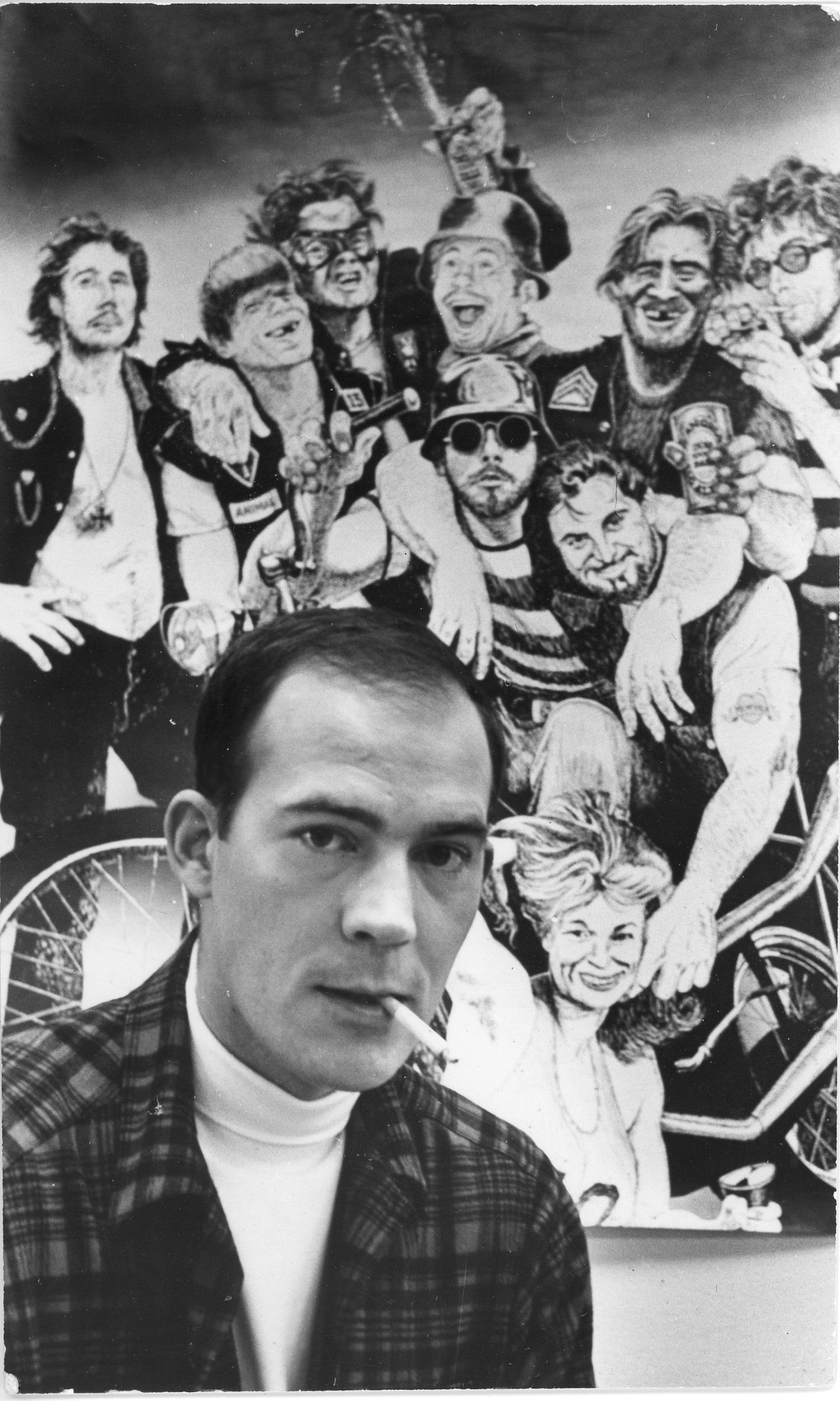

Hunter S. Thompson. Random House book party, February 16, 1967 (the official publication date of the first printing) celebrating the release of his book “Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs.” Photo courtesy of the Estate of Fred W. McDarrah

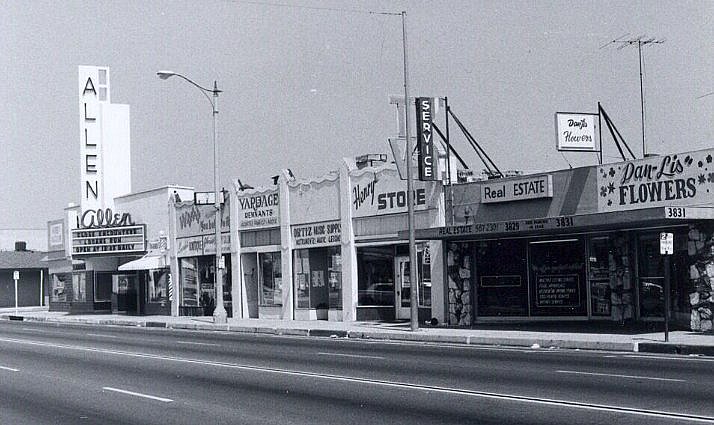

Hunter Thompson moved to San Francisco in 1964. In 1965 Carey McWilliams, editor of The Nation, hired Thompson to write a story about the Hells Angels motorcycle club in California. The article appeared on May 17, 1965.

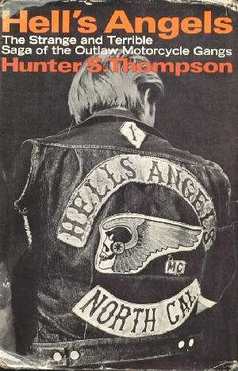

Random House published Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs in 1966,

Here is the article from the Nation:

Last Labor Day weekend newspapers all over California gave front-page reports of a heinous gang rape in the moonlit sand dunes near the town of Seaside on the Monterey Peninsula. Two girls, aged 14 and 15, were allegedly taken from their dates by a gang of filthy, frenzied, boozed-up motorcycle hoodlums called “Hell’s Angels,” and dragged off to be “repeatedly assaulted.”

A deputy sheriff, summoned by one of the erstwhile dates, said he “arrived at the beach and saw a huge bonfire surrounded by cyclists of both sexes. Then the two sobbing, near-hysterical girls staggered out of the darkness, begging for help. One was completely nude and the other had on only a torn sweater.”

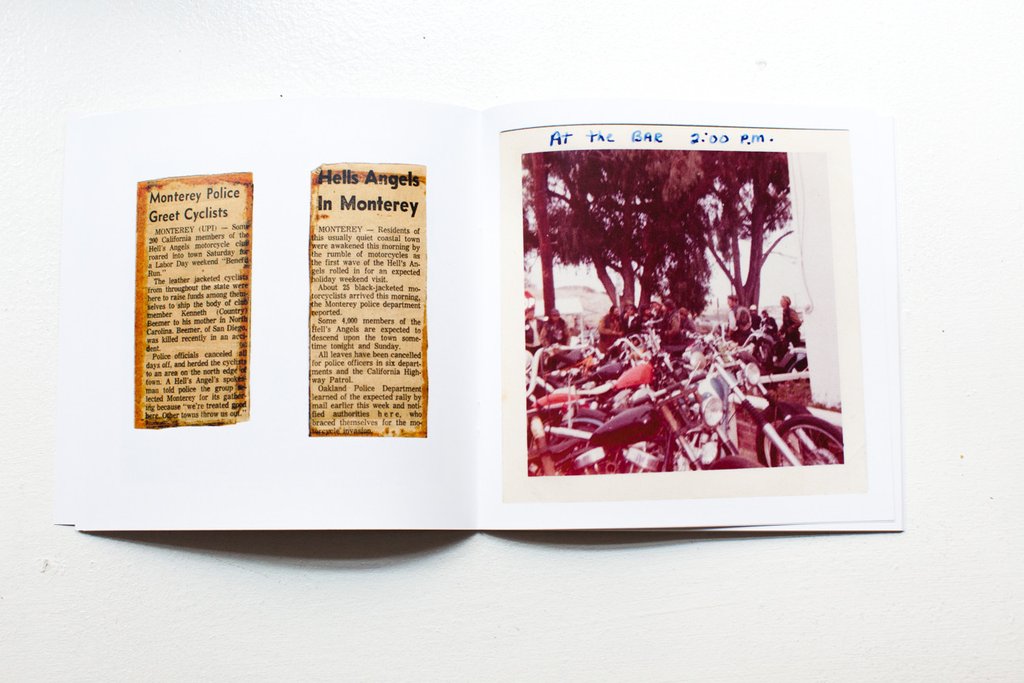

Some 300 Hell’s Angels were gathered in the Seaside-Monterey area at the time, having convened, they said, for the purpose of raising funds among themselves to send the body of a former member, killed in an accident, back to his mother in North Carolina. One of the Angels, hip enough to falsely identify himself as “Frenchy of San Bernardino,” told a reporter who came out to meet the cyclists: “We chose Monterey because we get treated good here; most other places we get thrown out of town.”

But Frenchy spoke too soon. The Angels weren’t on the peninsula twenty-four hours before four of them were in jail for rape, and the rest of the troop was being escorted to the county line by a large police contingent. Several were quoted, somewhat derisively, as saying: “That rape charge against our guys is phony and it won’t stick.”

It turned out to be true, but that was another story and certainly no headliner. The difference between the Hell’s Angels in the paper and the Hell’s Angels for real is enough to make a man wonder what newsprint is for. It also raises a question as to who are the real hell’s angels.

Ever since World War II, California has been strangely plagued by wild men on motorcycles. They usually travel in groups of ten to thirty, booming along the highways and stopping here are there to get drunk and raise hell. In 1947, hundreds of them ran amok in the town of Hollister, an hour’s fast drive south of San Francisco, and got enough press to inspire a film called The Wild One, starring Marlon Brando. The film had a massive effect on thousands of young California motorcycle buffs; in many ways, it was their version of The Sun Also Rises.

The California climate is perfect for motorcycles, as well as surfboards, swimming pools and convertibles. Most of the cyclists are harmless weekend types, members of the American Motorcycle Association, and no more dangerous than skiers or skin divers. But a few belong to what the others call “outlaw clubs,” and these are the ones who–especially on weekends and holidays–are likely to turn up almost anywhere in the state, looking for action. Despite everything the psychiatrists and Freudian casuists have to say about them, they are tough, mean and potentially as dangerous as a pack of wild boar. When push comes to shove, any leather fetishes or inadequacy feelings that may be involved are entirely beside the point, as anyone who has ever tangled with these boys will sadly testify. When you get in an argument with a group of outlaw motorcyclists, you can generally count your chances of emerging unmaimed by the number of heavy-handed allies you can muster in the time it takes to smash a beer bottle. In this league, sportsmanship is for old liberals and young fools. “I smashed his face,” one of them said to me of a man he’d never seen until the swinging started. “He got wise. He called me a punk. He must have been stupid.”

The most notorious of these outlaw groups is the Hell’s Angels, supposedly headquartered in San Bernardino, just east of Los Angeles, and with branches all over the state. As a result of the infamous “Labor Day gang rape,” the Attorney General of California has recently issued an official report on the Hell’s Angels. According to the report, they are easily identified:

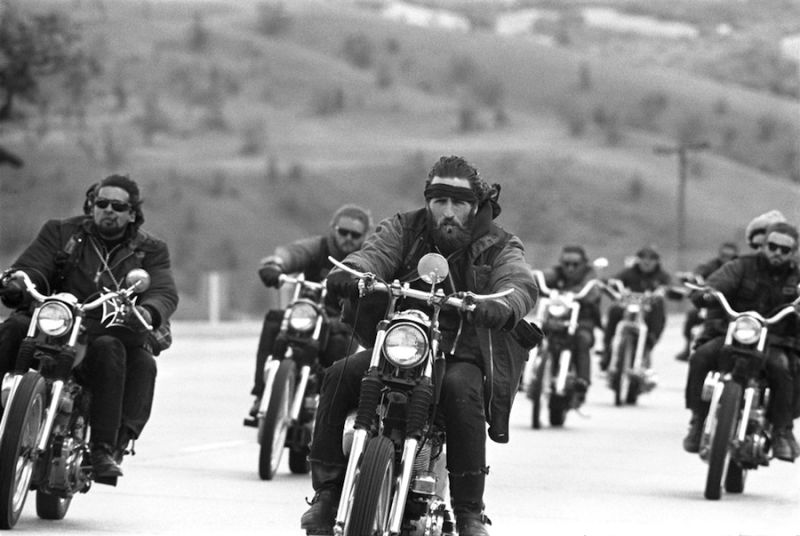

The emblem of the Hell’s Angels, termed “colors,” consists of an embroidered patch of a winged skull wearing a motorcycle helmet. Just below the wing of the emblem are the letters “MC.” Over this is a band bearing the words “Hell’s Angels.” Below the emblem is another patch bearing the local chapter name, which is usually an abbreviation for the city or locality. These patches are sewn on the back of a usually sleeveless denim jacket. In addition, members have been observed wearing various types of Luftwaffe insignia and reproductions of German iron crosses.* (*Purely for decorative and shock effect. The Hell’s Angels are apolitical and no more racist than other ignorant young thugs.) Many affect beards and their hair is usually long and unkempt. Some wear a single earring in a pierced ear lobe. Frequently they have been observed to wear metal belts made of a length of polished motorcycle drive chain which can be unhooked and used as a flexible bludgeon… Probably the most universal common denominator in identification of Hell’s Angels is generally their filthy condition. Investigating officers consistently report these people, both club members and their female associates, seem badly in need of a bath. Fingerprints are a very effective means of identification because a high percentage of Hell’s Angels have criminal records.

In addition to the patches on the back of Hell’s Angel’s jackets, the “One Percenters” wear a patch reading “1%-er.” Another badge worn by some members bears the number “13.” It is reported to represent the 13th letter of the alphabet, “M,” which in turn stands for marijuana and indicates the wearer thereof is a user of the drug.

The Attorney General’s report was colorful, interesting, heavily biased and consistently alarming–just the sort of thing, in fact, to make a clanging good article for a national news magazine. Which it did; in both barrels. Newsweek led with a left hook titled “The Wild Ones,” Time crossed right, inevitably titled “The Wilder Ones.” The Hell’s Angels, cursing the implications of this new attack, retreated to the bar of the DePau Hotel near the San Francisco waterfront and planned a weekend beach party. I showed them the articles. Hell’s Angels do not normally read the news magazines. “I’d go nuts if I read that stuff all the time,” said one. “It’s all bullshit.”

Newsweek was relatively circumspect. It offered local color, flashy quotes and “evidence” carefully attributed to the official report but unaccountably said the report accused the Hell’s Angels of homosexuality, whereas the report said just the opposite. Time leaped into the fray with a flurry of blood, booze and semen-flecked wordage that amounted, in the end, to a classic of supercharged hokum: “Drug-induced stupors… no act is too degrading… swap girls, drugs and motorcycles with equal abandon… stealing forays… then ride off again to seek some new nadir in sordid behavior…”

Where does all this leave the Hell’s Angels and the thousands of shuddering Californians (according to Time) who are worried sick about them? Are these outlaws really going to be busted, routed and cooled, as the news magazines implied? Are California highways any safer as a result of this published uproar? Can honest merchants once again walk the streets in peace? The answer is that nothing has changed except that a few people calling themselves the Hell’s Angels have a new sense of identity and importance.

After two weeks of intensive dealings with the Hell’s Angels phenomenon, both in print and in person, I’m convinced the net result of the general howl and publicity has been to obscure and avoid the real issues by invoking a savage conspiracy of bogeymen and conning the public into thinking all will be “business as usual” once this fearsome snake is scotched, as it surely will be by hard and ready minions of the Establishment.

Meanwhile, according to Attorney General Thomas C. Lynch’s own figures, California’s true crime picture makes the Hell’s Angels look like a gang of petty jack rollers. The police count 463 Hell’s Angels: 205 around L.A. and 233 in the San Francisco-Oakland area. I don’t know about L.A. but the real figures for the Bay Area are thirty or so in Oakland and exactly eleven–with one facing expulsion–in San Francisco. This disparity makes it hard to accept other police statistics. The dubious package also shows convictions on 1,023 misdemeanor counts and 151 felonies–primarily vehicle theft, burglary and assault. This is for all years and all alleged members.

California’s overall figures for 1963 list 1,116 homicides, 12,448 aggravated assaults, 6,257 sex offenses, and 24,532 burglaries. In 1962, the state listed 4,121 traffic deaths, up from 3,839 in 1961. Drug arrest figures for 1964 showed a 101 percent increase in juvenile marijuana arrests over 1963, and a recent back-page story in the San Francisco Examinersaid, “The venereal disease rate among [the city’s] teen-agers from 15-19 has more than doubled in the past four years.” Even allowing for the annual population jump, juvenile arrests in all categories are rising by 10 per cent or more each year.

Against this background, would it make any difference to the safety and peace of mind of the average Californian if every motorcycle outlaw in the state (all 901, according to the state) were garroted within twenty-four hours? This is not to say that a group like the Hell’s Angels has no meaning. The generally bizarre flavor of their offenses and their insistence on identifying themselves make good copy, but usually overwhelm–in print, at least–the unnerving truth that they represent, in colorful microcosm, what is quietly and anonymously growing all around us every day of the week.

“We’re bastards to the world and they’re bastards to us,” one of the Oakland Angels told a Newsweek reporter. “When you walk into a place where people can see you, you want to look as repulsive and repugnant as possible. We are complete social outcasts–outsiders against society.”

A lot of this is a pose, but anyone who believes that’s all it is has been on thin ice since the death of Jay Gatsby. The vast majority of motorcycle outlaws are uneducated, unskilled men between 20 and 30, and most have no credentials except a police record. So at the root of their sad stance is a lot more than a wistful yearning for acceptance in a world they never made; their real motivation is an instinctive certainty as to what the score really is. They are out of the ball game and they know it–and that is their meaning; for unlike most losers in today’s society, the Hell’s Angels not only know but spitefully proclaim exactly where they stand.

I went to one of their meetings recently, and half-way through the night I thought of Joe Hill on his way to face a Utah firing squad and saying his final words: “Don’t mourn, organize.” It is safe to say that no Hell’s Angel has ever heard of Joe Hill or would know a Wobbly from a Bushmaster, but nevertheless they are somehow related. The I.W.W. had serious plans for running the world, while the Hell’s Angels mean only to defy the world’s machinery. But instead of losing quietly, one by one, they have banded together with a mindless kind of loyalty and moved outside the framework, for good or ill. There is nothing particularly romantic or admirable about it; that’s just the way it is, strength in unity. They don’t mind telling you that running fast and loud on their customized Harley 74s gives them a power and a purpose that nothing else seems to offer.

Beyond that, their position as self-proclaimed outlaws elicits a certain popular appeal, however reluctant. That is especially true in the West and even in California where the outlaw tradition is still honored. The unarticulated link between the Hell’s Angels and the millions of losers and outsiders who don’t wear any colors is the key to their notoriety and the ambivalent reactions they inspire. There are several other keys, having to do with politicians, policemen and journalists, but for this we have to go back to Monterey and the Labor Day “gang rape.”

Politicians, like editors and cops, are very keen on outrage stories, and state Senator Fred S. Farr of Monterey County is no exception. He is a leading light of the Carmel-Pebble Beach set and no friend to hoodlums anywhere, especially gang rapists who invade his constituency. Senator Far demanded an immediate investigation of the Hell’s Angels and others of their ilk–Commancheros, Stray Satans, Iron Horsemen, Rattlers (a Negro club), and Booze Fighters–whose lack of status caused them all to be lumped together as “other disreputables.” In the cut-off world of big bikes, long runs and classy rumbles, this new, state-sanctioned stratification made the Hell’s Angels very big. They were, after all, Number One. Like John Dillinger.

Attorney General Lynch, then new in his job, moved quickly to mount an investigation of sorts. He sent questionnaires to more than 100 sheriffs, district attorneys and police chiefs, asking for more information on the Hell’s Angels and those “other disreputables.” He also asked for suggestions as to how the law might deal with them.

Six months went by before all the replies where condensed into the fifteen-page report that made new outrage headlines when it was released to the press. (The Hell’s Angels also got a copy; one of them stole mine.) As a historical document, it read like a plot synopsis of Mickey Spillane’s worst dreams. But in the matter of solutions it was vague, reminiscent in some ways of Madame Nhu’s proposals for dealing with the Vietcong. The state was going to centralize information on these thugs, urge more vigorous prosecution, put them all under surveillance whenever possible, etc.

A careful reader got the impression that even if the Hell’s Angels had acted out this script–eighteen crimes were specified and dozens of others implied–very little would or could be done about it, and that indeed Mr. Lynch was well aware he’d been put, for political reasons, on a pretty weak scent. There was plenty of mad action, senseless destruction, orgies, brawls, perversions and a strange parade of “innocent victims” that, even on paper and in careful police language, was enough to tax the credulity of the dullest police reporter. Any bundle of information off police blotters is bound to reflect a special viewpoint, and parts of the Attorney General’s report are actually humorous, if only for the language. Here is an excerpt:

On November 4, 1961, a San Francisco resident driving through Rodeo, possibly under the influence of alcohol, struck a motorcycle belonging to a Hell’s Angel parked outside a bar. A group of Angels pursued the vehicle, pulled the driver from the car and attempted to demolish the rather expensive vehicle. The bartender claimed he had seen nothing, but a cocktail waitress in the bar furnished identification to the officers concerning some of those responsible for the assault. The next day it was reported to officers that a member of the Hell’s Angels gang had threatened the life of this waitress as well as another woman waitress. A male witness who definitely identified five participants in the assault including the president of Vallejo Hell’s Angels and the Vallejo “Road Rats” advised officers that because of his fear of retaliation by club members he would refuse to testify to the facts he had previously furnished.

That is a representative item in the section of the report titled “Hoodlum Activities.” First, it occurred in a small town–Rodeo is on San Pablo Bay just north of Oakland–where the Angels had stopped at a bar without causing any trouble until some offense was committed against them. In this case, a driver whom even the police admit was “possibly” drunk hit one of their motorcycles. The same kind of accident happens every day all over the nation, but when it involves outlaw motorcyclists it is something else again. Instead of settling the thing with an exchange of insurance information or, at the very worst, an argument with a few blows, the Hell’s Angels beat the driver and “attempted to demolish the vehicle.” I asked one of them if the police exaggerated this aspect, and he said no, they had done the natural thing: smashed headlights, kicked in doors, broken windows and torn various components off the engine.

Of all their habits and predilections that society finds alarming, this departure from the time-honored concept of “an eye for an eye” is the one that most frightens people. The Hell’s Angels try not to do anything halfway, and anyone who deals in extremes is bound to cause trouble, whether he means to or not. This, along with a belief in total retaliation for any offense or insult, is what makes the Hell’s Angels unmanageable for the police and morbidly fascinating to the general public. Their claim that they “don’t start trouble” is probably true more often than not, but their idea of “provocation” is dangerously broad, and their biggest problem is that nobody else seems to understand it. Even dealing with them personally, on the friendliest terms, you can sense their hair-trigger readiness to retaliate.

This is a public thing, and not at all true among themselves. In a meeting, their conversation is totally frank and open. They speak to and about one another with an honesty that more civilized people couldn’t bear. At the meeting I attended (and before they realized I was a journalist) one Angel was being publicly evaluated; some members wanted him out of the club and others wanted to keep him in. It sounded like a group-therapy clinic in progress–not exactly what I expected to find when just before midnight I walked into the bar of the De Pau in one of the bleakest neighborhoods in San Francisco, near Hunters Point. By the time I parted company with them–at 6:30 the next morning after an all-night drinking bout in my apartment–I had been impressed by a lot of things, but no one thing about them was as consistently obvious as their group loyalty. This is an admirable quality, but it is also one of the things that gets them in trouble: a fellow Angel is always right when dealing with outsiders. And this sort of reasoning makes a group of “offended” Hell’s Angels nearly impossible to deal with. Here is another incident from the Attorney General’s report:

On September 19, 1964, a large group of Hell’s Angels and “Satan’s Slaves” converged on a bar in the South Gate (Los Angeles County), parking their motorcycles and cars in the street in such a fashion as to block one-half of the roadway. They told officers that three members of the club had been recently asked to stay out of the bar and that they had come to tear it down. Upon their approach the bar owner locked the doors and turned off the lights and no entrance was made, but the group did demolish a cement block fence. On arrival of the police, members of the club were lying on the sidewalk and in the street. They were asked to leave the city, which they did reluctantly. As they left, several were heard to say that they would be back and tear down the bar.

Here again is the ethic of total retaliation. If you’re “asked to stay out” of a bar, you don’t just punch the owner–you come back with your army and destroy the whole edifice. Similar incidents–along with a number of vague rape complaints–make up the bulk of the report. Eighteen incidents in four years, and none except the rape charges are more serious than cases of assaults on citizens who, for their own reasons, had become involved with the Hell’s Angels prior to the violence. I could find no cases of unwarranted attacks on wholly innocent victims. There are a few borderline cases, wherein victims of physical attacks seemed innocent, according to police and press reports, but later refused to testify for fear of “retaliation.” The report asserts very strongly that Hell’s Angels are difficult to prosecute and convict because they make a habit of threatening and intimidating witnesses. That is probably true to a certain extent, but in many cases victims have refused to testify because they were engaged in some legally dubious activity at the time of the attack.

In two of the most widely publicized incidents the prosecution would have fared better if their witnesses and victims had been intimidated into silence. One of these was the Monterey “gang rape,” and the other a “rape” in Clovis, near Fresno in the Central Valley. In the latter, a 36-year-old widow and mother of five children claimed she’d been yanked out of a bar where she was having a quiet beer with another woman, then carried to an abandoned shack behind the bar and raped repeatedly for two and a half hours by fifteen or twenty Hell’s Angels and finally robbed of $150. That’s how the story appeared in the San Francisco newspapers the next day, and it was kept alive for a few more days by the woman’s claims that she was getting phone calls threatening her life if she testified against her assailants.

Then, four days after the crime, the victim was arrested on charges of “sexual perversion.” The true story emerged, said the Clovis chief of police, when the woman was “confronted by witnesses. Our investigation shows she was not raped,” said the chief. “She participated in lewd acts in the tavern with at least three other Hell’s Angels before the owners ordered them out. She encouraged their advances in the tavern, then led them to an abandoned house in the rear… She was not robbed but, according to a woman who accompanied her, had left her house early in the evening with $5 to go bar-hopping.” That incident did not appear in the Attorney General’s report.

But it was impossible not the mention the Monterey “gang rape,” because it was the reason for the whole subject to become official. Page one of the report–which Time‘s editors apparently skipped–says that the Monterey case was dropped because “… further investigation raised questions as to whether forcible rape had been committed or if the identifications made by victims were valid.” Charges were dismissed on September 25, with the concurrence of a grand jury. The deputy District Attorney said “a doctor examined the girls and found no evidence” to support the charges. “Besides that, one girl refused to testify,” he explained, “and the other was given a lie-detector test and found to be wholly unreliable.”

This, in effect, was what the Hell’s Angels had been saying all along. Here is their version of what happened, as told by several who were there:

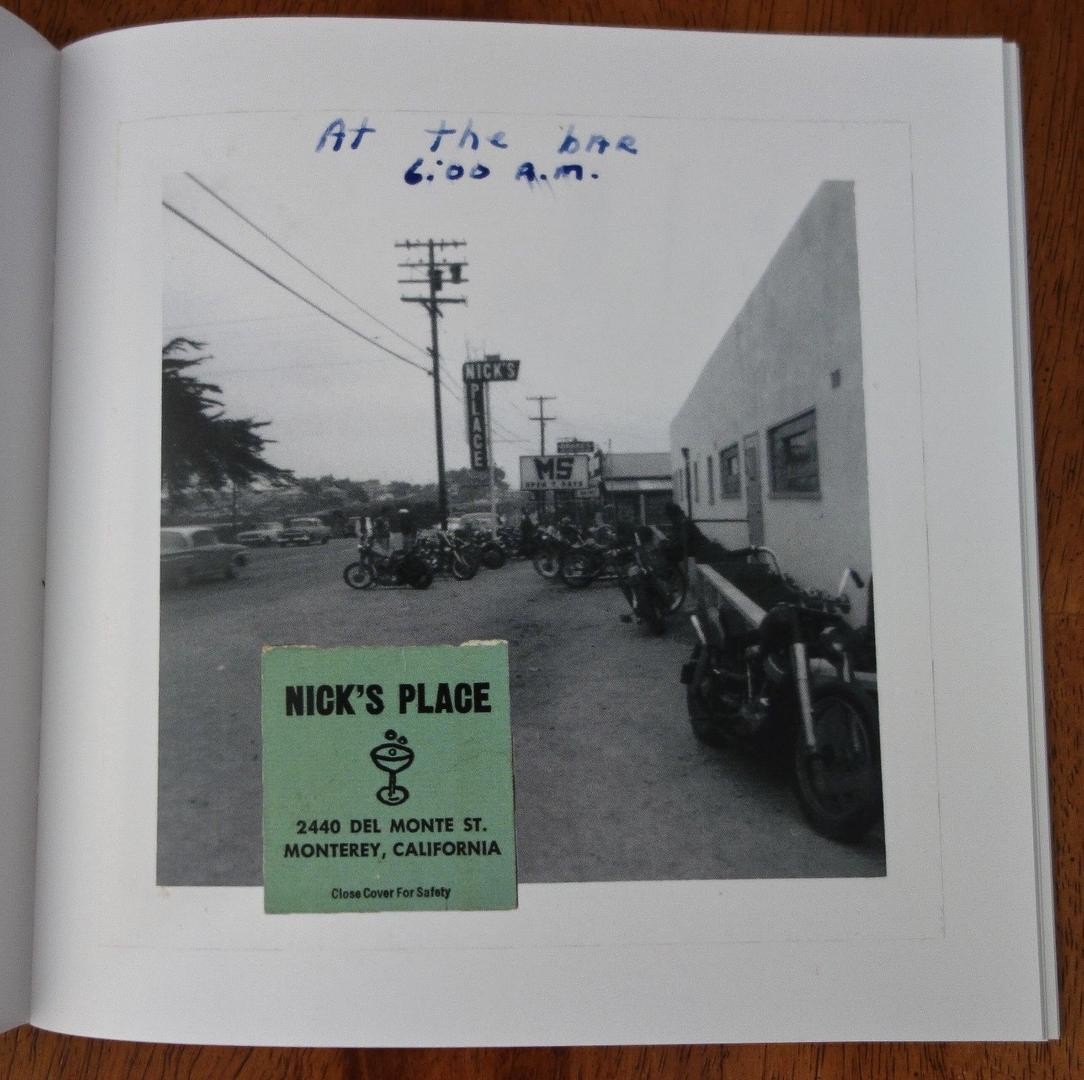

One girl was white and pregnant, the other was colored, and they were with five colored studs. They hung around our bar–Nick’s Place on Del Monte Avenue–for about three hours Saturday night, drinking and talking with our riders, then they came out to the beach with us–them and their five boyfriends. Everybody was standing around the fire, drinking wine, and some of the guys were talking to them–hustling ’em, naturally–and soon somebody asked the two chicks if they wanted to be turned on–you know, did they want to smoke some pot? They said yeah, and then they walked off with some of the guys to the dunes. The spade went with a few guys and then she wanted to quit, but the pregnant one was really hot to trot; the first four or five guys she was really dragging into her arms, but after that she cooled off, too. By this time, though, one of their boy friends had got scared and gone for the cops–and that’s all it was.

But not quite all. After that there were Senator Farr and Tom Lynch and a hundred cops and dozens of newspaper stories and articles in the national news magazine–and even this article, which is a direct result of the Monterey “gang rape.”

When the much-quoted report was released, the local press–primarily the San Francisco Chronicle, which had earlier done a long and fairly objective series on the Hell’s Angels–made a point of saying that the Monterey charges against the Hell’s Angels had been dropped for lack of evidence. Newsweek was careful not to mention Monterey at all, but the New York Times referred to it as “the alleged gang rape” which, however, left no doubt in a reader’s mind that something savage had occurred. It remained for Time, though, to flatly ignore the fact that the Monterey rape charges had been dismissed. Its article leaned heavily on the hairiest and least factual sections of the report, and ignored the rest. It said, for instance, that the Hell’s Angels initiation rite “demands that any new member bring a woman or girl [called a ‘sheep’] who is willing to submit to sexual intercourse with each member of the club.” That is untrue, although, as one Angel explained, “Now and then you get a woman who likes to cover the crowd, and hell, I’m no prude. People don’t like to think women go for that stuff, but a lot of them do.”

We were talking across a pool table about the rash of publicity and how it had affected the Angel’s activities. I was trying to explain to him that the bulk of the press in this country has such a vested interest in the status quo that it can’t afford to do much honest probing at the roots, for fear of what they might find.

“Oh, I don’t know,” he said. “Of course I don’t like to read all this bullshit because it brings the heat down on us, but since we got famous we’ve had more rich fags and sex-hungry women come looking for us that we ever had before. Hell, these days we have more action than we can handle.”

A few months later Nation published this piece by Thompson about the “outside agitator” population in Berkeley.

The term “outside agitator” was popularized during the early stages of the Civil Rights Movement when Southern law enforcement authorities and politicians discounted African-American protests as being driven by Northern white radicals, rather than being legitimate expressions of discontent. It was borrowed by Berkeley and California authorities, and used by a suspicious boarding house manager who was worried that Dustin Hoffman was one in The Graduate.

“The Nonstudent Left”

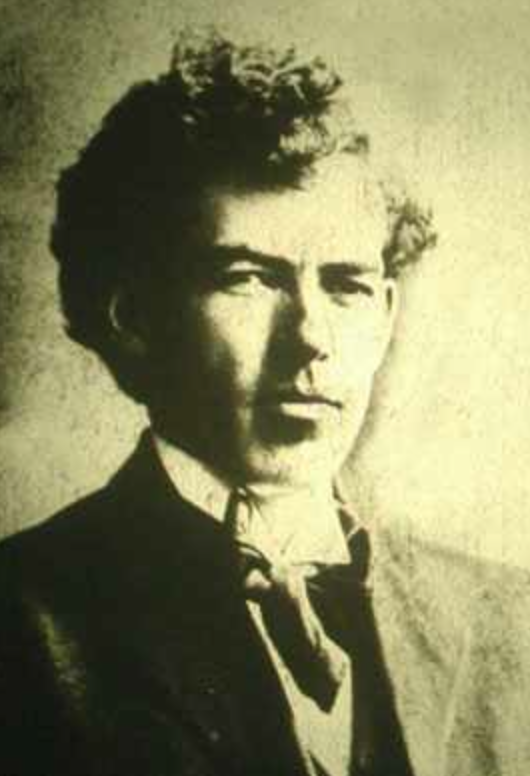

Hunter S. Thompson

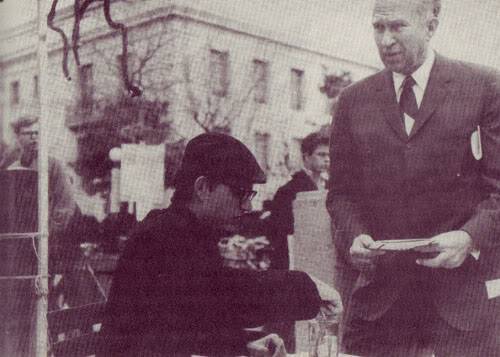

BERKELEY, September 27, 1965 — At the height of the “Berkeley insurrection” press reports were loaded with mentions of outsiders, nonstudents and professional troublemakers. Terms like “Cal’s shadow college” and “Berkeley’s hidden community” became part of the journalistic lexicon. These people, it was said, were whipping the campus into a frenzy, goading the students to revolt, harassing the administration, and all the while working for their own fiendish ends. You could almost see them loping along the midnight streets with bags of seditious leaflets, strike orders, red banners of protest and cablegrams from Moscow, Peking or Havana. As in Mississippi and South Vietnam, outside agitators were said to be stirring up the locals, who wanted only to be left alone. Something closer to the truth is beginning to emerge now, but down around the roots of the affair the fog is still pretty thick. The Sproul Hall sit-in trials ended in a series of unexpectedly harsh convictions, the Free Speech Movement has disbanded, four students have been expelled and sentenced to jail terms as a result of the “dirty word” controversy, and the principal leader, Mario Savio, has gone to England, where he’ll study and wait for word on the appeal of his four-month jail term — a procedure which may take as long as eighteen months.

As the new semester begins — with a new and inscrutable chancellor — the mood of the Berkeley campus is one of watchful baiting. The basic issues of last year are still unresolved, and a big new one has been added: Vietnam. A massive nationwide sit-in, with Berkeley as a focal point, is scheduled for October 15-16, and if that doesn’t open all the old wounds, then presumably nothing will.

For a time it looked as though Governor Edmund Brown had side-tracked any legislative investigation of the university, but late in August Assembly Speaker Jesse Unruh, an anti-Brown democrat, named himself and four colleagues to a joint legislative committee that will investigate higher education in California. Mr. Unruh told the press that “there will be no isolated investigation of student-faculty problems at Berkeley,” but in the same period he stated before a national conference of more than 1,000 state legislators, meeting in Portland, that the academic community is “probably the greatest enemy” of a state legislature.

Mr. Unruh is a sign of the times. For a while last spring he appeared to be in conflict with the normally atavistic Board of Regents, which runs the university, but somewhere along the line a blue chip compromise was reached, and whatever progressive ideas the Regents might have flirted with were lost in the summer lull. Governor Brown’s role in these negotiations has not yet been made public.

One of the realities to come out of last semester’s action is the new “anti-outsider law,” designed to keep “nonstudents” off the campus in any hour of turmoil. It was sponsored by Assemblyman Don Mulford, a Republican from Oakland, who looks and talks quite a bit like the “old” Richard Nixon. Mr. Mulford is much concerned about “subversive infiltration” on the Berkeley campus, which lies in his district. He thinks he knows that the outburst last fall was caused by New York Communists, beatnik perverts and other godless elements beyond his ken. The students themselves, he tells himself, would never have caused such a ruckus. Others in Sacramento apparently shared this view: the bill passed the Assembly by a vote of 54 to 11 and the Senate by 27 to 8. Governor Brown signed it on June 2. The Mulford proposal got a good boost, while it was still pending, when J. Edgar Hoover testified in Washington that forty-three Reds of one stripe or another were involved in the Free Speech Movement.

On hearing of this, one student grinned and said: “Well I guess that means they’ll send about 10,000 Marines out here this fall. Hell, they sent 20,000 after those fifty-eight Reds in Santa Domingo. Man, that Lyndon is nothing but hip!”

Where Mr. Hoover got his figure is a matter of speculation, but the guess in Berkeley is that it came from the San Francisco Examiner, a Hearst paper calling itself “The Monarch of the Dailies.” The Examiner is particularly influential among those who fear King George III might still be alive in Argentina.

The significance of the Mulford law lies not in what it says but in the darkness it sheds on the whole situation in Berkeley, especially on the role of nonstudents and outsiders. Who are these thugs? What manner of man would lurk on a campus for no reason but to twist student minds? As anyone who lives or works around an urban campus knows, vast numbers of students are already more radical than any Red Mr. Hoover could name. Beyond that, the nonstudents and outsiders California has legislated against are in the main ex-students, graduates, would-be transfers, and other young activist types who differ from radical students only in that they don’t carry university registration cards. On any urban campus the nonstudent is an old and dishonored tradition. Every big city school has its fringe element: Harvard, New York University, Chicago, the Sorbonne,Berkeley, the University of Caracas. A dynamic university in a modern population centre simply can’t be isolated from the realities, human or otherwise, that surround it. Mr. Mulford would make an island out of the Berkeley campus but, alas, there are too many guerillas.

In 1958, I drifted north from Kentucky and became a nonstudent at Columbia. I signed up for two courses and am still getting bills for the tuition. My home was a $12-a-week room in an off-campus building full of jazz musicians, shoplifters, mainliners, screaming poets and sex-addicts of every description. It was a good life. I used the university facilities and at one point was hired to stand in a booth all day for two days, collecting registration fees. Twice I walked almost the entire length of the campus at night with a wooden box containing nearly $15,000. It was a wild feeling and I’m still not sure why I took the money to the bursar.

Being a “non” or “nco” student on an urban campus is not only simple but natural for anyone who is young, bright and convinced that the major he’s after is not on the list. Any list. A serious nonstudent is his own guidance counselor. The surprising thing is that so few people beyond the campus know this is going on.

The nonstudent tradition seems to date from the end of World War II. Before that it was a more individual thing. A professor at Columbia told me that the late R.P. Blackmur, one of the most academic and sholarly of literary critics, got most of his education by sitting in on classes at Harvard.

In the age of Eisenhower and Kerouac, the nonstudent went about stealing his education as quietly as possible. It never occurred to him to jump into campus politics; that was part of the game he had already quit. But then the decade ended. Nixon went down, and the civil rights struggle broke out. With this, a whole army of guilt-crippled Eisenhower deserters found the war they had almost given up hoping for. With Kennedy at the helm, politics had become respectable for a change, and students who had sneered at the idea of voting found themselves joining the Peace Corps or standing on picket lines. Student radicals today may call Kennedy a phony liberal and a glamorous sellout, but only the very young will deny that it was Kennedy who got them excited enough to want to change the American reality, instead of just quitting it. Today’s activist student or nonstudent talks about Kerouac as the hipsters of the ’50s talked about Hemingway. He was a quitter, they say; he had good instincts and a good ear for the sadness of his time, but his talent soured instead of growing. The new campus radical has a cause, a multipronged attack on as many fronts as necessary: if not civil rights, then foreign policy or structural deprivation in domestic poverty pockets. Injustice is the demon, and the idea is to bust it.

What Mulford’s law will do to change this situation is not clear. The language of the bill leaves no doubt that it shall henceforth be a misdemeanor for any nonstudent or nonemployee to remain on a state university of state college campus after he or she has been ordered to leave, if it “reasonably appears” to the chief administrative officer or the person designated by him to keep order on the campus “that such person is committing an act likely to interfere with the peaceful conduct of the campus.”

In anything short of roit conditions, the real victims of Mulford’s law will be the luckless flunkies appointed to enforce it. The mind of man could devise few tasks more hopeless than rushing around this 1,000-acre, 27,000-student campus in the midst of some crowded action, trying to apprehend and remove — on sight and before he can flee — any person who is not a Cal student and is not eligible for readmission. It would be a nightmare of lies, false seizures, double entries and certain provocation. Meanwhile, most of those responsible for the action would be going about their business in legal peace. If pure justice prevailed in this world, Don Mulford would be appointed to keep order and bag subversives at the next campus demonstrations.

There are those who seem surprised that a defective rattrap like the Mulford law could be endorsed by the legislature of a supposedly progressive, enlightened state. But these same people were surprised when Proposition14, which reopened the door to racial discrimination in housing, was endorsed by the electorate last November by a margin of nearly 2 to 1.

Meanwhile, the nonstudent in Berkeley is part of the scene, a fact of life. The university estimates that about 3,000 nonstudents use the campus in various ways: working in the library with borrowed registration cards; attending lectures, concerts and student films; finding jobs and apartments via secondhand access to university listings; eating in the cafeteria, and monitoring classes. In appearance they are indistinguishable from students. Berkeley is full of wild-looking graduate students, bearded professors and long-haired English majors who looke like Joan Baez.

Until recently there was no mention of nonstudents in campus politics, but at the beginning of the Free Speech rebellion President Kerr said “nonstudent elements were partly responsible for the demonstration.”

Since then, he has backed away from that stand, leaving it to the lawmakers. Even its goats and enemies now admit that the FSM revolt was the work of actual students. It has been a difficult fact for some people to accept, but a reliable poll of student attitudes at the time showed that roughly 18,000 of them supported the goals of the FSM, and about half defy the administration, the Governor and the police, rather than back down. The faculty supported the FSM by close to 8 to 1. The nonstudents nearly all sided with the FSM. The percentage of radicals among them is much higher than among students. It is invariably the radicals, not the conservatives, who drop out of school and become activist nonstudents. But against this background, their attitude hardly matters.

“We don’t play a big role politically,” says one. “But philosophically we’re a hell of a threat to the establishment. Just the fact that we exist proves that dropping out of school isn’t the end of the world. Another important thing is that we’re not looked down on by students. We’re respectable. A lot of students I know are thinking of becoming nonstudents.”

“As a nonstudent I have nothing to lose,” said another. “I can work full time on whatever I want, study what interests me, and figure out what’s really happening in the world. That student routine is a drag. Until I quit the grind I didn’t realize how many groovy things there are to do around Berkeley: concerts, films, good speakers, parties, pot, politics, women — I can’t think of a better way to live, can you?”

Not all nonstudents worry the lawmakers and administrators. Some are fraternity bums ho flunked out of the university, but don’t want to leave the parties and the good atmosphere. Others are quiet squares or technical types, earning money between enrollments and meanwhile living nearby. But there is no longer the sharp division that used to exist between the beatnik and the square: too many radicals wear ties and sport coats; too many engineering students wear boots and levis. Some of the most bohemian-looking girls around the campus are Left-puritans, while some of the sweetest-looking sorority types are confirmed pot smokers and wear diaphragms on all occasions.

Nonstudents lump one another — and many students – into two very broad groups: “political radicals” and “social radicals.” Again, the division is not sharp, but in general, and with a few bizarre exceptions, a political radical is a Left activist in one or more causes. His views are revolutionary in the sense that his idea of “democratic solutions” alarms even the liberals. He may be a Young Trotskyist, a Du Bois Club organizer or merely and ex-Young Democrat, who despairs of President Johnson and is now looking for action with some friends in the Progressive Labor Party.

Social radicals tend to be “arty.” Their gigs are poetry and folk music, rather than politics, although many are fervently committed to the civil rights movement. Their political bent is Left, but their real interests are writing, painting, good sex, good sounds and free marijuana. The realities of politics puts them off, although they don’t mind lending their talents to a demonstration here and there, or even getting arrested for a good cause. They have quit one system and they don’t want to be organized into another; they feel they have more important things to do.

A report last spring by the faculty’s Select Committee on Education tried to put it all in a nutshell: “A significant and growing minority of students is simply not propelled by what we have come to regard as conventional motivation. Rather than aiming to be successful men in an achievement-oriented society, they want to be moral men in a moral society. They want to lead lives less tied to financial return than to social awareness and responsibility.”

The committee was severely critical of the whole university structure, saying: “The atmosphere of the campus now suggests too much an intricate system of compulsions, rewards and punishments; too much of our attention is given to score keeping.” Among other failures, the university was accused of ignoring “the moral revolution of the young.”

Talk like this strikes the radicals among “the young” as paternalistic jargon, but they appreciate the old folks’ sympathy. To them, anyone who takes part in “the system” is a hypocrite. This is especially true among the Marxist, Mao-Castro element — the hipsters of the Left.

One of these is Steve DeCanio, a 22-year-old Berkeley radical and Cal graduate in math, now facing a two-month jail term as a result of the Sproul Hall sit-ins. He is doing graduate work, and therefore immune to the Mulford law. “I became a radical after the 1962 auto row (civil rights) demonstrations in San Francisco,” he says. “That’s when I saw the power structure and understood the hopelessness of trying to be a liberal. After I got arrested I dropped the pre-med course I’d started at San Francisco State. The worst of it, though, was being screwed time and again in the courts. I’m out on appeal now with four and a half months of jail hanging over me.”

DeCanio is an editor of Spider, a wild-eyed new magazine with a circulation of about 2,000 on and around the Berkeley campus. Once banned, it thrived on the publicity and is now officially ignored by the protest-weary administration. The eight-manned editorial board is comprised of four students and four nonstudents. The magazine is dedicated, they say, to “sex, politics, international communism, drugs, extremism and rock’n’roll.” Hence, S-P-I-D-E-R.

DeCanio is about two thirds political radical and one-third social. He is a bright, small, with dark hair and glasses, clean-shaven, and casually but not sloppily dressed. He listens carefully to questions, uses his hands for emphasis when he talks, and quietly says things like: “What this country needs is a revolution; the society is so sick, so reactionary, that it just doesn’t make sense to take part in it.”

He lives, with three other nonstudents and two students, in a comfortable house on College Avenue, a few blocks from campus. The $120-a-month rent is split six ways. There are three bedrooms, a kitchen and a big living room with a fireplace. Papers litter the floor, the phone rings continually, and people stop by to borrow things: a pretty blonde wants a Soviet army chorus record, a Tony Perkins type from the Oakland Du Bois Club wants a film projector; Art Goldberg — the arch-activist who also lives here — comes storming in, shouting for help on the “Vietnam Days” teach-in arrangements.

It is all very friendly and collegiate. People wear plaid shirts and khaki pants, white socks and mocasins. There are books on the shelves, cans of beer and Cokes in the refrigerator, and a manually operated light bulb in the bathroom. In the midst of all this it is weird to hear people talking about “bringing the ruling class to their knees,” or “finding acceptable synonyms for Marxist terms”.

Political conversation in this house would drive Don Mulford right over the wall. There are riffs of absurdity and mad humor in it, but the base line remains a dead-serious alienation from the “Repugnant Society” of 20th-century America. You hear the same talk on the streets, in coffee bars, on the walk near Ludwig’s Fountain in front of Sproul Hall, and in other houses where activists live and gather. And why not? This is Berkeley, which DeCanio calls “the center of West Coast radicalism.” It has a long history of erratic politics, both on and off the campus. From 1911 to 1913, its Mayor was a Socialist named Stitt Wilson. It has more psychiatrists and fewer bars than any other city of comparable size in California. And there are 249 churches for 120,300 people, of which 25 percent are Negroes — one of the highest percentages of any city outside the South.

Culturally, Berkeley is dominated by two factors: the campus and San Francisco across the Bay. The campus is so much a part of the community that the employment and housing markets have long since adjusted to student patterns. A $100-a-month apartment or cottage is no problem when four or five people split the rent, and there are plenty of ill-paid, minimum-strain jobs for those without money from home. Tutoring, typing, clerking,car washing, hash slinging and baby sitting are all easy ways to make a subsistence income; one of the favorites among nonstudents is computer programming, which pays well.

Therefore, Berkeley’s nonstudents have no trouble getting by. The climate is easy, the people are congenial, and the action never dies. Jim Prickett, who quit the University of Oklahoma and flunked out of San Francisco State, is another of Spider’s nonstudent editors. “State has no community,” he says, “and the only other nonstudent I know of at Oklahoma is now in jail.” Prickett came to Berkeley because “things are happening here.” At 23, he is about as far Left as a man can get in these times, but his revolutionary zeal is gimped by pessimism. “If we have a revolution in this country it will be a Fascist take-over,” he says with a shrug. Meanwhile he earns $25 a week as Spider’s star writer, smiting the establishment hip and thigh at every opportunity. Prickett looks as much like a Red menace as Will Rogers looked like a Bantu. He is tall, thin, blond, ans shuffles. “Hell, I’ll probably sell out,” he says with a faint smile. “Be a history teacher or something. But not for a while.”

Yet there is something about Prickett that suggests he won’t sell out so easily. Unlike many nonstudent activists, he has no degree, and in the society that appalls him even a sellout needs credentials. That is one of the most tangible realities of the nonstudent; by quitting school he has taken a physical step outside the system — a move that more and more students seem to find admirable. It is not an easy thing to repudiate — not now, at any rate, while the tide is running that way. And “the system” cannot be rejoined without some painful self-realization. Many a man has whipped up a hell of a broth of reasons to justify his sellout, but few recommend the taste of it.

The problem is not like that of high school dropouts. They are supposedly inadequate, but the activist nonstudent is generally said to be superior. “A lot of these kids are top students,” says Dr. David Powellson, chief of Cal’s student psychiatric clinic, “but no university is set up to handle them.”

How, then, are these bright mavericks to fit into the superbureaucracies of government and big business? Cal takes its undergraduates from the top eighth of the state’s high school graduates, and those accepted from out of state are no less “promising.” The ones who migrate back to Berkeley after quitting other schools are usually the same type. They are seekers — disturbed, perhaps, and perhaps for good reason. Many drift from one university to another, looking for the right program, the right professor, the right atmosphere, and right way to deal with the deplorable world they have suddenly grown into. It is like an army of Holden Caulfields, looking for a home and beginning to suspect they may never find one.

These are the outsiders, the nonstudents, and the potential — if not professional — troublemakers. There is something primitive and tragic in California’s effort to make a law against them. The law itself is relatively unimportant, but the thinking that conceived it is a strutting example of what the crisis is all about. A society that will legislate against its unfulfilled children and its angry, half-desperate truth seekers is bound to be shaken as it goes about making a reality of mass education.

It is a race against time, complacency and vested interests. For the Left-activist nonstudent the race is very personal. Whether he is right, wrong, ignorant, vicious, super-intelligent or simply bored, once he has committed himself to the extent of dropping out of school, he has also committed himself to “making it” outside the framework of whatever he has quit. A social radical presumably has his talent, his private madness or some other insulated gimmick, but for the political radical the only true hope is somehow to bust the system that drove him into limbo. In this new era many believe they can do it, but most of those I talked to at Berkeley seemed a bit nervous. There was a singular vagueness as to the mechanics of the act, no real sense of the openings.

“What are you doing in ten years from now?” I asked a visiting radical in the house where Spider is put together. “What if there’s no revolution by then, and no prospects of one?”

“Hell,” he said. “I don’t think about that. Too much is happening right now. If the revolution’s coming, it had better come damn quick.”

The Nation, vol. 201, September 27, 1965