Religion and politics – oil and water, gas and fire – mixed on Old Weird Telegraph. Hare Kirshna’s (not treated here) and an old-school fire and brimstone Christian preacher and a new-school liberation theologist preacher shared turf with crazies and serious radicals running unsuccessfuly for public office, glorious defeat after glorious defeat. It was all in the old weird mix.

Church

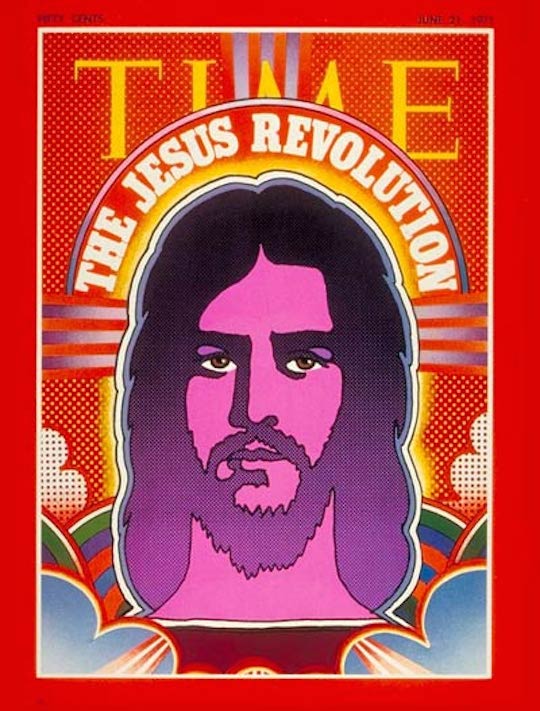

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw a Christian revival of sorts among the counter culture.

The mainstream revivalists were a fixture on Telegraph. Most prominent was the Christian World Liberation Front.

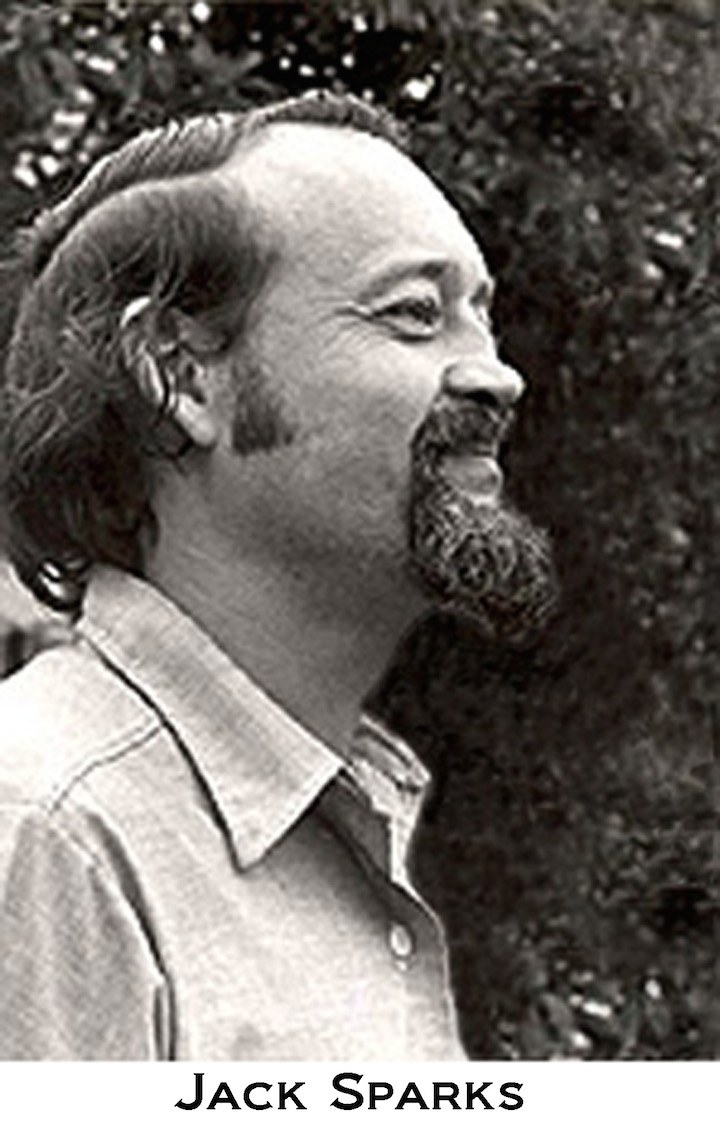

The CWLF was an offshoot of the Campus Crusade for Christ, and it targeted “the radical forces of darkness” in Berkeley and on Telegraph. It was led by Jack Sparks.

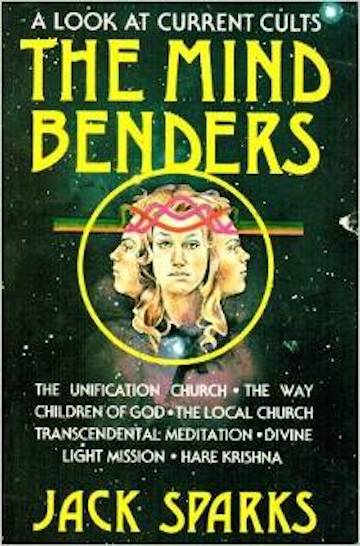

In the 1970s Sparks and the CWLF started an assault on “spritiual counterfeits.”

He eventually joined the eastern orthodox movement, but in the early 1970s his followers were a fixture on Telegraph.

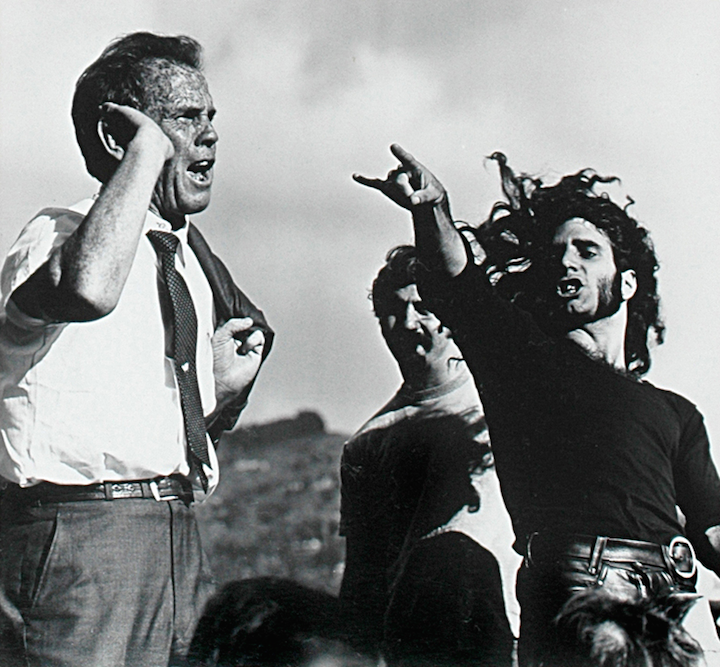

Here he is pictured with Holy Hubert – the real deal in street theater.

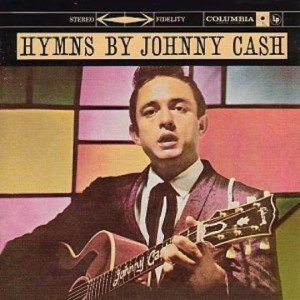

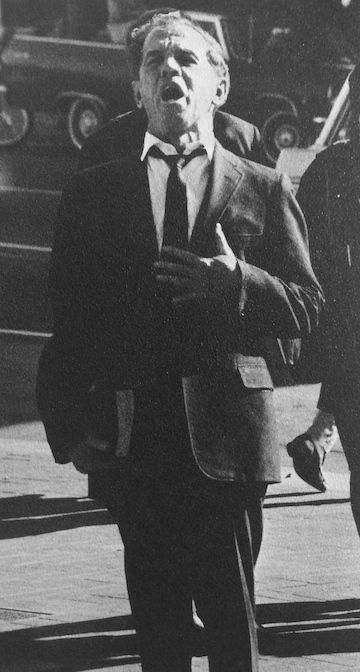

Holy Hubert. His name just about says it all. Hubert Lindsey, born in Georgia, a fixture preaching at Bancroft and Telegraph from the mid 1960s into the 1970s. He was in his 50’s when he started up in Berkeley. It is said that he fought the Hare Krishna’s for Sproul Plaza rights. Fought, as in fight. As in fisticuffs. He was an advocate of confrontational evangelism. The musical selection for Hubert and his old-time religion seems obvious:

With Johnny Cash singing, let’s see a few photos of Hubert on the street in Berkeley.

In the beginning, Hubert dressed like a southern preacher.

As times changed, Hubert went casual.

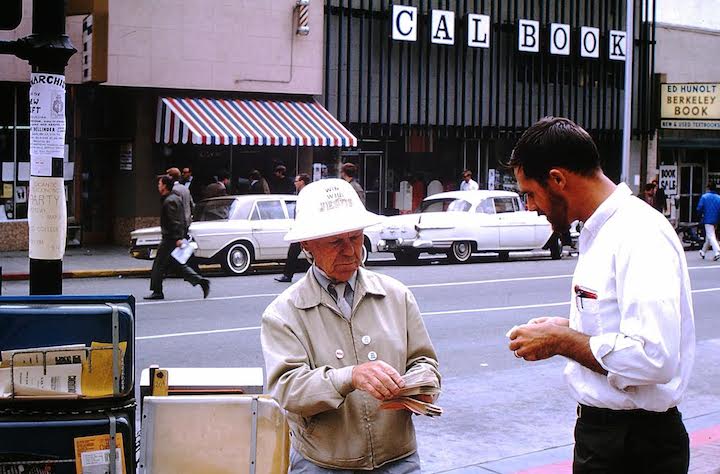

Tom Stetler sent me this photo, developed in 1965, that his parents took of Holy Hubert talking with graduate student Bruce Fowles.

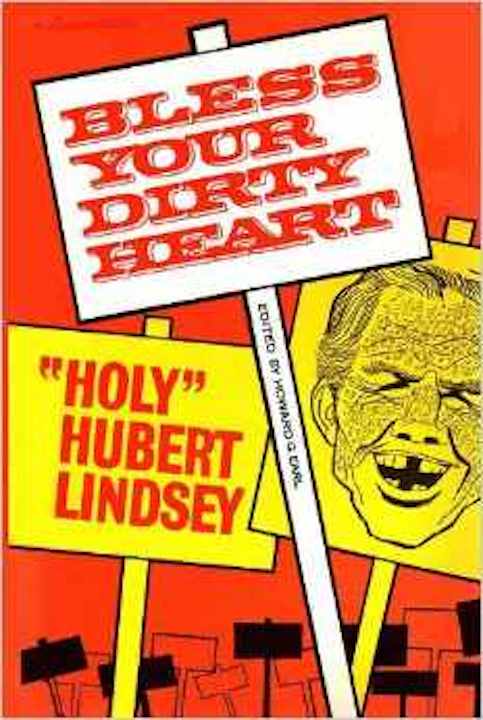

He had a circus barker quality to him, and was far more successful as an entertainer than he was at converting souls to Christ. His favorite line was “Bless your dirty heart,” which he used for the title of a book about his years as a street preacher.

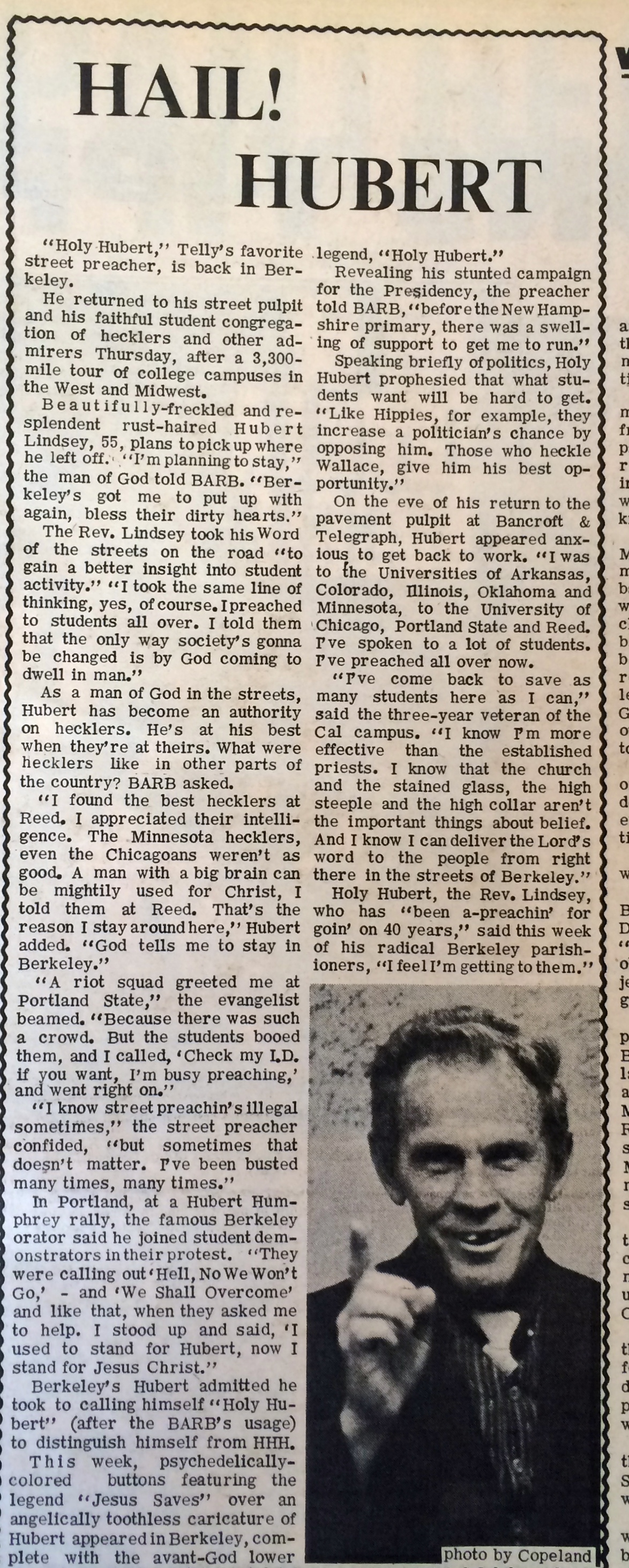

The left tolerated Hubert, even admiring him for his outsider status, as seen in this article from the Barb.

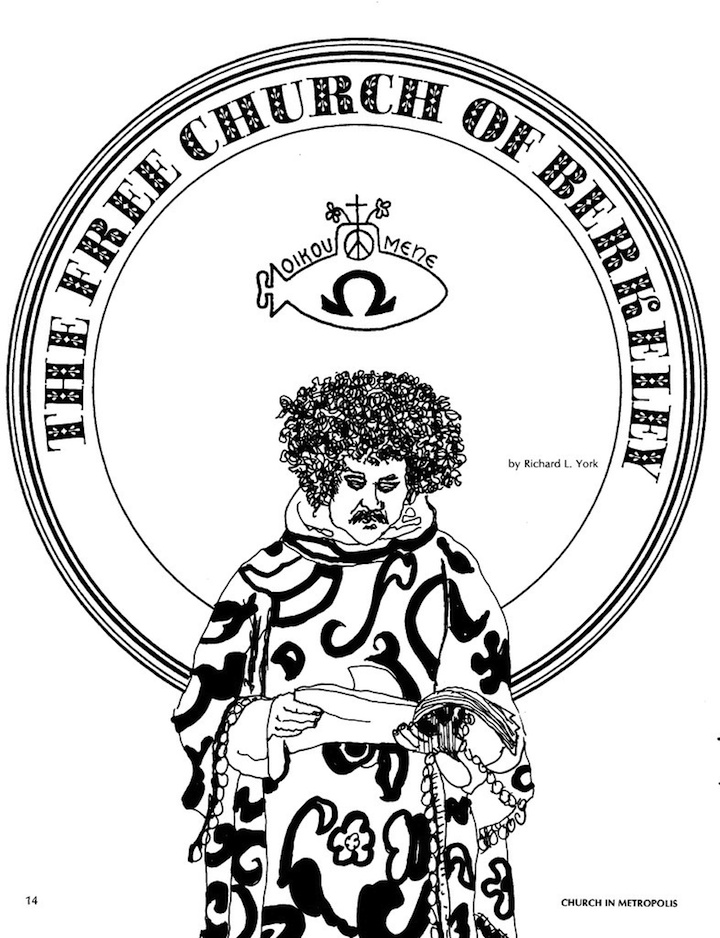

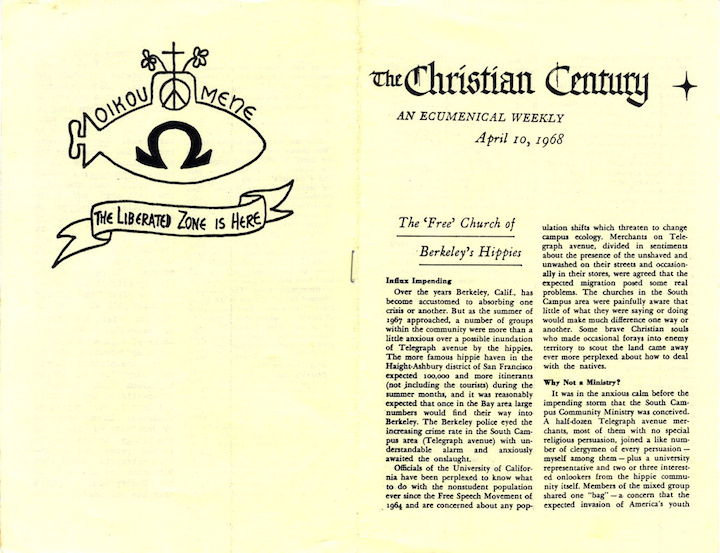

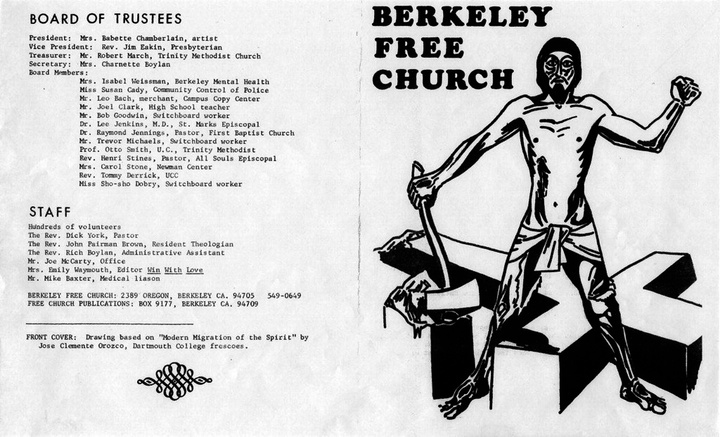

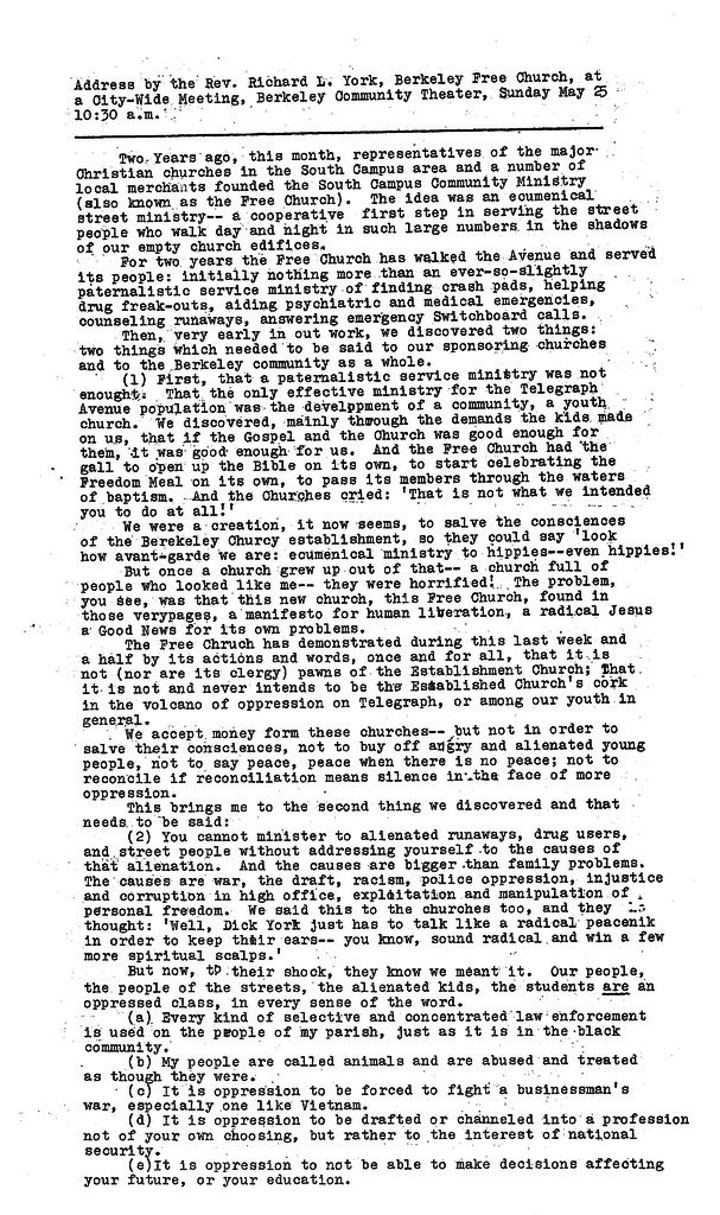

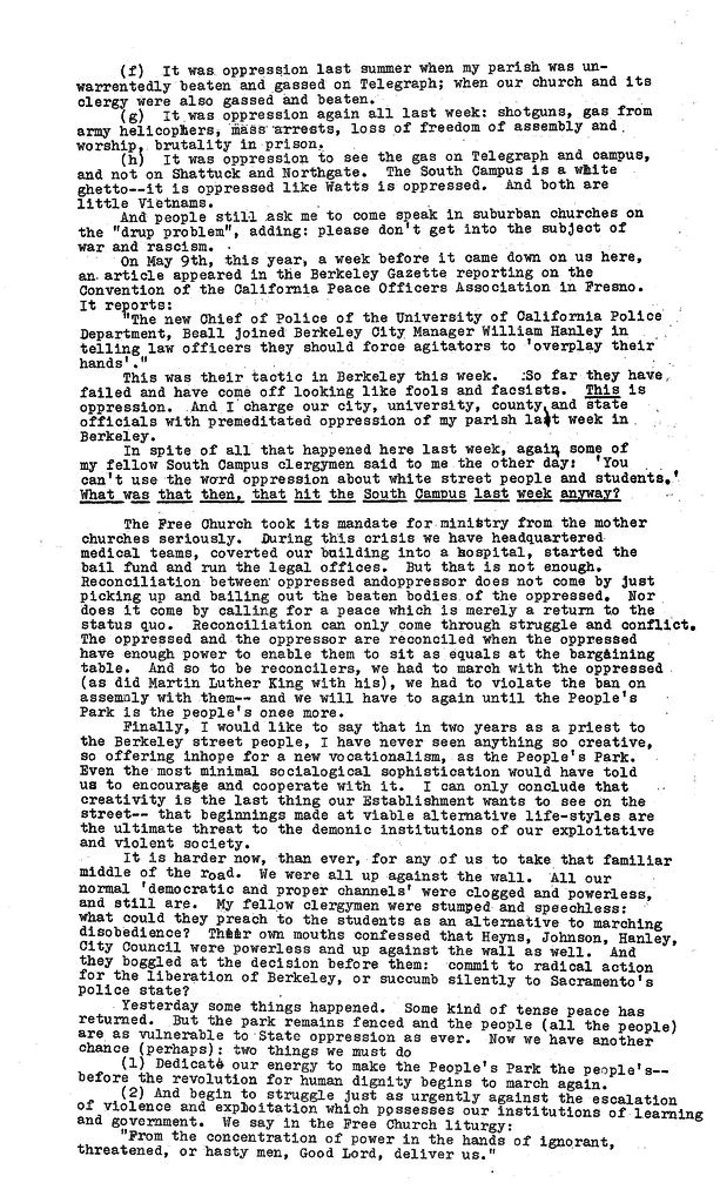

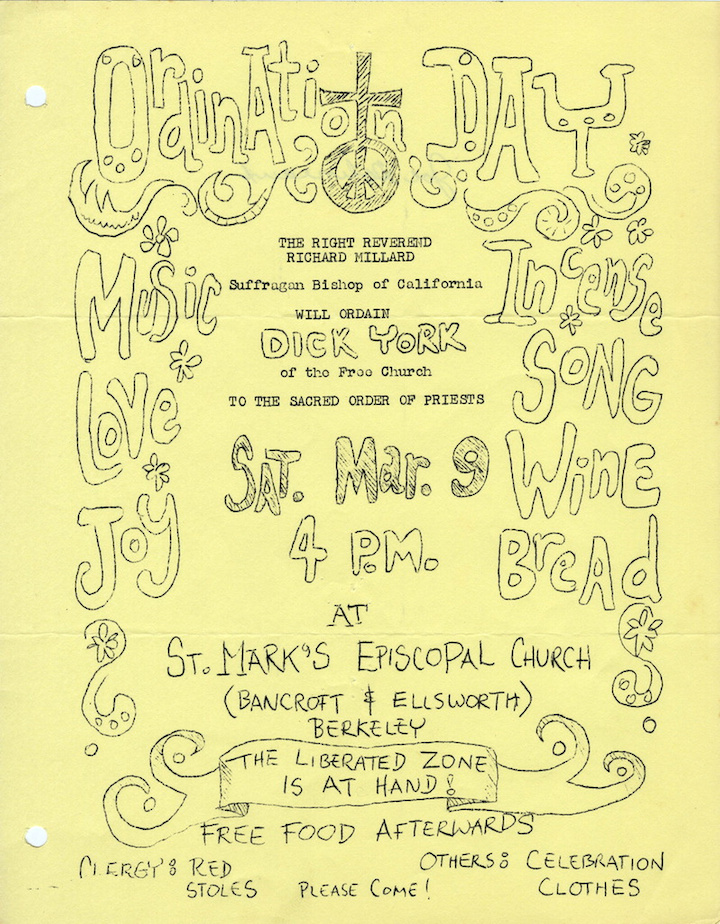

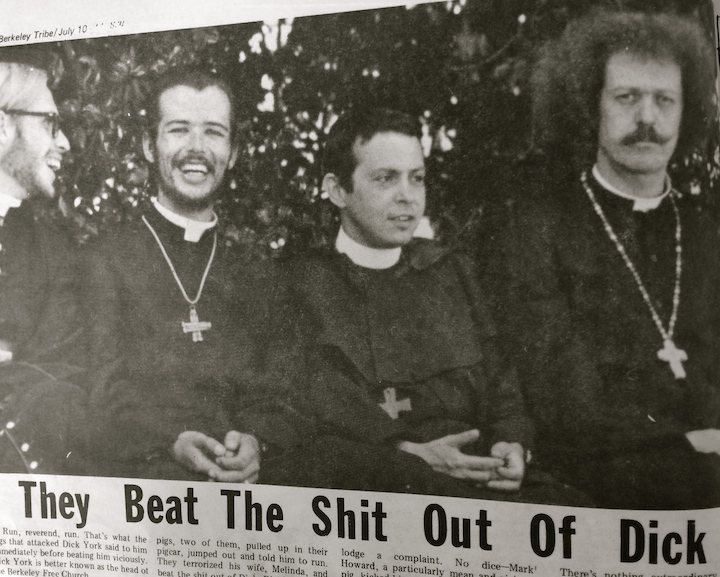

Same thing but very different – Richard York, an Episcopalian minister (my old team!) and the Berkeley Free Church. Once upon a time, on Telegraph Avenue in the 1960s and 1970s, Religion / Christianity / Jesus / Faith / Church were not the exclusive property of the Far Right and were not conflated with ultra-nationalism.

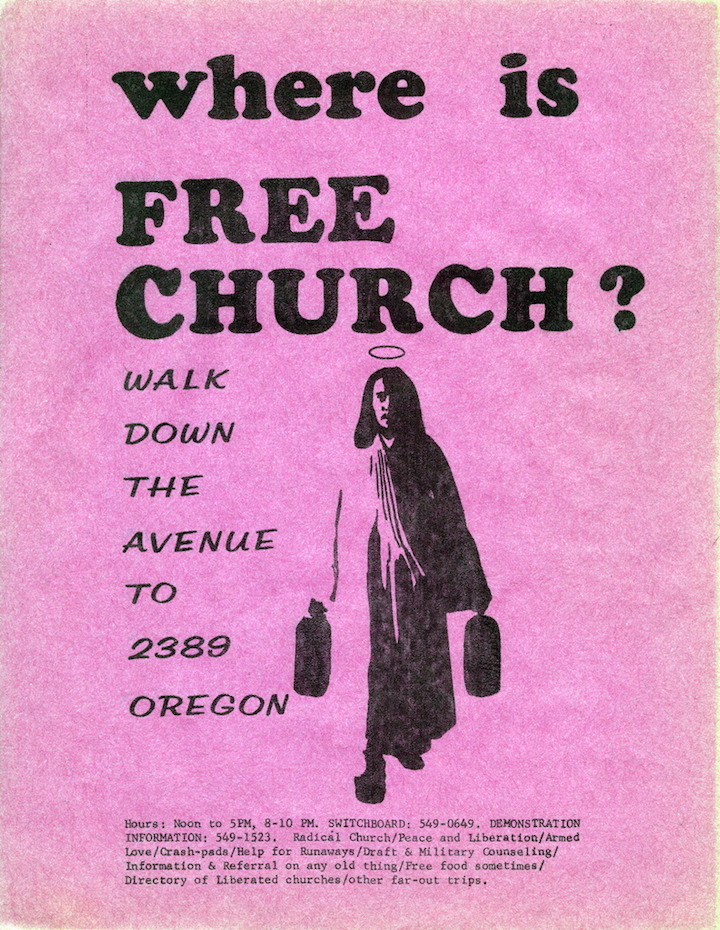

Richard York (“the hippie priest) and the Berkeley Free Church ministered to the needs of Telegraph’s young street-people/hippies/runaways/prematurely homeless. The church was originally sponsored by Berkeley merchants as the South Campus Christian Ministry. Over the years it operated on Haste Street, the Lutheran Church, Parker Street, Oregon Street, and Scenic Avenue.

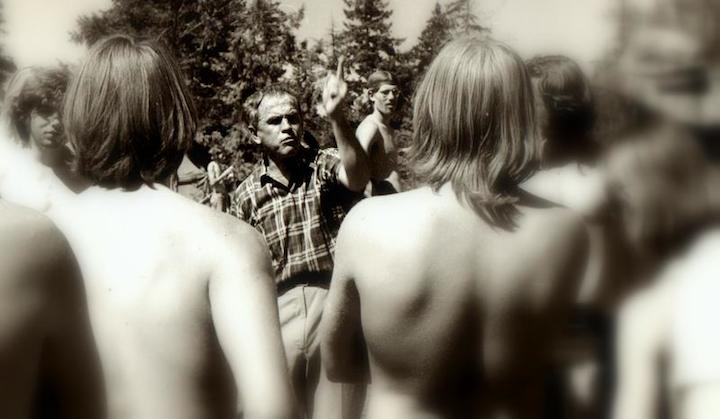

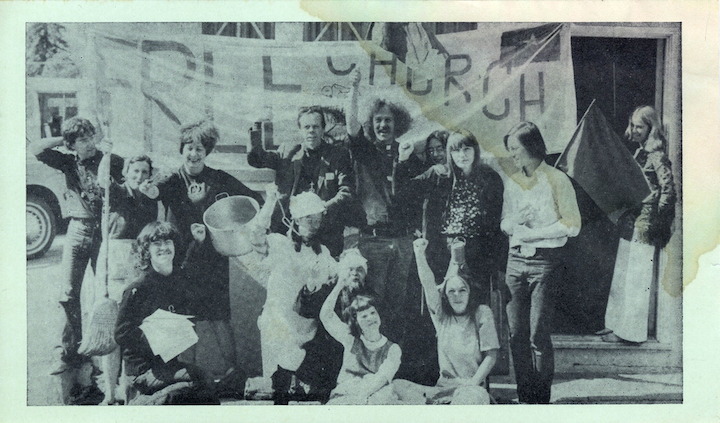

This photo was taken on August 12, 1967, during the Festival of the Virgin Mary on Haste Street. During the celebration (a religious be-in), York (with the frizzy hair) washed the feet of 12 hippies. He later wrote” Then we started washing hippies’ feet with big buckets of warm soap water and towels, in all these big bestments. It just blew these freaks minds. Cause, here were all these clergy washing their feet – which is just what it was all about.”

This photo was taken in People’s Park in 1969, pre-murder of James Rector. York claimed that at the height of the People’s Park tensions, National Guardsmen donated to his church.

York and the Free Church practiced without much preaching, a radical, liberation Christianity. The accompanying song could hardly be anything other than:

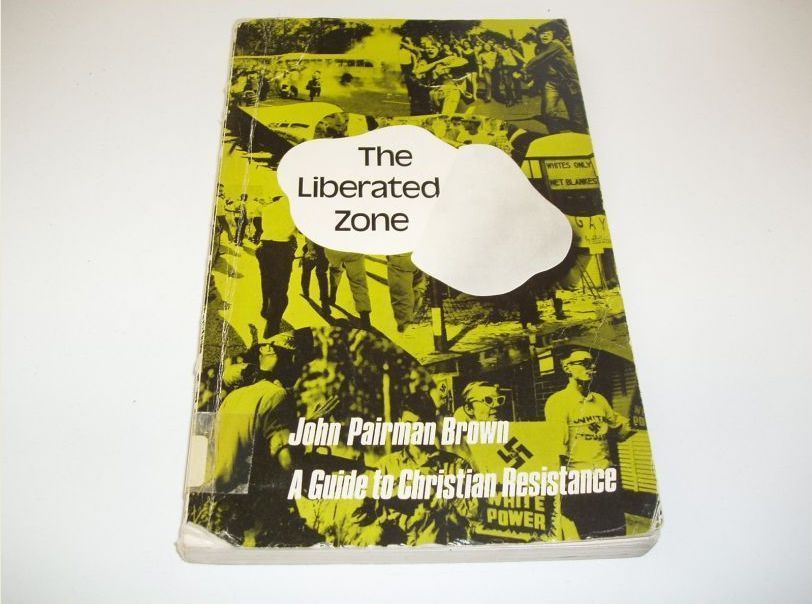

In contrast to Hubert’s evangelical book, theirs was The covenant of peace : a liberation prayer book by the Free Church of Berkeley compiled by John Pairman Brown and Richard L. York.

York was not alone in running the Free Church, although he was its most visible leader. John Pairman Brown was active, and his book The Liberated Zone conveys the radical, oppositional nature of the Free Church’s Christianity.

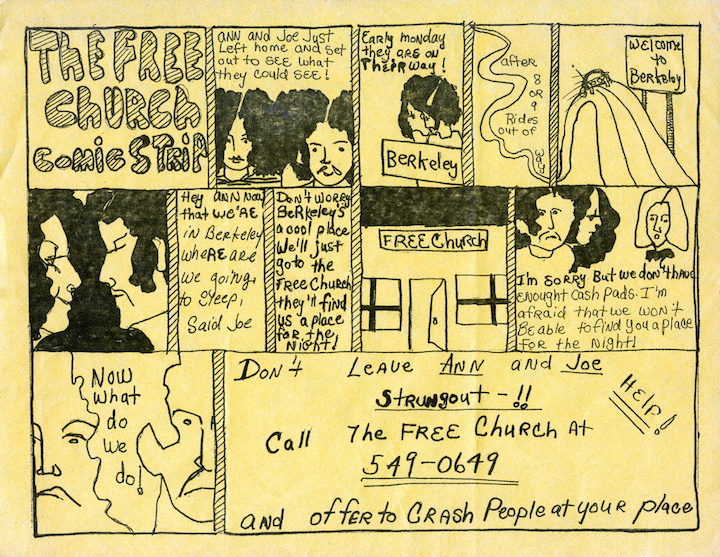

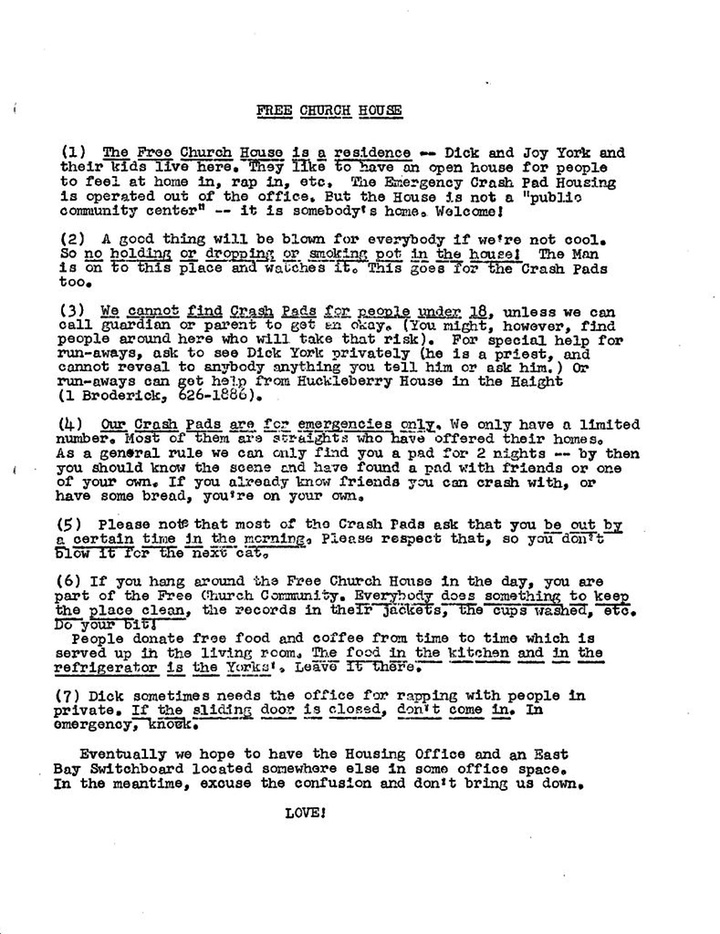

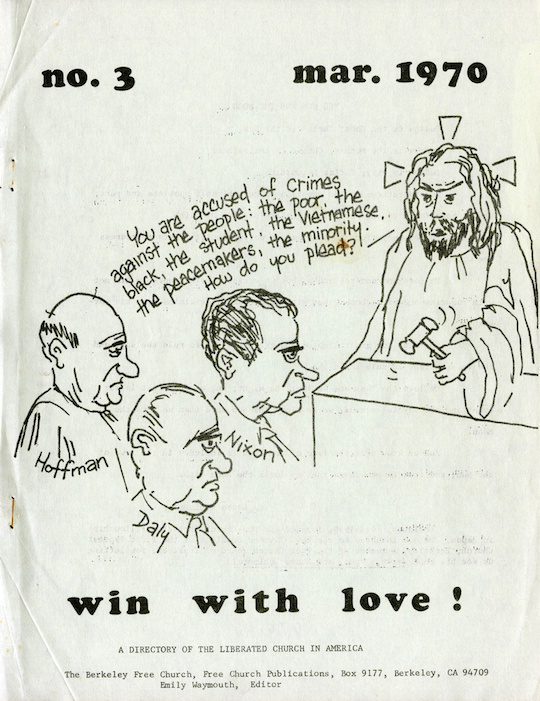

These documents give a flavor for the message and work of York and company:

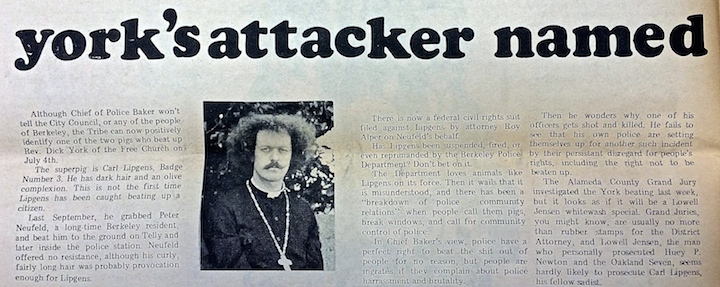

York was radical and he paid his radical dues.

As Telegraph burned out so did York. The demographics and aspirations of the transient youth on Telegraph changed, and years of constant, acute controversy, especially controversy when the issue was not the issue, took its toll.

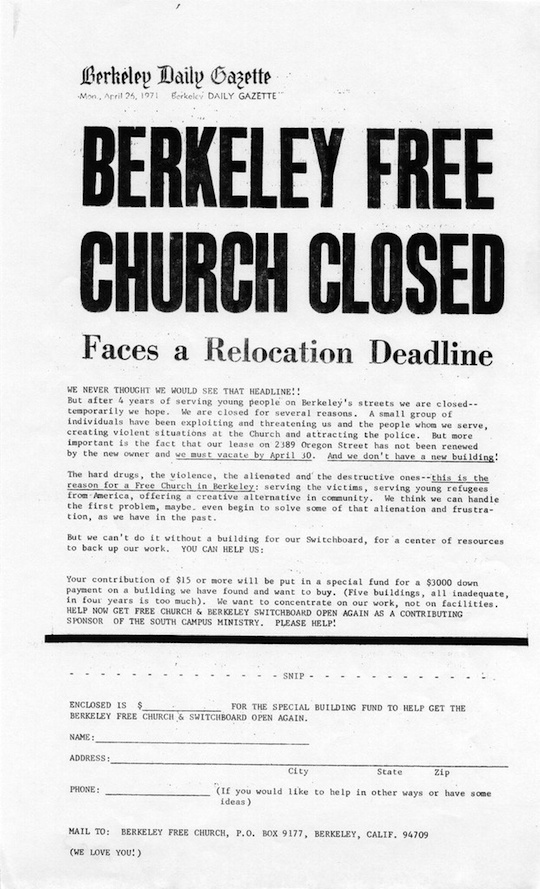

Richard York took a year off in 1972 and that was it. The Free Church of Berkeley was done, 1967-1972.

State

Telegraph pulsed with politics – street politics. Over the course of several years, it also pulsed with electoral politics a la Telegraph. In the end, a strong group of progressive politicians was elected to office in Berkeley, including Ron Dellums, Loni Hancock, and Tom Bates. I’m not talking about them. I am talking about the radicals who ran and lost.

The song to set the stage? Well, in the only song that I can conjure about that speaks to electoral politics, David Crosby warns “Don’t try to get yourself elected / because if you do, you’ll have to cut your hair.” That works:

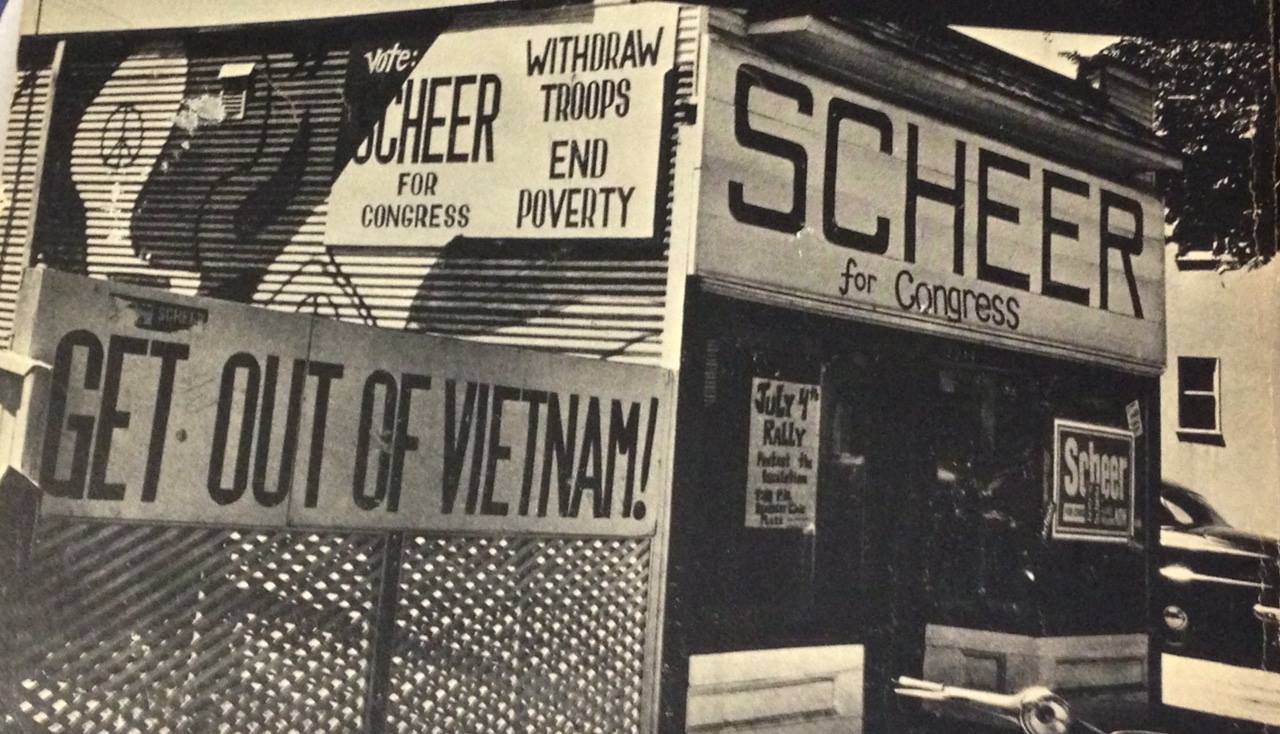

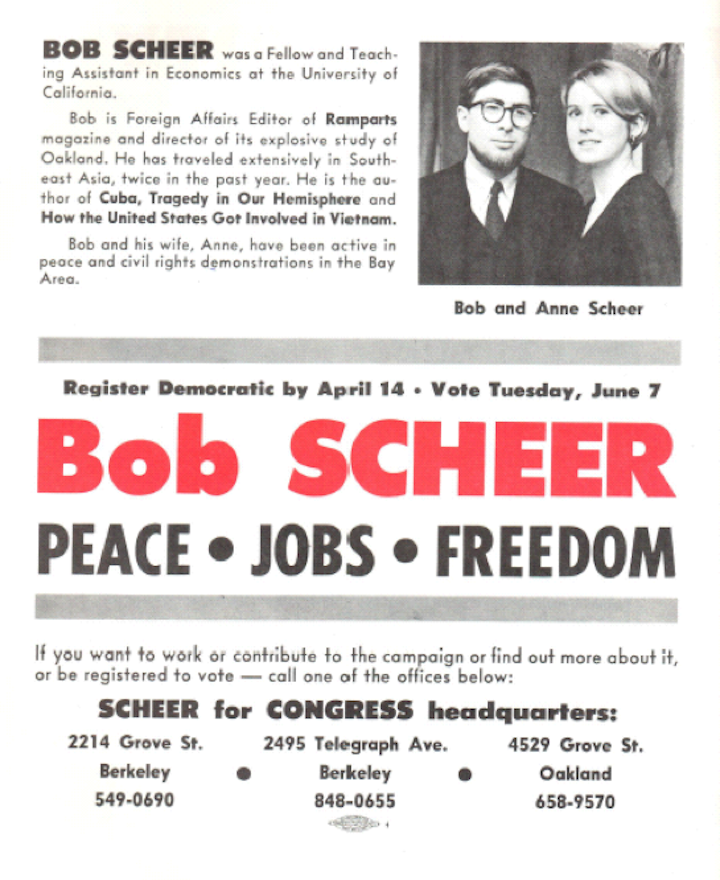

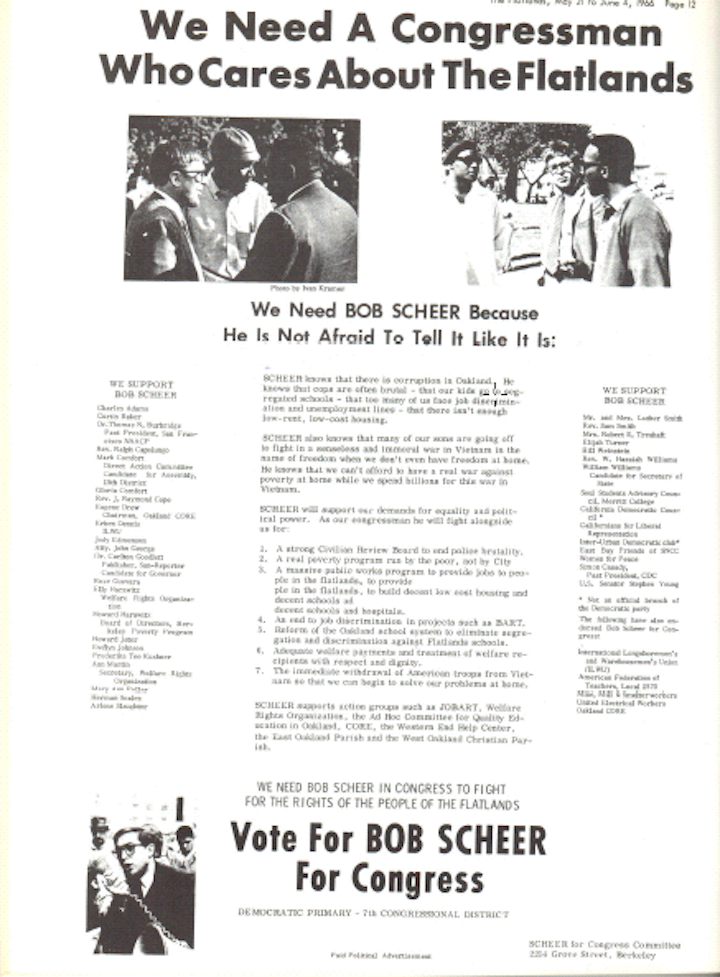

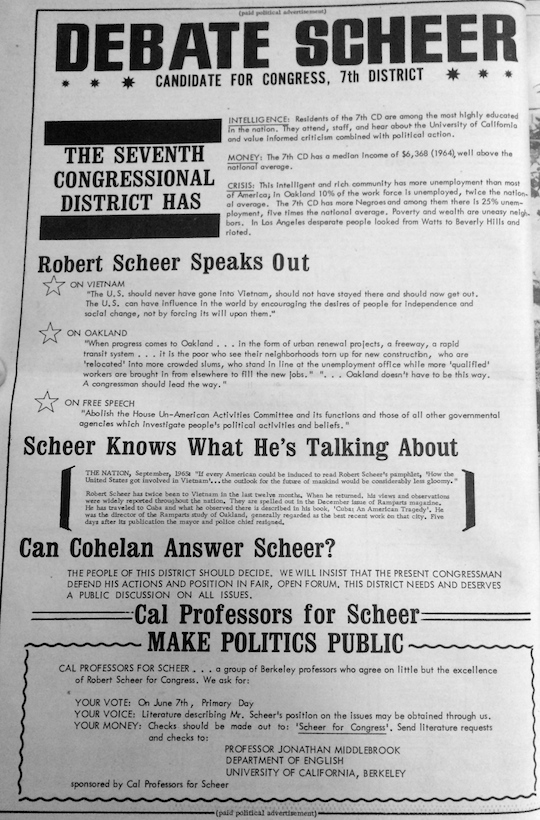

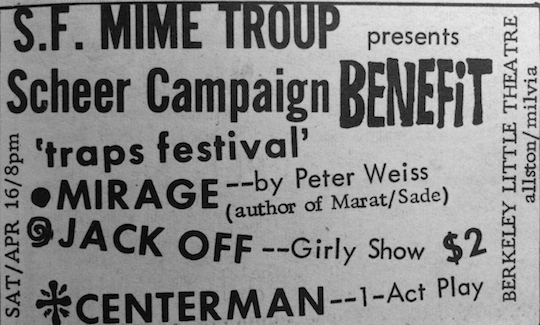

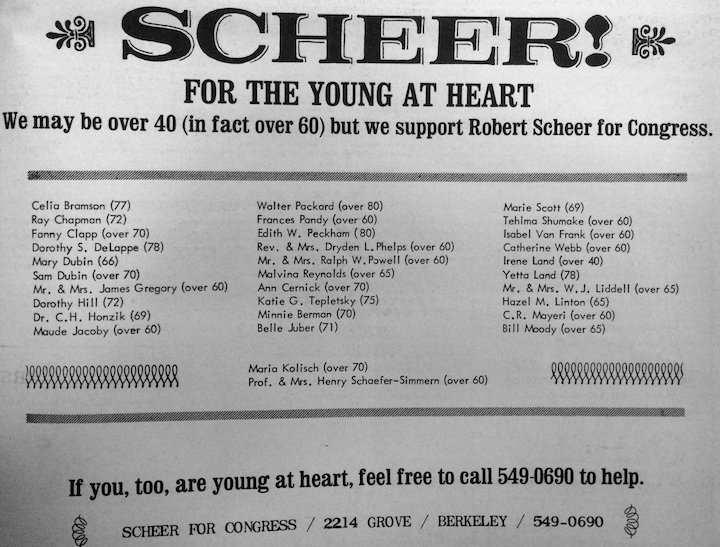

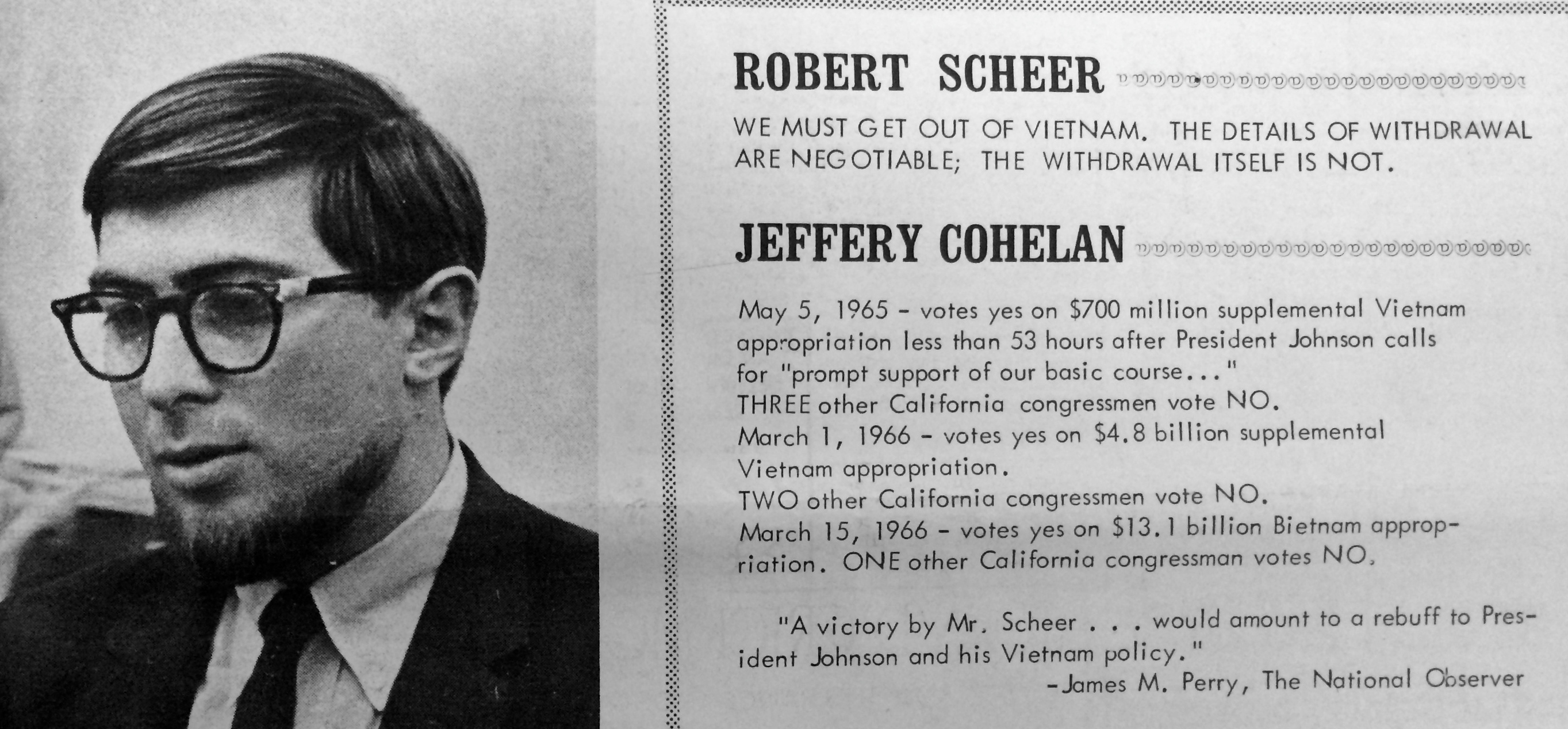

The first radical venture into electoral politics was the most serious – Robert Scheer’s 1966 primary challenge of Rep.Jeffrey Cohelan, an LBJ (pro-war) liberal who had served in the House since 1959.

Photo: http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt4x0nb0bf;NAAN=13030&doc.view=frames&chunk.id=d0e2400&toc.depth=1&toc.id=&brand=calisphere

In this photo Scheer is campaigning with Bob Treuhaft and Willie Brown.

Scheer campaigned on the war, poverty, and a new style of politics.

The mainstream press saw him as a definite threat to the status quo:

His campaign produced a prodigious amount of literature. He was all about issues, and he wrote and talked about them with intelligence and without pause.

These five ads were published in the Berkeley Citizen:

Scheer received 29,393 votes to Cohelan’s 35,921. He won the election in Berkeley, North Oakland, and West Oakland. Terming the results a “moral victory and political success,” Scheer clearly sent a message to pro-war Democrats. If Cohelan didn’t get the message right away, he did in 1972 when Ron Dellums defeated him in the primary and began his long career in the House.

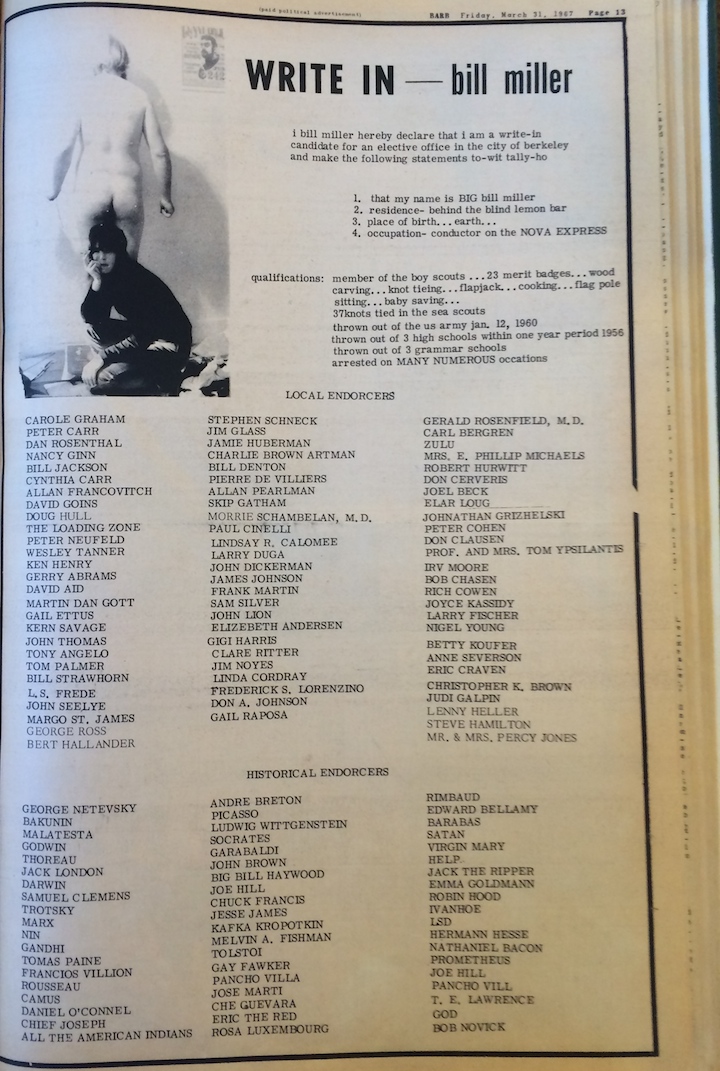

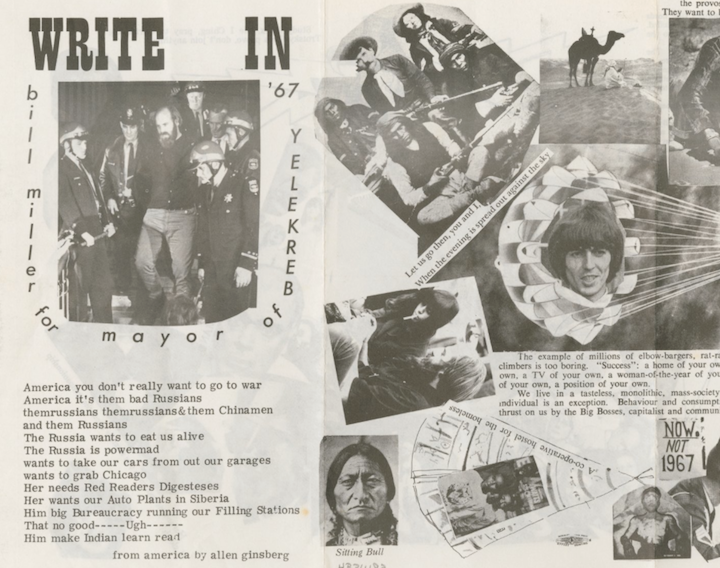

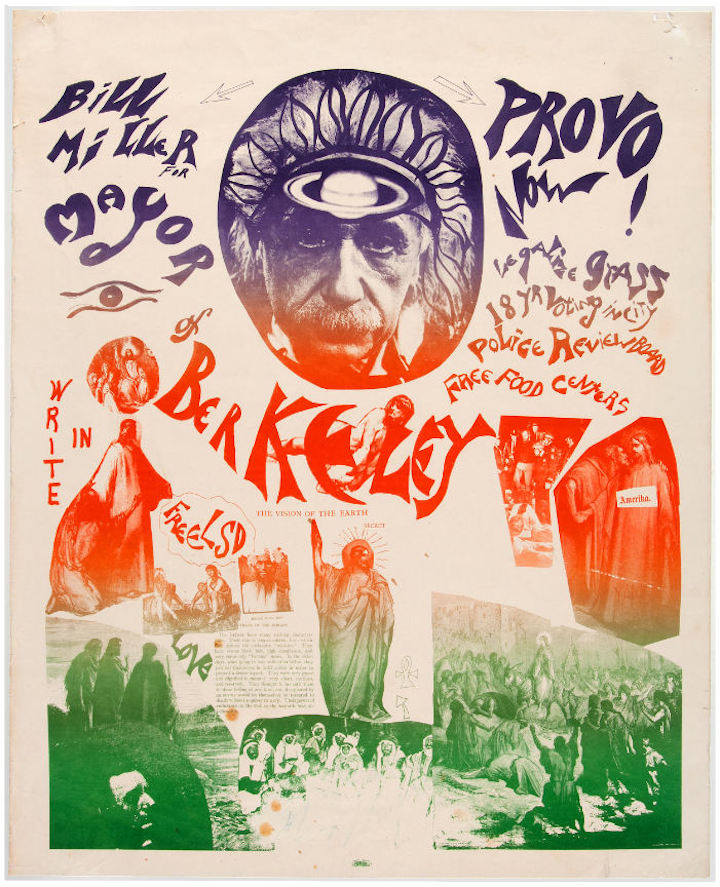

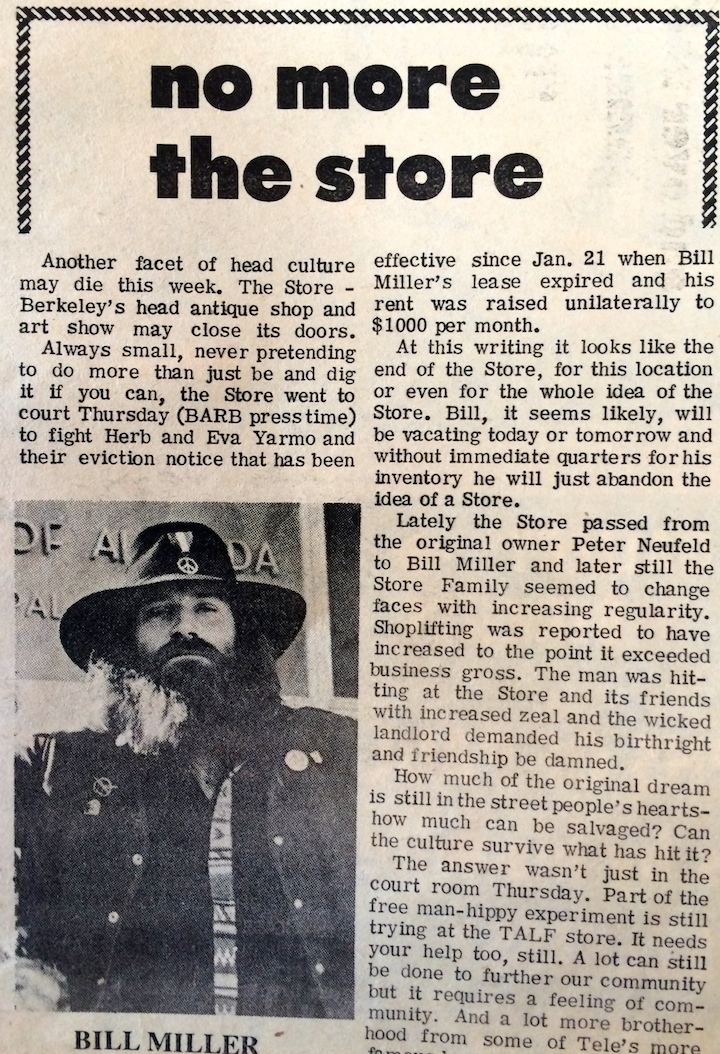

In 1967, two products of Telegraph Avenue ran for mayor of Berkeley, Jerry Rubin and Bill Miller. Let’s start with the more legitimately Telegraph of them, Miller.

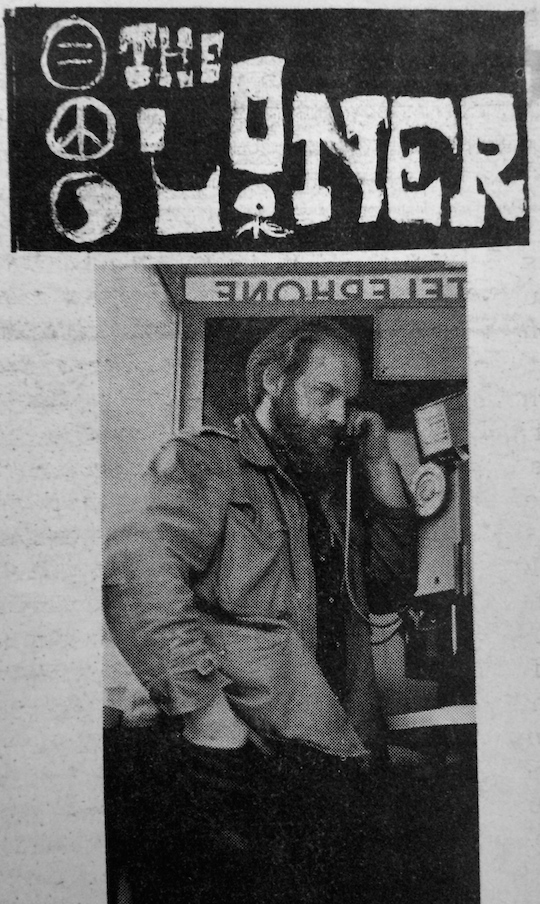

Bill Miller ran the General Store on Telegraph, a head shop. For several months in early 1967, he wrote a column for the Berkeley Citizen, a short-lived newspaper with left credentials, but well to the center of the Barb.

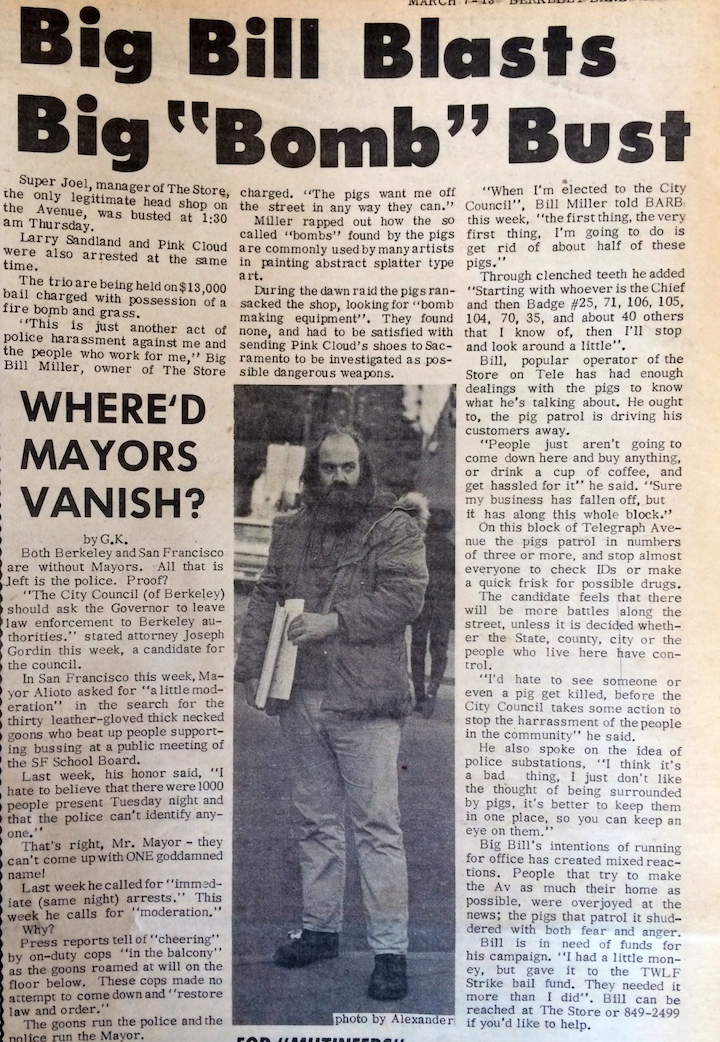

He was in and out of trouble with the police. Mostly in.

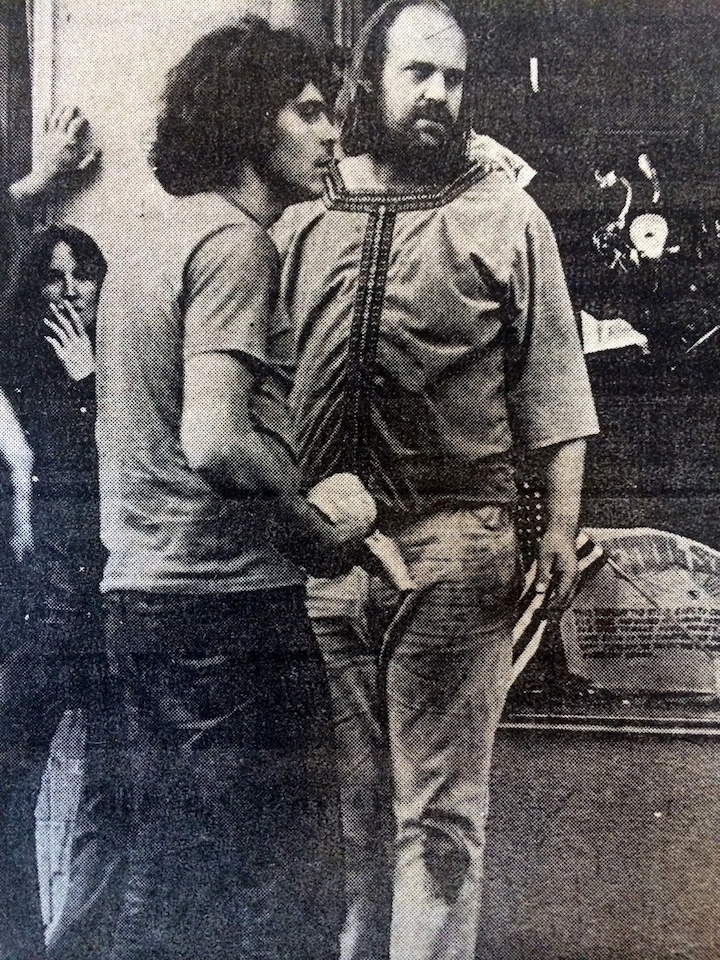

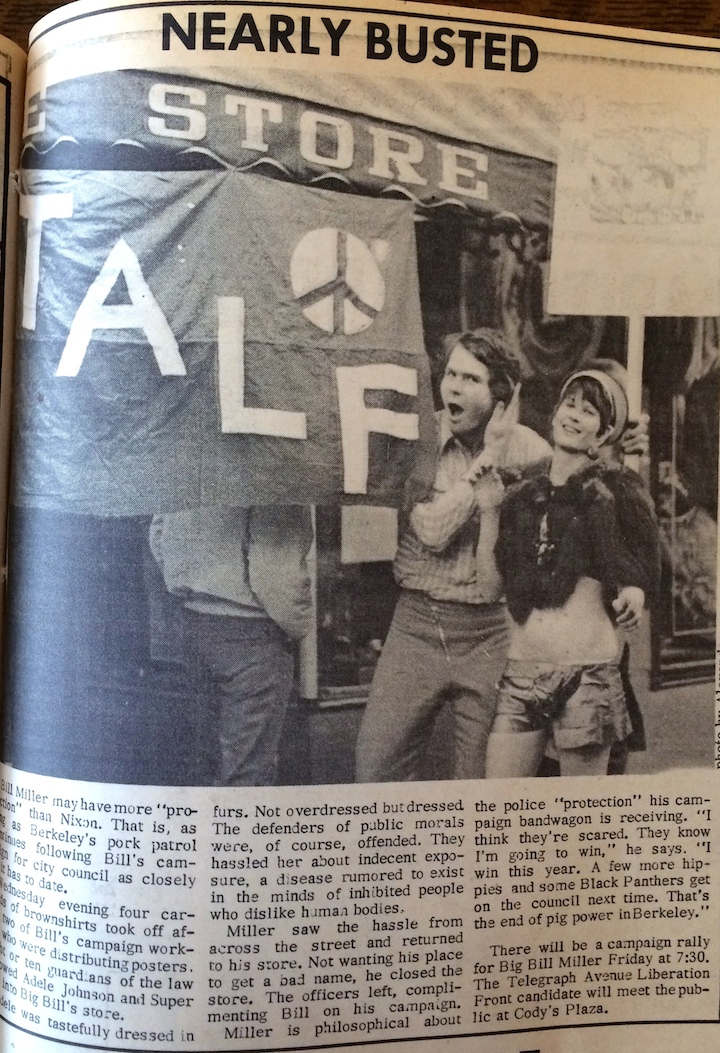

When he wasn’t in trouble himself, his store manager, Super Joel (shown here with a Telegraph Avenue Liberation Front flag), was.

When he wasn’t in trouble himself, his store manager, Super Joel (shown here with a Telegraph Avenue Liberation Front flag), was.

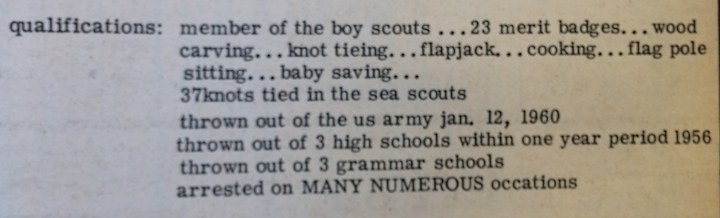

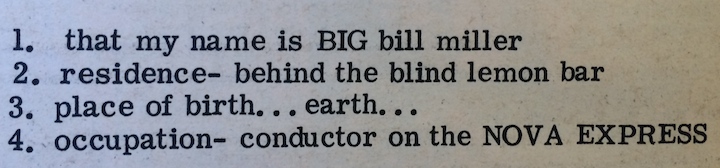

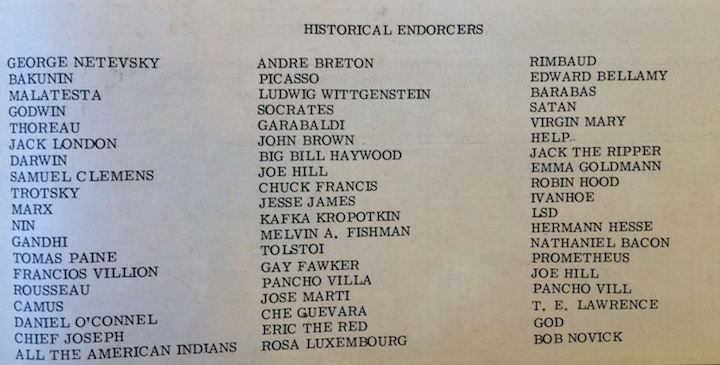

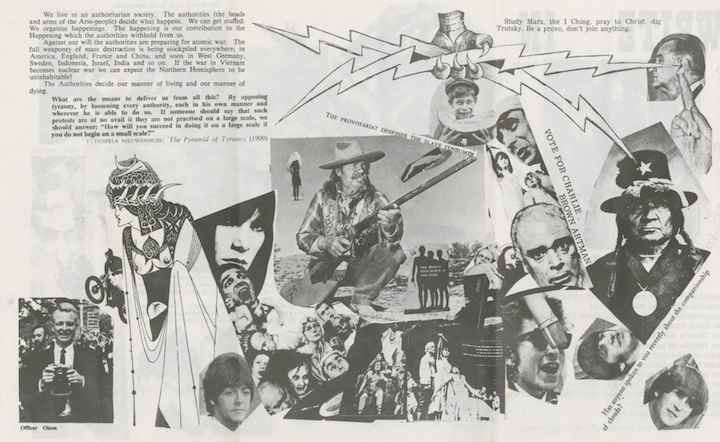

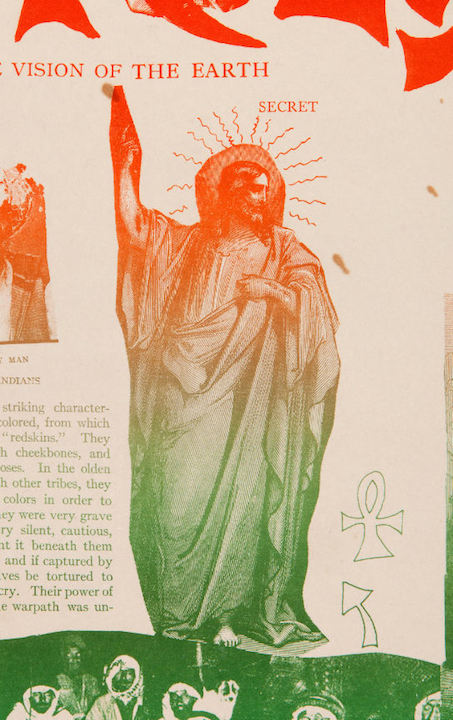

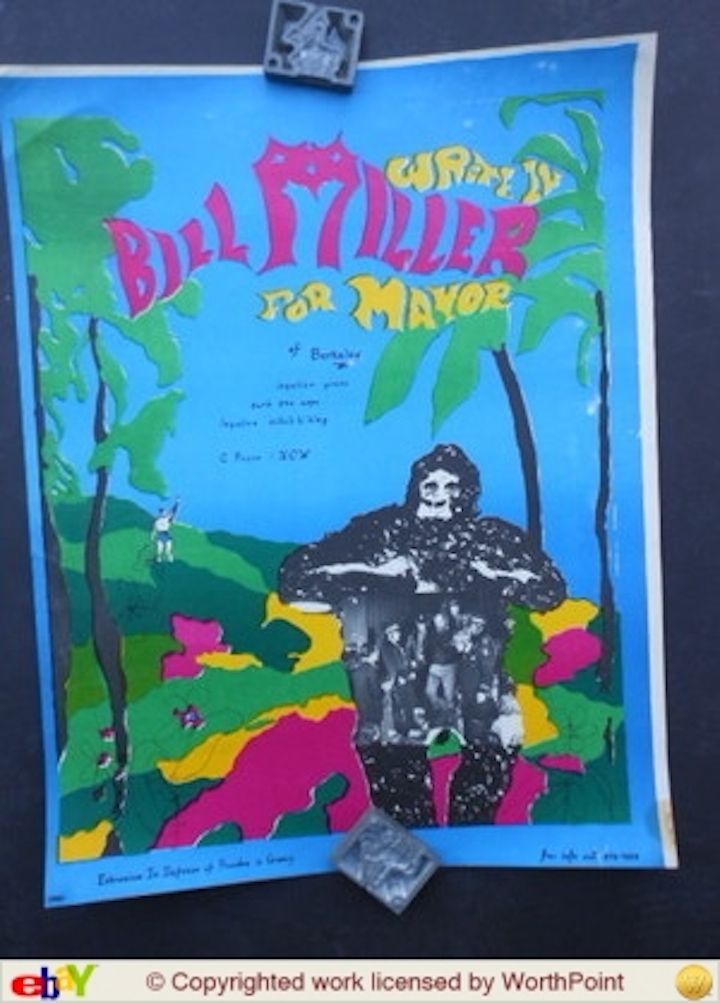

When Miller announced that he was running, he did so with tongue firmly in cheek. His campaign literature made his intentions clear.

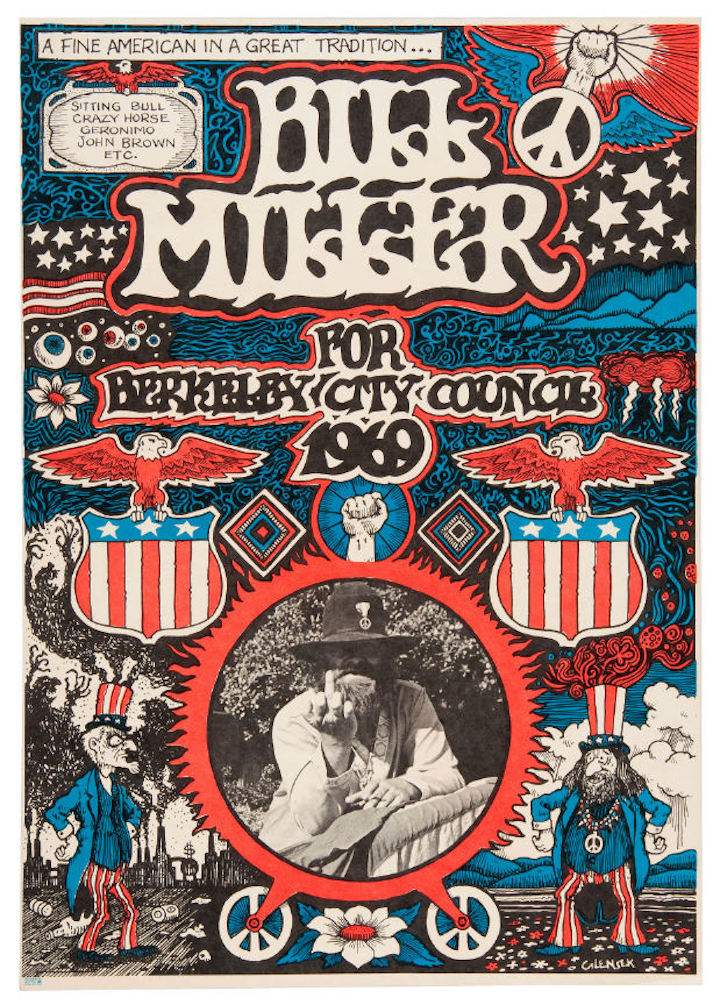

He advertised in the Barb, he produced leaflets, he produced posters.

He advertised in the Barb, he produced leaflets, he produced posters.

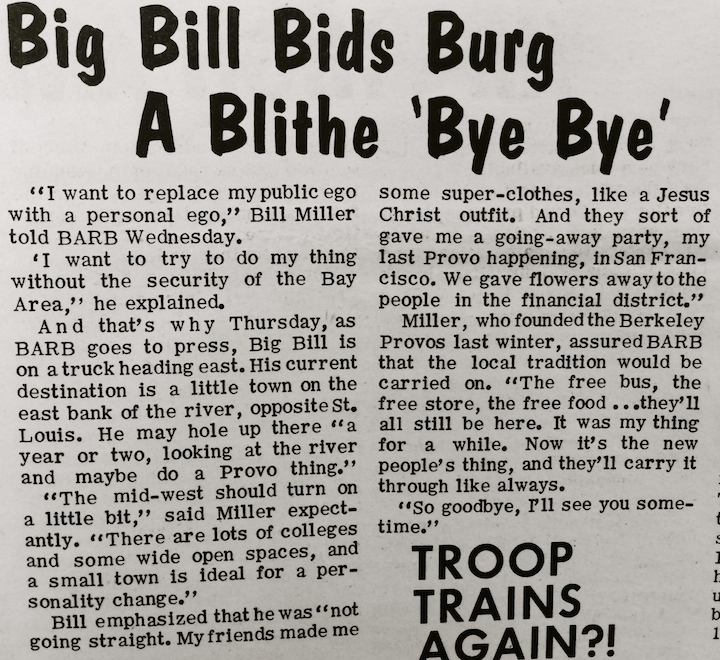

And as a result of all this work he got 61 votes. Out of 35,921. One tenth of one percent. He folded up and left.

And as a result of all this work he got 61 votes. Out of 35,921. One tenth of one percent. He folded up and left.

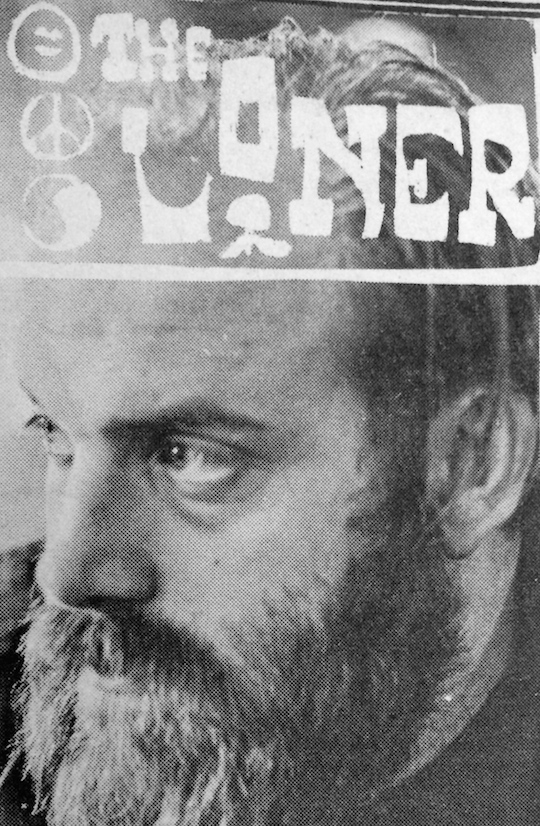

By 1969, Miller was back in Berkeley. He ran the Steppenwolf bar at 2136 San Pablo, which had once been owned by Max Scherr of Berkeley Barb fame. He ran for City Council in 1969.

By 1969, Miller was back in Berkeley. He ran the Steppenwolf bar at 2136 San Pablo, which had once been owned by Max Scherr of Berkeley Barb fame. He ran for City Council in 1969.

He improved substantially from his 1967 race, winning 2,548 votes, or 2.2% of the votes cast.

This account of the founding of People’s Park mentions Miller prominently: “The other two important park planners, Big Bill Miller and Super Joel Tornabene, were members of Stew Albert’s hip-radical fusion. Miller had been active in the Berkeley student movement since FSM days, during which he was convicted of trespassing and resisting arrest for his role in the December 2, 1964, Sproul Hall sit-in, fined $150, and given a one-year probation. He quickly became involved with the VDC and in 1966 was arrested twice with Albert–initially for an April antiwar march from Telegraph Avenue to City Hall and later for a November sit-in at the student union in protest of the university’s consent to use of the facility for naval recruitment while refusing permission to the VDC. On the hip side of the hip-radical fusion, Miller owned The Store, a Telegraph Avenue business that specialized in selling drug paraphernalia. In April 1969, he campaigned as a Yippie-style candidate for the Berkeley City Council with an election slogan designed to appeal to the drug culture: “To get a head, you have to vote for a head.”

In 1984, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Miller was living in Monte Rio. He eventually moved to New Mexico, where he set up shop as an honest-to-goodness Indian trader. Trading stuff.

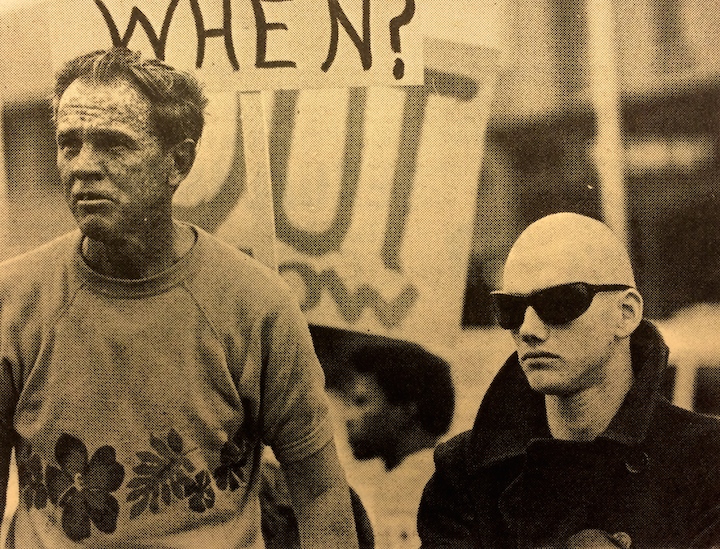

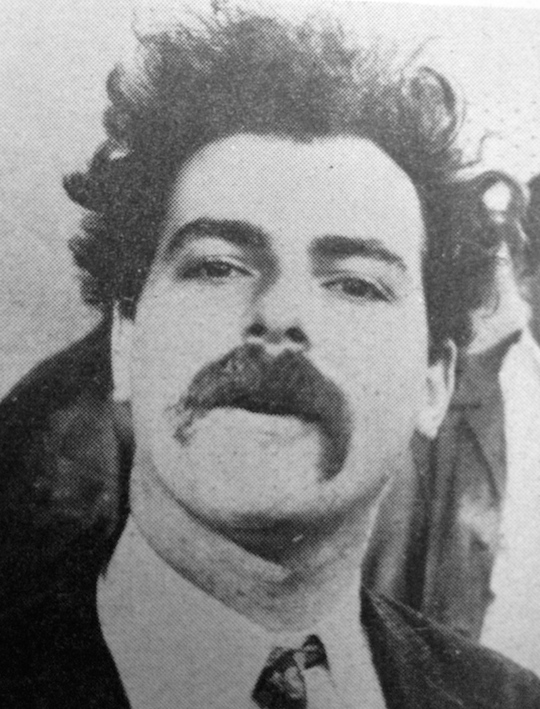

The second radical candidate for mayor in 1967 was Jerry Rubin. Rubin had come to national attention as a leader of the Vietnam Day Committe, a very early anti-war group. He is on the right of this photo, which was taken in October 1965 at an anti-war rally.

Although Rubin was for a while from Berkeley, he doesn’t seem to me, all these years later, to have been an authentic product of Berkeley.

This photo shows him at Dwight and Telegraph. What a difference a few years made! He was here, but was he really one of us? Some would say he was. Not so sure.

This photo shows him at Dwight and Telegraph. What a difference a few years made! He was here, but was he really one of us? Some would say he was. Not so sure.

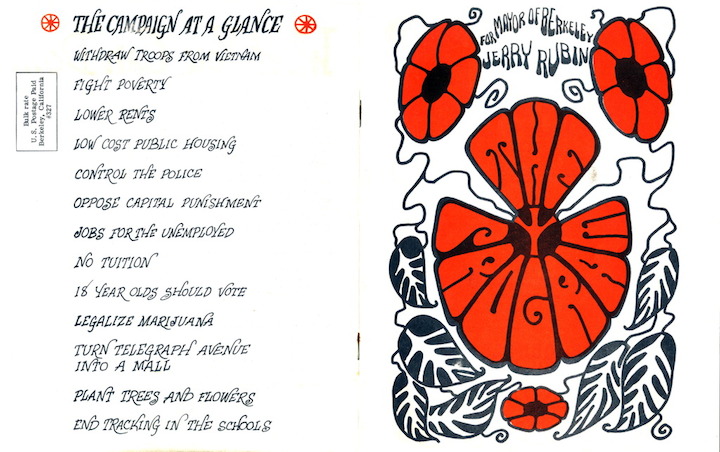

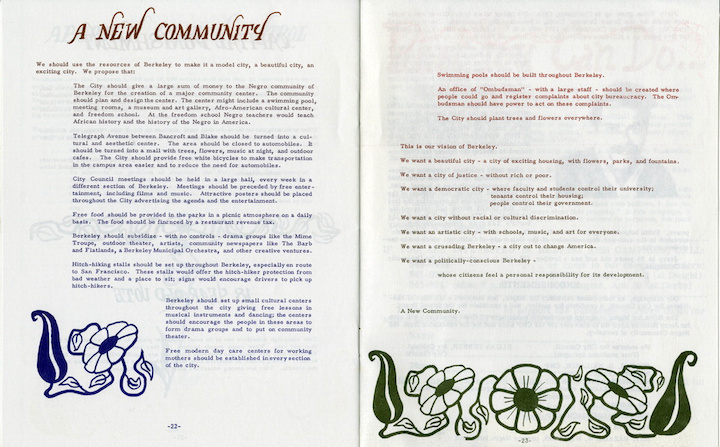

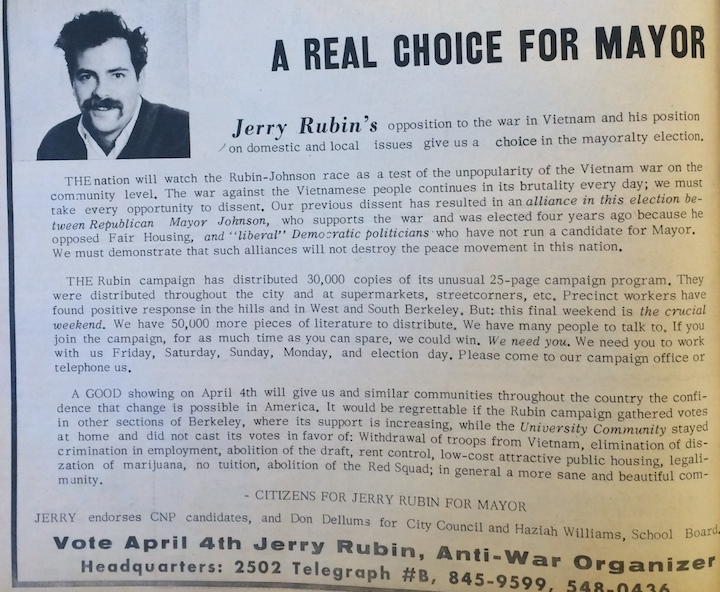

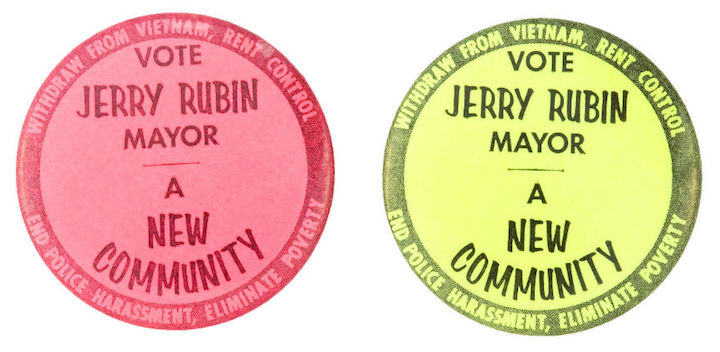

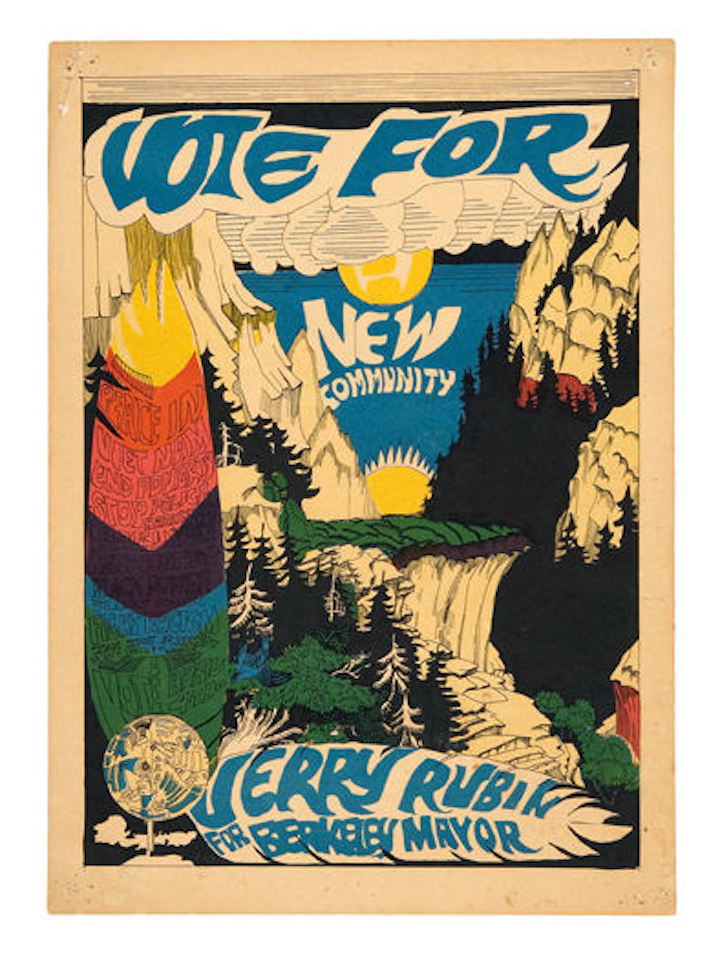

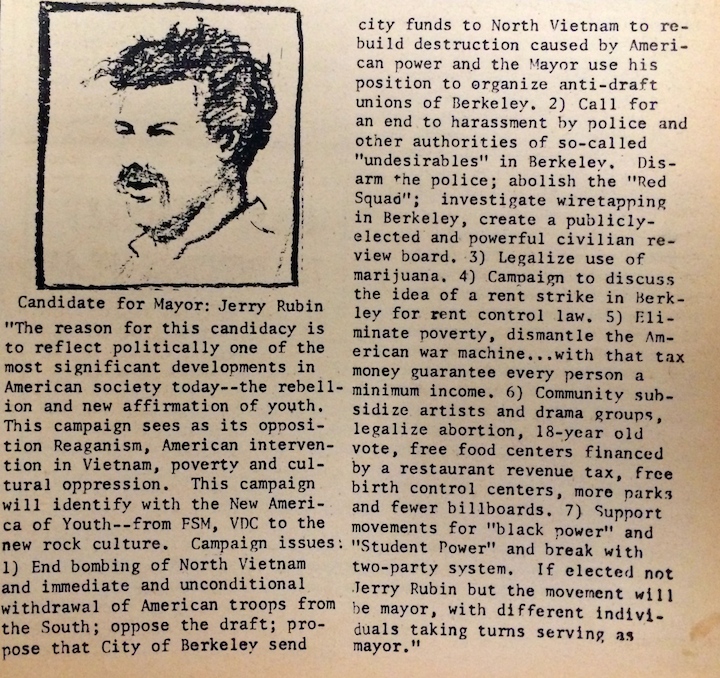

In any event, he ran for mayor. He produced literature. He produced buttons. He produced a killer psychelic poster.

Rubin famously ran on a platform in which he ventured that if he won, he could grant himself a pardon.

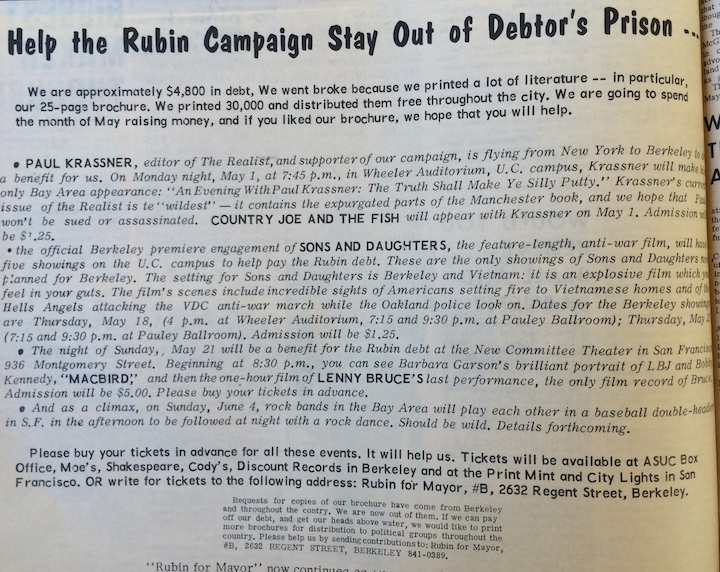

In the end, he did better than Bill Miller, winning 7,385 votes or slightly more than 20% of the vote. Not bad for a crazed hippie who was about to become a yippie. He had campaign debt to deal with, and the Barb jumped to his defense.

Shortly after the election he moved to New York and continued his mischief there.

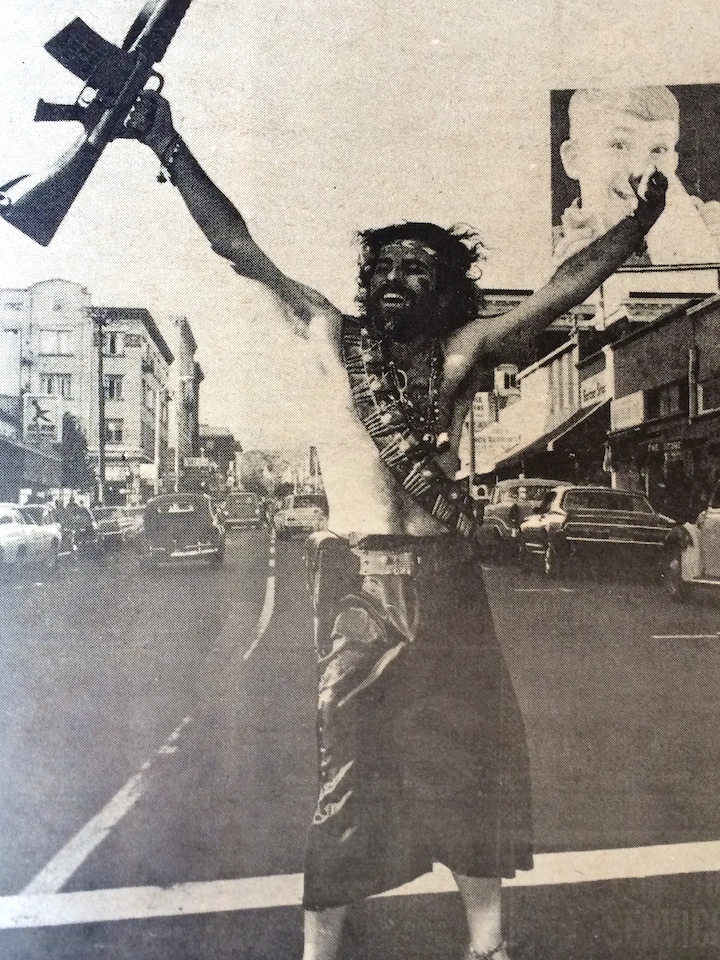

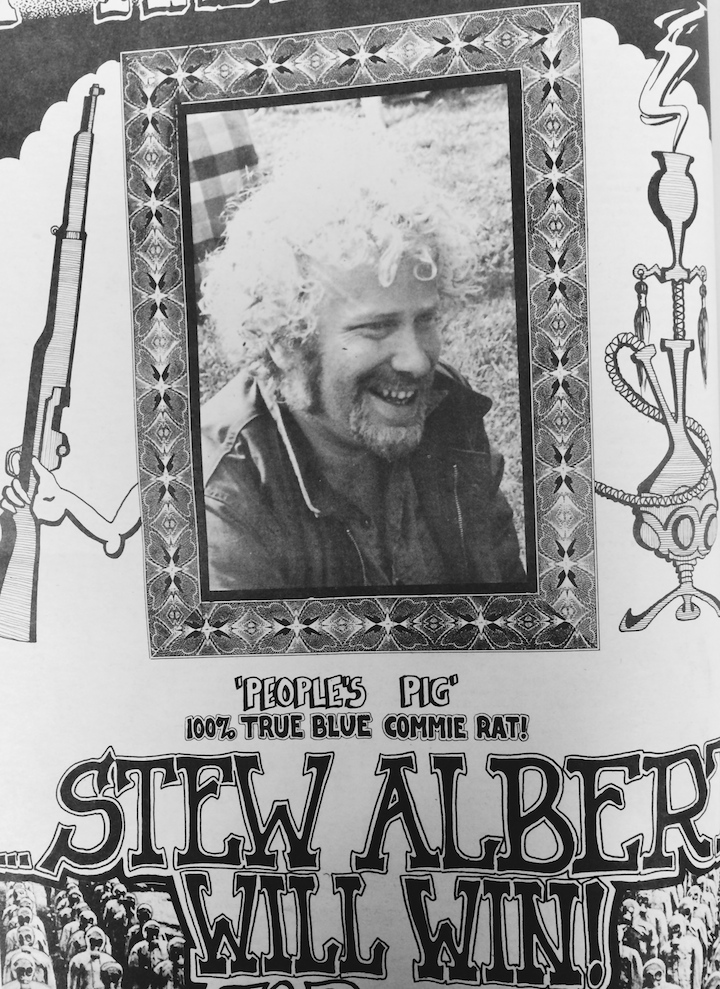

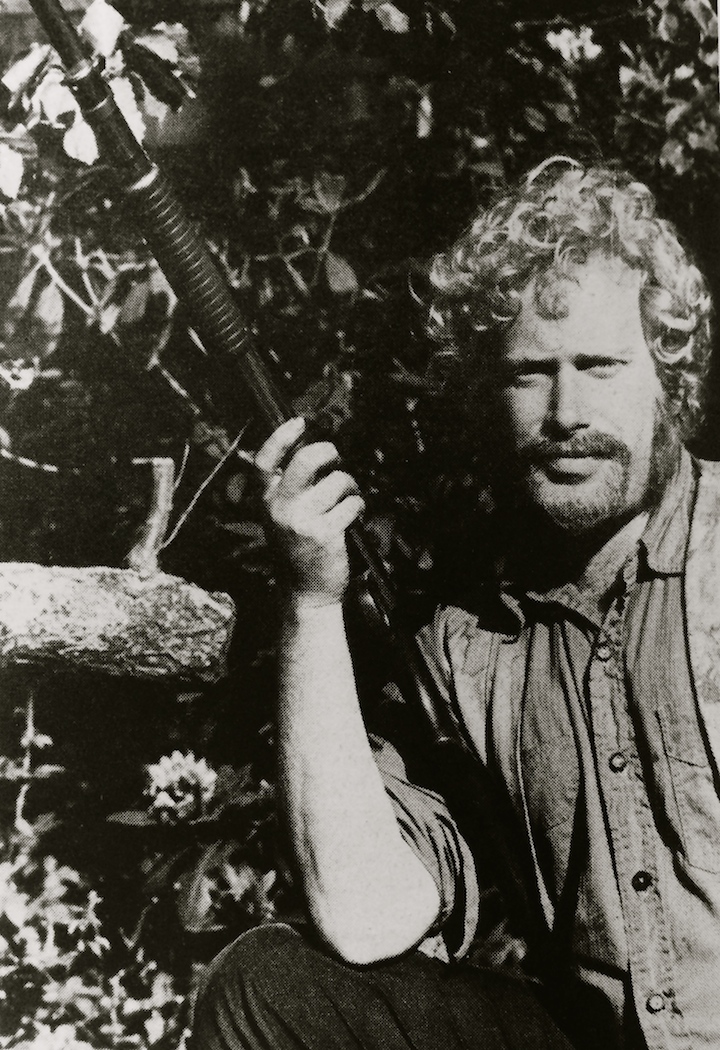

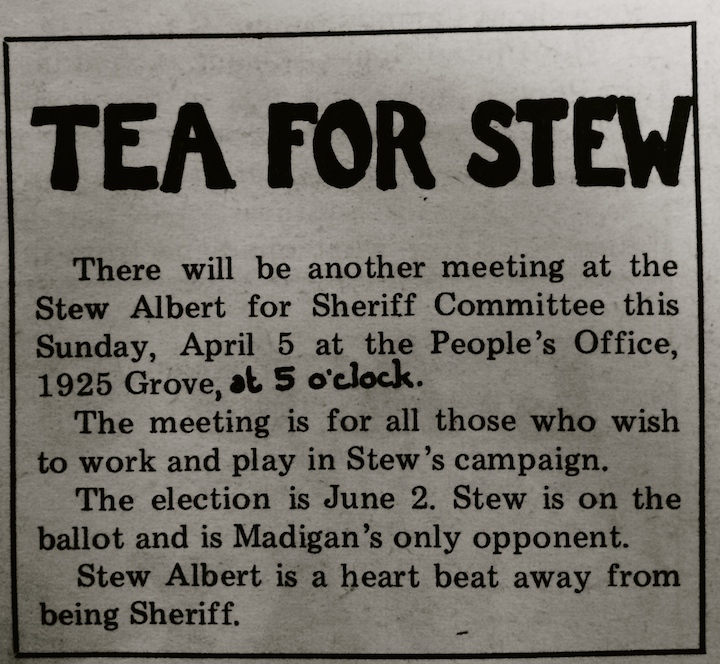

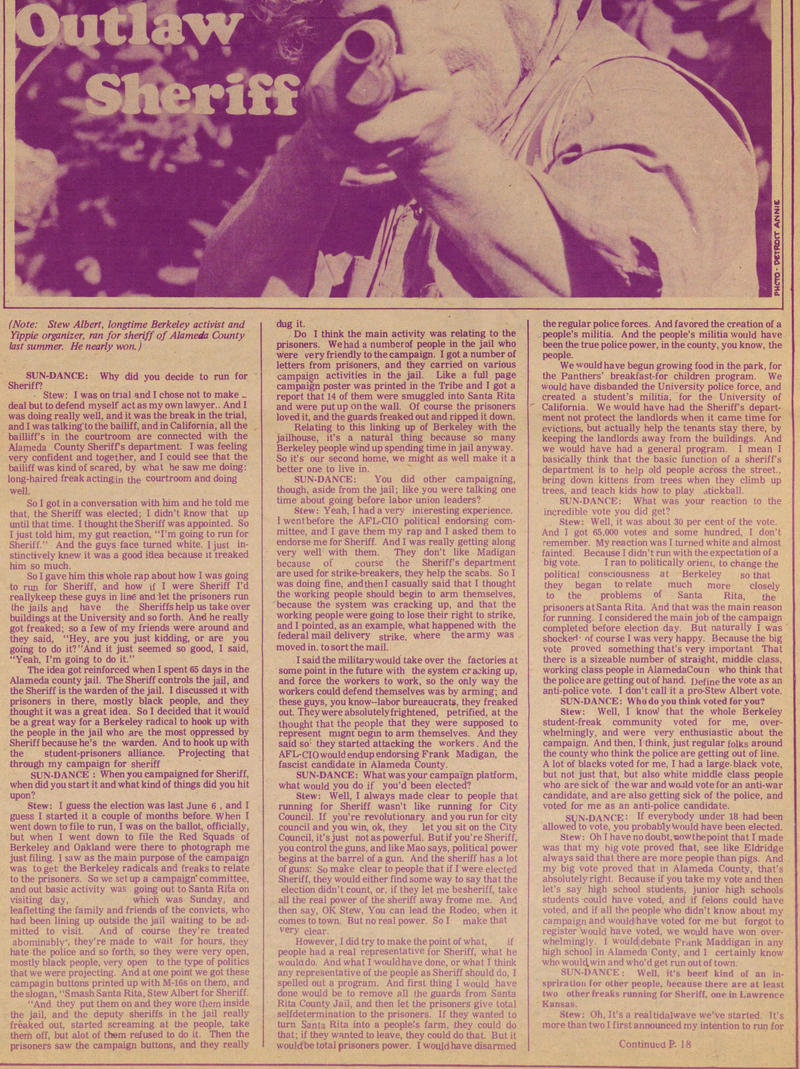

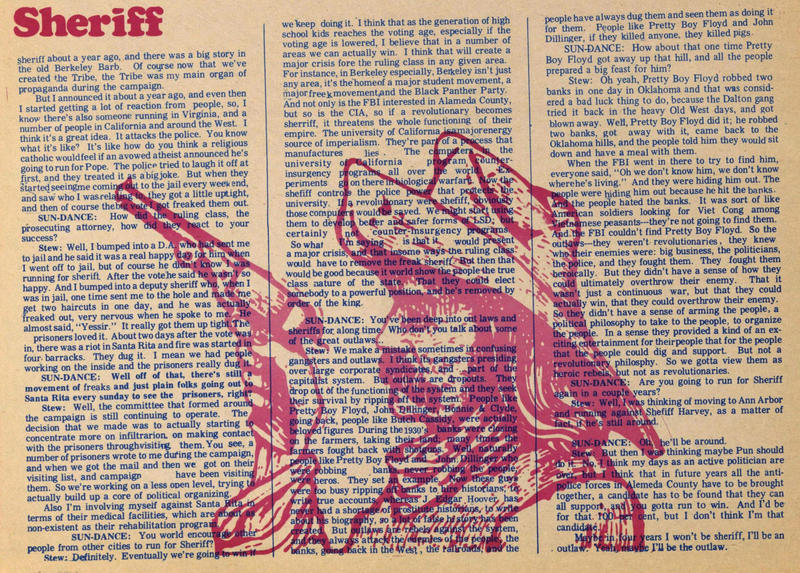

Last and not least, in 1970 a true son of Telegraph, Stew Albert, ran for Sheriff of Alameda against Frank Madigan. Madigan had been Sheriff since 1963 and played an important role in the law enforcement suppression of Telegraph Avenue.

Albert was closely associated with the Red Mountain Tribe, the colletive that published the Berkeley Tribe, and he embraced their militant position on armed self-defense. He was a Yippie and ran with Jerry Rubin (to his right in the Sinclair photo), Abbie Hoffman, and Super Joel. Albert was a central player in building People’s Park, and was a master of the issue is not the issue.

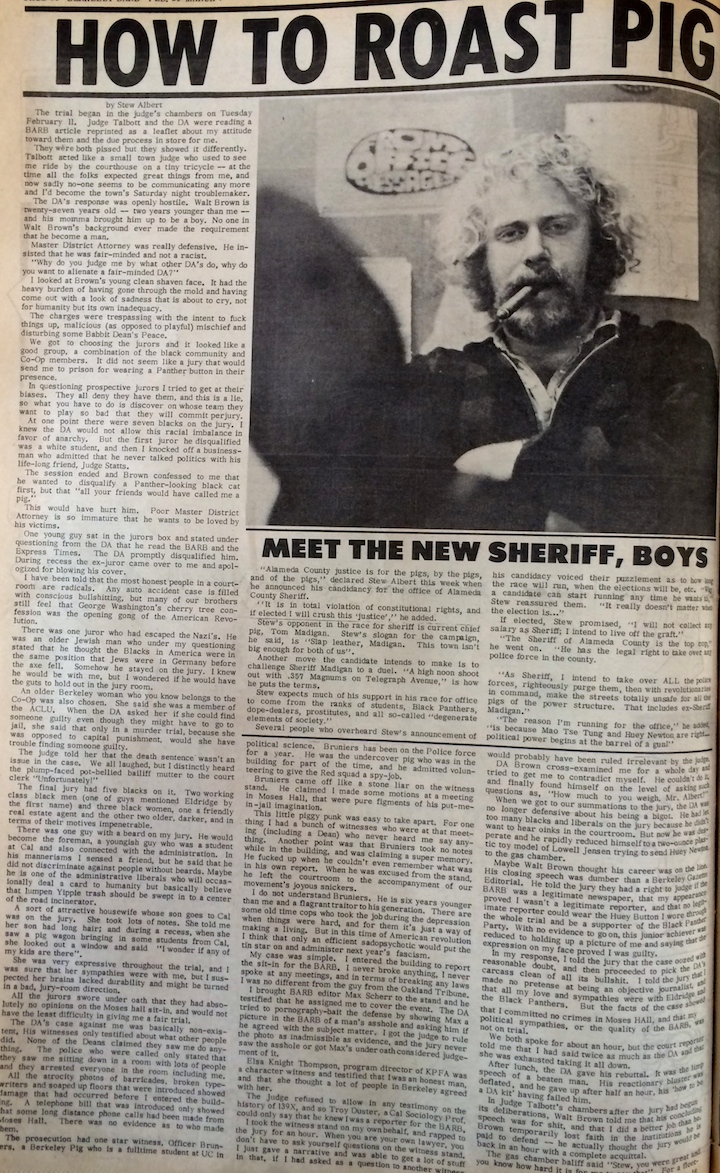

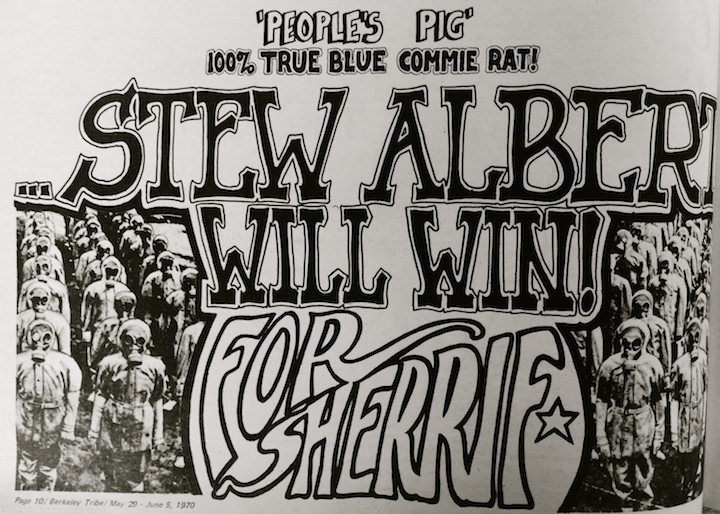

His 1970 campaign for Sheriff was the typical Yippie blend – part prank, part oh-so serious politics.

Do you think that spelling sheriff “sherrif” was intentional? It’s a tough word to spell, I know.

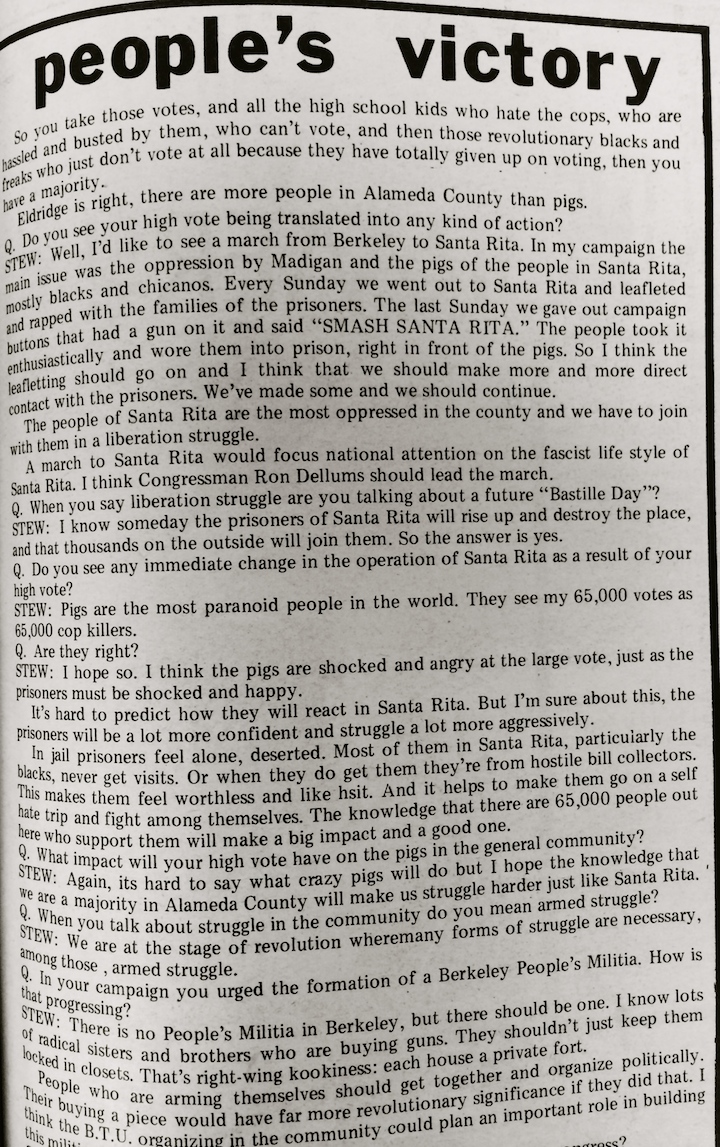

In the end, the People’s Pig won 65,000 votes, almost ten times as many votes as Jerry Rubin had received three years earlier when he ran for mayor of Berkeley. Albert declared it a moral victory:

In the end, the People’s Pig won 65,000 votes, almost ten times as many votes as Jerry Rubin had received three years earlier when he ran for mayor of Berkeley. Albert declared it a moral victory:

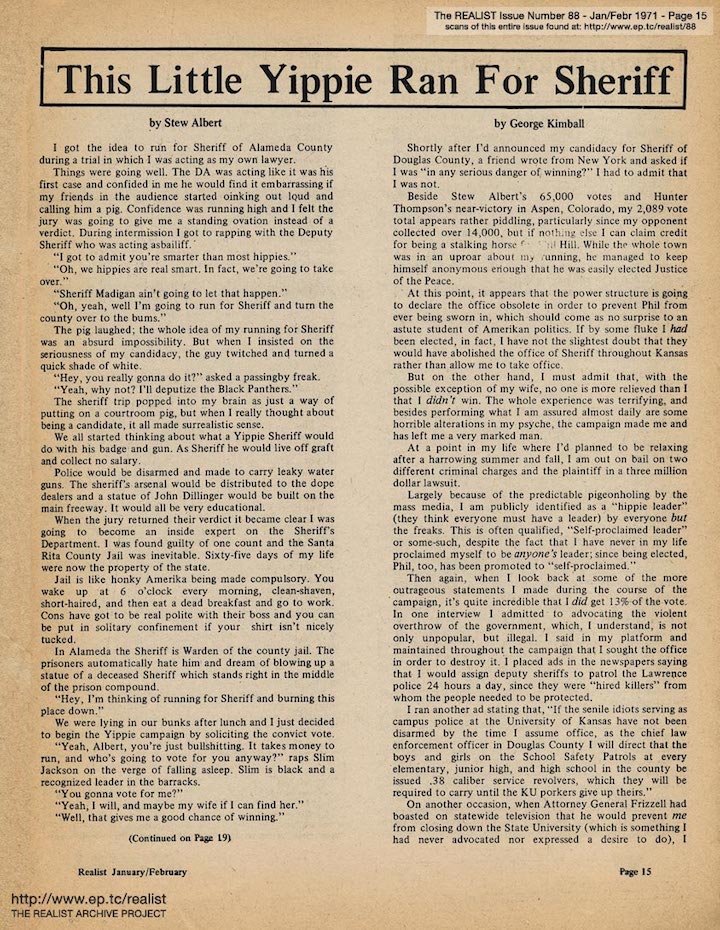

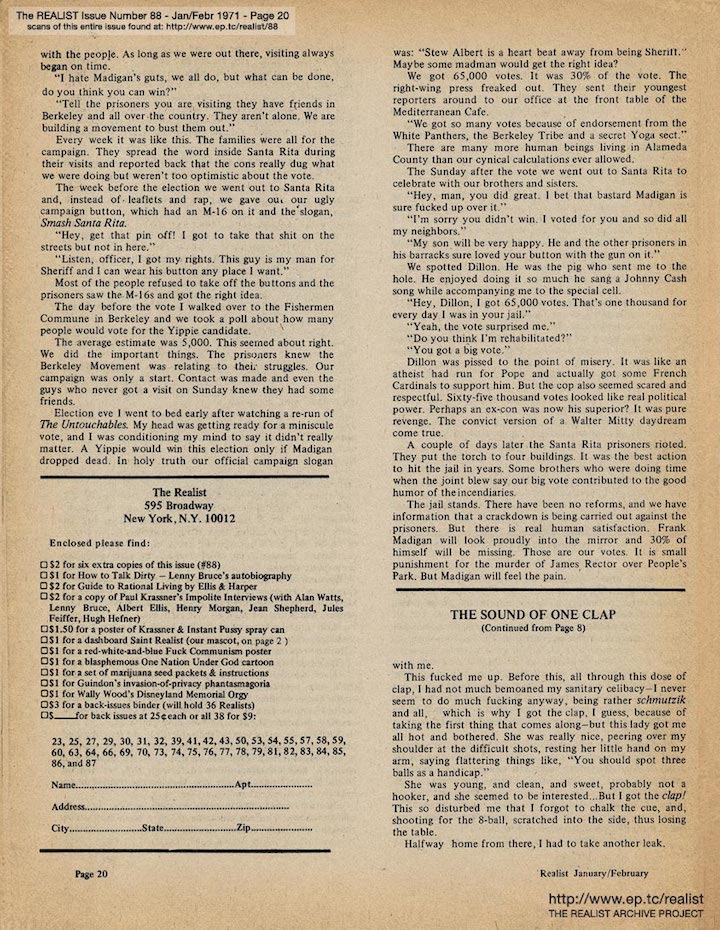

He wrote about his campaign in the Realist:

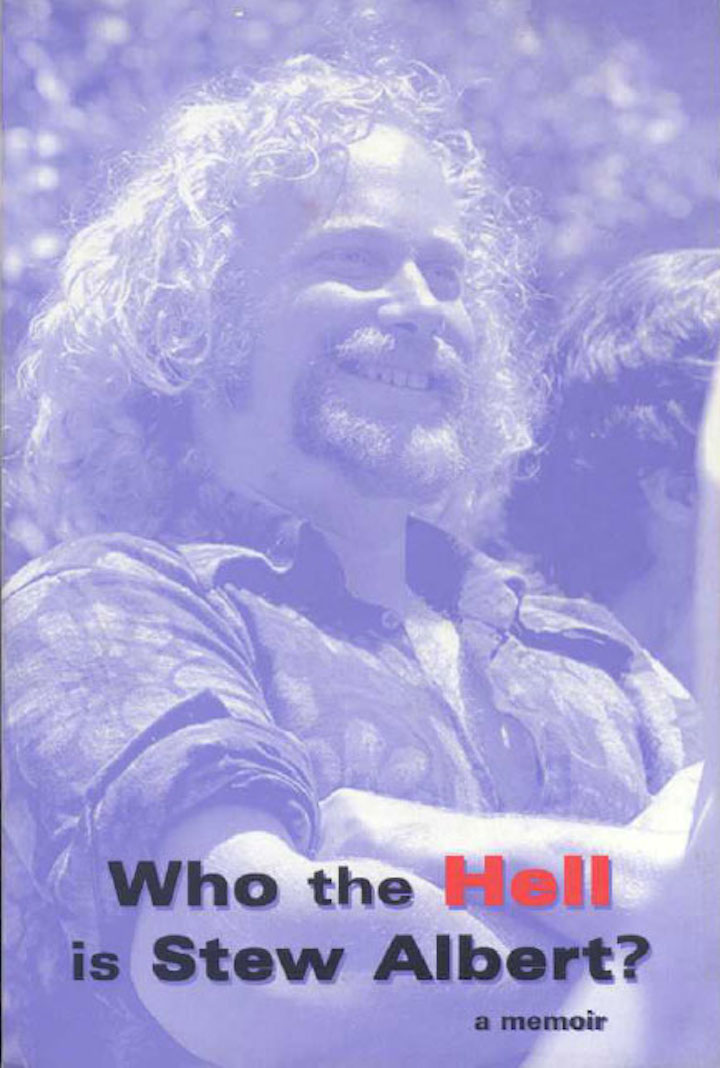

Shortly before his death he published a memoir of his unrepentant yippie life and beliefs.

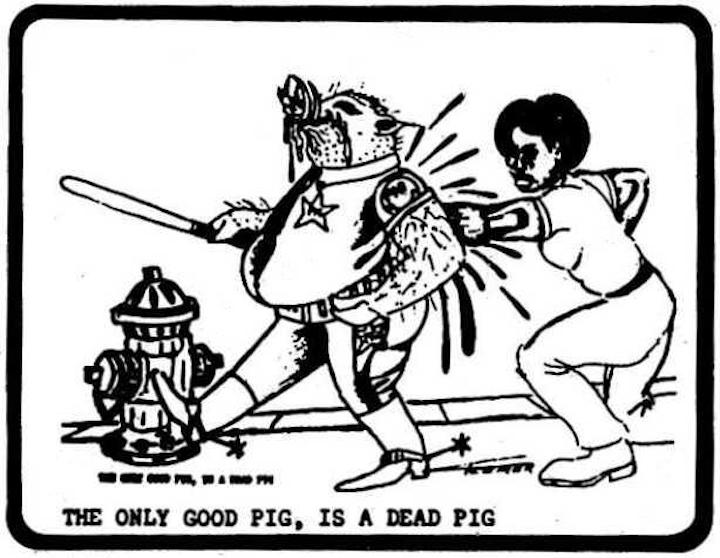

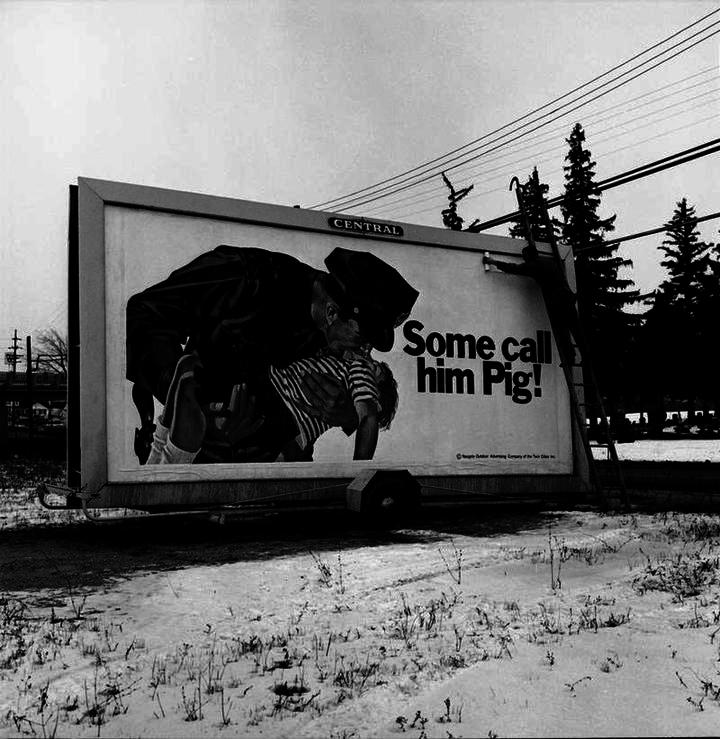

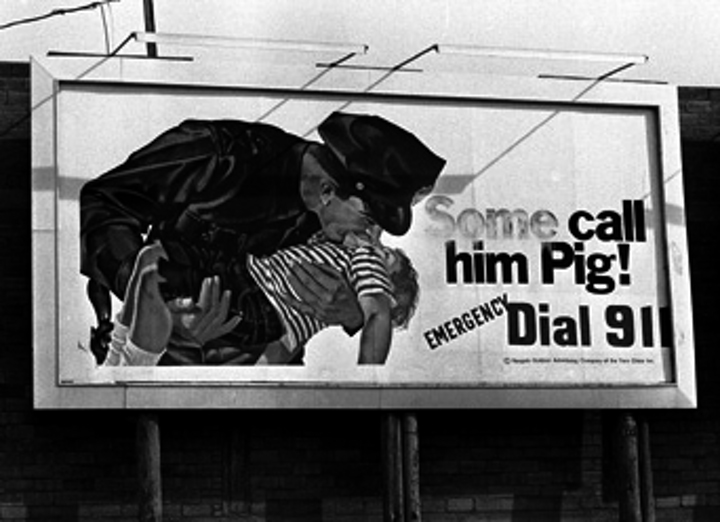

When I showed these photos to my friend, he zeroed in on Albert’s claim to be the “People’s Pig.” In 1971, my friend was living in Oakland. On one wall of his living room he had a huge blow-up of this Black Panther cartoon:

On the facing wall he had a collage made from 36″ by 48# blow-ups of photos of these billboards:

On the facing wall he had a collage made from 36″ by 48# blow-ups of photos of these billboards:

He amused himself and pulled out a photo of that living room. I steered him back to Church and State on old weird Telegraph. What did he think of Holy Hubert and Dick York and Bob Scheer and Big Bill Miller and Jerry Rubin and Stew Albert?

does anyone know where I can find a photo image of the original berkeley provo bus (1967)?

Pingback: John Pairman Brown – The Liberated Zone (1969) | 1960s: Days of Rage

Anyone remember Pedro?