Something there is that doesn’t love a store where gospel music is king.

It’s near the end for Reid’s, 3101 Sacramento.

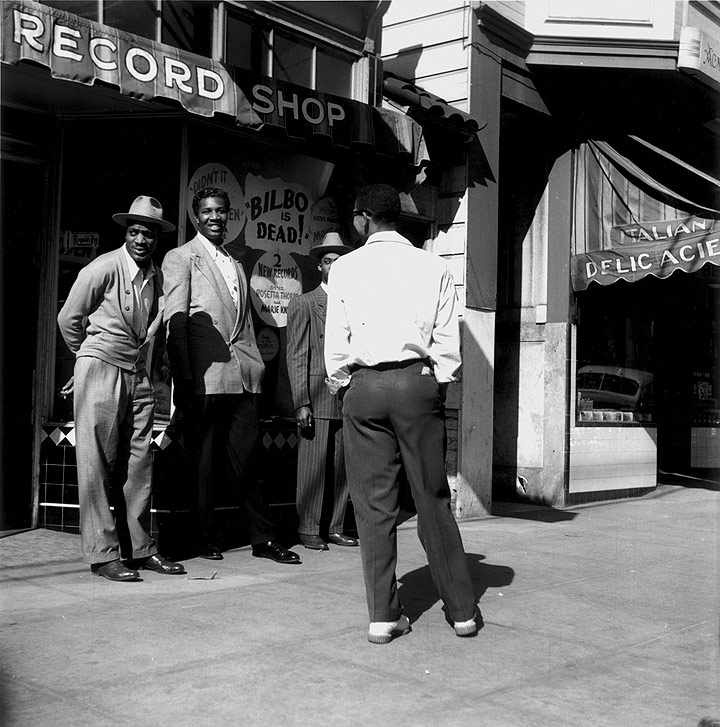

Betty Reid Soskin and her first husband Mel Reid opened Reid’s records in 1945. In the early years, Reid’s didn’t sell gospel, it sold “race records.”

There were only two other record stores in the Bay Area selling Black R&B, Wolf’s in Oakland and Melrose on Fillmore Street.

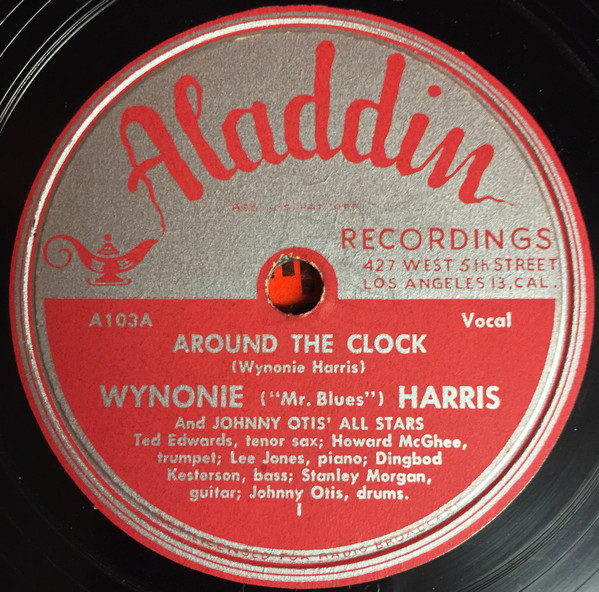

“Around the Clock” by Wynonie Harris with Johnny Otis was a big big hit. Betty said that it was the record that launched the shop.

The shop moved into gospel music when Mel’s uncle Paul Reid started a gospel radio show called “Gospel Gems” that was heard every Sunday. He started promoting gospel shows.

This gave Reid’s an inside track on the gospel record market. Paul also promoted gospel concerts such stars as the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi, Rev. James Cleveland, the Staple Singers, Shirley Caesar, Rev. C.L. Franklin, and the Caravans.

Aretha Franklin was a star of the gospel circuit before she went pop. Reid’s became the outlet for gospel tickets.

Aretha Franklin was a star of the gospel circuit before she went pop. Reid’s became the outlet for gospel tickets.

While writing Damn the Man, I read James C. Scott’s thoughts about the strategies of resistance. His basic thesis is simple – oppressed peoples cannot openly express their opposition to the oppressor, and so their resistance is typically seen in what he calls the “hidden transcript.” In the time of slavery, Christianity became a solace for slaves and, more than that, part of the hidden transcript. The enslavement of the children of Israel in Egypt and then their escape to freedom was a metaphor that slaves could understand.

So it is with gospel music, which evolved as a distinctly African-American hymnody. Black sacred music is at its heart cultural resistance, speaking of exile, strife, hiding, and then of escape to freedom. It is no accident that gospel music played such an integral role in the civil rights movement. For a great read on the role of gospel music in the civil rights movement, I suggest reading “Sit In, Stand Up and Sing Out!: Black Gospel Music and the Civil Rights Movement” by Michael Castellini.

Leaving aside the cultural context, gospel is also plain and simple a beautiful art form that is often self-described as joyful noise, a phrase grounded in the Bible.

Make a joyful noise to the Lord, all the earth; break forth into joyous song and sing praises!. Pslam 98: 4

Oh come, let us sing to the Lord; let us make a joyful noise to the rock of our salvation!. Psalm 95: 1

Make a joyful noise to the Lord, all the earth! Psalm 100: 1

With trumpets and the sound of the horn make a joyful noise before the King, the Lord! Psalm 98: 6

Anyway, gospel music was king at Reid’s and things sailed along for a while. But then came the sixties. Uncle Paul died and times were changing. Mel Reid tried to stay culturally relevant by taking the store towards hippie culture, selling water pipes, semi-erotic black-light posters, and other drug paraphernalia. Betty and Mel divorced, and Mel strayed. In 1978 Betty took over the store when Mel experienced serious health problems. She trashed the hippie stuff and drug paraphernalia that Mel had been selling and took the focus back to gospel, but the glory years were not easily recreated.

The Black exodus from Berkeley had begun. Berkeley’s Black community suffered through the years of the color line, Even after the color line faded, there were powerful public advocates of racial discrimination in housing. When he ran for governor in 1966, Ronald Reagan vowed to repeal the California Fair Housing Act of 1963, better known as the Rumford Act, a significant and sweeping law protecting the rights of Blacks and other people of color to purchase housing without being subjected to discrimination. Reagan argued that “If an individual wants to discriminate against Negroes or others in selling or renting his house, he has a right to do so.”

Neither the color line nor Reagan’s open and notorious racism drove Blacks from Berkeley – other forces did. Much of the central business district of Black Berkeley was annihilated with construction of the Ashby BART station and parking lot. Then came the crack cocaine epidemic. And now – gentrification is destroying the African-American community. The Adeline Corridor is Ground Zero for yuppie gentrification in Berkeley with enthusiastic support from Berkeley’s new conservative, pro-developer City Council.

BART, crack and gentrification have had their effect, accomplishing what Reagan’s racism could not – a Black exodus.

In 1970, 27,421Bblacks lived in Berkeley – 23.5% of the population.

In 2000, 14,007 Blacks lived in Berkeley – 13.6% of the population.

In 2010, 11,241 Blacks lived in Berkeley – 10% of the population.

In 2019, 10,284 Blacks live in Berkeley – 8.6% of the population.

That means that Berkeley has lost 62% of its BFlack population since 1970.

With the loss of Berkeley’s African-American population and community, the gospel music scene has all but disappeared. And Reid’s has withered. It will close in October.

There is a melancholy in the store. I felt it at the Med and Cody’s and at Brennan’s in their final weeks. It hangs in Reid’s.

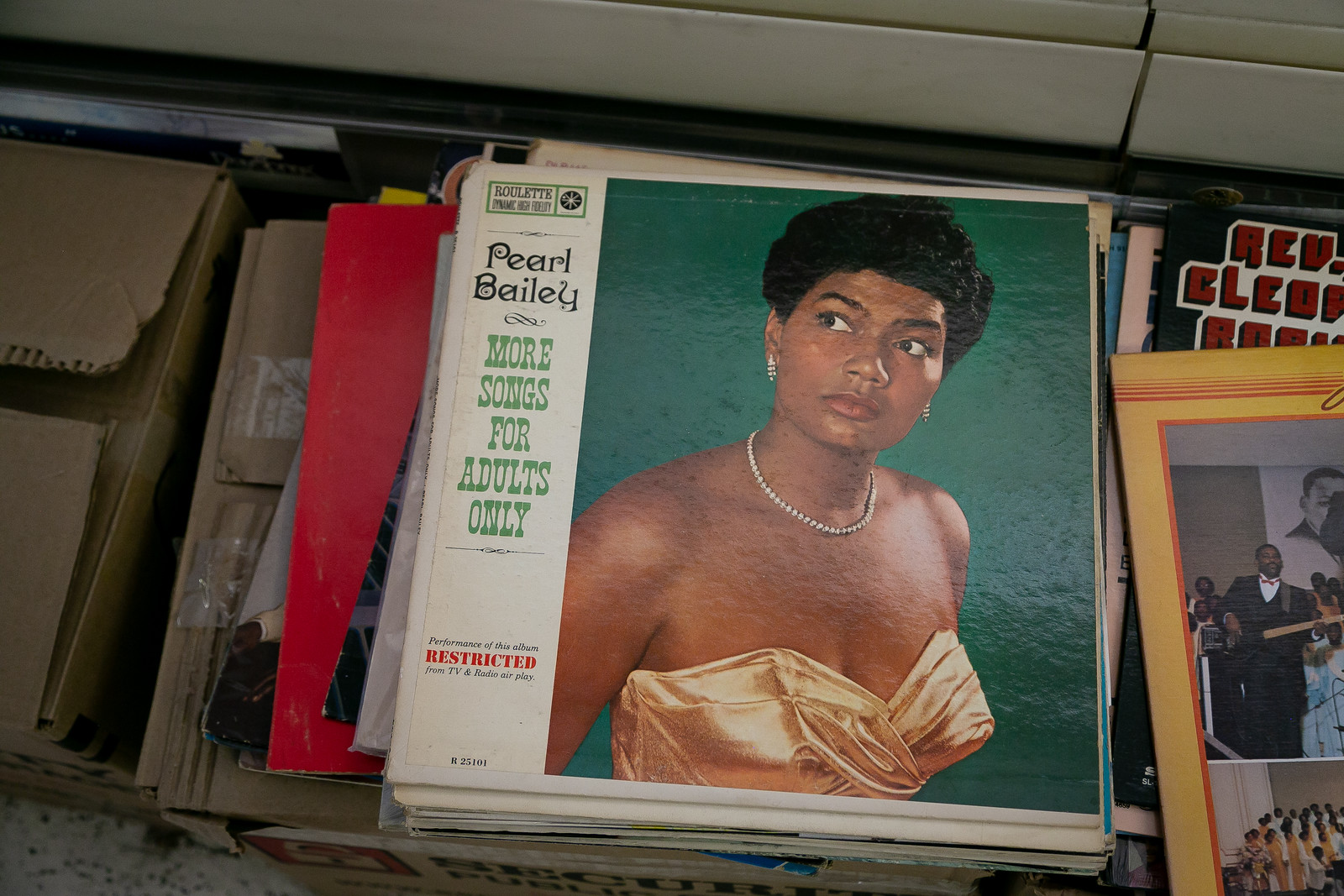

But the records are still there.

Most of the albums are gospel music, but not all. Some of the tracks on this Pearl Bailey album – “There’s a Little Bit of Bad in Every Good Little Girl,” “The Great Indoors,” “Love for Sale,” and “One Man is Good Enough for Me.”

For me, Reid’s choir robes section is the portal into the joy and pageantry of the black church.

There are Bibles and religious literature and church supplies.

These hymn boards take me back to my boy days, when I attended a service of morning prayer five days at week at school and then church on Sunday. I knew the Episcopalian hymnal well and checked the hymn board when I got to the pew.

In these, the end times of Reid’s Uncle Paul Reid watches over the store.

Loved reading this post, Tom. Back on the Main Line my parents had hired a woman to clean our home every few weeks, and I remember hearing gospel broadcasts on the radio while she worked, all the shouting and all the joy, the pounding piano and massed voices in chorus. Besides the rousing morning chapel sing-alongs at EA, were you taught spirituals in Lower School? I remember “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” and “Swing Low” and “Were You There?” — now, thanks to you, I’m trying to decode their “hidden transcripts.”

I don’t know nothin’ about Jesus, but I always loved gospel music, the energy, the passion, the music, and even the words. The lyrics were good too sometimes. Mostly it was the soul I guess.

While waiting at the station

For the train Tomorrow to come

It can seem forever to arrive

But rest assured it will show up

Not always on time

And you do not know what it will look like

Nor who will be it’s engineer

Thanks, Tom. M

Thanks for this wonderful post, and for all the ways in which you enrich our sense of Berkeley. Quirky Berkeley is my map for discovering the most interesting people and places, often fast-disappearing from our midst. I love this take on gospel and its role in the African-American community, and am sad to see Reid’s fade away.