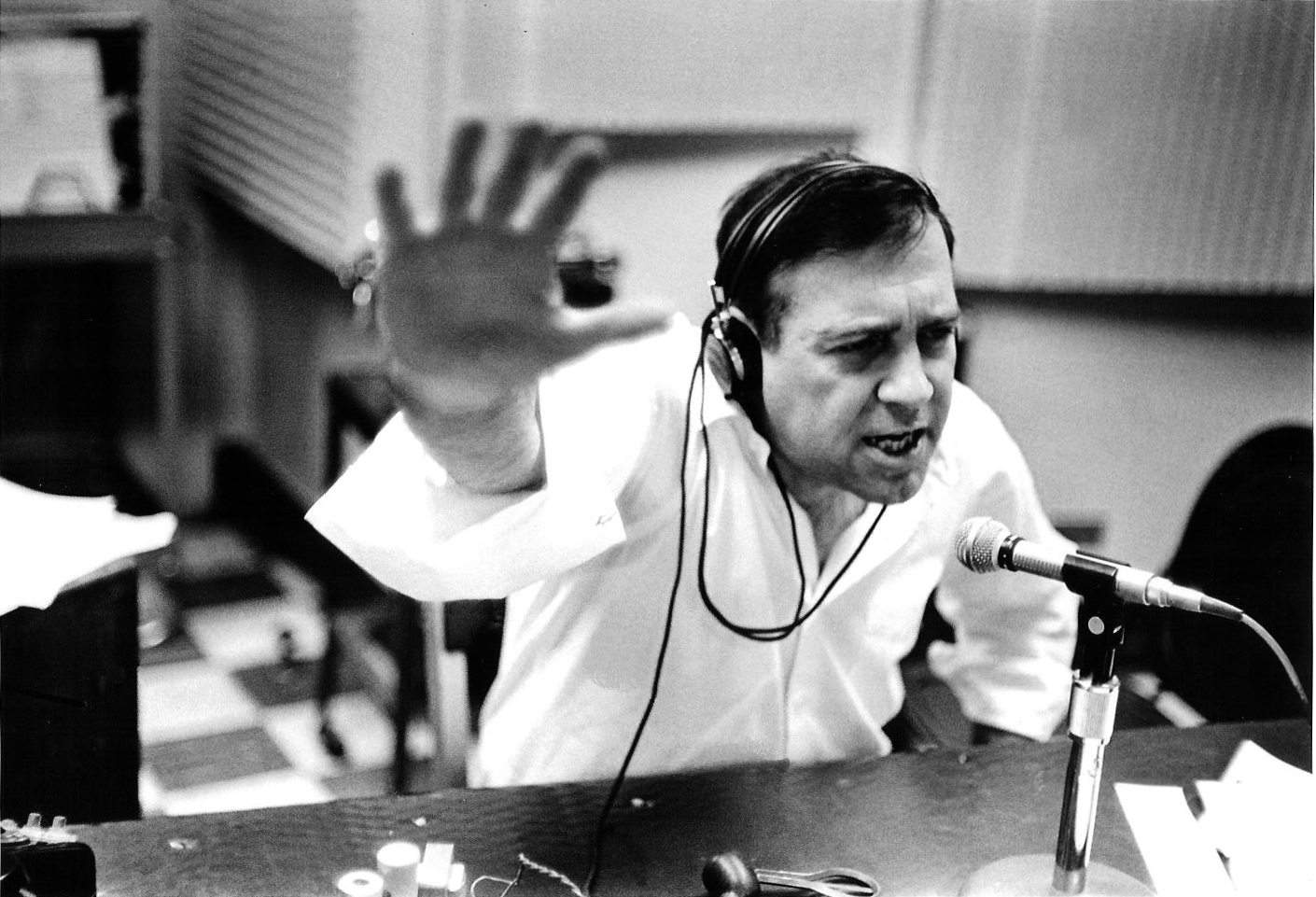

As I researched the disruptive, unconventional, and hetero orthodoxical voices of the American 1950s, I decided that any discussion of disruptive radio voices of the 1950s must start with Jean “Shep” Shepherd (1921-1999), the voice of the night in New York starting in 1955 when he landed a job with WOR radio. He was not a disc jockey who played music in any conventional sense of any of the words.

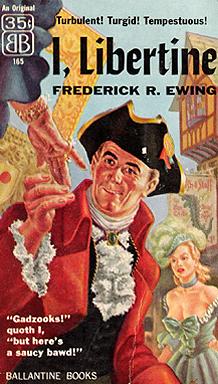

Shepherd was unscripted, extemporaneous, improvisational, and completely unpredictable. He loved jazz and sometimes played jazz records. He loved poetry and sometimes read poems. He loved the Pogo comic strip and sometimes read Pogo’s songs. He reflected, he contemplated, he commented, he told stories that were presented as truth but which were a combination of small part historical fact big part fancy. He engineered mass pranks such as hurling invectives or organizing “mills” (early happenings), and most famously by having his audience create a demand in bookstores for a non-existent book, I Libertine.

Shepherd was unscripted, extemporaneous, improvisational, and completely unpredictable. He loved jazz and sometimes played jazz records. He loved poetry and sometimes read poems. He loved the Pogo comic strip and sometimes read Pogo’s songs. He reflected, he contemplated, he commented, he told stories that were presented as truth but which were a combination of small part historical fact big part fancy. He engineered mass pranks such as hurling invectives or organizing “mills” (early happenings), and most famously by having his audience create a demand in bookstores for a non-existent book, I Libertine.

In 1964, Marshall McLuhan wrote that Shepherd was “the first to use radio as an essay and novel form for recording our common awareness of a totally new world of universal participation in all human events, private or collective.” McCluhan perhaps over-thought it, but he understood Shepherd’s tremendous impact on his radio audience.

In 1964, Marshall McLuhan wrote that Shepherd was “the first to use radio as an essay and novel form for recording our common awareness of a totally new world of universal participation in all human events, private or collective.” McCluhan perhaps over-thought it, but he understood Shepherd’s tremendous impact on his radio audience.

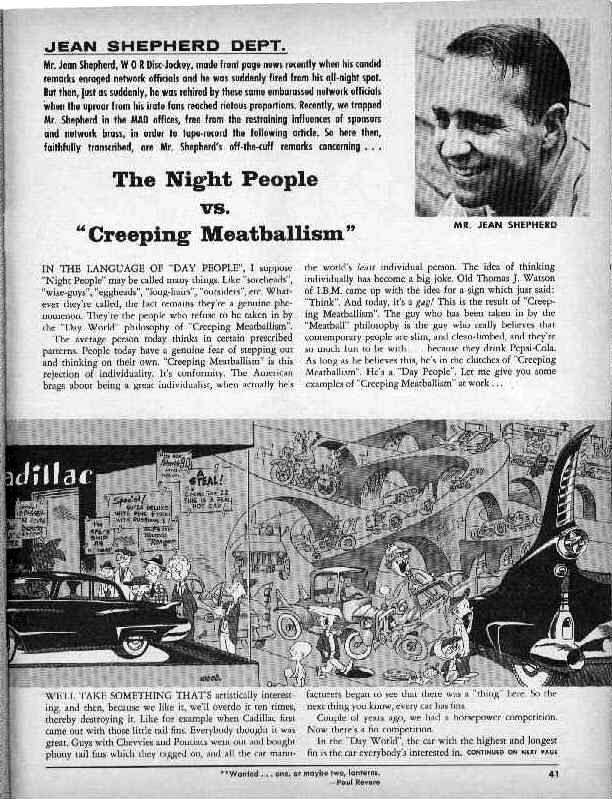

Shepherd was not overtly political, but he was deeply alarmed by the socially mandated conformity and sublimation of individuality, which he called creeping meatballism, around him, Shepherd wrote in Mad magazine: “People today have a genuine fear of stepping out and thinking on their own. ‘Creeping Meatballism’ is this rejection of individuality. It’s conformity. To conform or not to conform was the existential question for Shepherd, and he came down squarely on the side of not conforming, labeling those who chose to conform day people living in the day world. Day people were, in his lexicon, those unquestioning conformists who blindly accept the materialism, consumerism, and anti-individualism of the dominant culture. Back to the 1957 Mad Magazine, Shepherd wrote “The guy who has been taken in by the ‘Meatball philosophy is the guy who really believes that contemporary people are slim, and clean-limbed, and they’re so much fun to be with because they drink Pepsi-Cola. As long as he believes this, he’s in the clutches of ‘Creeping Meatballism.’ He’s a ‘Day People’.” The day world was simply the dominant culture, defined by unfettered materialism and unquestioned consumerism. “It is totally impossible,” Shepherd wrote in Mad, “in the ‘Day World’ to buy anything that’s ‘small.’ Even if you try.”

Shepherd identified with night people, those who question conformity, materialism, consumerism, and the status quo. The term was a cornerstone of Jean Shepherd’s life philosophy and the epitome of iconoclasm. Shepherd was quoted by John Crosby in the New York Times of August 8, 1956 describing night people: “There’s a great body of people who flower at night, who feel night is their time. Night is the time people truly become individuals, because all the familiar things are dark and done, all the restrictions on freedom are removed. Many artists work at night – it is peculiarly conducive to creative work. Many of us attuned to night are not artists, but are embattled against the official, organizing, righteous day people who are completely bound by their switchboards and red tape.” Shepherd was less focused on the clock when he described night people the 1957 Mad magazine article: “And I’ll say this: Once a guy starts thinking, once a guy starts laughing at the things he once thought were very real, once he starts laughing at T.V. commercials, once he starts getting a boot out of movie trailers, once he begins to realize that just because a movie is wider or higher or longer doesn’t make it a better movie, once a guy starts doing that, he’s making the transition from ‘Day People’ to ‘Night People.’” In his broadcast of June 10, 1960, Shepherd reflected on the term: “And you know, incidentally, it has bothered me so much what has happened to the term ‘night people,” which I have always regretted coining. This was a term that I coined, and I will stand accused and guilty of it. I’m talking about people with that wild tossing in the soul that somehow makes them stay up till three o’clock in the morning and brood.”

Shepherd was a first-class raconteur, and over the years he developed a private lexicon that his listeners came to understand and appreciate as markers of his storytelling craft.

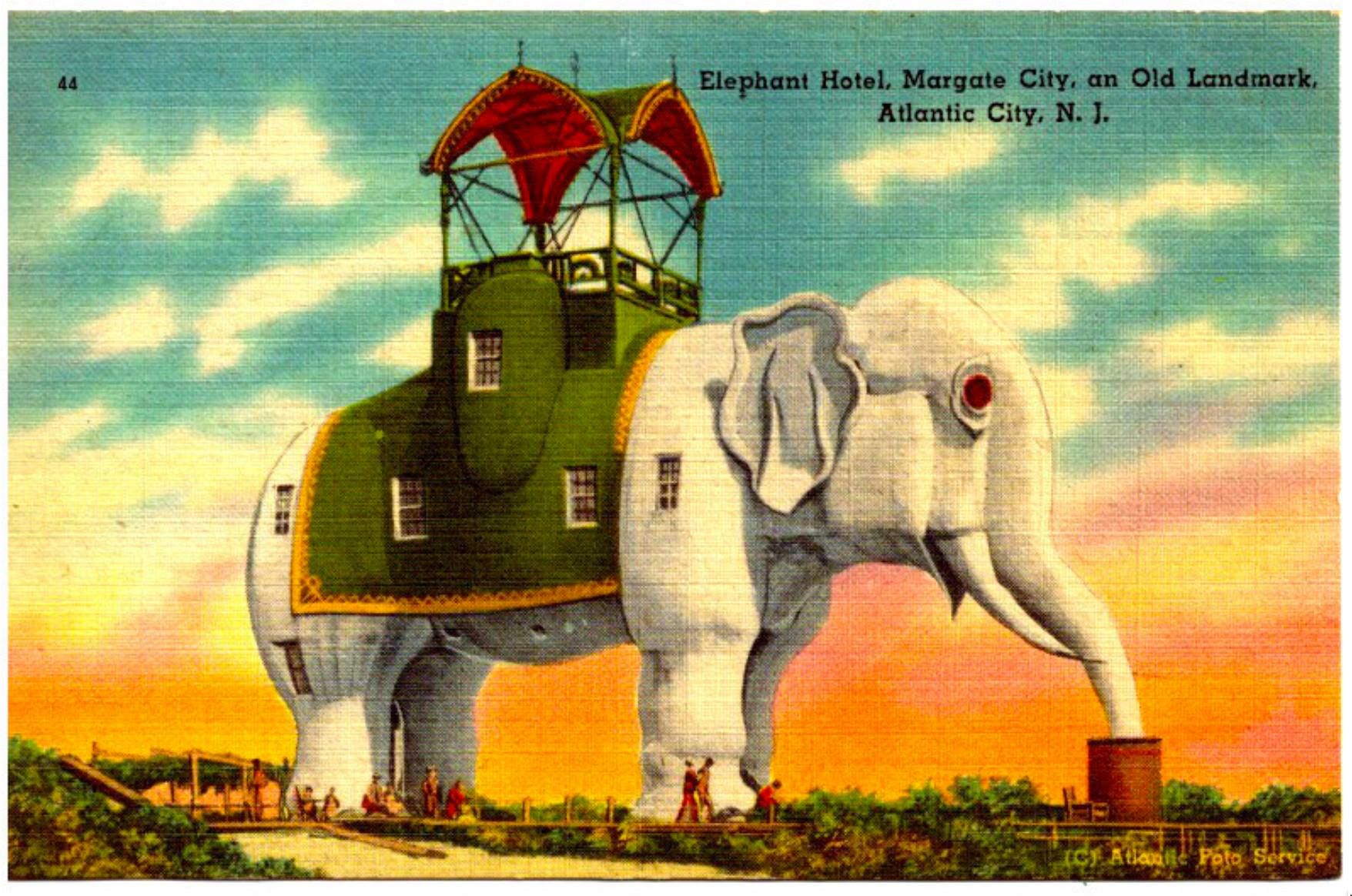

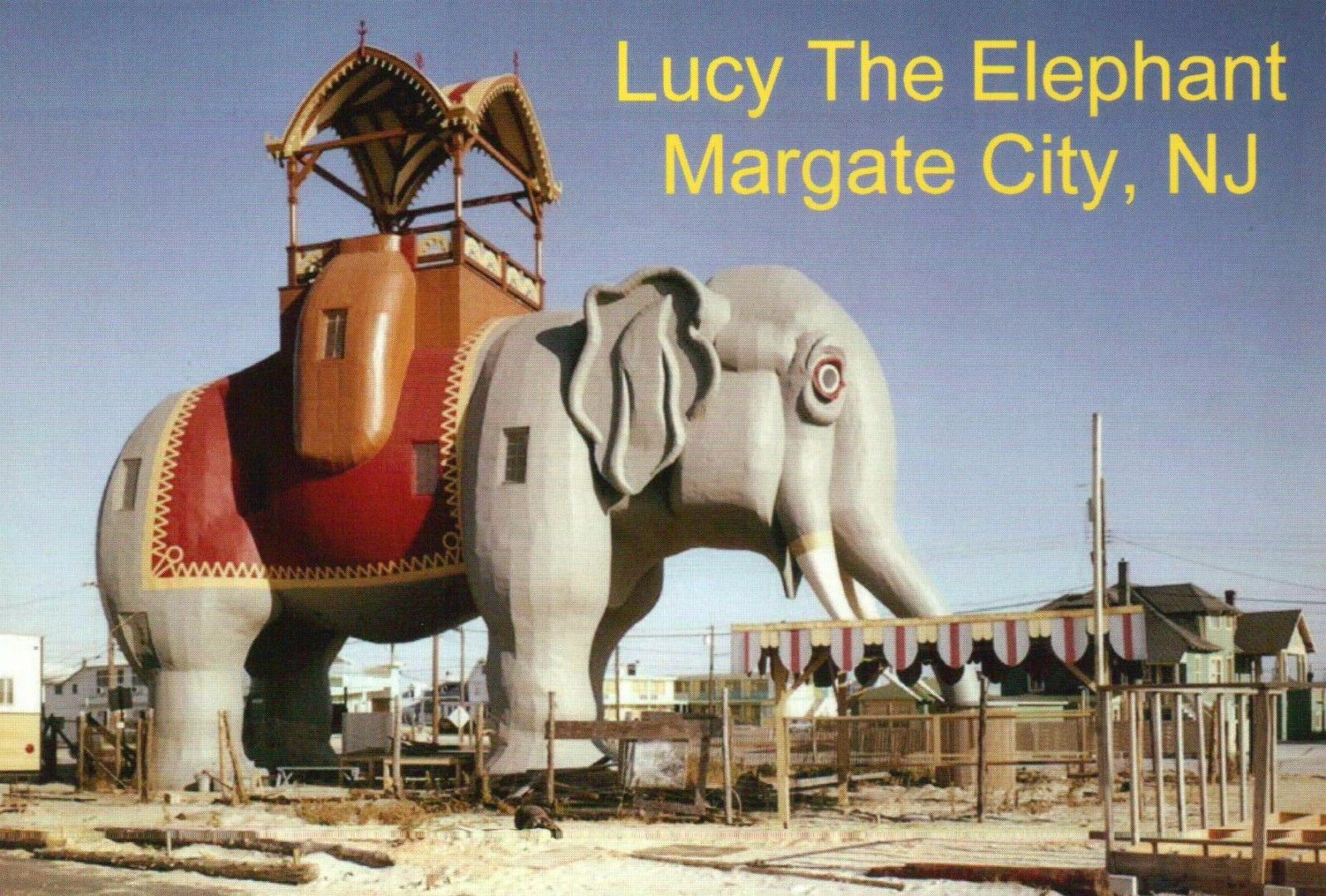

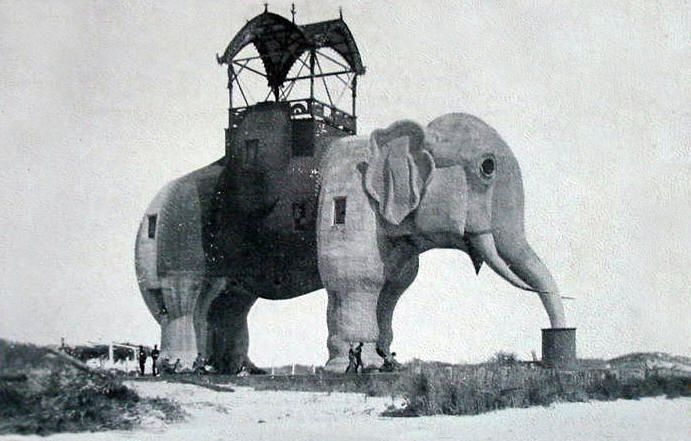

One such marker was was the Margate Elephant, a 65-foot high elephant-shaped structure in Margate, New Jersey, which was formerly a borough of South Atlantic City. To Shepherd, Lucy was “a true Jersey work of art” and New Jersey was a refuge from the stimulation and madness of Manhattan.

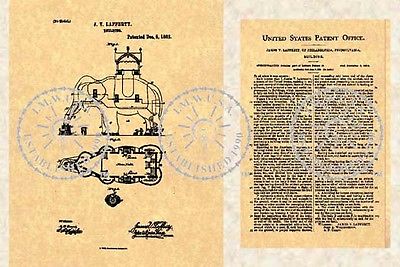

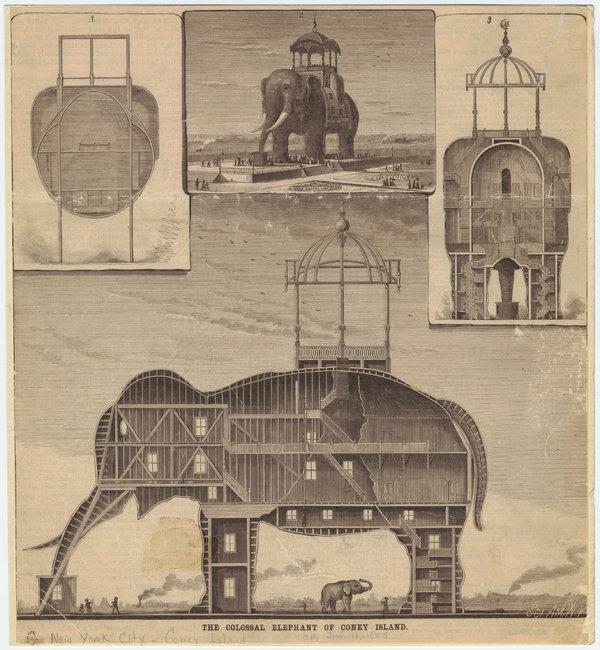

James Vincent de Paul Lafferty, Jr. (1856-1898) was an Irish-American inventor from Philadelphia. On December 5, 1882 he received he received Patent Number 268503 to protect his original invention, as well as any animal-shaped building.

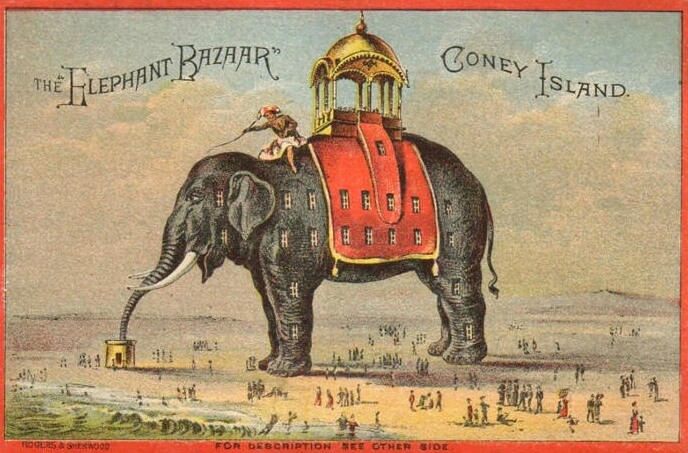

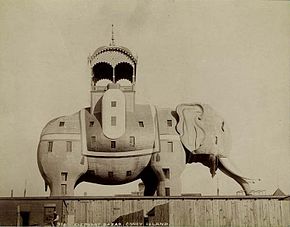

He built two other large elephants. One was the Elephant Hotel built in 1885 above Surf Avenue and West 12th Street, Coney Island. During its lifespan, the thirty-one room building acted as a hotel, concert hall, and amusement bazaar, and brothel.

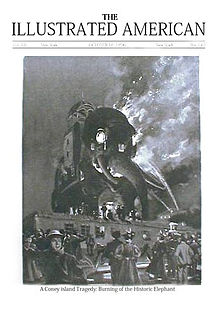

When the elephant caught fire on September 27, 1896, it had not been used for several years.

The third big elephant was the “Light of Asia” or “Old Dumbo” built in Cape May, New Jersey, in 1884.

It was torn down before the turn of the century.

When I took this little post to my friend, he was sitting in his toile-upholstered Lazy Boy recliner listening to Mandolin Orange. “Good sound!” he said. He took the draft post and handed me two postcards he had gotten a few days ago from our friend Gabby, who was at the time of sending in Paris.

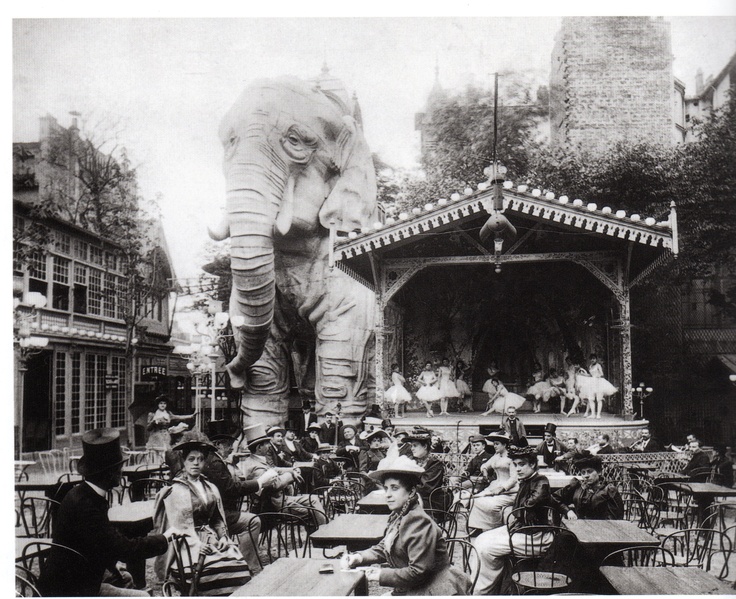

Gabby explained on the card: “It’s the Jardin de Paris Elephant. Erected in a garden near the Moulin Rouge in 1889 and torn down in 1906. Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller bought the giant stucco elephant they had seen at the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1889. At the Moulin Rouge, it was part opium den part brothel.”

Gabby explained on the card: “It’s the Jardin de Paris Elephant. Erected in a garden near the Moulin Rouge in 1889 and torn down in 1906. Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller bought the giant stucco elephant they had seen at the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1889. At the Moulin Rouge, it was part opium den part brothel.”

Good knowledge! Just like Gabby to try to show us up.

Anyway, what does my friend think of my little lesson about Shep and Lafferty’s elephants?