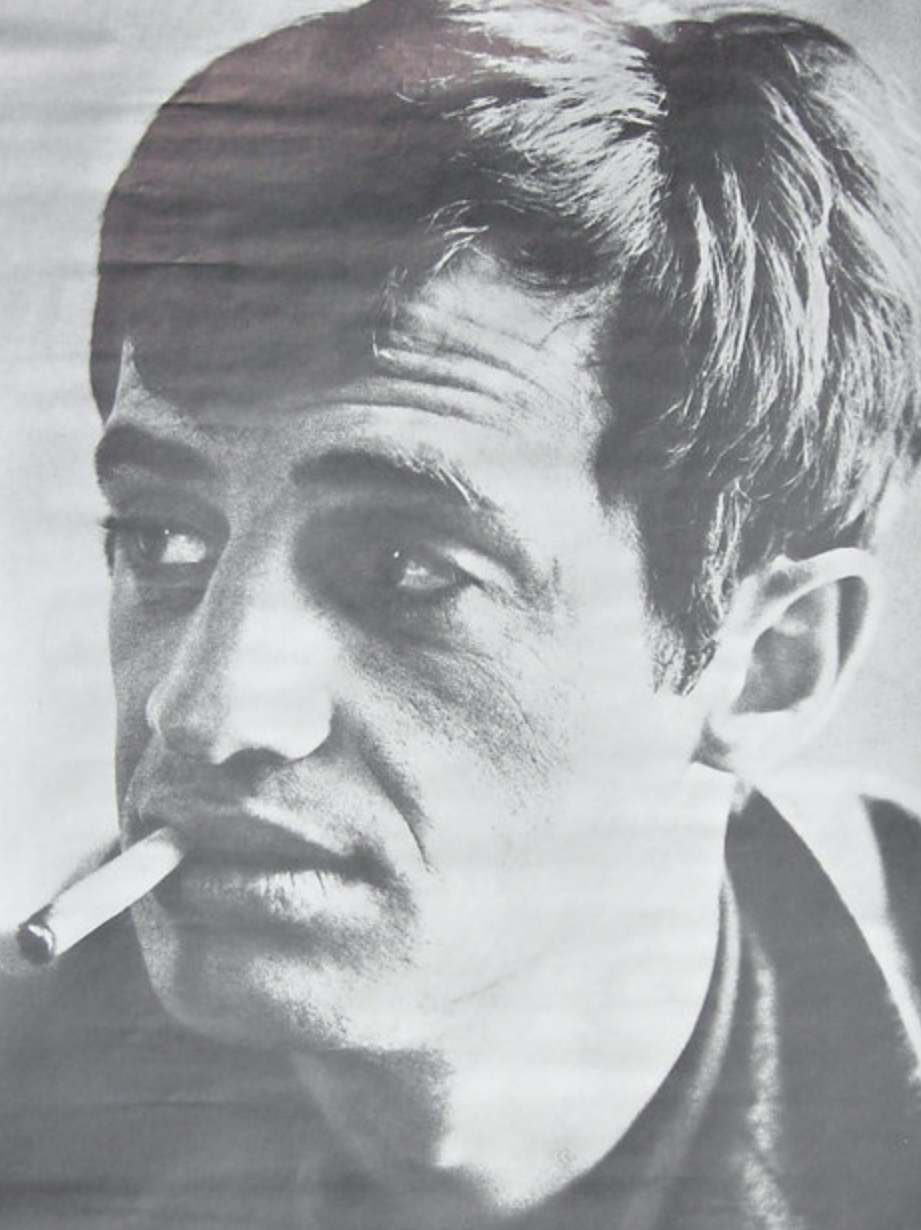

Screen-grab from The Graduate, in which Dustin Hoffman looks out the window of the now closed Caffe Med across the street to Moe’s Books and Print Mint. Can you hear Simon and Garfunkel’s “Scarborough Fair/Canticle?” Elaine will emerge from Moe’s, don’t worry.

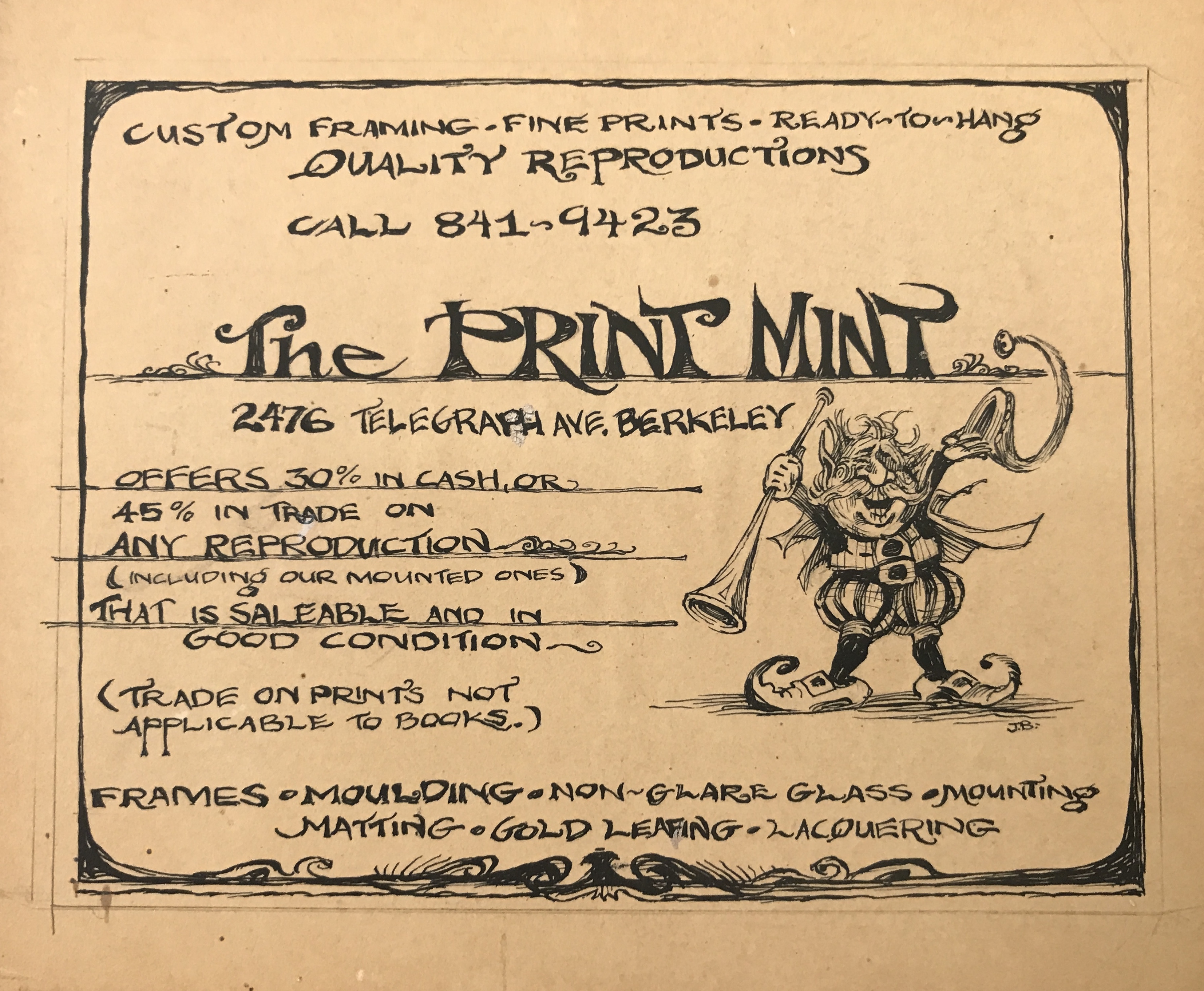

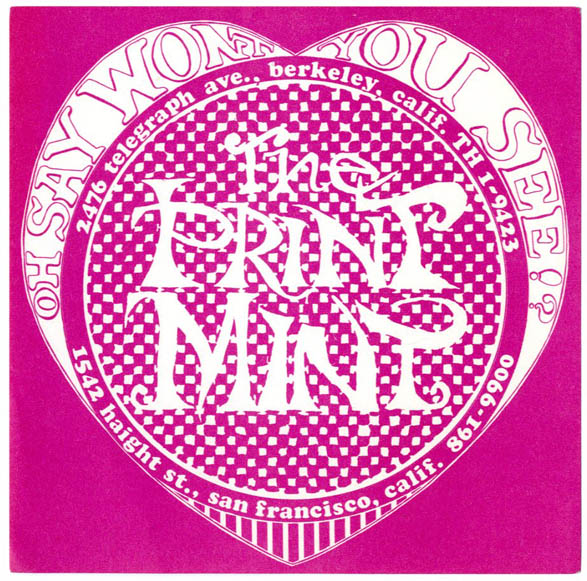

When Don and Alice Schenker opened the Print Mint inside Moe’s Books on Telegraph in 1965, they weren’t the best at what they were doing. They were the only ones doing what they were doing. Along with espresso or Galoises or out-of-town newspapers or used books and records or croissants, you could now buy posters and art prints on Telegraph. Odd as it may sound now, it was a revolutionary thing.

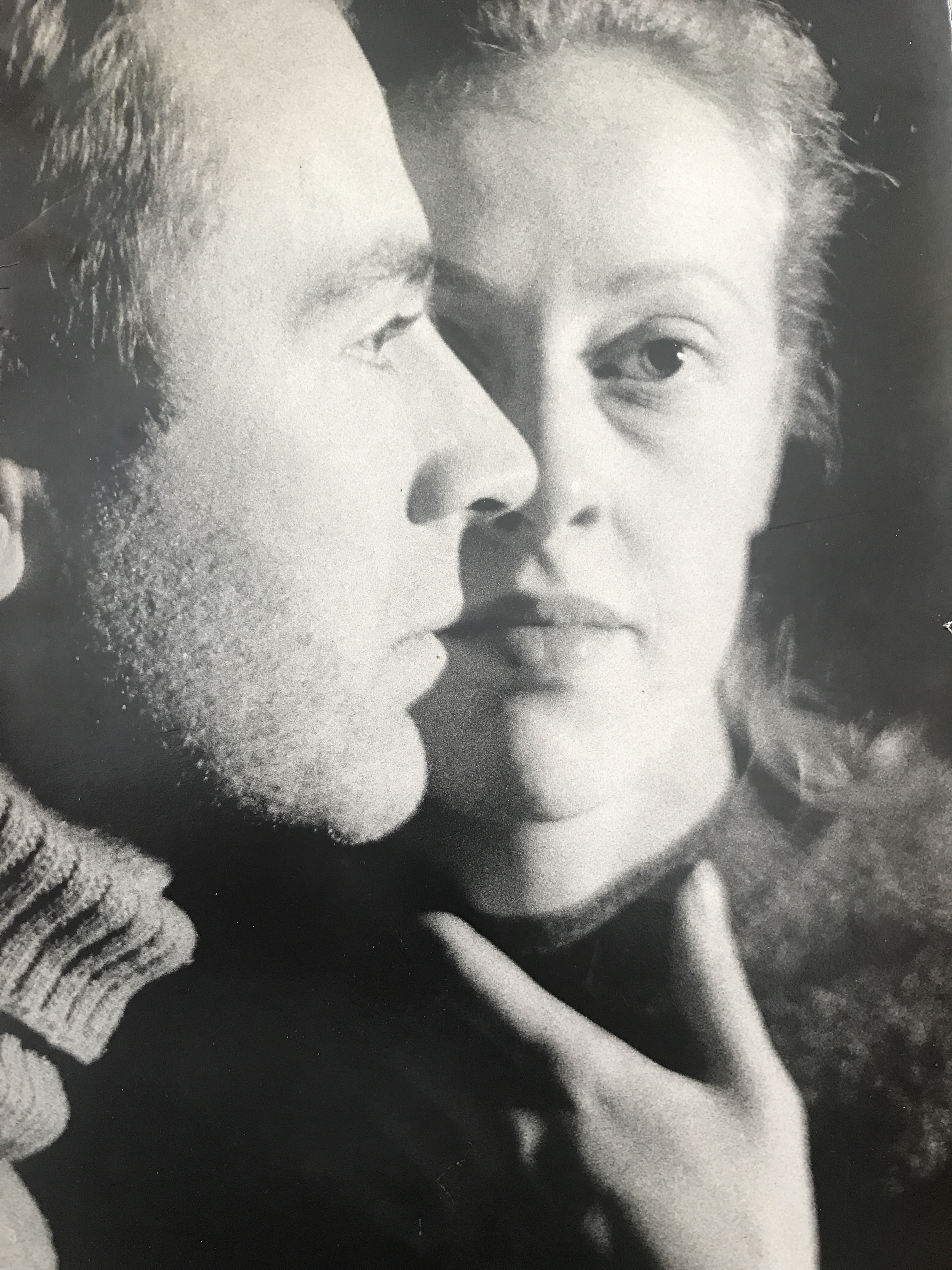

Don and Alice met in New York in the mid 1950s. He was from New York. She came to New York from Wisconsin via Antioch College.

They were loosely part of the evolving Beat/Bohemian scene – day jobs but taking classes at the Art Students League and eventually having an enameling studio in Greenwich Village. Don wrote poetry.

They married.

In 1957 they set off to Mexico in a 1941 Buick that they bought for $100. They had read an account of a camping trip made with a donkey caravan by a couple through the state of Michoacan. Alice: “What snagged us was their description of Zirahuen, it’s beautiful lake setting.”

Alice wrote a six-page account of their trip years ago, which I have excerpted below. All six pages may be seen here.

As they drove through the South, Alice writes: “Each night we looked for an out of the way place to sleep in our car without being bothered. Off the usual path, we got glimpses of the segregated South that were the landscapes of novels. Imagination easily conjured up the lurking evil of this segregated system with violence on the edges.”

They stopped in New Orleans and were swept up by “the architecture with all its iron work, the courtyards and gardens full of fragrant plants and vines, the French market serving that wonderful chicory laden coffee, the wharfs and levees with all their activity, the Bourbon St. Jazz scene.”

Then through Texas, into Mexico. In Mexico City, they met “young Cubans involved with the revolutionary movement brewing in the mountains of that country.” There was some animosity towards the Schenkers until the hotel proprietor showed the Cubans that Don was reading Lorca. “There was an immediate change in the mood to one of festivity.”

Their destination was Zirahuen, Michoacan. Alice describes their time there – “Every day was quite a day. Not our vision of undistracted time to pursue the arts.” A social gaffe (giving a young man $5 which he spent to get drunk and raise hell) led to the decision to leave Zirahuen.

They went to Patzcuaro and stayed at the Hotel Ocampo. Alice writes that by then they were “having some serious doubts about our decision to live in Mexico. We’e done hardly anything so far to drum up future income, being so busy with just ‘living in Mexico.'” They decided to fix the car and leave. “We left after a mere 3 months in Mexico.”

Where to? San Francisco. Passing through Big Sur, they stopped and gazed at Henry Miller’s mailbox but didn’t attempt a visit.

As they neared San Francisco, they took a motel room just south of the city because Don wanted Alice to see the city for the first time in the daylight.

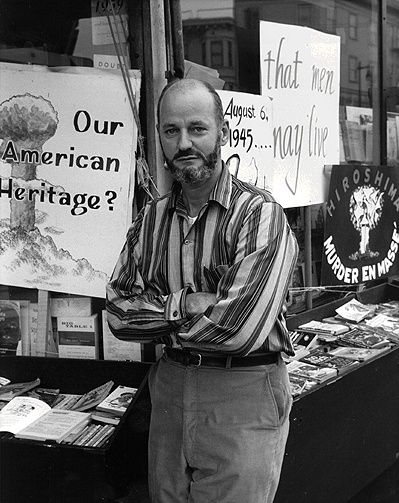

The next day – San Francisco. Don was anxious to see City Lights, the epicenter of the San Francisco/Beat poetry movement. Alice: “Ginsberg’s book had caused a lot of excitement and we were aware that he and others were the center of a ‘poetry scene’ going on in San Francisco.”

They went to the store and met Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

He invited them to a party with Kenneth Rexroth, a poet who was a central figure in the San Francisco Renaissance poetry movement. Rexroth didn’t consider himself a Beat poet, but Time magazine did, crowning him “Father of the Beats.” Not a bad first night in San Francisco for the Schenkers!

That summer they ran into Jack Kerouac, who if I have the chronology right was briefly living in Berkeley with his mother. They took a very drunk Jack back to their apartment one night from a party at Baker Beach, pulled down the Murphy bed, and slept as a chaste threesome, Don in the middle.

In March 1958 they returned to New York for six months, and then came back to San Francisco where they lived for the next seven years. Don wrote poetry, publishing one volume with David Meltzer.

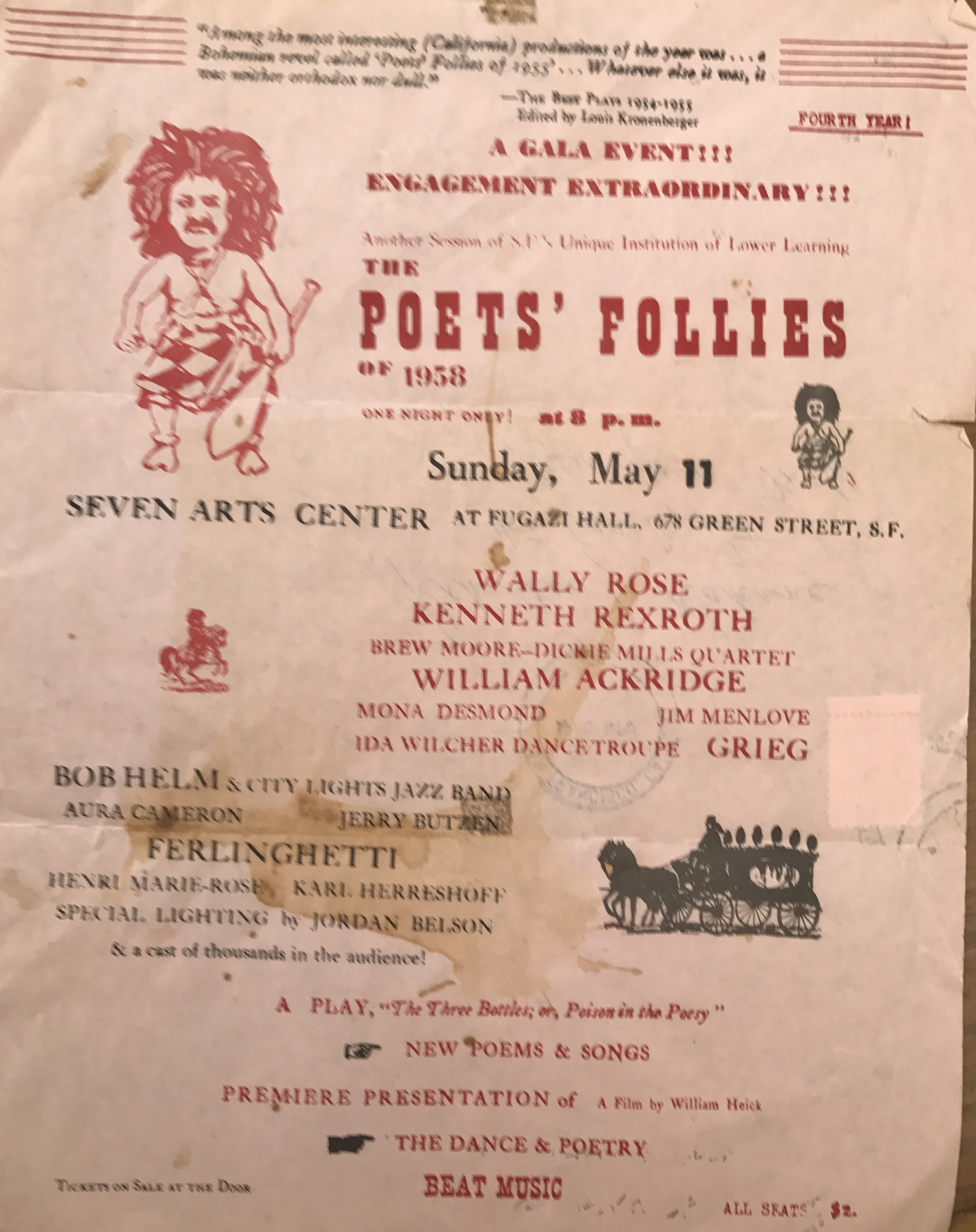

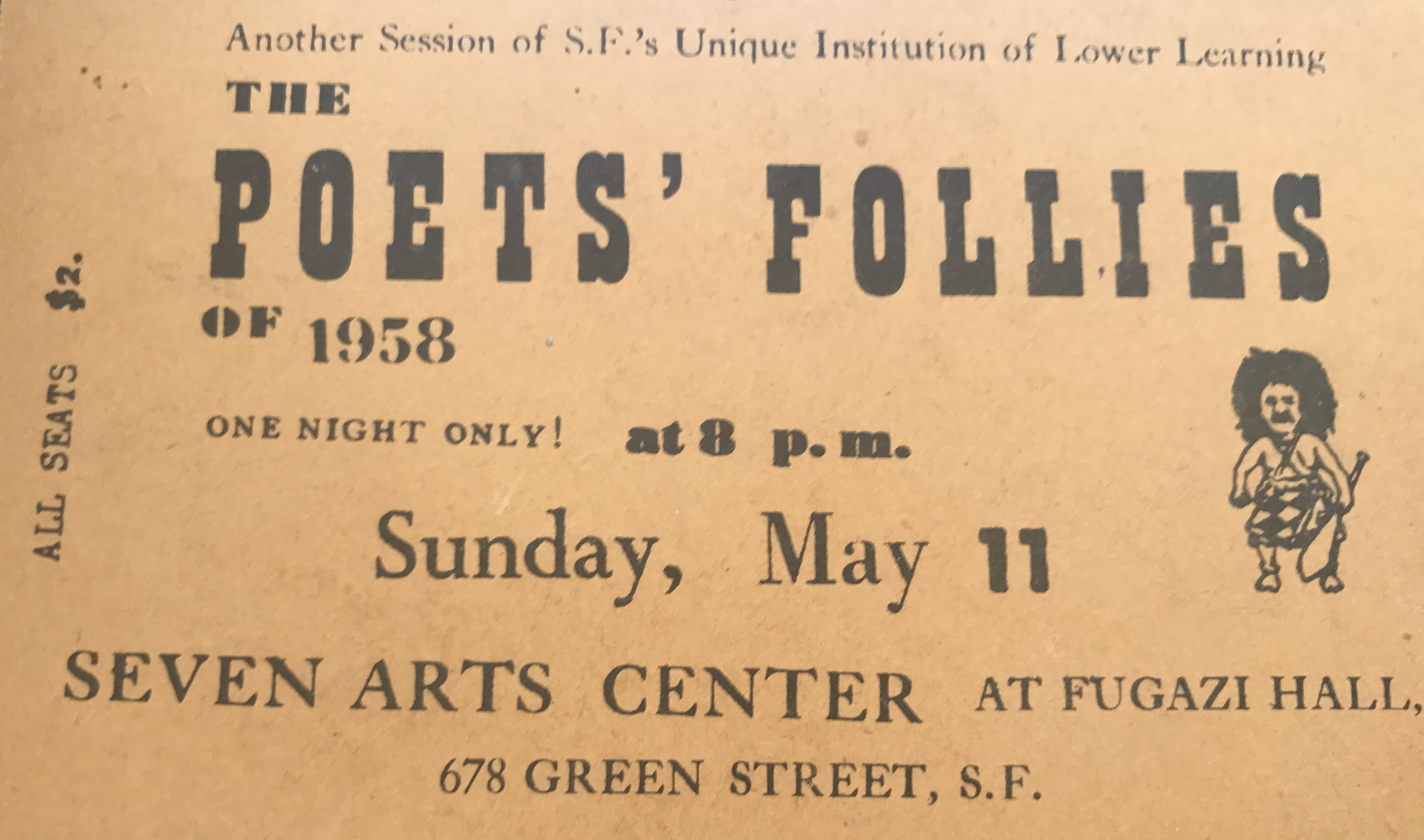

While in New York, the Schenkers had gotten a flyer about the Poets Follies.

In 1955, housewife Phyllis Diller appeared with Lawrence Ferlinghetti and poet Weldon Kees in “The Poets’ Follies of 1955,” a musical revue.

Diller parlayed herself into a booking at the Purple Onion nightclub in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood on March 7, 1955, where she was introduced as the “dingy dilly delirious doll from Donner Pass” – appeared for a year and then moved on to the Los Angeles Purple Onion for four months. From there it was on to the Blue Angel and the Bon Soir in New York, Mister Kelly’s in Chicago, the Crescendo in Los Angeles, the Jack Paar Show, and fame.

Oh what a life it was!

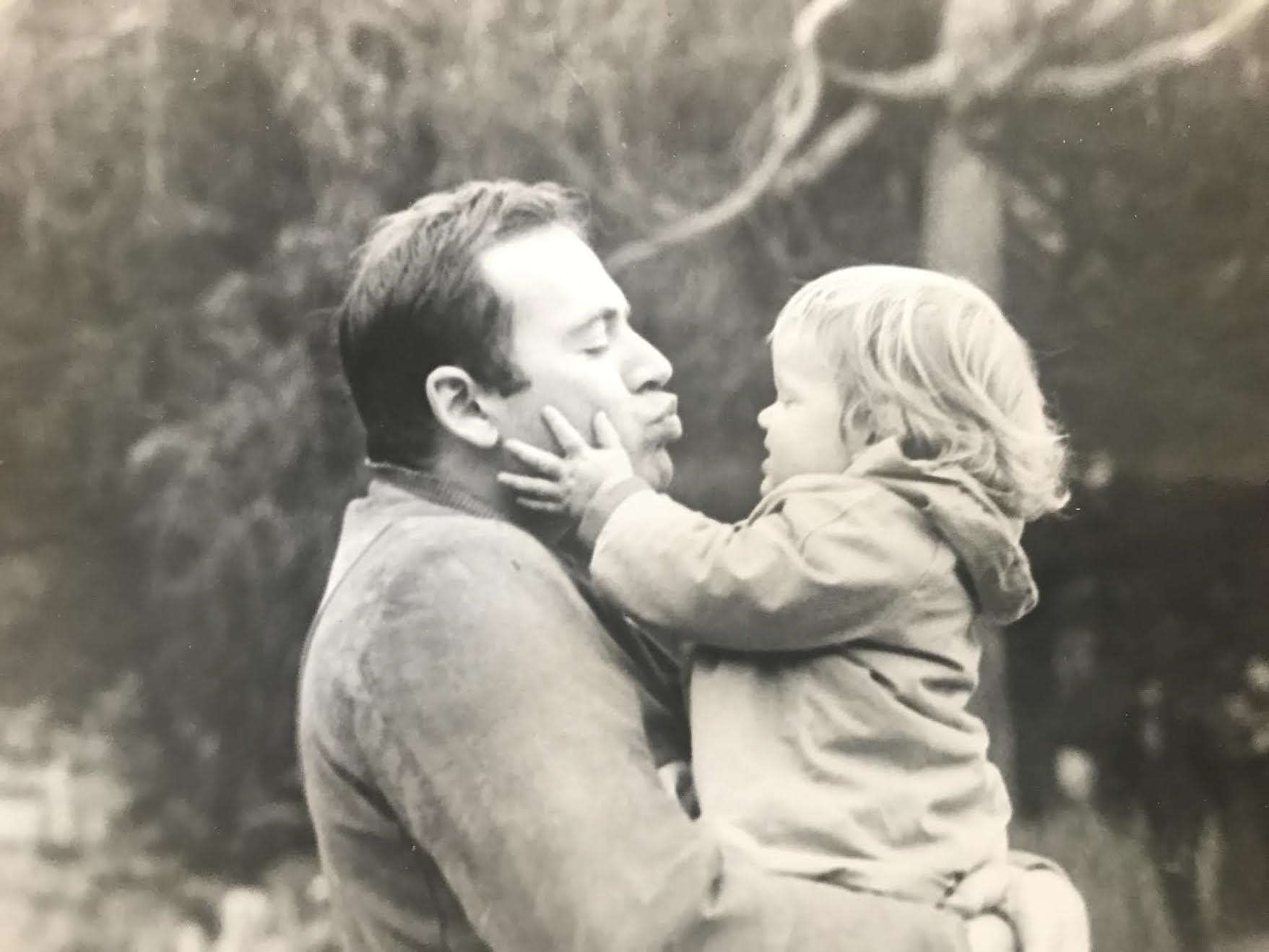

They started a family, and Don worked at Flax Art Supplies, where he perfected a print-mounting technique.

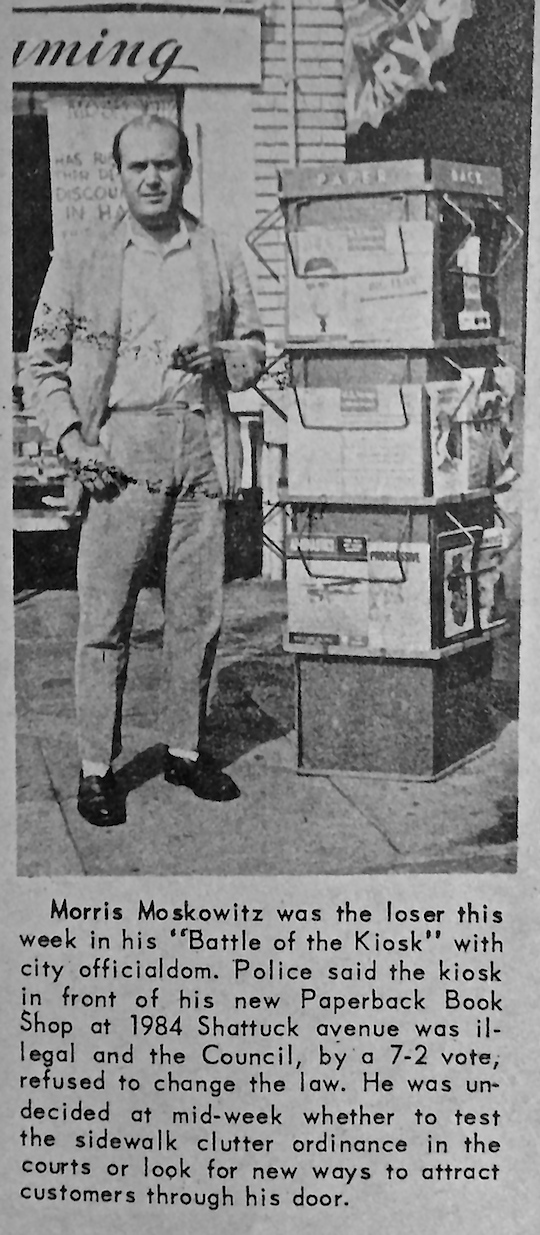

In 1958, Moe Moskowitz arrived in the Bay Area. The Schenkers had known Moe in New York, where he worked for art galleries, studied violin and was a member of the Living Theater acting group. Julian Beck and Judith Malina founded the Living Theatre in 1947 as a transformative art form. Its productions were often multimedia efforts and the so-called “fourth wall” between the audience and actors was often ignored. The work of the Living Theater was ground-breaking and challenged the status quo of the theater.

So – Moe showed up. He opened his first bookstore at 1986 Shattuck just north of University, currently the home of the Turkish Kitchen. Next stop was the northeast corner of Telegraph and Dwight (until a year ago the home of Shakespeare) and a partnership to run Rambam (in honor of Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, commonly known as Maimonides, and also referred to by the acronym Rambam), a used bookstore.

In 1965, Moe dissolved his partnership at Rambam and moved across Telegraph to what had been Cody’s – who had moved to the new building at Haste.

Don and Alice moved into Moe’s store, framing fine art reproductions. Moving into Moe’s was more than a partnership, it was a friendship as well. They’d run in the same Beat circles in New York. Moe and Don went to the movies together every Monday night for 30 years.

Then came posters.

Alice saw a poster of Jean Paul Belmondo and a lightbulb lit up. She called the distributor and a path appeared – sell posters.

Lincoln Cushing has spent his career making and preserving political posters. He has forgotten more than we’ll ever know about posters. He summed up the importance of the Print Mint:

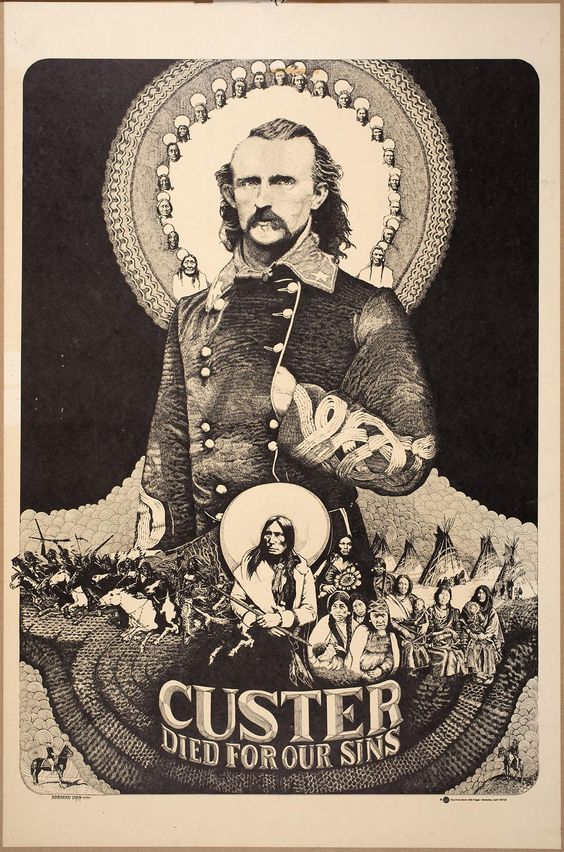

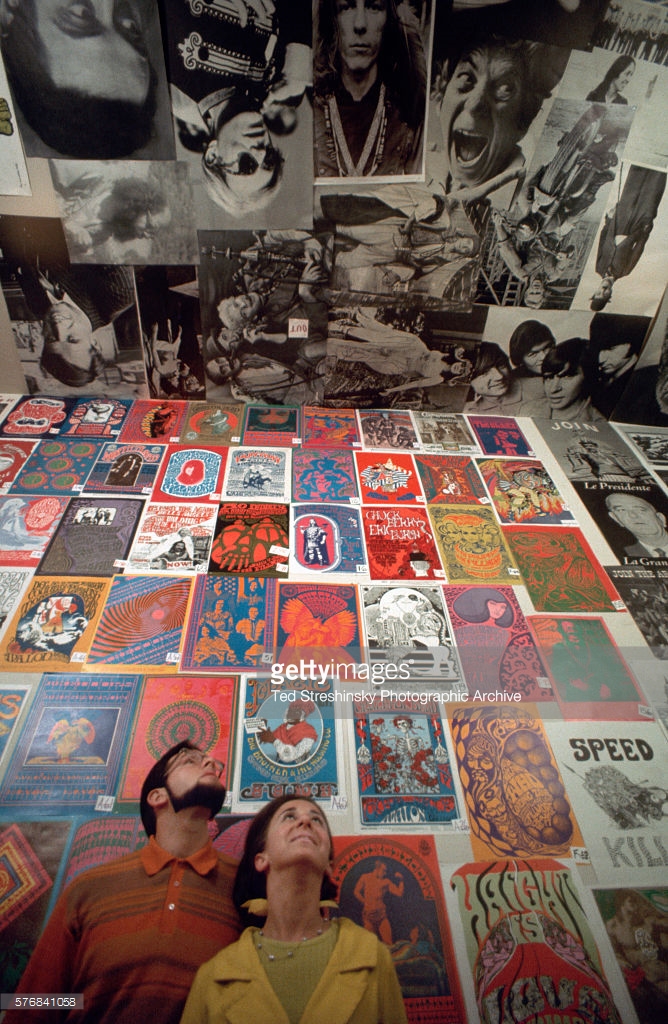

The Print Mint was the first and most influential retail store to disseminate the new poster art of the 1960s. They not only sold posters, they occasionally published them, and between 1967 and 1972 produced dozens of posters on subjects such as impeaching president Lyndon Johnson, supporting the American Indian movement with “Custer Died for our Sins” by Norman Orr, concerts at the Avalon theater, and marijuana culture with a six-foot tall joint. As a political and countercultural poster scholar, I cannot be too strong in emphasizing the importance of the Print Mint in the Bay Area’s – and later, the world’s – 1960s poster renaissance. Between 1945 and 1965, very few “oppositional” posters – public documents critical of the status quo – were issued because of the deep chill of anticommunism. But things broke in 1965, led by the S.F. Bay Area fusion of counterculture and political activism. Two key vectors together were crucial to that breakthrough – the means for making the posters and the means for distributing them. Almost all these posters were either printed by hand in small workshops (usually by screen printing) or were produced at sympathetic offset print shops. New technologies allowed for easier and cheaper ways to create type and to print smaller quantities than ever before. And as people started wanting posters to put on their walls, new distribution channels evolved. Head shops, bookstores, and poster stores provided the physical space to see and buy posters, and artist-run cooperatives made it easy to order them by mail. The Print Mint was ground zero for that deliriously powerful cultural bloom.

Right here – in our dear old Berkeley!

The posters shown in the photo of Alice at the counter above are exactly as I remember early posters – actors and comedians.

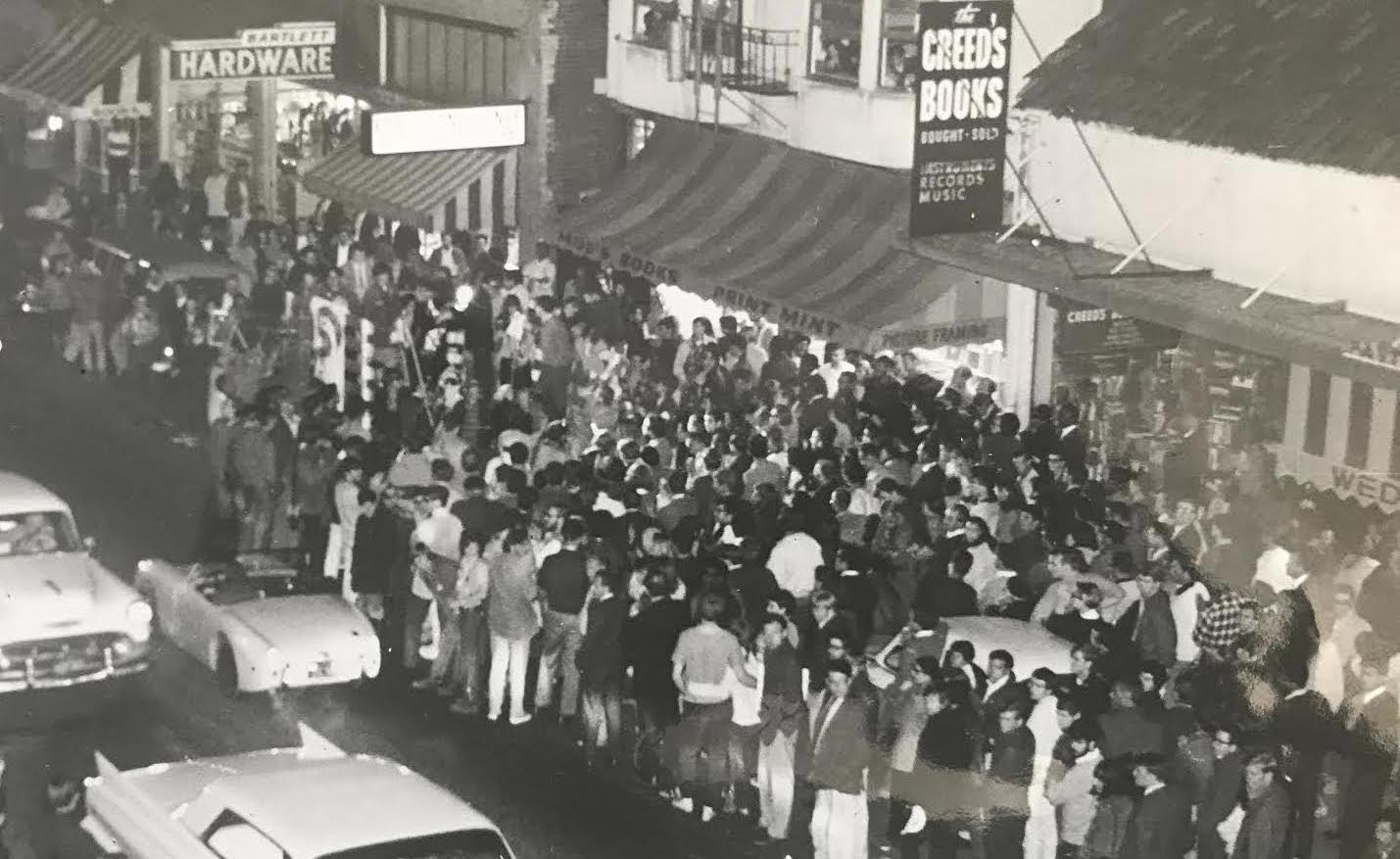

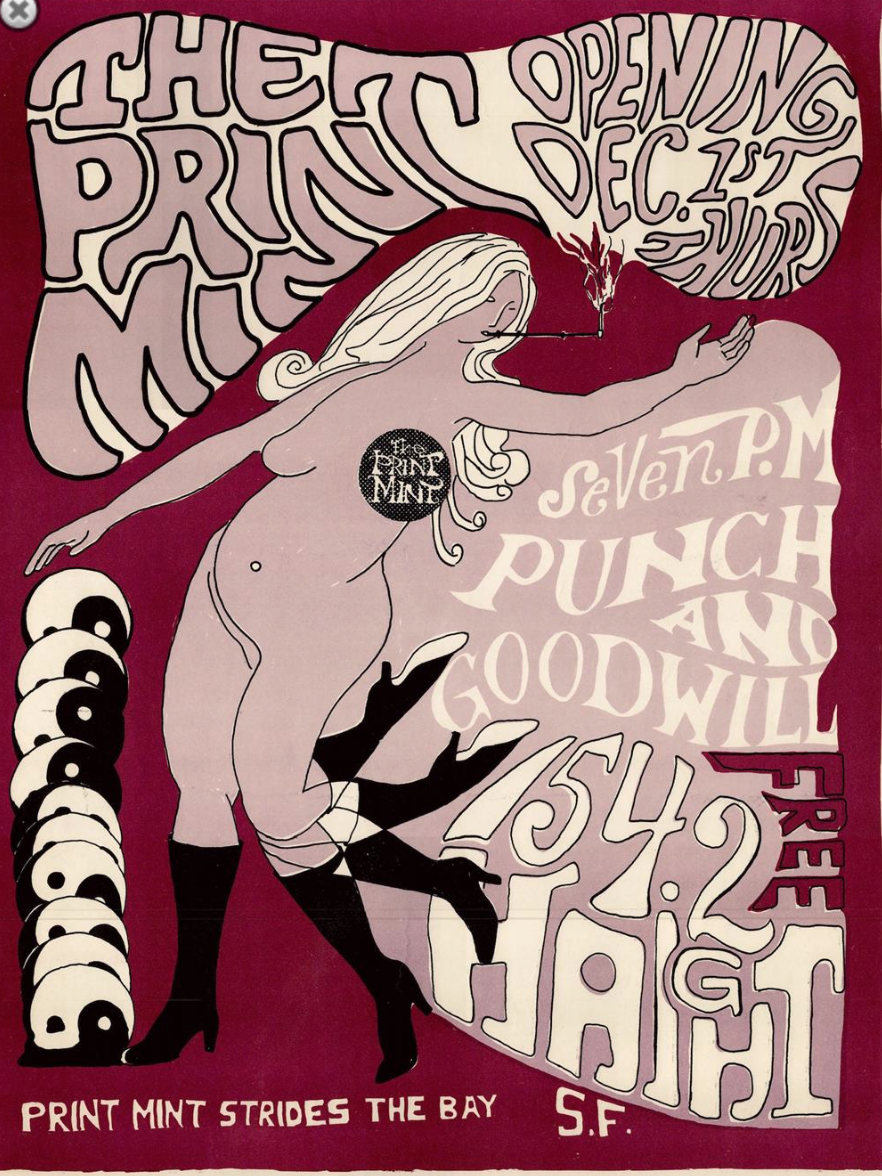

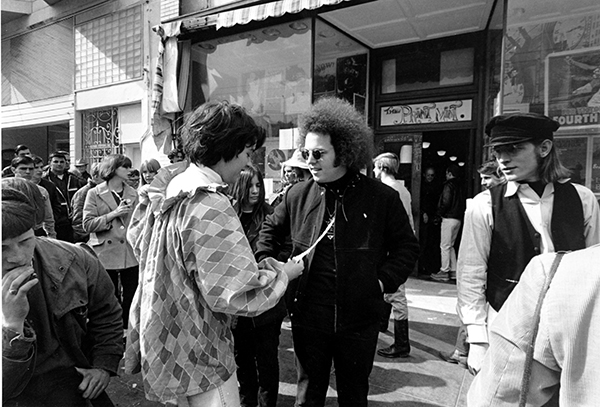

In late 1966, Moe decided to open a store in Haight-Ashbury. The Print Mint followed, and for a year that included the Summer of Love operated at 1542 Haight.

Si Lowinski ran the Haight store, with frequent vists from the Schenkers who kept the Telegraph Avenue store going. .

That summer, mainstream America discovered what the Print Mint had known for a few years – posters were cool.

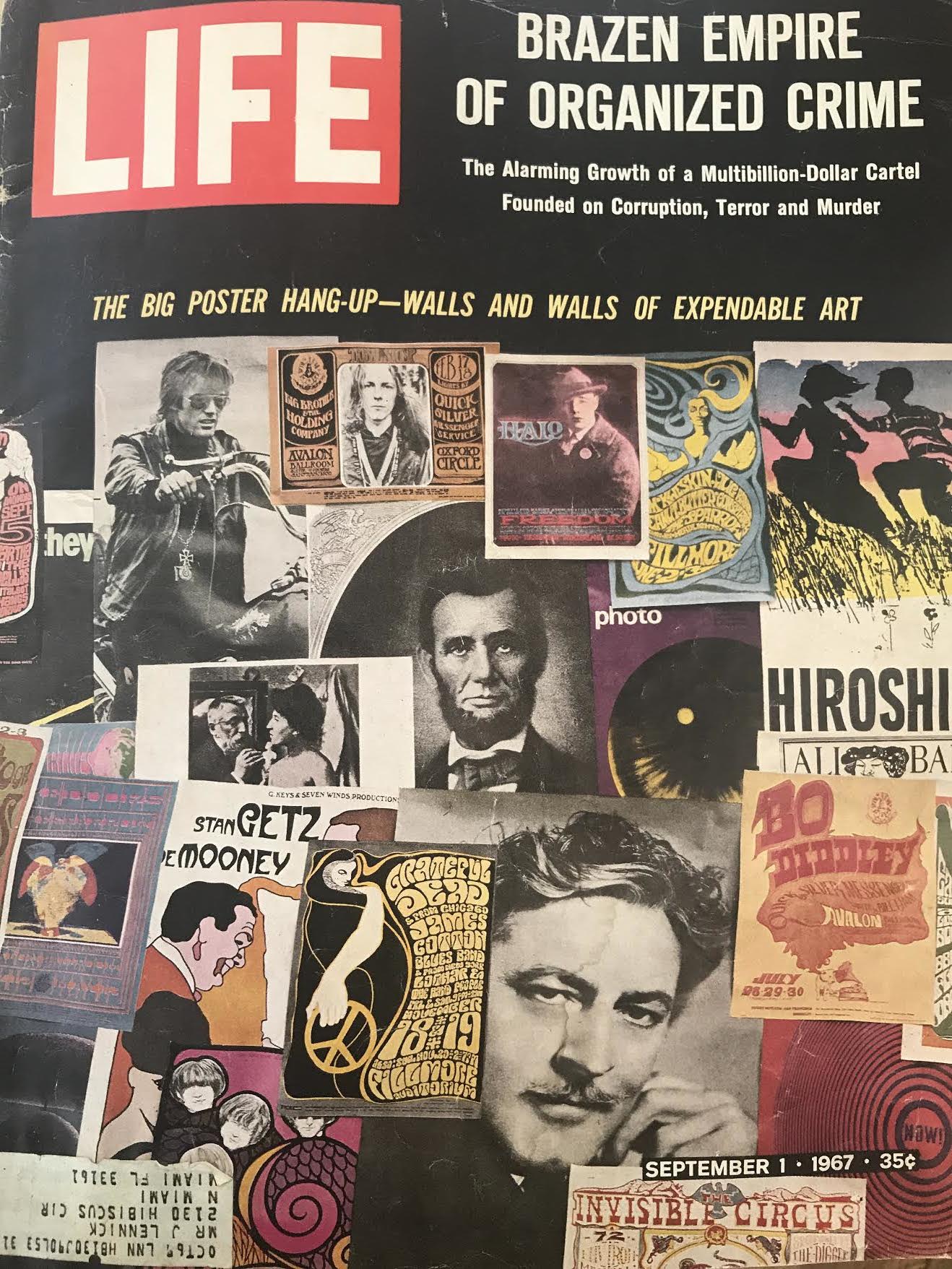

The September 1, 1967 issue of Life magazine shouted POSTERS! to America.

Included in the article was this full-page photo of the Haight Street Print Mint.

Moe never got his Haight store off the ground. He got into a quintessentially Moe battle with the licensing authority and abandoned the plan. As the Haight slipped from the Summer of Love into the Winter of Hard Drugs, the Schenkers closed their Haight Street store and focused on the Telegraph Avenue site.

A couple things happened next, as the Big Changes swept Telegraph and Berkeley and the Bay Area and California and the United States.

Moe’s moved a few stores south when Moe decided to demolish the old Moe’s with the Telegraph Hilton above it and build a new store. The Schenkers at this point set up their own shop next to Moe. When Moe moved into his new building, the Schenkers moved into what had been Moe’s temporary store next to the new building.

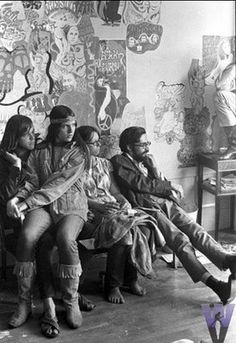

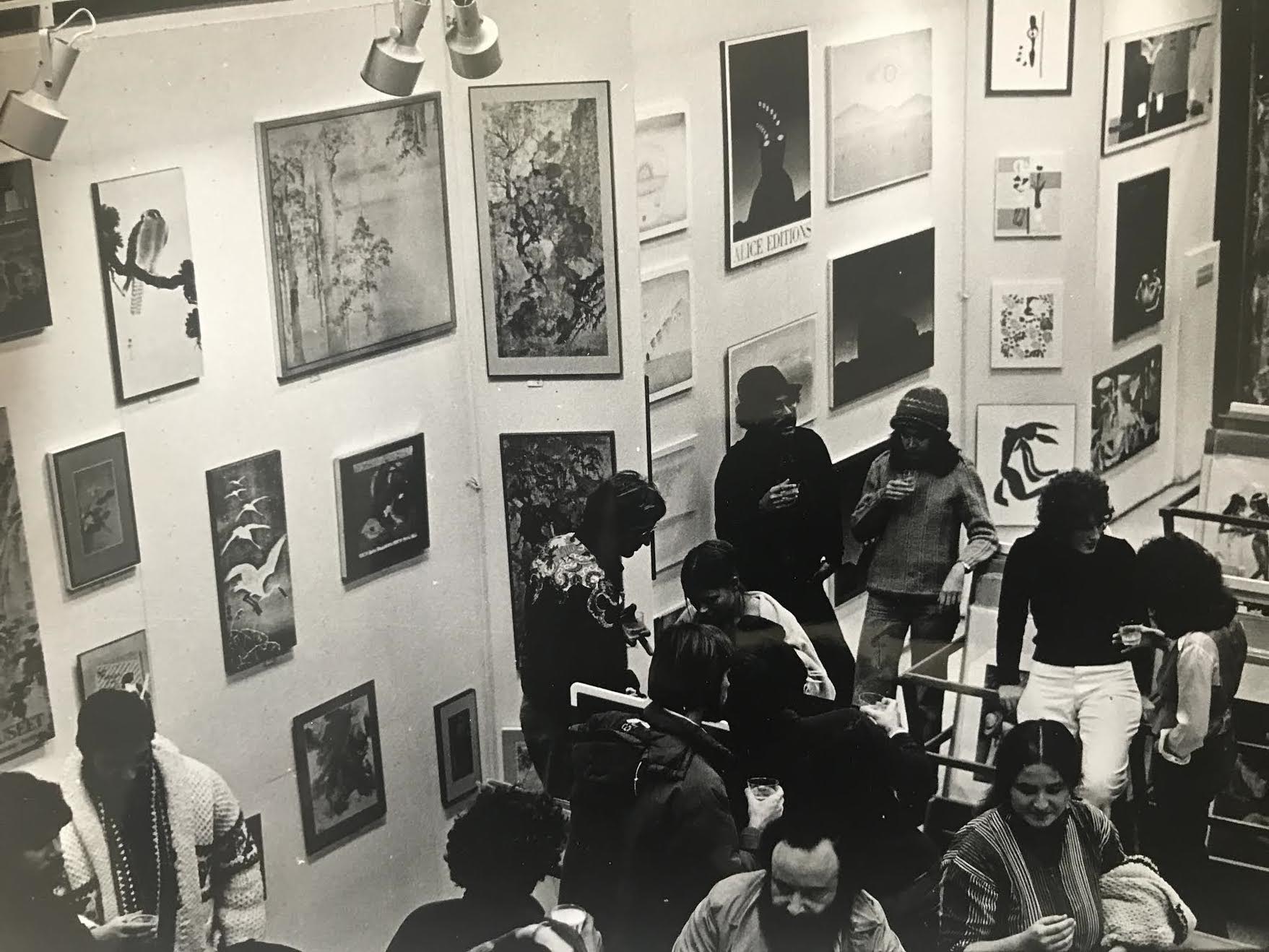

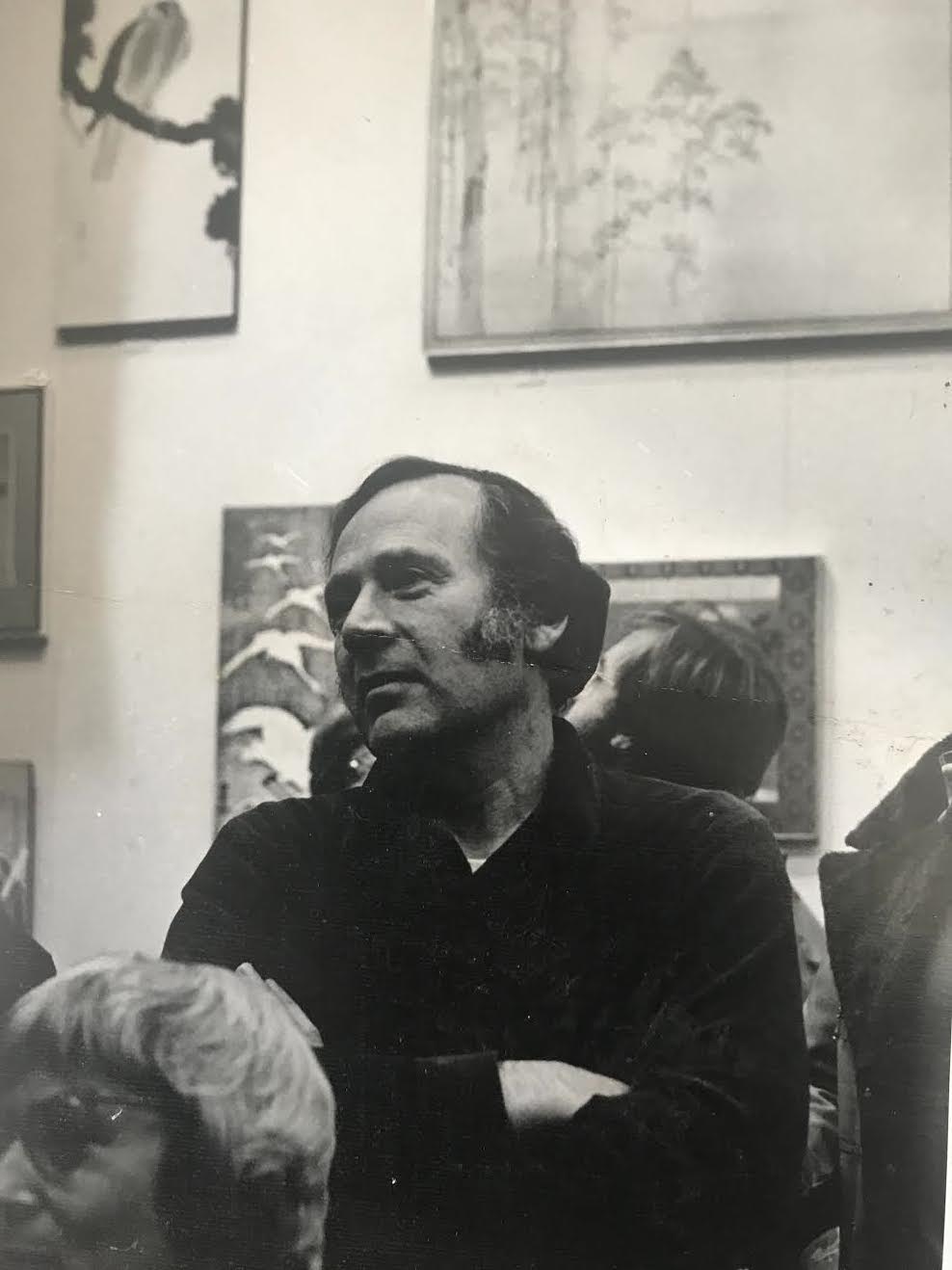

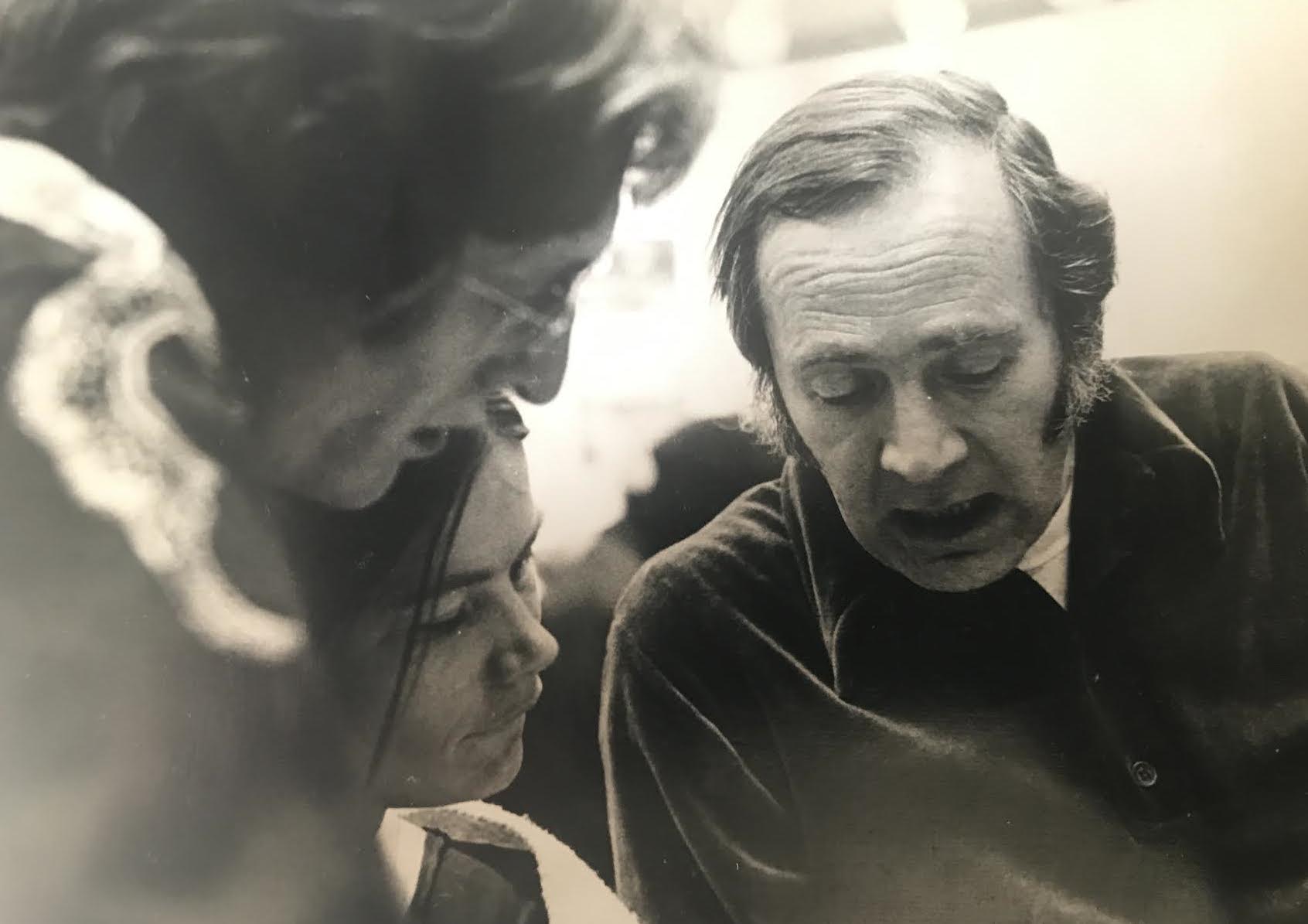

These next photos are from the early days of the new free-standing story.

Don held court at this event.

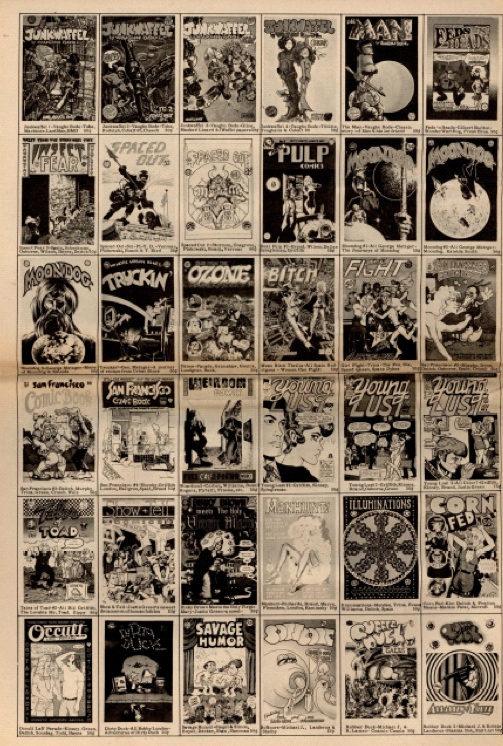

The second big change was the Print Mint’s embrace of the burgeoning universe of underground comics.

Underground comics (or comix) were exploding.

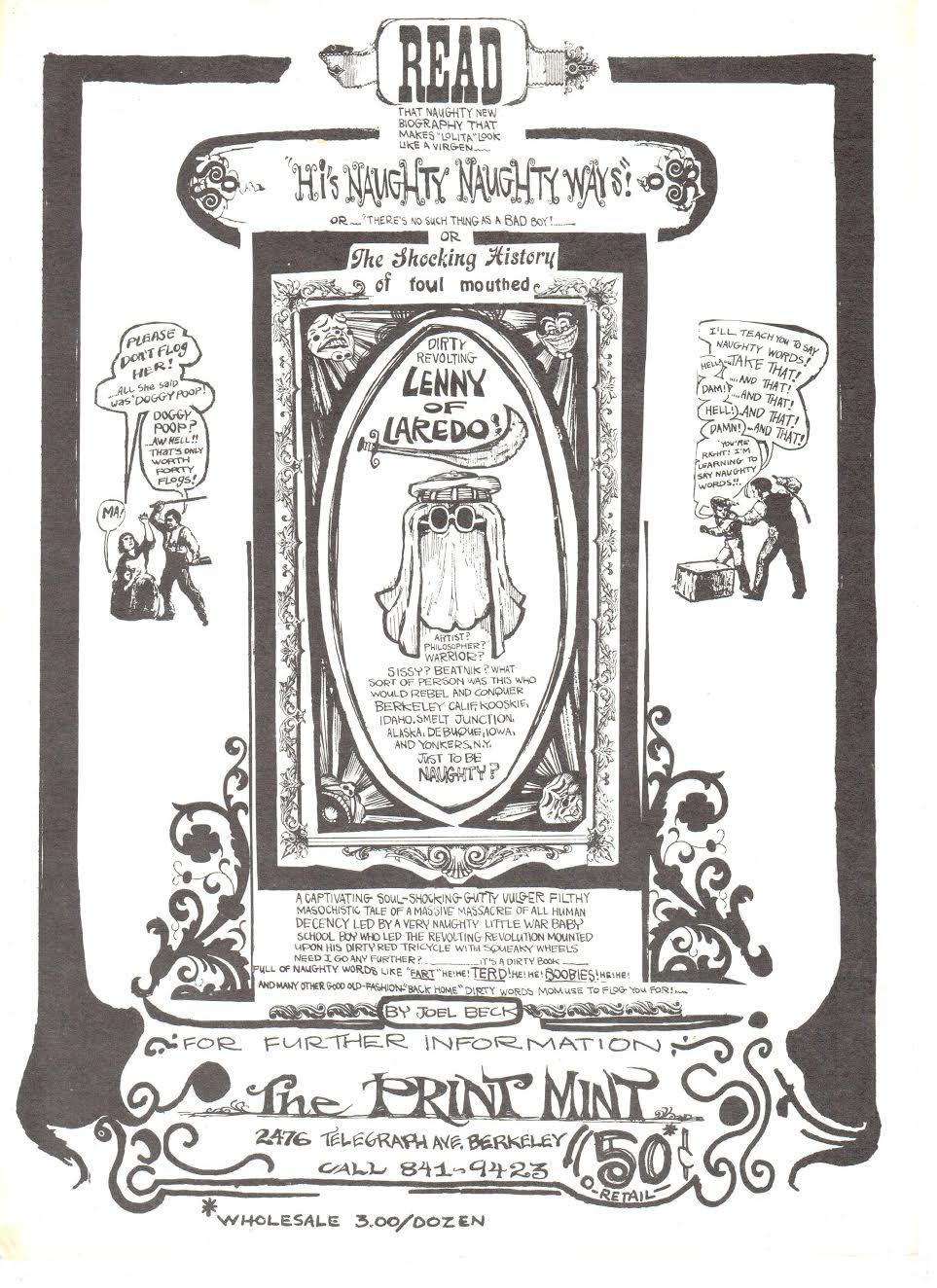

Schencker’s first comics job was an April 1966 reprint of Joel Beck‘s Lenny of Laredo, but comics weren’t a big part of the business until a few years later..

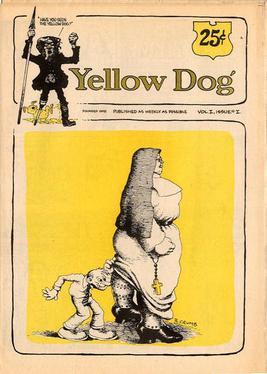

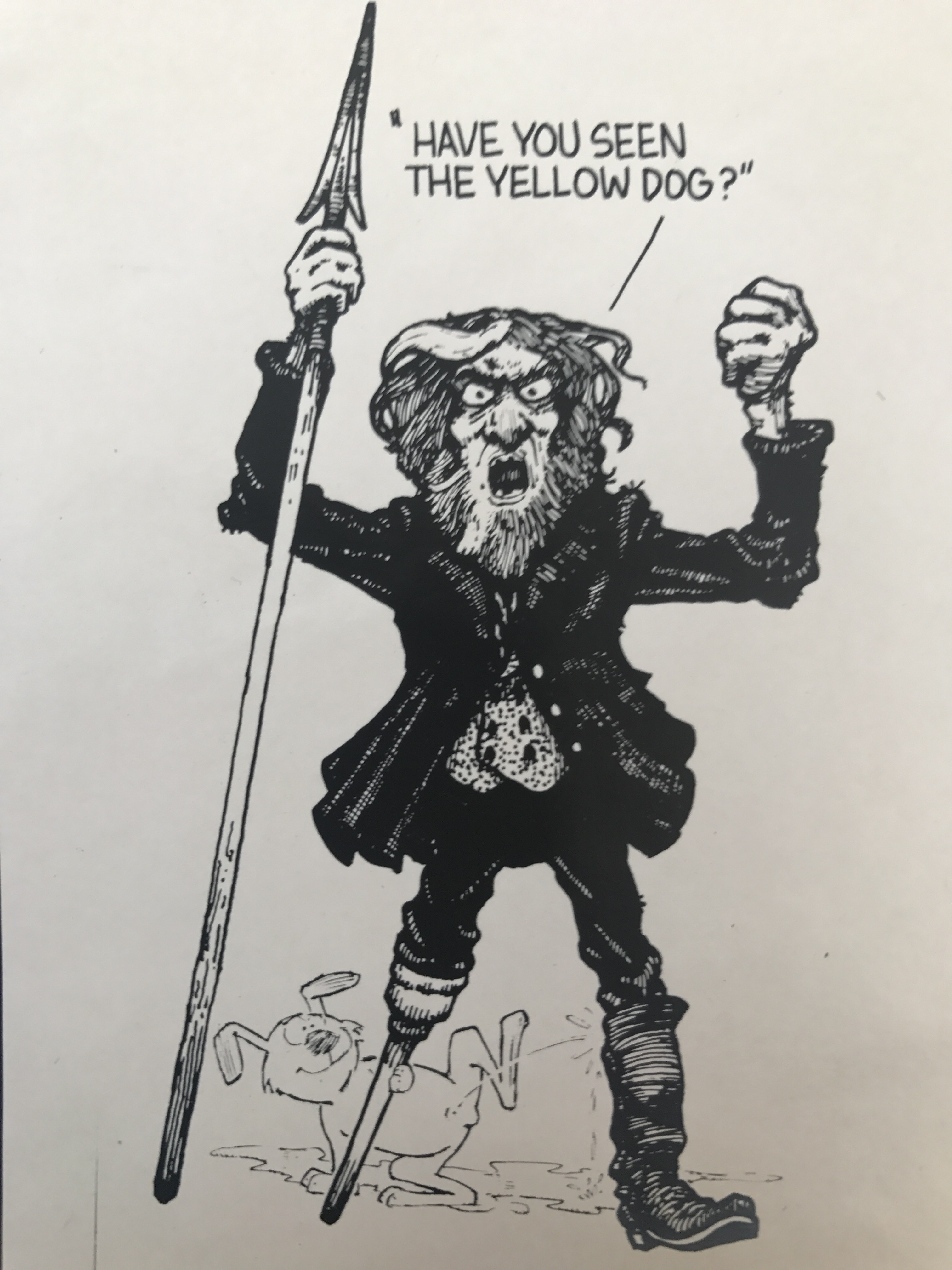

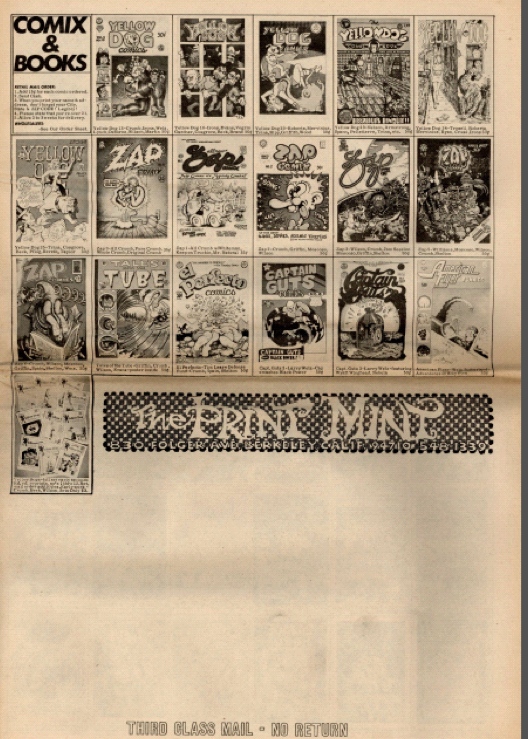

In 1968, Print Mint launched Yellow Dog, a newspaper and then comic book that featured many of the superstar artists of underground comics.

In 1969, comics became the main deal for the business.

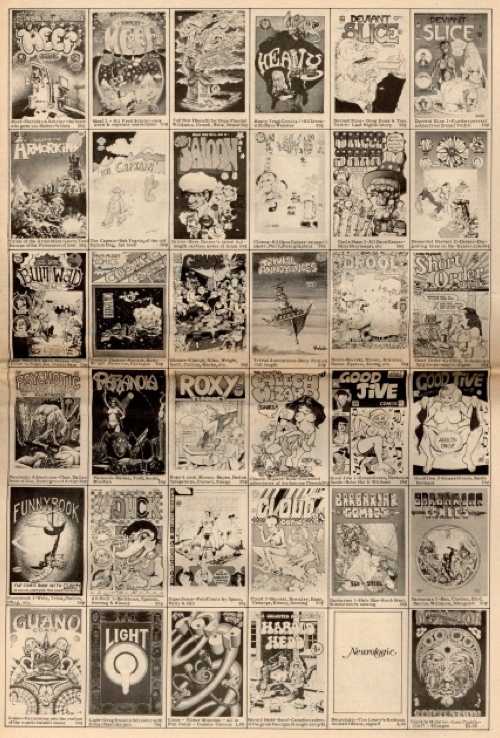

Eventually, the Print Mint published such underground stars as Robert Crumb, Trina Robbins, Rick Griffin, S. Clay Wilson, Victor Moscoso, Gilbert Shelton, Spain Rodriguez, and Robert Williams.

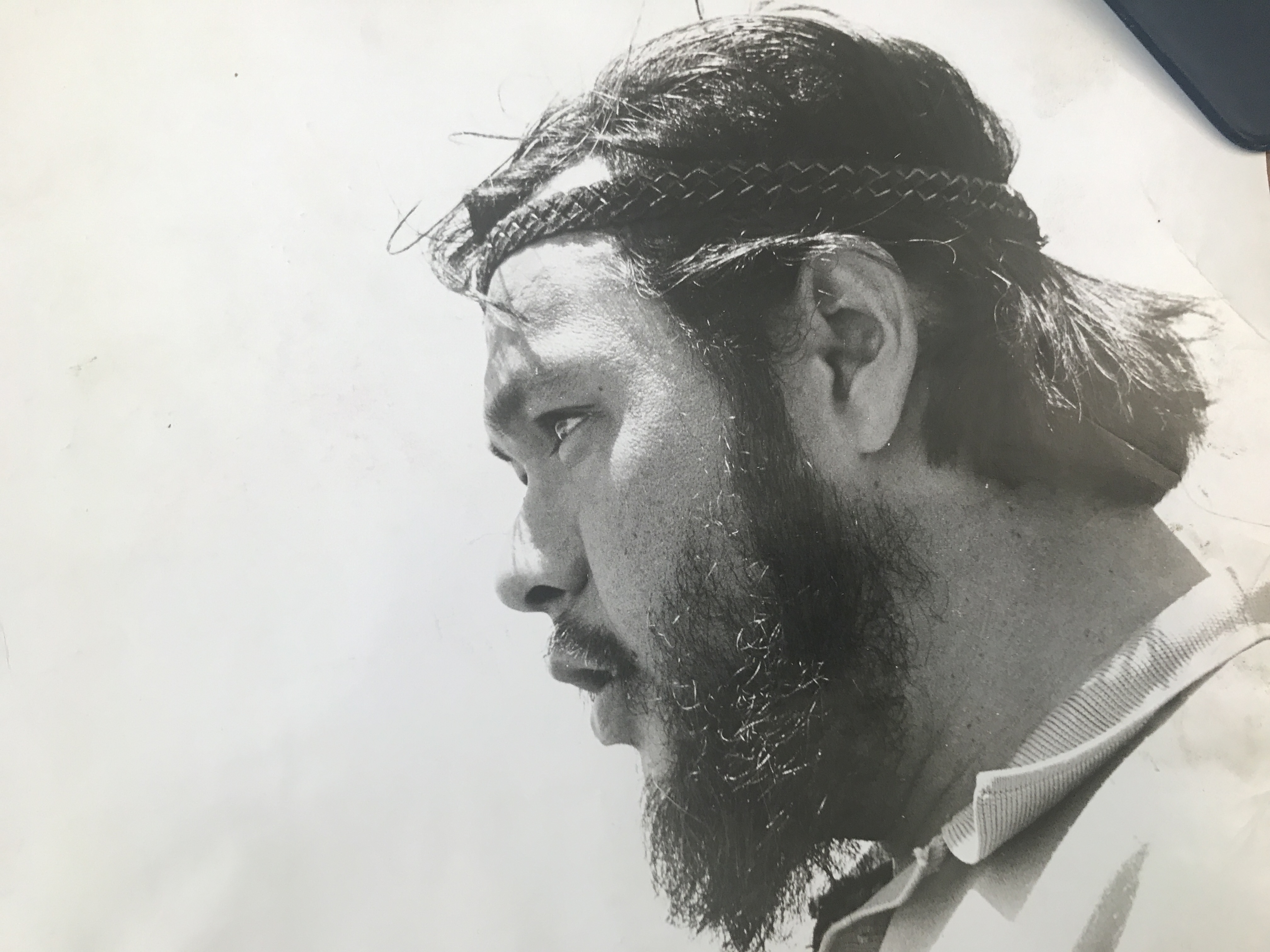

Shown here are Print Mint comix artists. Top Row, L. to R.—Andy Martin, Jack Jaxon, Victor Moscoso, Franz Cilensek, Robert Crumb, Spain Rodrigues. Bottom Row, L. to R.—Gilbert Shelton, Don Schenker, Rory Hayes

As the comics took off, Don and Alice made Bob and Peggy Rita partners. It was Don’s hope that each couple could work for six months and then take six months off. That sounds good, but it didn’t work out that way.

Don did the organizing, editing and layout of the comic books, working with the artists. Bob and Peggy Rita and Alice handled the distribution and the day-to-day operations of the business. Alice also oversaw the Berkeley store.

The company’s main office was located at 830 Folger Avenue in Berkeley.

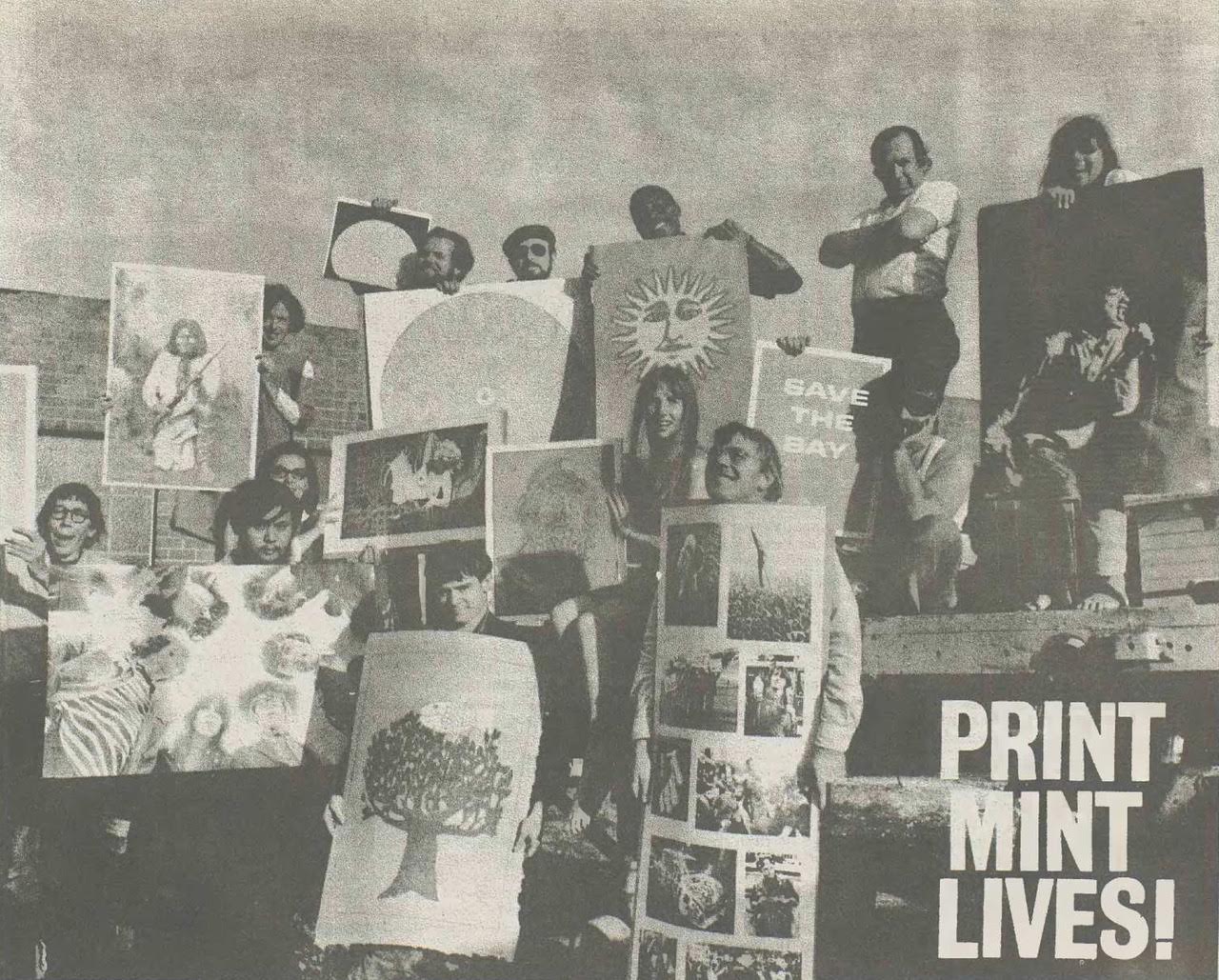

Employees and at least one artist gathered behind the Folger Street building for this photo. R. Crumb slouches with hat and tie in the back row.

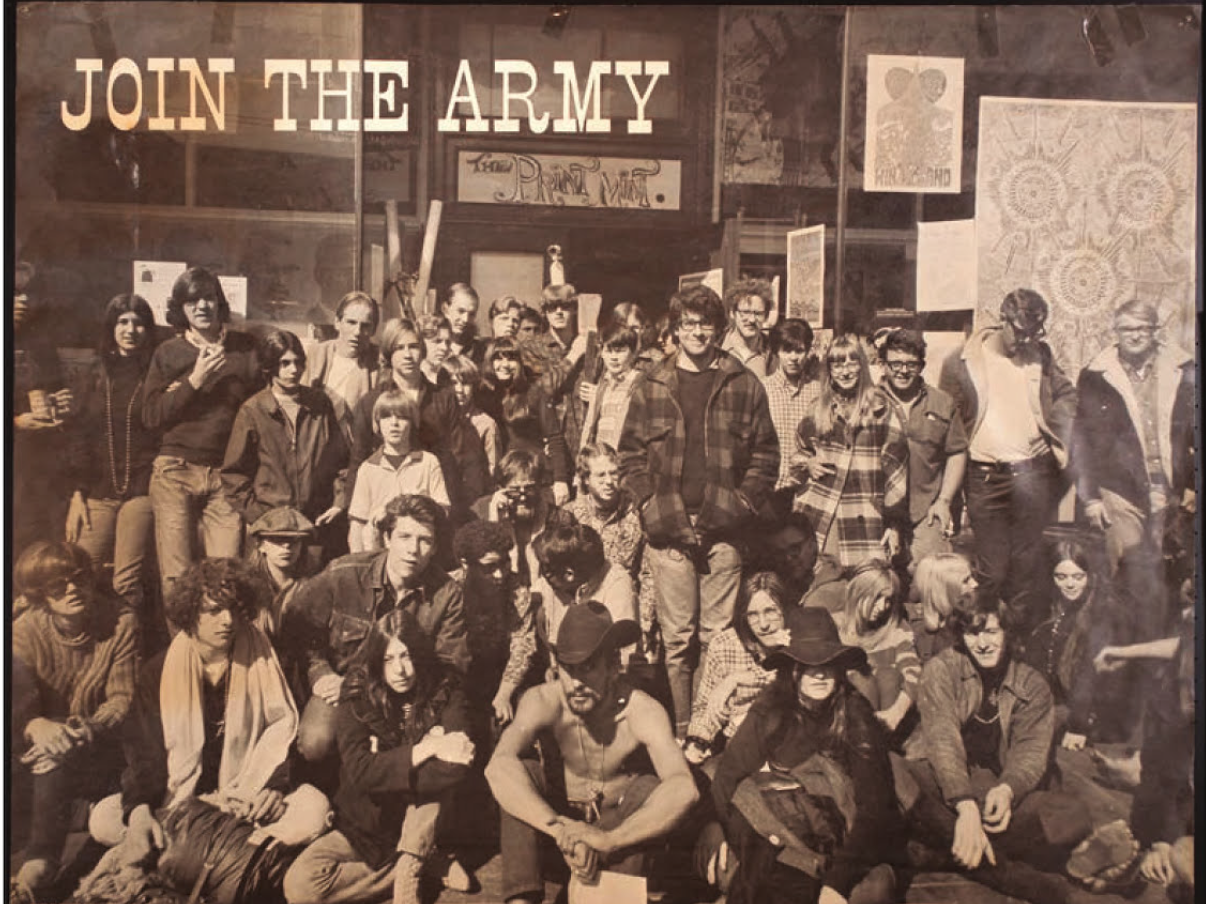

The photo for this Print Mint poster was also taken at Folger. Among those in the photo were Alice Schenker,Scott Smiley, Lewis Rubman, MelFleming, Lisa Von Stauffenberg, Phil Gardener, Bob and Peggy Rita, and Don Schenker (arms crossed in the upper right).

Publishing and distributing underground comics was not without its risks, as the Schenkers learned.

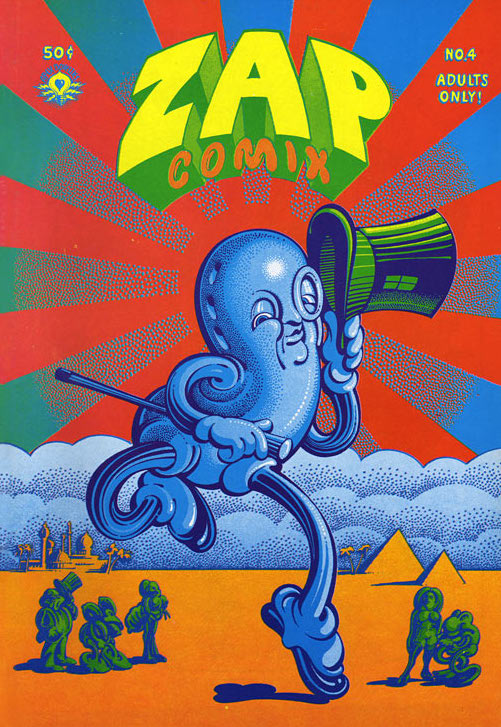

The first issue of Zap that they published was #4 in the fall of 1969.

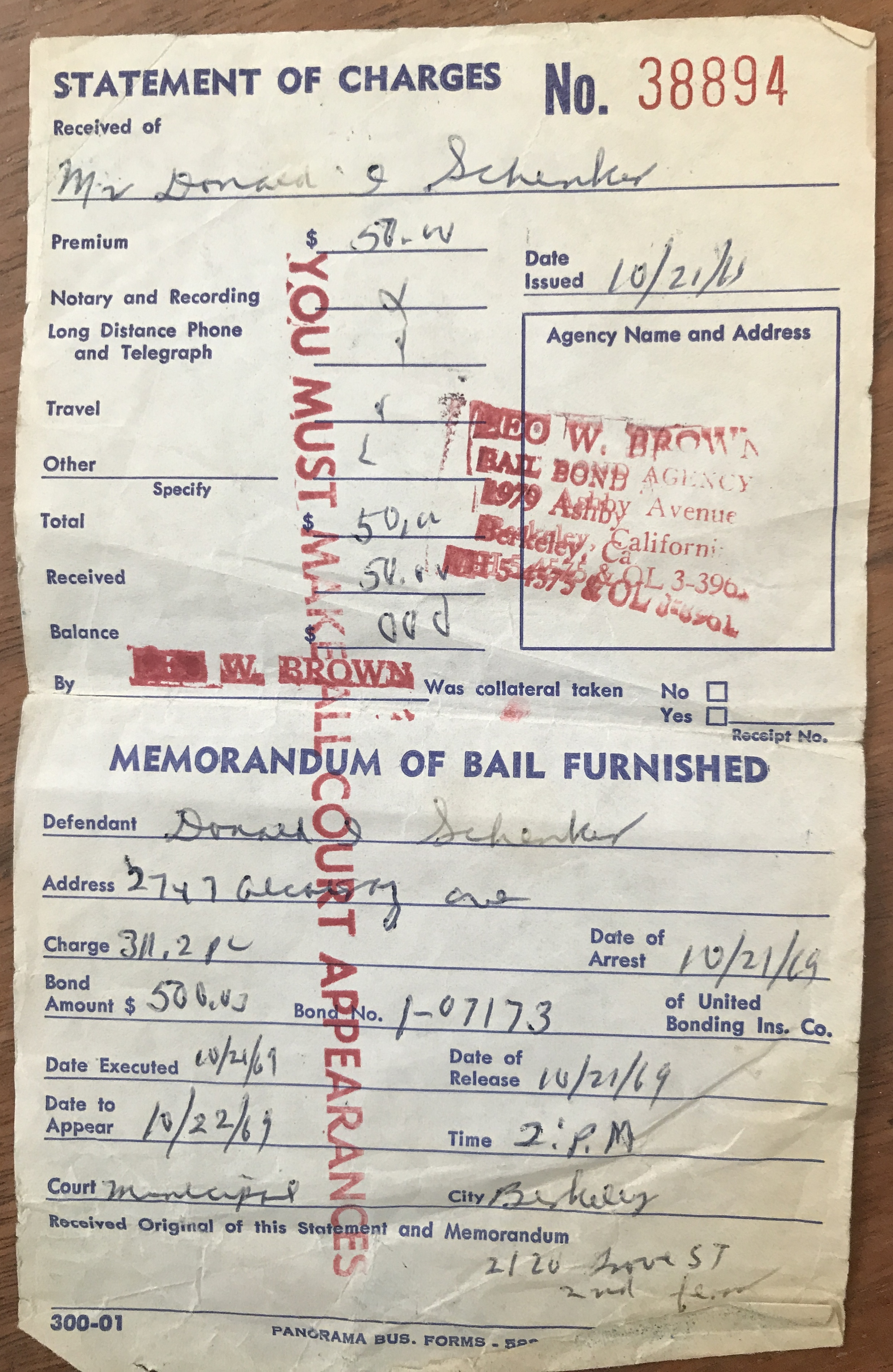

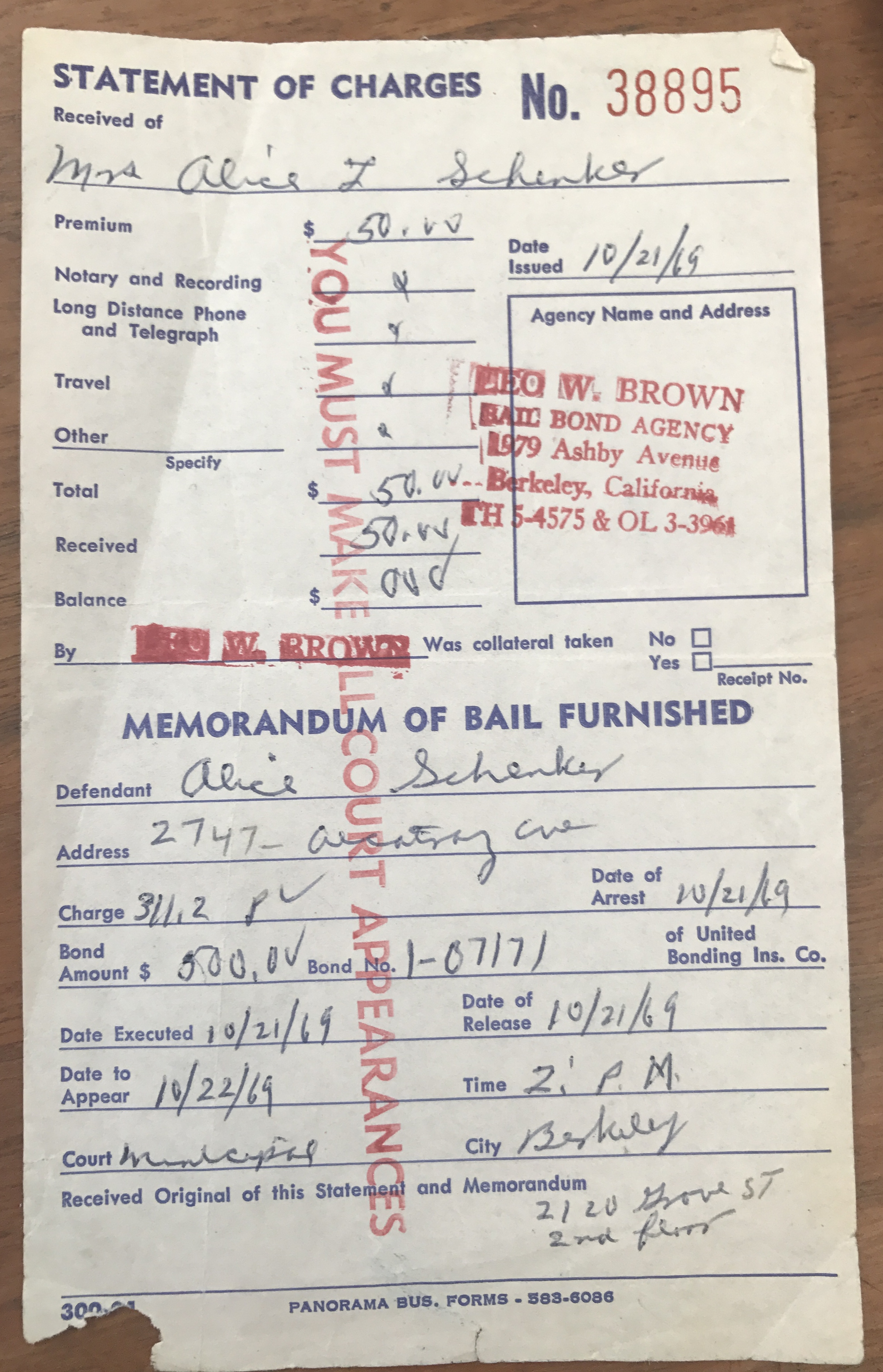

One of the themes that R.Crumb explored was incest in a “normal” middle-class family. The Berkeley Police arrested the Schenkers on October 21,1969, and charged them with publishing pornography.

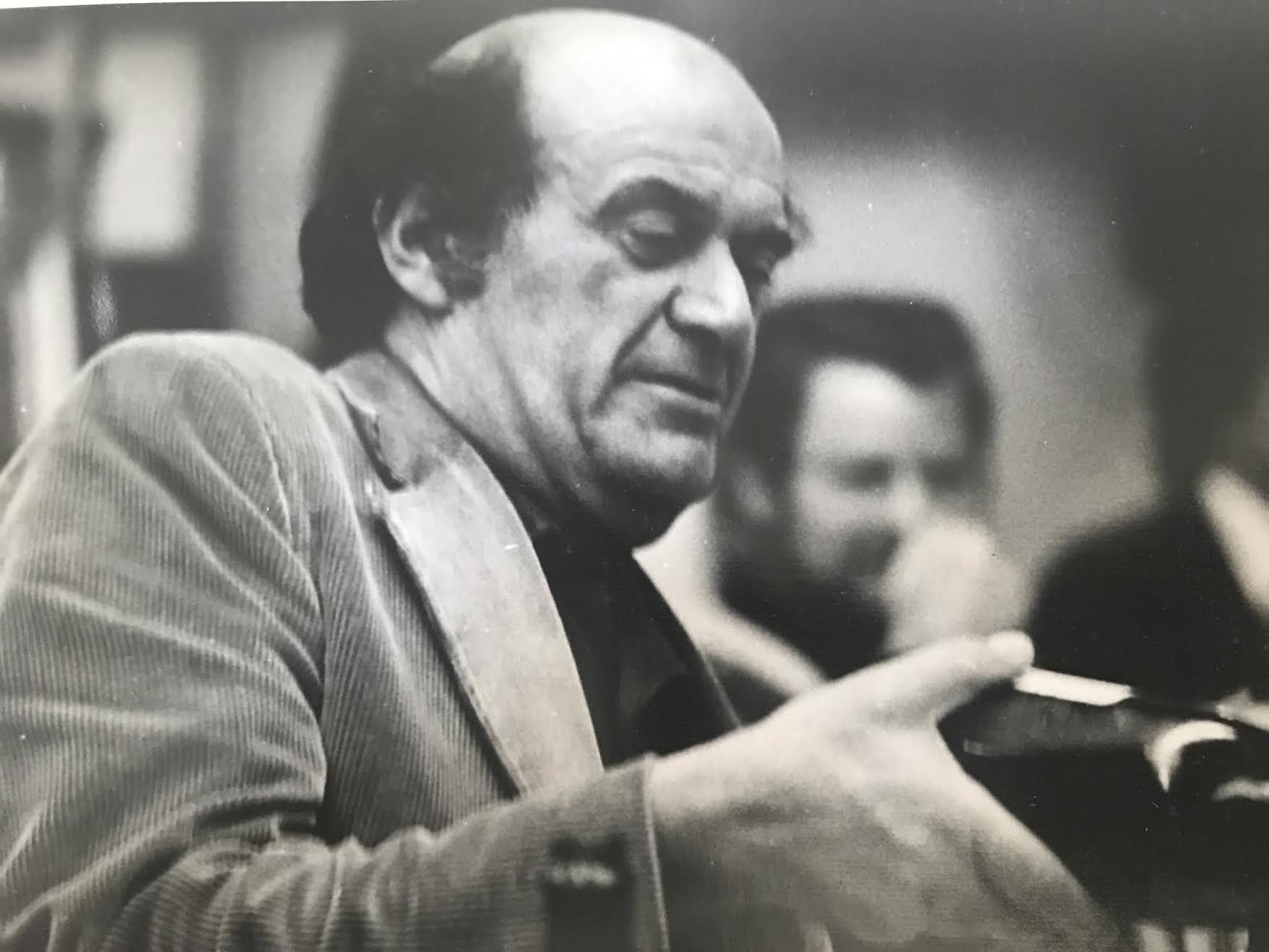

Their friend Simon Lowinsky, who had a gallery on College Avenue and had put up an exhibition of the Crumb’s original drawings, had been arrested on the same charge. His case came to trial first. He was acquitted[ after supportive testimony from Peter Selz, a Cal professor. The charges against the Schenkers were dropped.

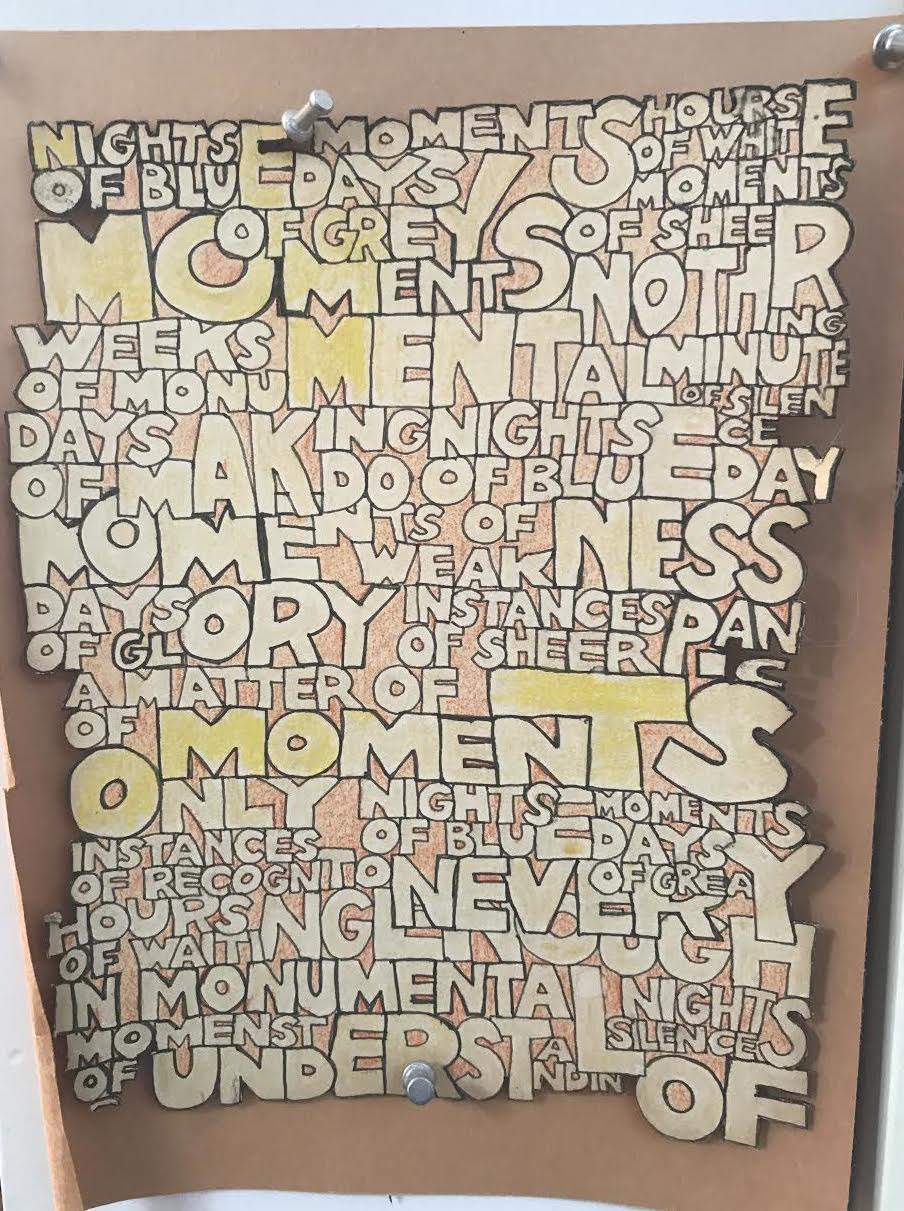

Don Schenker had never stopped writing poetry. In 1970 he published Say X, complete with a blurb on the back: “Schenker’s talent staggers me. His range is enormous…” Did I mention that he wrote his own blurb?

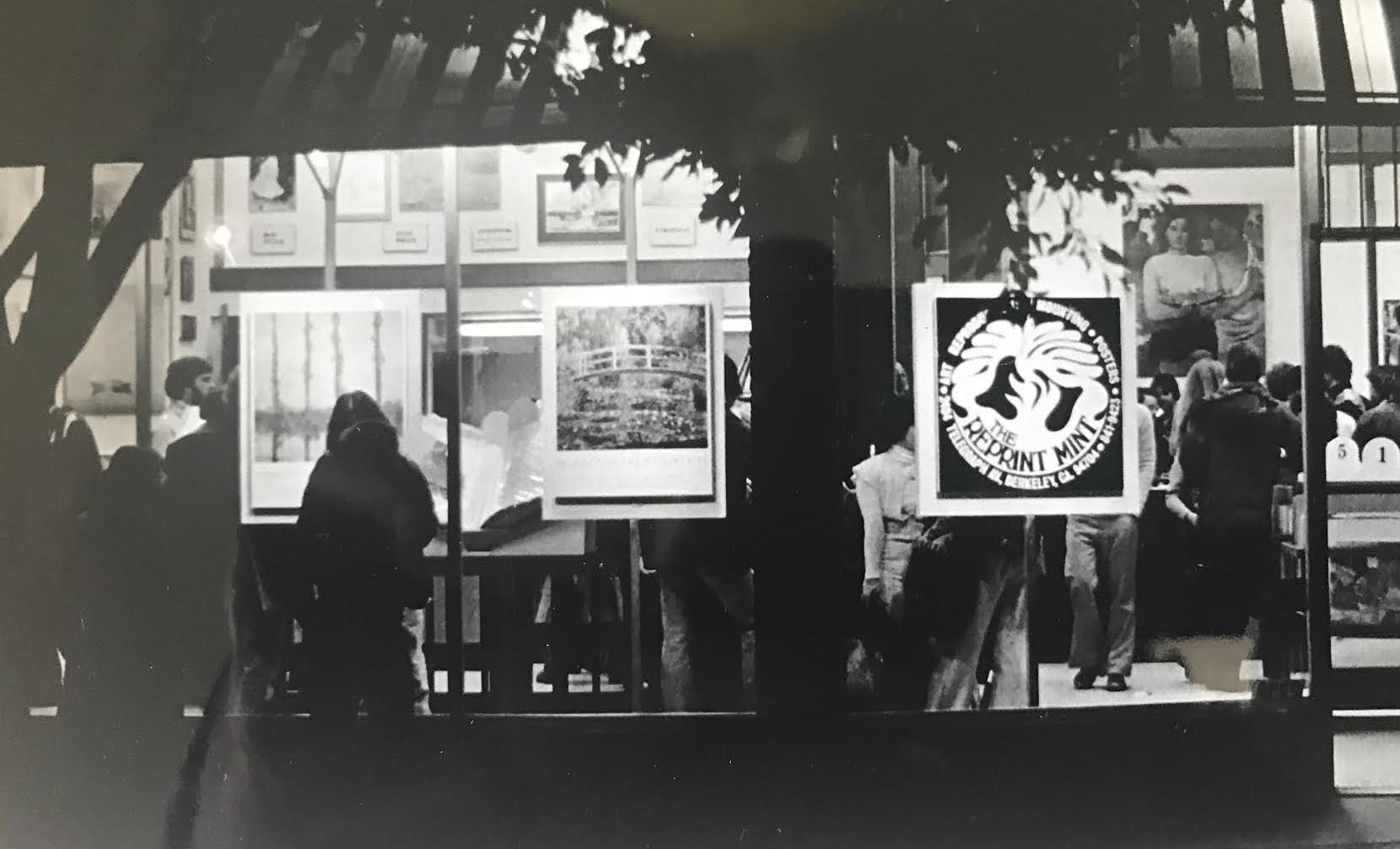

The Schenkers rode the wave of Print Mint in its full-throttle glory until 1975. In 1975, the Schenker/Rita partnership dissolved. Rita took the publication/distribution end of the business, and the Schenkers the store and framing. The Rita end of the business retained the Print Mint name, and the Schenkers renamed the store the Reprint Mint.

Jack Foley wrote this about Don and his state of mind:

By 1975, Schenker had become a “businessman”—he gave the word a negative charge—and wrote very little. He felt isolated, he told me, and had the sense that people “hated” him, “perhaps because [he] was in business.” Years earlier, Jack Kerouac and Charles Bukowski had urged him to be “free,” even to leave his wife and family. Kerouac told him, “You’re such a nice guy, Schenker. That’s your problem.” Schenker felt the call of such freedom and later decided that at some level Kerouac was right: “I felt in my young days that it was much safer to be tight and in control”; Kerouac was pointing to “things I probably feared.” But he didn’t take the advice.

After another ten years, the Schenkers sold the business completely. The Reprint Mint changed hands once, and lasted until late 2016 when it closed suddenly.

Within days of selling the business in 1985, Don was diagnosed with metastasized prostate cancer. He continued writing poetry and published two books – Up Here (1988) and High Time (1991).

And he made word pictures. Don died in 1993.

Alice lives on in Berkeley, with art around her.

She paints.

I asked Alice about the fact that she and Don rode the wave of the Beat movement and then were at ground zero of the hippie movement on Telegraph. She smiled her smile to die for and shrugged her shoulders. Yes they did. Yes, it was a remarkable journey.

I have come to appreciate the modest strides out from the shadows that occurred in every facet of culture during the 1950s, the conventional perception of the decade as stifling and conformist and bland notwithstanding. The Schenkers were there, in Greenwich Village and North Beach, the two great hubs of beat culture.

And then the Big Changes – the excesses of the 1960s. Telegraph Avenue in the late 1960s was an artery of the counterculture. They were there, selling James Dean and W.C.Fields posters and then rock posters and underground comics. Right in the heart of it all.

They were there. Part of it.

Oh my. I can feel their youth and joy and excitement and courage and their capacity to see beauty – to my bones, to my heart. The Schenkers kept that joy and excitement and courage as they aged. Kafka wrote that anyone who keeps the ability to see beauty never grow old. So be it – let us see beauty and stay young.

There is an aura around Alice Schenker. She has seen so much and done so much and made so much and lived so much. She is Berkeley, the Berkeley that brought us here, that we love, that we stay for.

I asked my friend to take a look at the draft post. He walked me into his living room.

“Humbead’s Revised Map of the World created by Earl Crabb and Rick Shubb. Had the Print Mint frame it in ’69. Had it up ever since.” It’s a dandy poster to be sure. I’d love one. It would do well on a wall of Special Berkeley Posters, no?

I returned to the pending question to my friend. What about the post? “The Beats. The Summer of Love on Haight. Telegraph all those years. Zap. Crumb. Busted! What can I say?” He found the words though –

Thanks for this on the Print Mint. Would be great if you got together with Lincoln Cushing and did a piece on Inkworks.

https://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/inkworks-press-1974andndash2016/Content?oid=4673190

So nice that the Schenkers get there due in this piece. They were instrumental in creating the vibrant culture of the time….and are/were lovely decent people whose sense of the absurd kept the ship afloat.

I very much enjoyed the article.

Any idea what happened to Zach Lowinski.

Jan

I very much enjoyed the article.

Any idea what happened to Cy Lowinski.

Jan

very cool, interesting, i went through kindy to 4th on 19th and 20th across from golden gate park and lakeshore elementary by the zoo and gatorville from 69-75 and mr schenkers right it was one trippy ride, one that some embraced and one that some would have rather forgot, but any way you cut it, it happened undeniably, for better or worse, for strange or straight right or wrong justice or abuser and culminating in nothing dissappearing almost without a trace only to be rediscovered once again by a curious cat that tips his hat, hows that

Loved this article,Don got me into a few Yellow Dogs,my first time published.