As Mr. Peabody used to say to Sherman on the “Peabody’s Improbable History” segment of The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show, “Set the Wayback Machine to 1969!”

Today is a holiday which means that it’s time for a Quirky Berkeley notional field trip. Instead of a trip through space and place, today we will time-travel to 1969. It is, after all, Memorial Day, a day of public remembering.

It was Memorial Day 1969, Friday May 30 to be exact. It was the final scene in the powerful first act of People’s Park.

Work began on People’s Park on April 20, 1969. A year earlier the University had demolished the houses that lay within the block formed by Telegraph, Haste, Bowditch, and Dwight. For the intervening year the University had done nothing to develop the land.

Between April 20 and May 15, 1969, thousands of people spontaneously transformed the soul-sucking eyesore of a vacant lot into a pleasant, relaxing, and slightly chaotic park. Volunteers laid sod, planted flowers and trees and bushes, built an amphitheater, laid out winding brick paths, and installed swings and play structures. The people who built the park included hippies and freaks and Yippies and street people and politicos and radicals and peace activists and the Free Church of Berkeley and environmentalists and students and grad students and professors and architects and neighbors and children

The Park as originally created last 24 days.

On May 15, the University fenced in the Park and began dismantling the work that had been done. Later that day, law enforcement officers armed with shotguns shot up Telegraph Avenue as Park supporters protested the University action. A Sheriff’s deputy shot and killed James Rector, a bystander. A Sheriff’s deputy shot and blinded Alan Blanchard, a bystander. A Sheriff’s deputy gut-shot Donovan Rundle, a bystander, from close quarters. Law enforcement officers, mostly Sheriff’s deputies, indiscriminately shot dozens more, mostly bystanders.

On May 16, more than 2,000 Army National Guard troops entered and occupied Berkeley. A strict curfew and ban on assembly were declared. Bayonets, barbed wire, and military vehicles were the new normal.

On May 20, a National Guard helicopter teargassed Sproul Plaza. The gas drifted north as far as Oxford School and south as far as Emerson School. It filled University classrooms, libraries, and Cowell Hospital. Thousands were affected.

On May 22, law enforcement boxed in and arrested almost 500 people on Shattuck Avenue. Some were protestors. Many were not, they were just caught up in “Operation Box.” Those arrested were taken to the Santa Rita Jail in Dublin. Guards physically abused prisoners to an extent that led to a federal injunction, federal indictments, and internal Sheriff’s Department discipline.

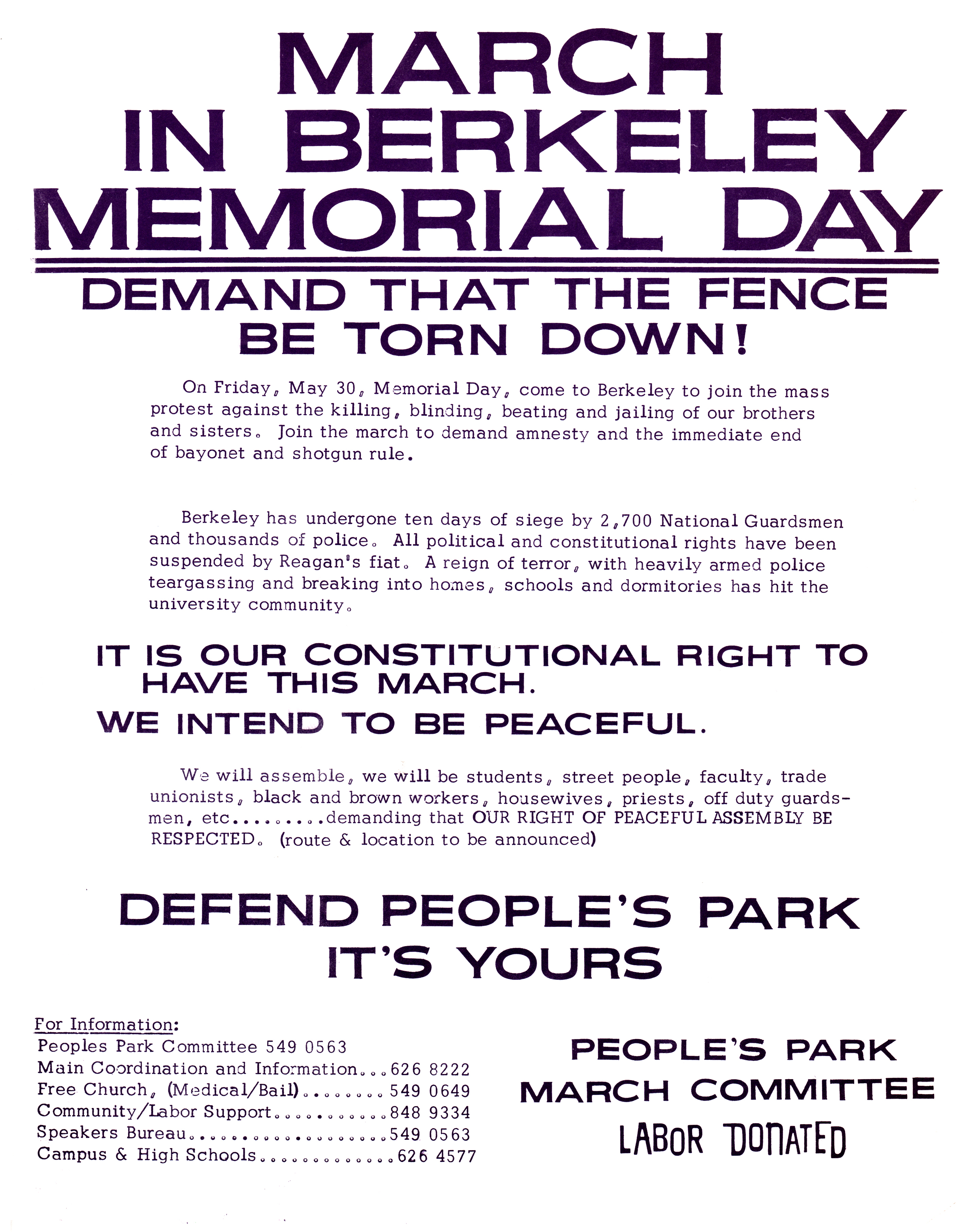

The loosely knit leadership of the People’s Park movement then announced plans for a Memorial Day march to be held on Friday, May 30. Bill Miller, a Telegraph Avenue merchant and leader of the Provo Party, secured a permit for the march

Almost as soon as the march was announced, Alameda County Sheriff Frank Madigan and Governor Reagan vowed that law enforcement would use shotguns again if the march got out of hand.

Fred Cody of Cody’s Books was concerned about the potential for violence. He reached out to Roy Kepler of Kepler’s Books in Menlo Park and the local Quaker community. Peace activist Peter Bergel was recruited to train marshals for the march. As many as 800 people went through the training the night before the march at Le Conte School. Local Quakers bought 30,000 daisies that were distributed to marchers, leading to many instantly iconic photos of daises and barbed wire, daisies and bayonets, daisies and National Guard etc. Men and women who would go on to lifetimes dedicated to non-violent resistance were here, maintaining the peace – Mandy Carter, Randy Keeler, Steve Ladd, and many others.

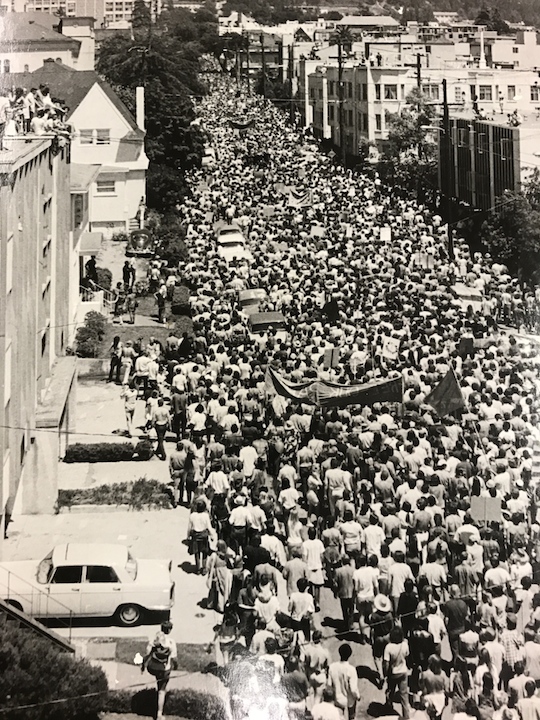

The march was huge.

Estimates ranged up to 30,000 marchers. It is the largest demonstration in Berkeley’s history.

The march was peaceful and nonviolent and there were only a few scattered arrests. It was Berkeley Big Love in action.

Some found the march exhilarating, an affirmation of Berkeley’s ability to maintain discipline and unity and nonviolence despite state violence and provocation.

Others found the march a failure, a co-opting of a militant resistance to state violence that failed to change anything about the University’s occupation of the Park.

I am more than ever aware of the different cities called Berkeley – the city as it existed in the past, the city as it actually exists, and the city of our imagination and the nation’s imagination. Forty-nine years ago, the city that existed was one in which 30,000 people would join a march to demonstrate resistance to shotgun shootings of innocent bystanders, helicopter tear gassing, military occupation, and illegal mass arrests. That became the Berkeley of the nation’s imagination. Is it the Berkeley that exists today? Would we do today what we did then? I hope so.

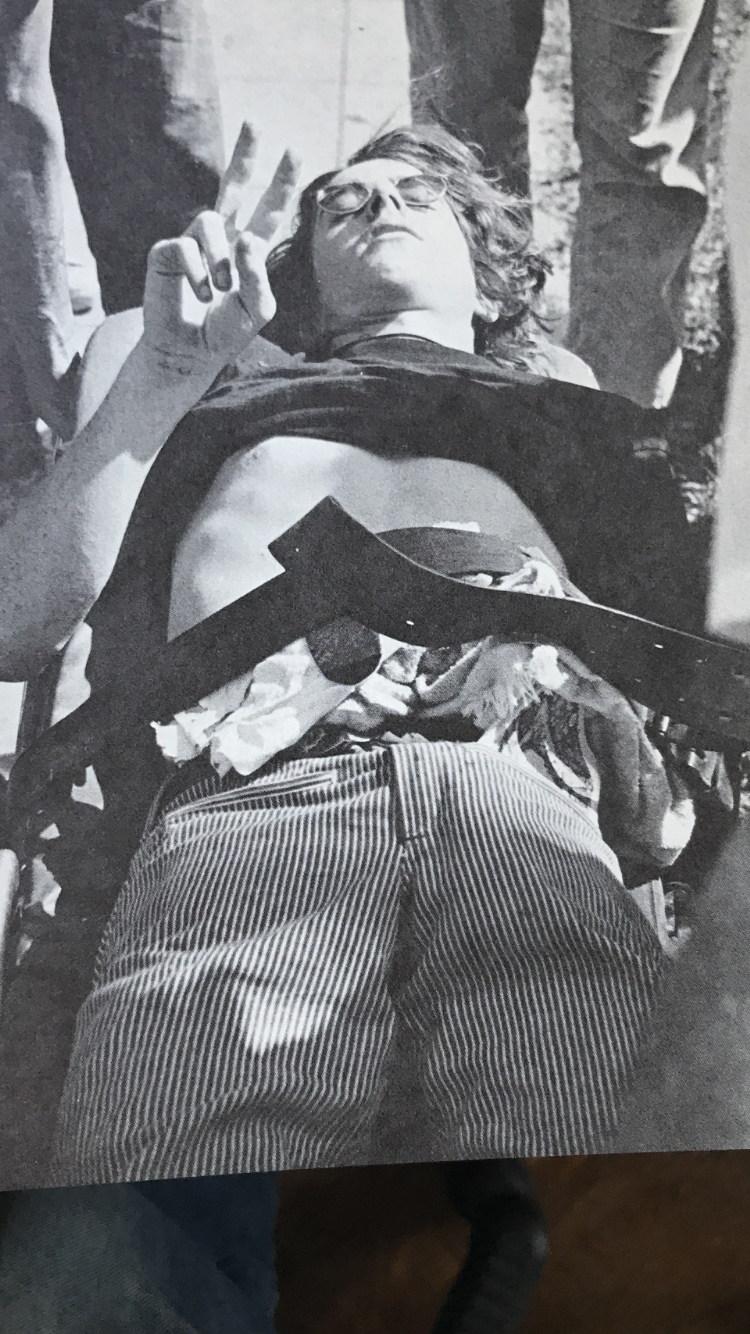

One of those whose courage we celebrated and whose shooting we condemned on the march was Donovan Rundle, a first-quarter freshman trying to return to his dorm room and carrying a copy of The Tempest, who on May 15 was shot at close range by a shotgun loaded with buckshot.

Rundle nearly bled out lying on Parker Street. His intestines were oozing from his eviscerated abdomen. Mario Savio, who by circumstance was nearby, shielding Rundle from further police violence. Neighbors on Parker and Chilton carried him inside a house, sheltering and comforting him until an ambulance arrived.

As he was loaded into the ambulance, Rundle flashed a “V” sign.

That is something to remember this Memorial Day – the Berkeley that had moral outrage and the first-quarter freshman with the courage to assert hope while on a stretcher and the neighbors who took him off the street and gave him comfort and support in a very dark few minutes.

That is the Berkeley of my imagination. The slogan of the French workers and students who took part in the May 1968 uprising was “All Power to the Imagination!” I agree.

I showed the post to my friend.

He got wistful. “Memorial Day makes me think of Whitman.”

He recited the opening lines of When Lilacs Last in the Door Bloom’d – “When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d / And the great star early droop’d in the western sky in the night / I mourn’d, and yet shall mourn with ever-returning spring.” He almost whispered another line – “Lilac blooming perennial and drooping star in the west.

I had not heard him recite Whitman in all the years we’ve known each other. Live and learn.

“And,” he continued, “You know that it was the WABAC machine not Wayback, right? And that Rock and Bullwinkle went off the air in 1964 and so Mr. Peabody never would have set the machine back to 1969? I get it – cool graphic, cultural allusion, but just so you know that you have some technical problems.”

Points taken. On the whole, though, what about this time-travel post?

Excellent Tom….I was there and I would do it again.

Doug

I was there, too. I have a few pictures somewhere. Funny how 30,000 just dissolved once we reached the Park. I remember rolls of turf in the street..

Thanks for eliciting those memories, Tom.

It was indeed a massive peaceful demonstration, an odd juxtaposition against the violence of the police riot of the previous weeks.

The feeling of community solidarity for all of us was palpable, which gave us a quiet strength.

Possibly as a result, the police were remarkably calm that day, and didn’t attempt to arrest any of the small group of people who armed with picks, who started to chip away some of the asphalt pavement of Dwight Way adjacent to the park in a symbolic act of defiance.

I had been involved with helping to build the park after school as my school, McKinley High aka Berkeley High East Campus, often sardonically referred to as Dwight Way College was conveniently located just west of Telegraph Ave. between Haste and

Dwight, where the Fenwick student housing co-op now sits.

I had been at the corner of Parker and Telegraph on the infamous Bloody Thursday 10 days beforehand and witnessed from a distance what turned out to be the shooting of innocent bystanders James Rector and Alan Blanchard by the “Blue Meanies” aka Alameda County Sherrif’s deputies.

During that same week, the Blue Meanies had strafed my schoolyard with shotgun fire during school hours, causing students and faculty to frantically scramble to safety.

Miraculously nobody was injured during the attack.

Later in that same week, I was savagely beaten by the CHP for the apparent crime of wearing long hair and a camera.

Reagan had declared an emergency and subsequent martial law and curfews, posting National Guard platoons on every corner of Telegraph Ave. and deploying armored personnel carriers, a tank and a howitzer at the Berkeley Marina.

Because of martial law, I had no legal recourse for redress and as a result became radicalized.

The Memorial Day march was a welcome respite from the chaotic strife of those awful weeks.