In 1957, history doctoral candidate Ralph Shaffer became the first student at Cal to step from the silence and shadows of the fifties. McCarthyism had driven a generation of Cal Students away from the political activism that comes naturally to the young. Shaffer made a modest proposal to the student government executive committee, that fraternities and sororities be prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race. His attempt failed in the short term.

Small causes can have larger effects. After the “Shaffer Bill” came TASC, and then SLATE, and then the HUAC riots, and then the Free Speech Movement, and so on. Ralph Shaffer was that small cause.

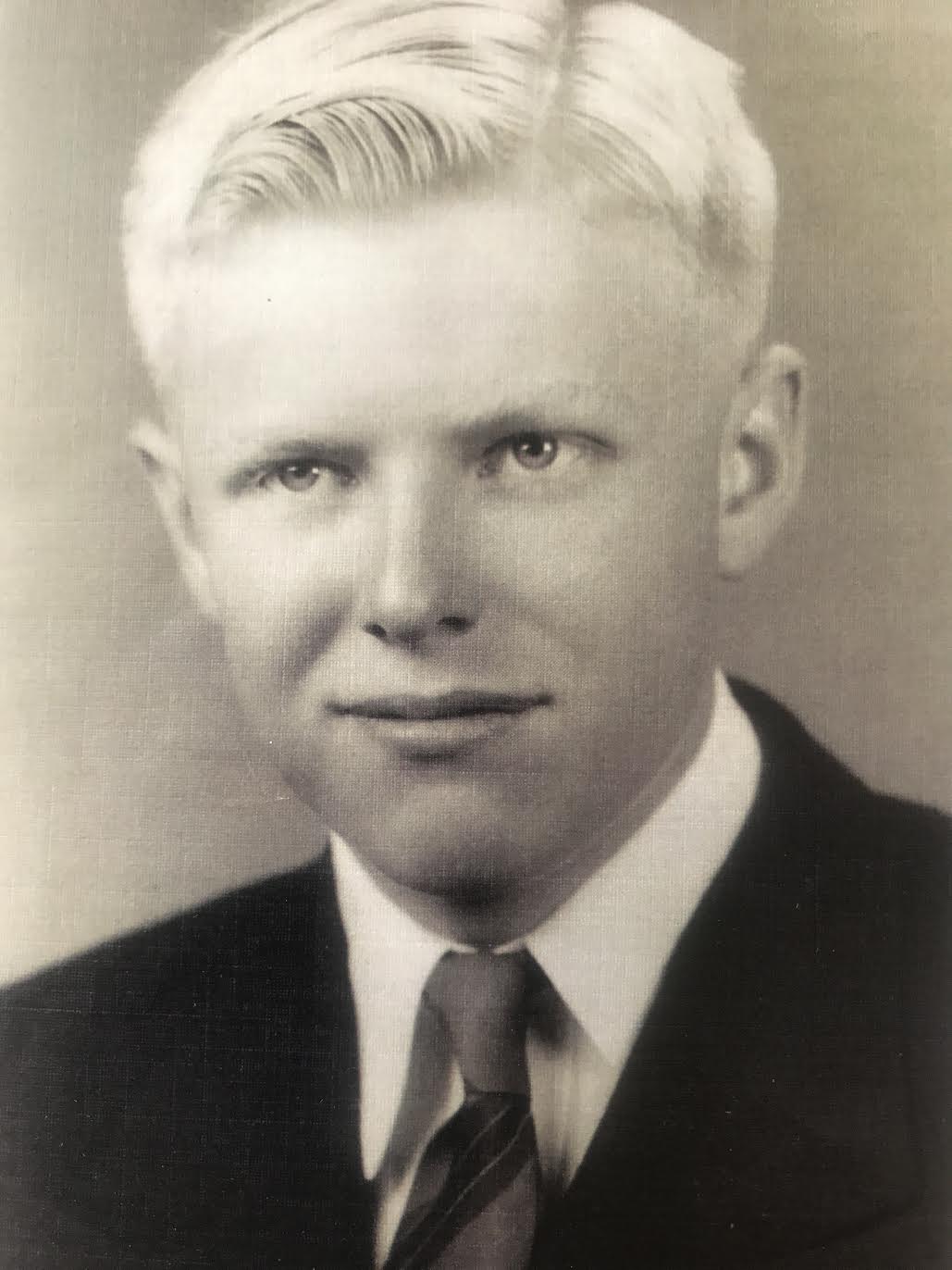

Shaffer was born in Fresno in 1930. He grew up in Long Beach, the son of conservative Republican parents.

When he matriculated at UCLA in 1947, he was still relatively conservative. That changed at UCLA..

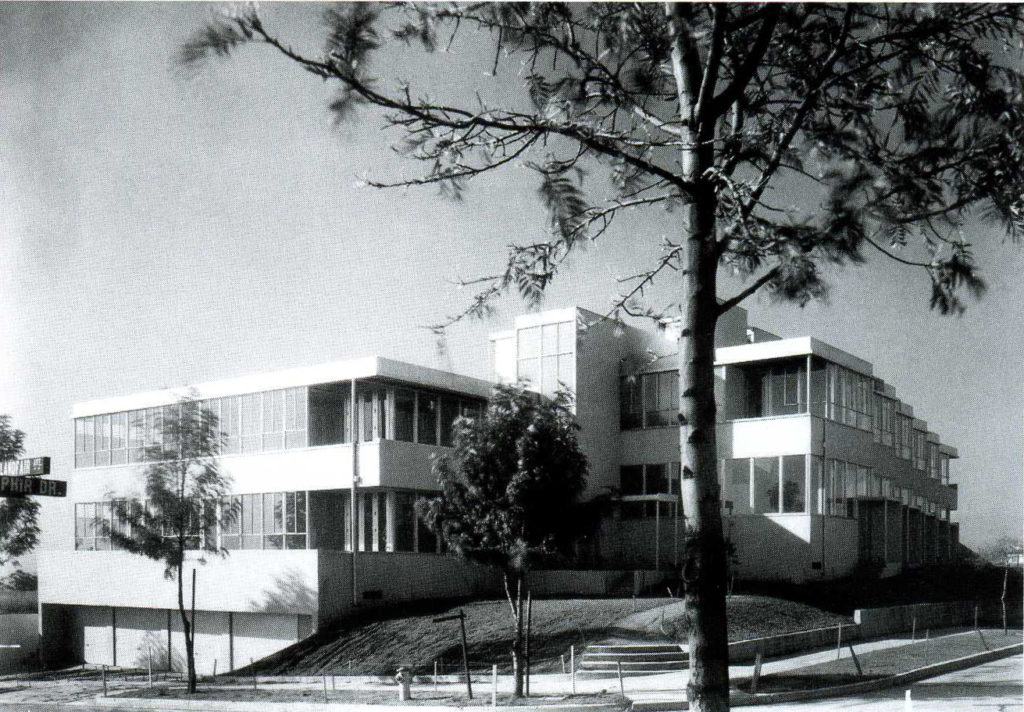

He took residence in the University Cooperative Housing Association. One of the Co-op housing residences was Robison Hall. Robison Hall was designed as the Landfair Apartments by Richard Neutra. That’s no small thing.

Shaffer lived near, but not in, Landfair. “I lived in The Prefab, a surplus WWII one story barracks with eight bunk beds to accommodate the 16 of us living there. The Prefab was located on the back of the lot at 500 Landfair, across the street from Robison Hall, which was on Ophir, at the corer of Landfair.” Almost a Neutra, but a barracks instead.

In the Co-op, most of the members were Democrats, but he also met and learned from members of the Progressive Party, the Communist Party USA, socialists, and anarchists. He wasn’t sure that there was much daylight separating the Wallace supporters and the CPUSA.

What about the CPUSA did not appeal to Shaffer? “I am a socialist of the heart, not the head, With a minor exception, the only Marx I ever read was part of the Communist Manifesto. I don’t recall reading anything by Lenin. Nor was I into Schachtman, Trotsky or any other faction of the socialist-communist movement. I didn’t like the democratic centralism of the CP. I wasn’t about to support a position I thought was wrong. Like so many other American socialists, I was drawn by the humanity of socialism, not the barricades.”

I asked Shaffer what his conservative parents thought of their newly radicalized son. “My socialism was not a class struggle socialism but was more of a Christian socialism, although I’m an agnostic. I think my parents became much more liberal as a result of my living with blacks, Jews, Muslims, etc at the co-op at UCLA.”

The UCLA campus was alive with leftist ideals and principled people.

Photo: UCLA University Archives, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California 90095-1575;

John Caughey was an inspiration to Shaffer. Caughey, not a leftist, had refused to sign the State’s Loyalty Oath as a matter of principle. Shaffer: “I knew John Caughey as well as an undergrad could. Had he not been dismissed because of the loyalty oath, I would have done grad school there at UCLA with him. He was the specialist in California and the West, which was my grad school field. Instead, I went to Berkeley and worked with Dr. Lawrence Kinnaird. I hitchhiked to San Francisco in August, 1950, to attend the meeting where the Regents were to vote on the oath and Caughey spoke against it. Caughey later gave me a copy of his speech to the Regents. At that meeting, the vote to adopt the oath failed by a single vote. Regent Neylan changed his vote from nay to aye so that he could then move to reconsider, which he did, and in September, with the votes of some member or members who were absent from the August meeting, the oath was

adopted.

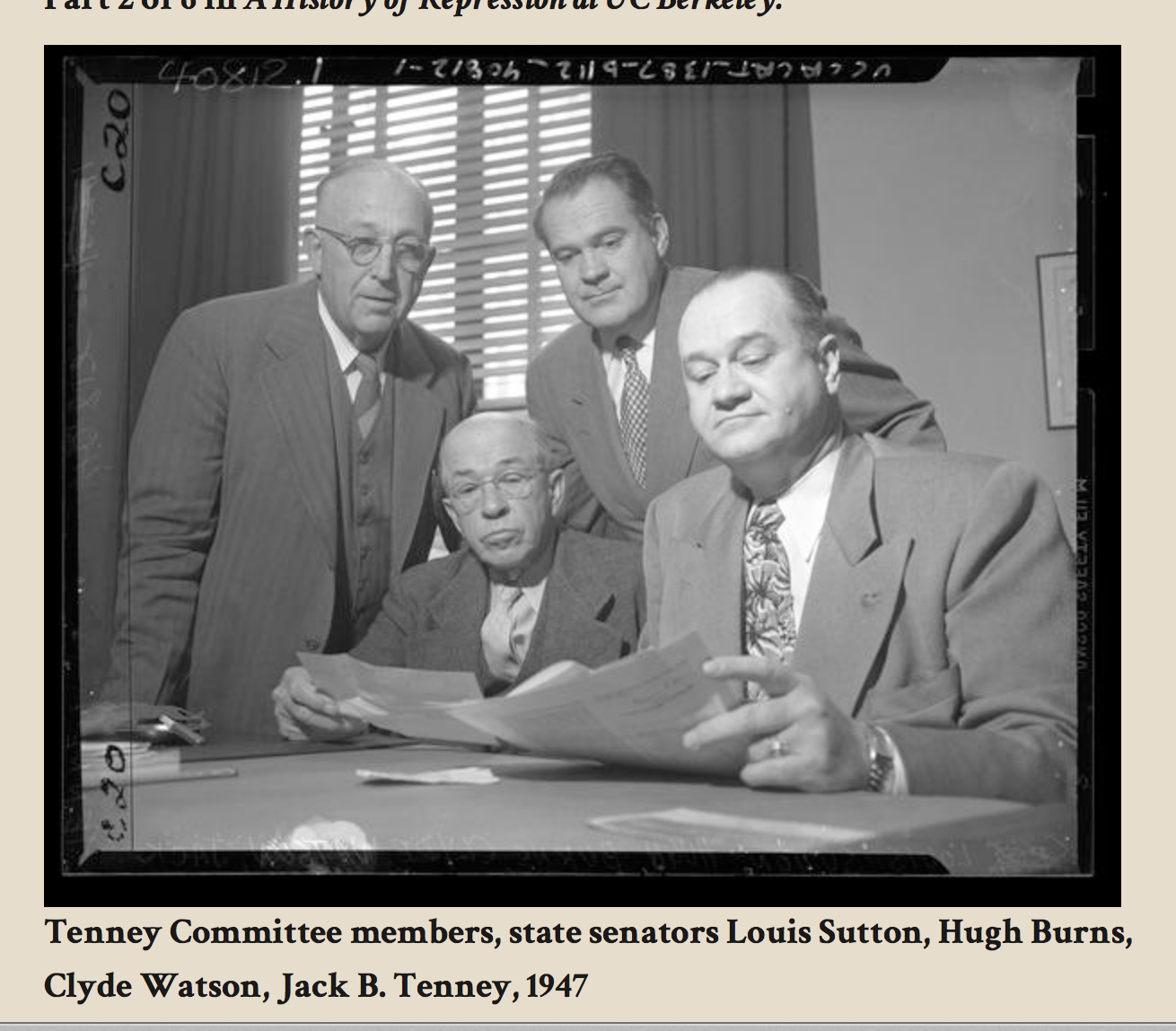

The state legislature had considered the loyalty oath, especially Jack Tenney, a fervent anti-communist. The Regents headed off legislation by imposing the oath themselves.

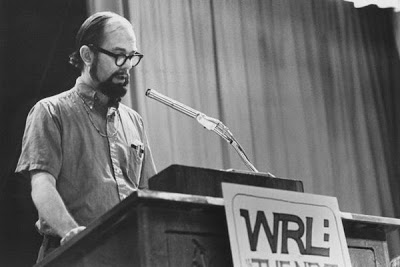

David McReynolds addresses a gathering of the War Resisters League, where, on the recommendation of Bayard Rustin, he worked late in his career, until his retirement in 1999. (THE NEW PRESS)

Dave McReynolds was a friend and inspiration. In 1951 McReynolds joined the Socialist Party of America and in 1953 he graduated from UCLA with a degree in political science. McReynolds had strong religious objections to the Korean war and avoided prison

that way.

McReynolds has spent his working life with the War Resistors League and in socialist organizations. On November 6, 1965, he and four other men burned their draft cards at an anti-war demonstration in New York, one of the first public draft-card burnings after federal law was changed on August 30, 1965 to make such actions a felony,

Vern Davidson was another UCLA socialist. He resisted the draft, was arrested, and was sentenced to three years in jail.

He served two of the three years. When he was released, he came back to UCLA and enrolled in the Law School. The university told him that as a felon he couldn’t become a lawyer so there was no reason to enroll in Law School. Vern replied that if he failed, the matter would be moot, but it he graduated, the matter could be taken up then. He graduated.

He heard the same thing when he applied to take the bar. He was told that there was no point in his taking the bar exam, since as as a felon, he could never be admitted to the bar. Vern said “Let’s find out – if I fail the bar exam, the matter will be moot – and if I pass it, we can see.” He passed and in the end a special sub-committee of the state legislature met and agreed to admit him to the bar. Davidson became the Dean of Law at Gonzaga after teaching in Africa for a time.

This essay in memoriam of Davidson gives a great sense of what it was to be a young socialist in Los Angeles in the early 1950s.

Shaffer was drawn to and joined the Socialist Party of America, led by Norman Thomas. Thomas hoped to make the anti-Stalinist left the leader of social reform, in collaboration with labor leaders like Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers. Racial discrimination was a core issue for the SPA..These were dark and difficult times for socialists, but the idealism and vision appealed to Shaffer.

Oakley’s Barber Shop was in Westwood Village, near the UCLA campus. They would not cut the hair of an African-American member of the housing co0p.. Shaffer and others picketed and entire summer of 1948.

Shaffer: “I met with Oakley late in the summer of 1948 as we tried to get him to change his policy. He insisted that he was not prejudiced. He even pointed to the book about Jackie Robinson that he had on his desk, He suggested that a solution might be to set up a barber chair in some other building in Westwood for the convenience of blacks, who otherwise had to go to Santa Monica for a haircut. There were excuses for not changing his policy – barbers didn’t know how to cut blacks’ hair, the attitude of his customers, and perhaps others that I can’t recall.” Oakley’s policy did not change until years later.

Shaffer graduated from UCLA a history major in 1951 and came to Berkeley for graduate studies. He wasn’t here long – in the spring of 1952 he was drafted.

Shaffer spent two years in the United States Marine Corps. Korea? Nope. He played the baritone horn, a low-pitched piston-valve brass instrument in the saxhorn family, in the Marine Corps band. He was stationed at Camp Pendelton. The band regularly played for troops departing from San Diego for Korea.

He returned to Berkeley for graduate work in 1954. What was the biggest change in those two years?

The Inkwell was gone. When Shaffer left in 1952, there were two locations – Inkwells – on campus where students could fill their fountain pens. In 1953,Waterman introduced moulded plastic fountain pen cartridges that were immediately successful and popular. When Shaffer returned in 1954 the cartridge fountain pens had taken over and the Inkwells were gone. That was about it for change.

The Berkeley campus was politically quiet – even silent – compared to UCLA.

Loyalty Oath protest April 10 1950. Photo: The San Francisco News-Call Bulletin newspaper photograph archive, Bancroft Library

In 1950, there had been protests against the University’s proposed loyalty oath.

Chaucer scholar Charles Muscatine refused to sign the loyalty oath and was fired. He said: “I felt that in the first place it was a violation of the oath to the U.S. Constitution that I had already taken. And secondly it was a violation of academic freedom, which is the idea that in a free society scholars and teachers are allowed to express and believe anything that they feel to be true. As a young assistant professor, I had been insisting to the kids that you stick to your guns and you tell it the way you see it and you think for yourself and you express things for yourself and I felt that I couldn’t really justify teaching students if I weren’t behaving the same way. So I simply couldn’t sign the oath.” He was fired, vindicated in court in 1951, and reinstated in 1952.

After a slight flurry about the loyalty oath, when Shaffer returned from the service In 1954, the silent generation was silent in Berkeley.

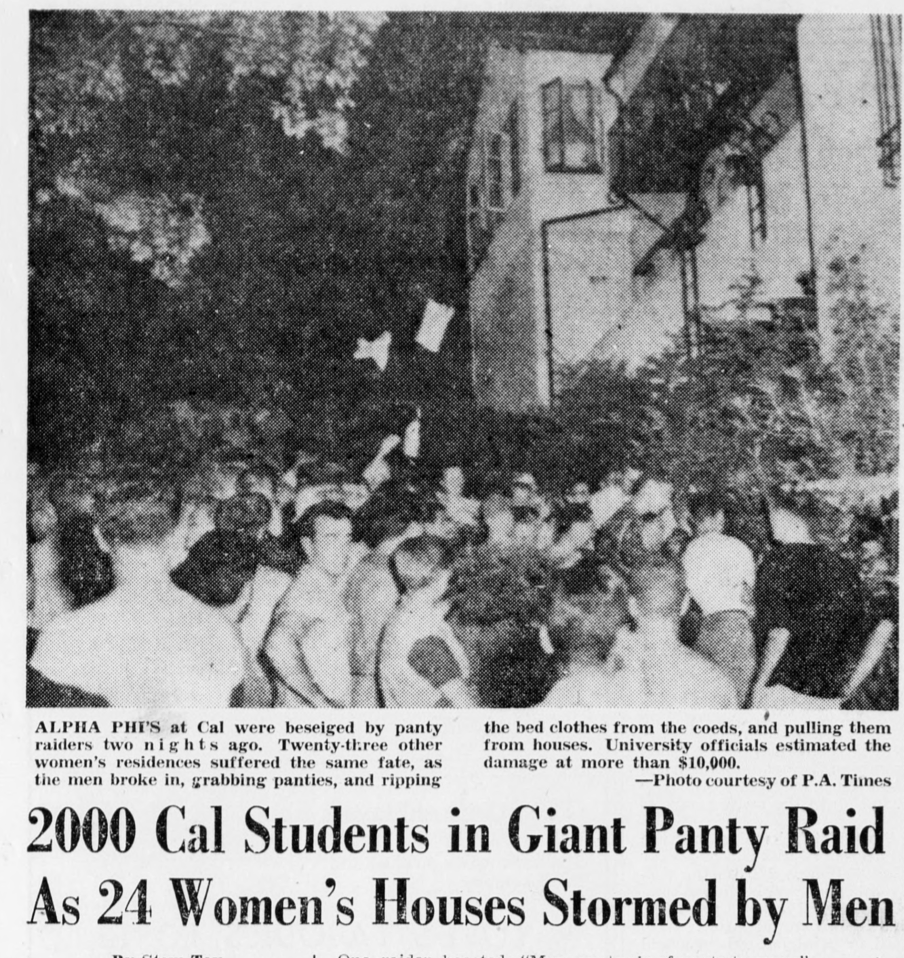

Was it completely quiet? No. In May 1956, several thousand Berkeley students rioted for seven hours, battling police as they rampaged and caused tens of thousands of dollars of damage.

It has been said that “At a number of colleges, panty raids functioned as a humorous, ad hoc protest against curfews and entry restrictions that barred male visitors from women’s dormitories.” Another way of looking it would be that they were good clean fraternity sexual assault fun.

Shaffer got his masters degree in 1955. His thesis was on “The Socialist Party of California.” Although a socialist, he did not belong to the Socialist Party in Berkeley.

He did, however, put together a great library of socialist writing thanks to the used bookstores of Telegraph Avenue. He still has the books at his home in Covina. Books!

In October 1956, Shaffer was chosen to fill the vacant graduate student spot on the student government executive committee.

He went to work right away.

Regulation 17, which prohibited political activity on the campus, was of concern.

Hank di Suvero, who lived at one of the Berkeley student co-ops and was on the Executive Committee the year that Shaffer served, was interested in working on that issue. He was also active in the effort to make ROTC voluntary. He and Shaffer wrote Chancellor Clark Kerr on December 16, 1956, challenging the fact that the University had allowed pro-ROTC literature to be distributed on campus and in classrooms while denying the anti-mandatory-ROTC students the right to circulate their pamphlets. In 1957, Regulation 17 was eased: the stipulation that both views of any controversy be presented was removed, and ASUC approval of meetingsand speakers was no longer required. The rest of Regulation 17 stayed intact, waiting for the Free Speech Movement.

Di Suvero went on to be very active in civil liberties organizations, the civil rights and anti war movements. He served as the President of the National Lawyers Guild, and was the principal organizer of a night law school in Los Angeles, The Peoples College of Law. He worked for nine years as a lawyer in the black ghetto of Los Angeles before leaving America in 1979.

Back to 1957 – Shaffer had another issue in mind – racial discrimination by fraternities and sororities. Fraternities and sororities played a more important role then than they do now because there were almost no dormitories on campus. As Shaffer remembers, the only university housing for students was Bowles Hall for men and at the top of Dwight Way, the Smyth-Fernwald buildings, designed by Walter H. Ratcliff Jr. in 1945 as “temporary” housing for married students. Which meant that in a supply-demand housing world, fraternities were more important.

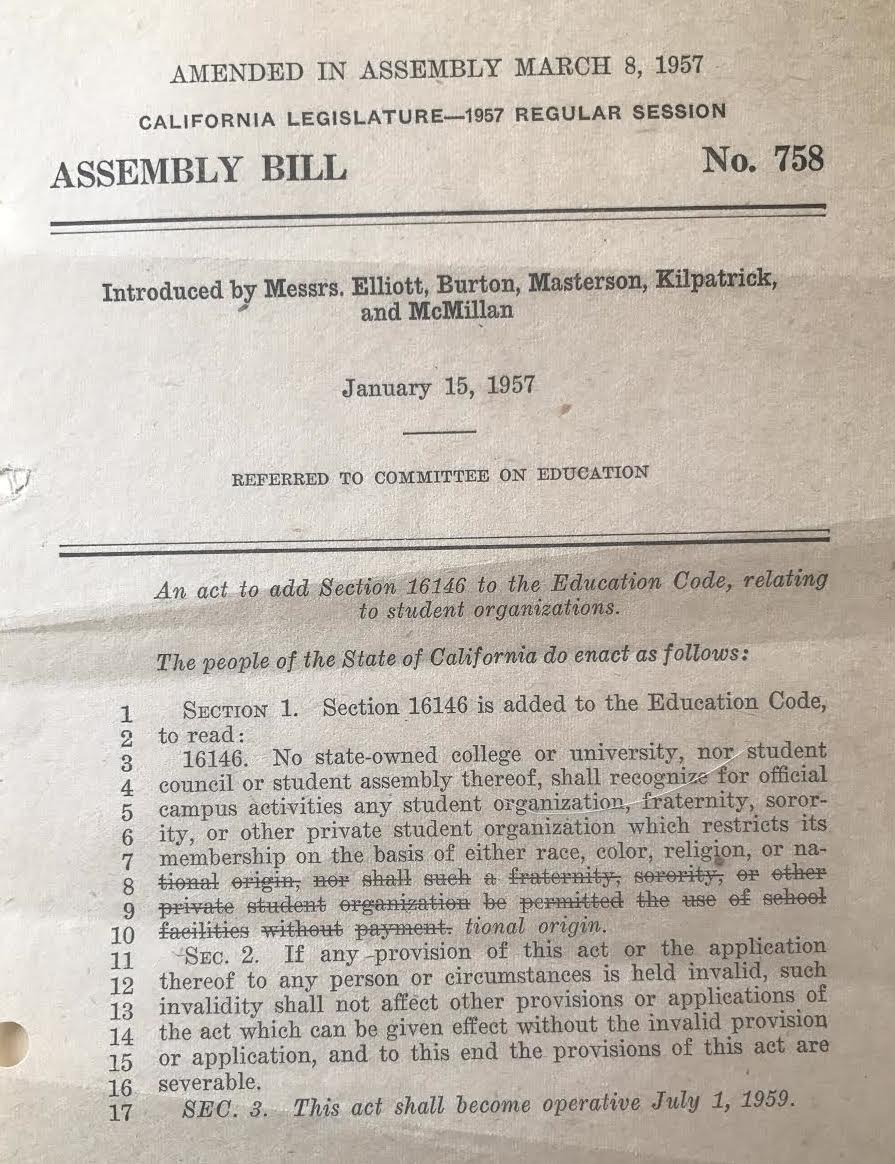

On January 15, 1957, Assemblyman Edward E. Elliott from East Los Angeles introduced Assembly Bill 758.

It prohibited recognition of any student organization “which restricts membership on the basis of either race, color, religion, or national origin.” The bill stalled in the legislature.

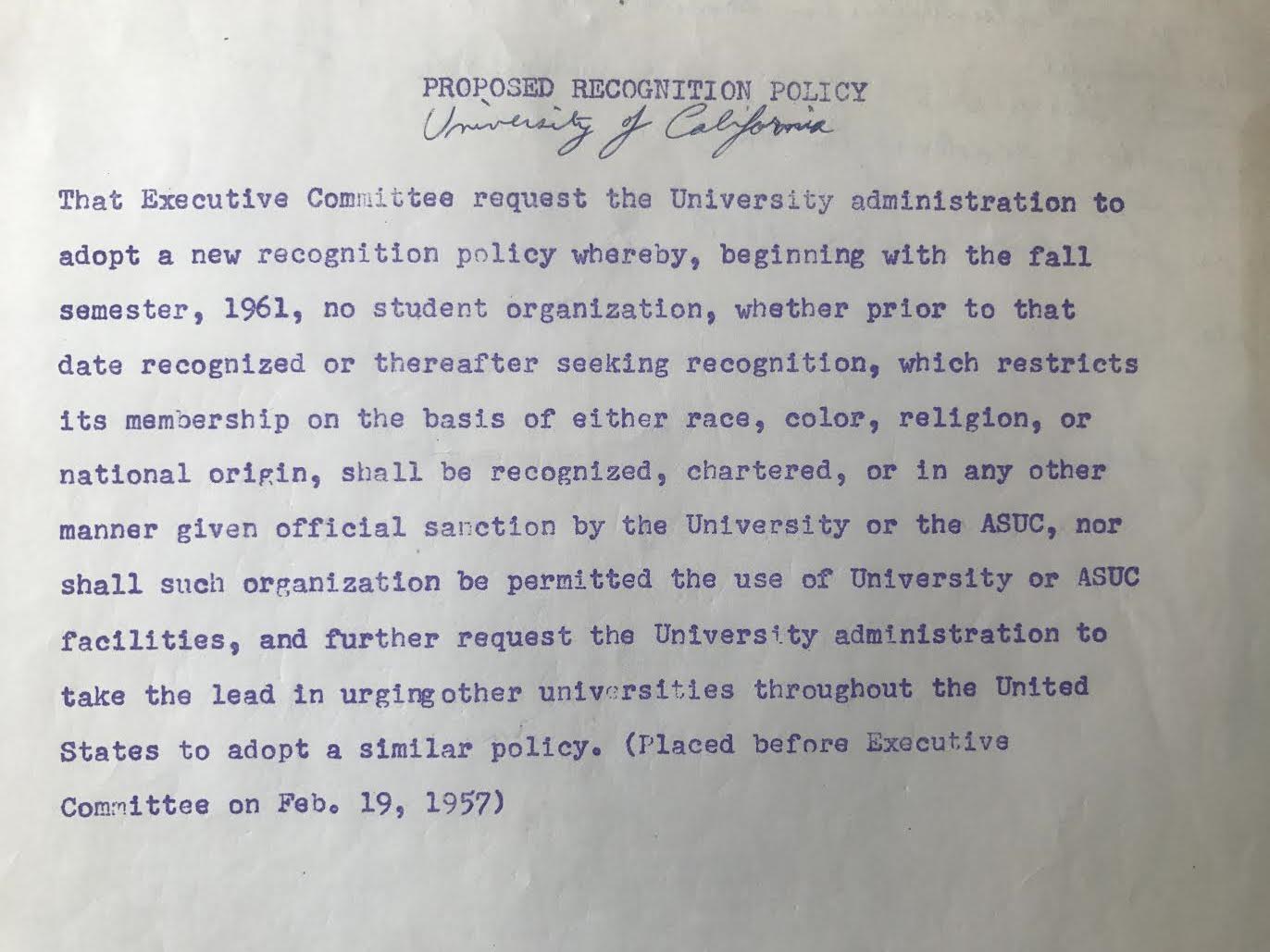

On February 19, 1957, Shaffer submitted what came to be known as the “Shaffer Bill” to the Executive Committee. It requested a University policy prohibiting racial discrimination. A mimeographed copy of the “Shaffer Bill” is the lead graphic in this post.

Shaffer did research, corresponding with peers at Dartmouth and Wayne State University which had passed anti-discrimination policies. The Daily Californian carried editorials and letters about the”Shaffer Bill” The paper eventually endorsed the bill, but the opposition of the fraternities and sororities was strong. In the spring of 1957, the Executive Committee voted to table Shaffer’s proposal.

On April 22, 1957, Chancellor Clark Kerr issued a statement that the University would not withdraw recognition from fraternities that discriminated because “such withdrawal could work a great hardship on them.” Not good!

In Sacramento, Assemblyman Elliott obtained an opinion dated January 2, 1959, from Attorney General Pat Brown stating that racial discrimination by fraternities represented an unconstitutional denial of equal protection under the 14th Amendment. Elliott sent a copy of the Attorney General opinion to Shaffer.

Kerr took that opinion to the Regents, and urged them to adopt a non-discrimination policy. On July 17, 1959, the Regents voted to prohibit racial discrimination in fraternities and sororities. The Regents’ policy was phrased softly and the compliance period was generous, but it still angered the fraternities and sororities. The issue did not go away, and de facto racial discrimination continued well into the 1960s.

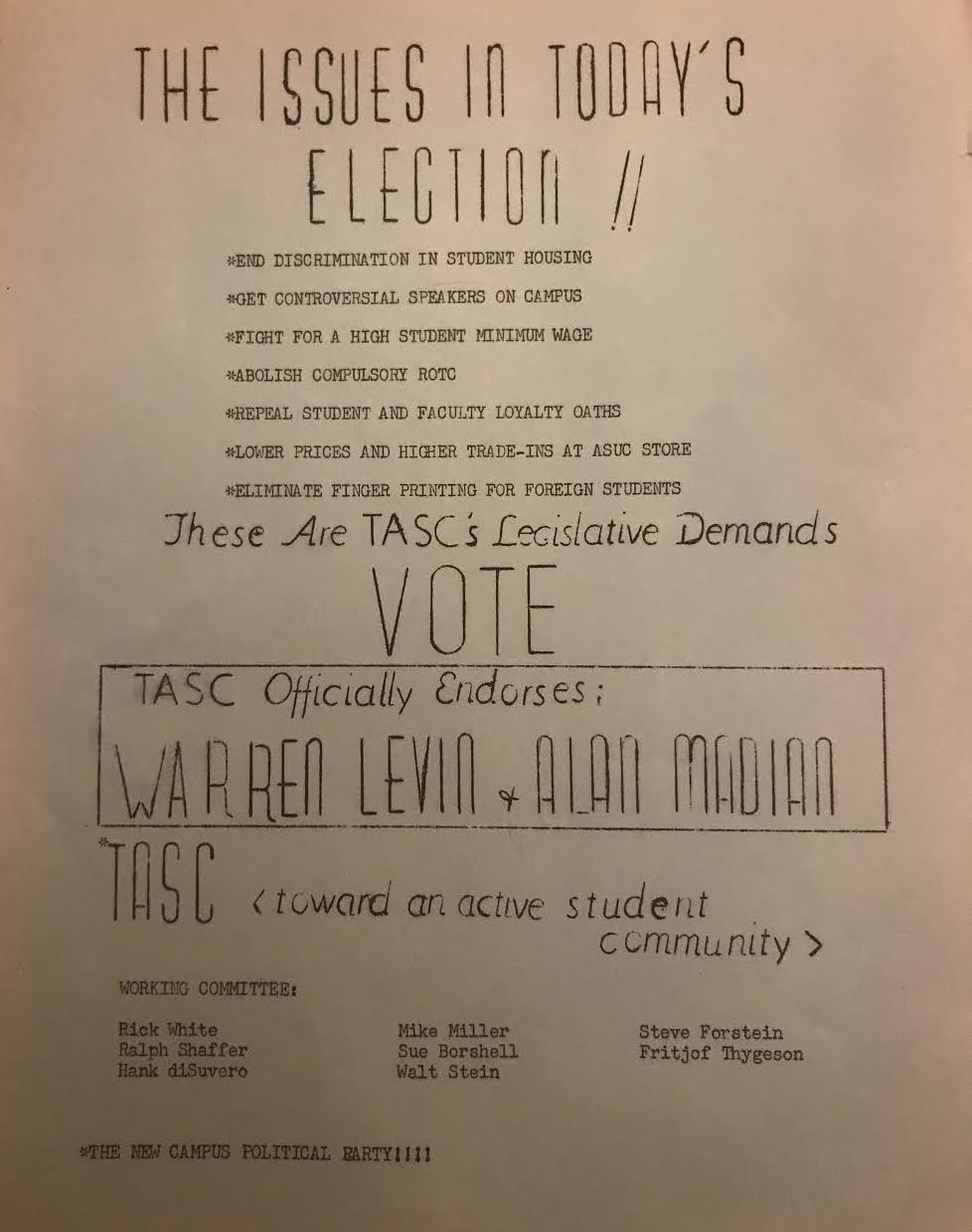

Meanwhile, Shaffer moved forward. He, Fritjof Thygeson, and Rick White organized a campus political party called Toward An Active Student Community (TASC) to run candidates in the student government election on the basis of political principle rather than personal popularity, a radical idea. TASC adopted the British Labour Party system in which any TASC candidate for office was required to submit a signed letter of resignation which the party could file at any time that it felt that the candidate had deviated from party positions. TASC’s candidates ran on a liberal platform.

The issues identified in the leaflet above were all university-related.

They won no undergraduate seats on the council.

In 1958, Mike Miller, an undergraduate representative on the ASUC Senate, resigned and organized a slate of candidates to run on a platform supporting racial equality, free speech on campus, and voluntary ROTC. Miller was trained in the Saul Alinsky model of community organizing.

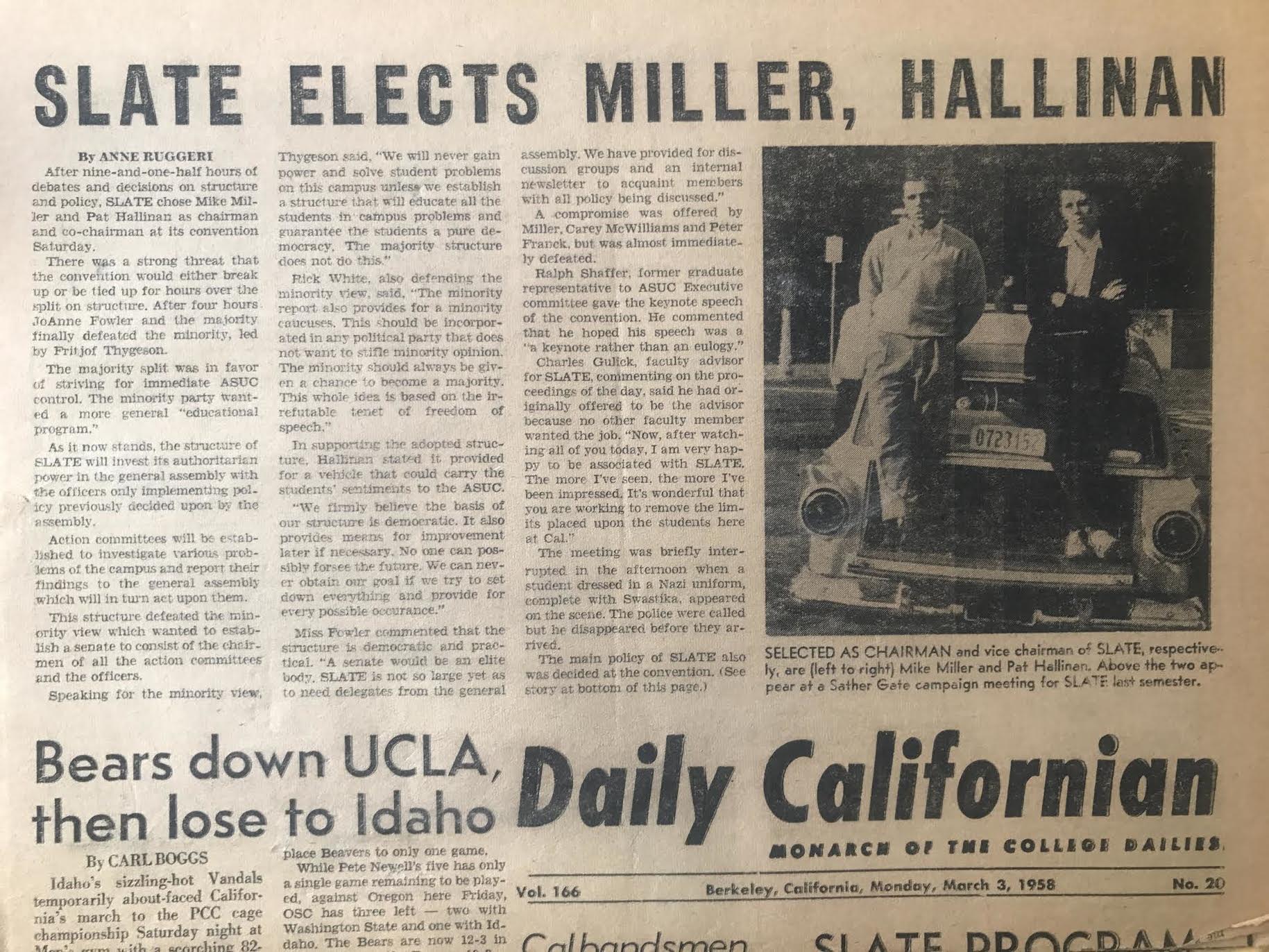

They did well and took things a step farther, establishing SLATE as a campus political party in February 1958. SLATE was not an acronym, but simply stood for a slate of candidates who ran on a common platform. The university administration approved SLATE as a student organization but not as a political party.

By now, Shaffer was living in Sacramento and teaching high school as he prepared for his written doctoral exams.

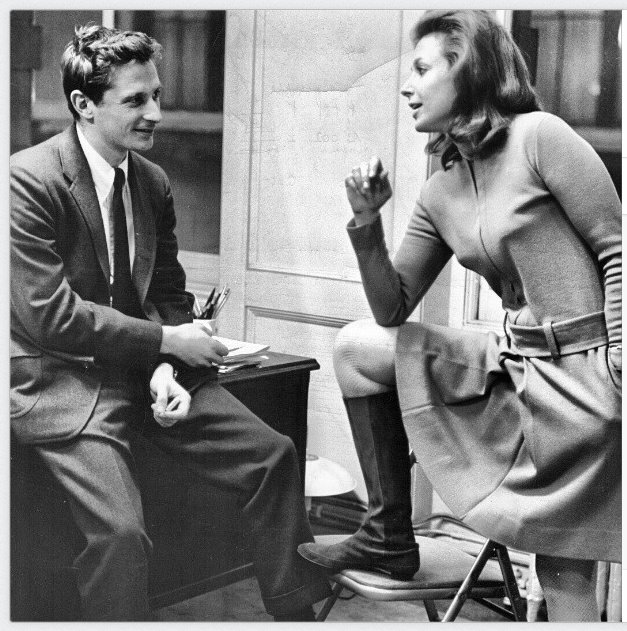

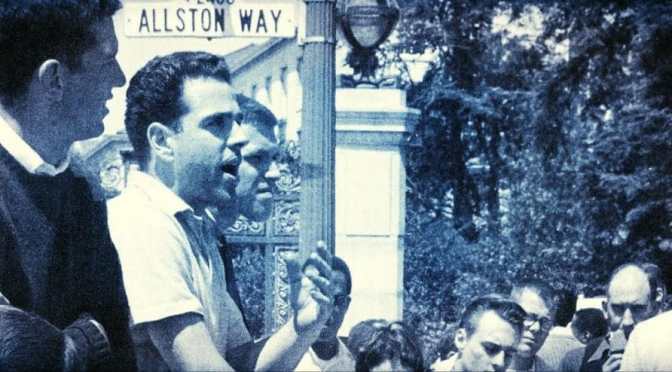

His only connection with SLATE was to give the keynote address at its founding convention. The photo from the Daily Californian is very grainy, I know, but there we have Ralph Shaffer at the founding convention of SLATE.

The agenda for the convention:

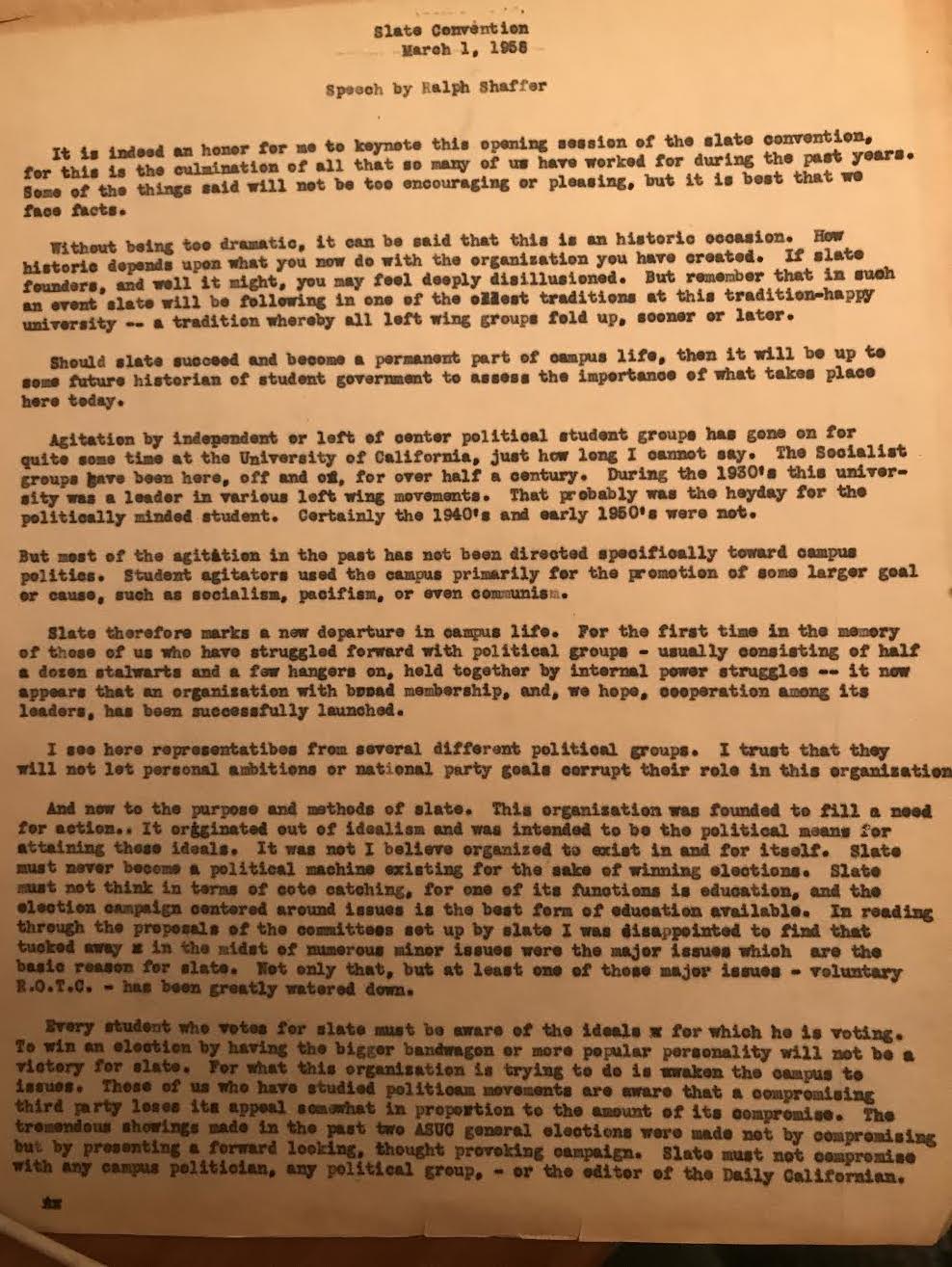

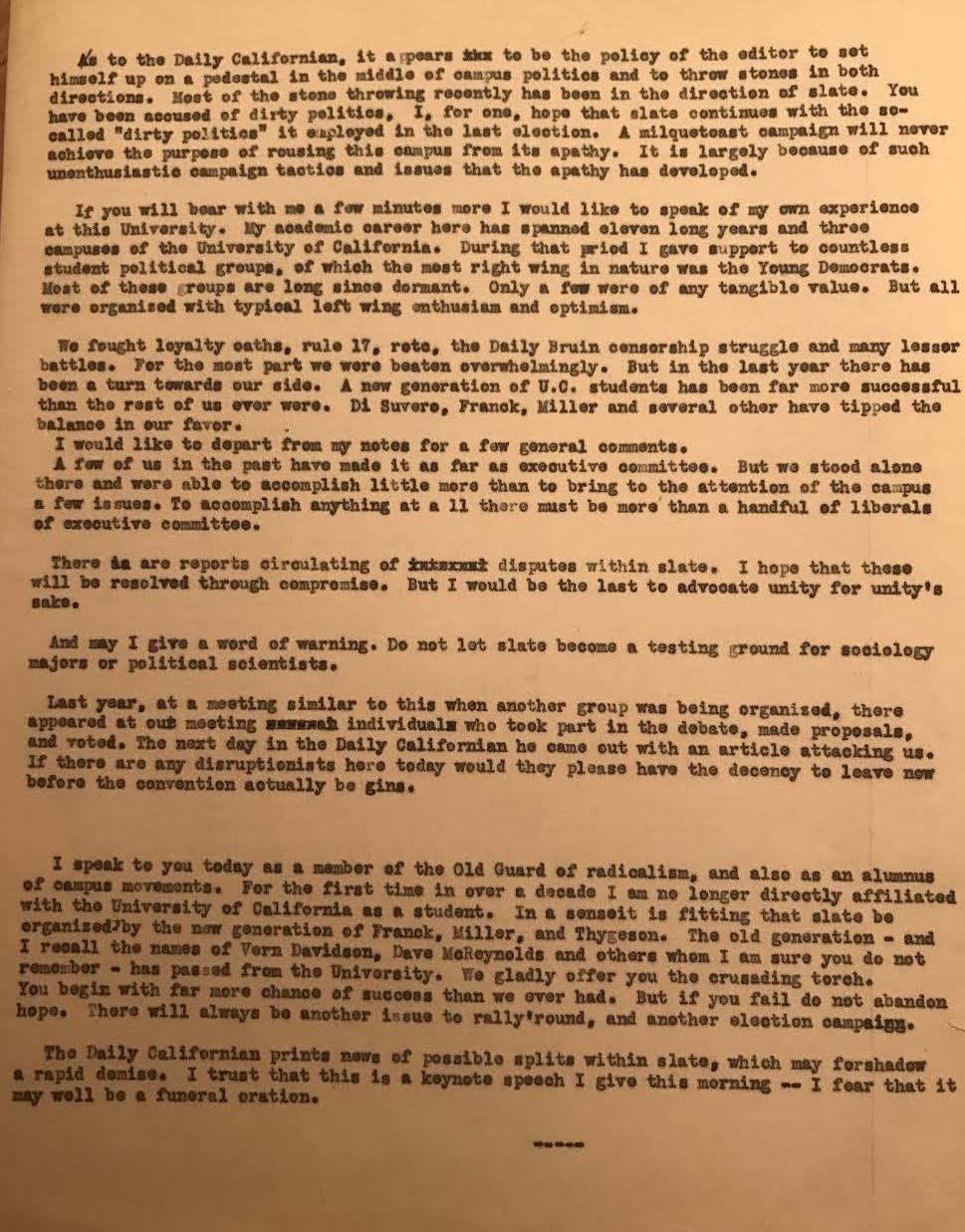

Shaffer’s keynote speech:

The results of the convention:

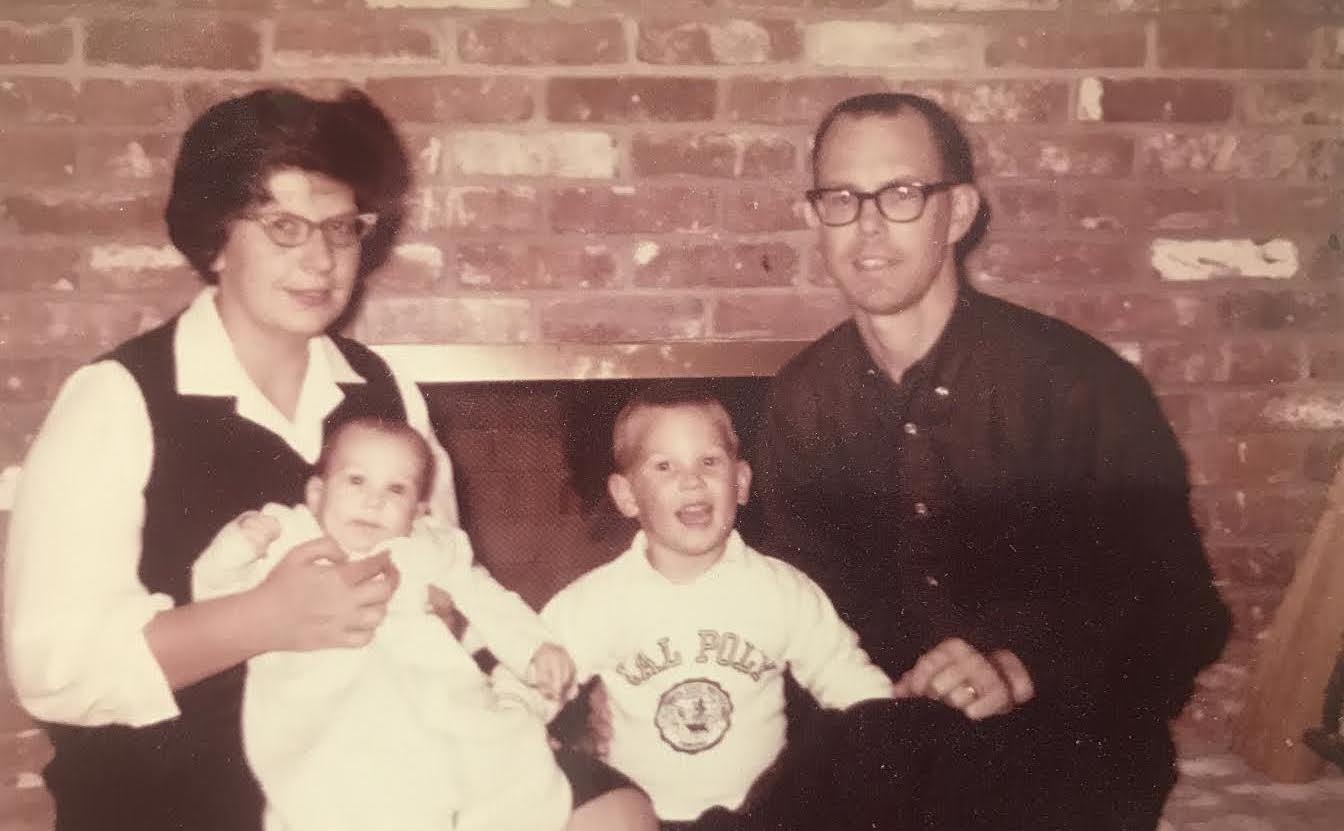

Also in 1958, Shaffer married Diane Usab. whom he had met in 1956 at a social event at the Wesley Foundation, a not-especially-dogmatic Methodist organization on Bancroft. She came to Cal from Detroit via Long Beach City College in the hope of getting her degree in mathematics and teaching. She could not complete her degree for financial reasons caused by Cal’s determination that she had to pay out-of-state tuition. Instead, Shaffer jokes, she got her MRS degree.

Here they celebrate Christmas with his parents in 1960. He had just passed his doctoral exams and was now focusing on his dissertation.

In 1962 they were living in Walnut Creek. Scott had been born. Shaffer’s dissertation on Marxism in California had been approved and he would soon take a job teaching history at Cal Poly Pomona.

By 1964 they had moved to Covina and built a house. Shaffer was teaching at Cal Poly Pomona and Ken had been born.

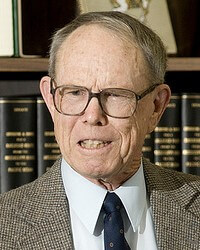

Shaffer has sustained his belief in socialism all these years.

He watched Operation Abolition, an anti-communist propaganda film produced by the House Unamerican Activities Committee. He saw the San Francisco police attack Berkeley students protesting the 1960 HUAC hearings in San Francisco. He considers this as the first real physical effort, one that transcended ideas and debate. When the Free Speech Movement started, Shaffer watched with wonder and admiration. He was not, and is not, sure that he would risked his teaching assistant job by getting arrested. There was no threat of arrest in 1956 or 1957. He doubts that he would have gone that far.

For more than 40 years, Shaffer has been a prolific newspaper op-ed writer. He has filing cabinets filled with his left-leaning pieces, a few of which may be found here.

Shaffer is 87. Diane died 11 years ago. Shaffer’s vision is restricted, but his mind is not. He is fully engaged politically. He keeps in touch with friends and fellow travelers from all those years ago. He has attended a SLATE reunion and keeps up. He thinks. He analyzes. During the 2016 election he urged civility in political debate: “Why can’t the citizens of a nation whose First Amendment is a protection of free speech honor the right of their opponents to practice that right without harassment?”

He downplays his importance in the development of political culture at Berkeley. I don’t. I admire the courage that it took to step from the shadows and speak. He may have been a small cause, but he was a small cause without whom there would have been no large effect. Small changes in the initial conditions of certain physical systems have inherently unpredictable results. So it is with politics and culture and life. So it was with Ralph Shaffer.

I showed the post to my friend. He curled up in his Eero Aarnio Ball Chair in his quarters to read the post.

Looking at him, you wouldn’t guess that he prefers the culture of the fifties to the culture of the sixties. He is an avid reader. He has a collection of books about the fifties. He wants to write a book about the fifties, based on Lenny Bruce’s brilliant observation that far out depends on where you’re standing. His premise is that the early, modest movement from orthodoxy and the conventional is as significant (and for him at least, more interesting) than the major movement that follows.

Which adds up to this tale of Ralph Shaffer in 1957 being of great interest to him, right in his wheelhouse.

I hope that this tale speaks to others, to those who care about our Dear Old Berkeley, to those to whom the destruction of The Village is unthinkable, those to whom building on People’s Park is unthinkable, to those to whom the pro-development fervor is just a little unsettling.

What does he think of what I put together here?

Thank you for this. It is fascinating. My parents went to Cal between 1947 and 1955 ( including grad school) and I am looking forward to asking my mom about then. I enjoy reading your blog alot.

PLEASE let me know what they have to say.