I continue here my examination of the fast-disappearining industrial Berkeley, using William Blake’s glorious phrase “dark satanic mills.” Bruce Springsteen isn’t in the Blake league, but when he writes about his father’s job at a rug mill he is spot-on:

I continue here my examination of the fast-disappearining industrial Berkeley, using William Blake’s glorious phrase “dark satanic mills.” Bruce Springsteen isn’t in the Blake league, but when he writes about his father’s job at a rug mill he is spot-on:

Through the mansions of fear, through the mansions of pain,

I see my daddy walking through them factory gates in the rain

We had our factories, and with them solid working class jobs that gave us cultural and economic diversity. I don’t romanticize or glorify the difficult working conditions in these foundries or the environmental havoc they wrought. I accept the bad but celebrate the positive – the good, mostly union jobs that gave us some degree of economic balance. I also appreciate the industrial architecture in West Berkeley.

For today’s post, we finished our tour of industrial Berkeley north of University, focusing on Second Street north of Gilman and south of Cedar. The vast wilderness to the south of University still awaits us.

Recycling and trash transfer have a a gritty vibe.

Especially these last two. Lots of trash, no?

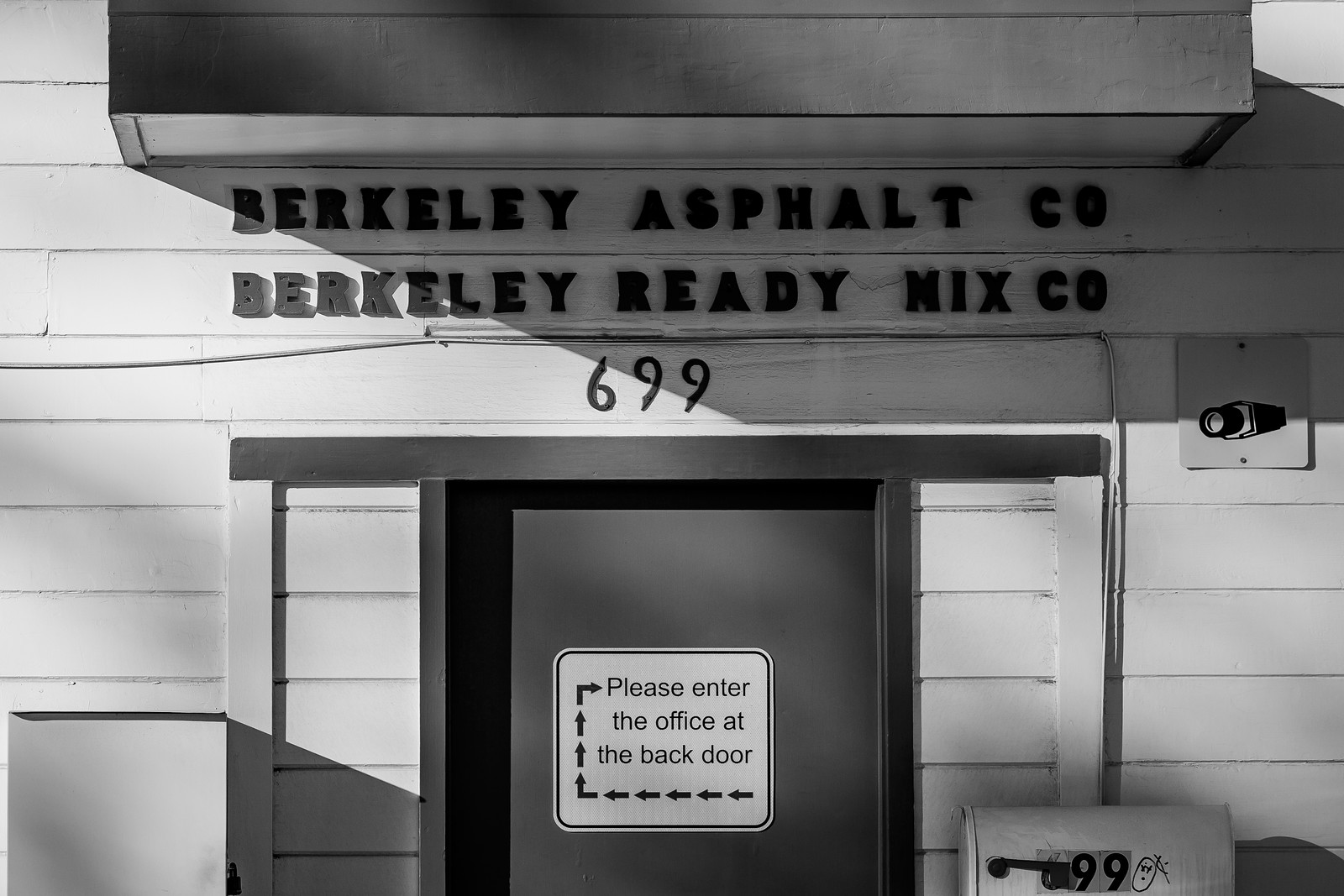

Truitt and White was started in 1946 by wartime Navy buddies George Truitt and Robert White, who were both assigned to the material procurement department. This signage is won-der-ful. Classic.

We know that I’m all about names. Robotic Welding is a GREAT name.

The next set of photos shows what you can see on Sixth Street at Picante looking west.

I have one final photo. It’s something of a bring-down.

Nothing charming or pretty or romantic about this. But – it gives me the chance to slip in some music – “The Dark End of the Street” with possible versions by James Carr and Ry Cooder. Not to mention the versions by Percy Sledge, Aretha, Porter and Dolly, the Commitments, the Flying Burrito Brothers, etc. A pow-er-ful song.

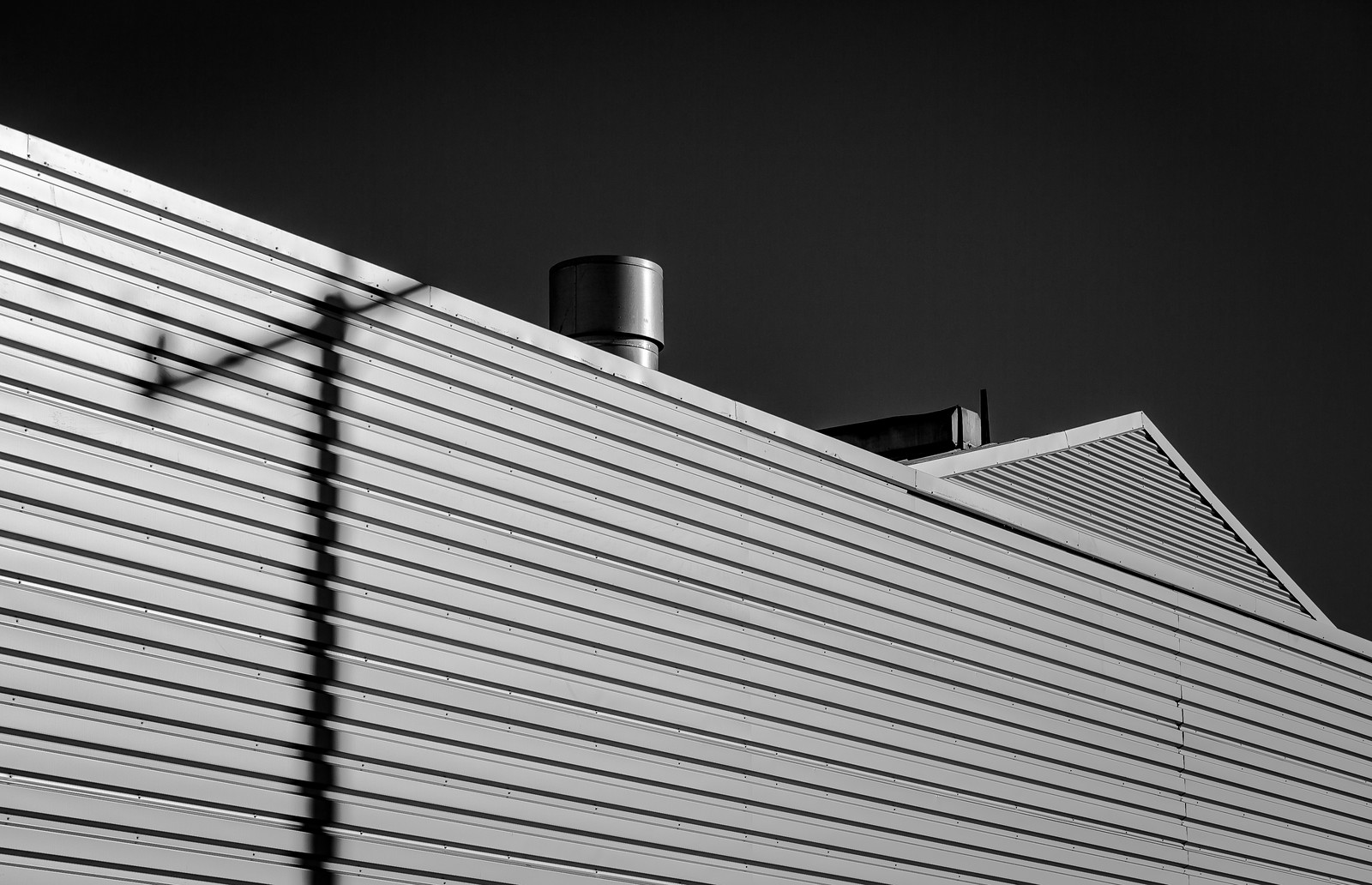

The point of these stunning photos by John Storey is this – look around you. Ignore nothing. Take nothing for granted. Assume nothing. See Berkeley with an unconditioned eye, an eye that is open, innocent, and wild. See with the eye of a beginner—uninformed and constantly searching.

I wondered if the black and white photos give the satanic mills an edge. I took two of my Most Ugly New Architecture sites and show them as black and white.

Bay Street – a self-described “Urban village” developed on a former industrial brownfield site.

Bay Street – a self-described “Urban village” developed on a former industrial brownfield site.

And Parker Street Apartments, self-described as “Daring. Artistic. Berkeley. Feel alive. Be delighted. Choose your own adventure at Parker Apartments. Ahead of the trends and out of the box, our downtown Berkeley apartments feature bold, modern design.”

Is that a cheap shot, using their own ad copy against them. I think not. And I think that I have answered my own question – black and white doesn’t make them look cool

Even the busted-down, slutted-out used car lot across from the Parker Apartments looks cool in black and white.

Industrial Berkeley reads cool in the photos because it is cool.

I took a print-out of this post in draft form to my friend. We sat at his Kai Kristiansen rosewood dining table. For a while he crushed super hard on Kirstiansen’s design.

He had a large manilla folder in front of him, llabeled “VASE.

Like many of us,my friend had seen the blurb in Berkeleyside that among the Spenger’s memorabilia to be auctioned at Clar’s Auctions is a rare, Meiji-era vase thought to be missing since it was last seen at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Meiji-era, you ask?

In 1868 the Tokugawa shôgun who ruled Japan in the feudal period lost his power and the emperor was restored to the supreme position. The emperor took the name Meiji (“enlightened rule”) as his reign name; this event was known as the Meiji Restoration. The Meiji period ended, with the death of the emperor in 1912.

From this article, we learn more about the vase:

A Kilburn stereoscope card titled “Japanese Vases, Value $50,000 Columbian Exposition” showing the three-piece cloisonné garniture in the Palace of Fine Arts in 1893. [Image from the Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California at Riverside.

“Their figures of birds and animals are symbolic of the seasons and the virtues” writes one World’s Fair historian, but the imagery also had important political messages. The dragon image on this second vase represents China.

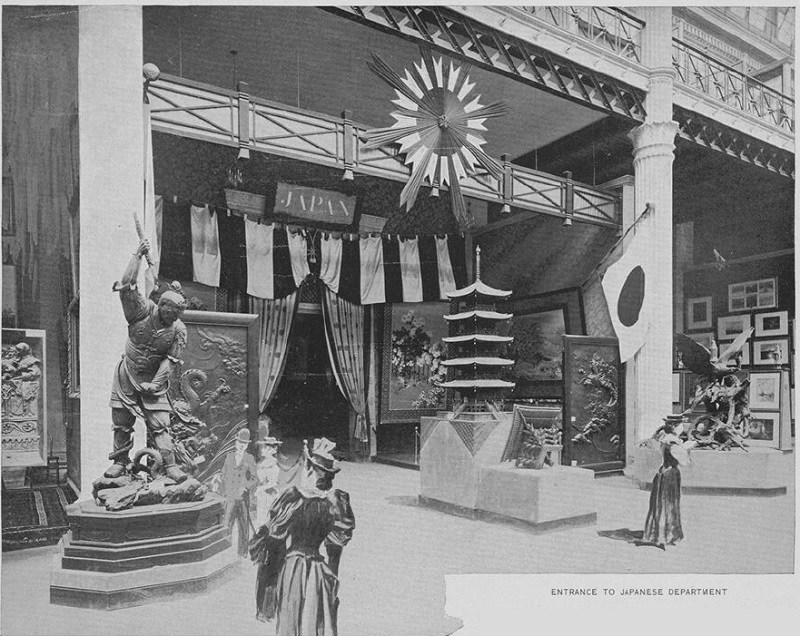

Entrance to Japanese Department of the Palace of Fine Arts. [Image from Hubert Howe Bancroft’s The Book of the Fair (The Bancroft Company, 1893).]

The triptych was exhibited in the Art Palace, in the west end of the East Court of the ground floor, near the central rotunda. (Revised Catalogue, 392) The catalog of the Fine Arts department the Exposition offered this description of the display:

Two vases and an incense burner, in Cloisonné.These three pieces are the largest examples of Cloisonné enamel ever made. The vases are eight feet eight inches high. Work upon them was begun in 1890 and finished in January, 1893. They were designed especially for exhibition at the World’s Columbian Exposition, and upon their completion were viewed by the Empress of Japan.

The designs on the vases were the idea of Mr. Shin Shiwoda, Special Counsellor for Arts of the Japanese Commission to the World’s Columbian Exposition. Their manufacture was undertaken by Mr. Shirozayemon Suzuki, of Yokohama, with the co-operation of Mr. Seizayemon Tsunekawa, at Nagoya. The original design was painted by Mr. Kanpo Araki, of Tokyo, and the black ink sketch on the copper was made by Kiosai Oda, of Nagoya. The men directly in charge of making the vases were Gisaburo Tsukamoto and Kihio ye Hayashi, of Toshima. The design for the wood carving was made by Setsuko Nishiyama, of Nagoya, and the carving was done by Kinzaburo Yeguchi, of Nagoya. The bronze American eagle was made by Yukimune Sugiura, of Tökyö. The general design represents the seasons of the year: the group of chickens typifying spring; the dragon, summer, and the two eagles, autumn; while on the reverse, with two red eagles, a winter scene is portrayed. The same design also symbolizes three virtueswisdom, honesty and strength, symbolized respectively, by the dragon, chickens and eagles.

Another idea conveyed by the front design is, that the dragon typifies China; the two eagles, Russia; the group of chickens, the Corean Islands, and the rising sun, the Empire of Japan; while the bronze eagle on the cover of the censer is the American eagle.

The silver stars inlaid on the horizontal red and white stripes on the top of the vases and censer are emblematic of the American stars and stripes, while the chrysanthemums and other Imperial floral emblems strewn on the stripes symbolize the close friendship between Japan and the United States. The handles of the vases are shaped after chrysanthemum leaves—the chrysanthemum being the imperial crest of Japan.

The blossoming cherry tree on the censer is symbolic also of spring. The full moon with the flight of birds, on one of the vases, symbolize summer and autumn. The lower portion of each vase shows bouquets of grasses of flowers native to Japan.

The pedestals on which the vases rest are made from keyaki, a hardwood tree grown in Japan, the wood of which is prized for its fine grain and durability. The pieces from which the pedestals are formed are two hundred years old, having been taken from a temple recently destroyed by an earthquake. The panels in the pedestals are carved from this wood and show seventy different specimens of flowers.

This is where my friend stepped in. How did said lovely vase end up in Spenger’s? If anybody noticed it among all the mounted fish and ship models and maritime memorabilia, I’m guessing they assumed it was a cheap knock-off from Chinatown.

My friend had immersed himself – and I do mean immersed – himself in solving the mystery. He has well over a hundred hours invested in his research – newspaper morgues, diaries, library archives, and old photographs. He is near certain that he has cracked the case. I will let him tell the story when and if he wants to.

I congratulated him on his work and asked about the photos I was showing him.

“First thing,” he said, “don’t think that I don’t catch that ‘Second Verse’ is from that scourge of a Herman’s Hermits song ‘Henry the Eighth.’ But here’s what you don’t now about it.”

“It was a music hall song by Fred Murray and R. P. Weston, written in 1910. It was a signature song of Harry Champion, big Cockney accent, Henery or Enery. Colin MacInnes wrote in The New York Times that Champion ‘used to fire off [the chorus] at tremendous speed with almost desperate gusto, his face bathed in sweat and his arms and legs flying in all directions.’ Alvin and the Chipmunks covered the song, and I think I like it better than Herman’s Hermits. Their version knocked ‘Satisfaction’ off Billboard Number One. What was the matter with us?????/”

Wow. Digression after digression.

What about the dark satanic mills part of the post, my friend?

Love your posts, all the research, the photos! Thanks!!!!