Demon. As is the case with Durer and Doré, Wilson liked to fill the panel. Wilson called his obsession “graphic agoraphobia.” I introduced Seabury to the term horror vacui – the compulsion that leads an artist to the filling of the entire surface of a space or an artwork with detail.

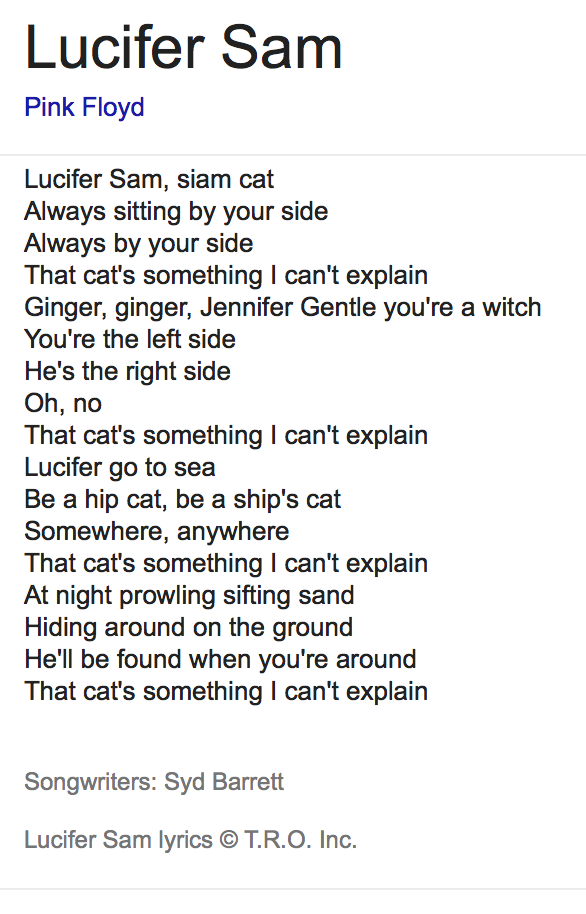

Nowadays Seabury shares his life with a feral Siamese cat.

Seabury calls the cat Lucifer Sam.

Lucifer Sam is a song from Pink Floyd’s 1967 Piper at the Gates of Dawn.

Lucifer Sam is a song from Pink Floyd’s 1967 Piper at the Gates of Dawn.

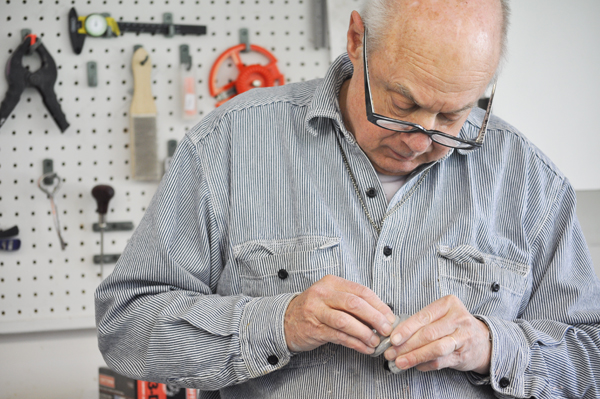

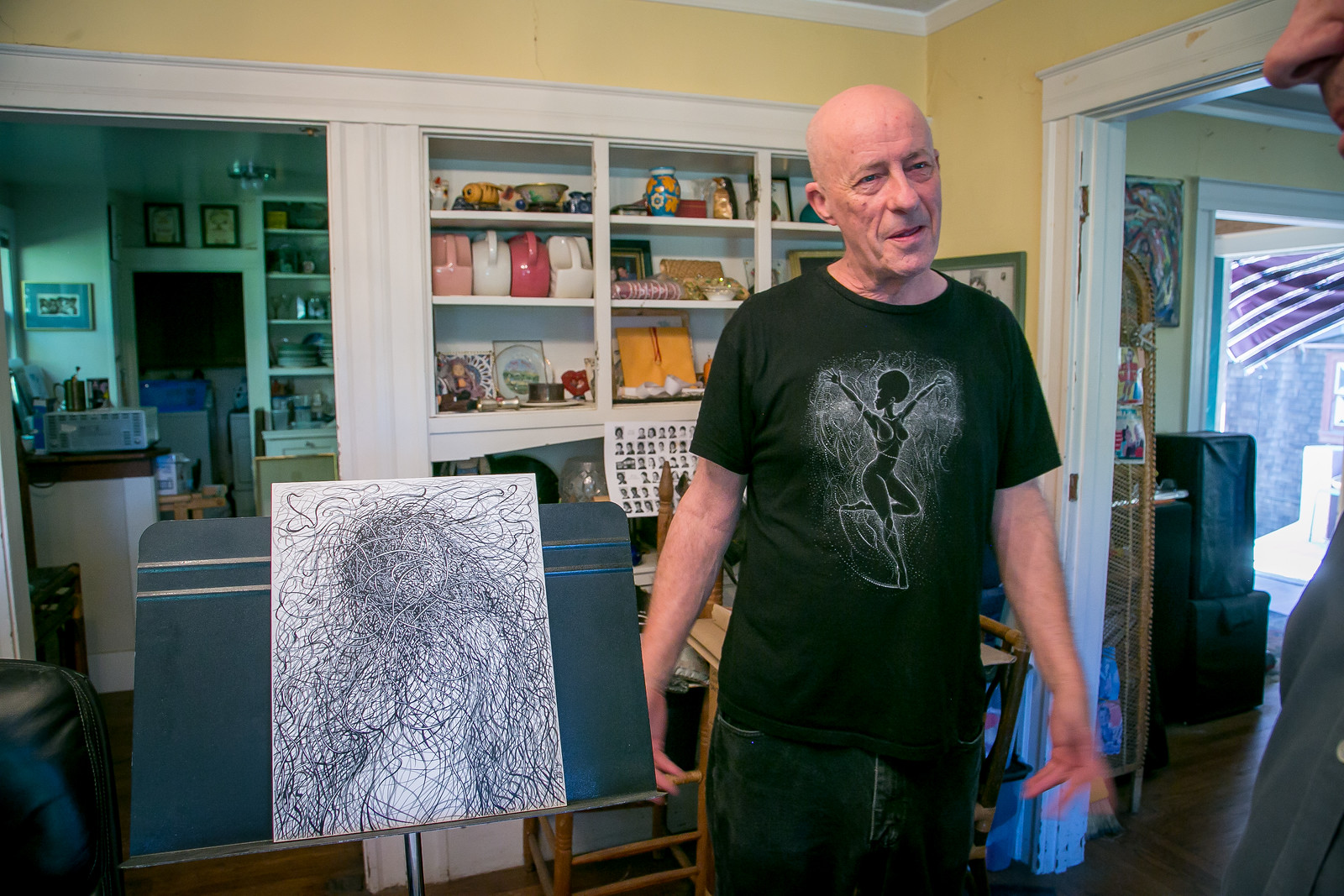

John’s art is easily found on the web, on Facebook or his website. He is prolific, always drawing. Here is a sample of work in progress when we visited:

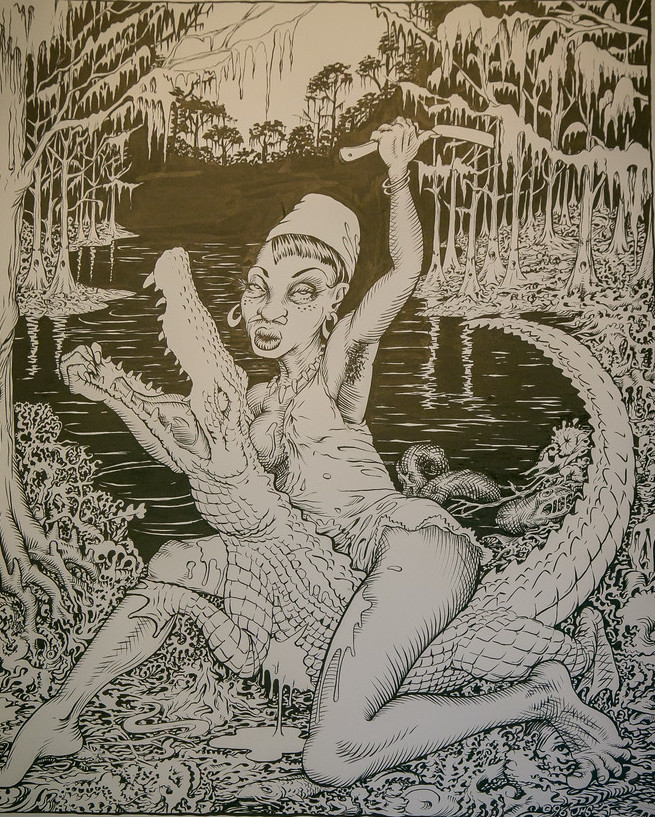

Continuing with unpublished work, here is a sample:

Seabury submitted the poster below to Lindsay Kuhn for consideration for Kuhn’s Swamp Records.

Kuhn rejected Swamp Girl He didn’t think she was sexy enough.

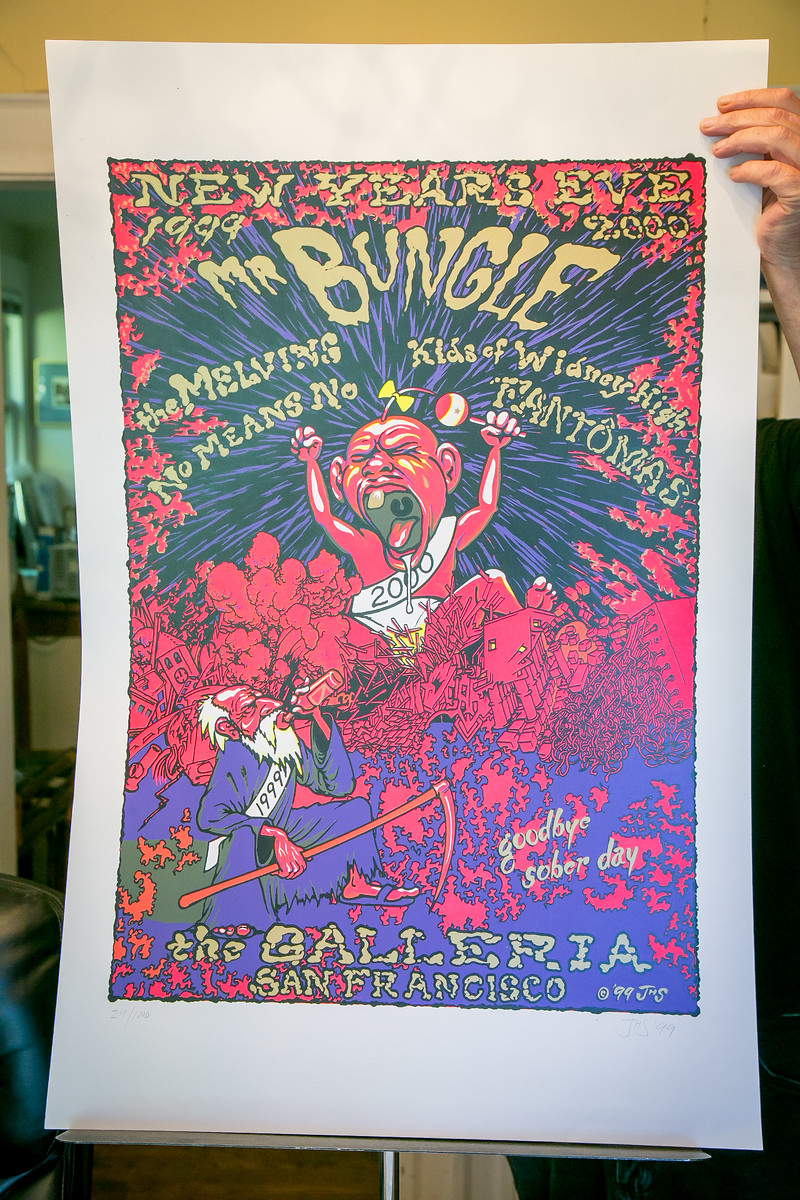

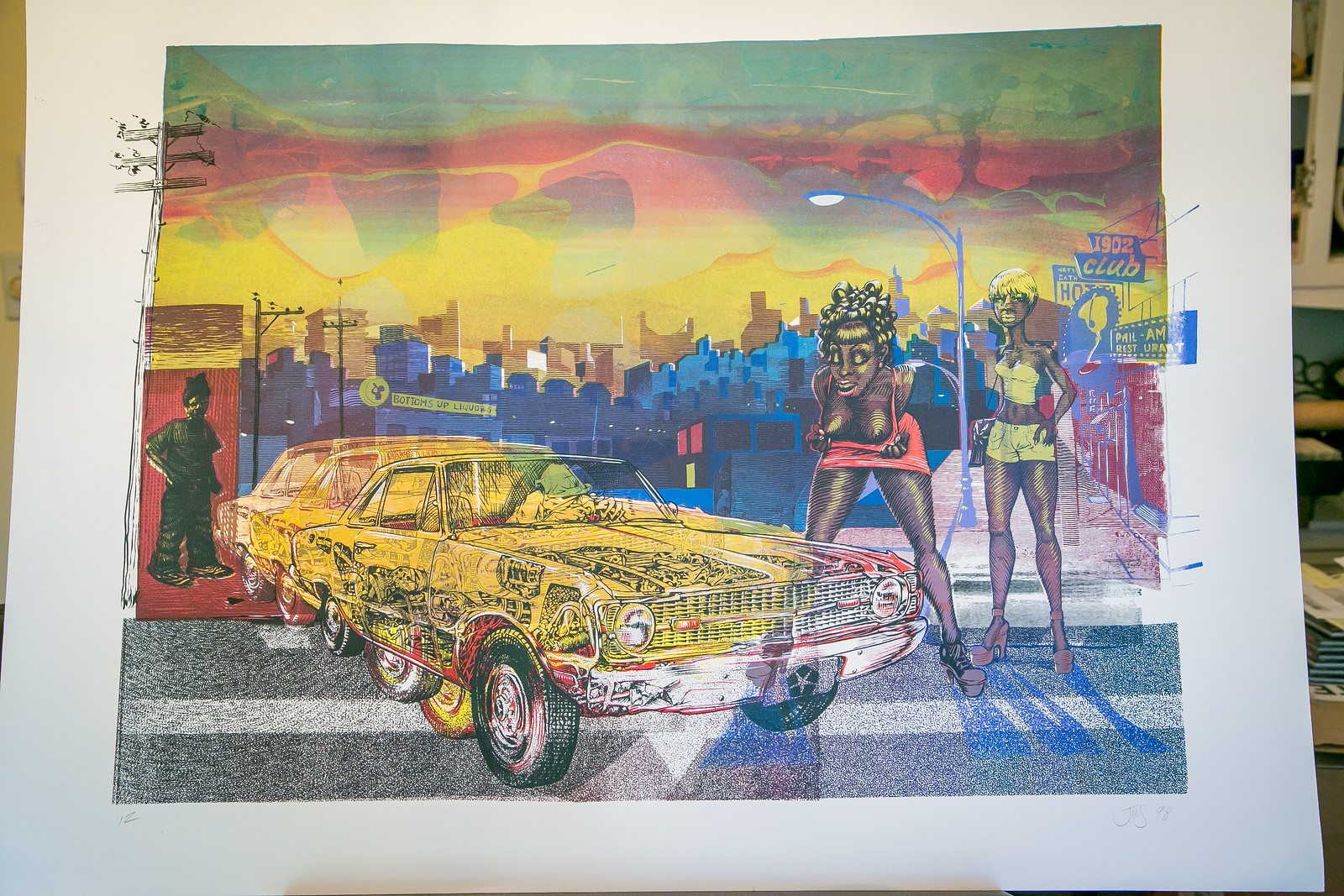

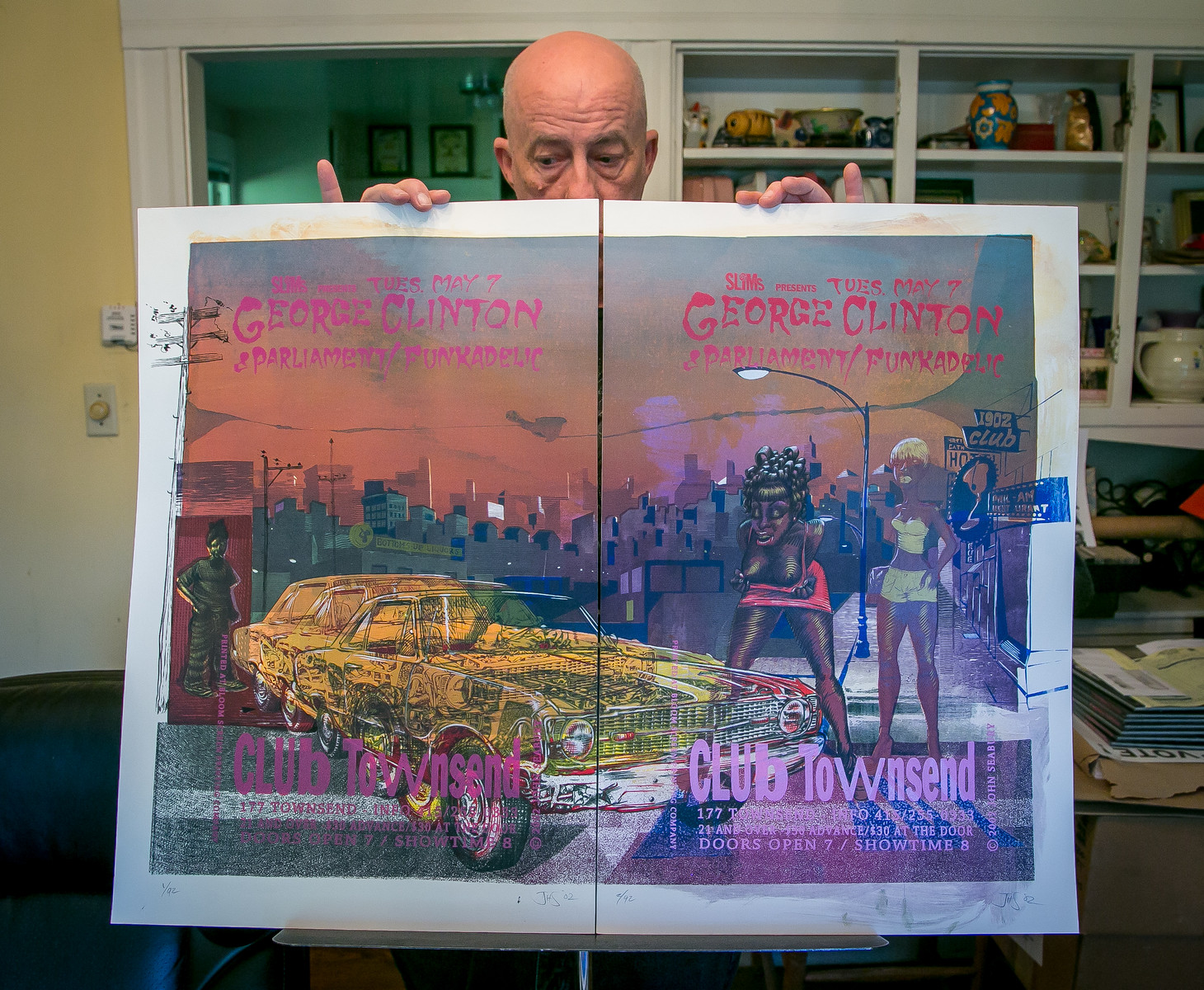

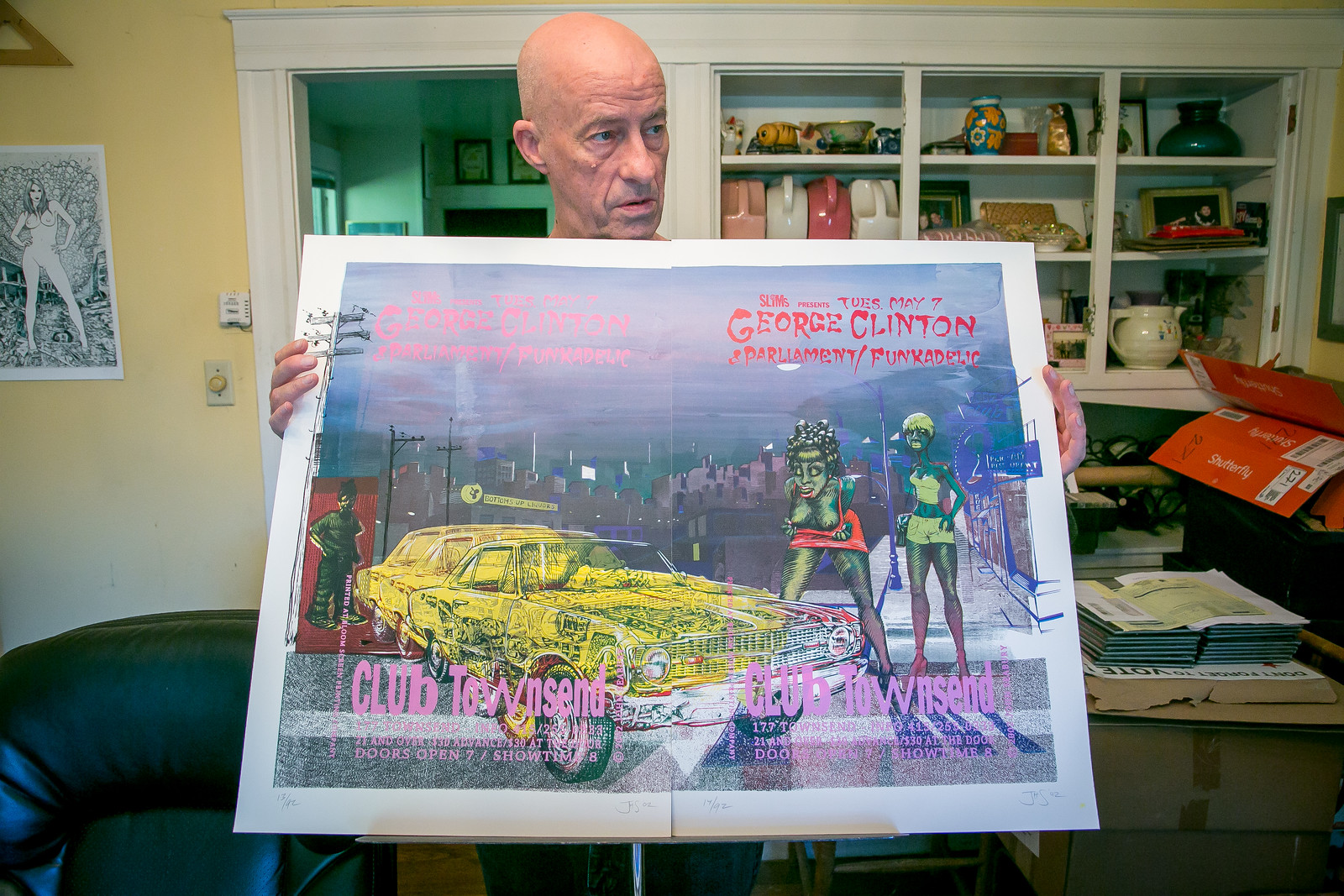

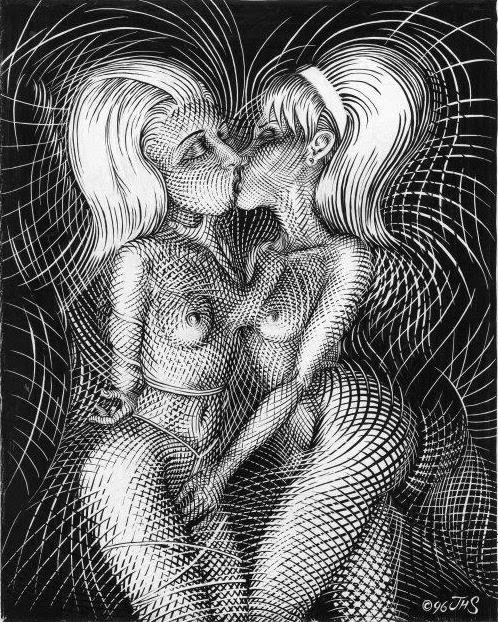

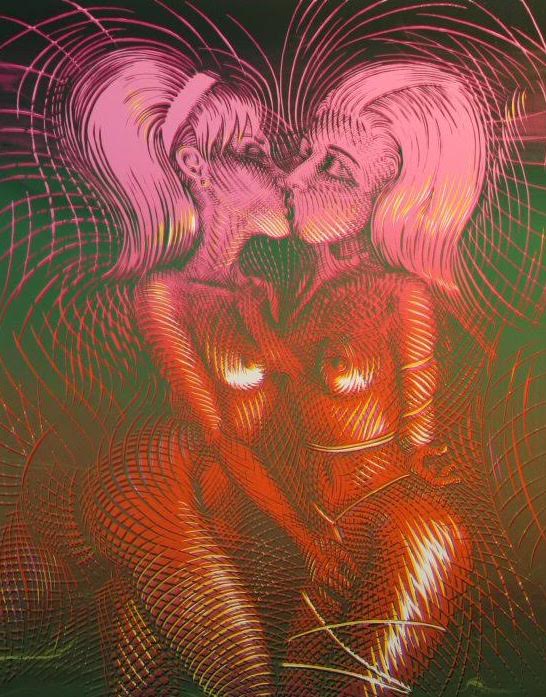

Lastly with graphic arts, Seabury at times uses a split fountain for silkscreening. The ink tray is known as a fountain. With a split fountain, the artist puts two or more colors in the fountain, producing colorful pieces without the expense of full color. No two pieces are the same.

This is an example of the split fountain work. The sky is different on every printing of the poster.

This is another example.

This is an original art piece, made with a split fountain. Seabury had a bunch left over, which he used for a George Clinton poster – again each one different.

I like this – a lot.

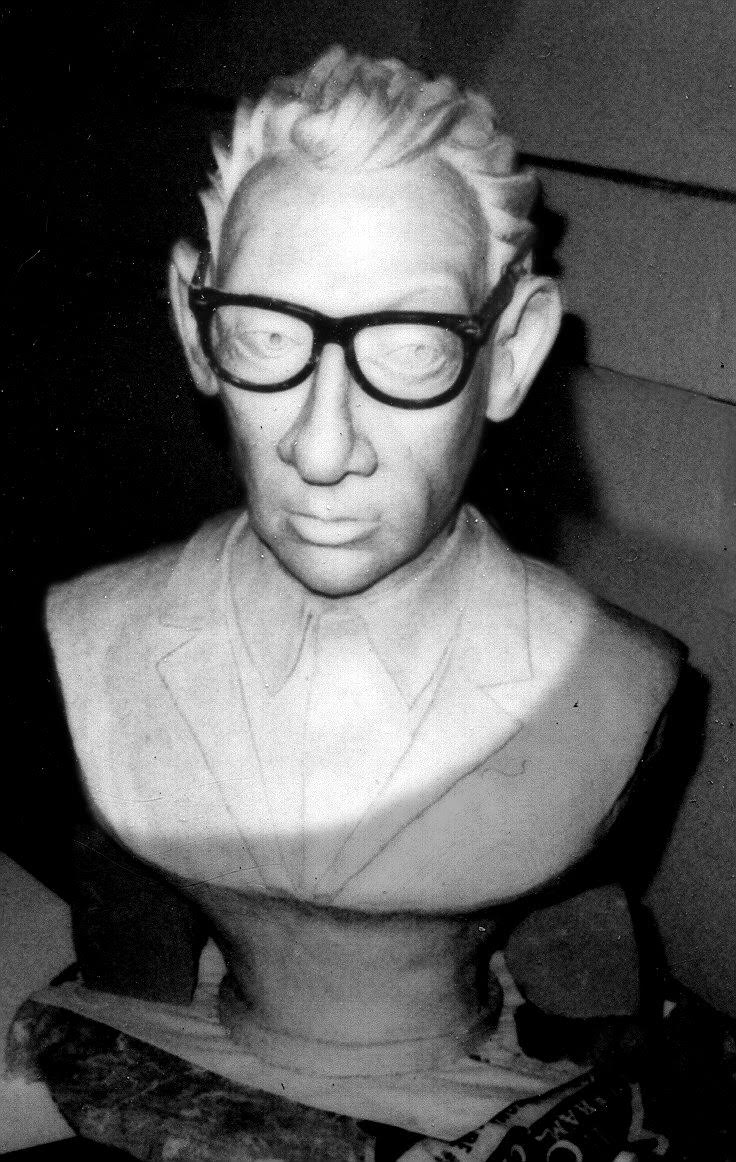

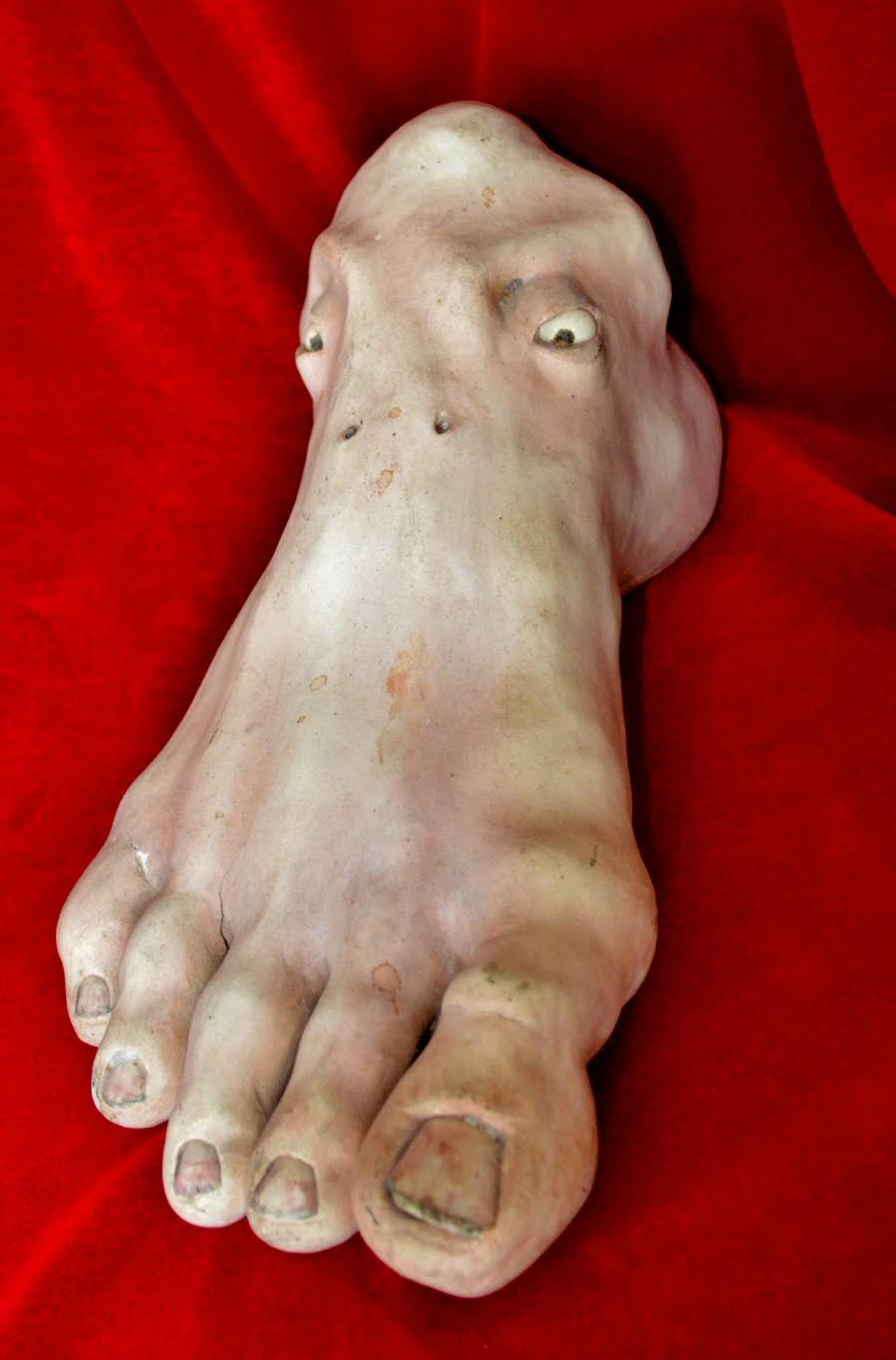

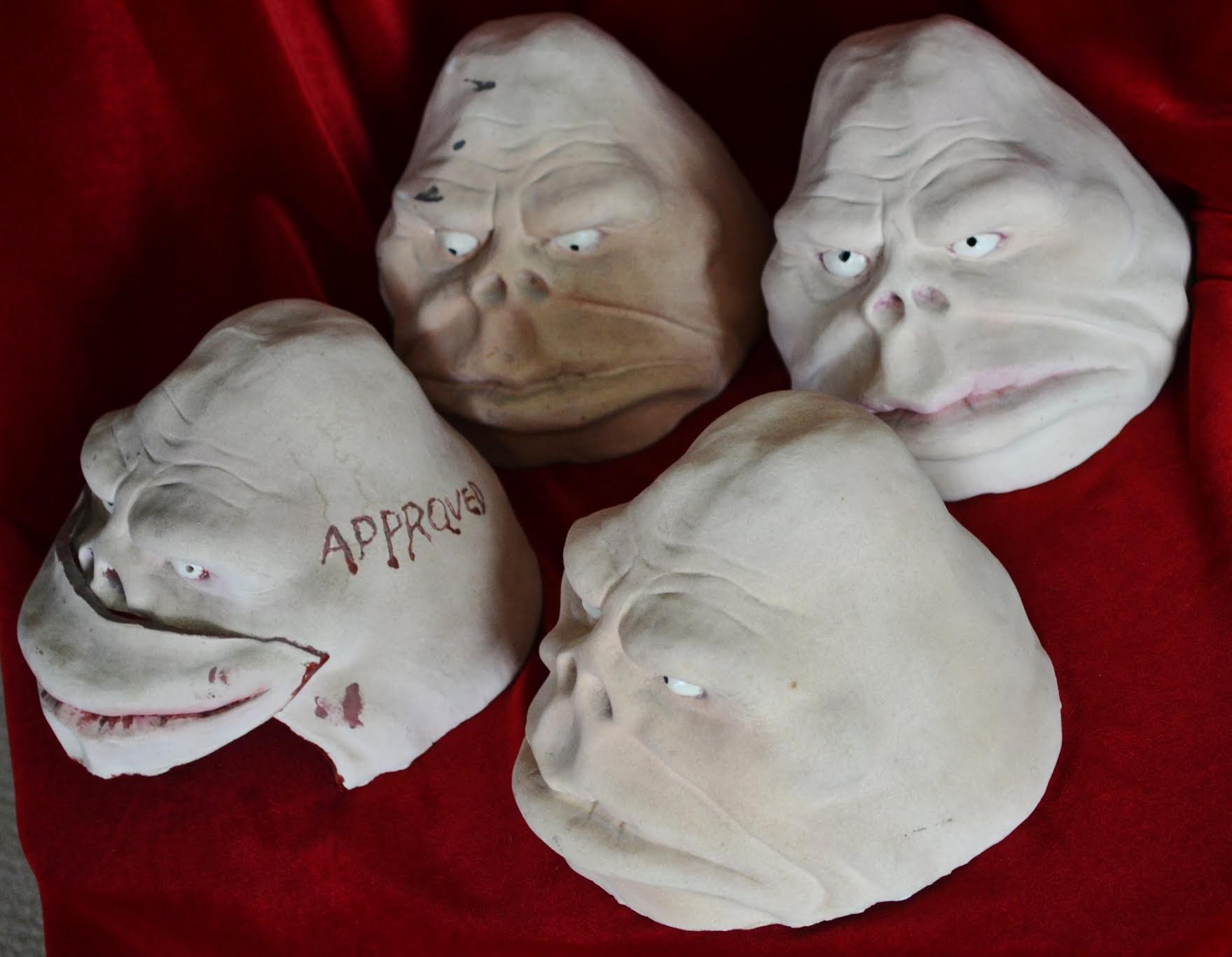

Lastly, Seabury sent me photos of sculpture he made in the 1970s. His SFAI mentor Ron Nagle called this type of work “yuck-yuck ware.” Good name!

This bust of Elvis Costello was commissioned by Rhino Records in the nineties.

So there you have it. A very small fraction of a huge amount of work created by a quirky Son of Berkeley. He sketches all the time – sitting on his porch with Lucifer Sam, at a bar, at a desk at night.

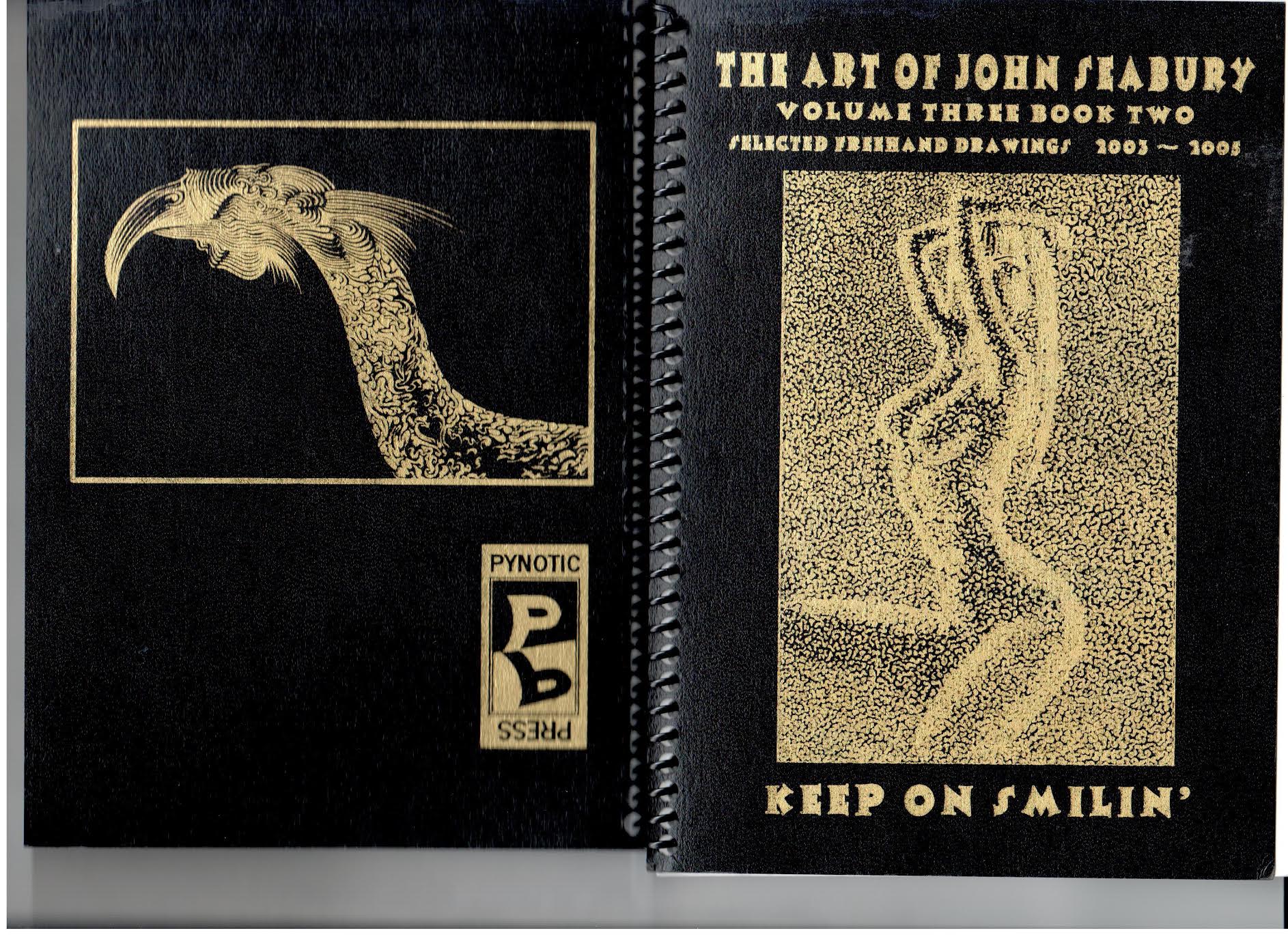

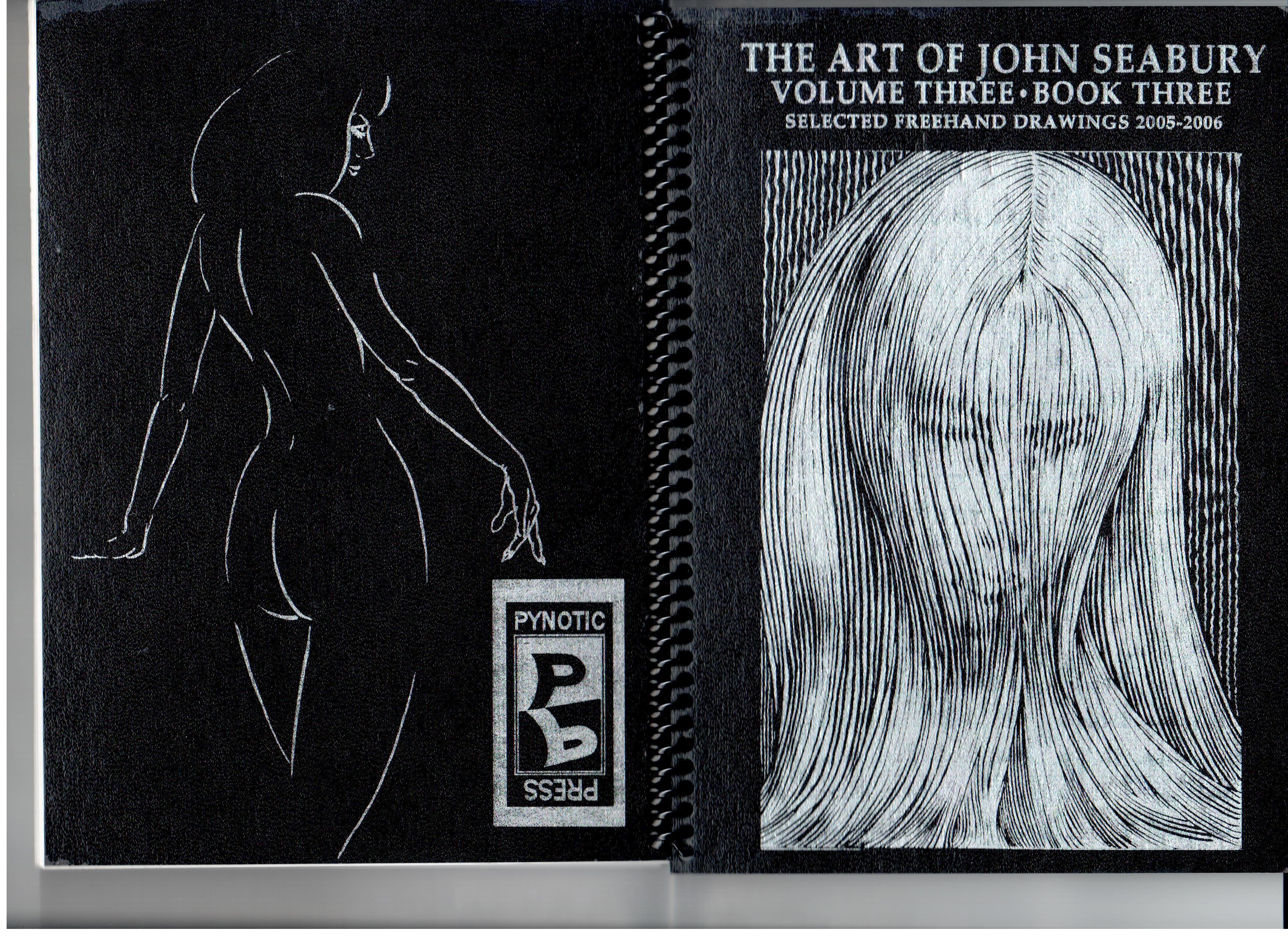

He collects his drawings and sells printed spiral notebooks. They inspire.

Thoreau wrote “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer.” Seabury hears a different drummer.

“Far out depends on where you’re standing” is a Lenny Bruce axiom that says a lot. It’s a variation on the C.S. Lewis quote “What you see and what you hear depends a great deal on where you are standing” but a variation with an edge.

Almost wherever you are standing, John Seabury is far out. So, it was not exactly a surprise when I got an email from Linda Mac who I met as I wrote about Frank Moore the Wounded Healer/Shaman/Performance Artist. Frank Moore was so far out he couldn’t see far out from where he was.

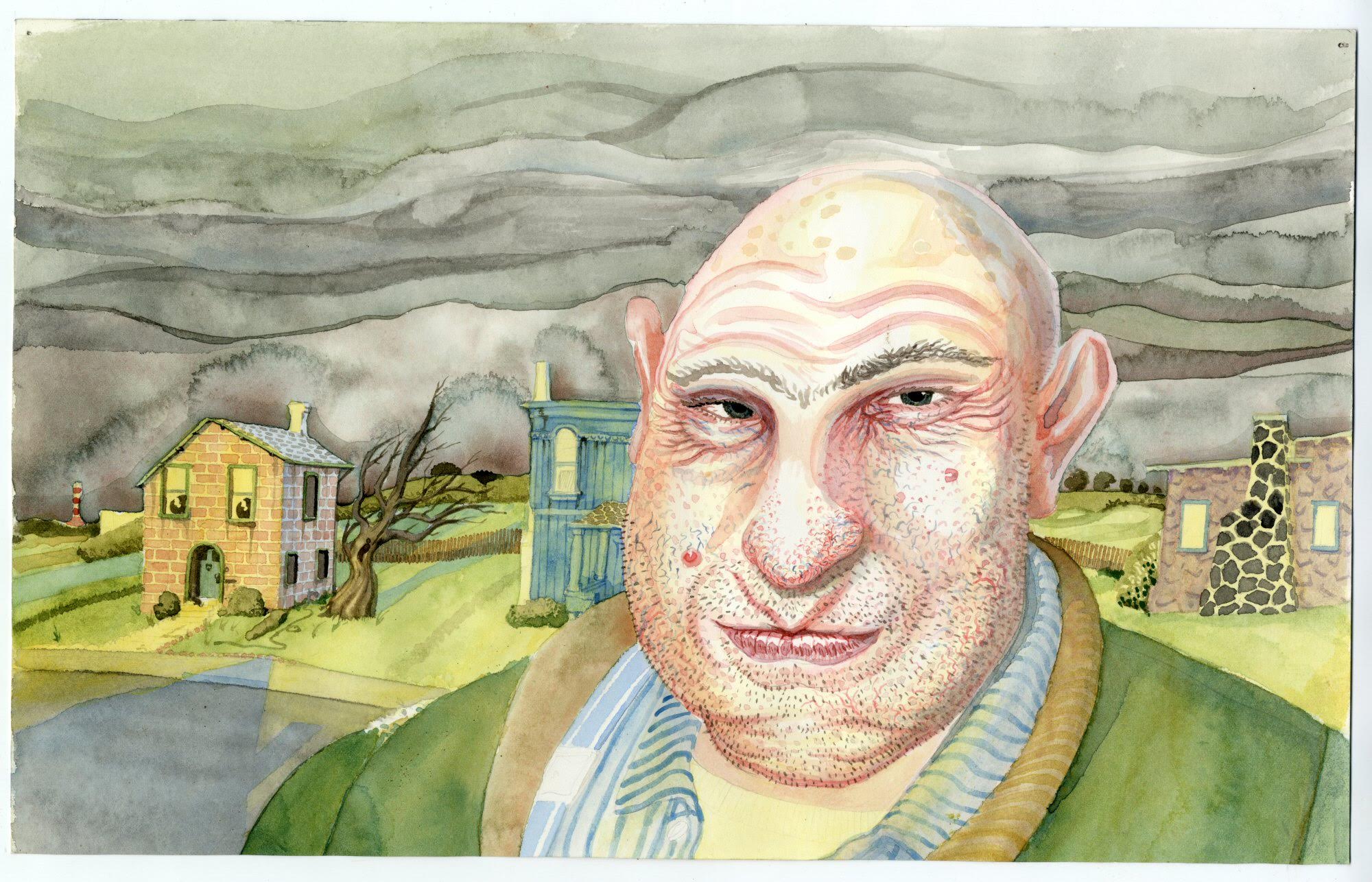

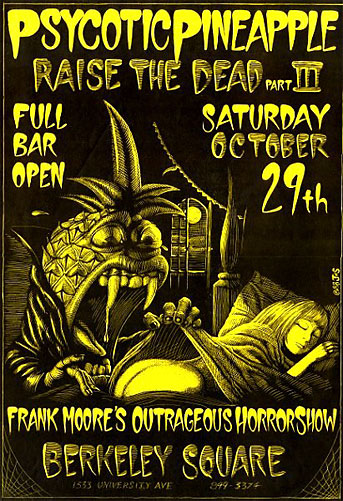

Anyway, Linda told me: “John Seabury came over and Frank modeled for this in the early 1990s. Frank knew John since the 1970s. We performed our Outrageous Horror Show at the Psycotic Pineapple reunion show at the Berkeley Square in 1988 by invitation. We were honored. John also played in Frank’s Cherotic All Star Band.”

This is the poster from that 10/29/88 show.

And this is a drawing that Seabury made of/for Frank Moore as a tee-shirt design:.

Seabury wrote me this about working with Moore: “Frank Moore was THE quirky Berkeleyan. My first glimpse of him was at the Northside Theater. I was sitting in front and did not notice him. It was a Buster Keaton movie, and every time someting really funny happened, I’d hear this miserable moaning behind me. I was thinking, what’s wrong with that guy? Why is he crying at Buster Keaton? I got a good look at him when leaving. I later realized that that was how he laughs! We got to be friends during the Pyno days, we shared the bill a couple of times. I also joined the show on guitar a few times.”

“Later I was invited to do a cover graphic for the Cherotic Evolutionary. They also hosted a solo performance by me on their webcast.”

It is no accident that these two men from far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the Western spiral arm of the galaxy knew each other and performed together.

I showed my friend the draft post.

“I dig his metaphor – same books on the shelf, him and Nagle. It’s good when people have the same books on the shelf.”

What about the post?

He wasn’t done. “I did my share of load-ins and load-outs for Little Roger and the Goosebumps. Berkeley was Berkeley then.”

Yes, it was. And in their own way, Mappie and Paul and John and Dave are all manifestations of what worked about Berkeley and what drew people here.

But, once again, what about the post?