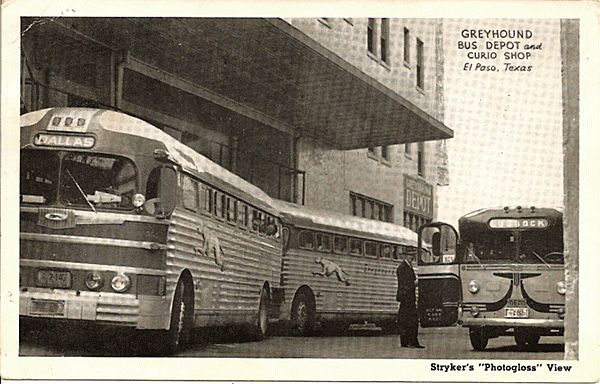

My friend Gabby grew up in Nekoosa, Wisconsin. In 1967, in the spring of his senior year in high school, he took the Greyhound to the Rio Grande Valley for a senior project with striking melon workers, a senior project that turned into 12 years of working for the United Farm Workers. Here is what he wrote about that bus trip:

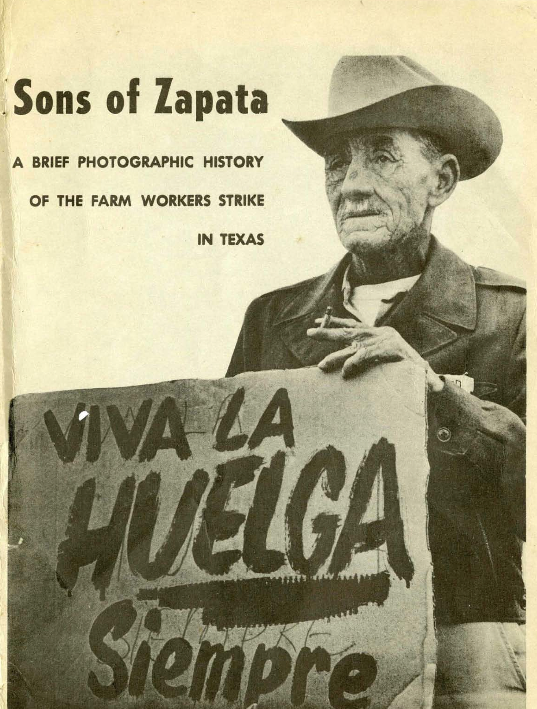

In the spring of 1967, with the help of a radical priest with connections to the paper unions in Wisconsin Rapids that steered him to the nascent grape boycott in Madison and Milwaukee, I convinced the authorities at my school (Assumption High School in Wisconsin Rapids, ten miles from my Nekoosa home) to give me independent study credit for going down to the Rio Grande Valley in Texas to investigate a strike by migrant Mexican melon workers.

I knew very little about the situation, and much of what I knew was suspect, derived as it was from a local rightwing whack-job television commentator who projected large and grainy black and white photographs of the farm worker march on Sacramento in 1966 and with a white marker showed Tri-cities viewers the “known and suspected Communists and Communist-sympathizers” in the crowd.

“To make a long and meaningless story short, I Greyhounded down to Rio Grande City, Texas, where the melon strike was taking place.

“I was just 18 and like so many boys at the time who were just 18 I experienced the almost-2000 miles on the bus mistaking myself for Jack Kerouac on his way to unknown places, jotting in my notebook, whispering Wolfe to myself – “I will go up and down the country and back and forth across the country. I will go out west where the states are square.”

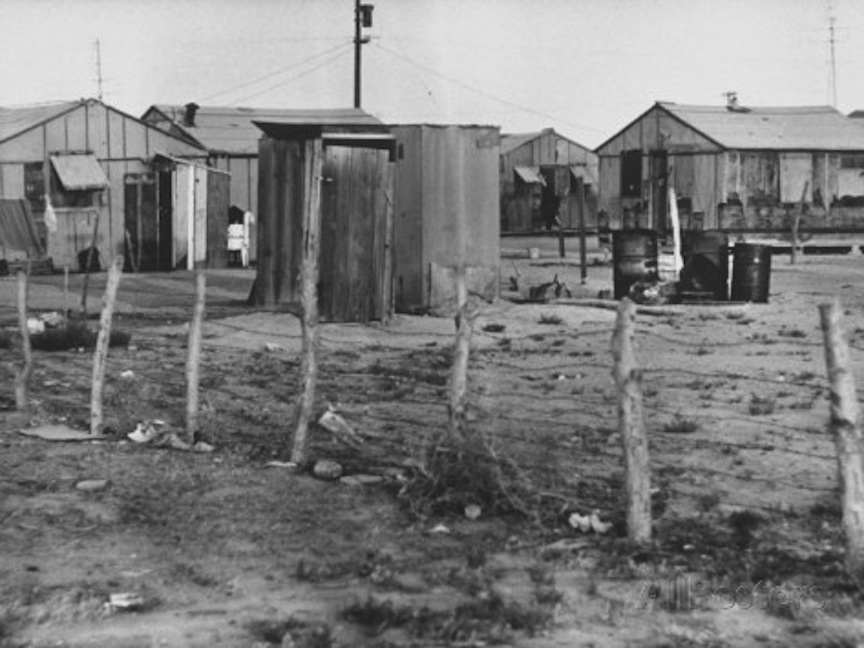

No worse for the wear after three days on the bus with washing limited to cold water splashed on my face at stop-overs on the way down, I found myself in Rio Grande City at lunchtime in early June. It was quite hot, in fact hotter than I thought it was anywhere, dusty, quiet, faded paint on Mexican grocery stores with music from radios inside spilling out, a few sad palm trees and lots of sad old cars, kids running around with sodas – desolation row and – I loved it.

No worse for the wear after three days on the bus with washing limited to cold water splashed on my face at stop-overs on the way down, I found myself in Rio Grande City at lunchtime in early June. It was quite hot, in fact hotter than I thought it was anywhere, dusty, quiet, faded paint on Mexican grocery stores with music from radios inside spilling out, a few sad palm trees and lots of sad old cars, kids running around with sodas – desolation row and – I loved it.

I was on the ankle express. I spotted a lunchspot, the Catfish Inn. Outside stood a policeman and me being a nice young man from Wisconsin I thought I’d ask directions.

His name, it turned out, was Captain Allee. He worked for, it turned out, the Texas Rangers. He was, it turned out, the single greatest enemy that the United Farm Workers ever had. He was nice enough to me, amused I think at my naitvite or, perhaps, impressed with my searsucker sports jacket.

He pointed out a handsome-in-a-David-Nivens-way man driving by in an old slant-six Valiant, pulling into a parking space in front of an office a block east of where we were. He said, “That would be who you want to talk to.” I did.

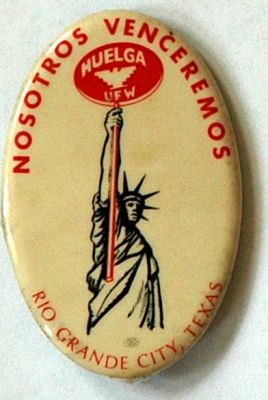

He gave me a Union newspaper to read up on, gave me a button, and advised me to take off my necktie and lose the searsucker jacket and did I have any shoes besides the penny loafers and in a few minutes he would take me to go meet Lance the lawyer who I had arranged to meet.”

* * * * * * * * *

And so Gabby came to the United Farm Workers. In this account, he used the name “Lance” when he was referring to Jerry Cohen, the general counsel of the Union. I am not sure why he did.

I asked my friend about these photos and Gabby’s story. He showed me something that he had been looking at.

“Dude, Starr County Texas was pre-capitalist. It was stone feudal. No joke bro, it was a feudal set-up and Allee was the enforcer for the lords.” What does he think of the story, of the photos? Of Gabby’s entrance?