The pandemic and the resulting social isolation have put me through some changes, most relevant of which for these purposes is that I stepped away from Quirky Berkeley. I don’t know for how long or under what conditions, but today I return with a story and photos of the loving, quirky art of Avram Gur Arye.

He lives at Redwood Gardens, a 169-unit HUD-subsidized, senior-designated property in Berkeley on Derby, in a structure built for the California School for the Deaf and Blind in 1922.

Art – his and the art of others – informs every wall. His 82 years on this earth prepared him for this room and this art.

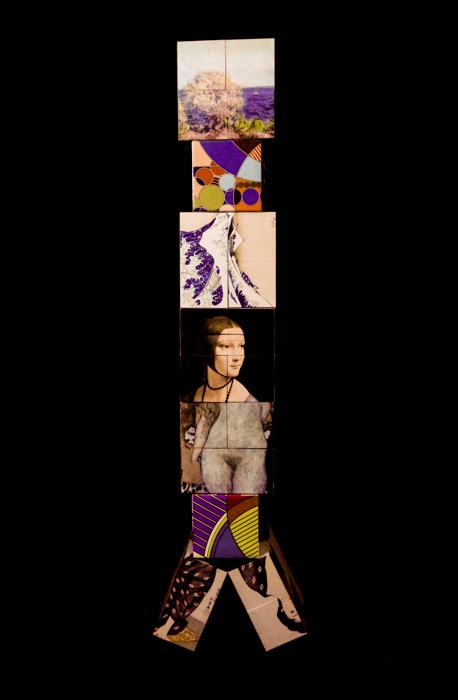

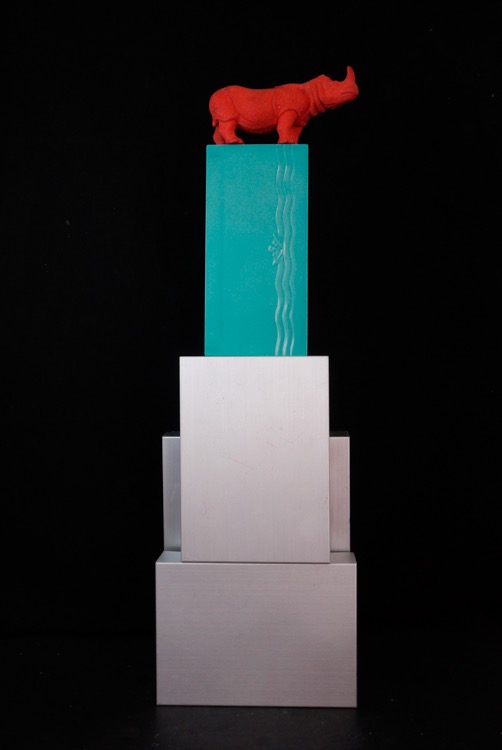

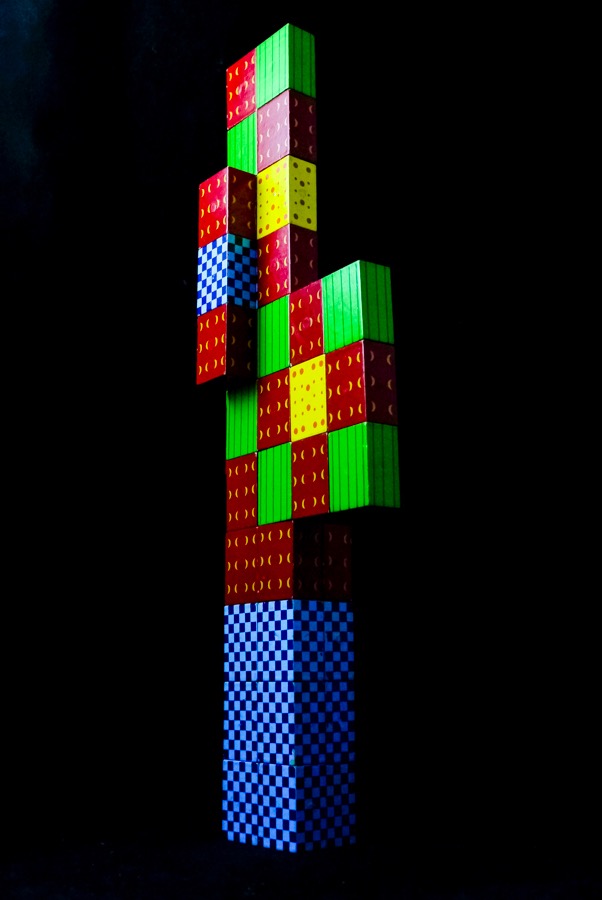

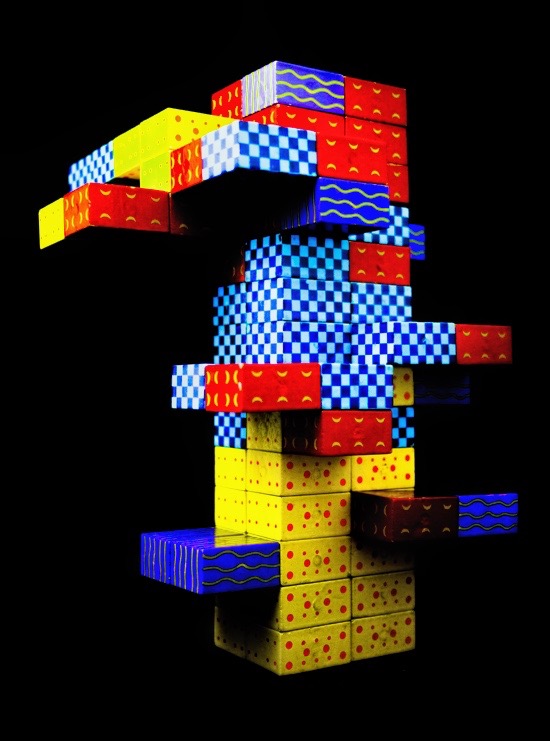

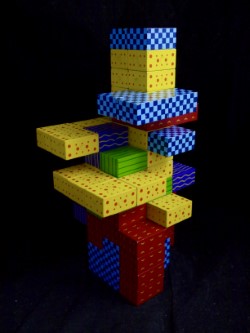

He makes his assemblage/diorama/art in his studio apartment. With the necessity of a small space as the mother of invention, Arye photographs the assemblages that he makes; those photographs, along with the stories that he composes, form the end-product of his art. I kind of wish I’d taken this approach before I built 20 or 25 shadow boxes.

When he is done with a story, he packs up the pieces and starts on a fresh project.

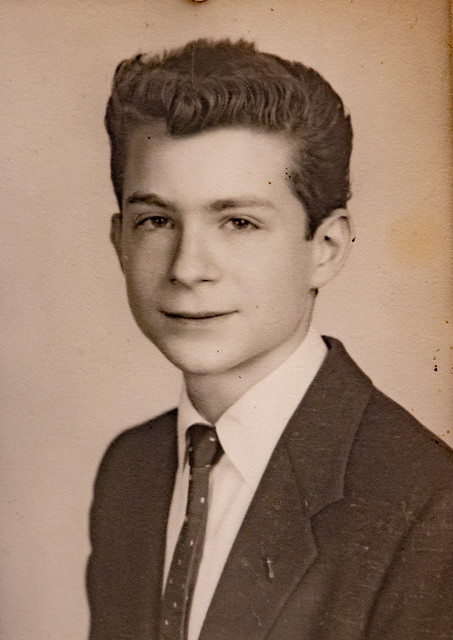

Arye grew up in the Bronx, living with his mother and his Yiddish-speaking, Lithuanian-born grandmother. His father, who worked for Bell Labs, disappeared in 1941, when Ayre was almost two.

From age two until age five, Ayre lived in New Jersey with a Quaker family who ran a private boarding school. His mother and grandmother worked and couldn’t juggle their jobs with a young Avram.

When the war ended, Avram came home to the playground called the Bronx – movies on Jerome Avenue, the local bagel shop, two-sewer baseball, cards and coins and marbles, and salugi. New York word maven Barry Popik describes salugi as follows: “An unorganized game among children in which an article is snatched away from a victim and tossed back and forth among the tormentors; also used as a call in the game.”

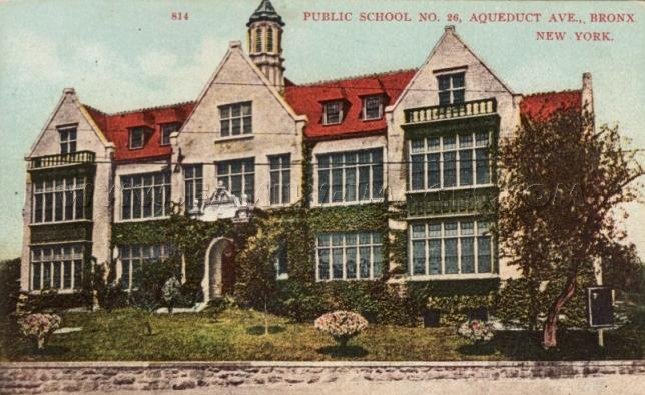

Avram attended PS 26 at Andrews Avenue and West Burnside Avenue in the Bronx. Teachers lived in the neighborhood and knew the students and their families. Young Avram often found himself in the principal’s office explaining why he had done what he had done or why he had left undone that which he had left undone.

After PS 26 came the Bronx High School of Science. The curriculum was science-driven.

For the first time in his life, Avram found a class – evolution – to be challenging and interesting.

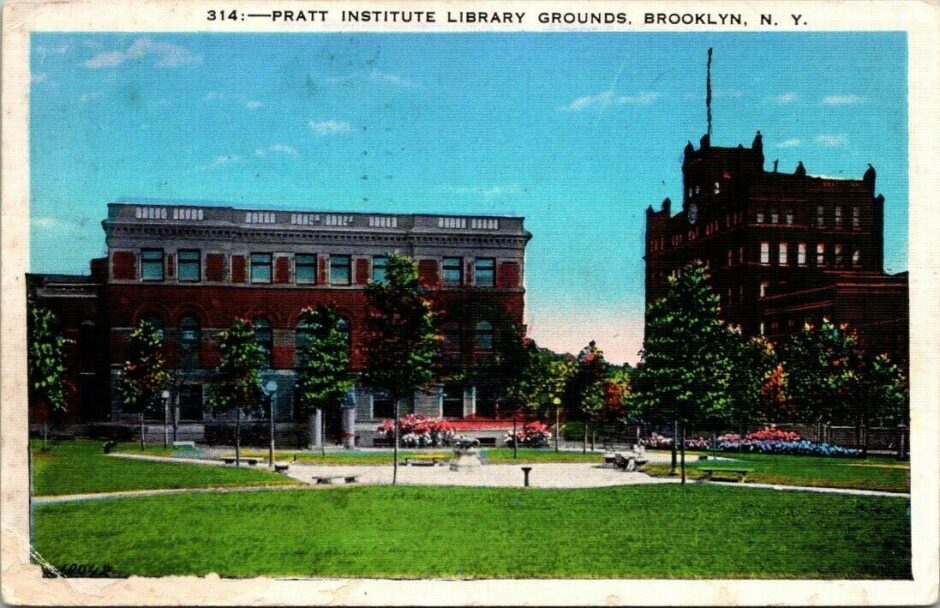

He graduated from high school in 1957 and matriculated at the Pratt Institute, a private university in Brooklyn. Its effect on him? “Then my life began.”

His mother worked at Rockefeller Center – he loved it. Avram worked as a messenger boy at the Rockefeller Center, walking Manhattan delivering messages and inhaling the city. He loved the work of Mies van der Rohe, especially the Seagram Building. He loved Le Corbusier, especially the Lever House on Park Avenue, the design of which incorporates ideas proposed by Le Corbusier in the 1920s.

At Pratt, he embarked on a five-year program studying architecture, a passion that he discovered on a trip to Mexico with his mother when he was 16. The blend of colonial with Aztec and Mayan and bright colors made the hair stand up on the back of his neck. He found the same inspiration in the Calle Ocho neighborhood in Little Havana, Miami.

He married during his final year at Pratt. He and his young wife moved to San Francisco after graduation.. Like many easterners move to California, he envisioned a surfer on every corner.

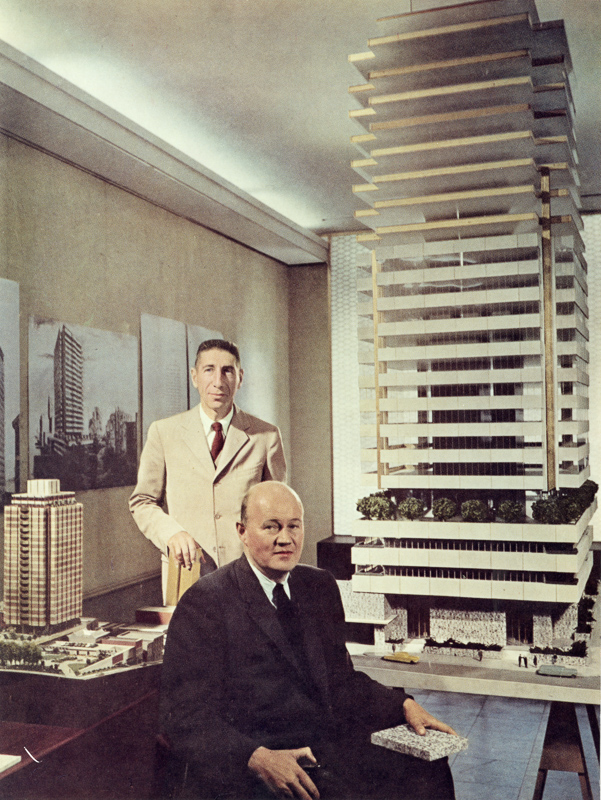

He took a job with Anshen and Allen. Shown in this photo is the model of the shipping line office that they designed and which was Avram’s first job in their office – designing the ticket office.

They were an architectural firm that made its reputation in the 1950s building over 3,000 houses for the developer Joseph Eichler and his model of affordable, mid-century modern-style housing tracts.

Avram left Anschen and Allen after three years, wanting more supervision in a smaller firm working on smaller projects. He divorced and moved from Noe Valley to downtown. He had a small firm that did small jobs. He learned by doing, a quintessential autodidact.

On the side, he made art with Prismacolor Premier Colored Pencils.

And then the onset of a bipolar disorder took him out of architecture for ten years. Destroyed by madness, starving, hysterical, naked, he was determined to control the disorder without medication, especially without lithium, which he found destructive of his creativity. He lived off savings with stints in retail jobs. He systematically fought cycles of uncontrolled automatic negative thoughts.

During his ten years in the figurative wilderness, he painted – highly detailed, larger scale paintings. He worked with photography, first with slides and then digitally.

He went to work as an architect for an old boss, but it didn’t work out. Living in Albany, he heard about Redwood Gardens, applied for an apartment, and eventually got in. It is subsidized housing, which helped make up for the savings that he had spent for living expenses as he struggled with his bipolar disorder.

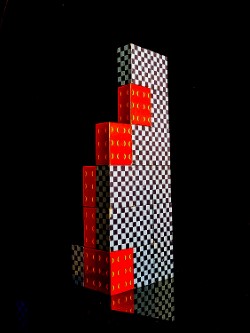

He found colorful magnetic blocks which served as the structural basis for many of his scenes. He has found a new set of blocks that he hopes to buy next month.

Photo: Avram Gur Arye.

For the assemblage figures (he calls them “toys”), he shops online and at toy stores – Sweet Dreams, Mr. Mopps, Five Little Monkeys, and Games of Berkeley – as well as Tail of the Yak and the now-closed Boss Robot Hobbies on College, and Barnes and Nobel and Urban Ore and the East Bay Depot for Creative Reuse. He lives on a fixed income, so every cent spent on toys is a cent not spent on food – on the whole, a fair trade.

He begins with a concept, such as a convocation at People’s Park. He experiments with placement of the toys and camera angles and lighting. He tinkers and tinkers more, moving the pieces, finding different angles.

Eventually, he senses from the toys an over-arching story, which he writes. He self-publishes books of photographs and their guiding story.

He works in a small room with a limited number of toys, but with an imagination and creative vision that are seemingly without limits.

The Black Madonna shown in this photo features prominently in Avram’s more recent work, much as the naked Eve stands out in many of the photos in this post. Sitting on the Madonna’s lap is Black Sarah, Sarah-la-Kali, an “Icon of Love and Welcome.”

The surge of creativity that passes through Avram is an inspiration. He walks to the Safeway on College every morning. He often makes his way north to Peet’s at Walnut and Vine. He knows people. He makes photographs all day, experimenting, getting better. He is drawn to crowds, to play, to conversation. He is a creative polymath.

And he works on his books, photographs that tell stories, stories about the photographs.

The path to here hasn’t been easy, and it isn’t always easy even now. He is driven by art, by inspiration, by creating.

Avram is a form of the name “Abram, ” the founding patriarch of the Israelites, Ishmaelites, Midianites and Edomite people. It means “exalted father.” I don’t want to read too much into things, and I’ve never used the adjective “exalted.” The word takes me to my nine years starting school each day with the Episcopal service of morning prayer and a minimum of two hymns – “In loud, exalted strains / the King of Glory praise….”

It’s a perfectly good word. If I were going to use it, I don’t know why I would not exalt our friend Avram. I grew up using the term “paralipsis” to describe what I just did – drawing attention to something by saying that you will not mention it. Since those schoolboy days of Warriner’s English Grammar and Composition, I have learned the word “apophasis,” a passive-aggressiove rhetorical device employed to bring up a subject by either denying it or denying that it should be brought up. Poor exalted Avram – sidetracked at the end of this post by a digression on grammar!

For many more of his photos, check out his Facebook page. For his self-published books, go browse at BLURB –

I showed the draft of this post to my friend, who has sadly descended into the hell of watching sovereign citizen YouTube videos. He used to have a gentleman’s grace, a scholar’s wit, and a soldier’s strength. He used to be the jewel of Berkeley, I hoped that seeing Avram’s work might snap him out of his universe of sovereign citizens. He looked up as I handed him the draft. “Did you know that in surveys conducted in 2014 and 2015, representatives of U.S. law enforcement ranked the risk of terrorism from the sovereign-citizen movement as greater than the risk from any other group, including Islamic extremists, militias, racists, and neo-Nazis?”

No, I did not know this. I also don’t know the long-term effect that showing him photos of Avram’s work will have, but I know what his reaction was – spot on.