Barbara Garson came to Berkeley from New York in 1962. She was ours for seven years. She left with fame in her pocket as a result of the success of her satirical play MacBird. This is an review of those seven years.

There is nothing quirky about this story, not the usual fare. But – it is all about Berkeley in another time, a time that still informs who we are today. It is a time that is rejected as irrelevant by some today, but I think that history will absolve those of us who find our past relevant and inspiring – la historia nos absolvera. There are lessons to be learned here, values to be absorbed, stories to remember. Yes, it’s my Berkeley y’all!

Garson and her then-husband honeymooned in Cuba after the triumph of the revolution in January 1959.

Richard Gibson, left, and Robert Taber, right, (Credit: Richard Gibson Papers, George Washington University)

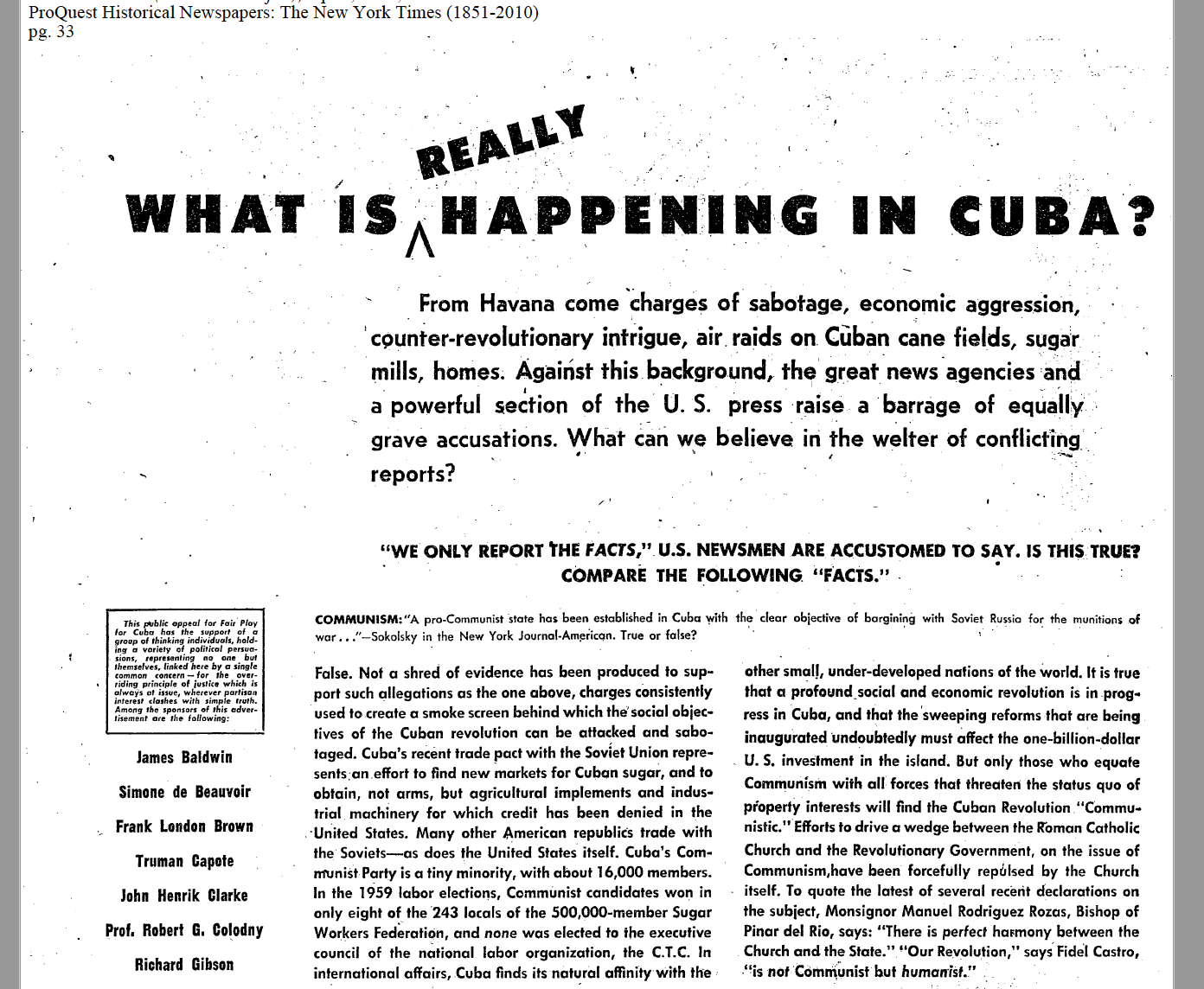

In April 1960, two CBS reporters, Robert Taber and Richard Gibson, ran a full-page ad in the New York Times stating the importance of the Cuban revolution. The authors received more than a thousand letters from people ready to take action.

As a result, the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC) was established. The main objective of the FPCC was for the United States to end its economic boycott of Cuba. A decent number of celebrities joined or supported the FPPC. It is today perhaps best known because of Lee Harvey Oswald’s involvement, but that is a rabbit hole that need not be explored here.

On April 27, 1961, J. Edgar Hoover ordered FBI agents to focus on pro-Castro activists because the FPCC illustrated “the capacity … to mobilize its efforts in such a situation so as to arrange demonstrations and influence public opinion.”

The FBI launched a red-baiting campaign against the FPCC during May 1961. According to civil rights attorney Bill Simpich, the FBI “developed a Mass Media Program that included over 300 newspaper reporters, columnists, radio commentators, and television news investigators.” It worked. For example, the Newspaper Enterprise Association’s widely syndicated columnist Peter Edson described the Fair Play for Cuba Committee in his column as consisting of “a sorry cast of characters with amazing backgrounds.”

Garson was a member of that sorry cast – she supported the FPCC.

Garson supported the goals but wasn’t naive – she saw the FPPC as a front for the Young Socialist Alliance, a Trotskyist youth group of the Socialist Workers Party. At its zenith, the YSA had 1,434 members.

When she and her then-husband arrived in Berkeley, they had seen Operation Abolition.

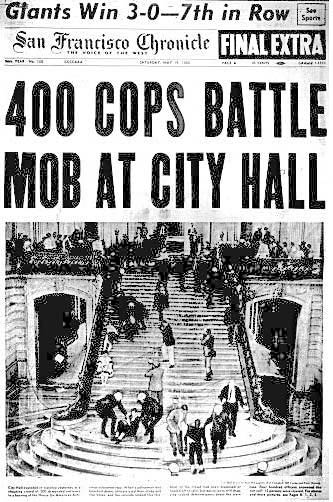

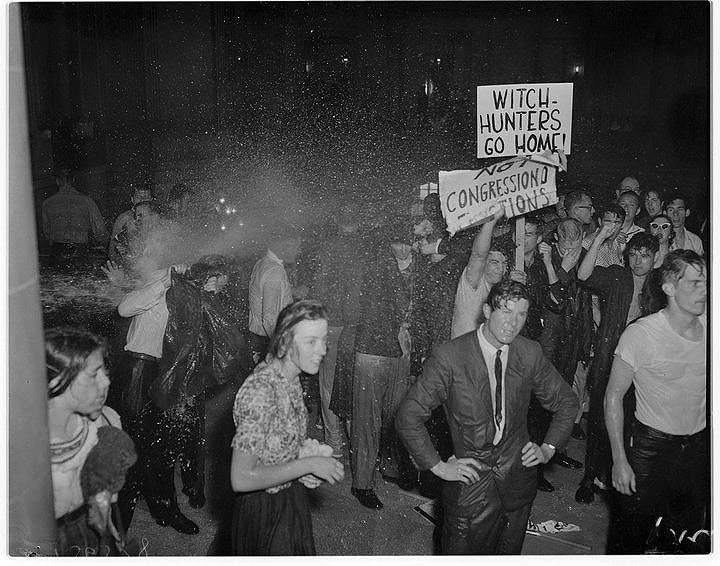

The House Un-American Activities Commission produced Operation Abolition in an attempt to discredit the protestors at the HUAC hearings in San Francisco in May, 1960.

Protestors, many from Berkeley, challenged HUAC’s attack on teachers. When the Committee denied the protesters entrance to the hearings, the police attacked and swept them out of the San Francisco City Hall rotunda with fire hoses – a tactic that Birmingham’s police chief would use three years later. It all started here! There were 64 arrests.

“Operation Abolition” was shown around the country during 1960 and 1961. It was clumsy propaganda at best and it did more to build the young Movement than to demonize it as Communist-inspired.

Berkeley became a beacon and a magnet, the place to inspire and the place to go for young people feeling the awakening of the political forces that would shape the 60s. It was a draw for Garson, and it was a draw for others.

When Garson and her then-husband arrived in Berkeley, YSAers Jim and Betty Petras met them at the airport and put them up. Garson: “We soon joined the YSA. Though I quit the group after only a year, I remain ‘some kind of socialist.’ The YSAers were the first Socialists I’d ever met and despite the annoying sectarianism, it wasn’t a waste to get a basic socialist education.”

During the tense days of the Cuban missile crisis, the local FBI office engaged in pervasive surveillance every known leftist in Berkeley, including the Petras/Garson household. Frustrated by the constant presence of two men parked across the street, someone in the apartment called the Berkeley Police and told the police that there were two men in a car parked on the street calling to every young boy who walked by and were talking with them.

The Berkeley Police Department was no slouch. There was a near-instant response and they confronted the FBI surveillance team. Good clean fun!

Garson enrolled at Cal with a major in history, focusing on classical history. She earned her B.A. in 1964.

Swept up by the many political groups in Berkeley, she dropped out of the Young Socialist Alliance.

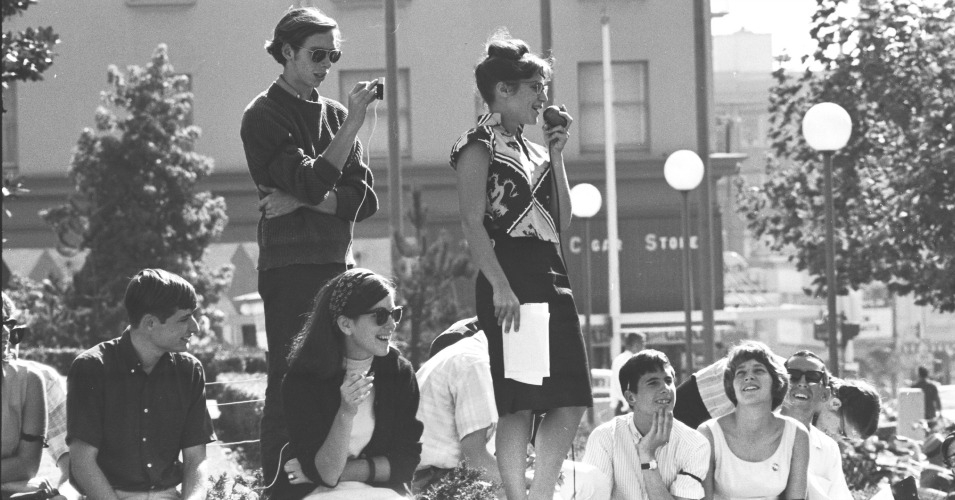

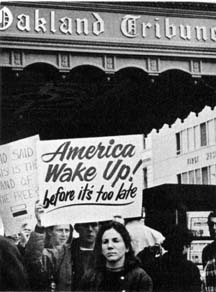

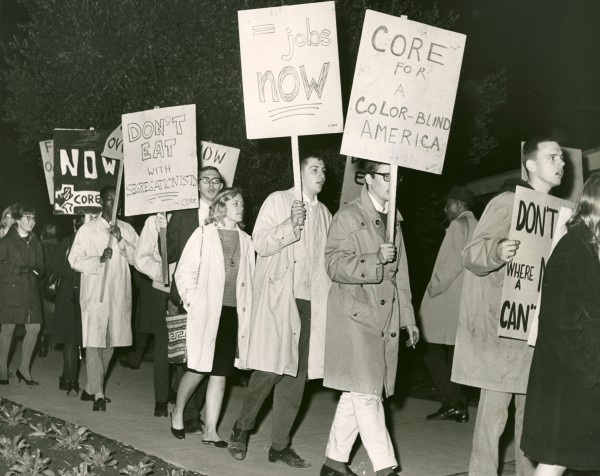

She says “I got to know San Francisco through demonstrations.” In 1960, grass roots black organizations and students from U.C. Berkeley’s CORE Chapter began to pressure local Bay Area companies to hire more minority employees. Their tactics were based on those of the southern Civil Rights Movement – well-coordinated non-violent protests paired with an offer of negotiations over jobs.

Beginning in late 1963, Berkeley students conducted marches in Oakland, San Francisco, Berkeley, and Richmond. Garson was very involved.

And then came the Free Speech Movement.

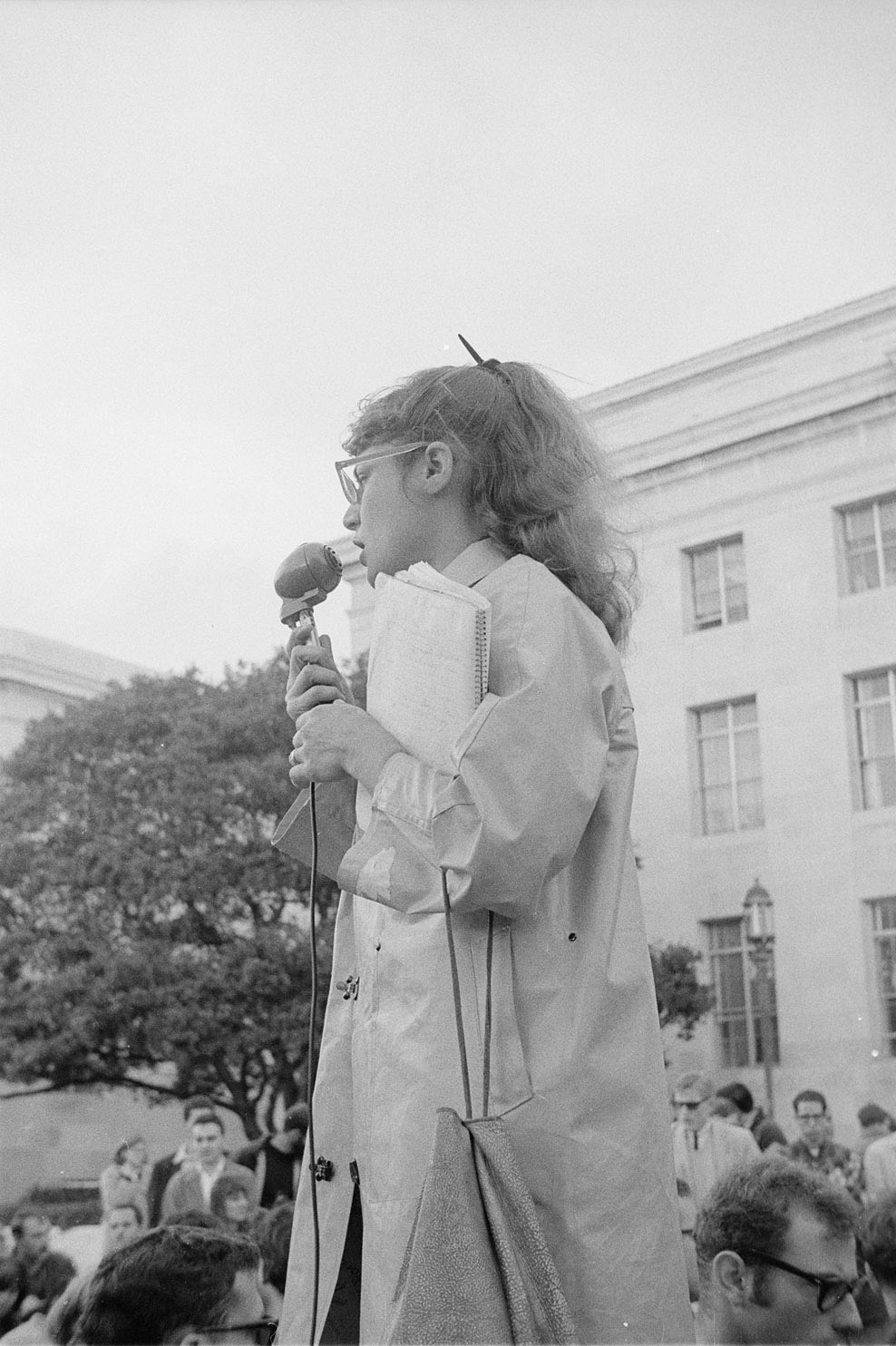

Garson was All In. She demonstrated. She went to meetings. She spoke. She edited the Free Speech Newsletter. She worked with David Lance Goines and others printing it.

On December 4, 1964, Garson was arrested as part of the Sproul Hall sit-in. With her was her good friend Anita Medal. Medal came to Cal in 1960 and had stayed fairly apolitical under the summer of 1963.

The murder of civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney made the work that CORE was doing in the Bay Area real and important. Early on, Garson would explain the Movement acronyms to Medal.

Civil rights protestors in front of Sea Wolf Restaurant in Oakland, California. February 5, 1965. Don Mohr, photographer. Gelatin silver print. Collection of Oakland Museum of California. The Oakland Tribune Collection. Gift of ANG Newspapers.

They co-chaired CORE’s restaurant project.

On December 4th they found themselves arrested at Sproul Hall with 800 other FSM supporters and were locked up at Santa Rita together. Anita remembers Garson’s arrest this way: “We were seated. A cop was hovering over Barbara’s husband Marvin arresting him when Barbara jumped onto the cop’s back!”

Garson remembers and amplifies: “My hours in Sproul Hall were generally peaceful and indeed pleasant. My ultimate arrest for trespassing was by a Berkeley cop who treated me politely. Yet, in addition to trespassing, I was charged with assaulting an officer. This is how it happened. There was a black young man named Hilbert J. Coleman [thanks to Barbara Stack for the full name) who hung around campus and participated in the sit-in. At one point he climbed on the card catalogue/tables in the hallway to lead cheers. After a few minutes several cops grabbed him down. My husband Marvin jumped up as if to defend Hilbert and the cops pulled Marvin onto the floor and surrounded him. I jumped up instinctively and shoved through that circle of cops to see what was happening to Marvin. To get through that solid circle of blue (or was it gray or brown?) I punched one of the cops on the shoulder. Though I punched with all my might there was a long delay until one of the cops said ‘Hey, she hit me.'”

Garson explains what happened at Santa Rita with her and Medal: “The courts set million-dollar appeal bail bonds for the FSM supporters after they were convicted.

“To test the legality of such high bails for first offense trespassing, Antia Medal and I went directly to jail to force a quick habeas corpus decision. We lost the case.

“But we were having so much fun in Santa Rita prison that we both decided to stay and serve out our full sentences right then rather than appeal or pay fines. It was such a relief. It was wonderful. There was somebody taking care of you. You had free time, no schedule, no work. It was a holiday. It was better than life at home.”

“But we were having so much fun in Santa Rita prison that we both decided to stay and serve out our full sentences right then rather than appeal or pay fines. It was such a relief. It was wonderful. There was somebody taking care of you. You had free time, no schedule, no work. It was a holiday. It was better than life at home.”

The caption above refers to Anita Medal’s cats-eye glasses. They have an upsweep at the outer edges where the temples or arms join the frame front. They were mainly popular in the 1950s and 1960s among women and are often associated with the Beehive hairstyle and other looks of the period.

After very long days working on the newsletter and picketing, Garson wrote letters. They are detailed and exceed the patience of the casual reader. If you want to read them, click on the button.

After it all, Garson had good things and bad things to say about the FSM.

The good: “The spirit of solidarity was great. Ten thousand supporters on Sproul Plaza would decide tactical questions in an ego-less, cooperative way. Republicans, religious groups, sororities, fraternity boys – everyone stayed together. The DuBois Club was very reliable, you could count on them.”

The bad: “The FSM started when powerful California businessmen pressured the University to limit our free speech on campus because we are using it to help minorities and working people off campus. But the exhausting year of fighting for our own rights diverted us from the causes we started organizing about. After the FSM many of us segued into the anti-Vietnam war movement. We didn’t know enough about economics and didn’t focus on how American working people were getting more desperate.”

The bad, more: When asked about sexism in the FSM, Garson admits that she didn’t even think about it then. She remembers being embarrassed by a few women who wanted to do laundry or feed the male leaders, but she thinks that this also embarrassed the male leaders like Jack Weinberg and Mario Savio.

And: The treatment of women within the FSM itself was not bad, but the press was bad. Newspapers, which could not shed the idea that the movement had to be leader-based, tended to male identification of active and visible women – Art Golderberg’s sister or Herbert Aptheker’s daughter or so-and-so’s wife or girlfriend.

In early 1965 came the “Filthy Speech Movement.”

Garson writes: “We had restored complete free speech and were at the height of our influence when a young man sat down on a sidewalk with a crayoned sign that said FUCK. University President Clark Kerr had him arrested then bombarded the press with reports of a new Filthy Speech Movement.”

The young man was Charles “Charlie Brown” Artman. Garson describes him as a “drifter – he wasn’t from Berkeley and none of us knew him, though he wasn’t a plant either, I don’t believe.” He was a prototype of a hippie, living in a teepee and espousing the use of drugs as a quasi-religous rite. Remember – this was 1965. If you look at what Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters looked like at the time, you will see straight-looking kids doing far out things. Brown looked far out and was doing far out things.

Some of the FSM crowd threw themselves into the new fight, most notably Art Goldberg. A total of seven were arrested and/or had university disciplinary charges filed against them. They called themselves the “Filthy Seven.”

Two of them, John Thompson and Art Goldberg, were the last people in the United States to serve jail time for obscenity.

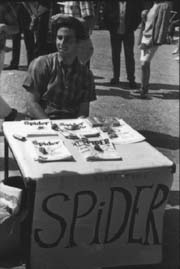

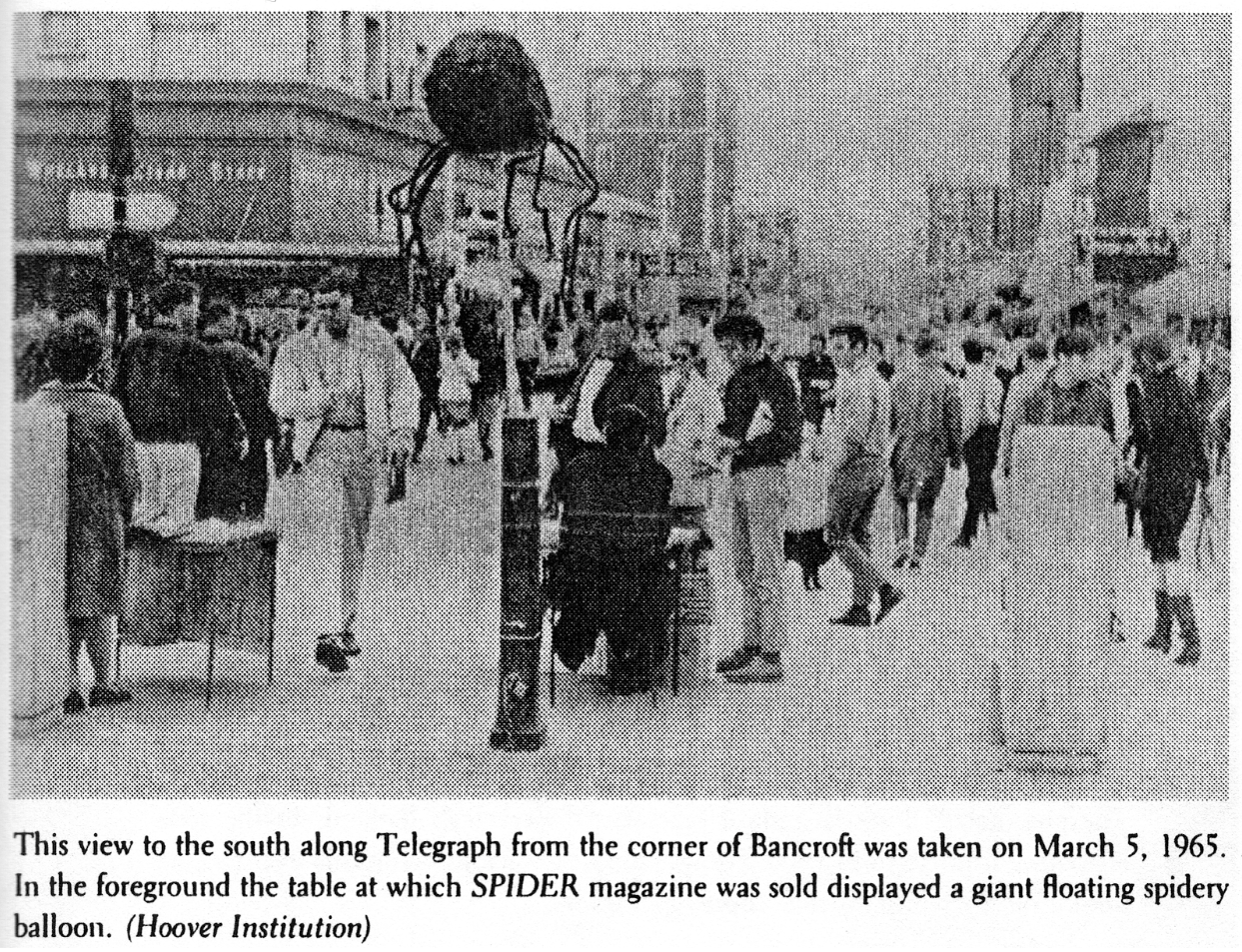

There was a more “respectable” element in Spider magazine, which lasted two issues.

Esquire magazine did an article on Spider that did miracles for sales.

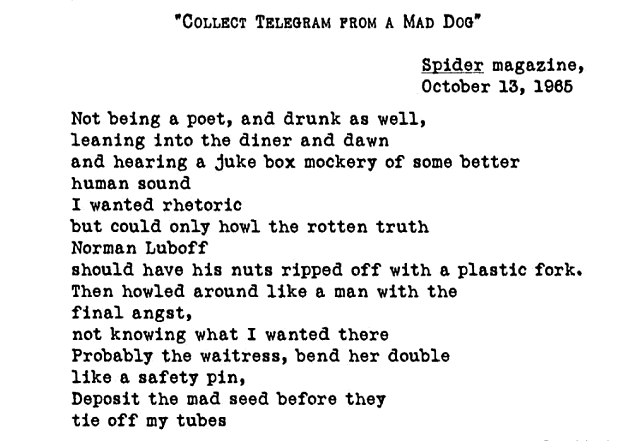

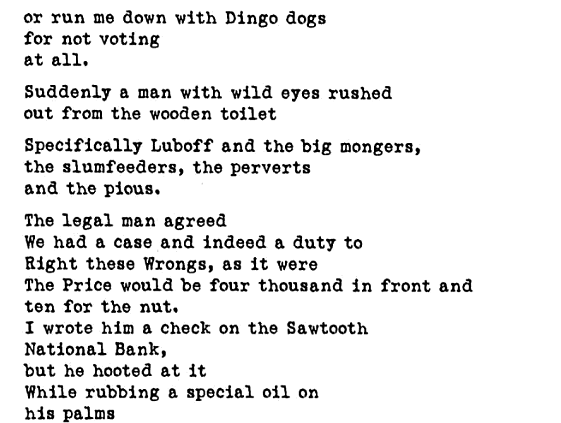

Hunter S. Thompson was living in the Bay Area at the time, and wrote several articles for The Nation about Bay Area issues, which you can find here.

Thompson published this poem in Spider:

Garson saw it all as a conundrum: “It was a terrible trap. Some felt the Free Speech Movement had to defend the arrested man. Free speech is free speech. But most believed we should let it pass. We were worried that it would obscure what we really stood for. Besides, if we entered a battle on an issue that so divided us, the FSM would be weak, giving Kerr the signal to roll back everything we’d won.”

Garson saw it all as a conundrum: “It was a terrible trap. Some felt the Free Speech Movement had to defend the arrested man. Free speech is free speech. But most believed we should let it pass. We were worried that it would obscure what we really stood for. Besides, if we entered a battle on an issue that so divided us, the FSM would be weak, giving Kerr the signal to roll back everything we’d won.”

In Garson’s eyes, this led to the dissolution of the Free Speech Movement: “I don’t think Mario cared much about the right to use four letter words. But he was distressed that we, himself included, should be making decisions based on what fights we could ‘afford’ to take on. If the FSM couldn’t afford to loose, perhaps the larger movement couldn’t afford the FSM. We must disband, we decided, and let younger people (most of us were over twenty) launch future battles unfettered. I agreed. But let me confess to more ignoble motives. We were tired: we had lived totally public lives for ten months; the private was so alluring. So for high-minded, low-minded and just pure lazy reasons, we officially disbanded the Free Speech Movement. The only structure left is a more recently formed archives and reunion committee.”

When the one-year anniversary of the Free Speech Movement rolled around in 1965, what was left of the FSM planning committee thought about an anniversary teach-in inside Sproul Hall. They asked a Dean for permission (asking for permission!) and the Dean “said that that would be like commemorating the assassination of the president by assassinating another president.” They settled for the cliched rally on the Sproul Hall steps.

Garson describes how the cliched rally turned out – a production of Mario and the Magician, no relation to the novella written by Thomas Mann in 1929. Garson’s words:

I volunteered to write a skit that turned into Mario and the Magician—a play for two crude, ten foot tall styrofoam puppets, representing Mario Savio and Clark Kerr.

The play opens with Mario proclaiming in his oft quoted words “There comes a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious…” He’s interrupted by The Clark Kerr puppet who asks what he wants. “Free Speech” Mario replies earnestly. Kerr’s answer amounts to “Calm down. I can get it for you wholesale.”

There follows a five-minute round of committees and compromises that duplicates our year of negotiating with administrators who never intended to offer us anything. Finally Savio realizes he’s been had and begins again “There comes a time when the operation of the machine become so odious, makes you so sick at heart.”

Up till then the voices had been played by FSMer Barry Melton. But at this point we switch to a tape of Mario’s himself completing the speech he gave before

We went into the building. It’s followed by the ethereal voice of Joan Baez singing “How many Roads Must a Man Walk Down,” as I remembered it that day. (Others remember her singing “We Shall Not Be Moved.”)

The FSM didn’t do counts of the audiences at our regular campus rallies on the Sproul Hall Steps but we had standard estimates based on how far into the plaza the crowd extended . This was what we called a 5,000 crowd.

Before Mario and the Magician started I told about a dozen people in the front row that at the end of the skit the Mario puppet would walk toward the doors of Sproul Hall. I asked if they would please follow it to give the rest of the audience the effect of a procession into the building. I swear that’s all I intended.

But my first dramatic effort wound up with a cast of thousands as the entire audience moved, row by row, into the building, up the stairs, across the second floor hallway then back down the opposite stairway and out of the building.

Garson was stunned by the response. “I’ve never had another theatrical success like that. Indeed I’ve never had another moment of power and glory like that in all my life. The drama worked because I knew the crowd, and we knew ourselves. No matter what the newspapers wrote about ‘Berkeley Rebels,’ we FSMers were as naïve as that awkward Styrofoam puppet. Yes, some of us had been to places where civil rights workers and grape strikers were arrested, beaten and even killed. But we still couldn’t believe that our own university officials would try to deceive and actually lie to us. Being lied to by those folks in locus parentis was the most radicalizing thing that happened to most students on the Berkeley campus that year. It’s what motivated us back into action, time and again. We grew older, but not wiser enough, thank goodness, to give up our efforts to change the world.”

For the next year, Garson withdrew somewhat from the fray.

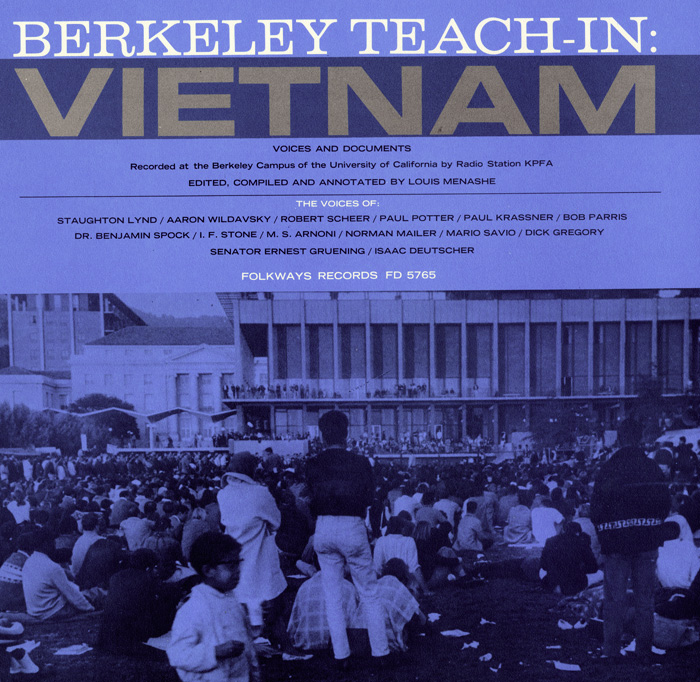

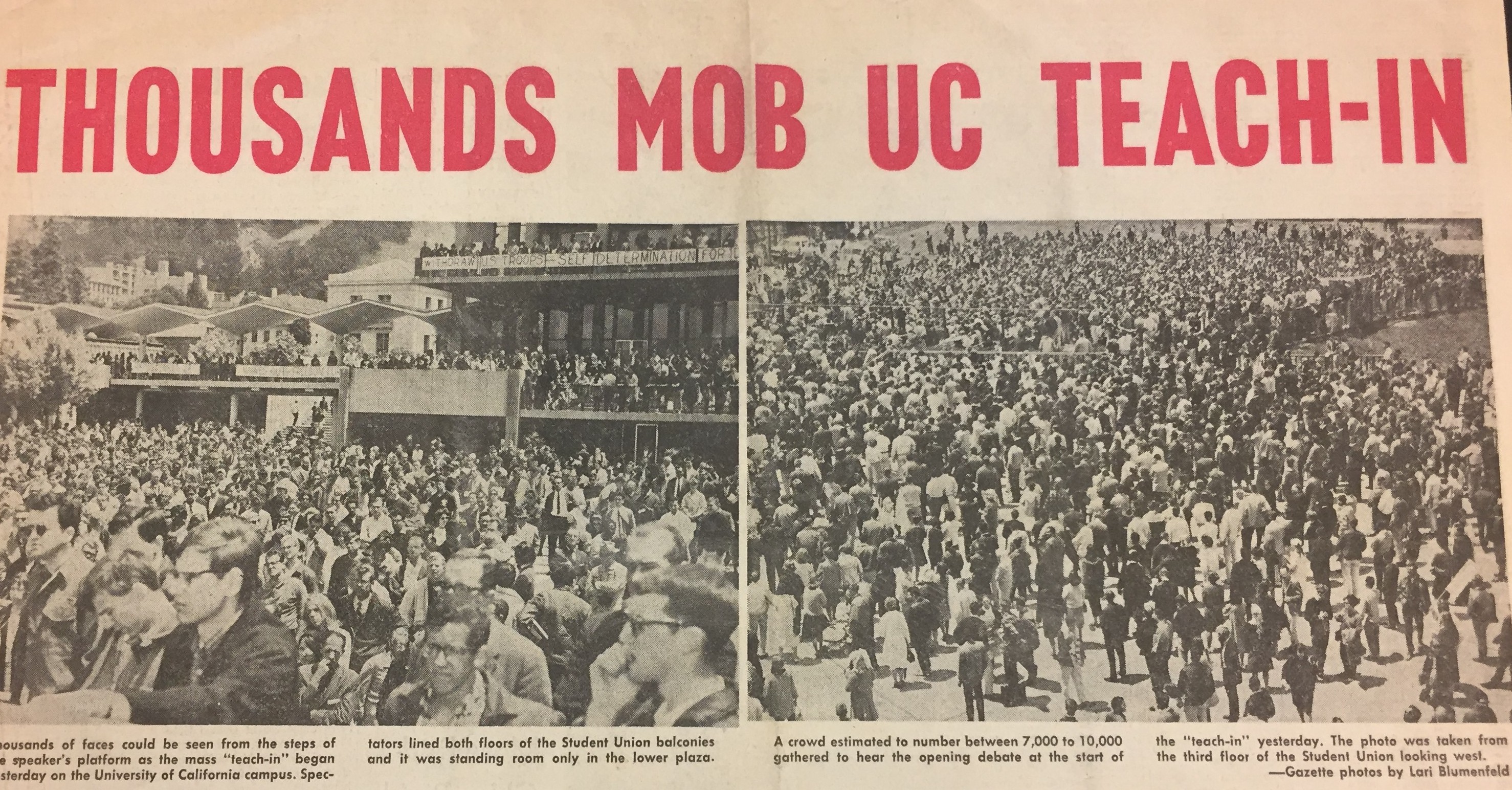

She and about 30,000 others participated in the Vietnam Day Committee’s 36-hour teach-in on May 21-23, Dr. Benjamin Spock, Norman Mailer, Norman Thomas, Alan Watts,Bob Moses, Dick Gregory,Mario Savio, Phil Ochs, and I.F. Stone were among the well-known who spoke. If you click on the album cover above you can hear many of the speeches.

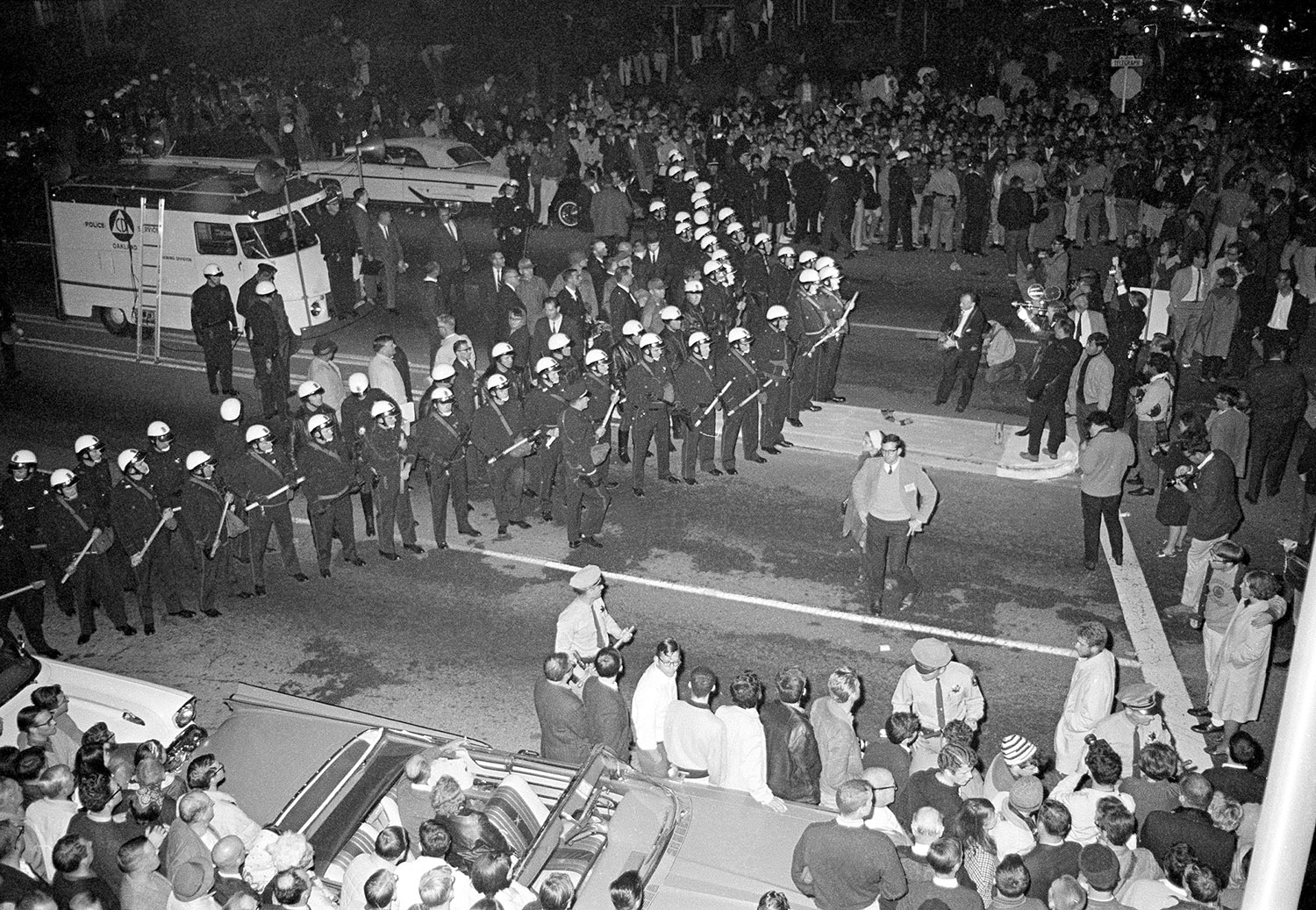

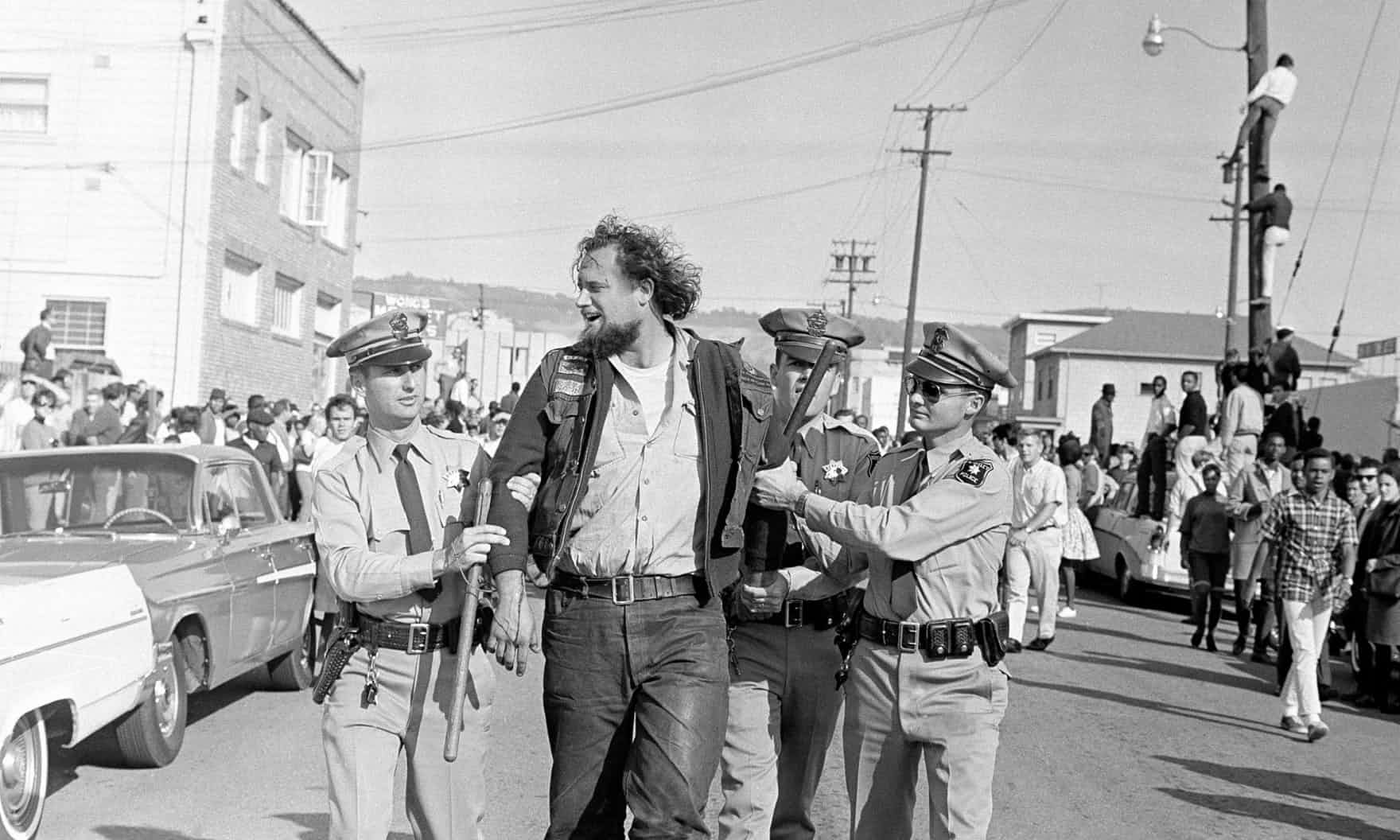

In October 1967, Garson took part in a VDC march from Berkeley to – it planned – the Army Induction Center in Oakland. Oakland police formed a line at the Berkeley-Oakland border and refused to let the Berkeley marchers enter Oakland.

Garson: “I was up front, near the Oakland border. There were two lines – the Berkeley Police and the Oakland Police. The Hells Angels were behind the Oakland Police, trying to get at the demonstrators. The Oakland police allowed the Hells Angeles to saunter into the no-man’s land towards the demonstrators. Our lawyer, Bob Treuhaft, asked Oakland Police Chief Charles Gaines to control the Hells Angels. Gaines answered, ‘They have their constitutional rights.'” Really????

When the Angels crossed into Berkeley swinging, the protestors spontaneously sat down on the street, leaving the the Hells Angels standing exposed. “You could see that we weren’t doing anything, it was the Hells Angels. The Oakland cops wanted a brawl and we wouldn’t give them one. It was the Berkeley Police who subdued the Hells Angeles, one of whom broke the leg of a Berkeley cop. We sent him cards in the hospital.”

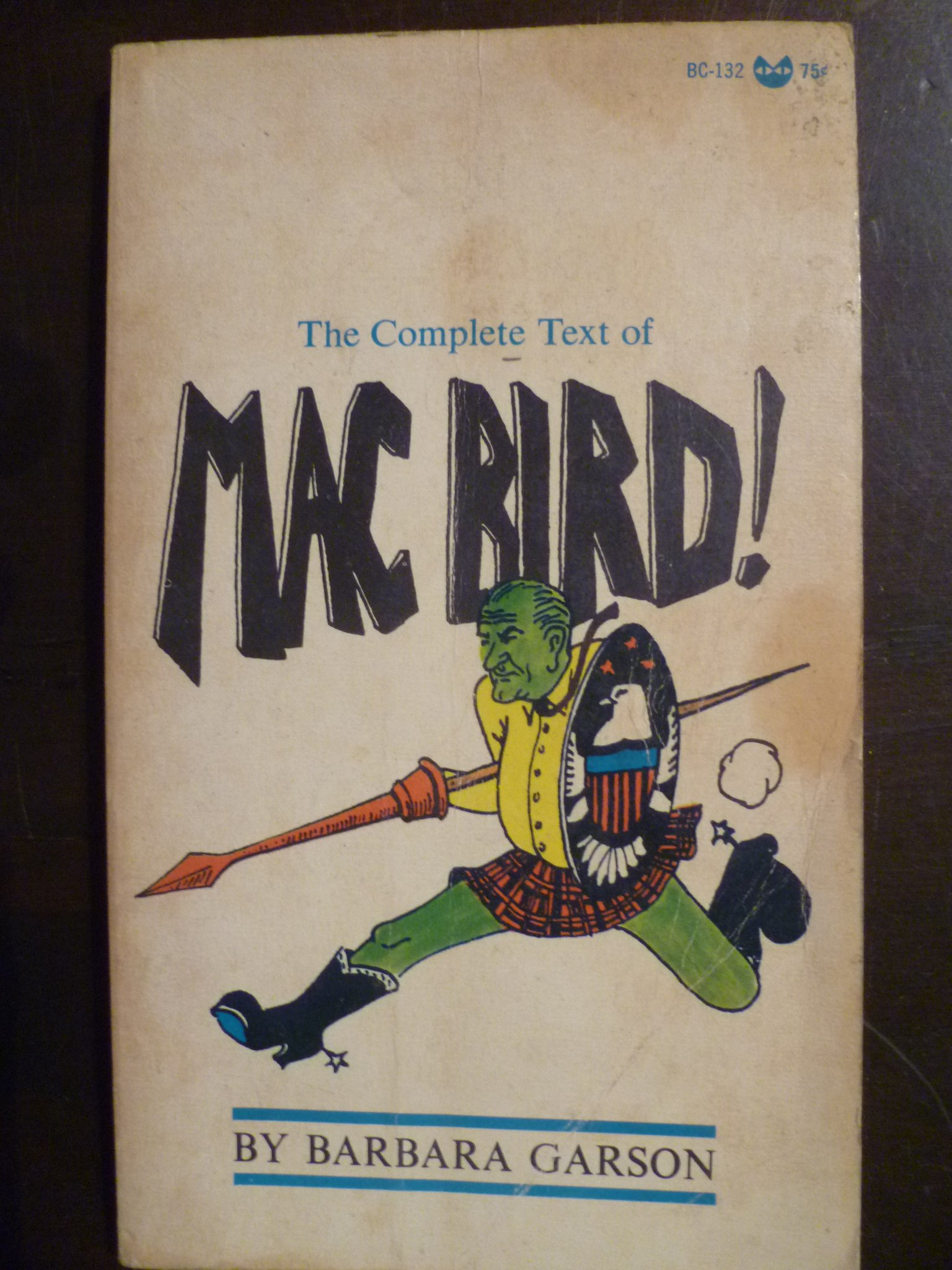

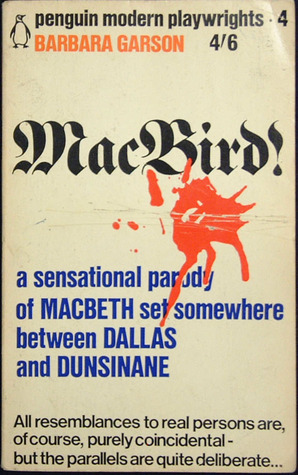

And in the middle of all that came MacBird.

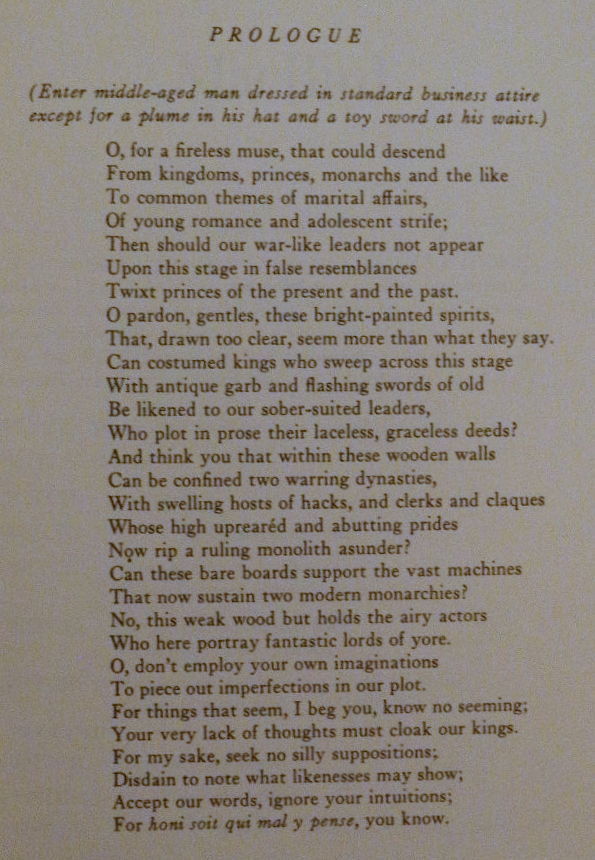

Garson had tried to get the leaders of the VDC teach-in to let her have a skit performed. It didn’t happen – the theater group fell through and she had differences with Jerry Rubin who was one of the leaders of the VDC. She kept at it. “I discovered that I loved writing in iambic pentameter. Things just fit in. It is one of the greatest sources of pride in my life.”

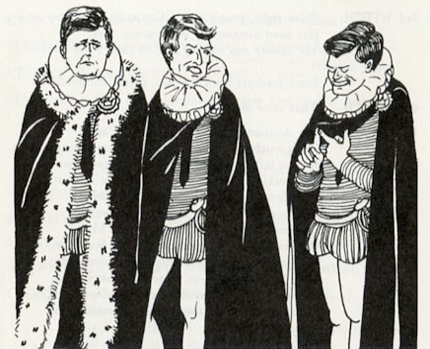

The conceit is Shakespeare’s MacBeth recast with President Kennedy and President Johnson. She explains the original idea – “During the Free Speech Movement I was at a big rally. I made a slip of the tongue and referred to Lady Bird Johnson as Lady MacBird. Then the whole thing just clicked.”

The play is often seen as an indictment of Johnson and his possible role in the Kennedy assassination. Garson disputes this – “This play wasn’t anti-LBJ, and it didn’t seriously suggest that he had President Kennedy killed. What I saw was that the Kennedy family and Johnson had the same politics, yet the Kennedy men were considered so beautiful and Johnson was considered so ugly. Why was that? My ultimate message was – let us on the Left not jump on the Democratic party bandwagon so quickly and easily.”

The play is often seen as an indictment of Johnson and his possible role in the Kennedy assassination. Garson disputes this – “This play wasn’t anti-LBJ, and it didn’t seriously suggest that he had President Kennedy killed. What I saw was that the Kennedy family and Johnson had the same politics, yet the Kennedy men were considered so beautiful and Johnson was considered so ugly. Why was that? My ultimate message was – let us on the Left not jump on the Democratic party bandwagon so quickly and easily.”

“The first edition of 10,000 or 15,000 copies was typed on an IBM Selectric typewriter and offset printed by the FSM press. It really caught on after a while.

“The first edition of 10,000 or 15,000 copies was typed on an IBM Selectric typewriter and offset printed by the FSM press. It really caught on after a while.

“As it evolved from a skit to a play, I sold hundreds of thousands of copies, more than half a million.The wonderful illustrations are by my fellow Berkeley FSMer Lisa Lyons.”

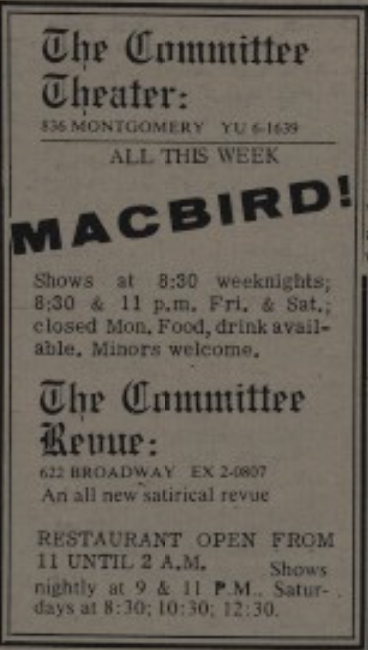

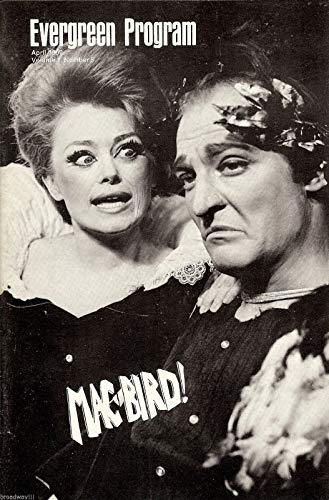

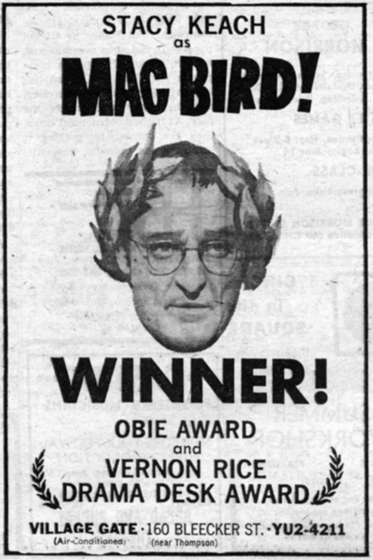

It was never seriously performed in Berkeley, going straight to New York, where it opened at the Village Gate in 1967 with a cast including Stacey Keach, William Devane, Clevon Little, and Rue McClanahan.

There were plans to take MacBird on the road but the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy in 1968 put the brakes on that so it was not produced in many cities.

The critics were boffo.

Dwight MacDonald in the New York Review of Books said that it was “the funniest, toughest-minded, most ingenious political satire I’ve read in years.”

Robert Brustein wrote in The New Republic that “it will probably go down as one of the brutally provocative works in the American theater as well as one of the most grimly amusing.” He called Garson “an extraordinarily gifted parodist.”

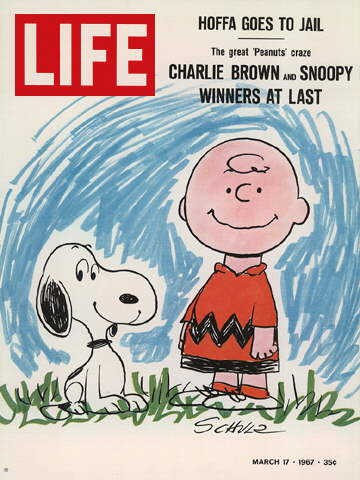

Life magazine in its March 17, 1967 issue told America that “a young housewife, Barbara Garson” had written a “little skit that grew too big for its britches” and had become “one of the oddest wonders of the American stage.” A young housewife????????

So there she was, not yet 30 years old, a superstar.

Garson left Berkeley right after the 1969 Memorial Day March in support of People’s Park. “With the National Guard occupying Berkeley, it felt like the funeral of People’s Park.”

She moved Tacoma, Washington, to work in anti-war GI coffee house. She was tired of the cult of personality and the MacBird fame, which didn’t carry over to Washington State.

All four branches of the Armed Services operated in Washington State during the Vietnam War,. The Fort Lewis Army Base in Tacoma served as an embarkation and training center for troops deploying to and returning from Southeast Asia.

The Northwest had a long history of progressive social movements and so it was not surprising that it became a strong center for GI antiwar activity and that its GI coffee houses and underground newspapers became nationally known.

The regional GI movement was strongest at Fort Lewis. There was an off-base coffee house for GI’s and there were underground newspapers – Counterpoint and Fed Up.

The coffee house was named The Shelter Half.

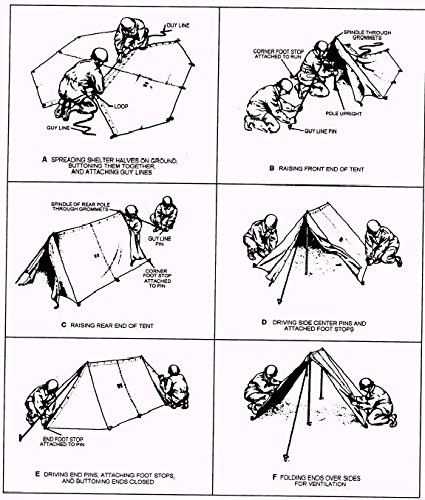

A shelter half is a 3-by-5-foot piece of sticky canvas, issued to every soldier in the field: one shelter half is useless, but when two are joined together, it creates a comfortable two-person tent. Good metaphor!

The Shelter Half operated at 1902 Tacoma Avenue from 1968 to 1974. It served as an anti-war headquarters, publishing underground anti-war newspapers, organizing boycotts, connecting civilian activists with local GIs, and leading peace marches.

It was good work for a single mother with a young daughter. At the coffee house there were people to talk to and play with her as Garson worked. It was very satisfying political work and the sectarianism that had descended on Berkeley was not present. And – people didn’t know she was FAMOUS, that she was a FAMOUS PLAYWRIGHT. In a 1906 letter to H. G. Wells, the philosopher William James wrote that: “The exclusive worship of the bitch-goddess Success is our national disease.” Aldous Huxley helped focus this a bit in saying: “The point of William James’s statement is that reaching Success demands strange sacrifices from those who worship her.” Away from Berkeley, Barbara Garson could just be Barbara Garson.

Garson moved back home to New York in 1974 and has stayed there since. She wrote other plays and nonfiction – a series of books describing American working lives at historical turning points. These books, including All the Livelong Day and the Electronic Sweatshop, document the historical trend we have come to call “inequality.” She has remained a dedicated social activist working for peace and freedom and justice and equality.

Garson has been back to Berkeley a few times. “At one point, it seemed like Telegraph Avenue was a teenage slum now. Free speech now had been appropriated by vendors and religion and more recently an occasional right winger using Berkeley as a prop.” She still has many friends in Berkeley and enjoyed her recent visit for the FSM reunion.

So – a long story! Barbara Garson has led an extraordinary life – politics, creativity, humor, and a love of iambic pentameter. She lived in Berkeley at an extraordinary time and was fully engaged in a series of history-changing movements. We were lucky to have had her with us.

I showed the draft post to my friend. He was engrossed reading everything that he could find on Detroit’s Prophet Jones, the Messiah in Mink, who preached “An open mind, a clean heart, and one dollar, please.”

My friend pushed away the stack of Prophet Jones material and read this post. “Damn!” he said. “Hunter Thompson and his ‘Norman Luboff should have his nuts ripped off with a plastic fork’ – damn!”

I sensed a story coming. I wasn’t wrong.

“My dad was the world’s biggest Norman Luboff and Norman Luboff Choir fan.

“He wouldn’t miss The Railroad Hour on the radio when Luboff was the show’s choral director. ‘That Luboff knows his choral arrangements!’ he’d say.

“And then at Christmas –

“Nothing but Luboff.”

Who knew?

“And, by the way, nice job with James’s. I think you got it right.”

I told him that while I appreciated the little details that he had noticed, what about the big story? What about this story about Barbara Garson in Berkeley?”

Tom ~ This is a fascinating post. Congratulations on historically informing us.

Hillbird (Johnson I think that’s his last name) = Hilbert J. Coleman