In principio erat verbum

In the beginning, there was the word. The written word was valued on old weird Telegraph. Sometimes in mimeographed leaflets, sometimes in bright and intricate posters, sometimes in newsprint – but everywhere valued. I look here at underground newspapers and leaflets, underground comics of the late 60s and early 70s, and the post-golden age literature of Telegraph.

In the beginning, there was the word. The written word was valued on old weird Telegraph. Sometimes in mimeographed leaflets, sometimes in bright and intricate posters, sometimes in newsprint – but everywhere valued. I look here at underground newspapers and leaflets, underground comics of the late 60s and early 70s, and the post-golden age literature of Telegraph.

The Word Underground in the 60s and 70s

We have visited the bookstores of the era, but a few notches down on the written-word-food-chain were underground newspapers.

Telegraph Avenue had seen counter-dominant-narrative written word before 1965, and it is worth looking at. If you are interested. It was all pretty serious stuff. I don’t include here for the sake of brevity. But you can see it.

Telegraph Avenue had seen counter-dominant-narrative written word before 1965, and it is worth looking at. If you are interested. It was all pretty serious stuff. I don’t include here for the sake of brevity. But you can see it.

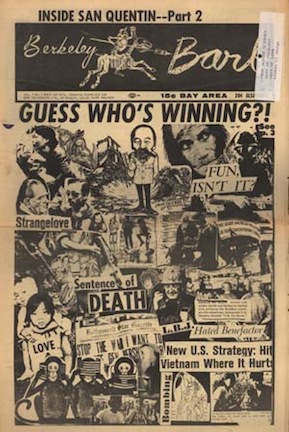

And then came the Barb.

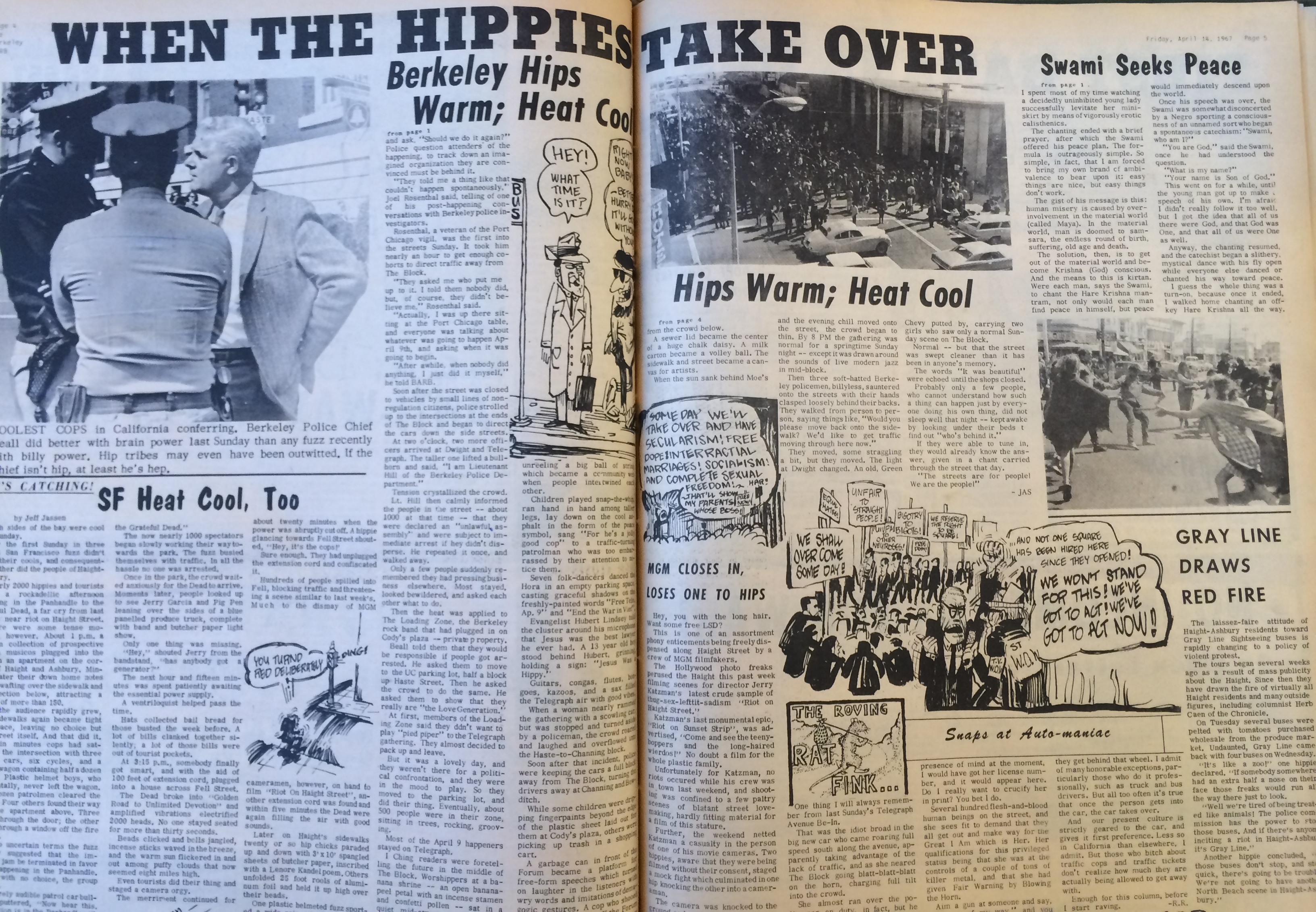

One of the earliest underground newspapers in the United States was our very own Berkeley Barb, which came into being in 1965, birthed by Max Scherr and his counterculture staff. The Los Angeles Free Press had been around for a year at that time, the East Village Other started the same year, and it would be another year before San Francisco saw The Oracle. Pioneers!

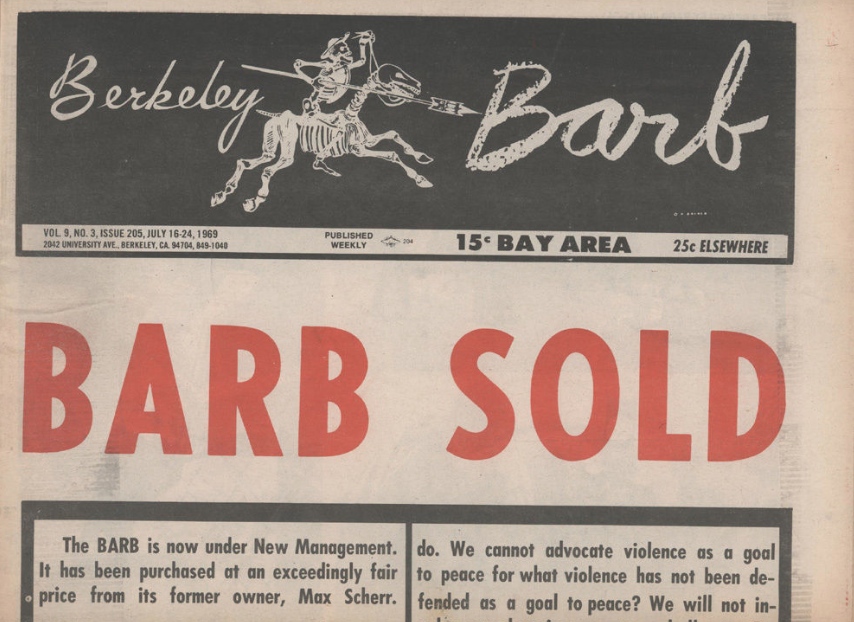

In 1969, things started getting weirder. There was talk of the Barb being sold, and for a time it looked like Anthropology Professor Allan Coult had bought it.

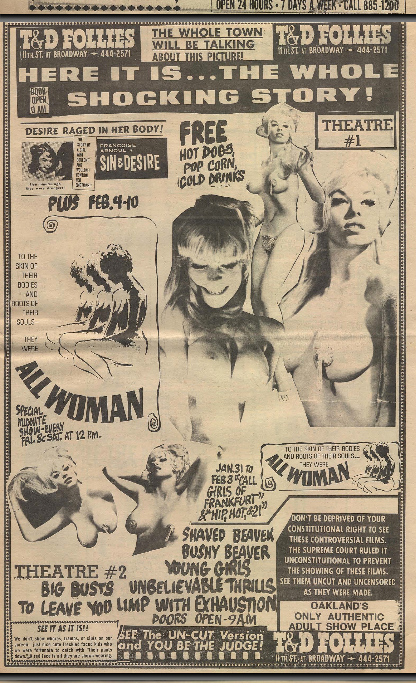

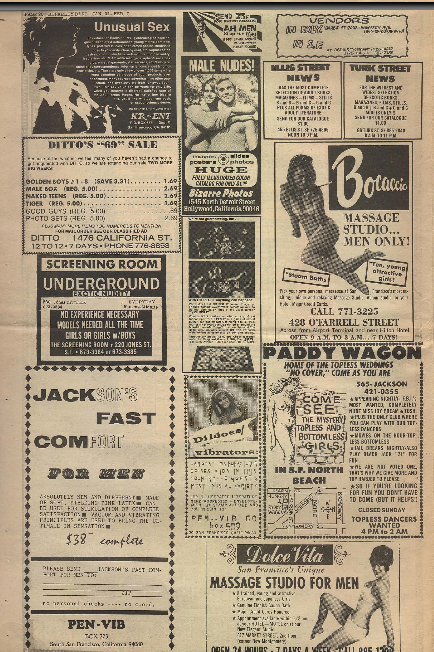

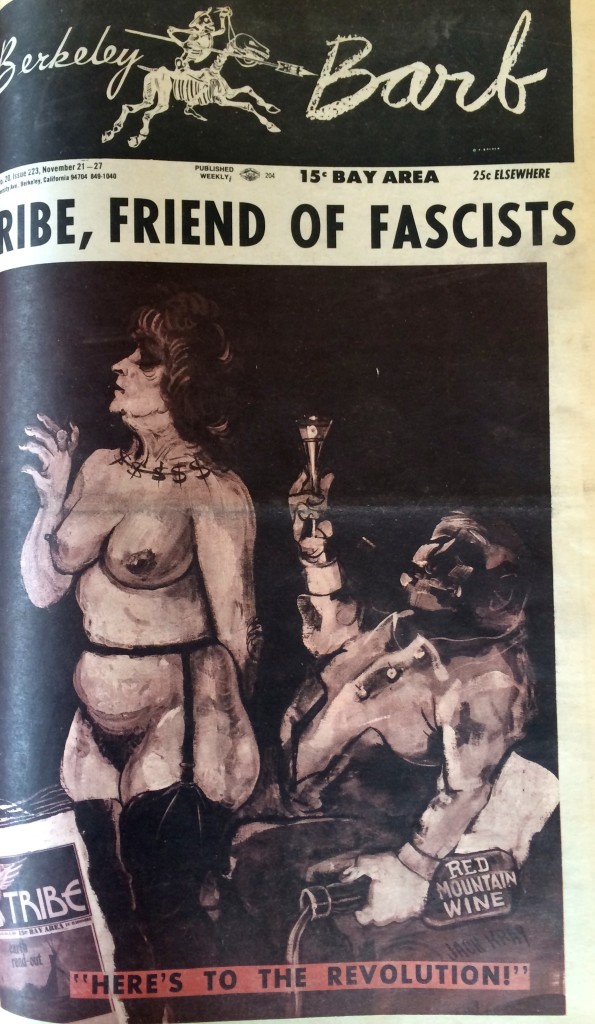

In 1969, things started getting weirder. There was talk of the Barb being sold, and for a time it looked like Anthropology Professor Allan Coult had bought it.  The deal fell through. Shortly after, The Barb staff went on strike and started the Berkeley Tribe. There were economic issues, to be sure, but most who went on strike spoke of their dislike of the direction that The Barb was taking with advertisers. The sexual revolution, the rise of feminism, and the old-fashioned sleazy sex industry did not play well together. Max saw the money to be made on sex ads and couldn’t resist. Pages looked like this:

The deal fell through. Shortly after, The Barb staff went on strike and started the Berkeley Tribe. There were economic issues, to be sure, but most who went on strike spoke of their dislike of the direction that The Barb was taking with advertisers. The sexual revolution, the rise of feminism, and the old-fashioned sleazy sex industry did not play well together. Max saw the money to be made on sex ads and couldn’t resist. Pages looked like this:

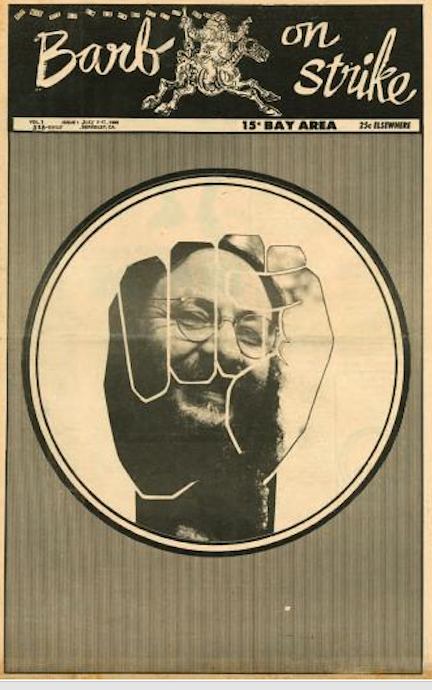

It is hard, probably impossible, to sort out the reasons for the strike and split. Whatever the reasons, pretty much the whole staff went on strike in 1969. Here is their first issue announcing the strike:

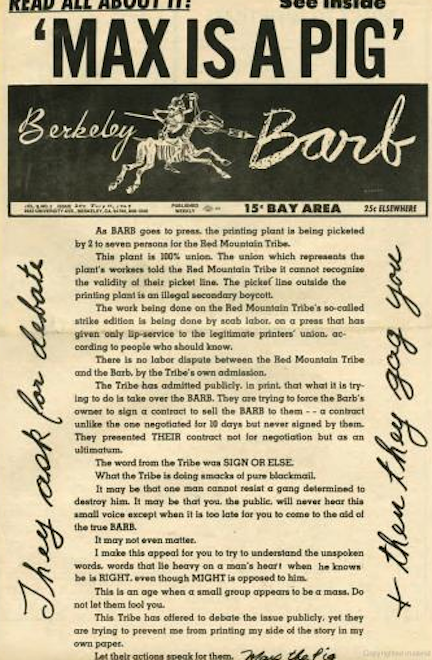

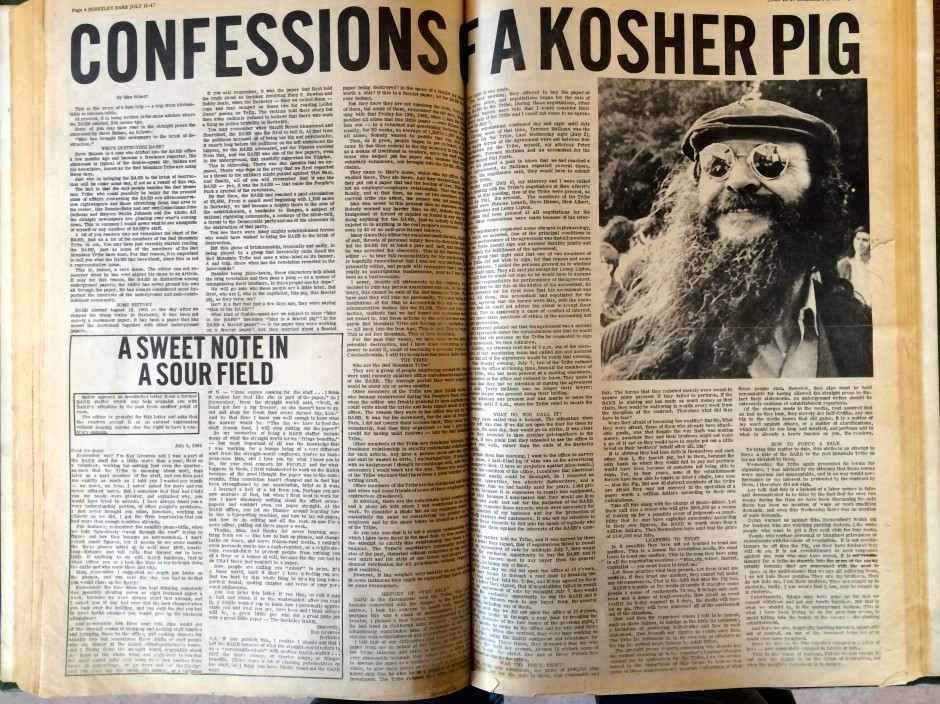

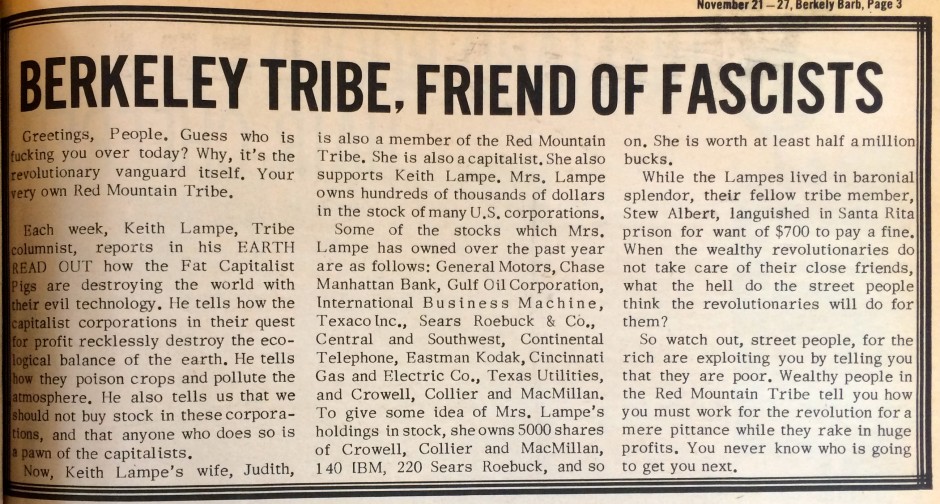

It is hard, probably impossible, to sort out the reasons for the strike and split. Whatever the reasons, pretty much the whole staff went on strike in 1969. Here is their first issue announcing the strike:  Max outdid them, mocking himself in the Barb and then pointing out a few of the contradictions in the strikers’ position.

Max outdid them, mocking himself in the Barb and then pointing out a few of the contradictions in the strikers’ position.

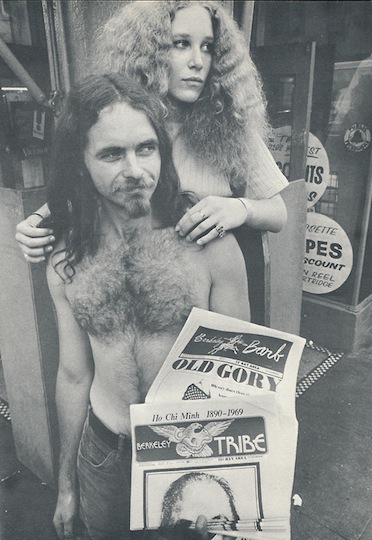

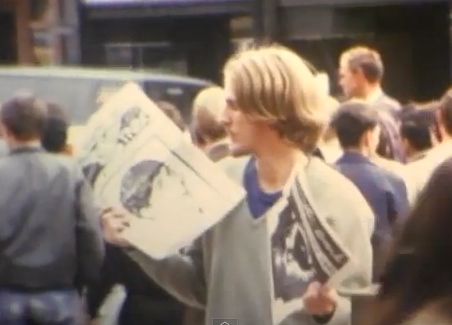

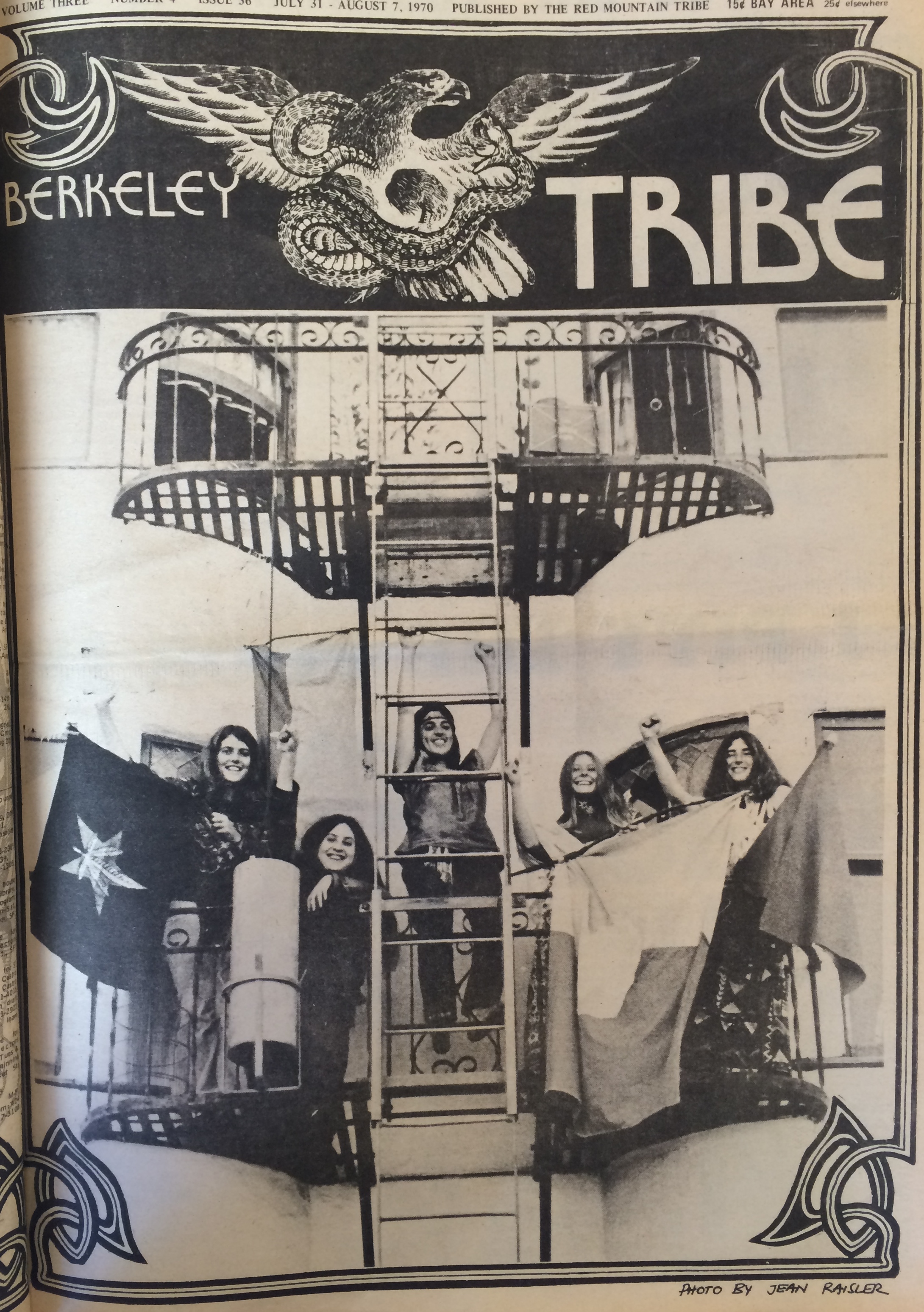

The strikers then started putting out the Berkeley Tribe. So there were two underground papers, The Barb and The Tribe.

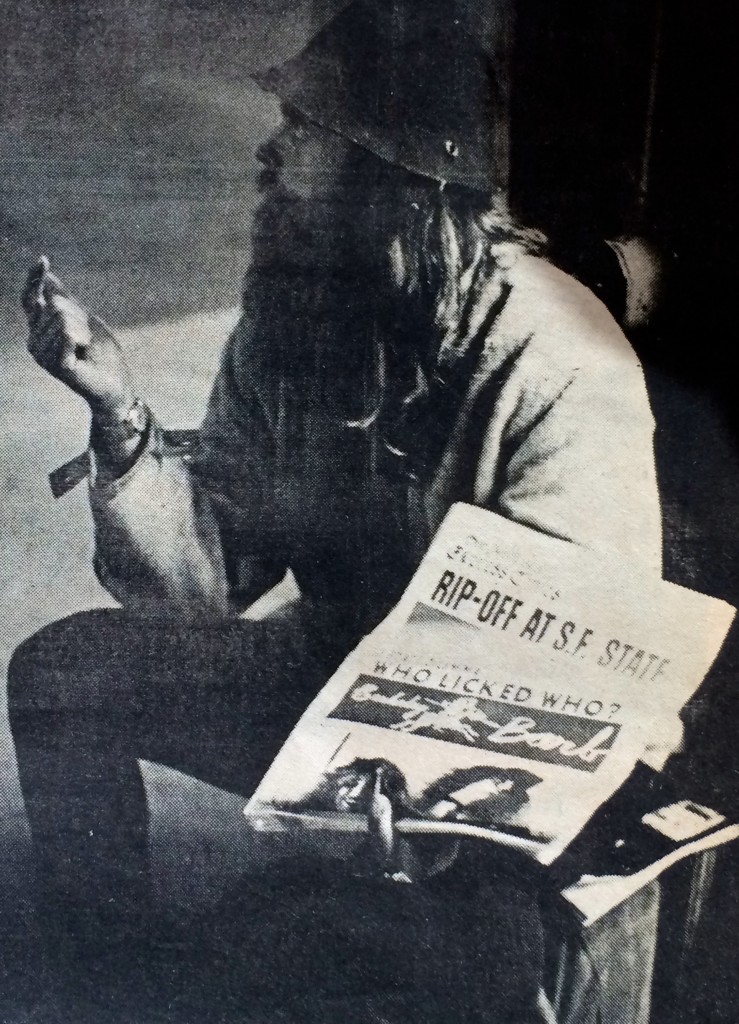

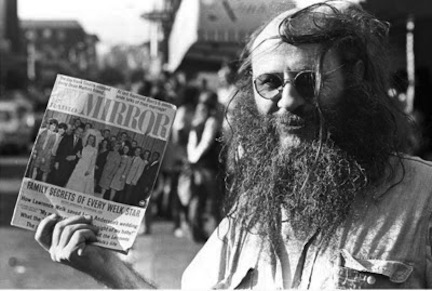

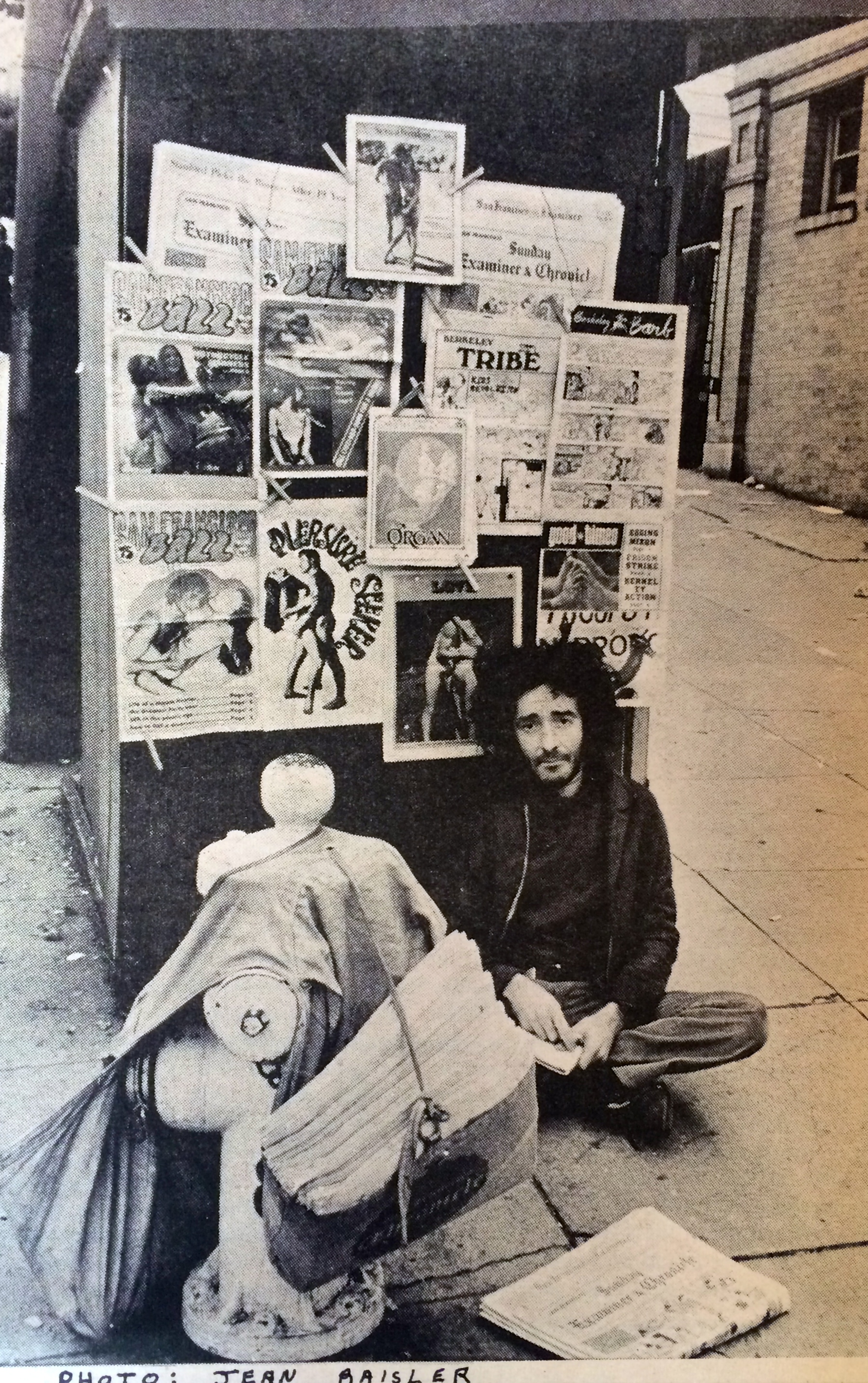

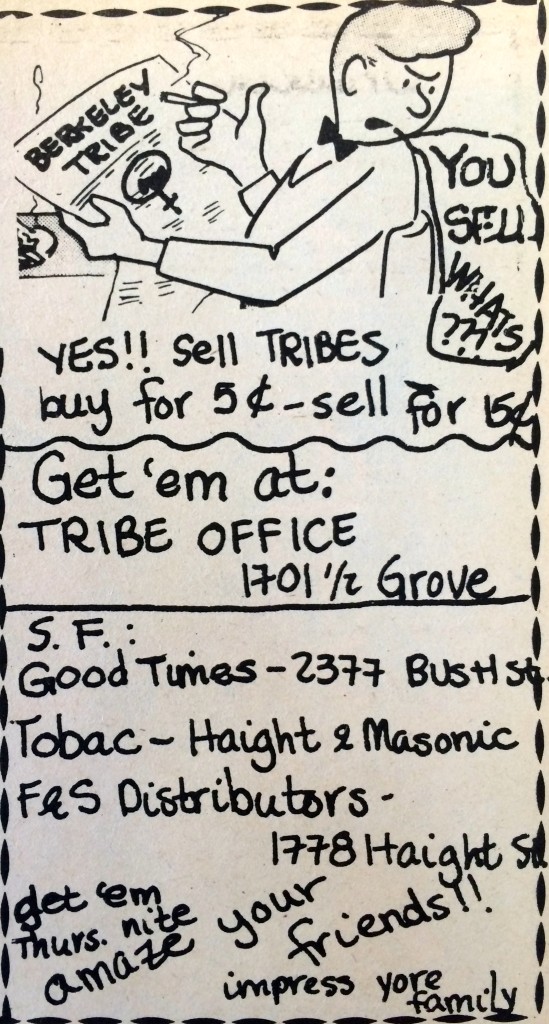

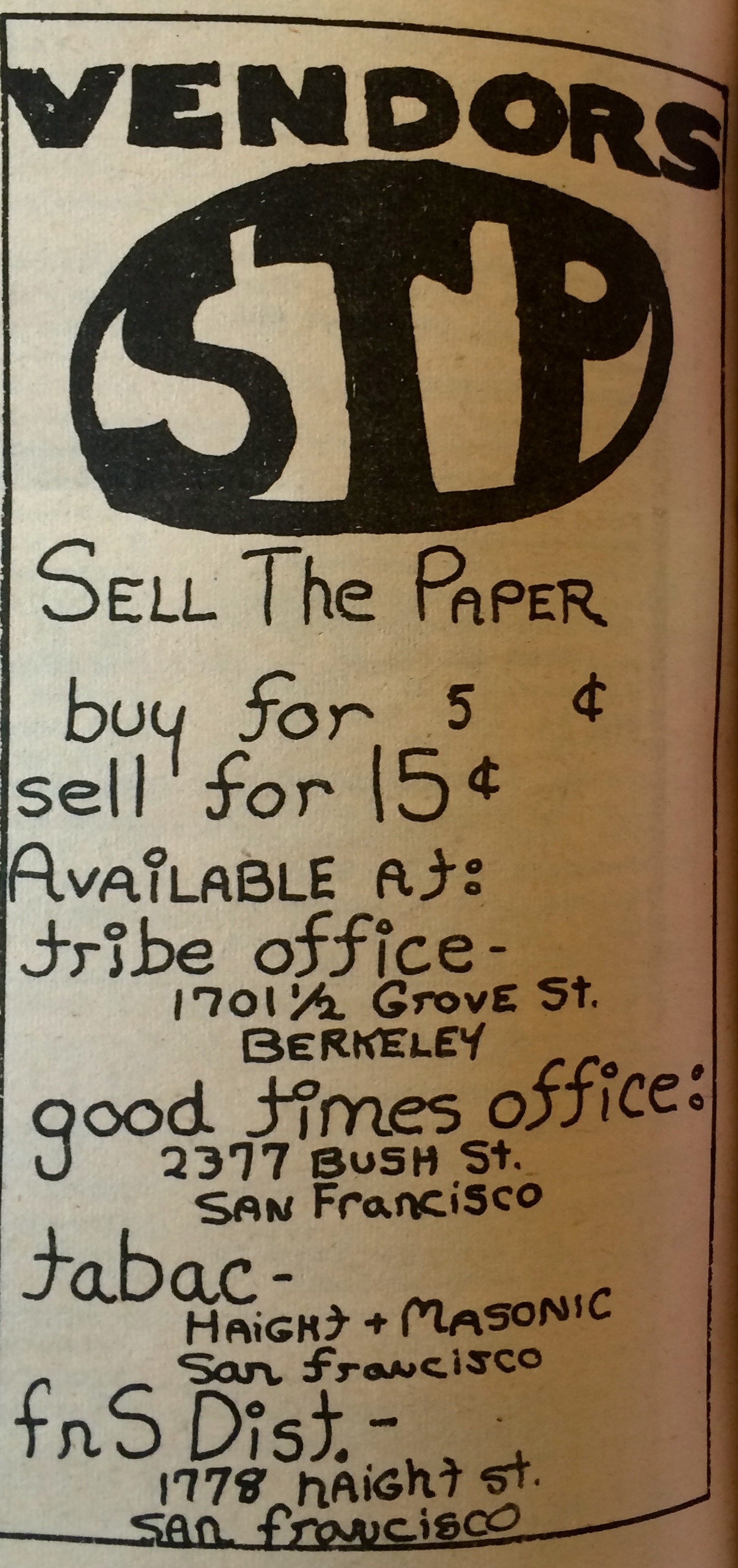

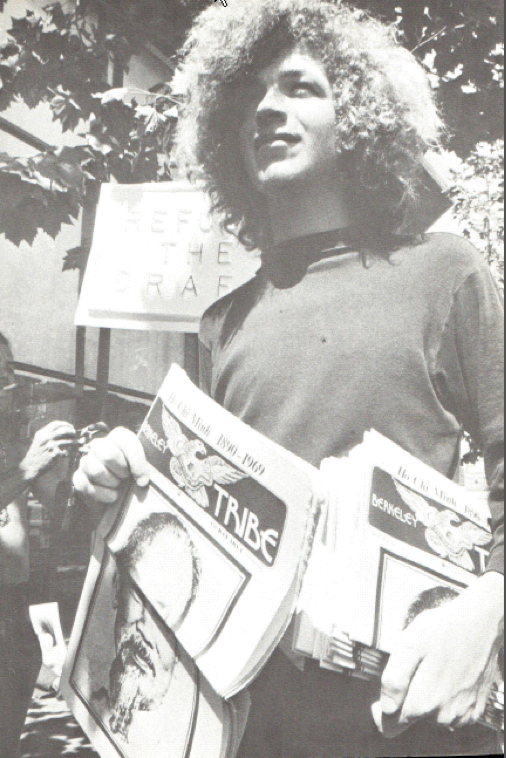

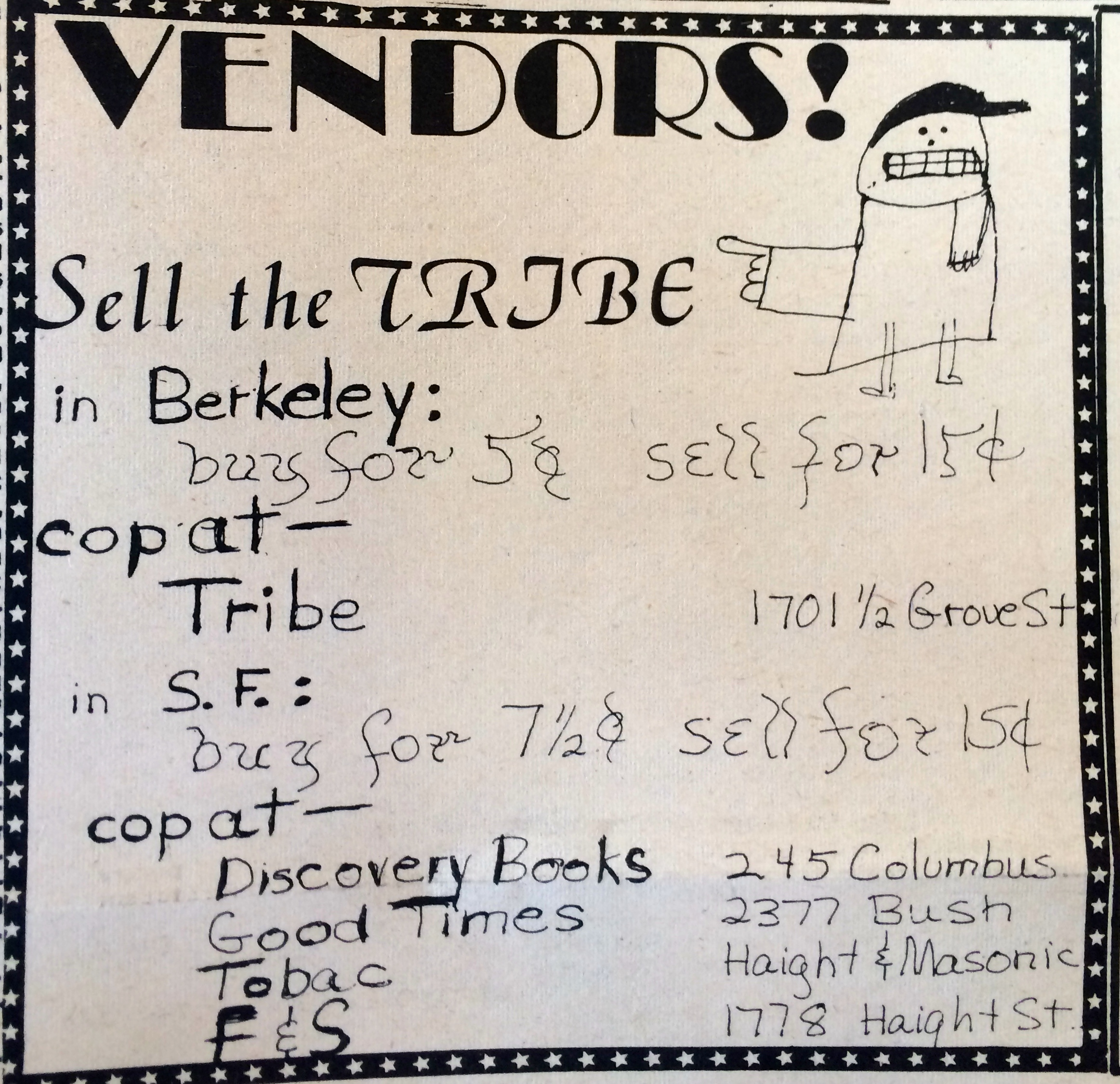

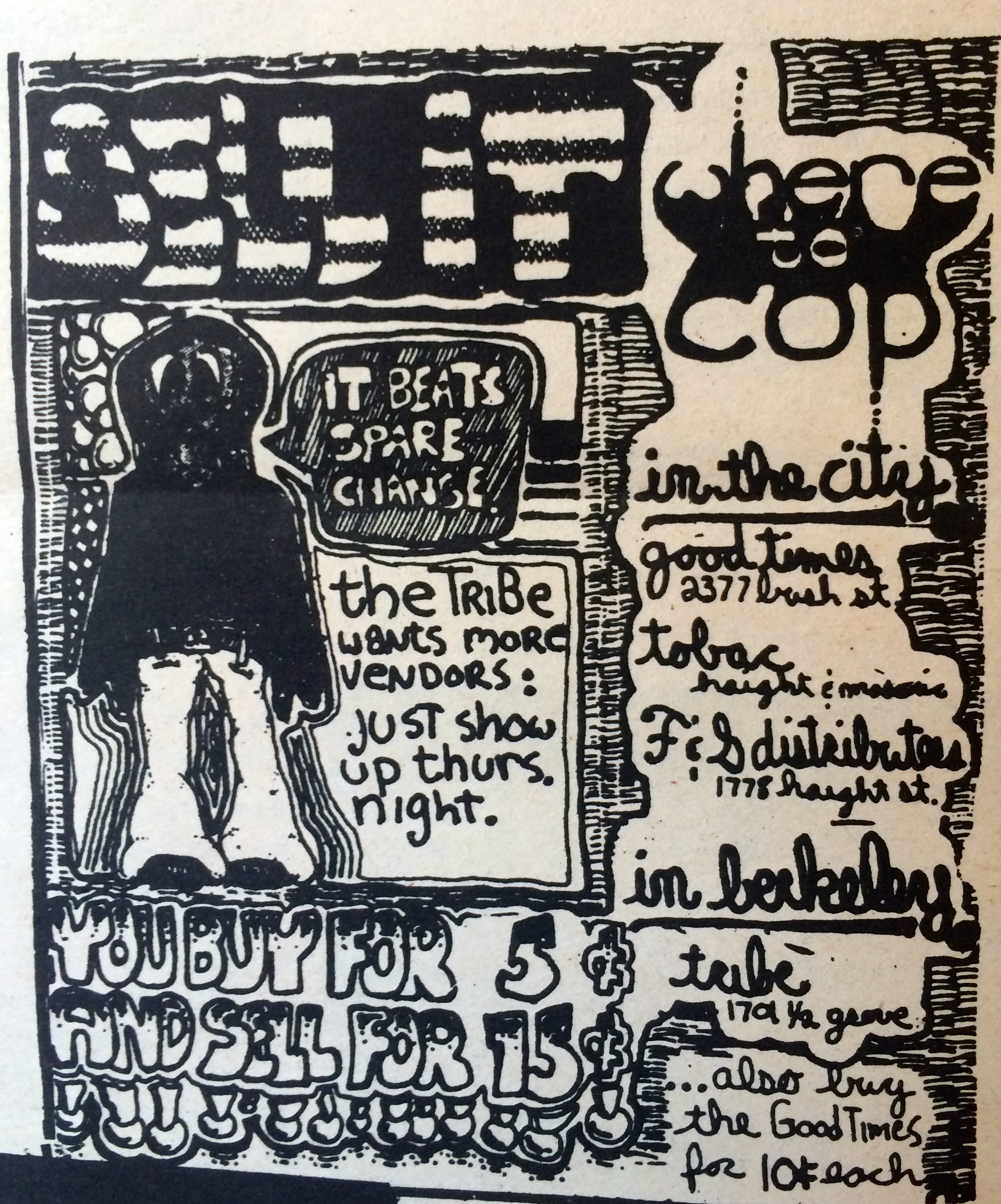

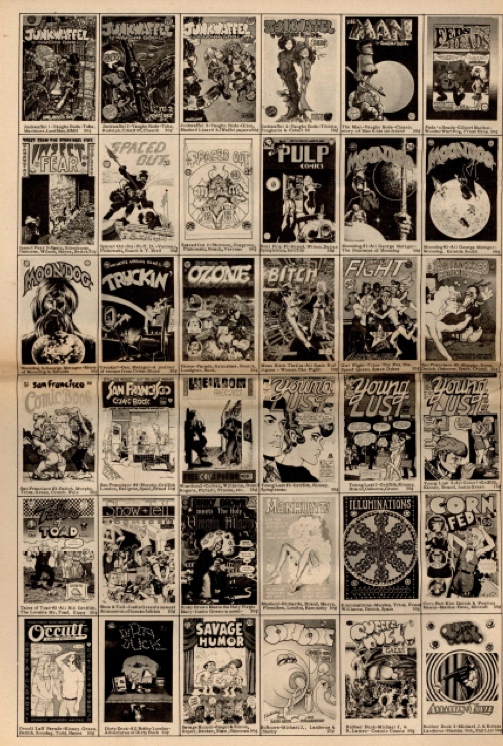

Like the Barb, the Tribe relied on street vendors.

The Tribe soon surpassed The Barb.

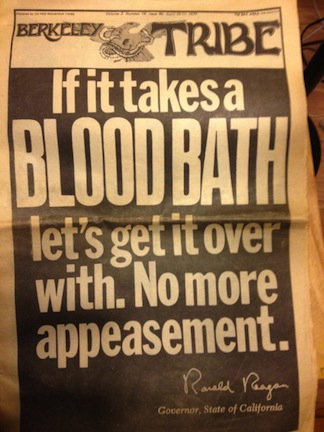

Max lashed out in the beginning.

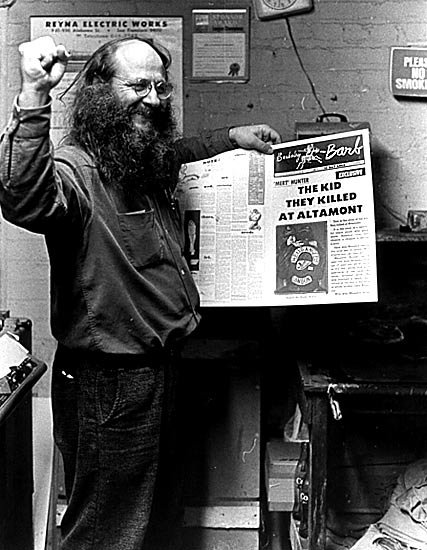

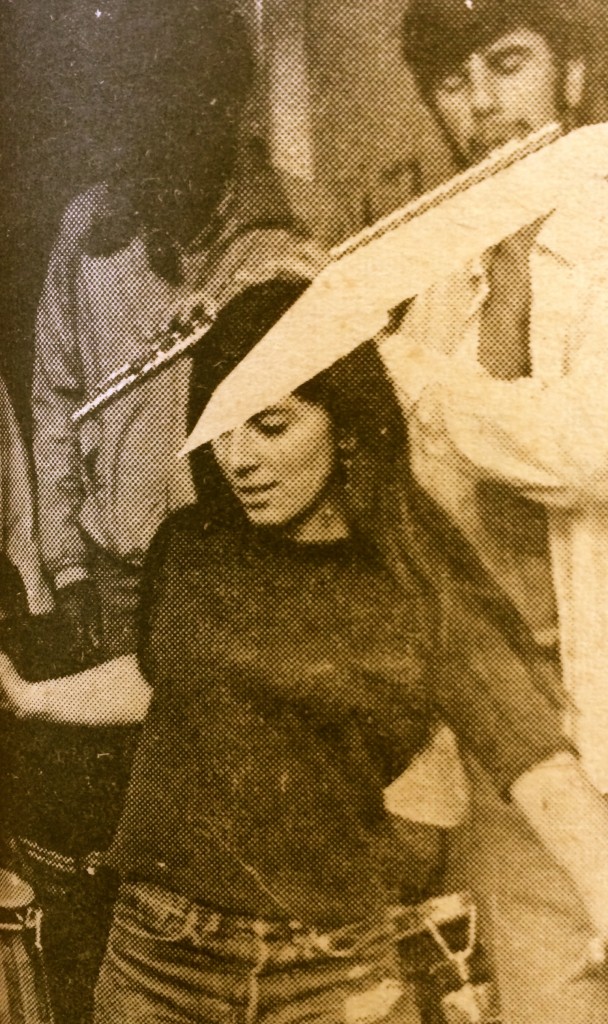

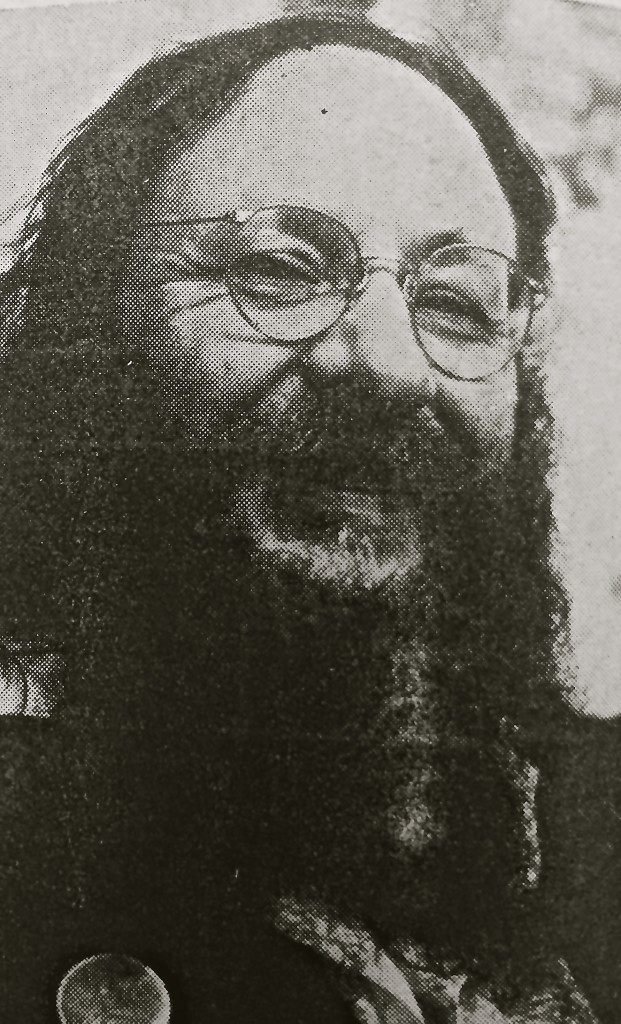

At times he rediscovered his sense of humor, as demonstrated in this photo from the Tribe:

Within less than a year two things happened. The Tribe got into a financial jam.

And Max had a heart attack, leading to kind words from the Tribe:

And Max had a heart attack, leading to kind words from the Tribe:  Max got better. The Tribe‘s finances improved slightly, and before long the Tribe’s circulation surpassed that of the Barb. The Tribe needed to move from their Ashby house. They asked for help.

Max got better. The Tribe‘s finances improved slightly, and before long the Tribe’s circulation surpassed that of the Barb. The Tribe needed to move from their Ashby house. They asked for help.

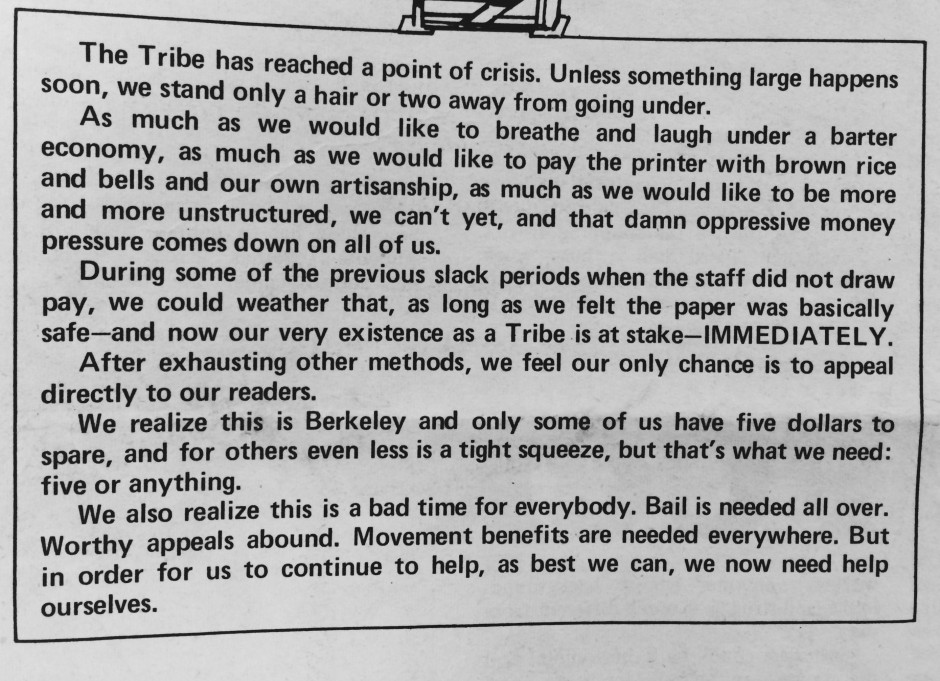

In 1971, two years into the paper’s production, they were in trouble again financially:

In 1971, two years into the paper’s production, they were in trouble again financially:

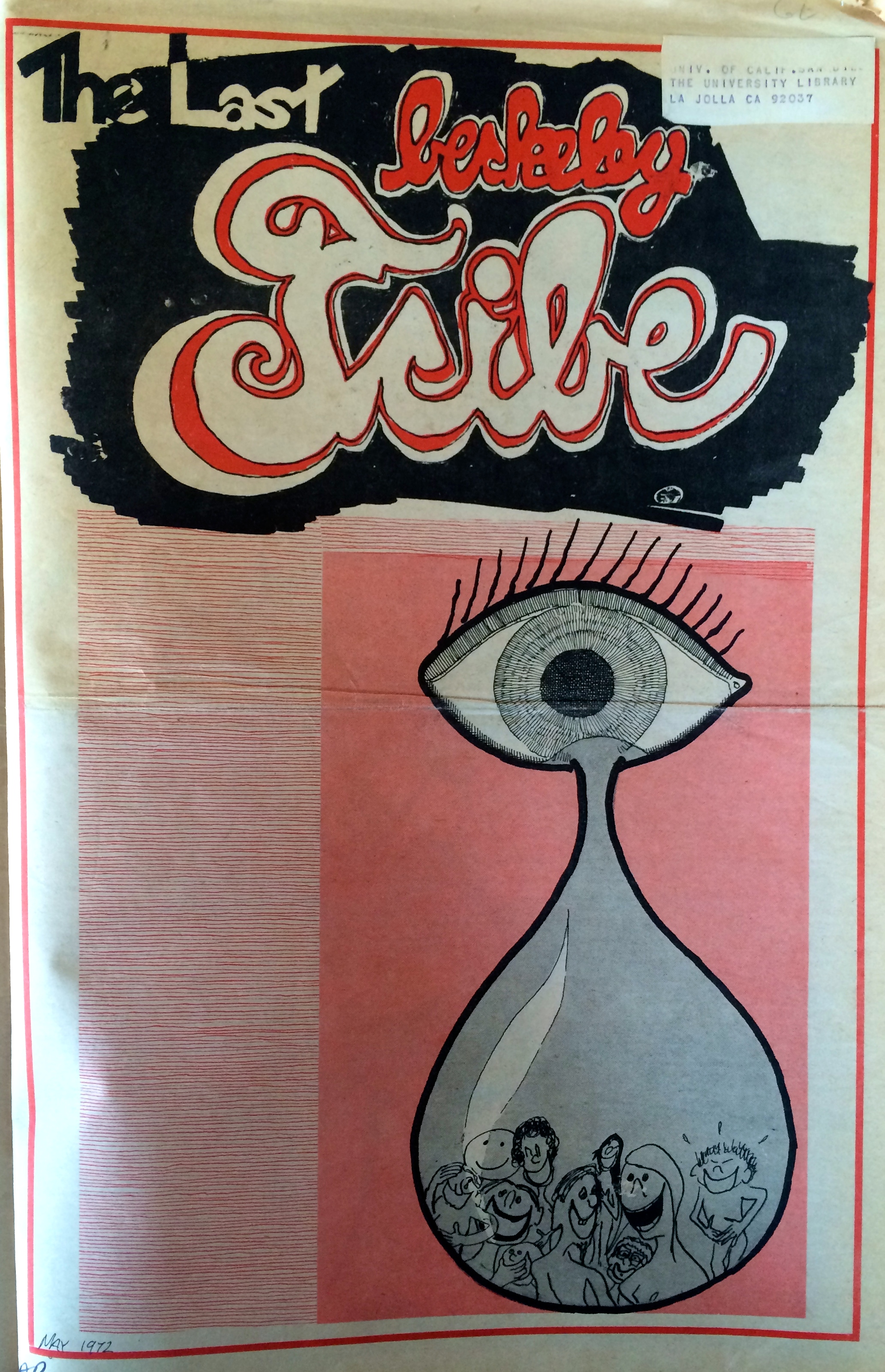

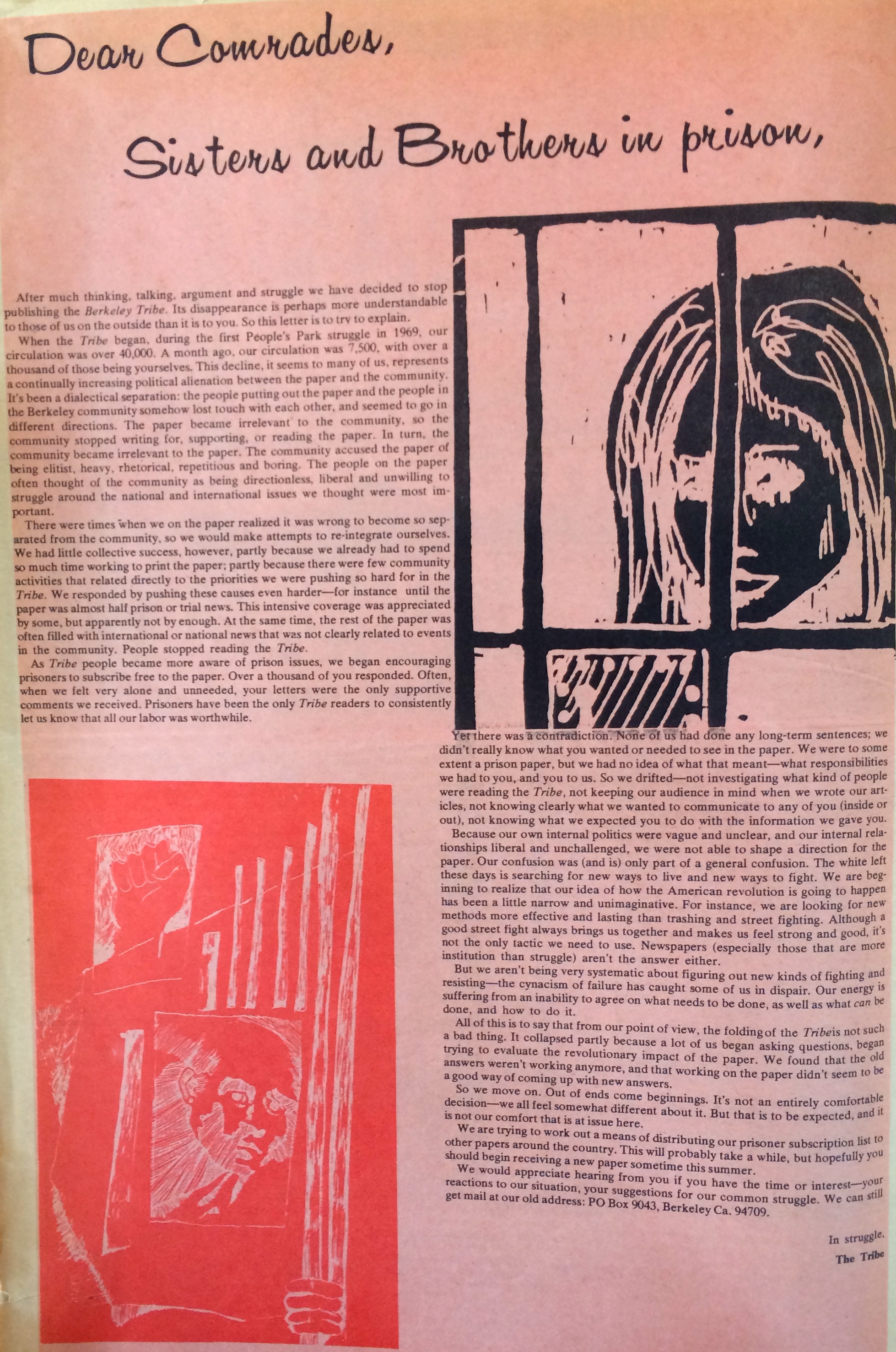

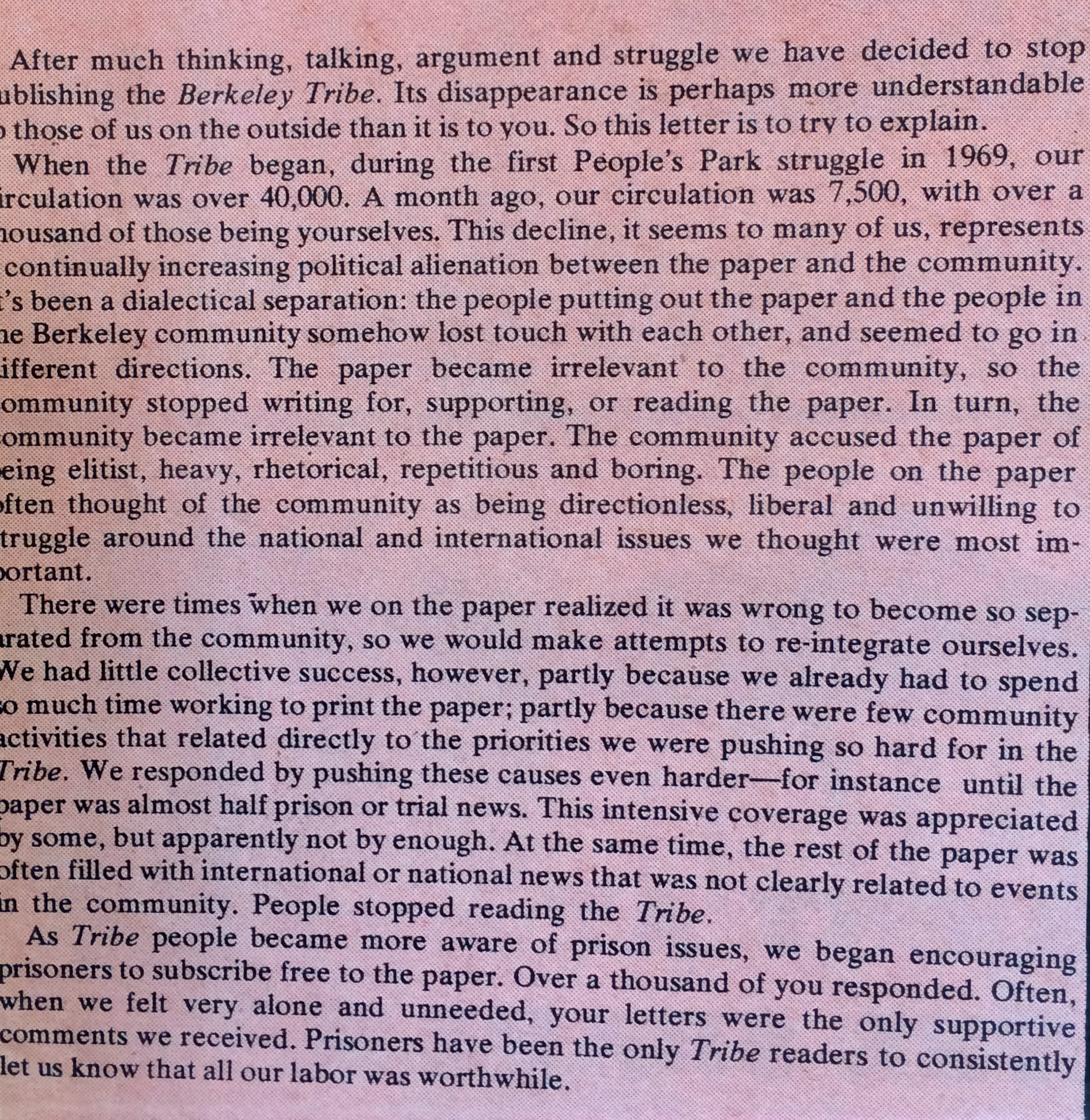

In 1972, the Tribe dissolved into hard-left and radical-feminist infighting and revenue shortfalls.

It folded. You will see from the above that the staff saw their failure as one of not grasping what prisoners who got the paper for free wanted to read. The Barb survived the 1970s, spinning off its sex section into the Spectator Magazine in 1978. The Barb started tanking. In 1980 we got President Reagan and lost the Barb.

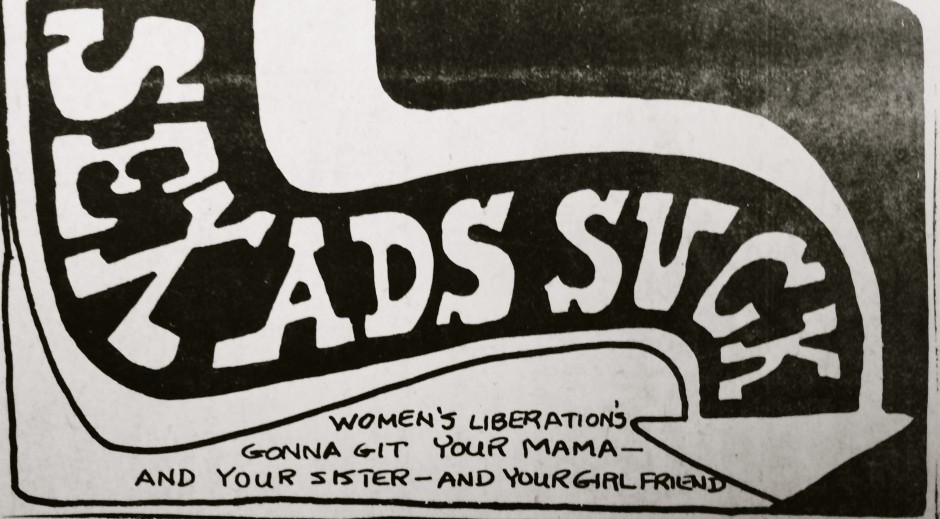

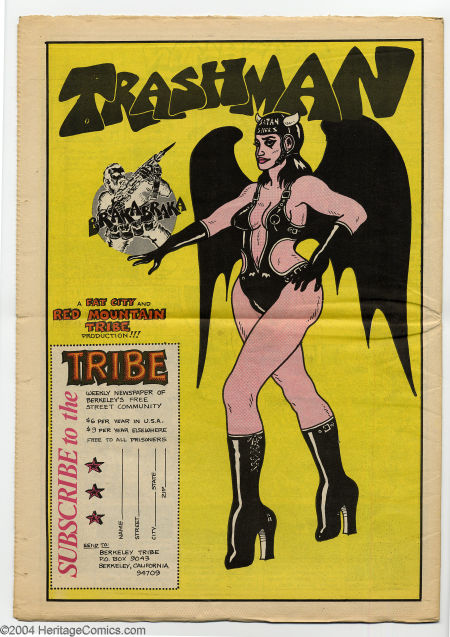

The claim that a large reason for the Barb staff strike was the sexual sleaze that Max was willing to advertise is largely supported by the Tribe’s record on sexual material. In the first few issues of of the Tribe there ads and photographs that sell or exploit (at least to our current sensibilities) sexuality. I present most of them here.

It was from the start less sleazy than the Barb material. Even in the early Tribe issues that contained some sexual ads, they did at times call out their own advertisers:

More importantly, within a few months the sex ads were banished, or at least they were gone. The feminist politics displayed in the Tribe simply were not compatible with sleazy sex ads, revenue stream or not.

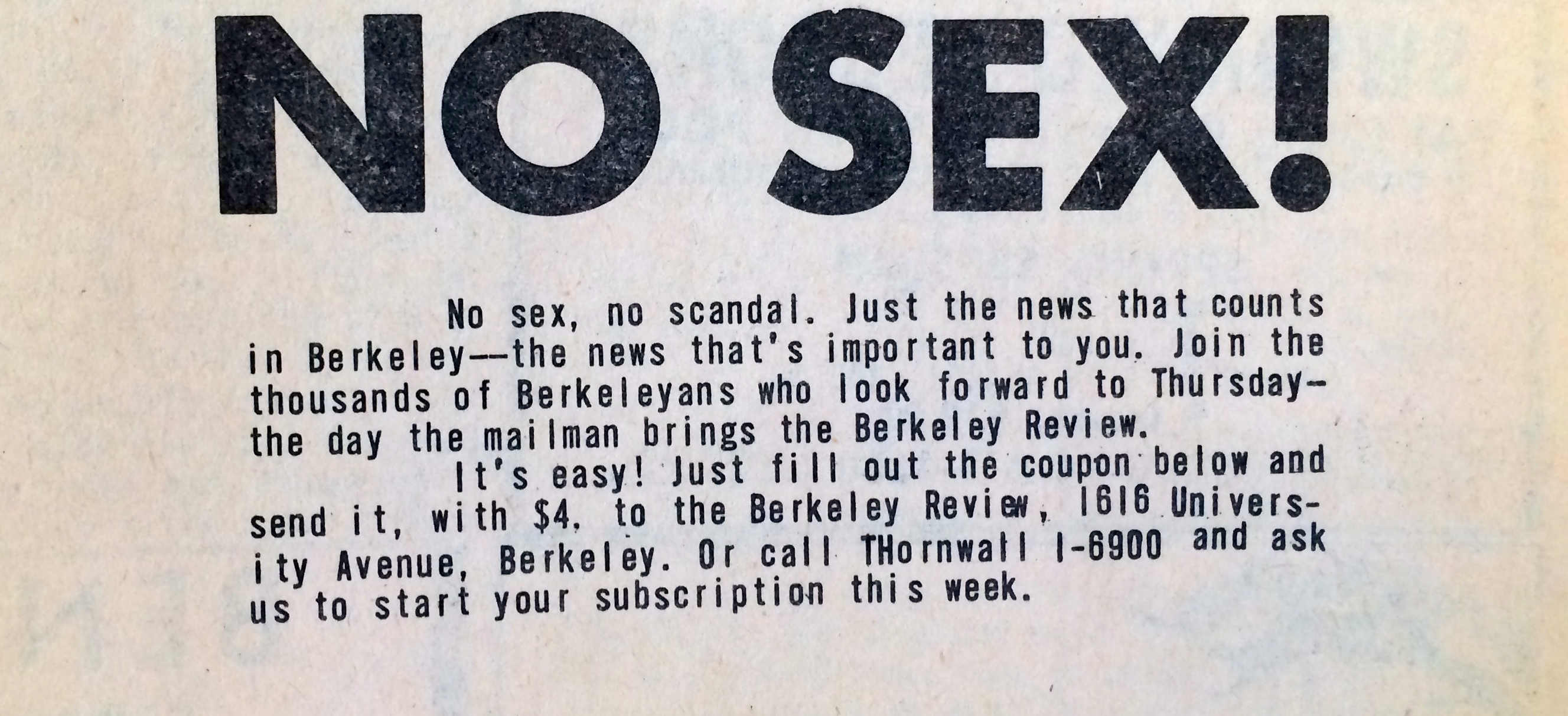

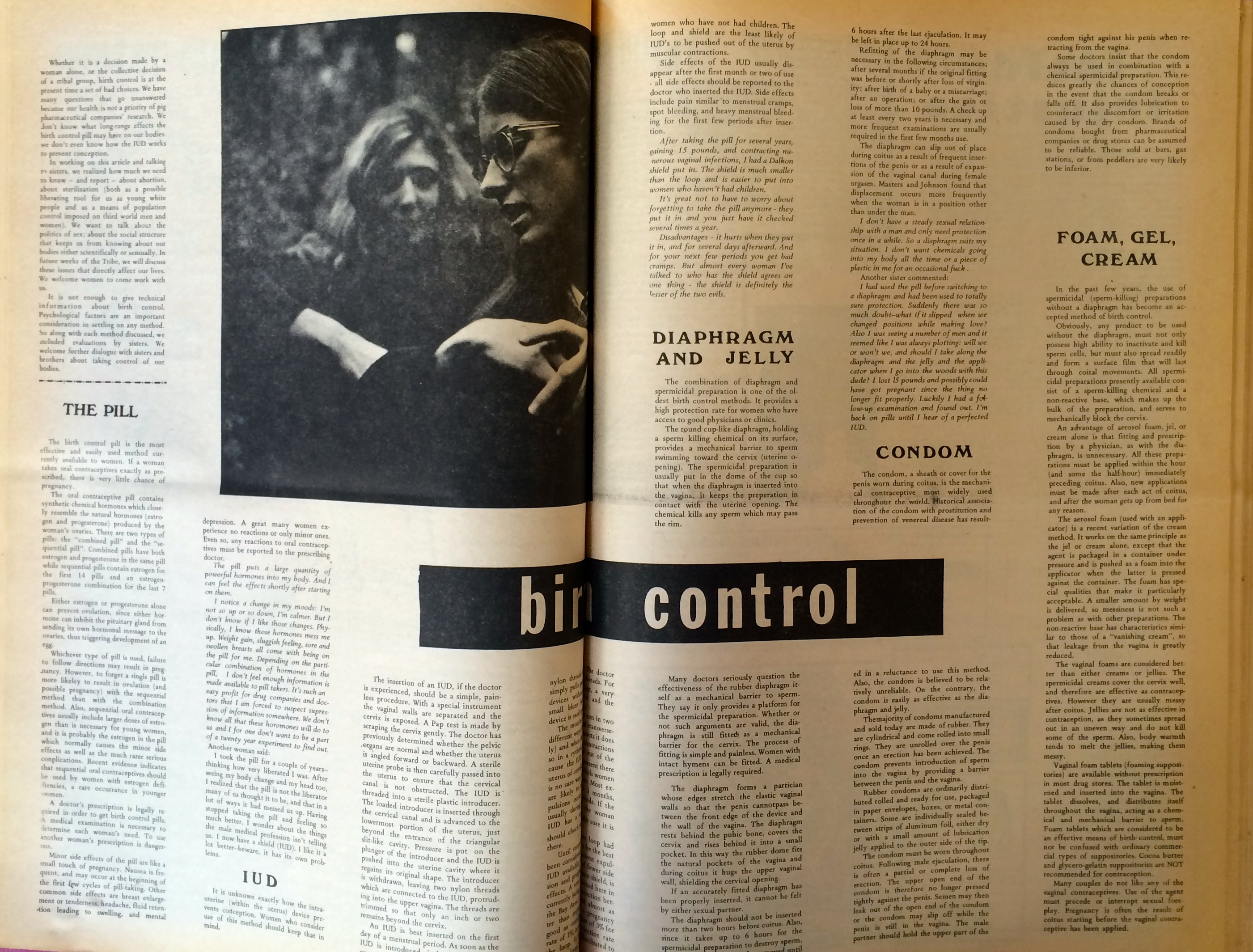

More importantly, within a few months the sex ads were banished, or at least they were gone. The feminist politics displayed in the Tribe simply were not compatible with sleazy sex ads, revenue stream or not.  This was a proclamation by the Berkeley Review in 1961. It is not clear what prompted this declaration, but it certainly stood in stark contrast to the Barb‘s sleazy ads. The Tribe did not get this prudish, and they continued to discuss sex openly, but without exploitation or sleaze, as in this centerfold discussion of birth control:

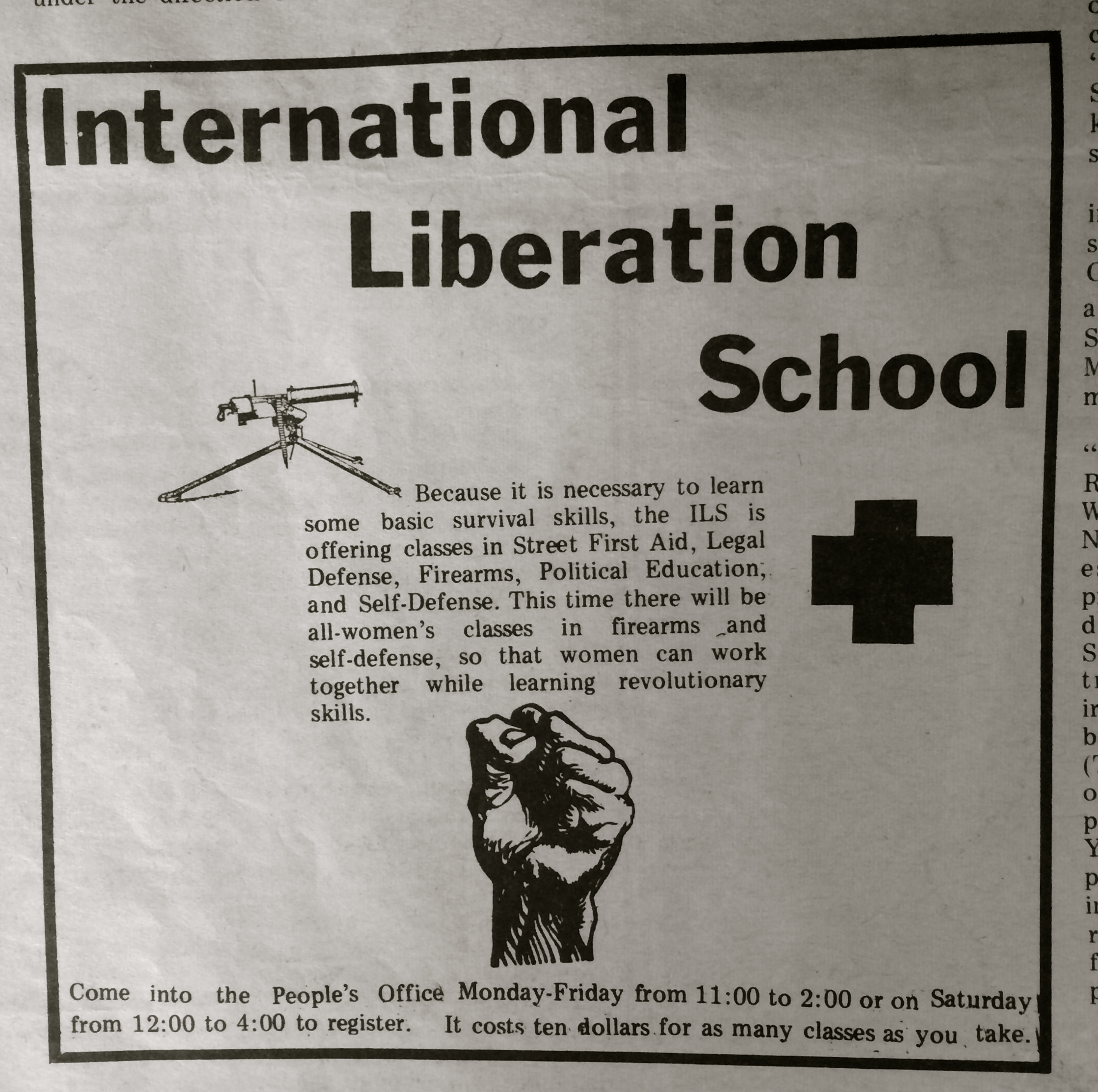

This was a proclamation by the Berkeley Review in 1961. It is not clear what prompted this declaration, but it certainly stood in stark contrast to the Barb‘s sleazy ads. The Tribe did not get this prudish, and they continued to discuss sex openly, but without exploitation or sleaze, as in this centerfold discussion of birth control:  I got ahead of myself there. Back to the formation of the Tribe. The Tribe‘s staff formed a commune, the Red Mountain Tribe, on Ashby. I don’t know where on Ashby. I want to find it. As we would say today, shit got real with Red Mountain Tribe. Working with Eldridge Cleaver of the Black Panthers, they launched the International Liberation School.

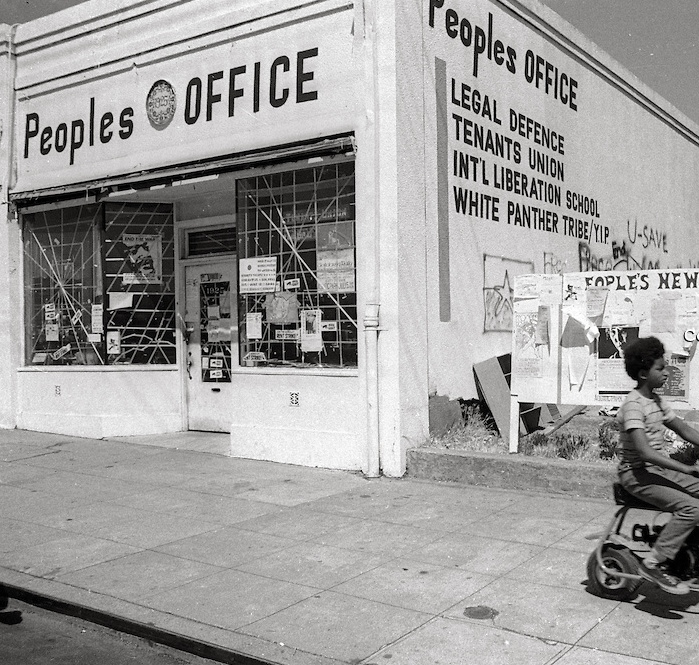

I got ahead of myself there. Back to the formation of the Tribe. The Tribe‘s staff formed a commune, the Red Mountain Tribe, on Ashby. I don’t know where on Ashby. I want to find it. As we would say today, shit got real with Red Mountain Tribe. Working with Eldridge Cleaver of the Black Panthers, they launched the International Liberation School.

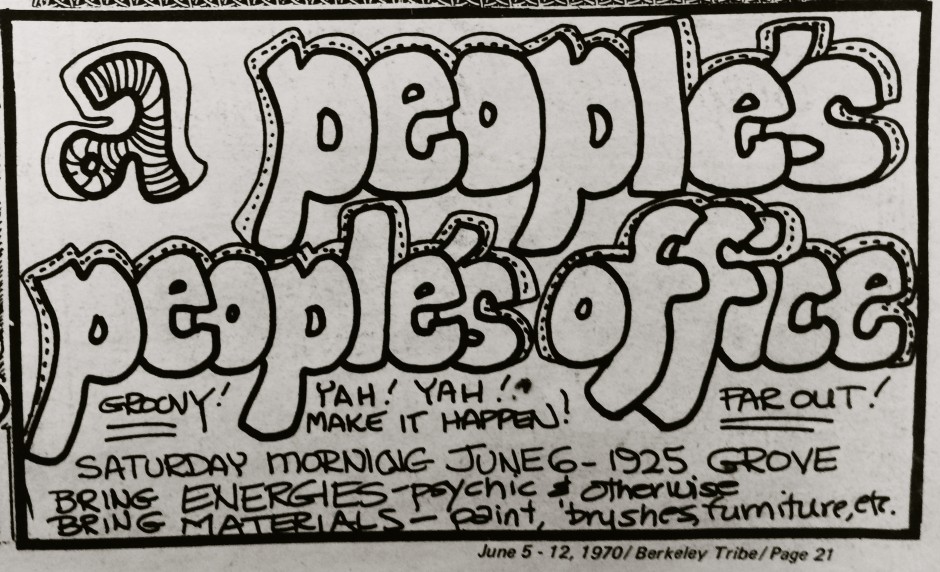

I only found this photograph recently. The address listed for The People’s Office was 1925 Grove, which is now Martin Luther King Way. KPFA’s new offices are built immediatley to the south of the building. A closed Thai restaurant is just to the north. This is what that looks like now:

I only found this photograph recently. The address listed for The People’s Office was 1925 Grove, which is now Martin Luther King Way. KPFA’s new offices are built immediatley to the south of the building. A closed Thai restaurant is just to the north. This is what that looks like now:

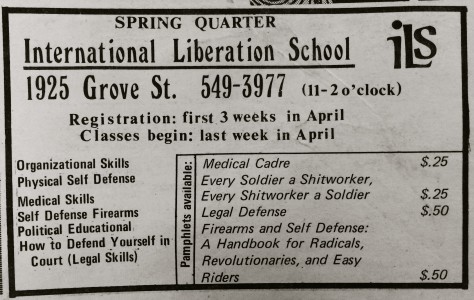

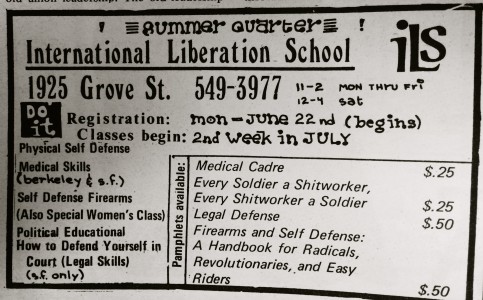

With KPFA on the south, there is a heritage present to the Liberation School’s building. And on the sidewalk in front of 1925 is this call to environmental action:  In the early 1970s they held classes.

In the early 1970s they held classes.

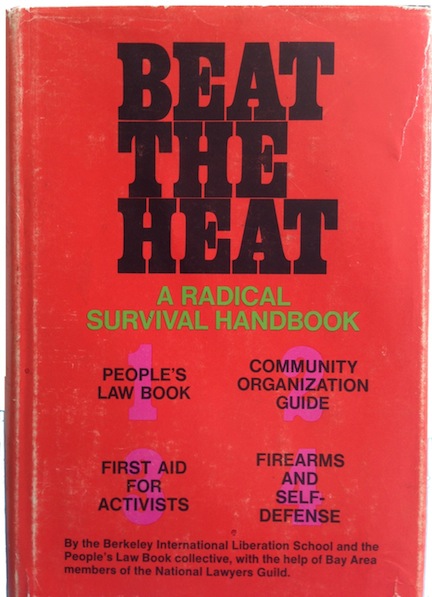

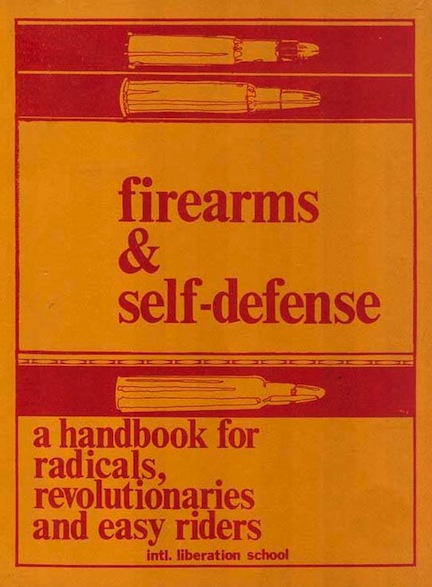

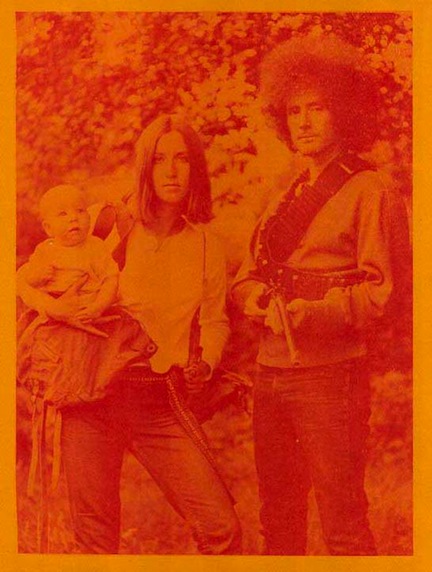

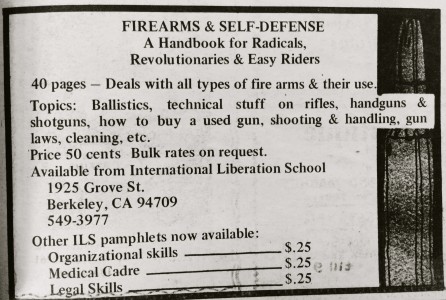

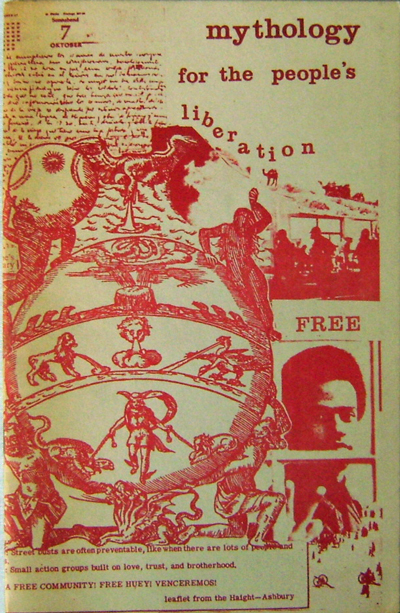

They published several books and pamphlets advocating armed struggle:

They advertised their books in their newspaper:

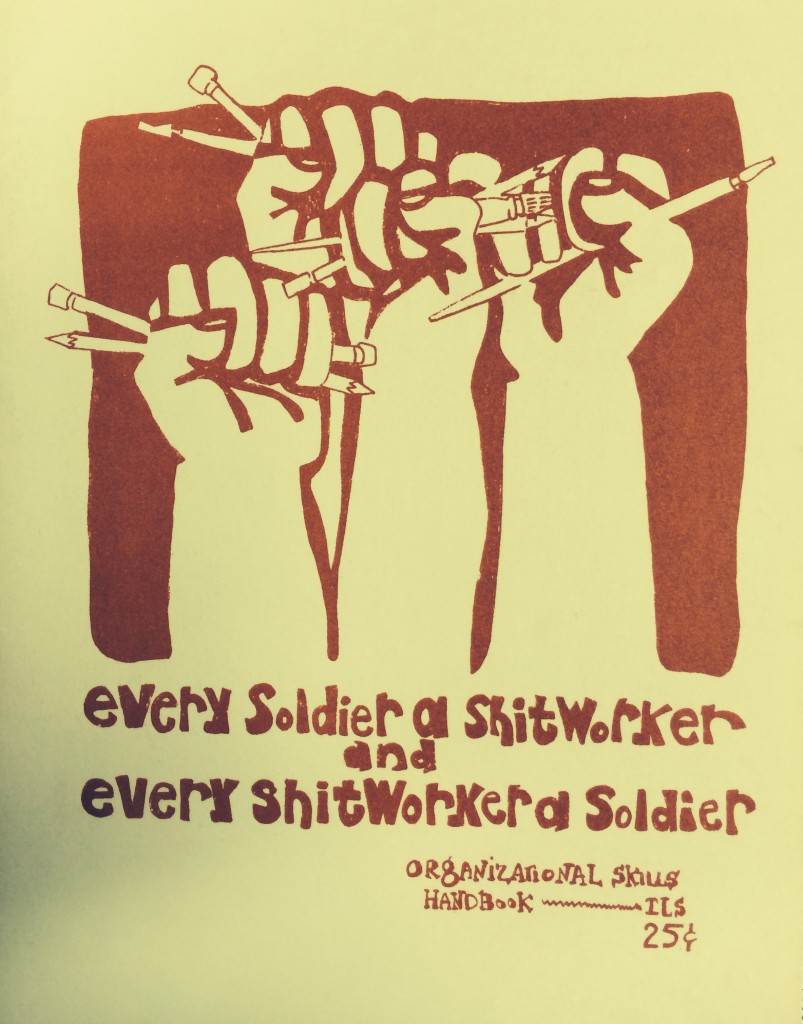

They advertised their books in their newspaper:  They issued “A Call to Arms” in which they advocated “collective, armed self-defense” and formation of a “People’s Militia.” Not all their published material was as incendiary. Some dealt with the basics of community organizing:

They issued “A Call to Arms” in which they advocated “collective, armed self-defense” and formation of a “People’s Militia.” Not all their published material was as incendiary. Some dealt with the basics of community organizing:

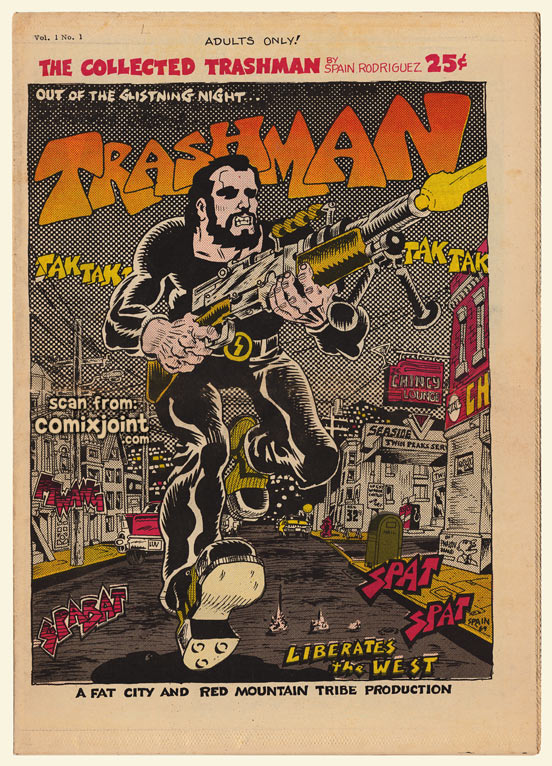

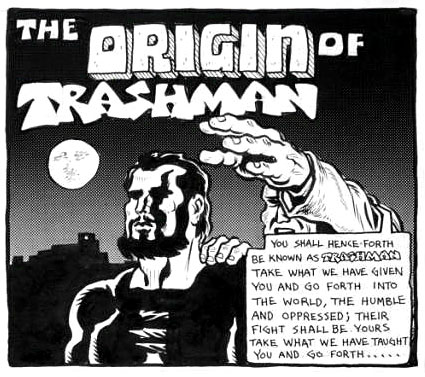

Proving perhaps that it had a sense of humor, the Red Mountain Tribe also printed several comic books.

A tad less self-conscious than the heavy stuff, wouldn’t you say?

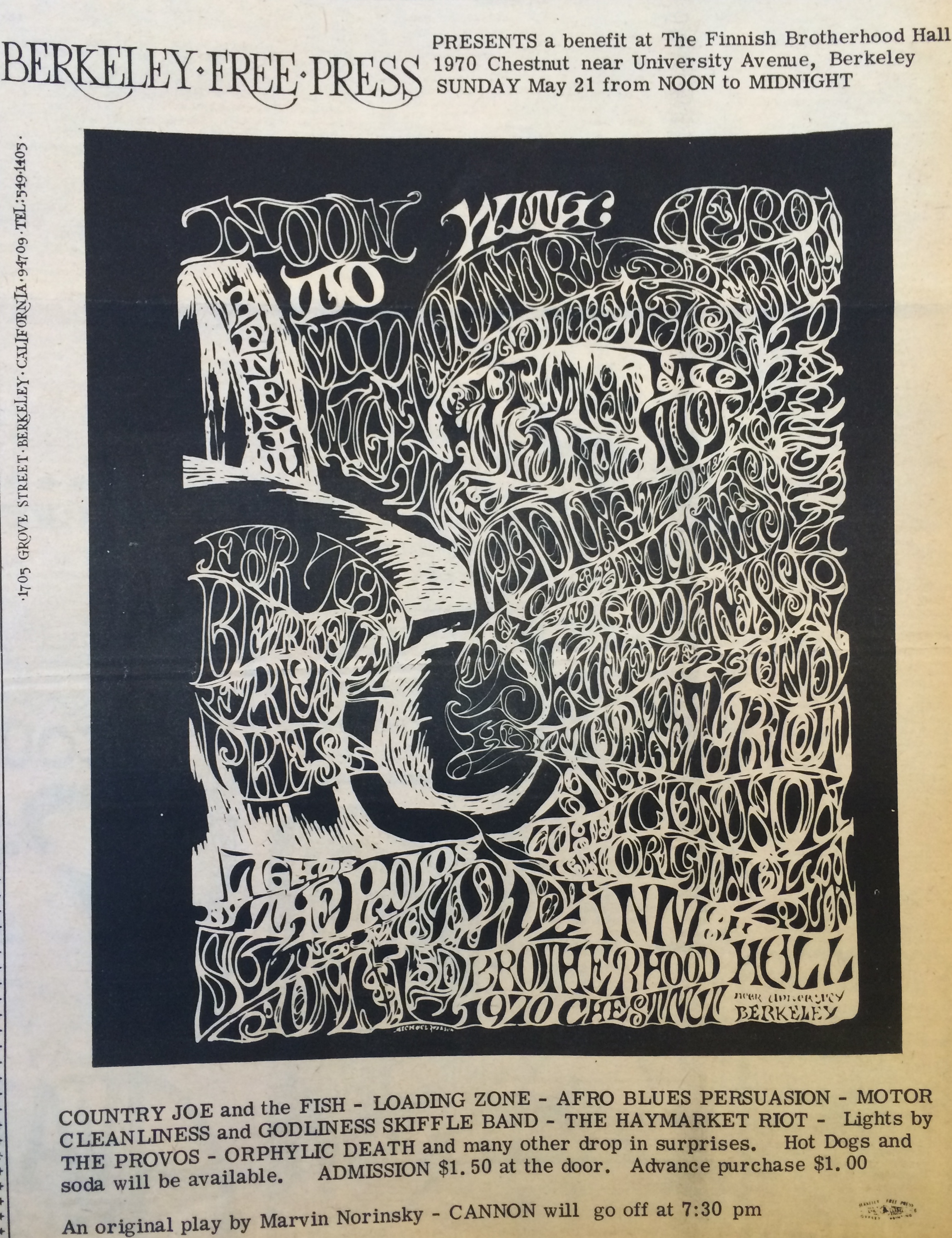

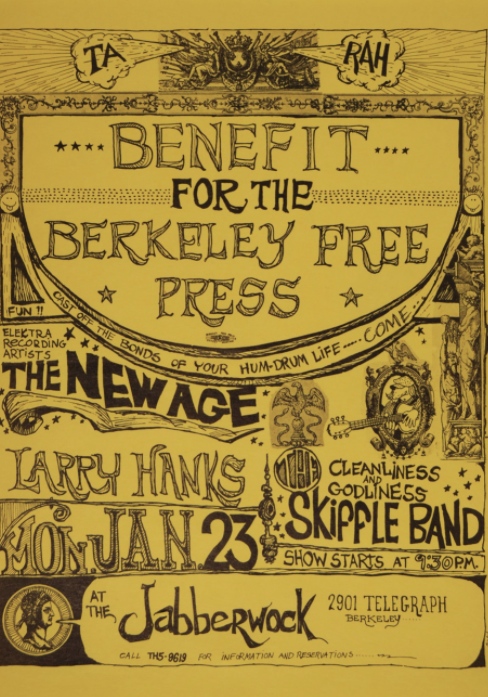

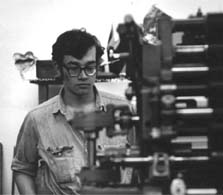

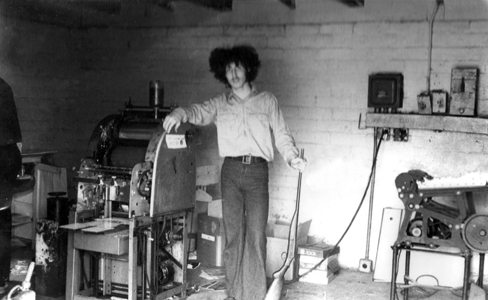

Much of this material, and many posters, were printed by the Berkeley Free Press aka Berkeley Graphic Arts.

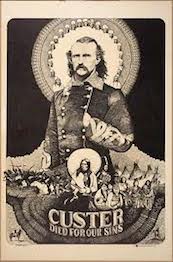

This poster was reprinted in black and white in the Berkeley Barb:

This poster was reprinted in black and white in the Berkeley Barb:

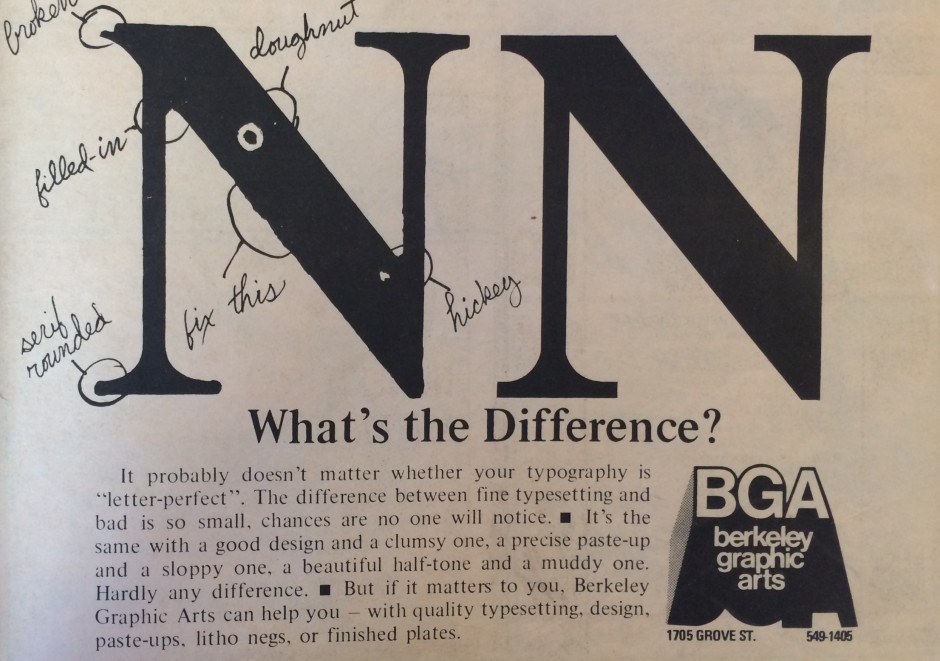

The Berkeley Free Press came into being with the Free Speech Movement. After three crazed years in service of progressive cause, it changed its name to Bereley Graphic Arts, an admittedly more bourgeois name but it at least did not sugget that prnting would be done for free. In addition to the political work that they did, they were not above the lucrative business of printing porn and they did work for the followers of Meyer Baba.

The Berkeley Free Press came into being with the Free Speech Movement. After three crazed years in service of progressive cause, it changed its name to Bereley Graphic Arts, an admittedly more bourgeois name but it at least did not sugget that prnting would be done for free. In addition to the political work that they did, they were not above the lucrative business of printing porn and they did work for the followers of Meyer Baba.

After several moves, they settled at 1705 Grove (not King), the today-home of David Goines.

After several moves, they settled at 1705 Grove (not King), the today-home of David Goines.

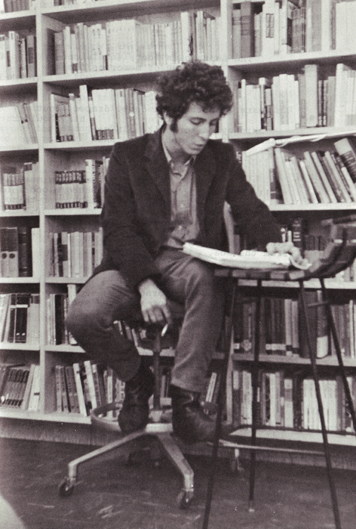

Goines had been involved with the Press in all its iterations, and still is. He has written about the history of press. It is good reading. For years, 1705 Grove had been Linefelter’s Shoe Repair Shop. There was a beauty salon next-door, which vacated the premises when the hippies moved in. The Free University of Berkeley moved in, and next to them the Tribe office. Goines was also involved with the San Francisco Express Times, an underground newspaper with strong Berkeley ties. I am going to pass on full treatment of the Express Times here, but if you want,

A group calling itself the Telegraph Avenue Liberation Front, which appears to have been much more notional than real, put out several publications in 1969.

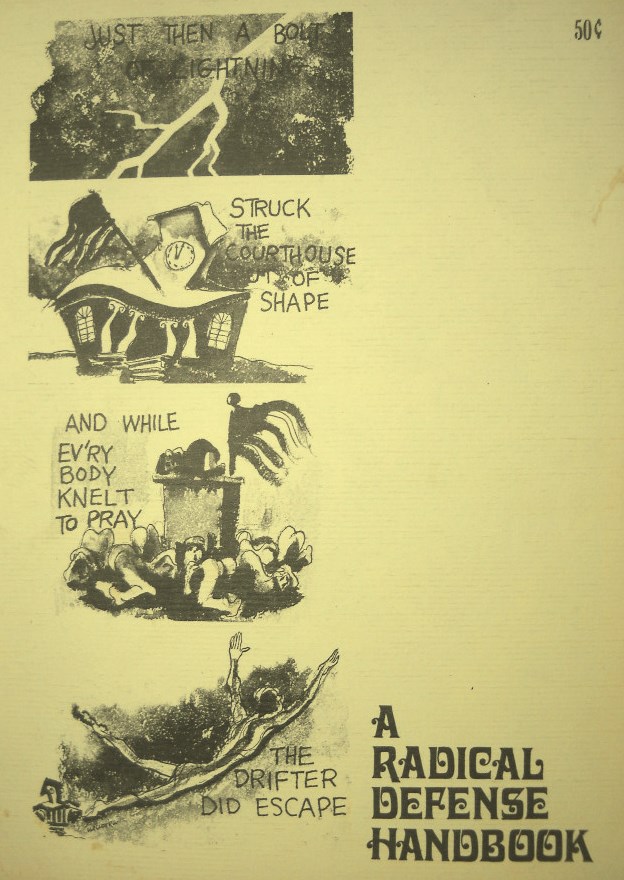

These were printed by Noh Directions Press on an A.B. Dick 360 named “Edna” at a house they called “The Boneyard” at 5th and Delaware.

These were printed by Noh Directions Press on an A.B. Dick 360 named “Edna” at a house they called “The Boneyard” at 5th and Delaware.

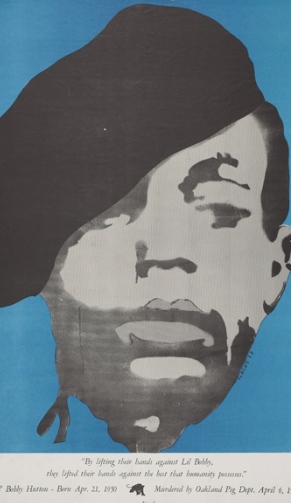

Dig the Dylan lyrics! “Drifter’s Escape”! Which Patti Smith covered pretty brilliantly. They dabbled in posters, such as this tribute to Little Bobby Hutton, who was killed by Oakland Police in 1968.

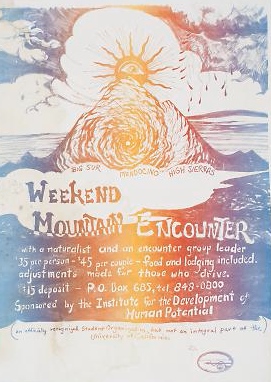

Dig the Dylan lyrics! “Drifter’s Escape”! Which Patti Smith covered pretty brilliantly. They dabbled in posters, such as this tribute to Little Bobby Hutton, who was killed by Oakland Police in 1968.  The name of the poster is “The White Ghost of Bobby Hutton.” The next poster, below, was printed for a Institute for the Development of Human Potential, a student organization at Cal.

The name of the poster is “The White Ghost of Bobby Hutton.” The next poster, below, was printed for a Institute for the Development of Human Potential, a student organization at Cal.  The political work that Noh Directions did served to subsidize the great love of the shop’s founders, poetry.

The political work that Noh Directions did served to subsidize the great love of the shop’s founders, poetry.  Richard Krech has spent a lifetime balancing politcs and poetry. The cover of this Noh Directions book of his poetry kind of says it all. Revolution. Poetry.

Richard Krech has spent a lifetime balancing politcs and poetry. The cover of this Noh Directions book of his poetry kind of says it all. Revolution. Poetry.

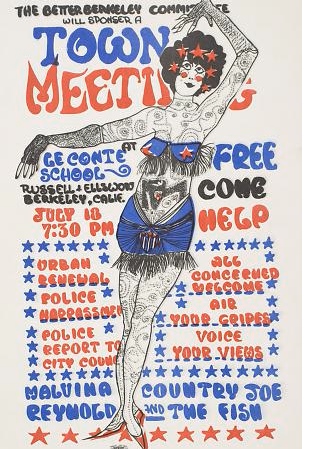

He stopped writing poetry in the mid 1970s, went to law school, and has practiced criminal defense work in Oakland since then. And then started writing poetry again. I get it. Art and politics, politics and art. P.S. to Noh Direction. Alta Gerrey, John Simon’s soon-to-be ex-wife, took the press and started Shameless Hussy Press in Oakland.  There she printed the first edition – now Oh So rare – of Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf. That book blew me away when I read it I was living in a UFW house on Central Street in Salinas, a few blocks north of our Gabilan Street office. It just blew me away. Posters were ubiquitous, like those from Noh Directions above, like those in the Red Sun Rising posting. One seen on Telegraph that blended countercultre with counter-politics was this:

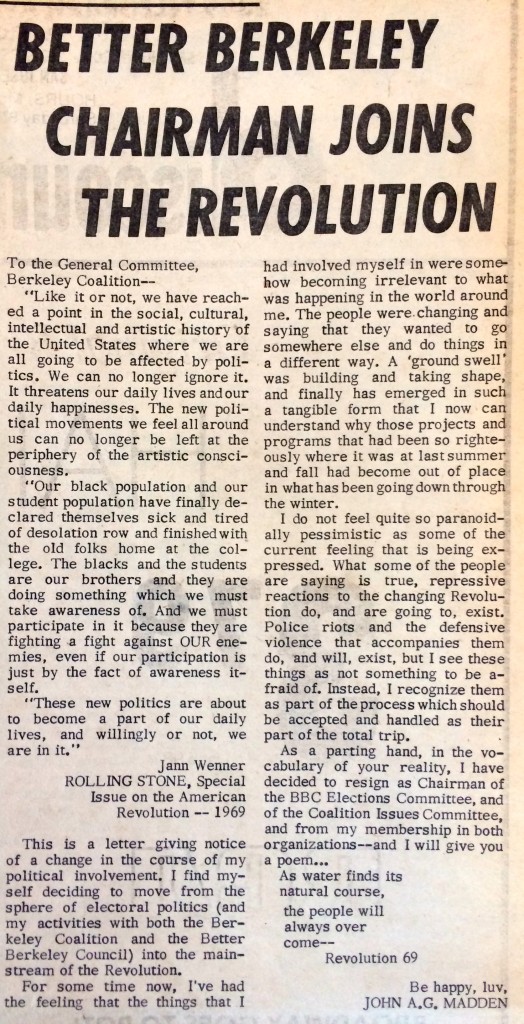

There she printed the first edition – now Oh So rare – of Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf. That book blew me away when I read it I was living in a UFW house on Central Street in Salinas, a few blocks north of our Gabilan Street office. It just blew me away. Posters were ubiquitous, like those from Noh Directions above, like those in the Red Sun Rising posting. One seen on Telegraph that blended countercultre with counter-politics was this:  The Better Berkeley Committee was hard come, easy go. There was also the Better Berkeley Council.

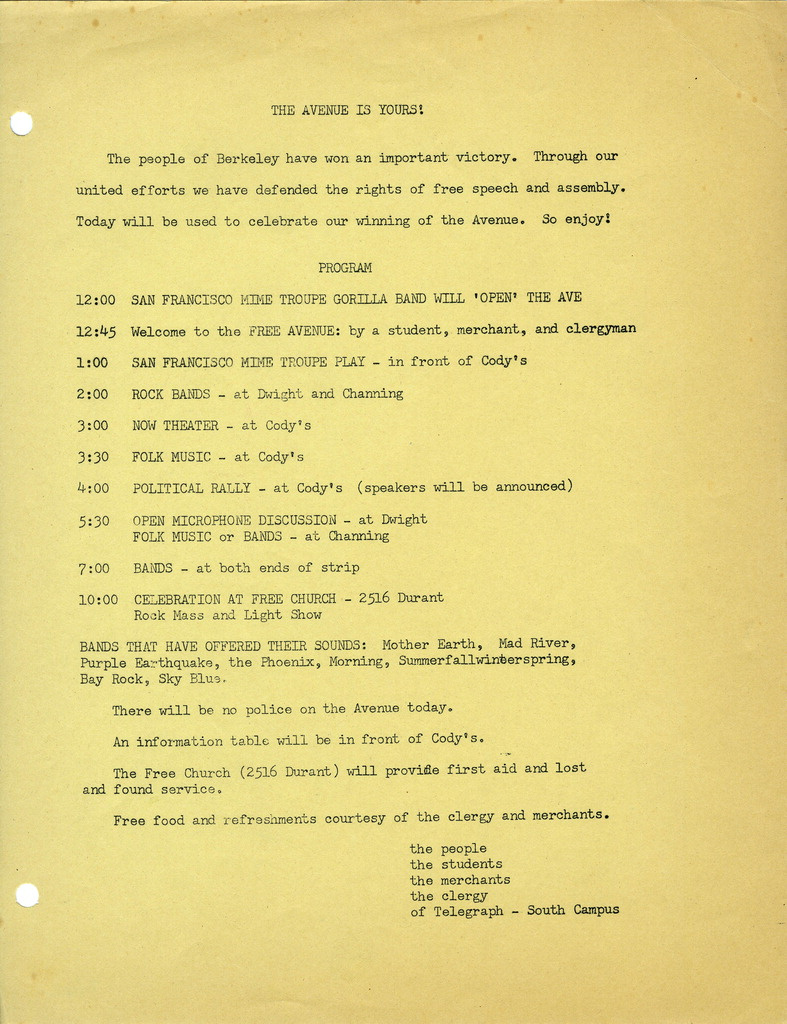

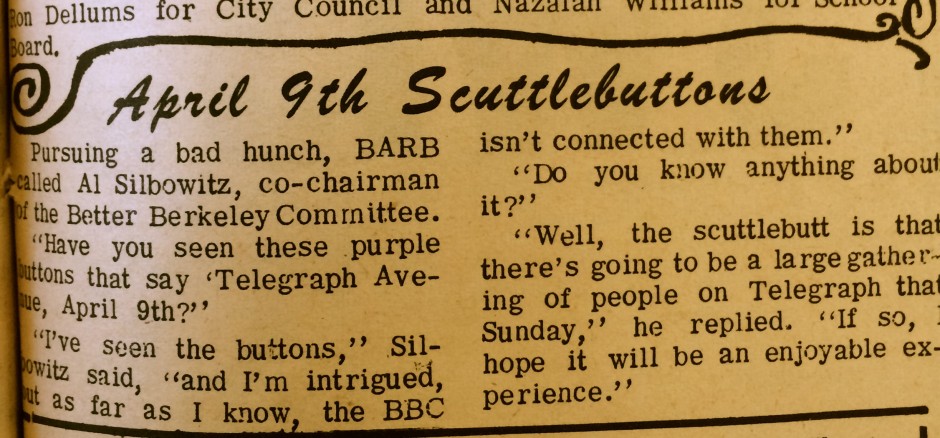

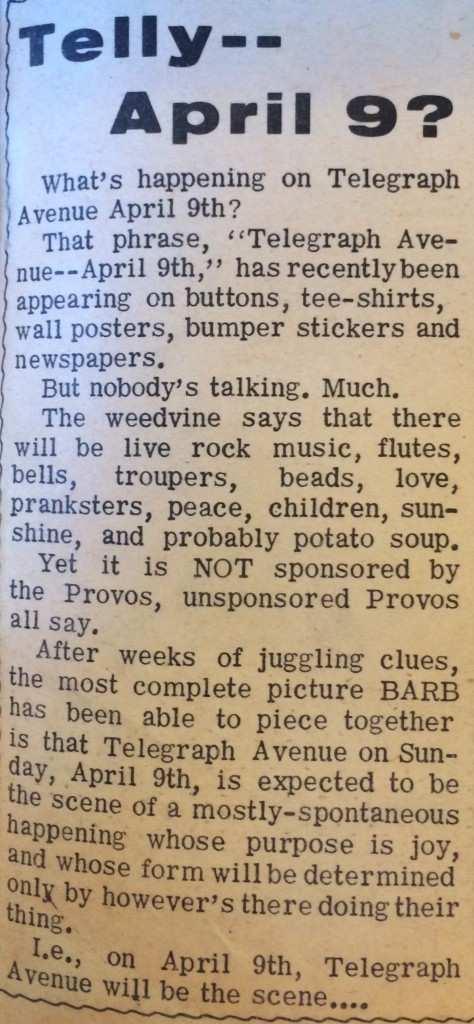

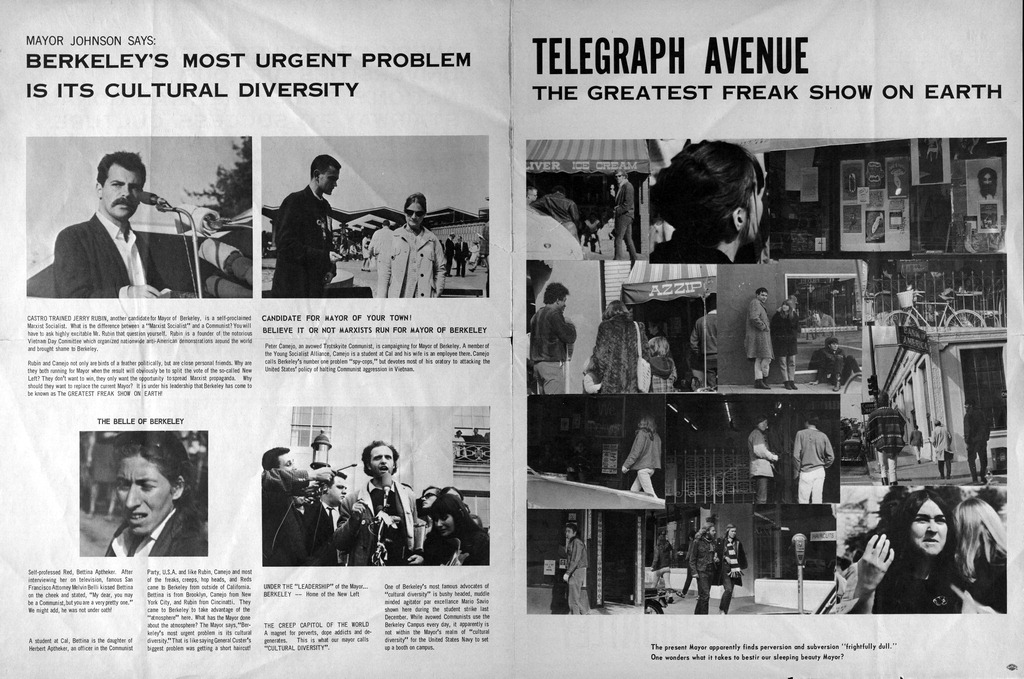

The Better Berkeley Committee was hard come, easy go. There was also the Better Berkeley Council.  Michael Rossman, a central figure in the Free Speech Movement, wrote of the Better Berkeley Committee and “a year of fruitless dicking-around with the City government – committees, reports, petitions – trying for an experimental closure of Telegraph as a mall and for festivals. That didn’t work. So ‘someone’ printed buttons saying TELEGRAPH AVENUE / APRIL 9 and started handing them out. The Barb was on the story:

Michael Rossman, a central figure in the Free Speech Movement, wrote of the Better Berkeley Committee and “a year of fruitless dicking-around with the City government – committees, reports, petitions – trying for an experimental closure of Telegraph as a mall and for festivals. That didn’t work. So ‘someone’ printed buttons saying TELEGRAPH AVENUE / APRIL 9 and started handing them out. The Barb was on the story:

It happened. It was the scene. It was a happening whose purpose was joy.

The Better Berkeley Committee went away shortly after this happiness on Telegraph:

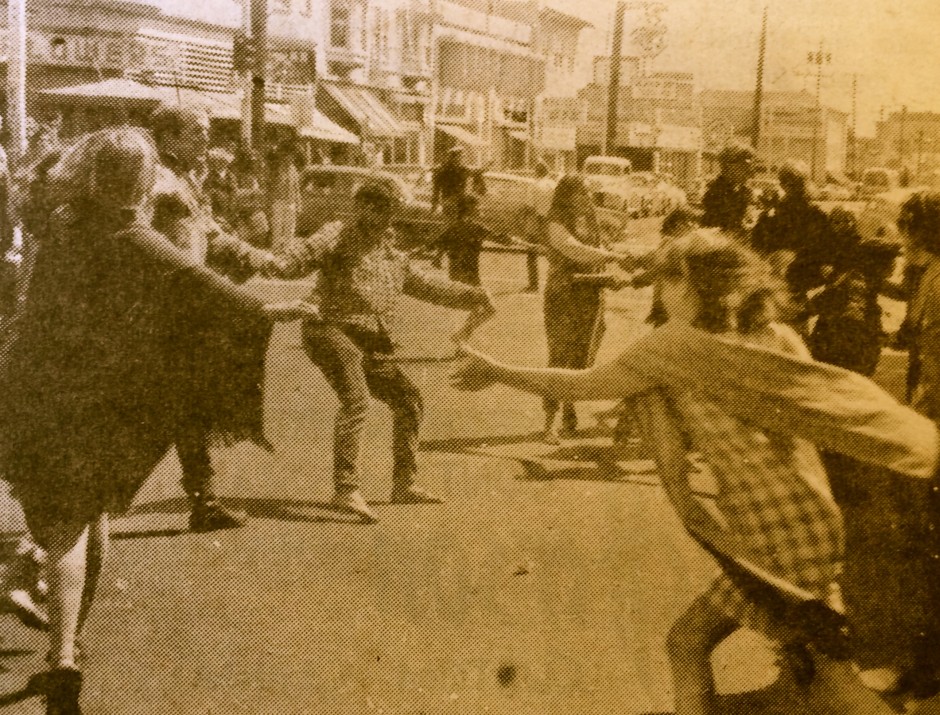

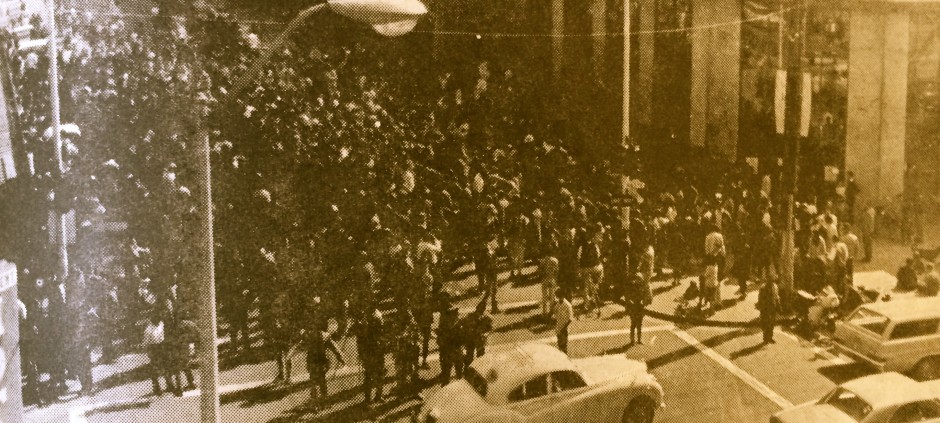

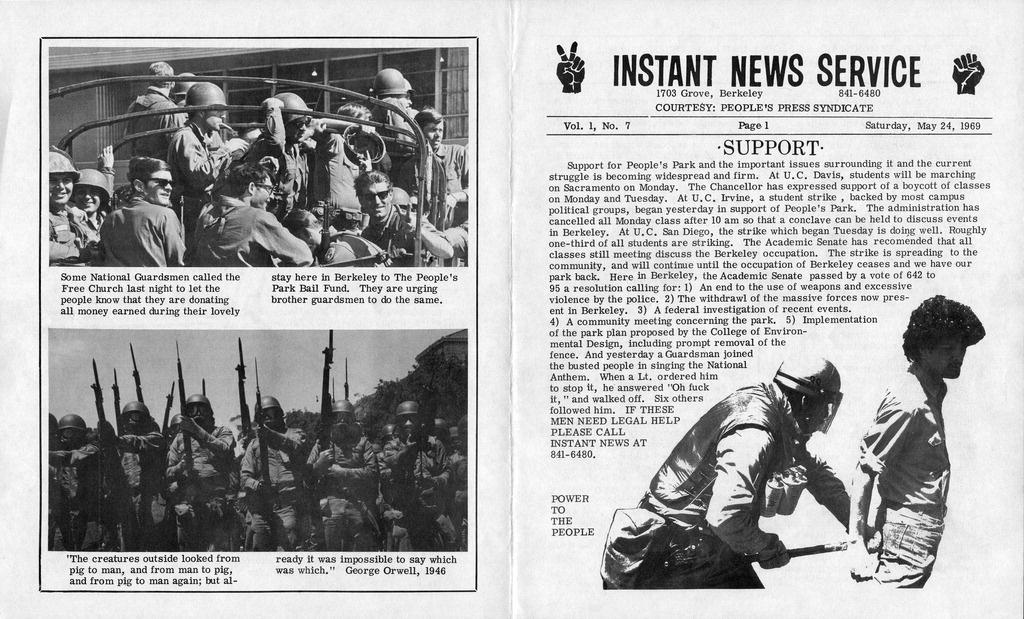

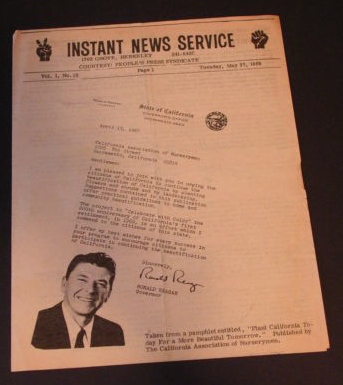

Berkeley Free Press,Noh Directions and other movement print shops were to some extent competitors, some extent collaborators. When the hard rain fell on People’s Park in 1969, they joined forces to print daily updates. The production values were stunning:

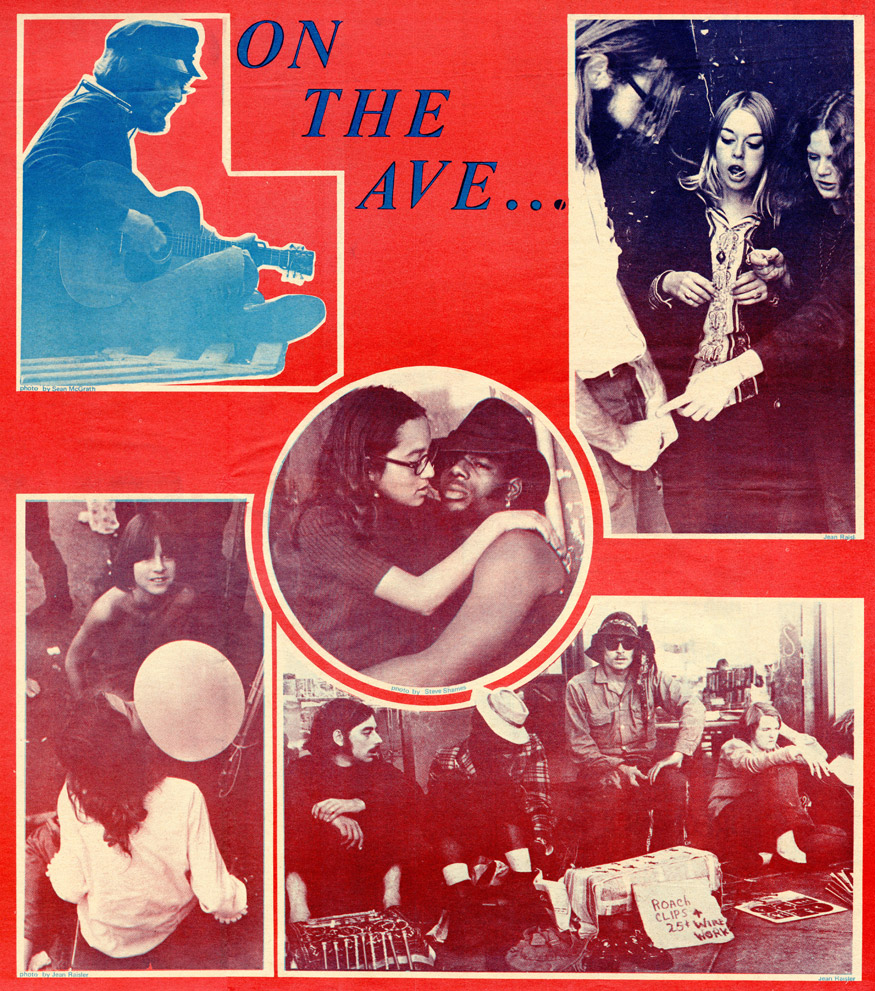

Other street publications celebrated Telegraph. They are hard to find. Almost impossible.

Other street publications celebrated Telegraph. They are hard to find. Almost impossible.

Comics

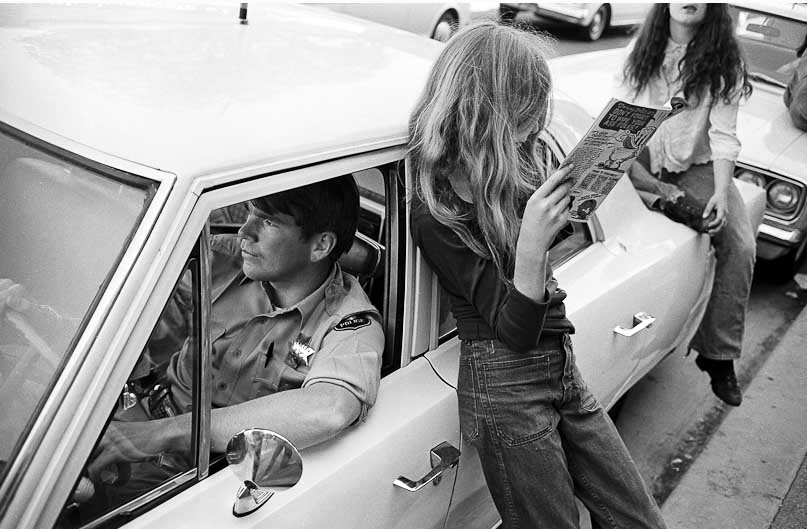

When my friend overheard my talking about posting about underground comics on Telegraph, he was worried. He did more than just express his concern. He pulled out an 8 by 10 glossy photo:

“What does this mean to you?” he asked. “Danger?” Yes. He cautioned that the world is full of Very Smart people who know a lot about underground comics and who will pounce on me if I get something wrong. I get it. I will proceed with caution. And be very general.

I am impressed with three underground comic book presences on Telegraph, one of which is a reach which I will execute with grace and sensitivity.

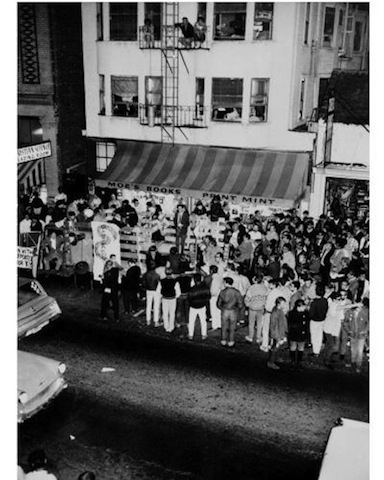

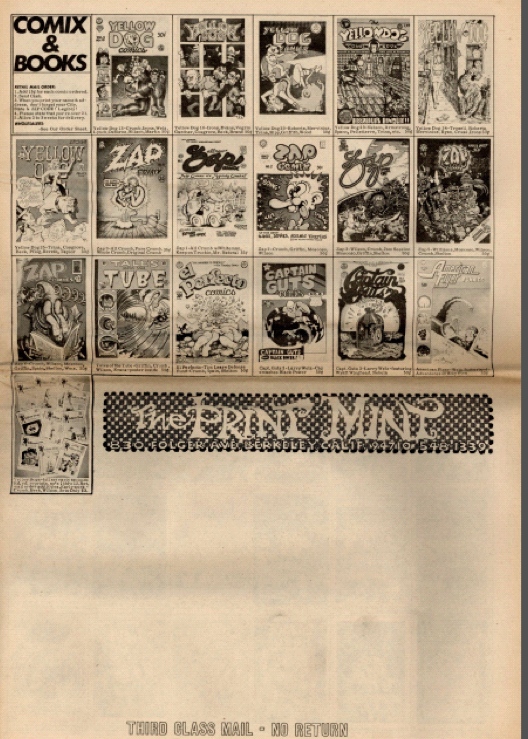

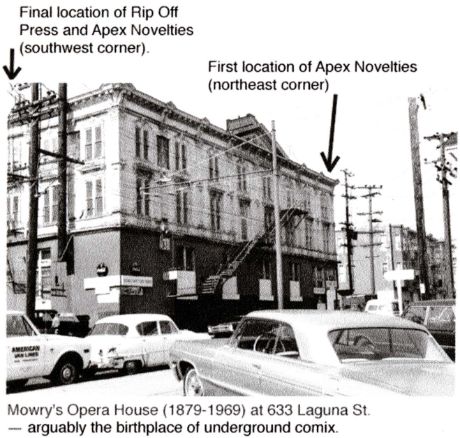

First – the Print Mint. Don and Alice Schenker opened the Print Mint as a picture-framing shop on Telegraph in 1965.

You can see it in many of the photos I have posted of Moe’s, on account of the Schenkers and Moe were friends from way back and way far away, and the businesses started joined at the hip.

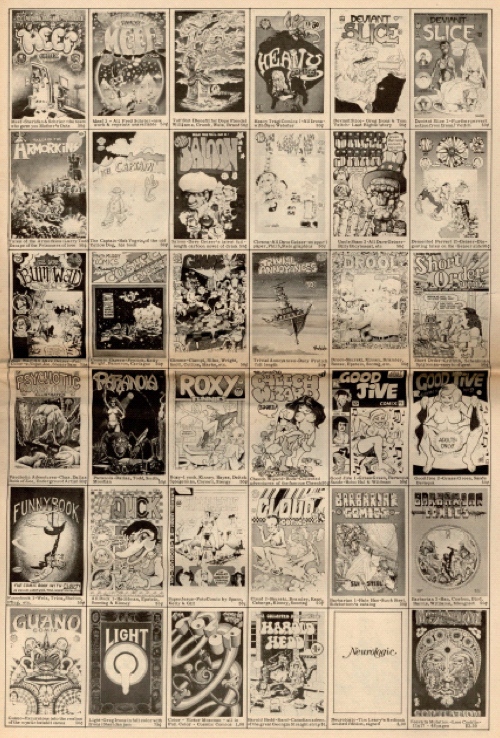

The Print Mint eventually moved out of Moe’s, and expanded, first as a retailer of posters and fine art reproductions and then to rock posters and, relevant here, to underground comics. For several years, underground comics were the lifeblood of the store. Here is their catalog of comics from the early 1970s:

Many were one-issue comics. Many were crude. All rejected society’s norms. All were creative and bright manifestations of changing culture.

They produced, published, and distributed, from Telegraph and a warehouse/print shop at 830 Folger Street. Do you want to see the covers of some of the comics published by the Print Mint?

What an explosion of creativity! They were of the street, for the street.

Nothing new about that. They always were.  Just a different street. The Schenkers were arrested in 1969 and charged with publishing pornography, thanks to Zap No. 4. At least I think that they were. Similar stories exist about Moe’s, and the stores were conflated at the time, so the stories may be. In any event, Zap got them in trouble. Simon Lowinsky, who owned the Phoenix Gallery on College Avenue (which the feminists at the Tribe found offensive), was arrested on similar charges for exhibiting original Zap art. Lowinsky beat the rap, and the City dropped charges against the Print Mint.

Just a different street. The Schenkers were arrested in 1969 and charged with publishing pornography, thanks to Zap No. 4. At least I think that they were. Similar stories exist about Moe’s, and the stores were conflated at the time, so the stories may be. In any event, Zap got them in trouble. Simon Lowinsky, who owned the Phoenix Gallery on College Avenue (which the feminists at the Tribe found offensive), was arrested on similar charges for exhibiting original Zap art. Lowinsky beat the rap, and the City dropped charges against the Print Mint.

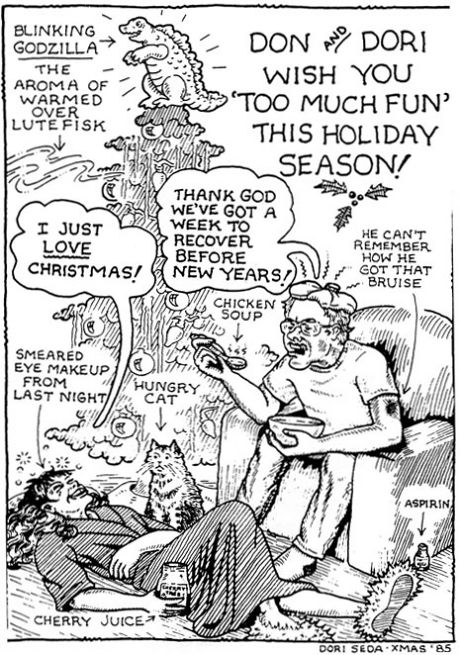

The second comics/comix presence on Telegraph was the work of Berkeley geniuses Don Donahue and Dori Seda.

They started out in San Francisco. But soon came to Berkeley.

They worked out of and lived in a warehouse on the northwest corner of Adeline and Stuart. I knew this as Scooby’s Toys in the 1980s.

Many of the comics that they produced and distributed and which were sold on Telegraph are not specifically family-friendly, and so I have posted them on a separate page. Disclaimer. Warning. Assume the risk. And check them out if you want.

Donahue also printed for the Black Panthers and the Symbionese Liberation Army. I mention that for a specific reason. Warren Zevon’s “Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner” is a second song that mentions Berkeley.

Now it’s ten years later but he still keeps up the fight/ In Ireland, in Lebanon, in Palestine and Berkeley / Patty Hearst heard the burst of Roland’s Thompson gun and bought it.

For those not old enough to remember, the Symbionese Liberation Army kidnapped heiress Patty Hearst on February 4, 1974.

She was living in this apartment on Benvenue with her boyfriend Steven Weed. So that’s a neat little package as far as I am concerned.

Written word → Comics → Donahue → SLA → Patty Hearst → Warren Zevon

Going down to Adeline for Donahue and Dori was the reach. The third comic presence on Telegraph is a cake walk – on point, no reach, part of Telegraph.

Jesus, that was obvious. Too obvious?

Pynoman from the Psycotic Pineapple entertains here.

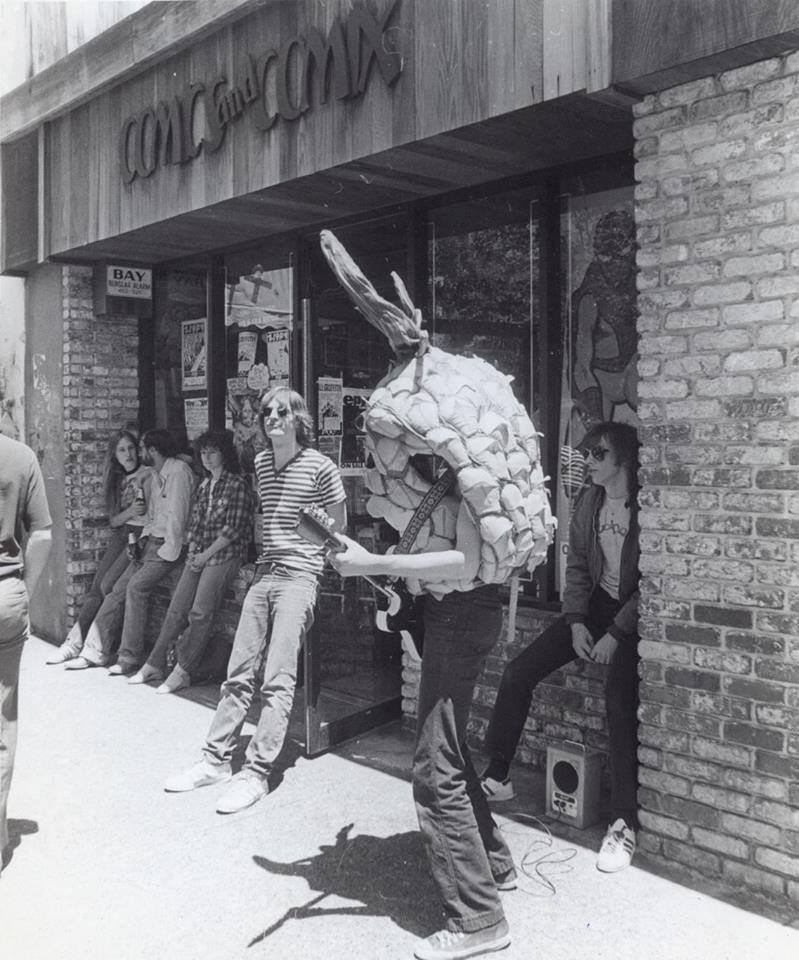

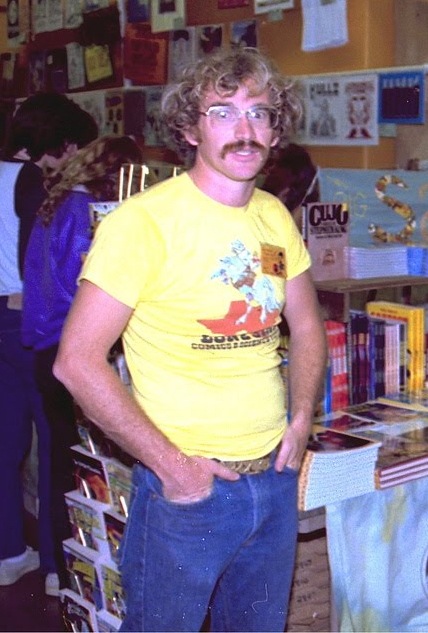

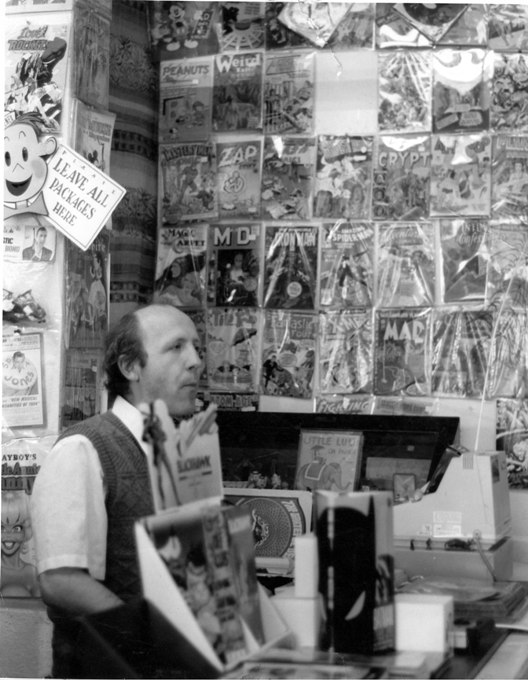

In 1972, an undergraduate student at San Jose State and a two others opened Comics and Comix at 2502 Telegraph. His name was Bud Plant.

Bud Plant had two partners. One was John Barrett.

The other was Robert Beerhom. Here is the store.

As far as I can tell, Comics and Comix was fairly eceumenical – traditional comics, underground, new-school fantasy.

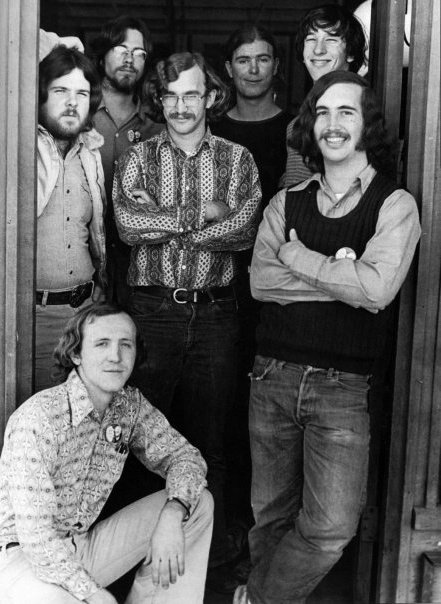

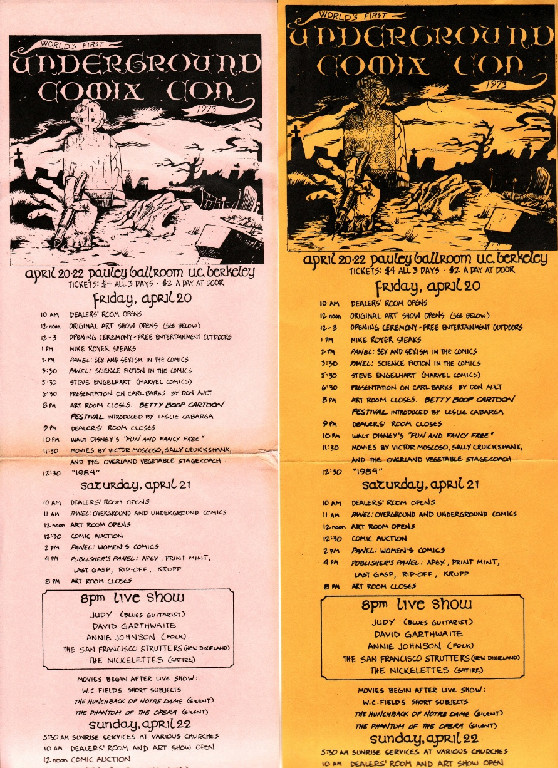

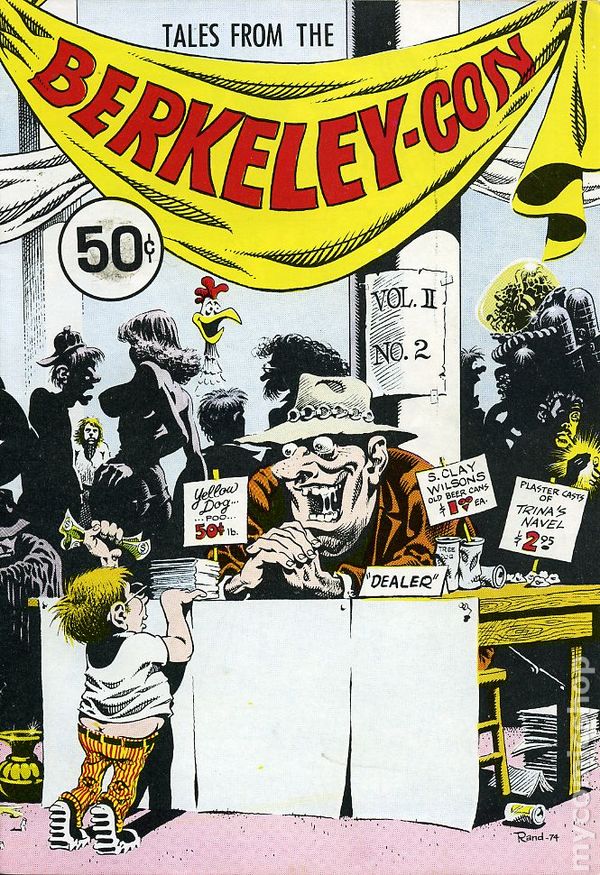

This photo is of the staff in 1972. Smart. Funny. Obsessed. Very obsessed, and comfortable with it. Comics were booming.  This photo was from New York, not Berkeley. But it captures the passion of comics/comix collectors of the era. And illustrates my friend’s point – every one of these Very Smart people could shred everything that I have said about comics/comix, as general and careful as I have been. So, though, thanks to Bud Plant, the first Bay Area comics convention took place on campus, sponsored by Comics & Comix – Berkeleycon 73. Jack Jackson, a legend, designed the program:

This photo was from New York, not Berkeley. But it captures the passion of comics/comix collectors of the era. And illustrates my friend’s point – every one of these Very Smart people could shred everything that I have said about comics/comix, as general and careful as I have been. So, though, thanks to Bud Plant, the first Bay Area comics convention took place on campus, sponsored by Comics & Comix – Berkeleycon 73. Jack Jackson, a legend, designed the program:

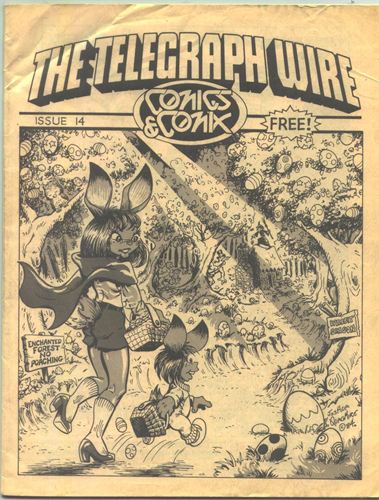

Comics and Comix did some pubishing too. Nowhere near the volume and not the underground genre of Print Mint and Donahue, but cool stuff. From here. From Telegraph Avenue. Want to see the covers of some of the comics he published?

And for a few years they published a trade magazine that I include because of (1) very cool graphics and (2) mention of Telegraph in the title.

After the Goldrush

Of course. An intuitively obvious musical choice for this section. You already know what it is going to be:

It is a good song. Still. Always. The written word, the printed word, did not die with the Golden Age of Telegraph Avenue.

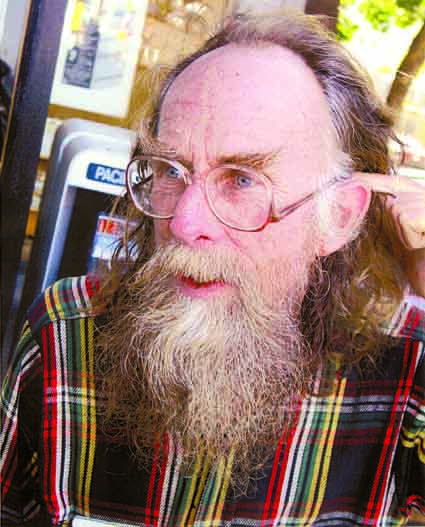

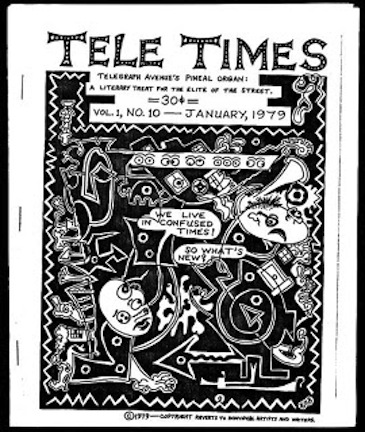

A later but still Perfect chronicle of not-quite-as-old-but-still-weird Telegraph is the run of the Tele Times, an irregular paper put out by Bruce N. Duncan between 1978 and 1982.

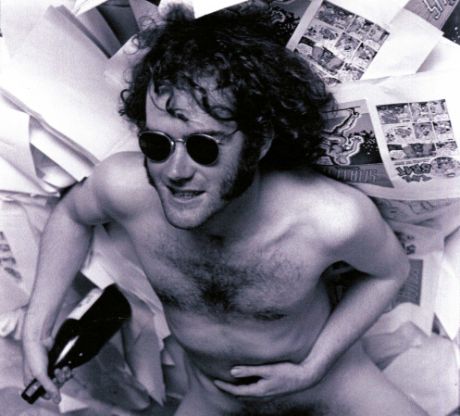

Duncan was considered a genius of the underground comics world. You can see samples of his comics here:

Duncan was considered a genius of the underground comics world. You can see samples of his comics here:

He was an insider in the world of outsiders. He was one of the old weird geniuses living in the Berkeley Inn at Telegraph and Haste until the fires and wrecking ball. Duncan’s friend Ace Backwards described a typical Duncan dinner, bought at Fred’s Market on Telegraph: “a half dozen deviled eggs, a package of baloney, a chunk of cheddar cheese, some cottage cheese, two tall cans of Olde English, and a pack of Basic 100s.” Are we getting the picture? Tom Spurgeon and Ace Backwards wrote compelling obituaries when Duncan died in 2009. This CBS film clip captures him and his world pretty well. Up to a point.

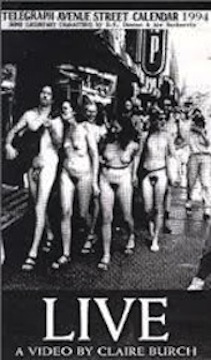

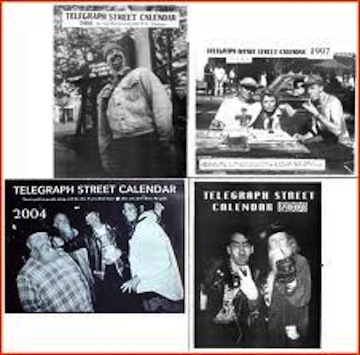

In the late 1990s, Duncan, Ace Backwards, and others published a series of Telegraph Street Calendars, a material celebration of non-material culture:

Yes, I agree, that would be a sight that offends pious eyes. I report. I don’t editorialize. I don’t censor. Much.

Yes, I agree, that would be a sight that offends pious eyes. I report. I don’t editorialize. I don’t censor. Much.

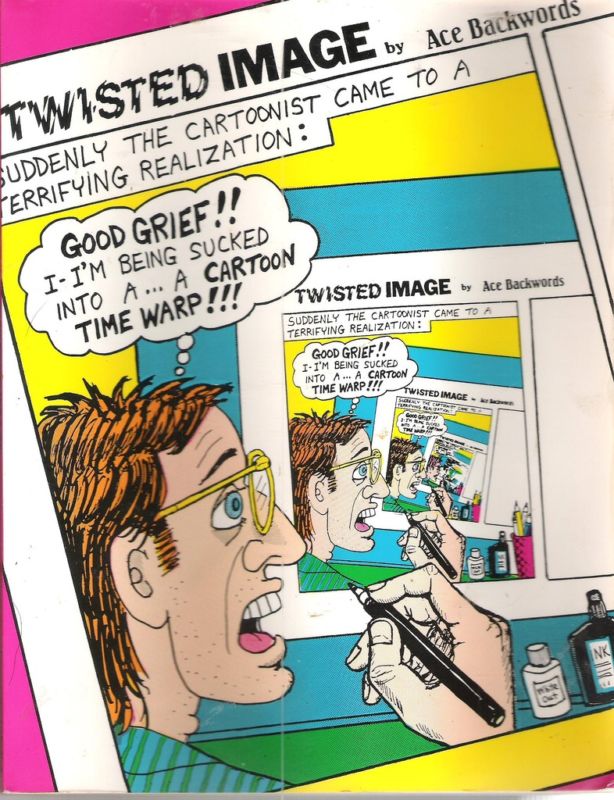

Another best-minds-of-my-generation genius presence on Telegraph is Ace Backwards. He is an underground comics artist.

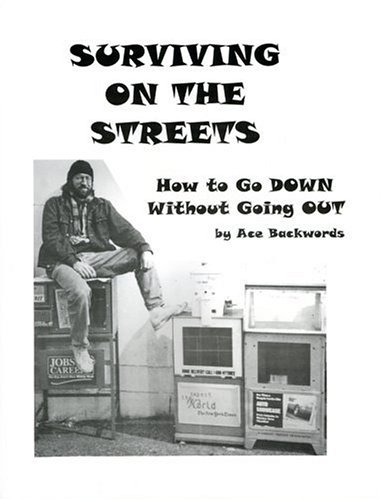

And is often without a home. He told us how to live without a home.

And is often without a home. He told us how to live without a home.

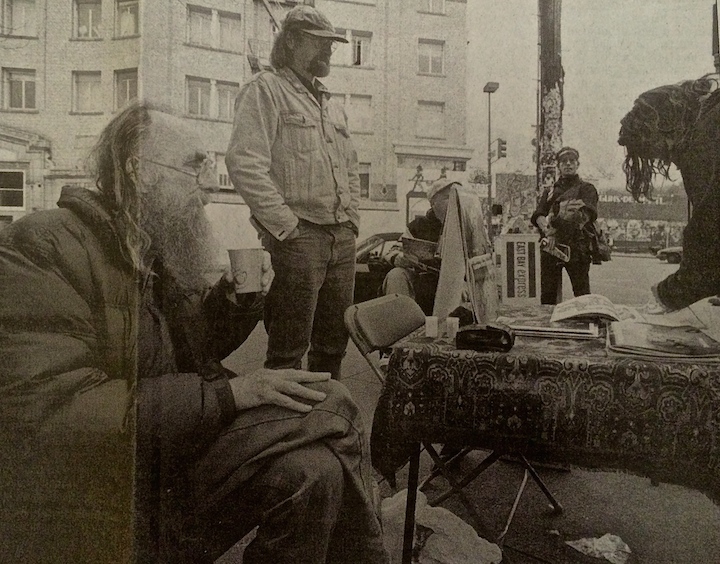

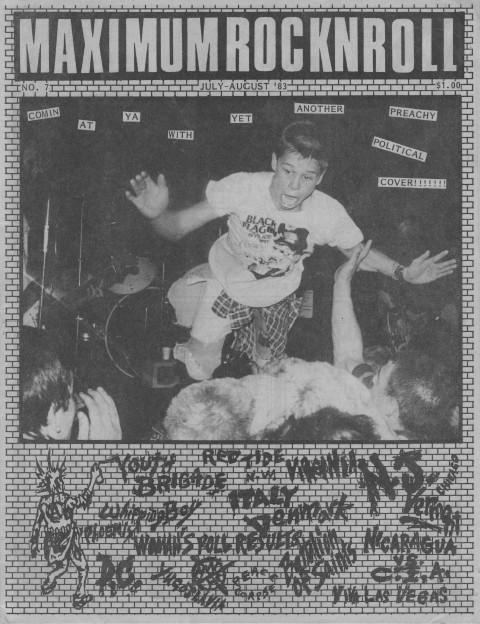

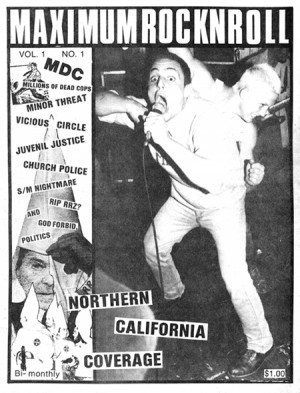

A final publication to mention that had a presence on Telegraph Avenue – Maximum Rock and Roll. In the early 1980s, Telegraph became one gathering place for the northern California punk scene.

A University of California employee, Tim Yohannan, launched a punk fanzine which was often seen on Telegraph.

Yohannan was a controversial figure – I know that much.

Ace Backwards doesn’t think much of him, and Green Day doesn’t think much of him. I know so little – as in nothing – about the punk scene that I would be crazy to get into a holy war about whether Yohannan was a good guy or a bad buy or both. His magazine was big on Telegraph during the 1980s. That’s all I know.

So, though, we have come to the end of a long post. Was it too long? And, yes, I know – I did not explore poetry. Even more than comics, I find poetry to be territory best left to those who understand it. As cartographers would write when they got to territory they did not know know –

Here there be dragons. Thus it is with poetry and me. So, for the time being at least, I will take a pass on the role of poetry on Telegraphy. I know it was there though.

This posting was a big job. I wonder if it makes any sense? It is not exactly linear, but, where is the rule saying it has to be linear. I went to my friend for his opinion about the posting. He had a faraway look in his eyes. He had been researching and listening to recordings of the theremin.

He had started innocently enough.

And then, as he is prone to do, he got lost in Very Weird, early theremin music – which was not totally inappropriate for our exploration of old weird Telegraph. I made a pot of tea of he sat down and went through the posting. His verdict?

Very much enjoyed your work here collecting these pictures and history. Also the murals page is incredible, thank you.