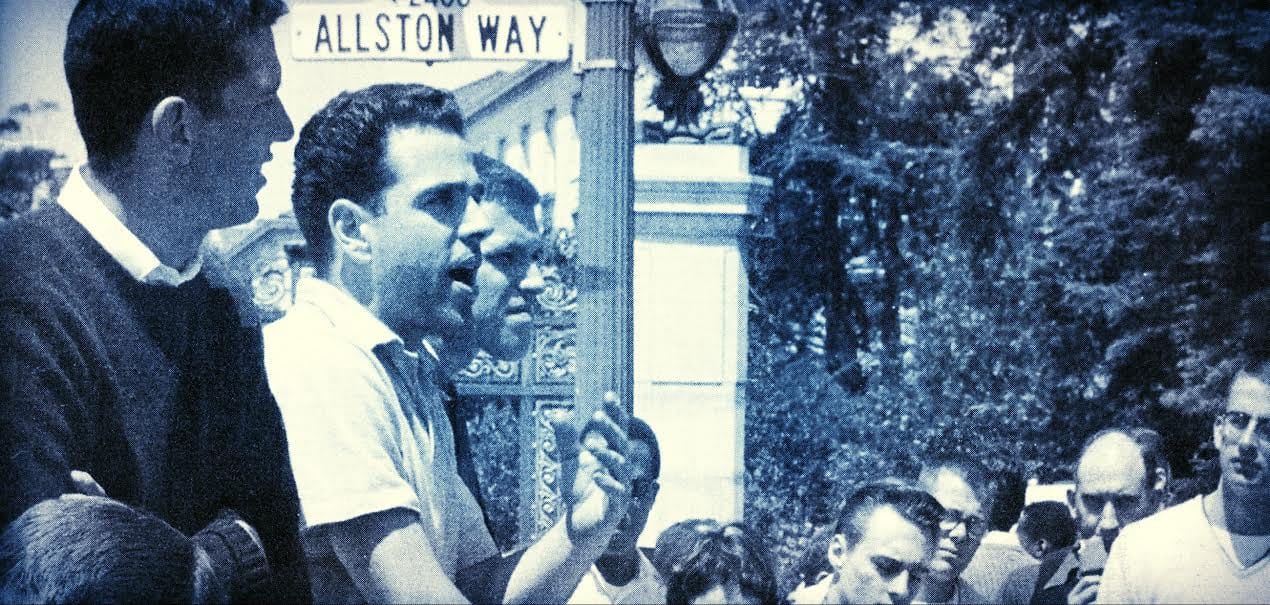

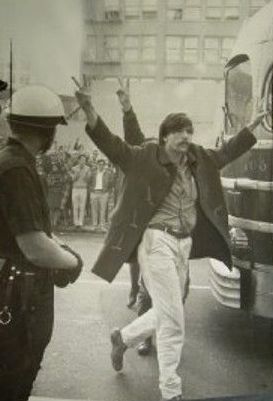

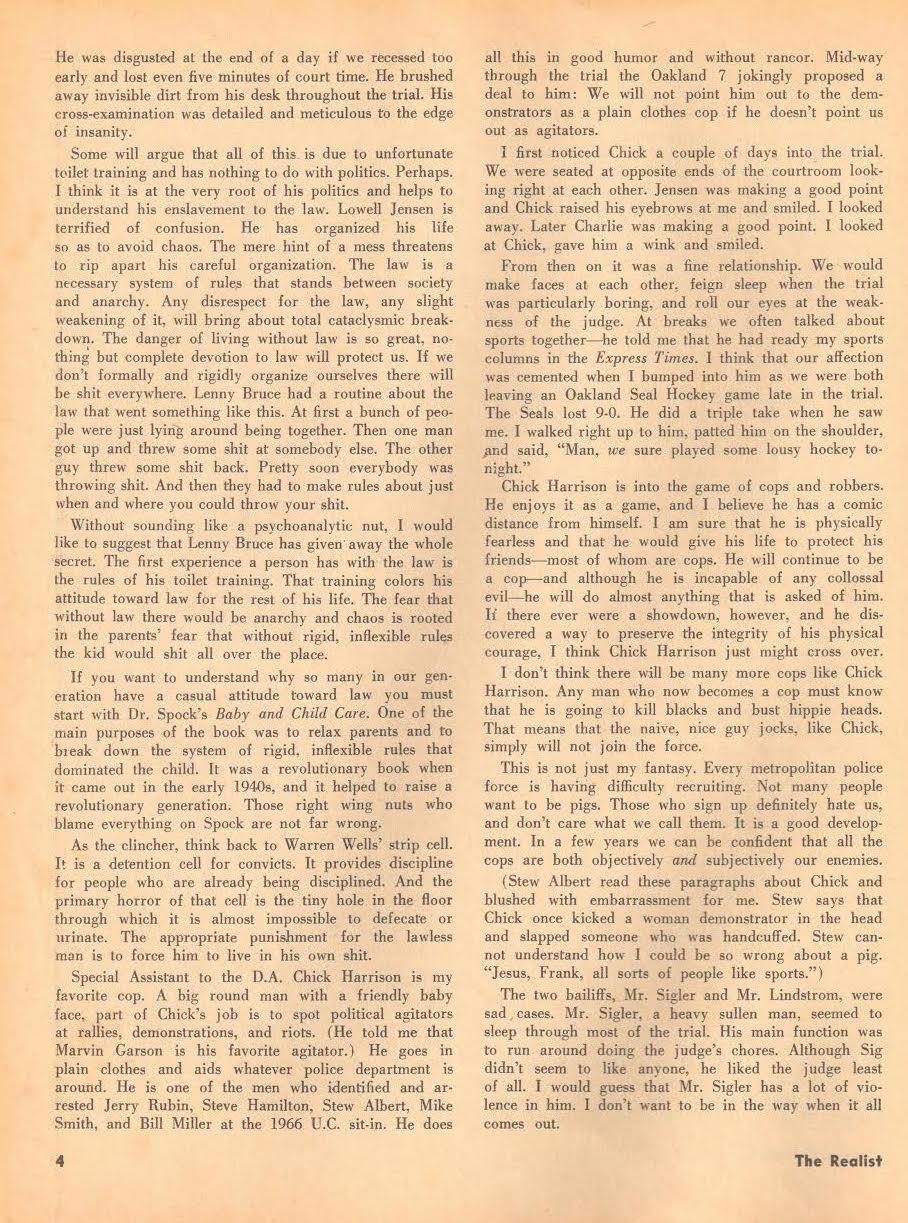

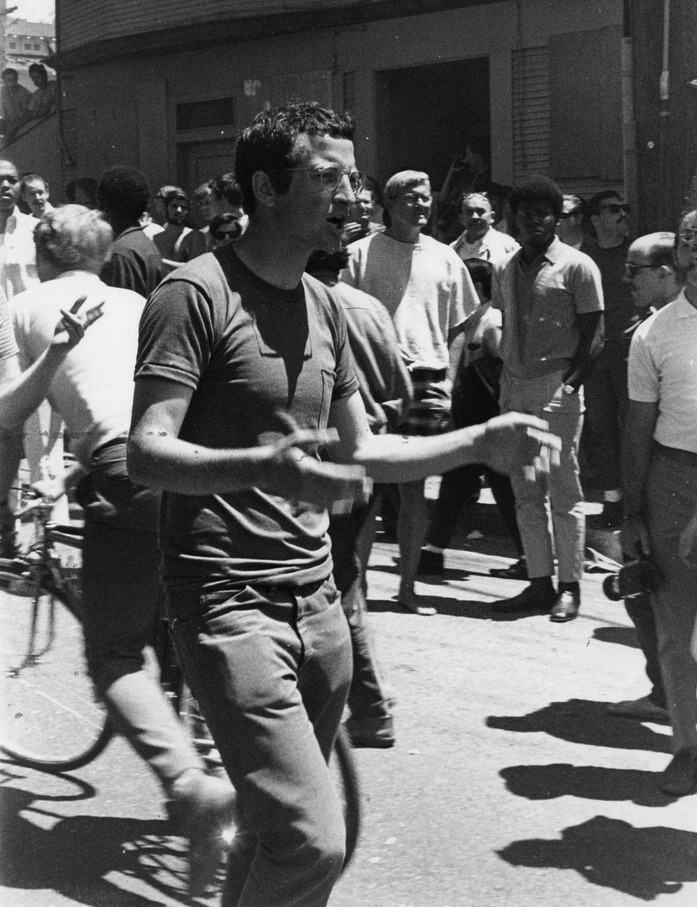

A lone demonstrator stays behind to argue with the National Guards troops who moved in to help California Highway patrolmen break up an unauthorized rally on the University of California Campus in Berkeley, Ca., Friday, May 16, 1969. The guard was called by Gov. Ronald Reagan Thursday after a bloody riot over the fencing of People’s Park, which had been built on school property. Several persons were shot when police opened fire with shotguns. (AP Photo)

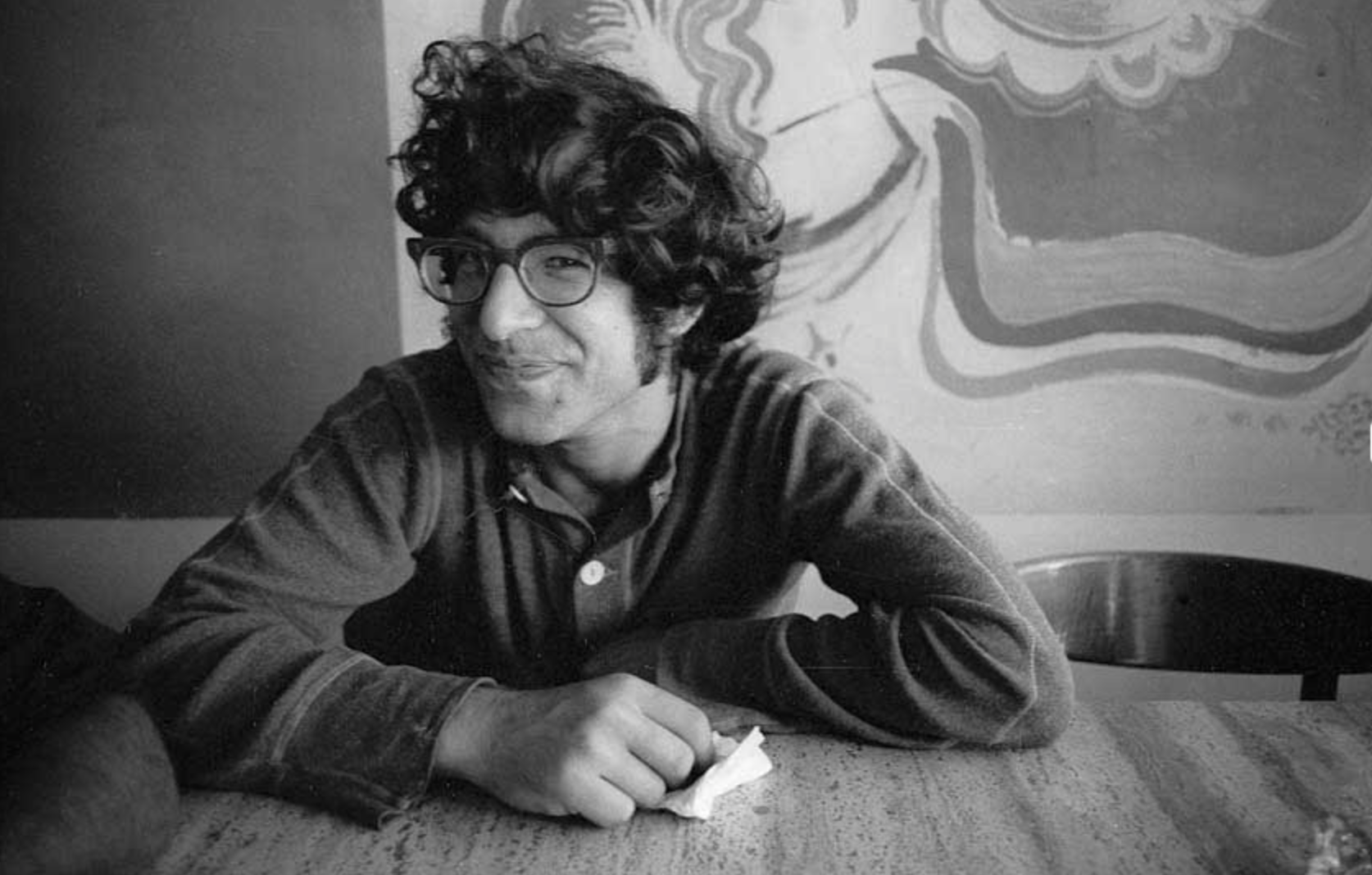

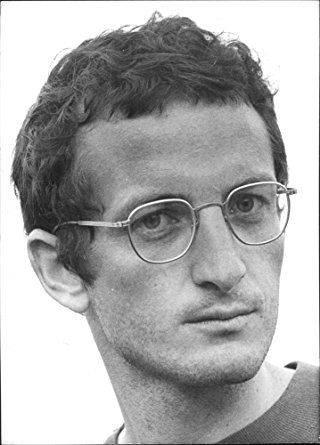

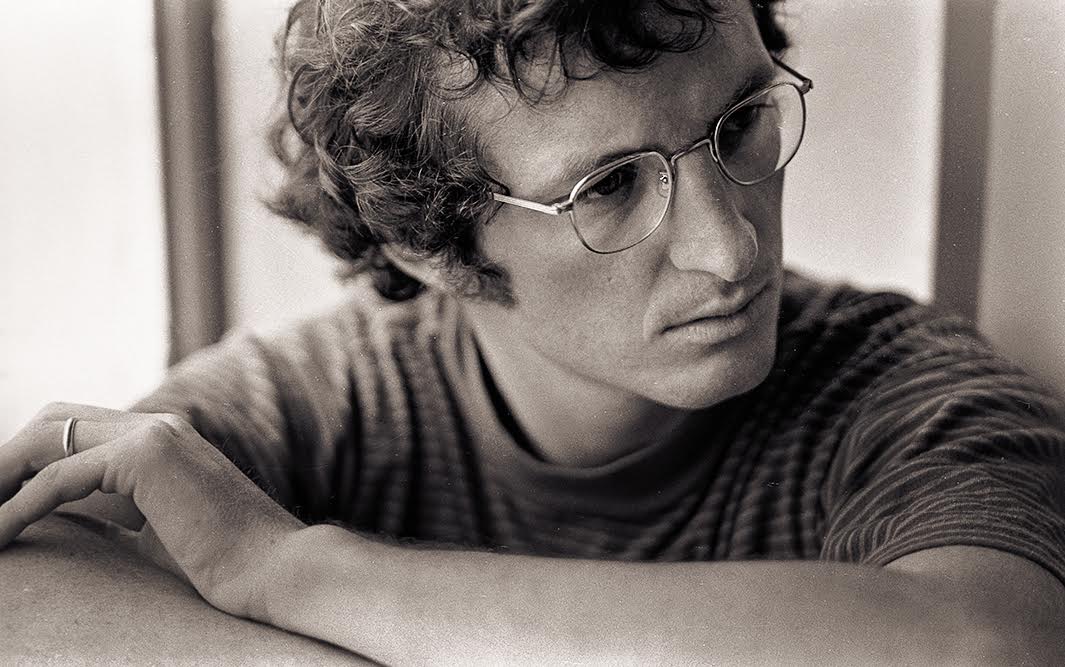

The “lone demonstrator” as described by the Associated Press who faced the National Guard bayonets in 1969 is Frank Bardacke.

He joined SLATE when he arrived at Cal in 1961. He picketed President Kennedy over the US Cuba policy. He missed the Free Speech Movement but was here for formation of the Vietnam Day Committee. He was a leader of Stop the Draft Week and for his efforts was indicted as one of the Oakland Seven. He was in the core group of founders of People’s Park. There wasn’t much in Berkeley in the 1960s that he wasn’t part of.

As we drift away from the core values and ethos of Berkeley, I think that a look at the men and women and events that defined Berkeley as Berkeley 50 years ago and cemented our reputation as a center of radical political activity is appropriate. We were forces of chaos and anarchy, and everything that they said we were, we were.

As Bardacke says, “It’s hard in this cynical age to appreciate the optimism and excitement we felt.” It’s nice to remember the fire that made us mellow. Just as my generation read of the General Strike of 1934 and the great strides forward made by progressive in the 1930s, it wouldn’t hurt for the young of today’s Berkeley to learn a little about what it was that we did, why we did it, and how it shaped Berkeley.

Frank Badacke is a prism through which we can learn and see.

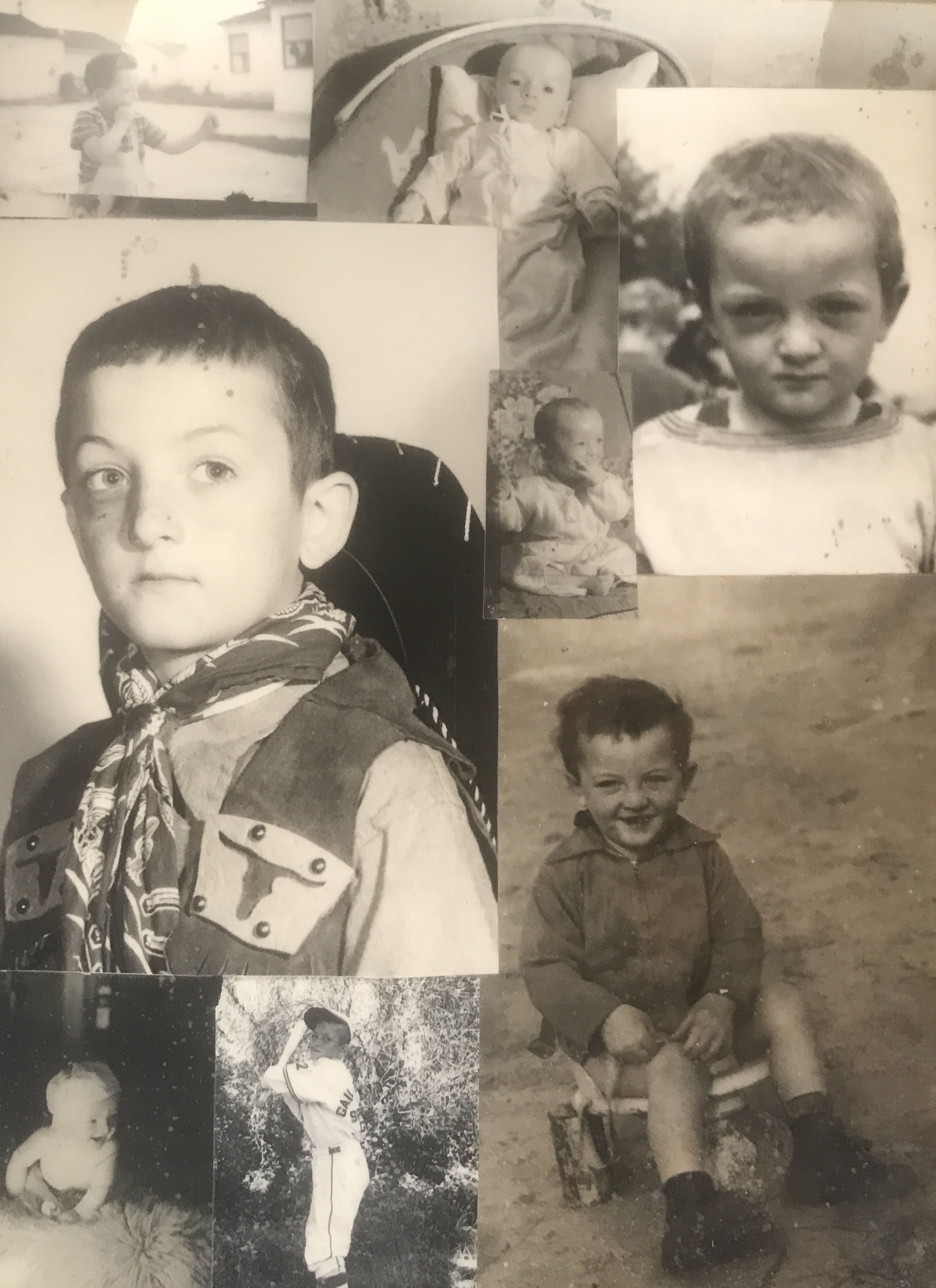

Bardacke was born in Camden, New Jersey, in 1941. That makes him not a baby boomer.

His father was from a family of Turkish Jews who settled in Odessa and then during one pogrom or another, probably 1905, made their way to Vladivostok, Russia, and from there on the international train to Harbin, the capital and largest city of Heilongjiang province in the northeastern region of China. The Bardackes were secular Jews, followers of Leo Tolstoy’s philosophy of non-resistance to evil by force, pacifism, and nonviolence. When Frank’s father, Ted, went to Syracue University, he was moving up in the world.

Bardacke’s mother was from elite colonial stock. She was destined to go to Radcliffe. She didn’t. She was moving down in the world when she went to Syracuse.

They met and married. They were Bohemian, culturally oppositional more than politically so. Mad magazine was a fixture in the house.

Ted Bardacke moved from job to job. By the time Frank was 11, they had lived in 13 different places, from coast to coast. Holding onto a job did not come easily to his father.

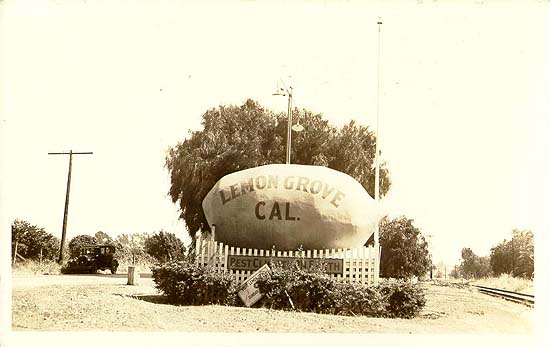

They then settled in Lemon Grove, California.

Lemon Grove is nine miles east and slightly north of downtown San Diego. The big lemon was designed by Alberto Treganza as a parade float for the 1928 Fiesta de San Diego parade, carrying the town’s first Miss Lemon Grove, Amorita Treganza. In 1930, the float was plastered to create a permanent sculpture.

La Mesa is just north of Lemon Grove. Helix High School is in La Mesa.

Bardacke graduated from Helix High School in 1959. He was the quarterback and captain of the football team. He was the class valedictorian. And he was off to Harvard, a decision which was in keeping with the ethos of his maternal lineage and a source of great pride for his father.

But it didn’t work out the way it was supposed to. He didn’t fit in. He had trouble making friends. He wasn’t interested in the Prep school graduates, and not sophisticated enough for the big city Jewish intellectuals.

He was assigned to room in Pennypacker, a dormitory built that year as apartments. It is in Crimson Yard, one of the four residential neighborhoods called Yards, at the geographic and historic center of College life.

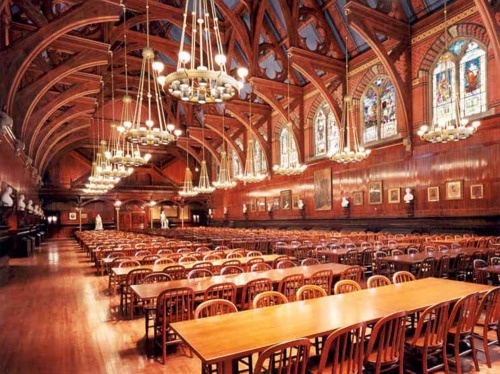

Freshmen ate in the Freshman Dining Hall. The dress code was jacket and tie.

Bardacke found his voice in opposition, not compliance. To “comply” with the dress code, he bought a ratty jacket from Goodwill which he paired with a clip-on bow tie. He left jacket and tie on a hook at the dining hall.

Kate Coleman, a good friend of Bardacke’s in the 1960s, adds that Bardacke wrote the clip-on bow tie and Goodwill jacket and nothing else. He complied but subverted at the same time.

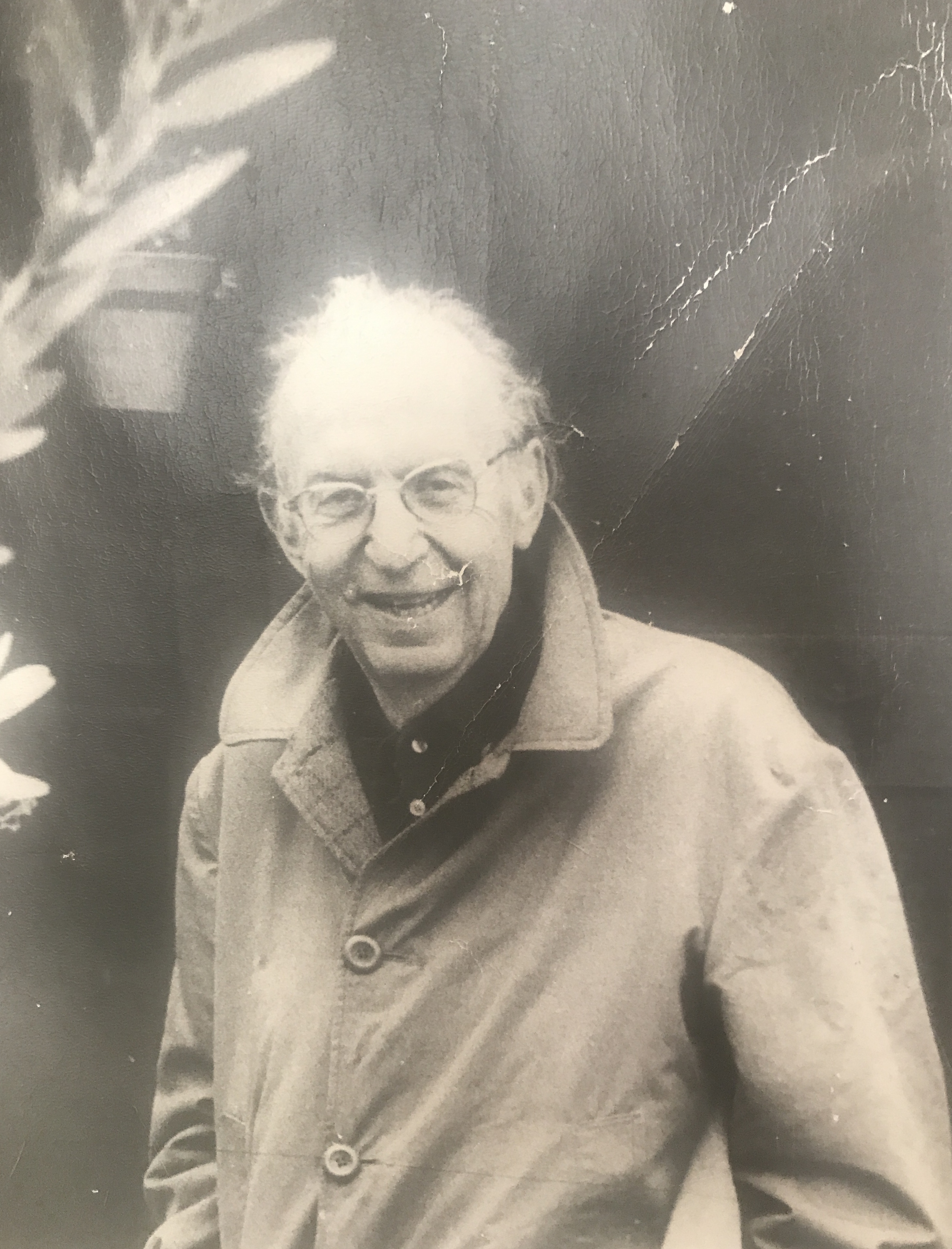

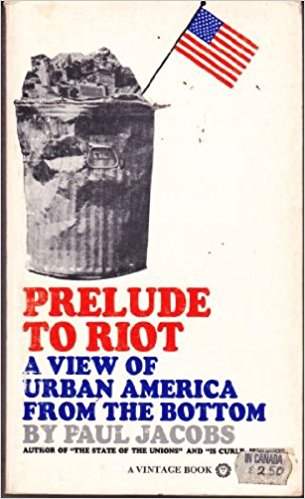

The writer and activist Paul Jacobs was Bardacke’s godfather.

Jacobs visited Harvard and opened a charge account for Bardacke at a haberdasher. Bardacke went and got measured for a wardrobe. He was humiliated. He walked out and never went back. He could not accept any vestige of elitism. When he hitchhiked, he told drivers that he went to Boston University. Even saying that he went to Harvard was too much.

In the spring of 1960, Bardacke came to know Michael Walzer, who was a teaching assistant in one of his classes.

He was and is a political theorist. He become a prominent public intellectual, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and co-editor of Dissent.

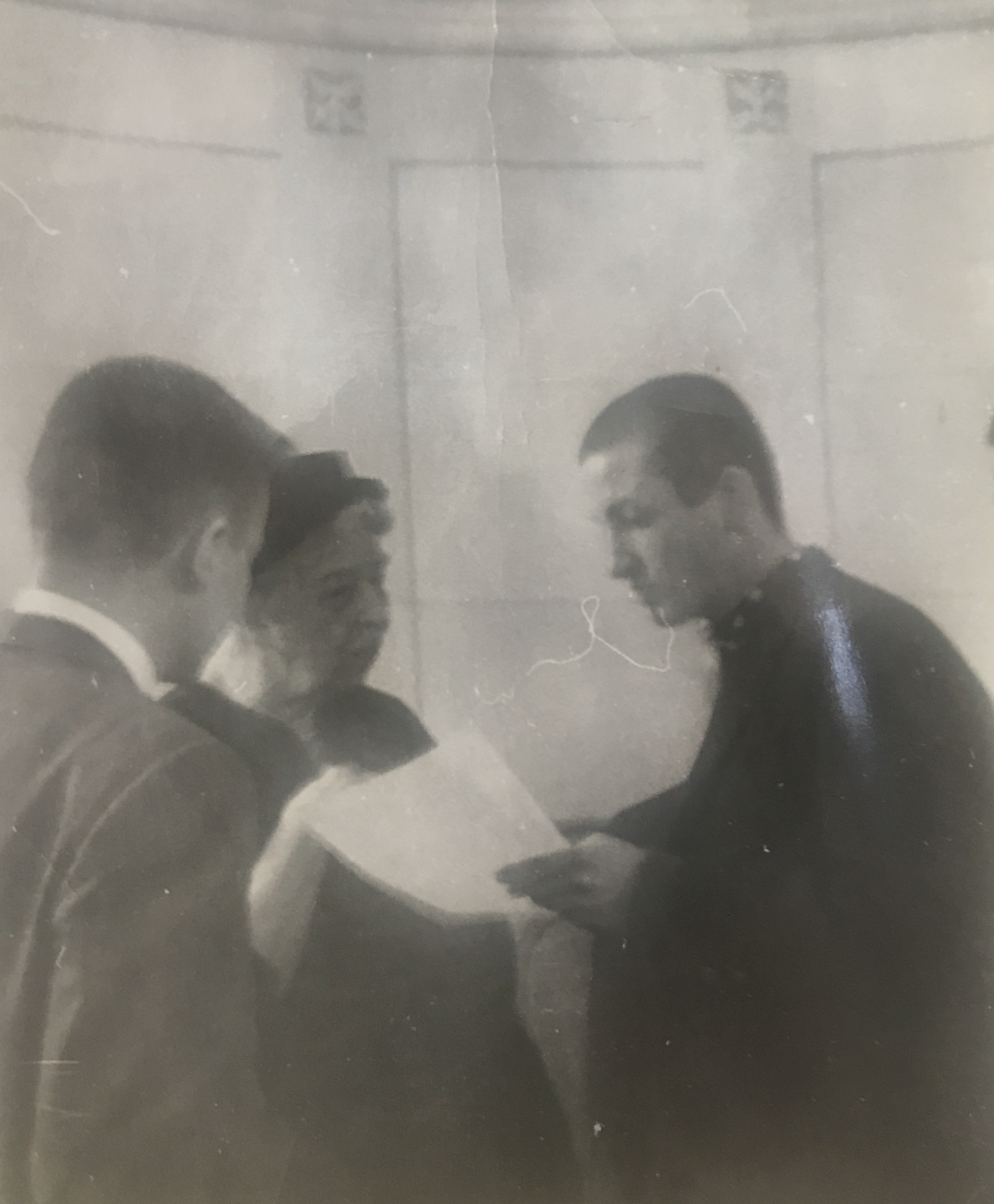

They picketed Woolworth lunch counters in Boston in support of the students protesting lunch counter segregation in North Carolina. The battle cry was “We walk so that they may sit.”

Here, Bardacke (on the right) explains to Elearnor Roosevelt what they are demanding. She called the picket lines “simply wonderful.”

In the early spring of 1960, Walzer went to the South to write a story about the sit-in movement.

On February 1, 1960, at 4:30pm, four African-American students sat down at the lunch counter inside the Woolworth store at 132 South Elm Street in Greensboro to test segregation policies at southern restaurants. Their names were Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., and David Richmond. All were students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. They were refused service. They came back the next day with many more. The movement spread throughout the south.

In the late Spring,Bardacke and another activist on the picket line, David Koulack, drove to Greensboro, North Carolina. Bardacke and Koulack picketed the Greensboro Woolworth’s. They had raised funds at Harvard under the name of the Emergency Public Integration Committee and they distributed the money.

They got back to Harvard in time for finals.

P.S. On Monday, July 25, 1960, the lunch-counter campaign prevailed and lunch counters began to be desegregated.

There was one more chapter in Bardacke’s political education at Harvard.

He went to see “Operation Abolition” at Harvard’s ROTC program. The movie was a clumsy rightwing attack on the Berkeley students who had protested HUAC’s appearance in San Francisco City Hall in 1960 and had been arrested and fire hosed down City Hall’s steps.

The movie had the opposite effect of what had been intended. Bardacke and many others were inspired by the movie and drawn to Berkeley.

In the spring of 1961, Bardacke was on disciplinary probation at Harvard. He flunked Russian. Bardacke met with the school administration who told him that his connections with Harvard were severed for the next 18 months. It was suggested that he join the Army and become a man.

Which is how Frank Bardacke came to Berkeley in the fall of 1961. He stayed here until the fall of 1970, with a year off in Uganda for good behavior in 1964.

I asked him what his first impression was of Berkeley. He said, “Heaven.”

Bardacke cites Mario Savio’s explanation of why San Francisco and Berkeley were such incubators for new ideas. Cal was a state school with high standards, attracting an intelligent student body. San Francisco had been a home to Beat counterculture. And, the Left was strong; being a member of the Communist Party USA could help you get a job, not get you fired.

He also speaks of “bureaucratic anarchy” at Cal. Harvard was a relatively small university with constant mentoring of students by proctors and professors. Cal was huge. Nobody was tracking what you did. You were on your own. Anarchy!

Ideas were everywhere.

In 1962 Robert Scheer, David Horowitz, Maurice Zeitlin, Phil Roos, and Sol Stern founded Root and Branch: A Radical Quarterly. It lasted two issues. That’s not the point. At the same time, that is the point.

Still in the ideas department, Bardacke and Marvin Garson put out two issues of The Wooden Shoe. The wooden shoe was used as an icon by 19th and early 20th century anarchy-syndicalists. The French word for “shoe” is sabot. The Oxford English Dictionary gives the following eytmology for the English word sabotrage: “French, < saboter to make a noise with sabots, to perform or execute badly, e.g. to ‘murder’ (a piece of music), to destroy wilfully (tools, machinery, etc.), < sabot. So Dutch anarchsits factory workers threw their Dutch wooden shoes into factory machinery to shut it down, and because of the wooden shoes we have the word “sabotage.” Cool!

Garson wrote that The Wooden Shoe was “Priced at a nickel. Its motto was: What this country needs is a good nickel fortnightly. The price went up to a dime on the second issue. There were only two issues.”

I think now is the time for a brief digression about Garson.

Garson started his college career at Brandeis. He was ordered to withdraw for “conduct unbecoming a Brandeis student” – using a phony telephone credit card. Which we all did at one point or another.

He went to work in the City Room of the New York World Telegram and Sun. He scrimped and saved, and he and his wife went to Cuba in 1960. Back in New York, he went to meetings of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, which was, he wrote, “crawling with Trots.”

He was recruited by James Robertson, a Trotskyist involved with the Young Socialist League. He was admitted to Cal, came, matriculated, and eventually earned a BA in European history in 1963. Garson remained a good friend and theoretical inspiration for Bardacke over the years.

Back at Cal, there were the ideas and then there was action.

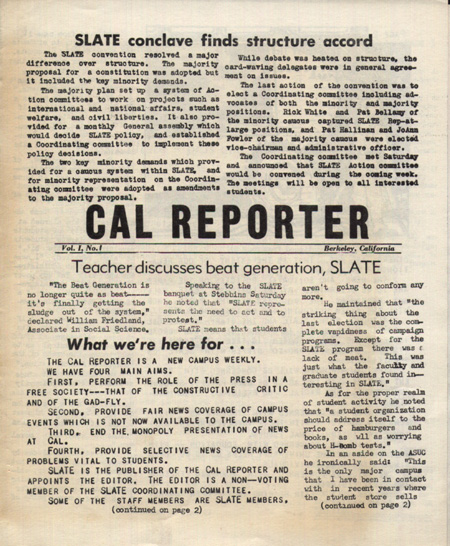

And SLATE was everywhere.

SLATE was formed in 1957. It was not an acronym, just the idea of a slate of like-minded candidates running for student government. Their platform – racial equality, free speech, banning the bomb, voluntary ROTC participation among others – included a number of off-campus issues. Just running on issues instead of personal popularity was a big step.

Bardacke met and was informed by working with several of the SLATE founders. Mike Miller was a product and believer in the Saul Alinsky model of community organizing.

Photo: http://www.nlgsf.org/news/join-us-2017-testimonial-dinner-april-29-2017-yerba-buena-center-arts-san-francisco

He also met Peter Franck, a SLATE founder.

Photo: http://www.westword.com/news/david-horowitz-has-turned-taunting-muslims-into-a-spectator-sport-5118887

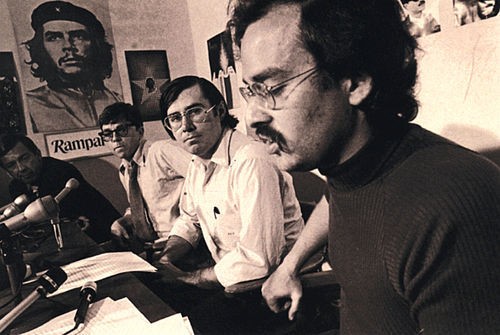

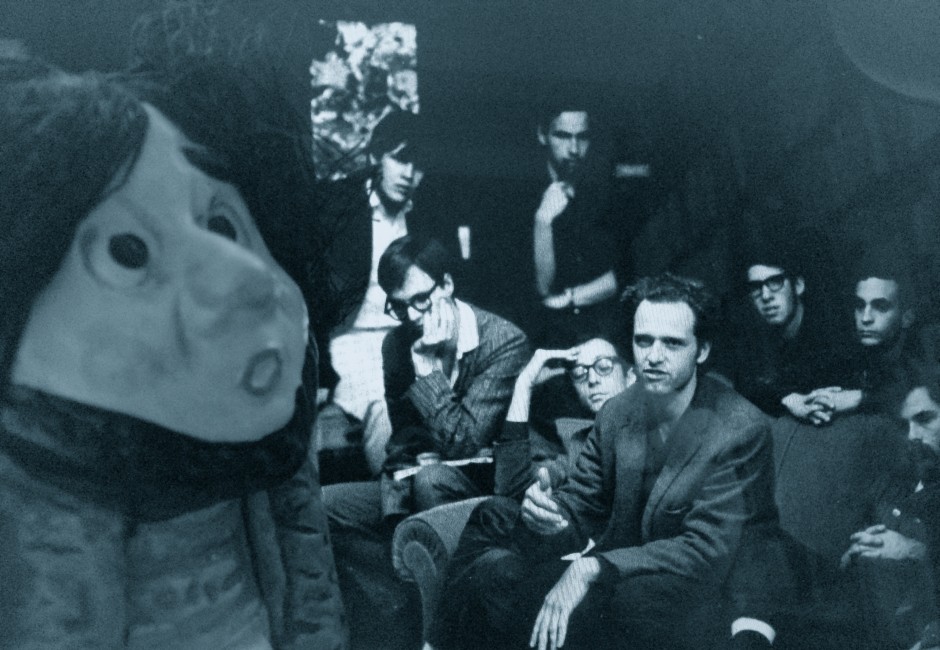

And he met and worked with David Horowitz (on the far right in the photo above), who would become co-editor of the left magazine Ramparts before changing teams and playing for the neo-cons.

Bardacke’s friend Garson dabbled in traditional sectarian politics, joining the International Socialists (IS), a Third Camp Trotskyist group. When Lenny Glaser (now living under the name Lenni Brenner) was kicked out of the IS because of his advocacy of marijuana legalization, Garson and his wife Barbara defended Glaser. The Garsons were then kicked out. Garson wrote that “two grim-faced Bolsheviks representing the executive committee” told him that he would be resigning.

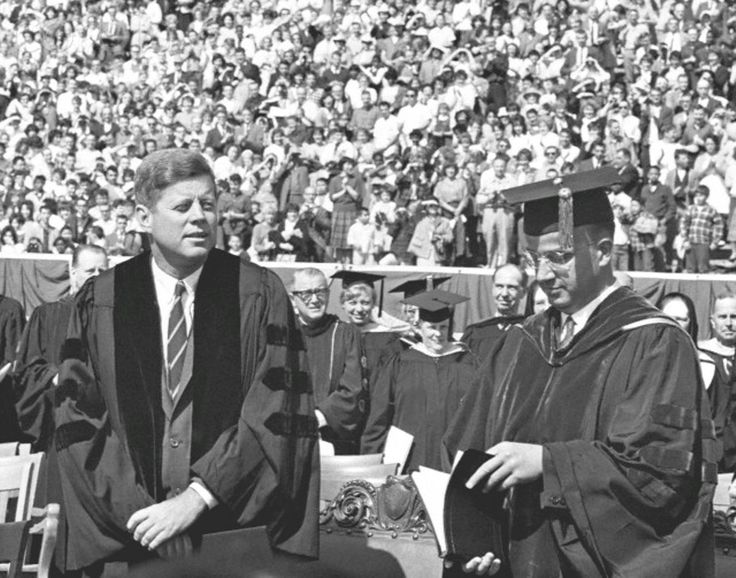

On March 23, 1962, President Kennedy spoke at Cal.

Marvin Garson wrote this: “Me and my good buddy F.J. Bardacke were determined to wipe the smirks off all those bastards’ faces. Why not picket him when he comes.”

Marvin Garson estimated that he and Bardacke and about 450 people picketed Kennedy, and that 75,000 people crossed the picket line.

SLATE tried to control the wording on picket signs, keep it civil and adult and respectful. There were outliers.

In October, 1963, Madame Nhu spoke at Cal. As the wife of Ngô Đình Nhu, who was the brother and chief-advisor to President Ngô Đình Diệm, she was the de facto First Lady of South Vietnam from 1955 to 1963. The San Jose State University newspaper referred to her as “South Vietnam’s best little warrior, the radiant Mme. Ngo Dinh Nhu.”

Bardacke joined SLATE members picketing the event. Respectfully.

Bardacke remembers: “There was opposition to her speech. If I remember correctly, the compromise was that she could speak, but that after the speech (or before the speech, or in some way in conjunction with the speech) Robert Scalapino was going to debate Bob Scheer on the war. But she went ahead and spoke in Harmon Gymnasium. It was a full house. And she was applauded politely. There was a small demonstration outside. This was the time that Lenny Glaser was giving his talks at Bancroft and Telegraph. As the students left Madam Nhu’s speech, Lenny, the practiced outdoor orator, was standing on the ledge above the steps delivering his own speech, admonishing the students for applauding. Here’s the part I remember. ‘You failed today. You failed a test in politics. And when you fail in politics it isn’t like failing in school. It matters. And you will pay. You will pay in the jungles of Vietnam, in the pampas of Argentina, in the mountains of Nicaragua. When you fail in politics, you pay in blood.’ It was magnificent. He held the attention of so many students, that the street across from Harmon was blocked. After a while the cops came. Made their way slowly through the crowd in a cop car with the siren blaring. The arrested Lenny. Put him in the car. Immediately some one sat down in front of the car, and was followed by many others. Lenny was in the back seat, delighted. ‘Oh you are in trouble now,’ he told the cops. For a while it was stand off. Finally, the confused cops let Lenny go, and were permitted to drive off. It was dress rehearsal for Jack Weinberg. and the FSM.”

The headline in the Examiner was “Students Mob Cops at UC.” The headline in the Daily Cal was “Near Riot as Mme. Nhu Exits”

In early 1964, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) picketed San Francisco auto dealers over their discriminatory hiring practices.

Bardacke joined SLATE members in picketing. Respectfully.

And then came the Free Speech Movement in the fall of 1964.

Bardacke missed it.

Bardacke went to Kampala, Uganda for the year, as a research assistant.

His good friend Marvin Garson almost missed the FSM but didn’t. In 1963 Garson and wife went to Europe for a year. They returned to the United States in July, 1964. Things were humming. There were the Harlem riots (July 16 and 22, 1964) which began after 15-year-old James Powell was shot and killed by police Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan, the Mississippi summer for SNCC, the Freedom Summer murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality’s plan for a 500-car stall-in to shut down the New York World’s Fair. and the ascendancy of Goldwater. Yes indeed things were humming.

Garson was here for the early weeks of the Free Speech Movement but in December he went to Dallas where he worked with Mark Lane investigating the assassination of President Kennedy.

This is a screen grab from a January 29, 1964 news conference with Mark Lane and Marguerite Oswald.

When they got their BA’s, Garson and Bardacke swore to each other that they would not apply to graduate school. They embraced Flaubert’s axiom “hatred of the bourgeois is the beginning of wisdom.” Graduate school was for the bourgeois. It was bougie.

As letters from Berkeley came to the Bardacke describing the unfolding of the Free Speech Movement, he concluded that he had blown it by leaving Berkeley. Kampala was far away and Bardacke couldn’t get back.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to the other, they each applied to graduate school at Cal. They matriculated in the fall of 1965 for graduate school in political science.

How was Berkeley? Bardacke says it was “raging.” Good description!

The Vietnam Day Committee was the main event in town.

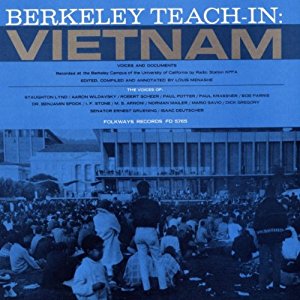

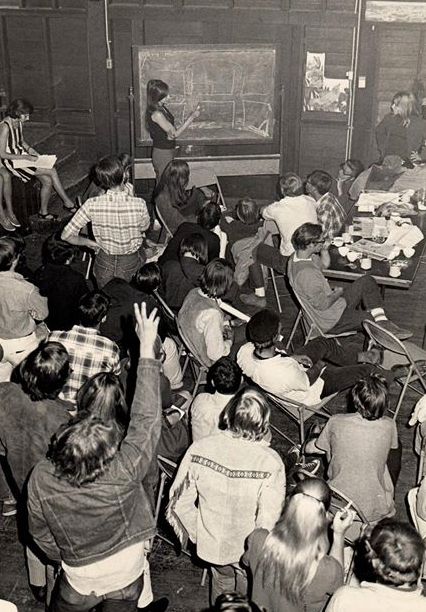

The VDC emerged from a 35-hour-long teach-in about Vietnam at Cal. on May 21 and 22, 1965.

Speakers included I.F. “Izzy” Stone, Robert Scheer, Willie Brown, Berald Serreman (acting chairman of the Anthropology Department)and Eugene Burdick from the political science department debating department chair Robert Scalapino. Leaders of the VDC included the very Old Left Paul Mantauk and the very New Left Jerry Rubin, Stew Albert, and Abbie Hoffman.

Rubin is speaking from the ground, hands spread. Bardacke found Rubin very earnest, and someone who was all-in for whatever he did he was all-in. His first impression of Rubin was at a terrace on campus where armchair revolutionaries gathered to talk. As they talked, Rubin took notes. He wanted to learn. Bardacke soon came to appreciate Rubin’s skill with hyperbolic language and attracting attention from the press. He was friends with Rubin.

Garson admired Rubin. Rubin had announced the Bob Dylan, Norman Mailer, and Jean Paul Sartre were coming to the teach-in. They weren’t and didn’t. At the Teach-In, Rubin announced that there would be International Days of Protest on October 15 and 16. No such event was planned. Garson admired this though – “Jerry knew the trick. You don’t suggest or propose anything; all you have to do is announce it – in the right time, place, and manner of course.”

The goals of the Vietnam Day Committee were:

- National and international solidarity and coordination on action.

- Militant action, including civil disobedience.

- Extensive work in the community to develop off-campus grassroots opposition and to benefit from the militancy of direct action.

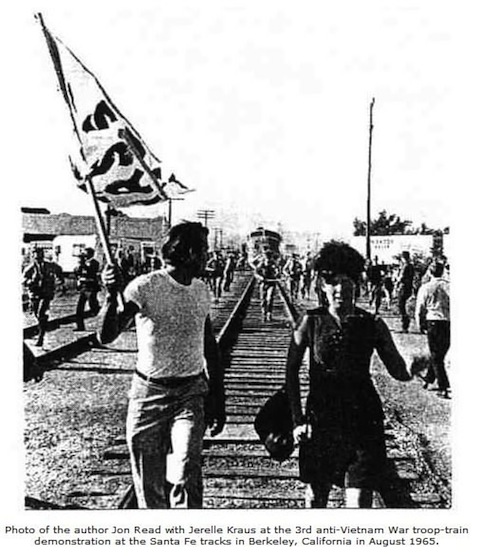

In August 1965, the VDC led protests on the Santa Fe railroad tracks, trying to stop trains carrying newly inducted troops from Oakland. There were dramatic moments but no injuries. Bardacke did not take part in the train protests.

On the left, Jack Weinberg of Free Speech Movement fame; in coat and tie, Michael Lerner; with glasses and a cigarette Marvin Garson. Photo by Michael James at michelgaylordjames.com

Momentum grew with each march and demonstration.. Strategic decisions were made in late-night meetings and on-the-fly discussions.

In January of 1966, Leo Bach took over the Berkeley Free Press. Leo was a solid old lefty who had a small Christmas card imprinting business in his garage. The Berkeley Free Press was not operating at the moment, and in the absence of the usual left-wing printer, Leo had taken on a monster order for a leaflet written by Marvin Garson. Bardacke printed thousands of copies.

On one side, the leaflet had a picture of two Vietnamese babies who had been burned by napalm. On the other, the text began: “If you met the father of these children, what would you say to him?” John Seltz intended to bomb the leaflet over the Rose Bowl game on January 1, 1966, and everything was in the plane and ready to go, when on the runway in Pasadena, the airplane had a flat tire. They couldn’t get it fixed in time.

But nothing happened. No 250,000 leaflets falling like a malevolent snowstorm; no national TV coverage. No nothin’. UCLA beat Michigan 14-12. What an anticlimax.

Seltz, not one to give in, got another plane, painted out its identification numbers, and bombed the whole Bay Area, instead. Not nearly the impact, of course, but better than nothing.

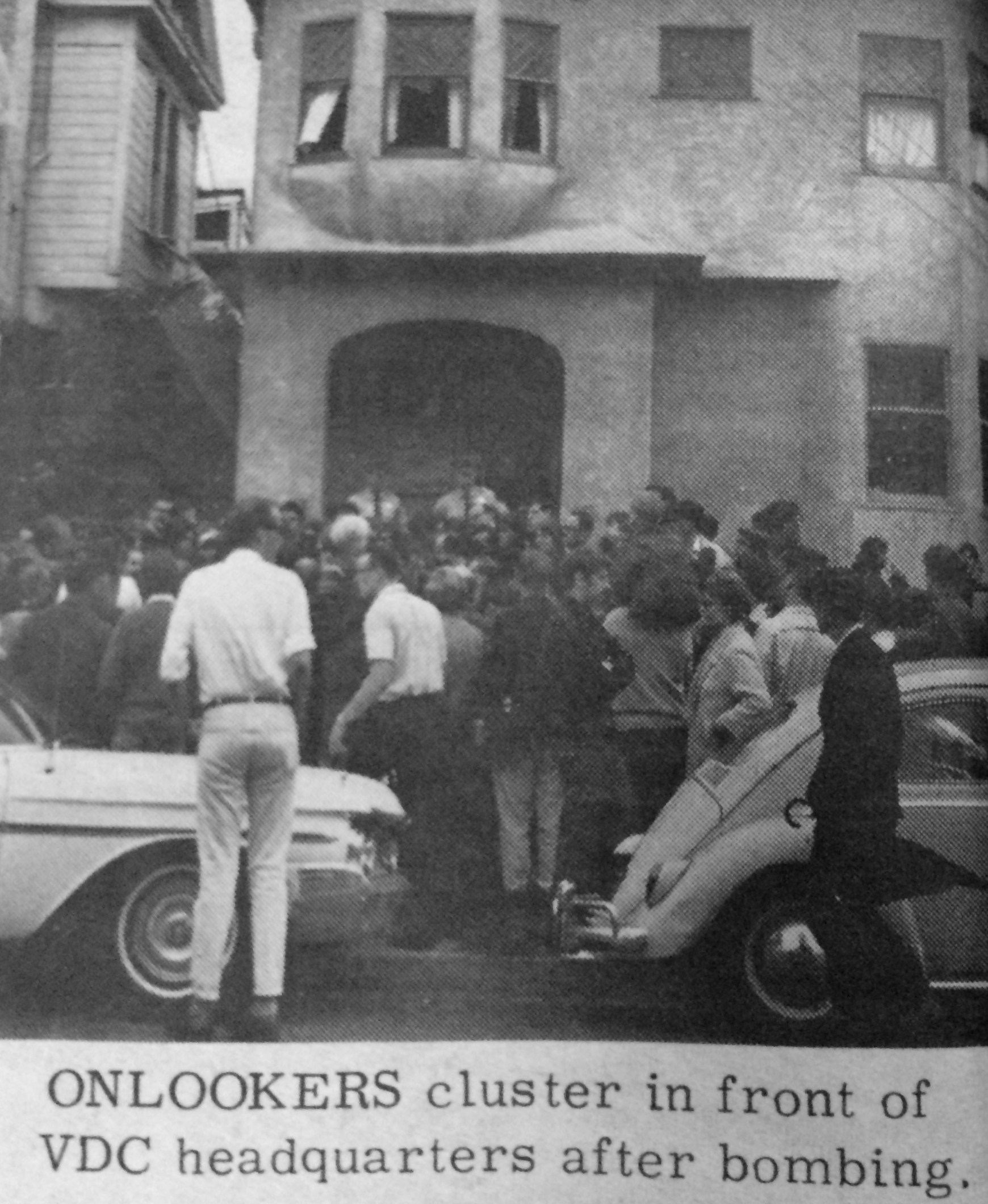

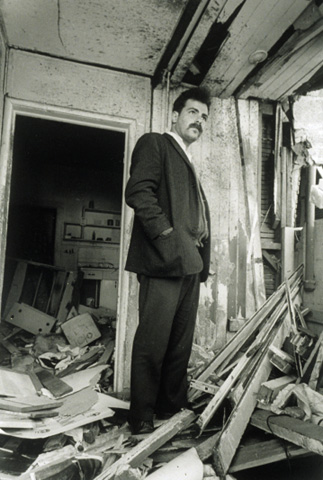

In April 1966, a bomb exploded at VDC headquarters on Fulton Street.

Here Jerry Rubin inspects the damage. Of the bombing, Jack Weinberg wrote:

At one-thirty in the morning of April 9, 1966, we were startled by the sound of an explosion. It sounded distant, but big. In seconds, the phone rang and it was Pam Mellin asking if we had heard that the VDC headquarters had been bombed. Jesus H. Christ. We jumped into Leo’s car and went over to 2407 Fulton where the headquarters were, and the street was full of fire engines and ambulances and cops. Red lights flashing all over the place and the whole front of the building just plain gone.

All the VDC leaders had been there having a meeting in the living room. They had just adjourned, and gotten up and walked together into the kitchen to get some eats, and the room followed them out. One minute earlier and everyone would have been jam. That would have changed things a lot. Danny Kowalski was still in the attic. The cops found him, sound asleep. At first they thought he was dead. He’d slept through the whole thing and could hardly believe it.

The VDC bombing occurred one day after the Oakland Tribune printed an article about a VDC fundraiser in UC’s Harmon Gymnasium, which was represented as a drugged-out wild sex orgy. The Jefferson Airplane had played, and many people were stoned on acid (which was still legal), but the only concrete evidence of an actual orgy was one used condom on the floor of the balcony.

The April 15th Barb had two stories on the bombing. One proclaimed “Light Bomb Injuries Inflicted.” The second quote Bob Scheer as saying “People who have been slandering the VDC and others who are opposed to this war will have to bear the responsibility for this bombing.”

On December 7, 1966, Bardacke took part in the Maskorcion and Yellow Submarine demonstration.

Photo by Howard Harawitz

This photograph purports to be of Bardacke speaking at the “Maskoricon and Yellow Submarine Demonstration.” Bardacke isn’t sure: “I don’t remember much, except that it was awfully silly. The masks were making fun of the administration’s characterization of us; we started singing “Yellow Submarine” when the serious socialists started singing “Solidarity Forever.” I think it was during one of the student strikes.”

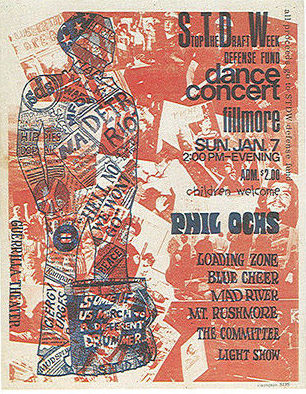

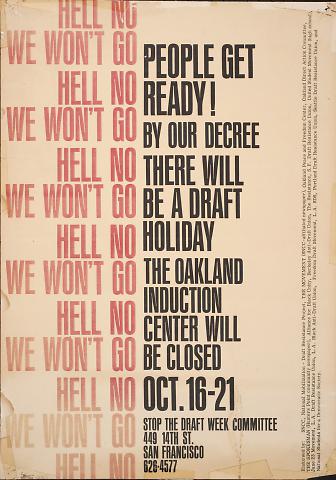

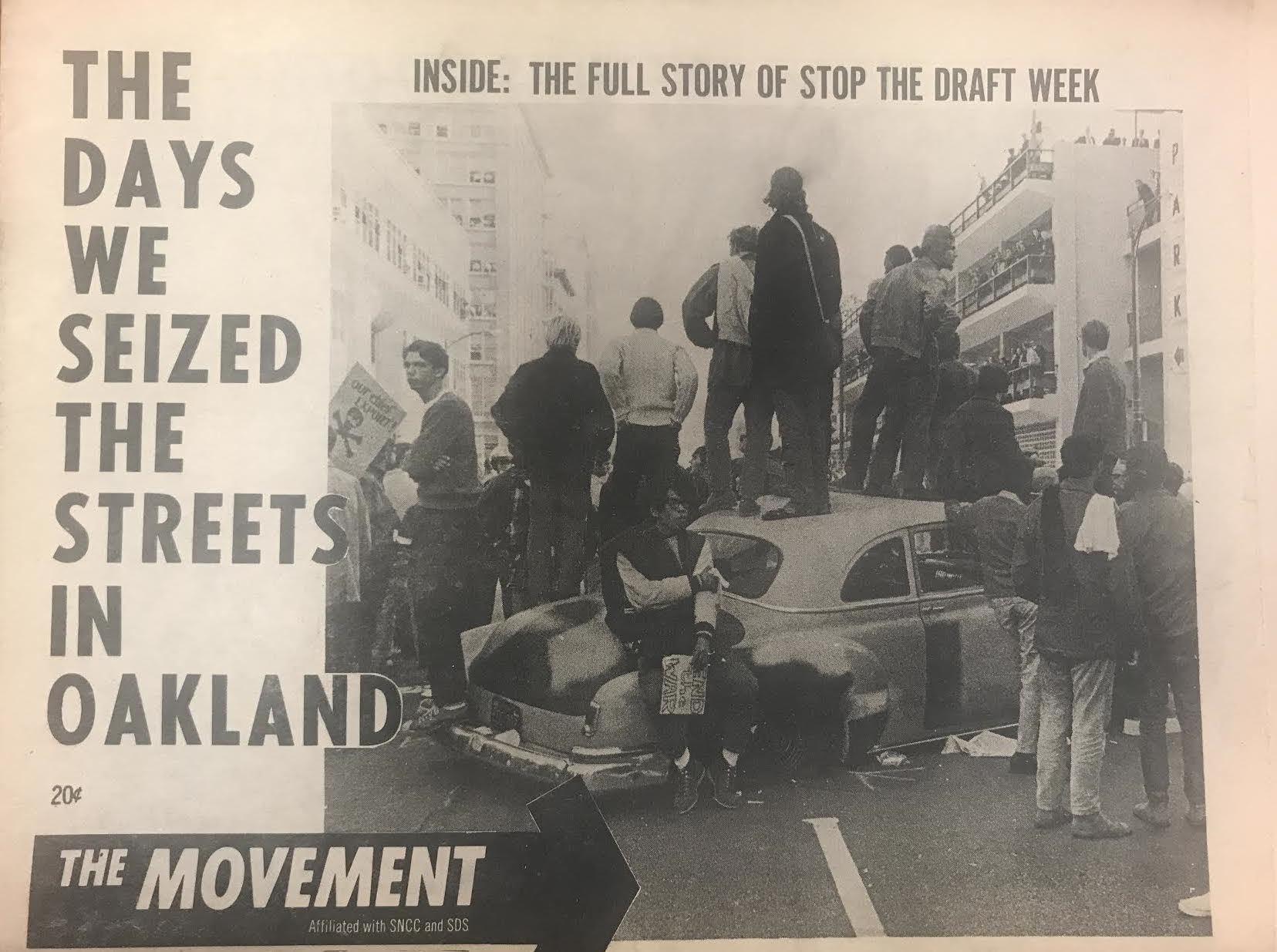

The event that elevated Frank Bardacke’s profile was Stop the Draft Week in 1967.

A lot of planning went into Stop the Draft Week.

Bardacke says that the plans for the week reflected a change from protest to resistance. “We weren’t protesting, we were stopping the war.” In retrospect, Bardacke sees how important it was to focus on the draft, which affected the sons of privilege as well as the poor and powerless.

At the time, Bardacke felt that young white radicals were wandering in the wilderness in the summer of 1967. Anti-war activity seemed without purpose – the demonstrations hadn’t ended the war. The hippie movement informed the culture of the left, but it was not a meaningful alternative for most.

The rhetoric of the VDC did not want for audacity – “By our decree there will be a draft holiday…” Those are audacious words. Looking back, David Lance Goines said to Bardacke, “No wonder they didn’t pay attention to us – we were kids.” Kids who decreed!

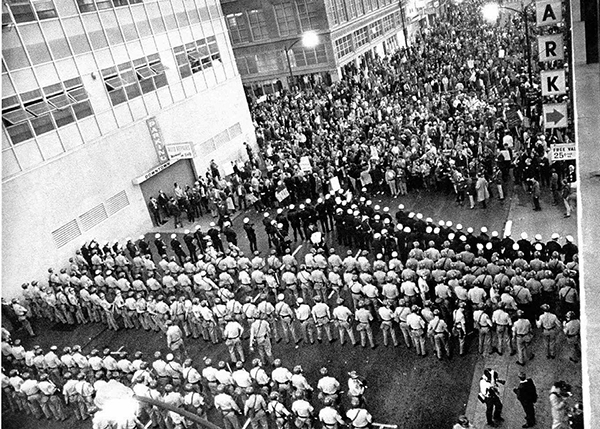

The VDC leaders did not plan to get arrested in Oakland. They had no interest in the concept of “moral witness.” They were inspired by the militancy of the Black Panthers and the uprisings/riots in Watts (1965), Detroit (1967), and Newark (1967). They were determined not to get arrested, and they trained in rescue tactics. They did not want to provoke discussion about Vietnam among the white middle class. They wanted to prove to “black and young workers” that they were serious and strong. The Tribune headline validated the feeling – “Guerrilla War in Oakland as Protestors Try Street Blockade.”

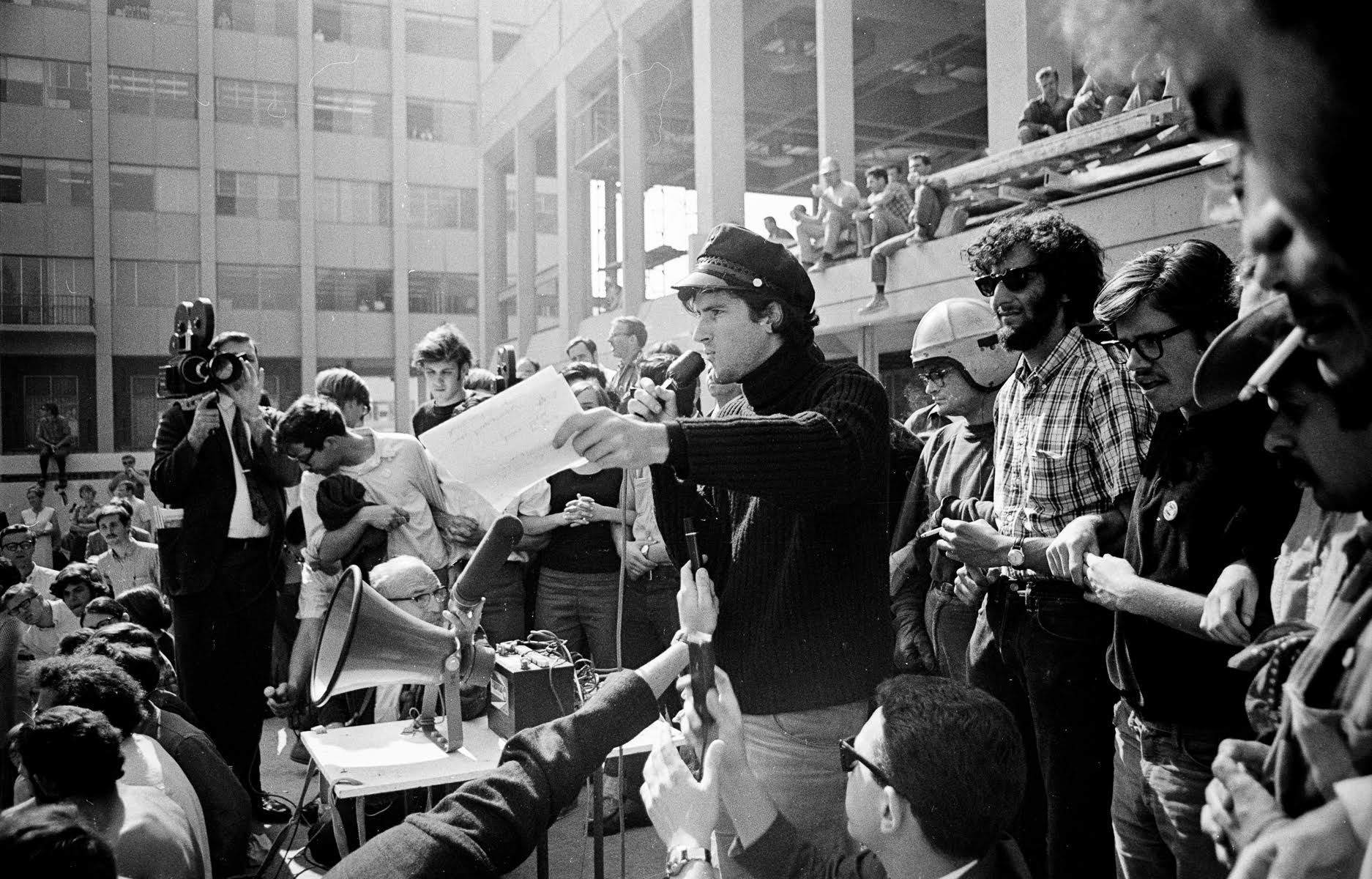

The Steering Committee for Stop the Draft Week was diverse. Bardacke points to the leadership of Terry Cannon, shown above at a Stop the Draft rally on Sproul Plaza in October 1967.

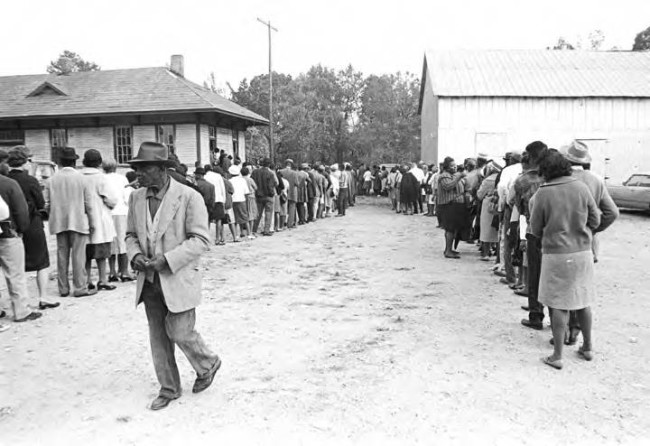

Election day 1965, Lowndes County. Photo: https://zinnedproject.org/materials/lowndes-county-and-the-voting-rights-act/

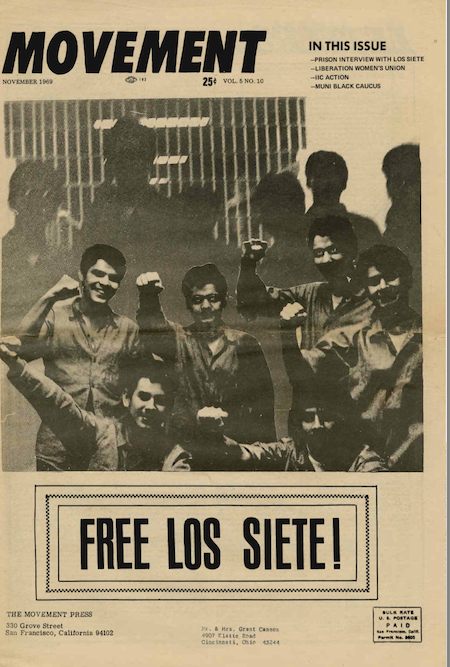

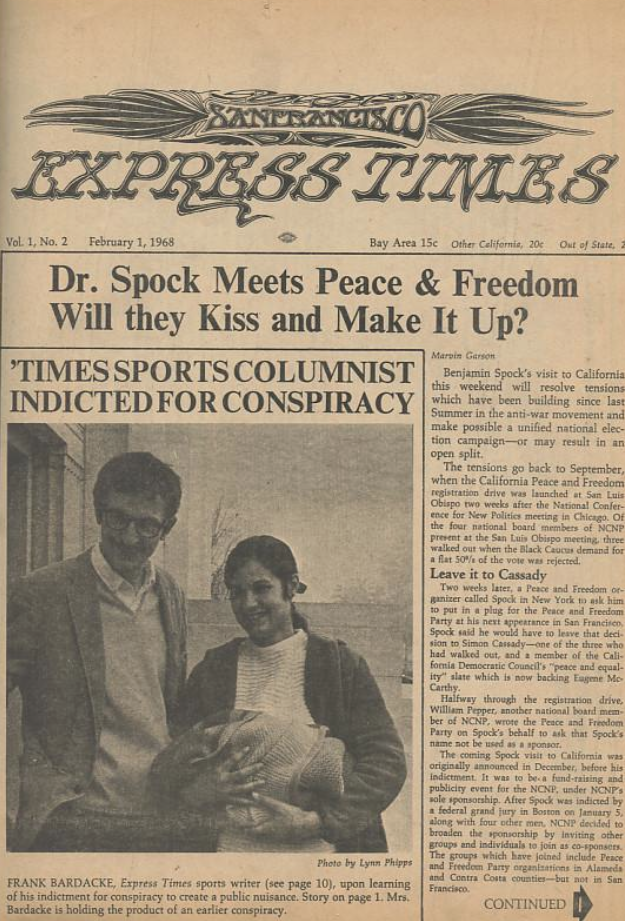

Cannon had served as a field secretary for SNCC in Lowndes County. In 1964, Cannon was asked by Mike Miller to set up a newsletter that would keep West Coast SNCC supporters in touch with what was happening in the South.

Cannon edited the newsletter (soon a newspaper), named The Movement. It was democratic and collective. Its signature approach was using organizers as the sources for most of their stories. Its staff were organizers. They went to the field and talked with organizers and they wrote about organizing. Cannon left The Movement to organize Stop the Draft Week.

On the first day of the demonstrations at the Induction Center on Clay Street in Oakland, several dozen protestors sat in front of the door – moral witness.

One of the protestors was Joan Baez. After those sitting were arrested, a massive police escort led the buses of draftees to the center and protected them as they went inside to be inducted into the Army.

Some of the draftees showed solidarity with the protestors.

The crowds grew each day of the week. The steering committee improvised throughout the week, learning each day what worked and what didn’t work, coming to understand what the police would do and when. Reese Erlich described the building of momentum: “Tomorrow we go down there twice and strong as we did today. We go down there with twice as many shields as we did today. And we go down there with everybody wearing one of these (surplus military helmet).”

During the week, a group calling itself “Men of the Resistance” came to the induction center and burned their draft cards. David Harris had been a founder of the group and was in Oakland for the protests.

Burning draft cards had been going on for two years, but it remained a dramatic gesture with consequences. Through the Free University of Berkeley, anti-war activists had been counseling students at Berkeley High to not register for the draft. They decided to put their money where their mouth was and burn their own cards.

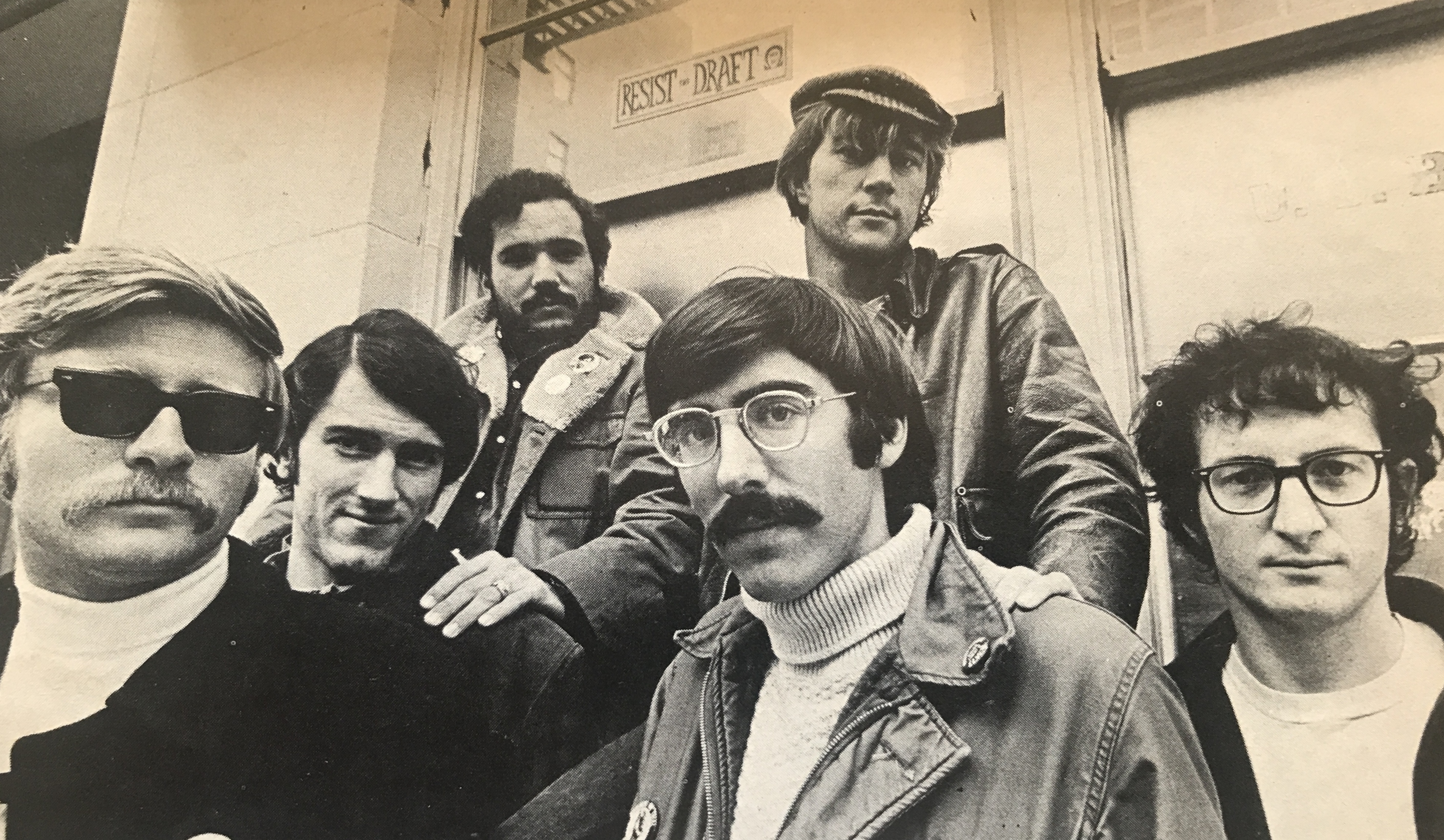

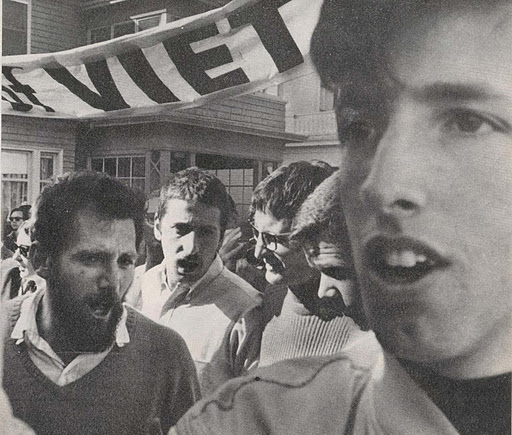

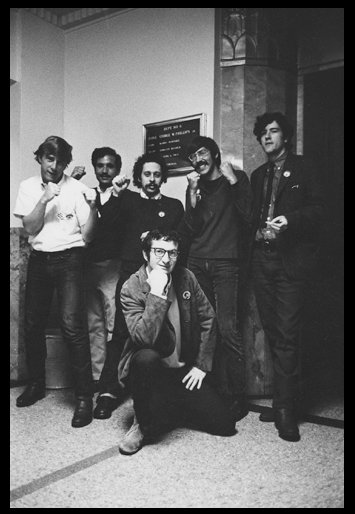

On Friday, shit got real. This photo was taken about five minutes before the police attacked. Steve Weissman is on the left with a beard, Jack Weinberg is in the center, and Frank Bardacke in the center with glasses.

When the police attacked the protestors on Friday, the protestors did what they planned – they blocked inductions and for the most part avoided arrest.

Bardacke wrote later: “We called our barricaded streets liberated territory. We did not loot or shoot. But in our own way we said to America that at that moment in history we do not recognize the legitimacy of American political authority. We controlled the downtown area of Oakland for most of the day. And the cops were outnumbered and confused and scared and we shut down the induction center.” He called himself and the others “political outlaws,” foreshadowing the lyrics of the Jefferson Airplane’s We Can BeTogether in 1969 – “We are all outlaws in the eyes of America .”

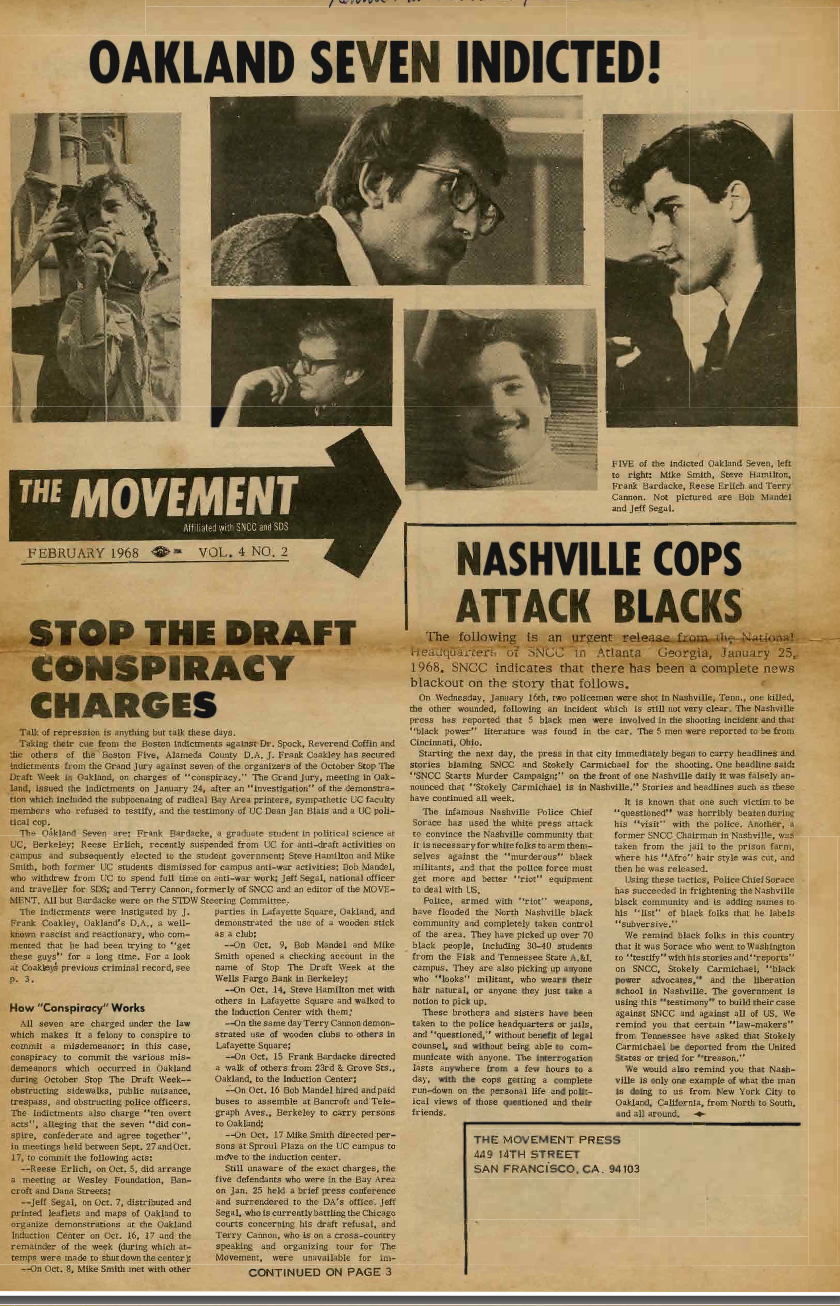

And then? In early 1968, seven demonstrators, including Bardacke, were indicted for their actions. It took Bardacke by surprise. He had heard no hints of a grand jury or a possible indictment. He faced the possibility of a three-year prison sentence.

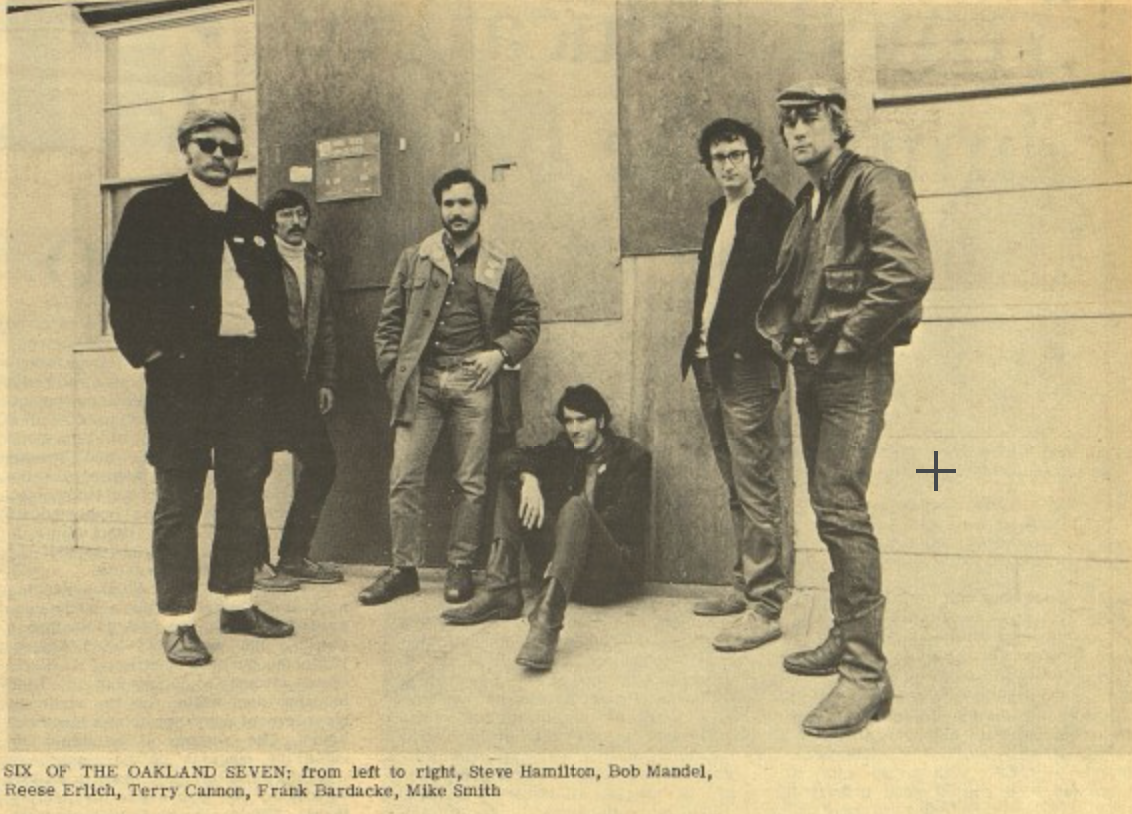

Seven participants in the Stop the Draft demonstrations were indicted. They instantly had a name – the Oakland Seven. They were indicted for conspiring to commit misdemeanors in their planning for the demonstrations in October 1967. Some of them had been on the Stop the Draft Week Steering Committee and some were Monitor Captains in the crowd. They were Mike Smith, Steve Hamilton, Frank Bardacke, Reese Erlich, Terry Cannon, Bob Mandel, and Jeff Segal. Karen Jo Koonan, one of the main leaders of the Steering Committee, was not indicted, presumably because she is a woman.

The New York Review of Books gave the following thumbnail sketch of the seven, with a point of reference the night that they were (SPOILER ALERT) acquitted:

The Oakland Seven are young, white, and full-time politicians. The night they were acquitted, two of the Seven were in jail. Jeff Segal, who used to be anti-draft co-ordinator for national SDS, was serving a four-year sentence for refusing induction into the army. Mike Smith was in jail for sixty days for committing trespass and being a public nuisance during a demonstration in 1966. In 1968 Mike Smith starred in a movie about himself called The Activist. He worked in the Free Speech Movement, and spent six months with SNCC in the South. Five of the Oakland Seven had been Berkeley students. Four, including Mike Smith, were suspended for political activities.

Terry Cannon is twenty-nine, the oldest of the Seven. For two years he was an organizer for SNCC: he has written books about mathematics and he founded the newspaper The Movement. He is about to serve three months in jail for using profane language during a demonstration. The evening of the verdict, Frank Bardacke brought a television set into the courtroom and watched the San Francisco vs. Los Angeles basketball game. Frank Bardacke occasionally teaches political science. He is a political leader in the Berkeley radical community. Steve Hamilton was active in the Free Speech Movement. He lives in Richmond, an oil-town on the North Bay, and organizes among white oil-workers. Bob Mandel worked in SNCC for two summers. He used to be a full-time anti-draft organizer in Berkeley. Before the trial, Reese Erlich worked for the Peace and Freedom Party.

This was not the first political trial of the decade, and nor was it the last. At least two had come before.

Dr. Benjamin Spock, William Sloane Coffin, Michael Ferber, Mitchell Goodman, and Marcus Raskin were indicted and tried for conspiracy to counsel, aid, and abet resistance to the draft. The trial was conventional. Four were convicted, but none did time

The Catonsville 9, including the Berrigan Brothers, were tried in 1968. They burned 378 draft files with home-made napalm in Catonsville, Maryland. It was a more or less conventional trial, although the defendants often referred to a higher law that they were following—God’s moral law—as well as such precedents as the Nuremberg war crimes trials after World War II.

In their defense, they deployed legal and political strategies.

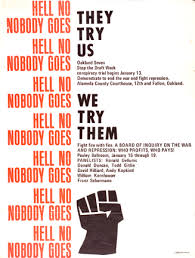

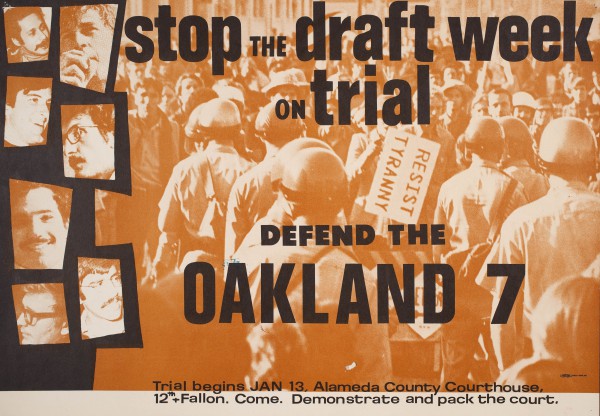

A support committee was formed and took on a life of it own.

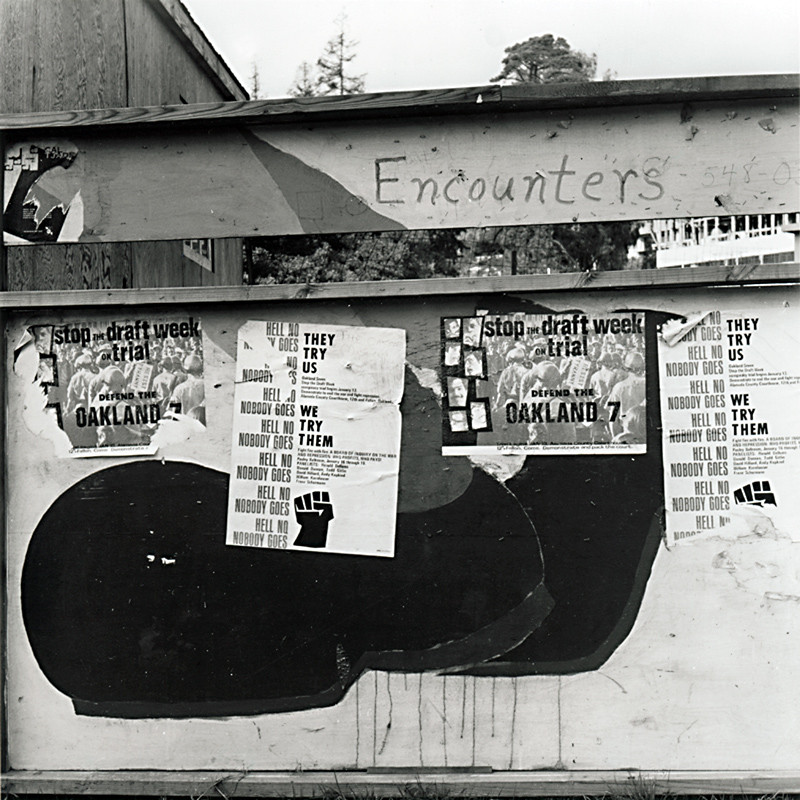

Here is a photo of those posters in the wild:

And this no-word poster that ended no words:

On the legal front, they had three lawyers.

Malcolm Burnstein was a partner of Robert Treuhaft and Doris Walker, all progressive and known for civil rights and civil liberties defense cases. (Hillary Clinton interned with the office in 1971). He was one of the chief lawyers of the Free Speech Movement and later defended Dan Siegel in his People’s Park bust.

Dick Hodge was in private practice representing musicians, novelists, artists, cartoonists, actors and directors including Richard Brautigan, William Hamilton, Steve Miller Band, Boz Scaggs, Kenny Loggins, Joy of Cooking, Commander Cody and many others. Governor Jerry Brown appointed him to the Alameda County Superior Court in 1981. He retired in 2001 and now works on alternative dispute resolution.

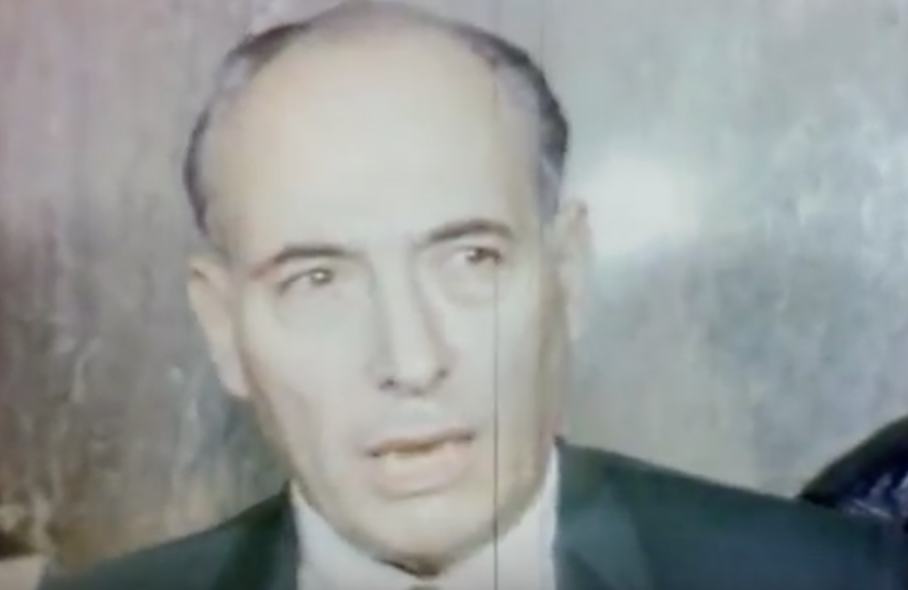

Charles Garry was the superstar of the group. He aggressively fought HUAC in the 1950s. At about the time of the Oakland Seven, he took on defense of Huey Newton for the Black Panther Party. Newton was charged with killing Oakland Police officer John Frey in 1967. When the Panthers asked Garry how good he was, it is reported that he said, “Perry Mason and I both win. The difference is that his clients are innocent.” That was good enough for the Panthers, who probably didn’t know that Mason in fact lost a few cases.

Here is a documentary about Garry’s work in the 60s.

To an extent that had not been seen with the Spock or Catonsville trials, witnesses in Oakland were allowed to explain their reasons for being at the Stop the Draft Week demonstration. The only qualification was that they had been present at the Induction Center. This was a giant leap towards the tactics in Chicago, where Judge Hoffman’s handling of the circus/trial earned him the title “the biggest Yippie of all.”

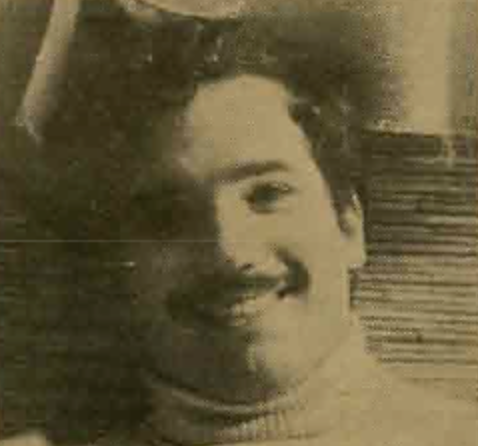

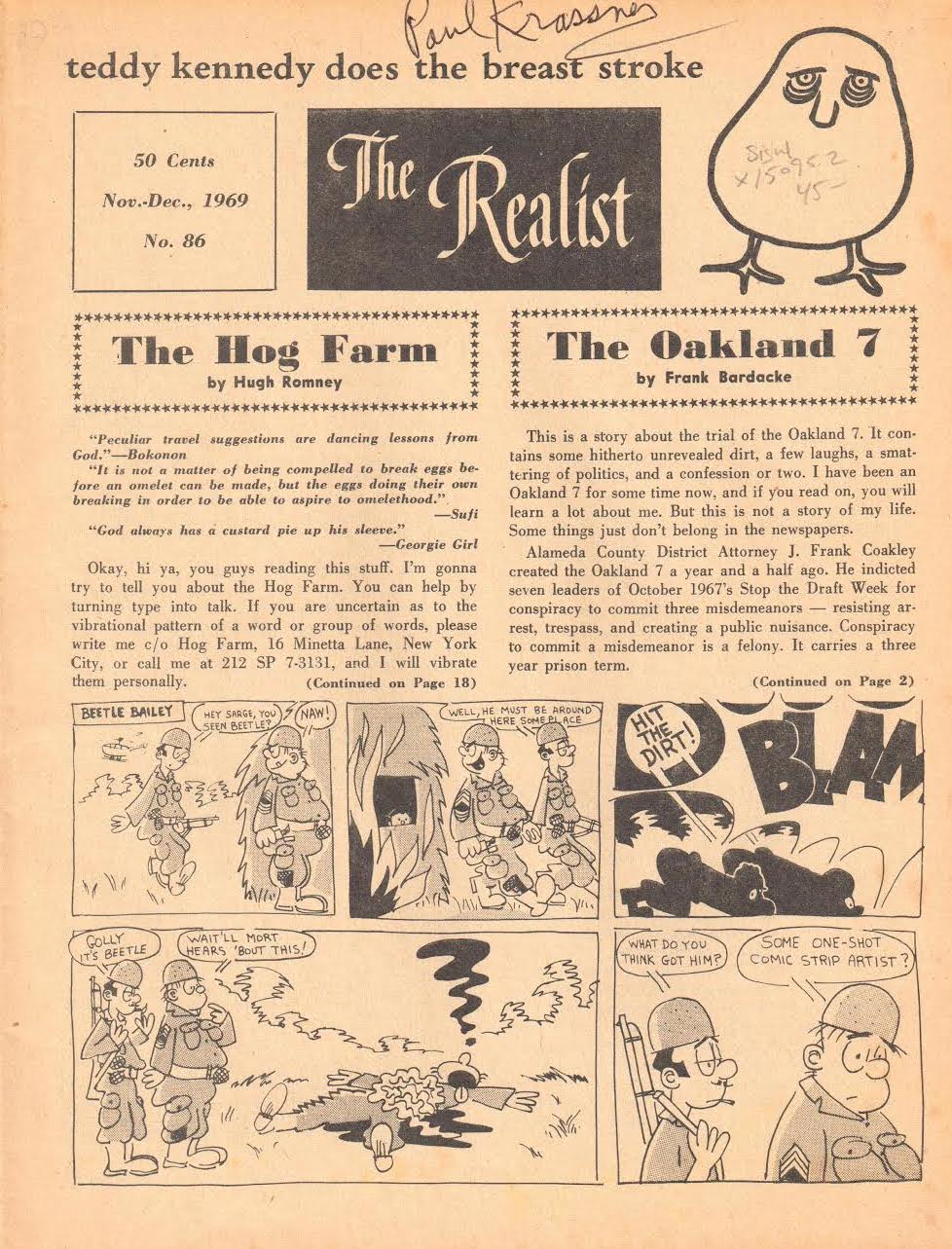

Defendant Reese Erlich wrote about the trial in The Realist. He went on to a career in journalism and writing.

The trial ended and the case went to the jury. The Seven waited for a verdict.

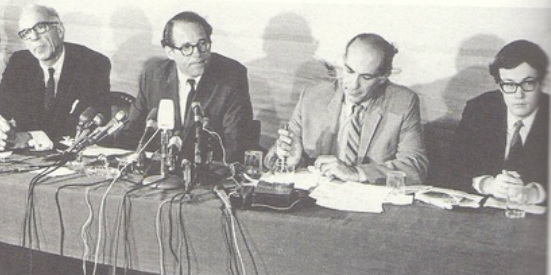

Left to right :SteveHamilton, Terence Cannon, Reese Erlich, Bob Mandel, Mike Smith, and Frank Bardacke. Photo from Ramparts courtesy of Frank Bardacke

The verdict came in – all seven of the Oakland Seven were acquitted “on the evening of Friday March 28 by four housewives, two Post Office clerks, a retired Colonel of the Marines, a statistician, a carpenter, an assembly-line inspector at General Motors, a defense plant tool and die maker, and the supervisor of construction in a radiation laboratory: by twelve people who the courtroom bailiff called ‘really a cross-section of life.’ Juror number 12, a huge blonde lady who wore a sailor suit and sucked Tropical Fruit Lifesavers, had held out three days for conviction.” (New York Review of Books, July 10, 1969). (Emphatic italics added).

After the trial, Bardacke himself wrote about the trial, also for The Realist (Nov.-Dec. 1969).

In his article, Bardacke gives considerable time to an analysis of Judge George W. Phillips. Bardacke dismisses Phillips as a liberal, but conceded that he “went out of his way to give good instructions to the jury. Without those instructions we might not have been acquitted.”

On the ultimate question, Bardacke was brutally honest: “We helped organize Stop the Draft Week. We were proud of it, and not about to deny it.”

The summer of 1968 saw escalated street fighting on Telegraph Avenue in July, August, and September. There were no defining issues at stake – it was an effort of street people and radicals to control territory, Telegraph Avenue. That summer saw increased police violence and the first widespread use of tear gas. The street fighters learned that tear gas was not that effective a deterrent outdoors. For the most part, the radicals and street people controlled the Avenue for long stretches at a time. This action would have an opposite and equal reaction the next summer during People’s Park, with the police anxious for payback.

The Eldridge Cleaver sit-ins in the fall of 1968 and Third World Liberation Front strike in early 1969 came and went. Bardacke, living in a house that called itself the Fisherman House, wasn’t particularly involved in either. The house motto was “You don’t need to be a fisherman to know when something stinks.” They made t-shirts with clenched fish.

And then came People’s Park. It was a movement that operated without leaders, although there were of course leaders. One of them was Bardacke. He was involved from the first or second planning meeting, through the building got the park, and through the battle for the park.

Before the park got going, Bardacke was approached by a tobacco heir who felt guilty about his wealth and wanted to donate a large sum to doing good things. Bardacke took the money and doled it out. A big chunk went to the Black Panthers. The Diggers in San Francisco wanted a commercial oven; part of the money went to the oven.

And then a big part of it went to the sod that transformed a slutted out, rutted out, junk-filled dirt lot into a green urban open space, People’s Park.

Between April 20th and May 15th 1969, thousands of people spontaneously transformed the soul-sucking eyesore of a vacant lot into a pleasant, relaxing park. Volunteers laid the tobacco-money sod, planted flowers and trees and bushes, built an amphitheater, laid out winding brick paths, and installed swings and play structures. Music was performed, children played, stew was cooked in garbage cans, wine was drunk and marijuana was smoked.

Bardacke remembers a series of chaotic meetings among the non-leadership leadership. These were men and women who for the most part had known each other for several years, united by their radical, non-sectarian politics and their embrace of aspects of the counterculture.

University officials at first ignored the transformation of the park, but soon asserted their ownership rights of possession, control, and exclusion.

The University did not seek an injunction in pursuit of its rights, and engaged in negotiations with an amorphous group of park activists. Bardacke says that he and his colleagues knew that the University would not let the park go on forever, but he didn’t imagine that Governor Reagan would escalate to brute armed force to reclaim the park.

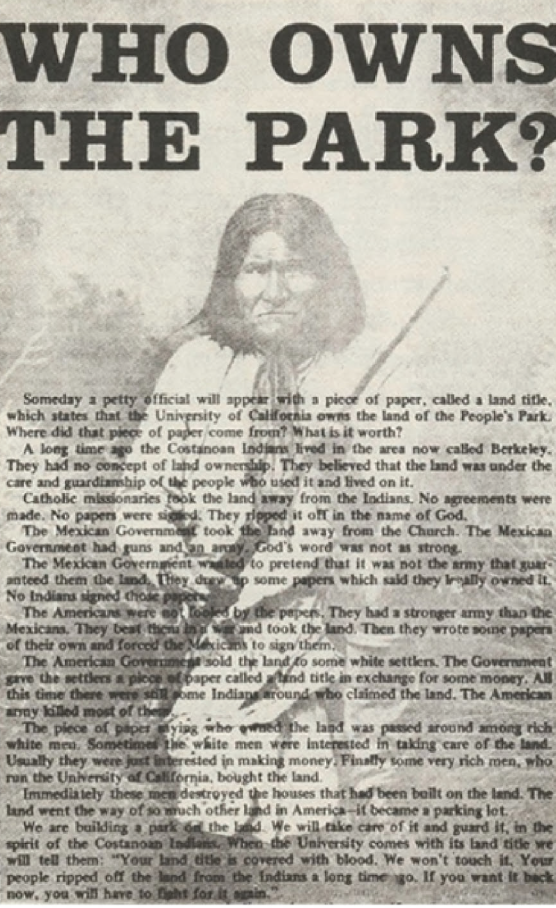

Before the University moved on the park, Bardacke composed one of the most famous pieces of literature that the counterculture would ever see.

The leaflet read:

Someday a petty official will appear with a piece of paper, called a land title, which states that the University of California owns the land of the People’s Park. Where did that piece of paper come from? What is it worth?

A long time ago the Costanoan Indians lived in the area now called Berkeley. They had no concept of land ownership. They believed that the land was under the care and guardianship of the people who used it and lived on it.

Catholic missionaries took the land away from the Indians. No agreements were made. No papers were signed. They ripped it off in the name of God.

The Mexican Government took the land away from the Church. The Mexican government had guns and an army. God’s word was not as strong.

The Mexican Government wanted to pretend that it was not the army that guaranteed them the land. They drew up some papers which said they legally owned it. No Indians signed those papers.

The Americans were not fooled by the papers. They had a stronger army than the Mexicans. They beat them in a war and took the land. Then they wrote some papers of their own and forced the Mexicans to sign them.

The American Government sold the land to some white settlers. The Government gave the settlers a piece of paper called a land title in exchange for some money. All this time there were still some Indians around who claimed the land. The American army killed most of them.

The piece of paper saying who owned the land was passed around among rich white men.

Sometimes the white men were interested in taking care of the land. Usually they were just interested in making money. Finally some very rich men, who run the University of California, bought the land.

Immediately these men destroyed the houses that had been built on the land. The land went the way of so much other land in America — it became a parking lot.

We are building a park on the land. We will take care of it and guard it, in the spirit of the Costanoan Indians. When the University comes with its land title we will tell them: “Your land title is covered with blood. We won’t touch it. Your people ripped off the land from the Indians a long time ago. If you want it back now, you will have to fight for it again. (Emphasis provided).

In the early morning of Thursday, May 15th, hundreds of law enforcement officers descended on People’s Park. All but a few of the campers there left voluntarily; three refused to leave and were arrested for trespass. The law enforcement oversaw the erection of a steel fence around the park; in the absence of any immediate reaction from park supporters, most of them left.

A scheduled noon rally at Sproul Plaza about the Middle East scheduled by Michael Lerner yielded to an impromptu People’s Park rally. The las speaker – who was not scheduled to be the last speaker – was Dan Siegel, incoming president of the student council. He suggested that one course of action was to “take the park,” an idea which sparked a strong reaction by the crowd of several thousand. They turned south and began marching down Telegraph Avenue towards the park.

The police, who were not prepared for a large march, halted the march before it could reach People’s Park. A fire hydrant was opened and the police responded with batons and tear gas.

South of Dwight Way on Telegraph Avenue, Alameda County Sheriff deputies ran out of tear gas and turned to shotguns, some loaded with non-lethal birdshot, some loaded with buckshot, which has an effective lethal range of 50 yards.

James Rector, an onlooker on a roof, was struck by buckshot and died four days later. Alan Blanchard, another onlooker on a roof, was struck in the face by birdshot and was permanently blinded. Dozens of marchers and bystanders were wounded by police shotguns, some shot in the back as they ran from the shooters.

In the aftermath, Governor Reagan established a strict curfew in Berkeley and called in more than 2,000 National Guard troops that occupied Berkeley for several weeks.

Bardacke was not in Berkeley for what instantly became known as Bloody Thursday. He was on a speaking tour that radical attorney Charles Garry put together to raise money for the Black Panthers, with either Bobby Seale or David Hilliard, both Black Panther leaders. He was in New York, staying in Jerry Rubin’s apartment. He came back to Berkeley immediately.

During the curfew, Bardacke was standing and watching one of the daily demonstrations that defied the curfew. Someone near him threw eggs at the police. The police identified Bardacke as the egg-thrower and came for him. He ran as fast as he could through South Campus streets and back yards, the police in pursuit. He collapsed on a front porch, pleading with the home owner to let him hide inside. He remembers to this day the look of sheer horror on her face. She didn’t let him in. He backed away and was soon in the hands of the police

The police grabbed him, threw him to the ground, and held a revolver to his head. They got him between two of them in the back seat of a police car and took turns jabbing his ribs. They told him to sing the national anthem. Bardacke remembers his reaction to the demand: “Man I started singing.” He was charged with a felony.

Refusing bail in the city jail until other demonstrators were released, Bardacke ended up missing the May 20th rally on Sproul Plaza when a low-flying National Guard Sikorsky U-19 helicopter sprayed CS gas on the plaza, and it quickly dispersed over the campus and Berkeley, causing acute respiratory distress, disorientation, temporary blindness and vomiting. The gas and dispersal technique were developed by the Stanford Research Institute for use in Vietnam.

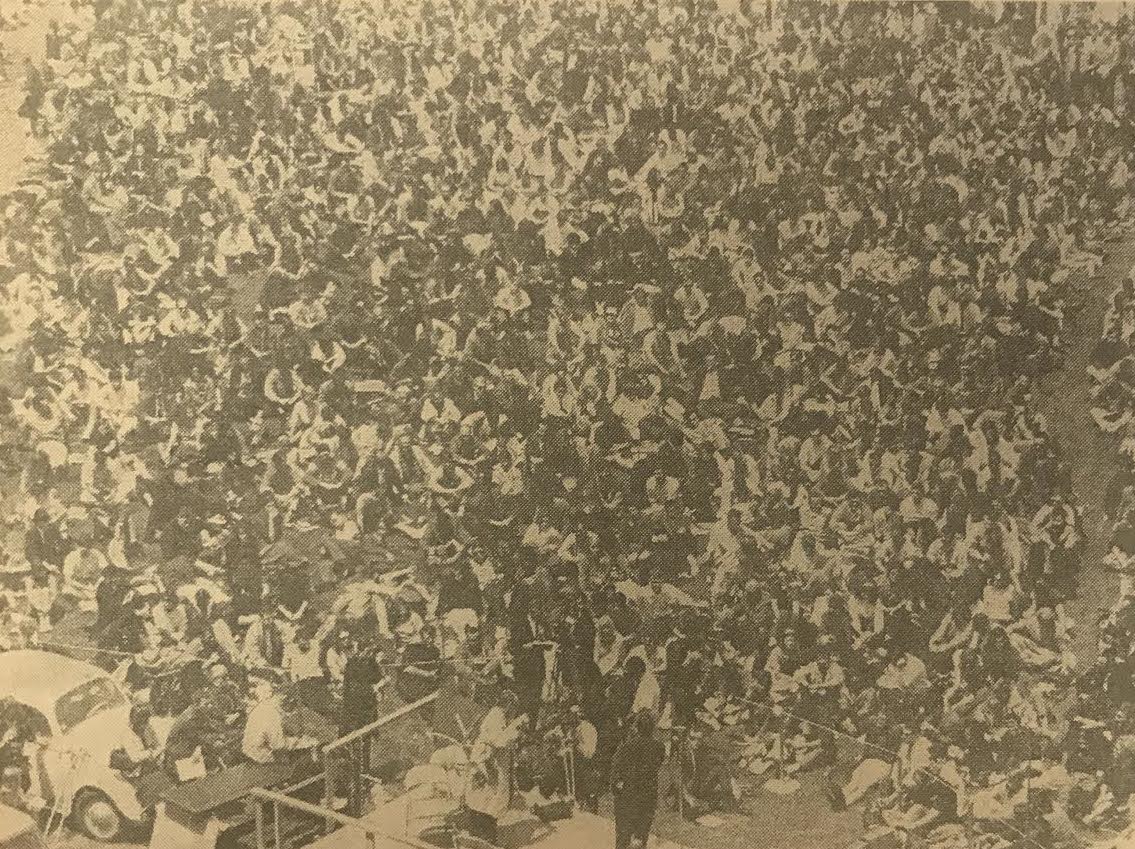

A large march was planned for Friday, May 30th. For the first time, the protests would include large contingents from outside Berkeley. Fearing confrontations and violence in the march, several Berkeley Movement elders stepped in. They brought in seasoned nonviolent activists such as Peter Bergel, who trained more than 700 peace marshals for the march. The peace organizers bought 30,000 daisies that they gave to the marchers.

There was no violence. The crowd of 30,000 was the largest ever assembled in a Berkeley protest. Bardacke was excited by the crowd. He remembers radios tuned to Tony Pigg’s show on KSAN blasting “For What It’s Worth” by the Buffalo Springfield.

“But we fucked up” says Bardacke. “It was wonderful, fine, but the park was still there. It was the right thing to do, but it didn’t get the park back.”

Over the summer of 1969, Bardacke was a leader in efforts to sustain the flames of People’s Park. He was notably involved in the People’s Pad movement, an effort to squat in an abandoned building in South Berkeley.

Reflecting on People’s Park 49 years later, Bardacke said: “There was no single motivation. It wasn’t a plot to lure the University into a fight, and the claim that Abbie Hoffman came to visit and suggested that we could do that is made up.

“I think that it’s more that the Telegraph street scene was feeling its oats. The parking lot was right behind the Med – you couldn’t avoid it. For Michael Delacour, it was not looking for a fight. He was about creating a culture that could take the land and make it added space, a resource for street people. For the Berkeley politico’s, it was ripping off corporation property and turning a parking lot into a park.

“We created another world in the belly of the beast. It’s hard in this cynical age to appreciate the optimism and excitement we felt. We chanted ‘The NLF has won’ and believed it. We believed that the only debate in this era of post-revolutionary culture would be on the type of socialism that we would have.”

And, briefly, then:

People’s Park actions continued over the summer of 1969. In the fall/winter, Bardacke went to Chicago to testify in the trial of the Chicago Seven. He tells this story: “The people who were going to testify that day had to wait in a room together before their turn to testify because they we weren’t supposed to hear each other’s testimony. There were about a dozen of us. Jessie Jackson was one. Pete Seeger was another. I was in my most hippy stage: I carried a harmonica which I used to play to pass the time. I was terrible. Anyway, I asked Seeger for a lesson. He was reluctant, but finally agreed. He said, ‘Play something.’ I played my best. His response was: ‘Have you ever listened to anybody play the harmonica?'”

Bardacke joined a Yippie delegation in New York that was planning to visit Cuba. He sensed that the Cubans were worried about the cultural excesses of the group, and without ever officially calling the trip off they placed the Yippies on perpetual hold. The trip didn’t happen.

In early 1970, Bardacke moved to Pacific Grove to work at a GI Coffee Shop in Seaside.

He quickly learned that while he and his fellow leftists knew a lot about the history of the Vietnam War, they knew nothing about the war itself. He says that there were “all kinds of misses” between the radical organizers of the coffee house and the mostly black soldiers.

Despite the problems, there were some good discussions and a few anti-war soldiers were able to get some help in their battles with the Brass. In one amusing highlight, Frank smuggled Jane Fonda into the barracks at Fort Order where she spoke to 50 or 60 soldiers.

He then worked for six seasons on a celery crew in the Salinas Valley, then taught at Watsonville Adult School for twenty-five years, and now teaches at CSU Monterey Bay. He is the author of Trampling out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers. It is an epically brilliant book. I talked with Frank a lot as he was writing it.

This story is as much about Berkeley as it is about Frank Bardacke. Yes, of course there were excesses, but they were excesses in opposition to excesses by the state – the over-reach of the University into the lives of students, the horror of the war in Vietnam that would not end, the tyranny of the draft, and the brutality of law enforcement.

Bardacke stood tall. He acted in a brave, proud, and unyielding manner. He acted without without retreating from confrontation, danger, or adversity. He did not seek personal fame or glory. He was guided by principle and informed by humor.

Berkeley was the epicenter of the youth movement, the political counterculture, and resistance to the war in Vietnam. Mistakes were made, and regretted, and learned from. The struggle was real.

I asked my friend about this Bardacke post.

He pulled out a photograph that he keeps in his wallet, taken during the Free Speech Movement. In this photograph he is talking about the original Port Huron Statement, not the compromised second draft, to leaders of the Free Speech Movement. It was a defining moment in his life. He claims that he had been at Port Huron and that the reference to the use of the English language in this hemisphere as evidence of racism was his idea.

My friend missed People’s Park – he was in Delano living with Gabby, who was about to step in it and get shipped out by Cesar to the grape boycott in Philadelphia as punishment, but it is a righteous moment as far as he is concerned.

What does he think about this account of Frank Bardacke?

Great piece! I was one of the FSM lawyers, and was a participant in much of what was going on.

Times to remember.

I came to California in 73 and to Berkeley in 77. This was such a good read to fill up some of history I missed. Thank you.

Loved the article. Sent to me by pal Joe Blum who was editor of The Movement after Terry Cannon. Glad to see my photo of Jack Weinberg, Michael Lerner, Marvin Garson on Sproul Hall Steps in fall of 1964. Would have loved a photo credit; not sure where you found it; very happy its included. Its on my website: michaelgaylordjames.com

Onward Comrades,

Mike James FSM vet

Fixed. It is a truly great photo. Tom

I know the title of this site is Quirky Berkeley. But so much of Frank Bardake’s extraordinary energy was devoted to unheralded organizing of agricultural workers in less glittering parts of California. I wish we could read more about that. Still thanks for collecting all of this.

(I also spy a rare photo of my former husband Marvin Garson)

Frank and Nancy were Mr. & Mrs. Berkeley.

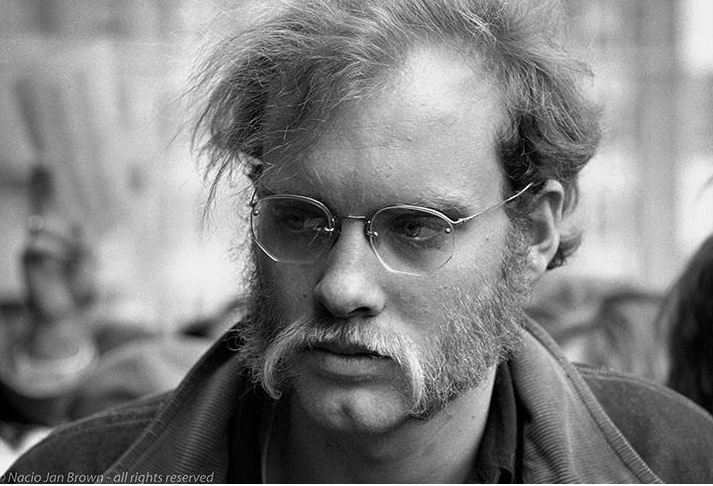

Nacio Jan Brown’s wonderful photo of an October 1967 “Stop the Draft Week” rally was shot at Lower Sproul Plaza, directly in front of Zellerbach Hall. If you look closely, you’ll see that it was still under construction. Note that the second-floor windows had yet to be installed. The building wouldn’t be completed until May 1968.

I’m surprised that this interesting article didn’t mention that fact that Lowndes County, Ala., where my hero Terry Cannon worked as a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) field worker, would later become the birthplace of both Black Power, a modern, secular variant of the two-century-old tradition of black nationalism, or African American self-determination, and the first Black Panther party, formally known as the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LFCO). The party was co-founded by SNCC field worker (and later chair) Kwame Ture, then still known as Stokely Carmichael.

(Ture accepted his African name in 1968 from two of modern Africa’s greatest leaders: deposed Ghanian President and Guinean Co-President Osagyefo (“Redeemer”) Kwame Nkrumah and Guinean Co-President Sékou Touré. Thus, he should never be called Stokely Carmichael after this date, anymore than Muhammad Ali should be called Cassius Clay after March 6, 1964, when Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad rechristened him.)