Three generations representing the creative and individualistic bent of Berkeley in different ways, true to their time and the inventive spirit of Berkeley, had homes on the 2400 block of Oregon Street, running between Telegraph Avenue and Regent Street. Obata and Kael and Scherr.

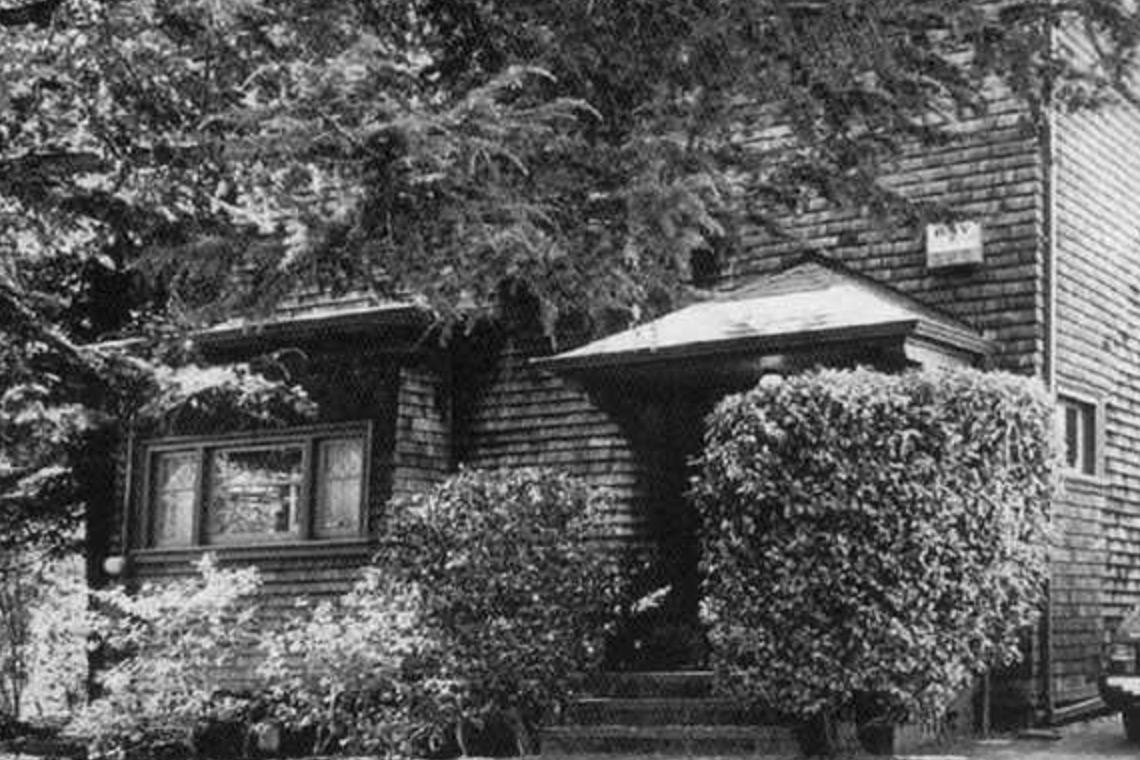

Chiura Obata lived at 2430 Oregon.

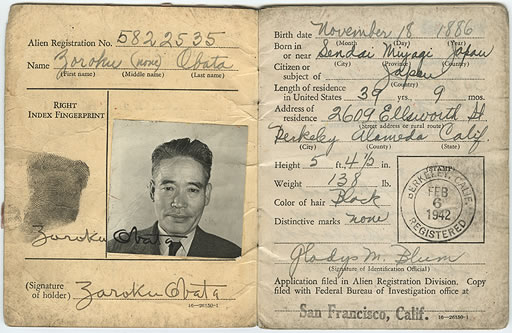

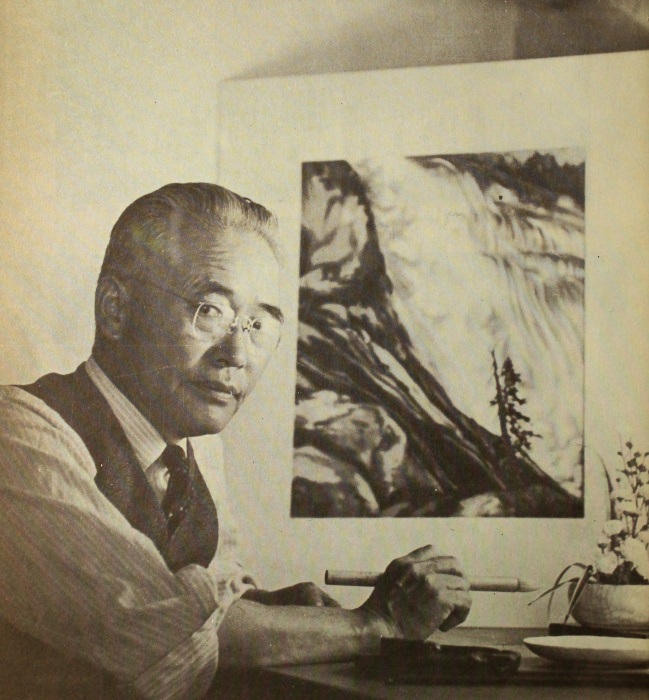

Obata was a Japanese-American artist and professor. He worked as an illustrator, a commercial decorator, and then as a professor at Cal from 1932 until 1954.

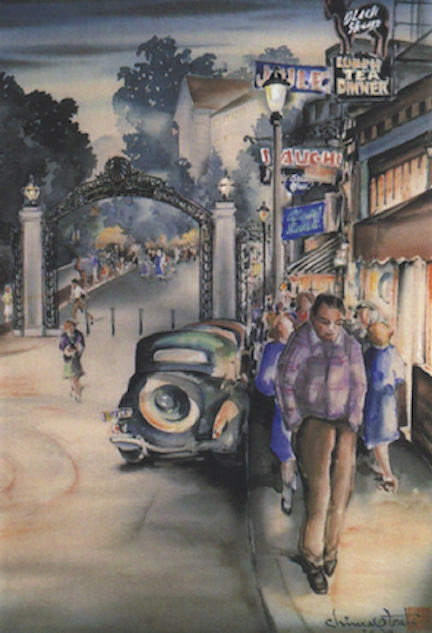

For the most part, he painted nature scenes. One exception is this painting – Sather Gate at Dusk (1939). It shows the “Lost Block” of Telegraph, from Bancroft north to Sather Gate, and the medieval-revival Black Sheep restaurant. This painting speaks to me.

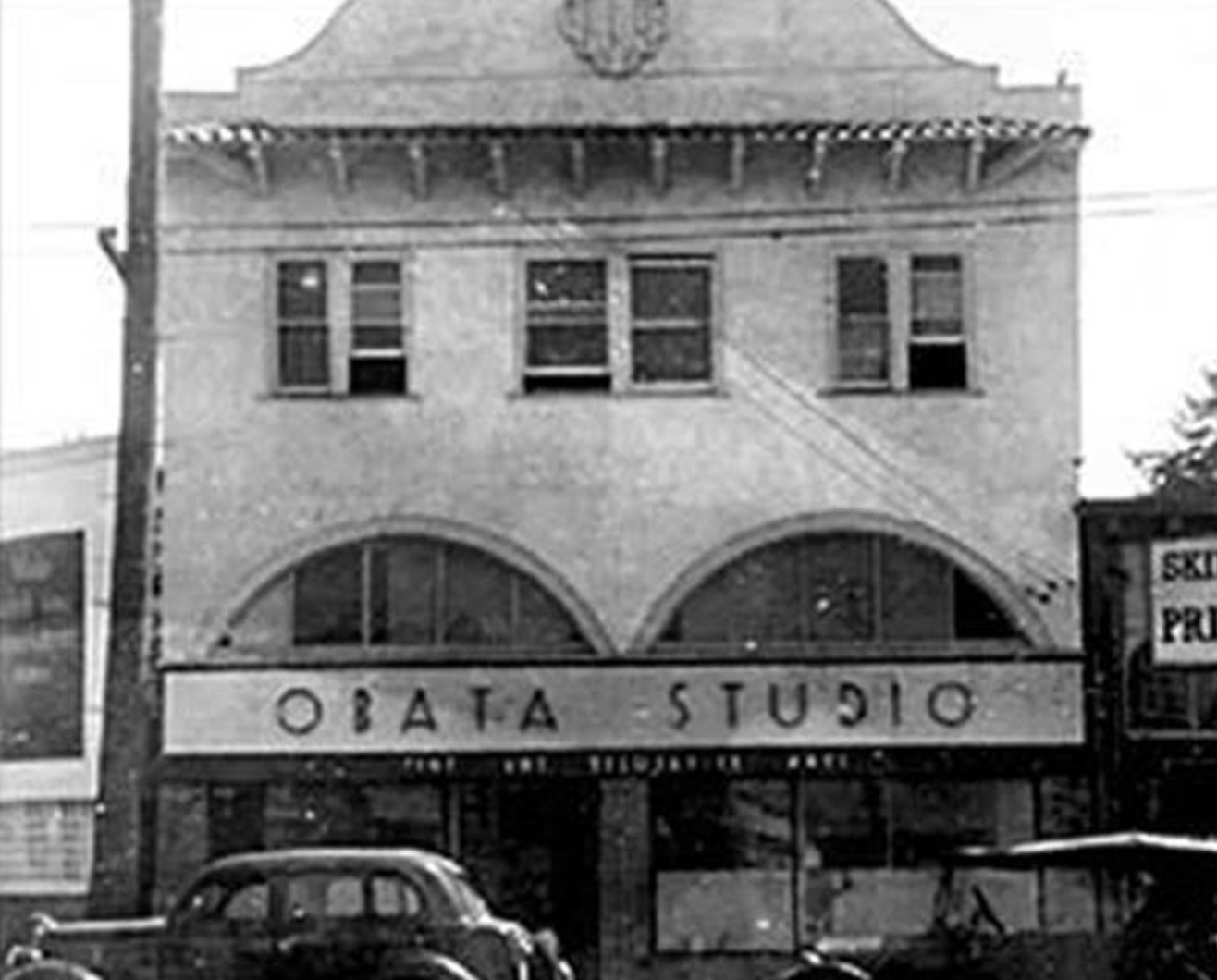

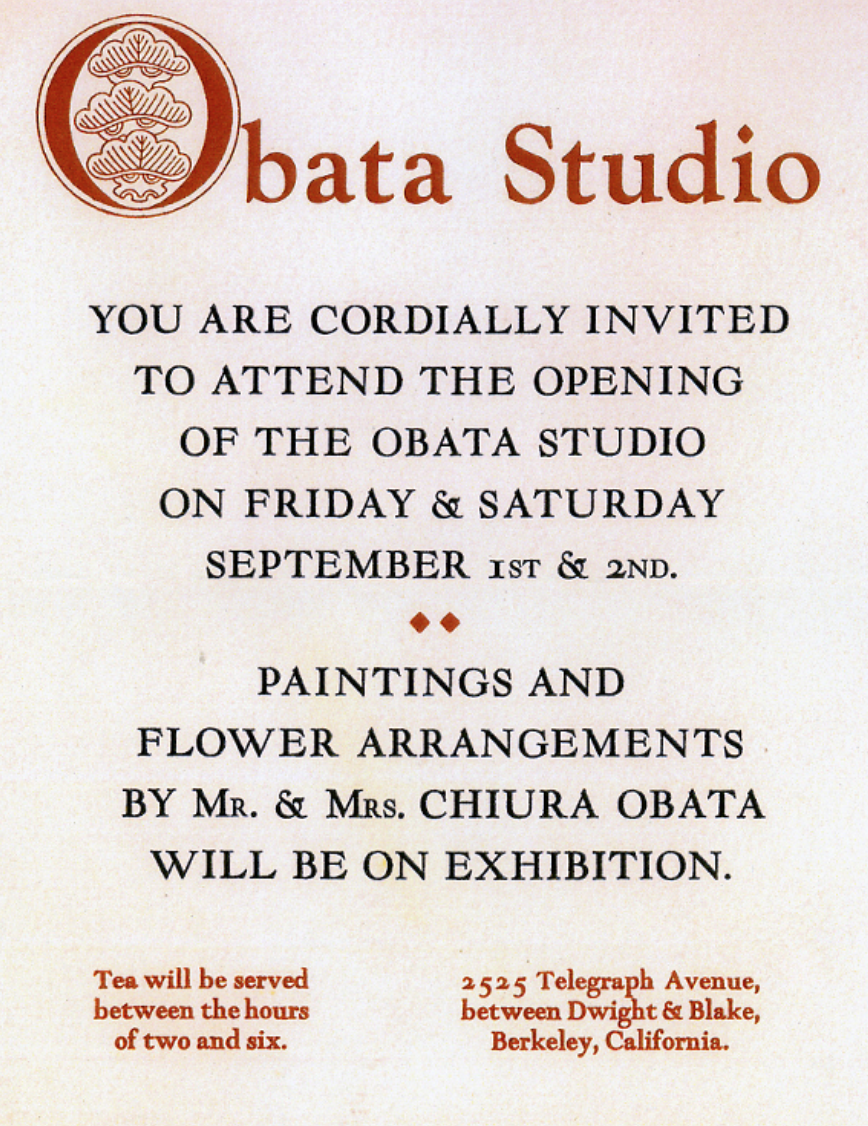

Obata and his wife had a audio / gallery / gift shop at 2525 Telegraph,

I don’t con’t have a complete list of occupants of the space after Obata, but it was the future home of Bluebeard Boots, Ma Revolution, and Half Price Books/The Blue Nile restaurant. It is without a business now.

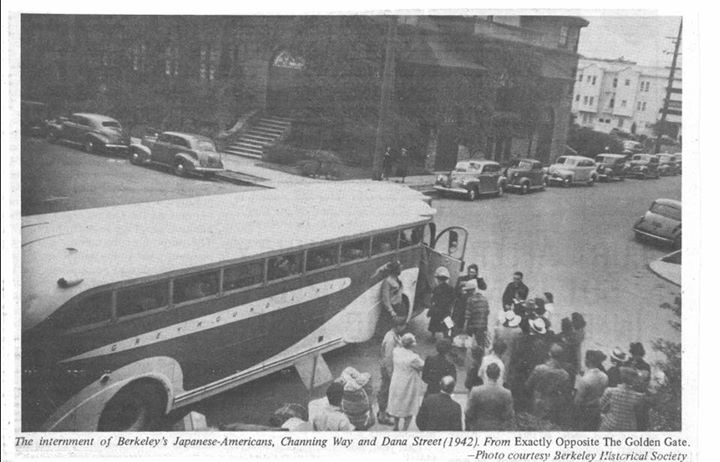

In 1942, Berkeley’s Japanese-descent citizens were relocated to internment camps.

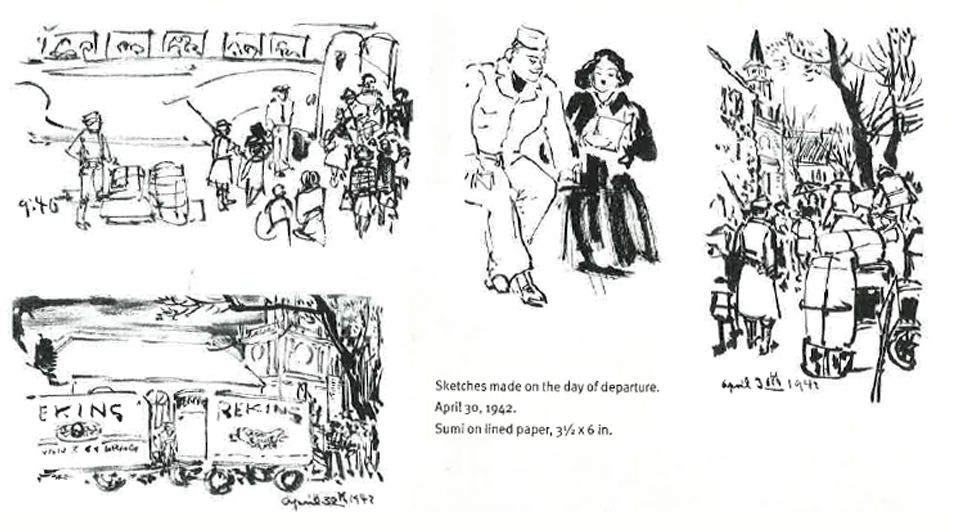

Obata too. He painted as the buses came to take Berkeley’s Japanese to the camps.

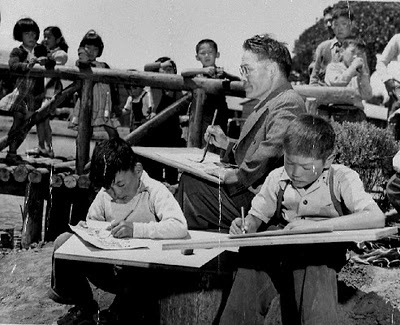

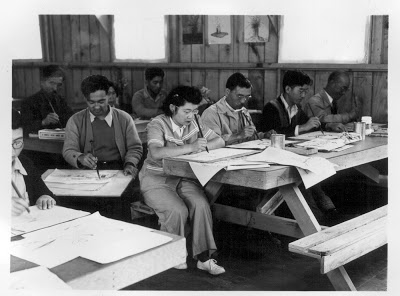

He made and taught art throughout his internment.

He was first interned at the Tanforan Assembly Center at the Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, California, He taught art.

He was trasnferred to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Millard County, Utah.

He taught art there too.

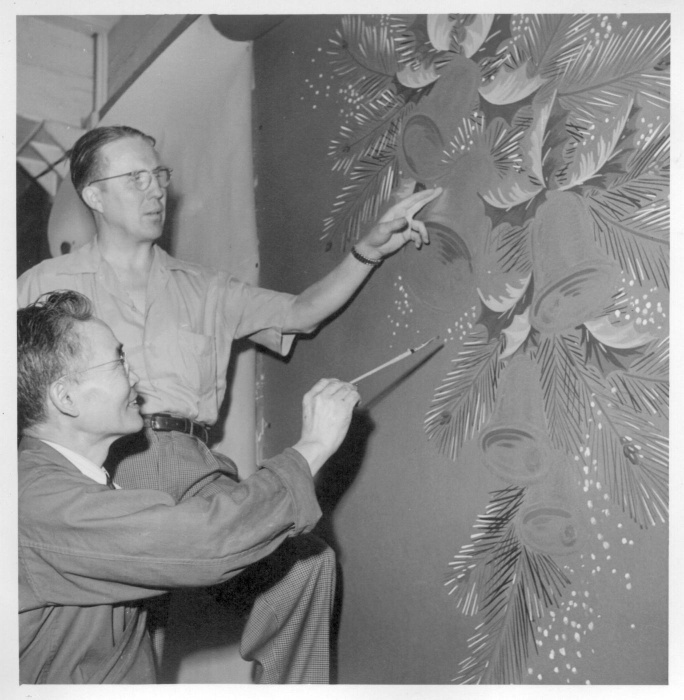

After being released from internment, Obata lived in St. Louis. Above he is shown at the Grimm Lamback Artificial Flower Company. Below he is with his family in their Missouri home.

Obata returned to Berkeley and was reinstated as a professor when Executive Order 9066 was lifted in 1945.

H. L. Dungan,the Oakland Tribune‘s art critic,t ook Obata in and let him stay in his Oakvale Avenue attic apartment. In 1950 Obata bought the house on Oregon.

The Telegraph Business Improvement District has recently honored Obata with a mural on the PG&E substation roughly across the street from his old studio.

It is for the most part in the spirit of Obata’s nature painting,although the fence and guard tower of an internment camp creep into the mural on the left.

Obata was a gifted artist who showed grace and dignity and courage during his internment. And I surely love his depiction of Sather Gate at dusk.

Pauline Kael lived at 2419 Oregon from 1955 until 1964. We know Kael as America’s leading film critic for her writing in the New Yorker starting in 1968.

Kael entered Cal in 1936 and left in 1940 without graduating. She bounced around, living a Bohemian lifestyle in New York, San Francisco, and then Berkeley.

She moved to Oregon Street in 1955.

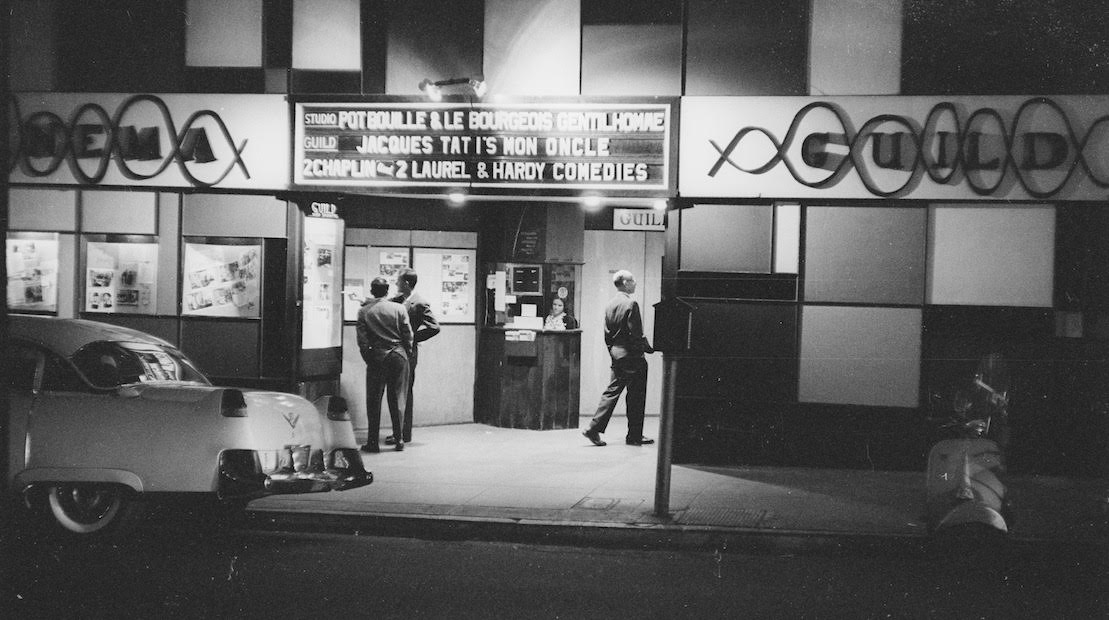

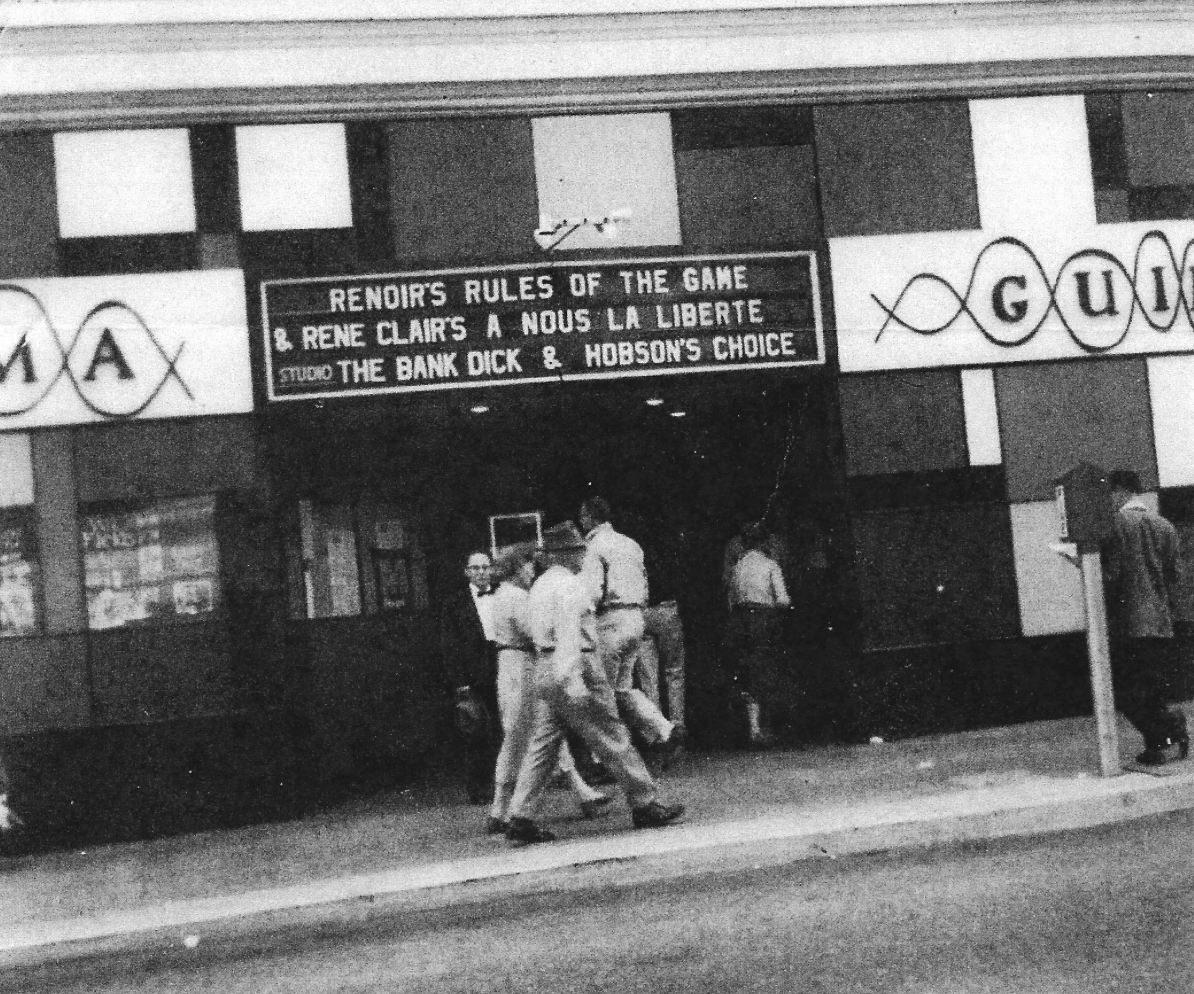

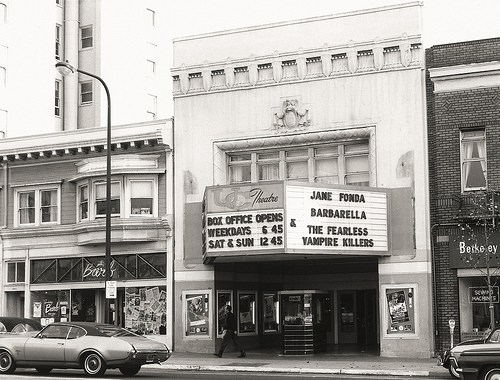

She managed the Berkeley Cinema Guild and Studio, on Telegraph, which showed foreign and domestic art films. Her husband Ed Landberg owned the theaters. She wrote the calendar notes for the films and reviewed movies on KPFA. She was blunt and caustic and very popular.

She managed the Berkeley Cinema Guild and Studio, on Telegraph, which showed foreign and domestic art films. Her husband Ed Landberg owned the theaters. She wrote the calendar notes for the films and reviewed movies on KPFA. She was blunt and caustic and very popular.

Kael hosted salons on Oregon Street. David Pollack, a Cal student at the time, described the crowd at the salons: “a long-haired young man playing Chopin brilliantly on a Steinway upright; a slender and somewhat gamin young mathematics grad student who served as Pauline’s secretary and typist; a plump young Stanford prof with a jolly laugh who held forth on Brecht and Marx; a tall, thin, wispy man with nervous affectations whose conversation was all music and art and philosophy; and, on that particular evening, a dark and trimly bearded middle-aged man named Michael, who was introduced as the last surviving Romanoff and dauphin to the throne of czarist Russia.”

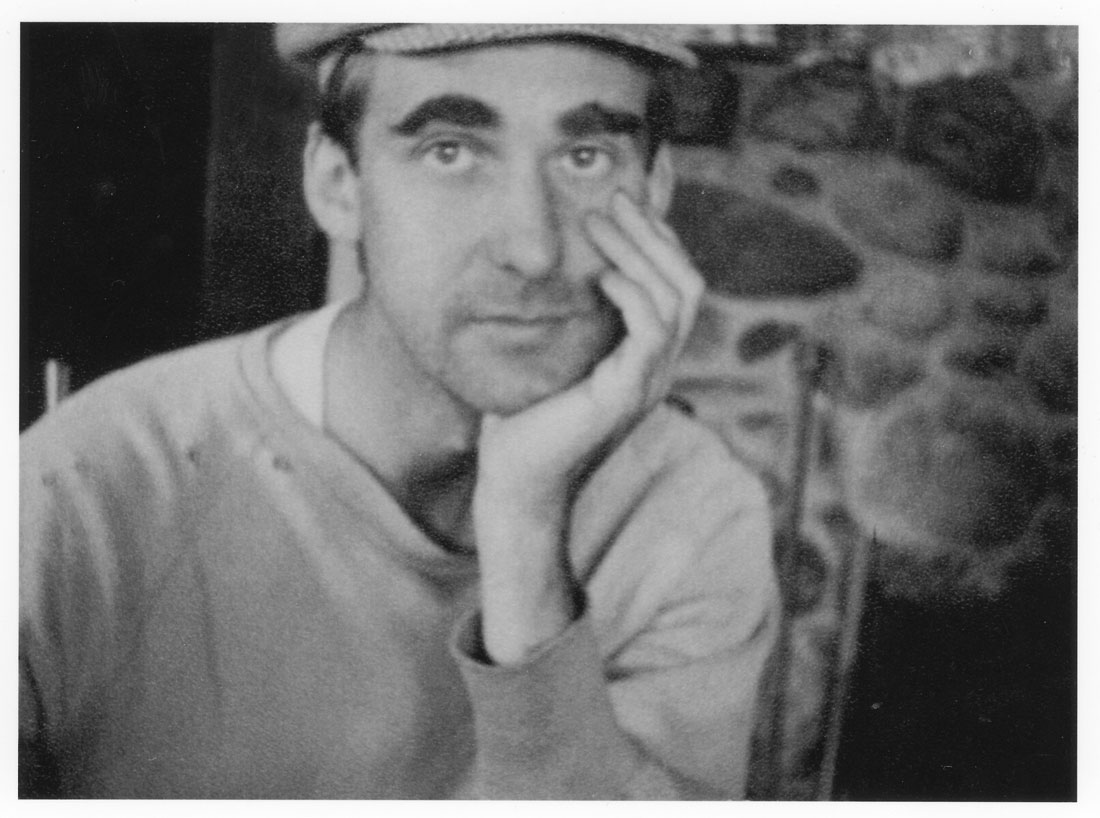

Film maker Jean Renoir was a regular, as was poet Robert Duncan. Pauline Kael and Robert Duncan met in the 1930s as students at Cal. After both dropped out, they kept in touch, confiding in each other about the trials, thrills, and discoveries of life after Berkeley.

With Duncan came Jess (formerly Jess Collins – family fight – last name dropped), Duncan’s partner and an artist. In 1956, Kael hired Jess to paint murals in the Oregon Street house.

He painted 10 murals in the styles of Gaudi, Bonnard, Braque, Klee, the Symbolists, and other. Some of the murals have been painted over.

Another artist, Henry Jacobus, painted the kitchen floor and a mural.

Robert and Ann Basart bought the house in the 1960s and raised their children there. Robert was a composer and a music professor at Cal State-Hayward; Ann Basart, nee Todd, was a publisher and longtime music librarian at UC Berkeley.

In 2016, Reuben Gibson bought the house. He signed a ten-year covenant to preserve the murals, stating that he intended to preserve them as long as he owns the house.

So there you have it – a Bohemain scene with film critic and poet. Berkeley at its Bohemian best, the plate-shifting of the 1960s. And murals to die for.

And then came the 1960s and the Big Changes.

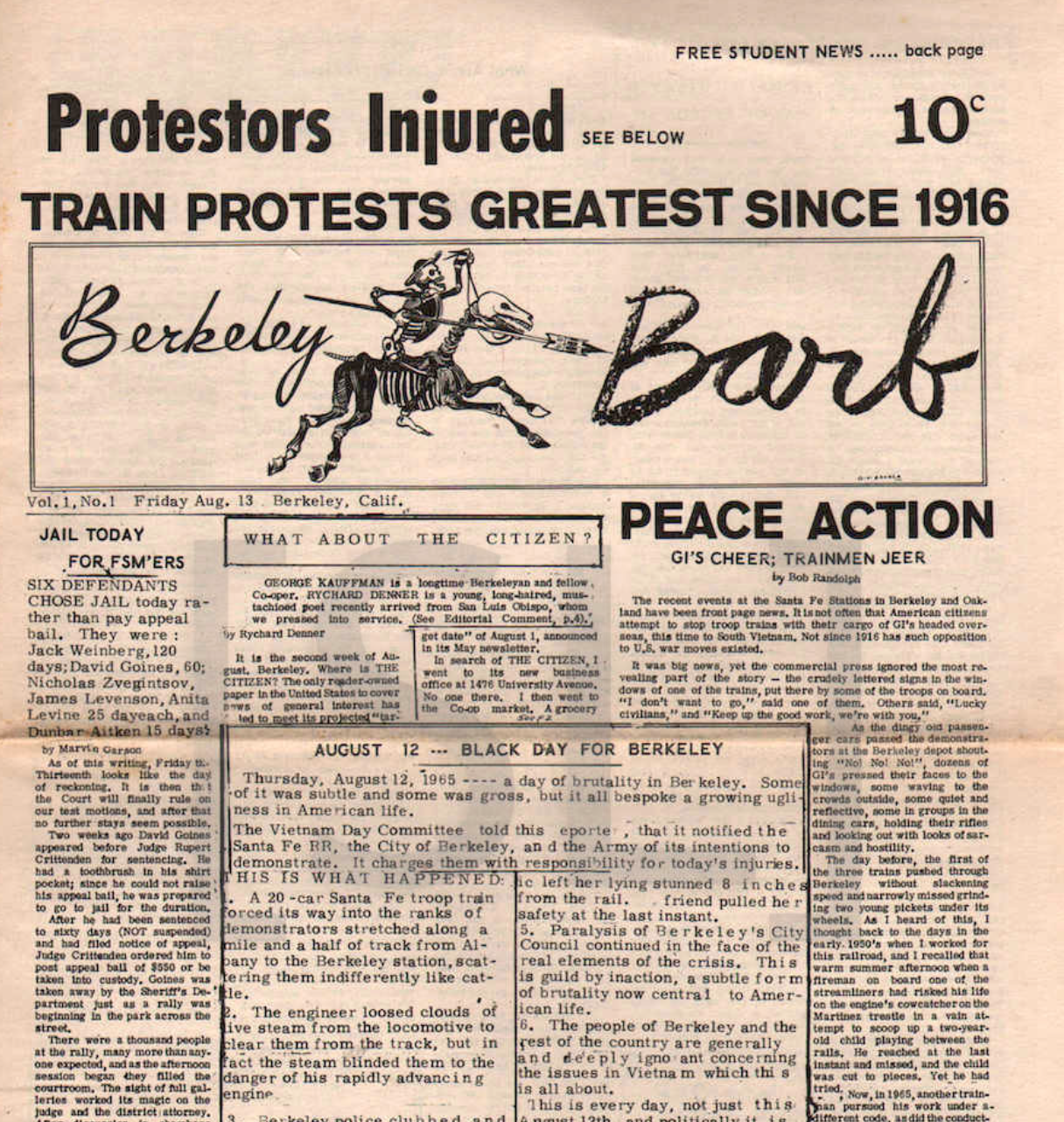

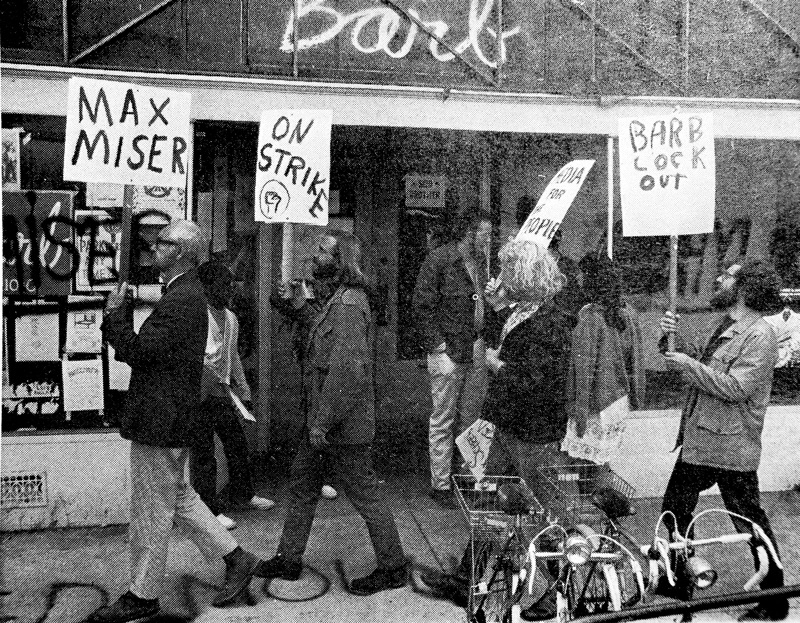

One of the earliest underground newspapers in the United States was our very own Berkeley Barb, which came into being in 1965, birthed by Max Scherr and his counterculture staff. The Los Angeles Free Press had been around for a year at that time, the East Village Other started the same year, and it would be another year before San Francisco saw The Oracle.

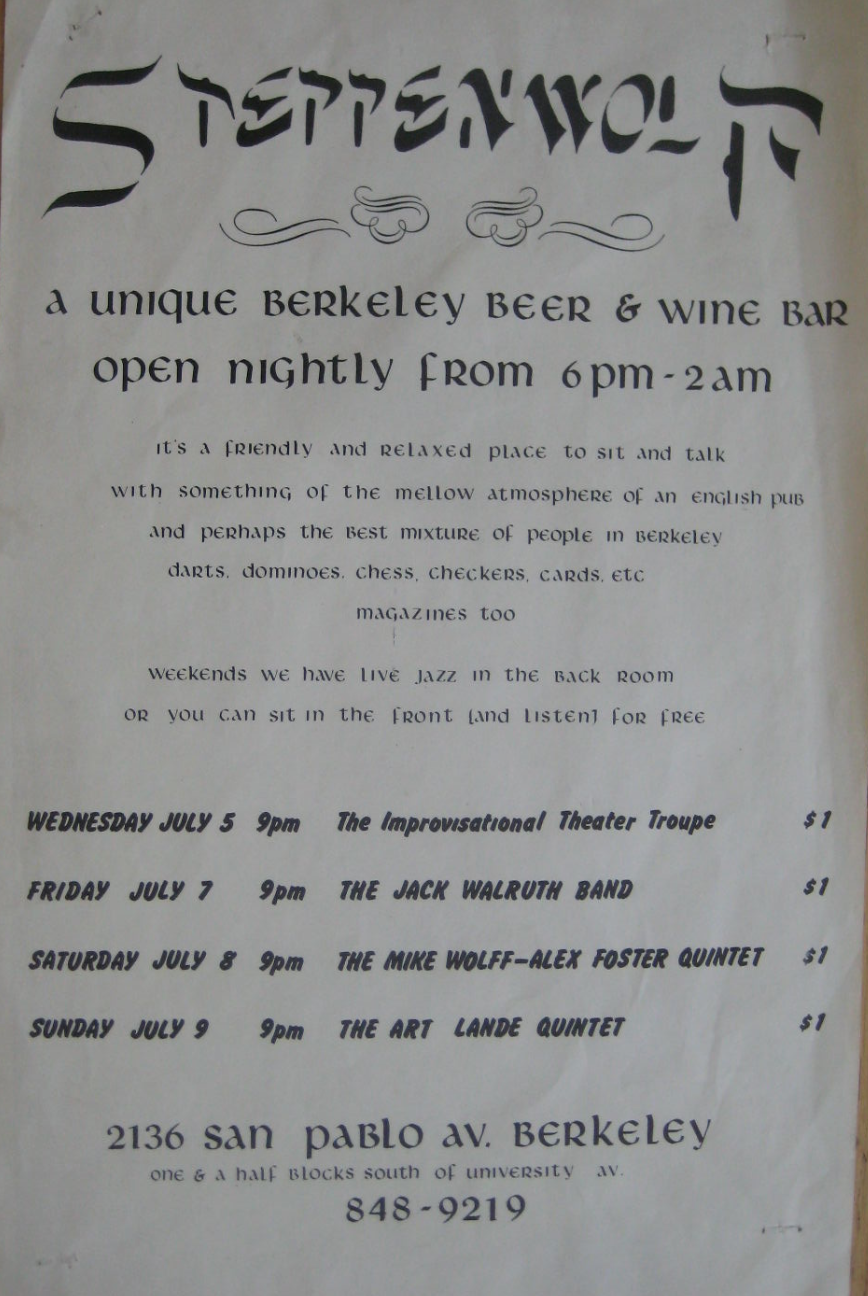

Before launching the Barb, Scherr owned and ran The Steppenwolf at 2136 San Pablo Avenue. It was a coffee shop /folk music club/ beer and wine bar. He owned it from 1958 until 1965.

In 1965, he sold the bar and with the proceeds started the Barb. Scherr had serious Old Left cred. In the years leading up to his launch of the Barb, he was baptized in the fire of the New Left over espresso at Il Picolo (which morphed into the Med) and cheap beer at Robbie’s.

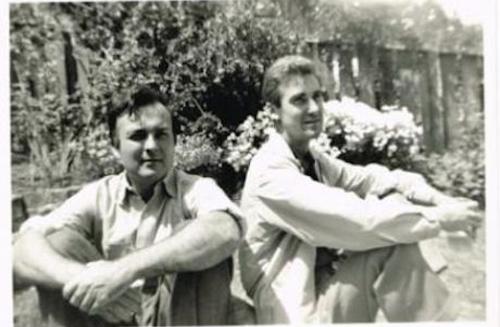

The first issue came out in August 1965. In the early years of the Barb, all business was conducted at Scherr’s home at 2421 Oregon Street.

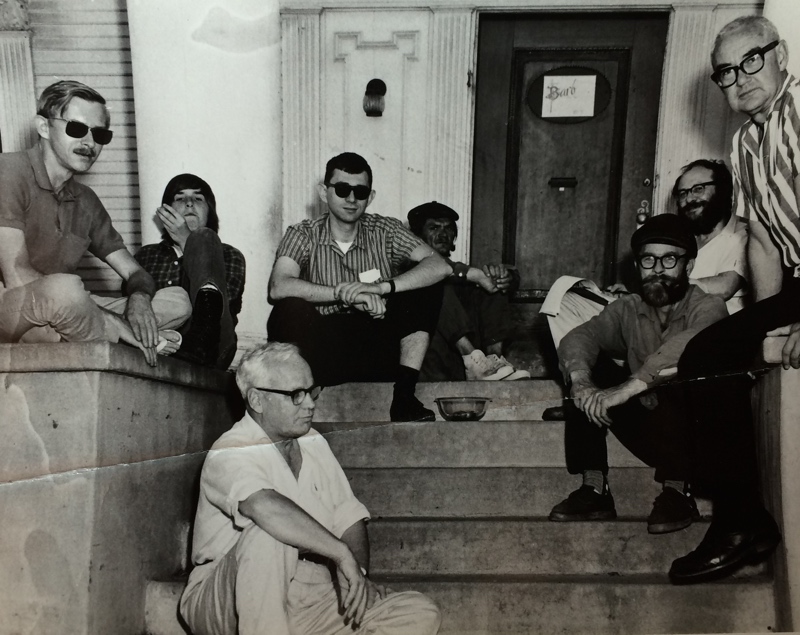

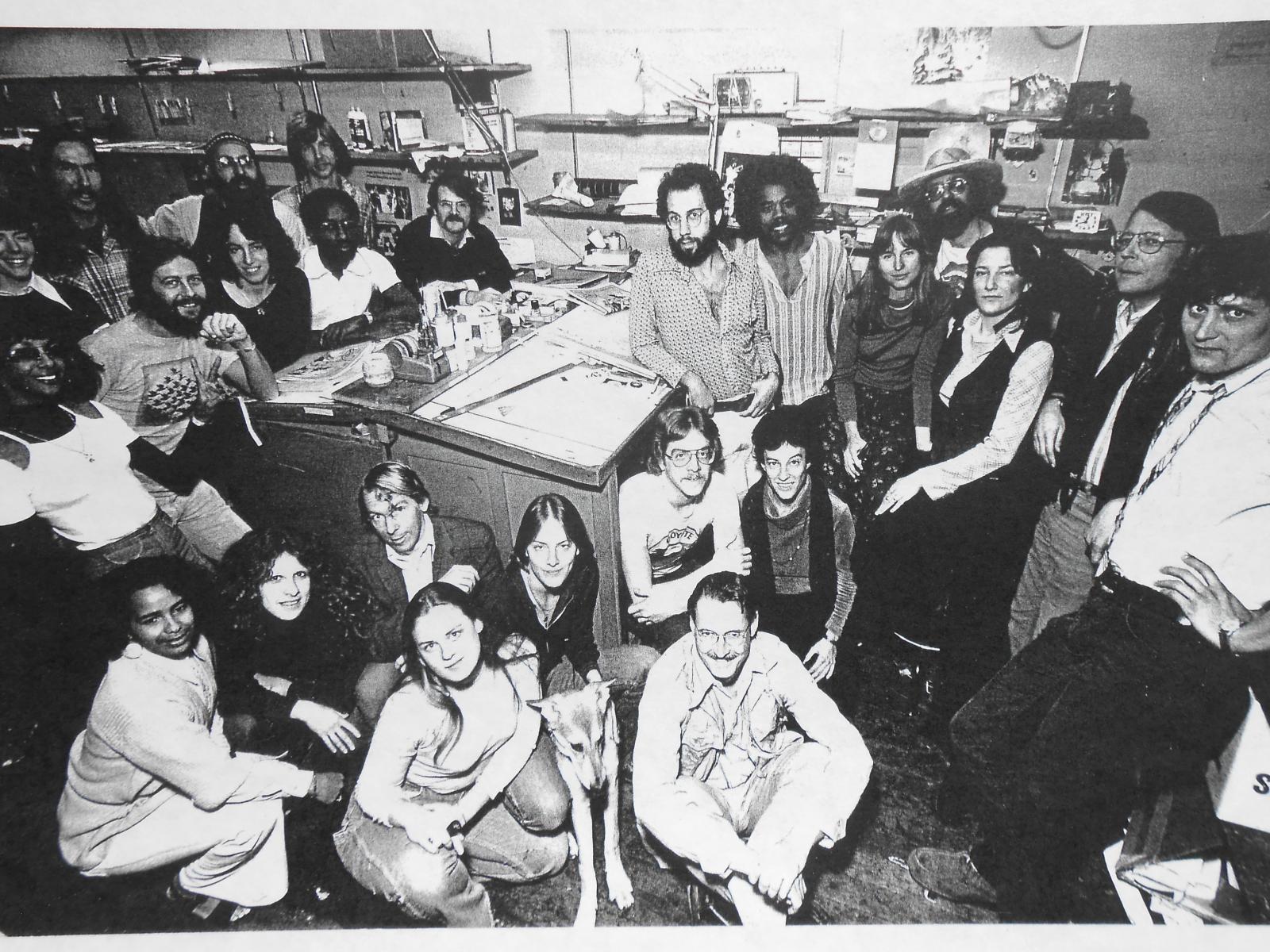

Here members of the Barb staff sit on the front steps.

Barb writer and eventual Yippie Judy Gumbo Albert wrote in On the Ground about the weekly dinner that Max had his partner Jane Peters prepare for Barb staff: ”The house itself looked like a seedy sothern plantation. It had white Corinthian columns and a blue vinyl backseat of a car on the front porch. The kitchen looked like a truck had dumped stacks of mail, newspapers, brown sugar boxes, paper bags, photographs, and an army of bottles all over its chipped black counter. It had a virtual thrift store of dishes, each a different style and color, in the sink or stacked randomly on the oak kitchen table.”

Scherr moved the offices from his kitchen to 2042 University Avenue.

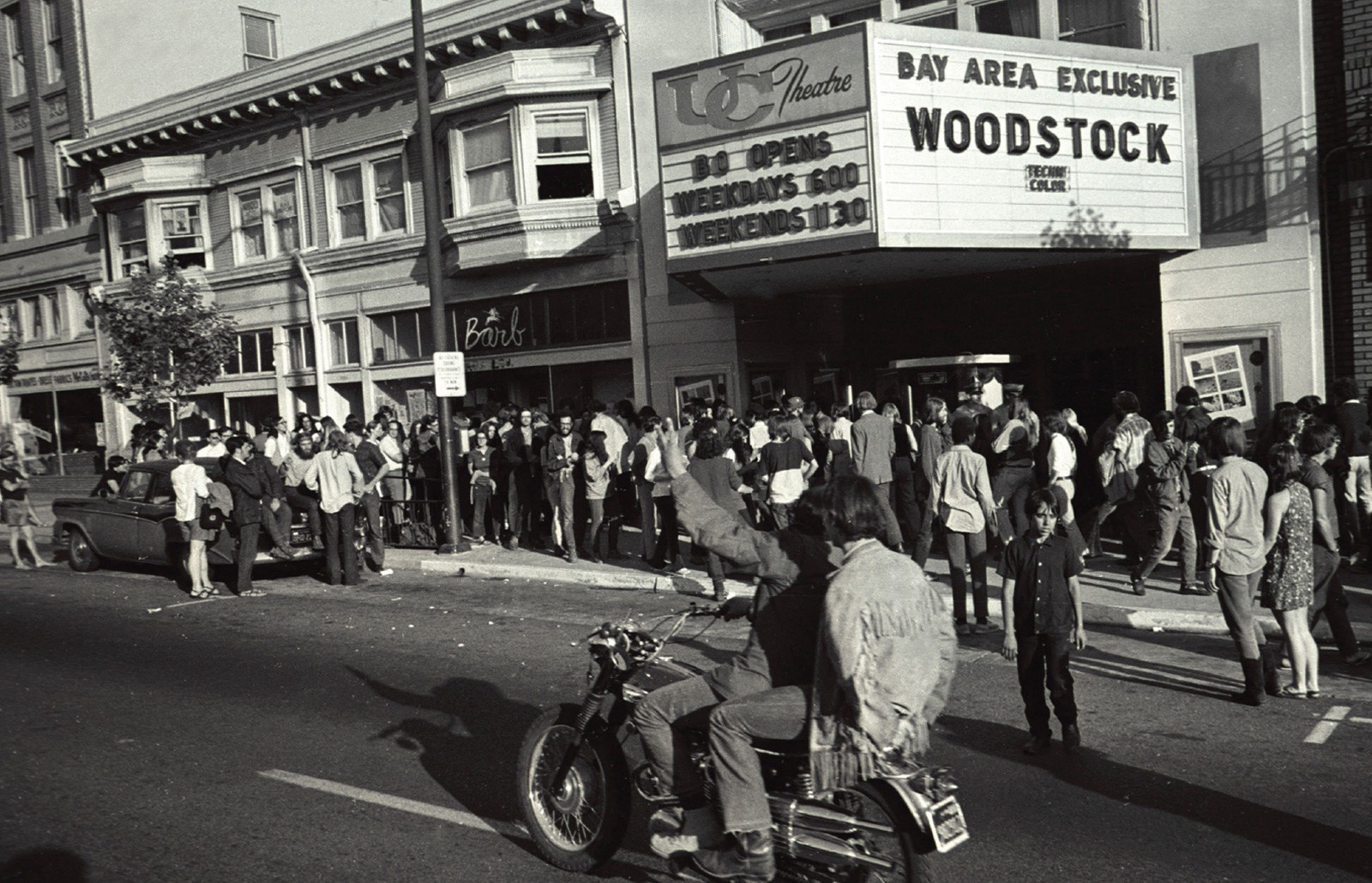

Can you see the “Barb” logo sign just to the left of the theater?

I have found – so far – two shots from the interior. I have seen a contact sheet full of photos of the interior, but they are also filled with naked men and women. Not Safe for Quirky Berkeley!

It is now a Salvadoran restaurant. Pupusas! Kate Harrison had her election night party there. But – if those walls could talk!

So there you have it – Obata’s modest stucco house, Kaen’s lovely Berkeley brown shingle, and Scherr’s colonnaded almost-ante-bellum anomaly. Obata with his watercolors and supreme dignity during internment, Kael with her acerbic criticism and Bohemian salon and Jess murals, and Scherr with his contradiction-laden tip-of-the-spear Barb. All in one block.

If you find yourself depressed about the changes transforming Berkeley and doubt that what we have known and love will survive, I invite you to visit this block and contemplate the creativity and passion and courage of the past. Think about Obata and Kael and Landberg and Jess and Duncan and Scherr and all the bright young leftists who fathered around the Barb – let them inspire. We don’t need to give up yet is what they will tell you.

I showed the draft post to my friend. “I dig those Harry Jacobus kitchen floors. I want! He and Jess Collins and some others opened the Ubu Roi club on Fillmore in 1952. It turned into the Six Gallery where Ginsberg first read Howl.”

Okay – cool enough. but what about the draft post?

I went on a BAHA walk of that neighborhood and recognized Max Scherr’s house as the one where the children’s book author and illusrator Margot Zemach and her four daughters lived in the 80s and 90s. My sister was close friends with her and the interior of the house was quite magical.

So, one more act.