When I set out to meet Julia Vinograd, I met Dorrit Geshuri who manages the apartment house were Julia lived. I wrote about Julia and then I wrote about Dorrit. And then Dorrit introduced me to Emmanuel Catarino Montoya. He is an inspiring artist and beyond that a powerful cultural force.

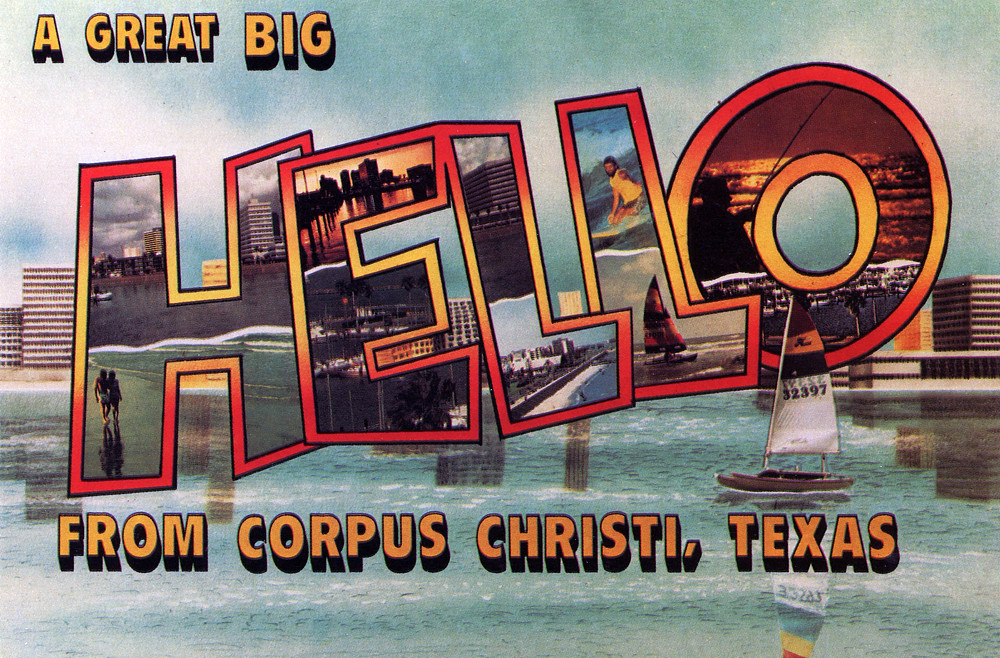

Montoya was born and lived the first 12 years of his life in Corpus Christi, Texas.

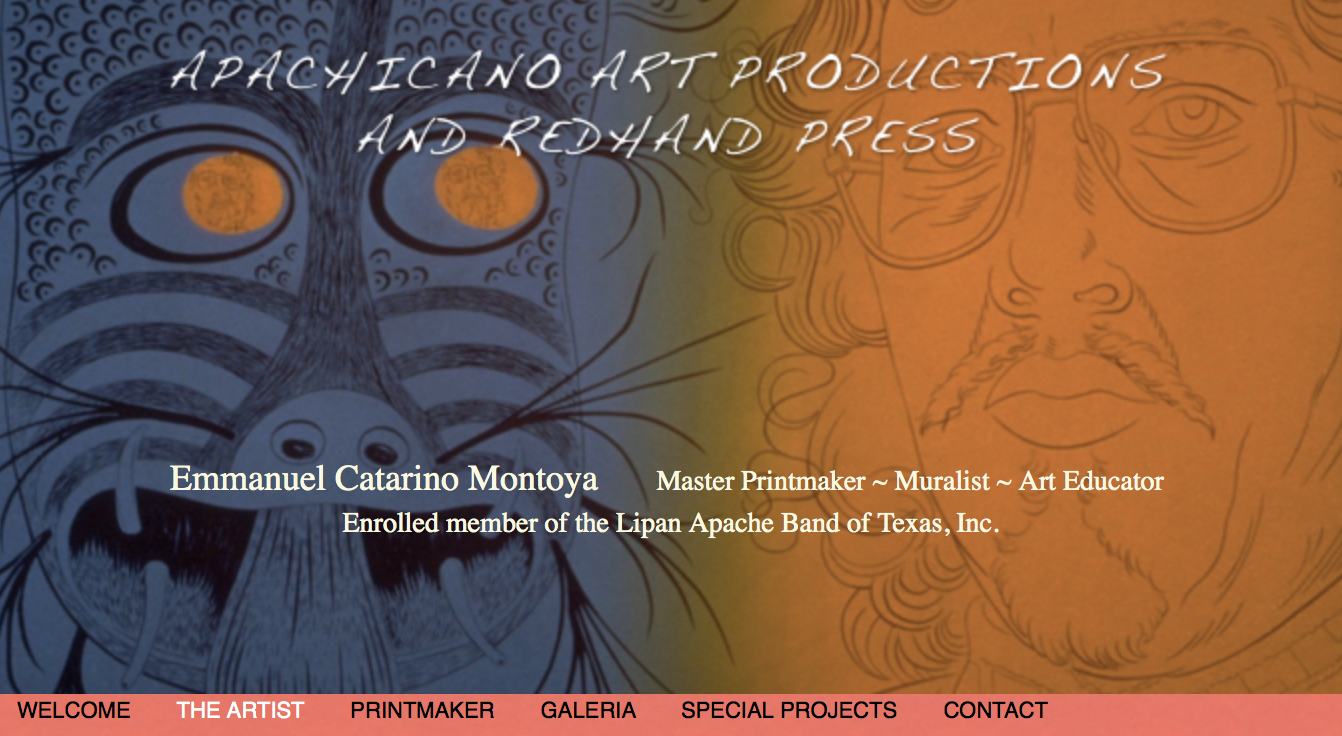

He is of Lipan Apache and Mexican heritage. The Lipan Apache Band of Texas, in which Montoya is enrolled, has over 745 members and is composed of the Cúelcahén Ndé (People of the Tall Grass), Tú é diné Ndé (Tough People of the Desert), Tú sìs Ndé (Big Water People), Tas steé be glui Ndé (Rock Tied to Head People), Buií gl un Ndé (Many Necklaces People), and Zuá Zuá Ndé (People of the Lava Beds) that has continuously lived in Texas since First Contact in 1528. He has coined the term “Apachicano” to described his mixed heritage.

His mother’s grandmother, who lived from 1870 into the 1930s, was born in Brownsville, Texas, and live there before moving to Corpus. They called her “Mama Jesusa.” Although the story was passed down from family member to family member that she was Apache, she was not a member of Lipan Apache band. This photo of her could be found in the homes of Montoya’s mother’s relatives.

He and his brother researched their family’s Apache roots in Texas in 1992, interviewing family members and retrieving birth and death certificates.

In 1993, Montoya’s mother recalled her childhood in this simple but detailed sketch of the house where she lived as a child with her family.

Montoya’s brother Ikoshy (born Timoteo) Montoya is an artist as well. He has embraced his Apache heritage in a bold and beautiful way

Montoya: “In the 1950s my Uncle Joe, my papa ́s older brother owned a gas station and sold auto parts. Before my papa began his own gas station business in Corpus, Uncle Joe would employ him part time during the summer time. He would load up a step van with auto parts and my papa would sell them while raveling all over South Texas. I would accompany him bringing with us a lunch that my mama would pack for us. I would be there with him at the gas station, pumping gas or ̈guarding ̈ the cash register.”

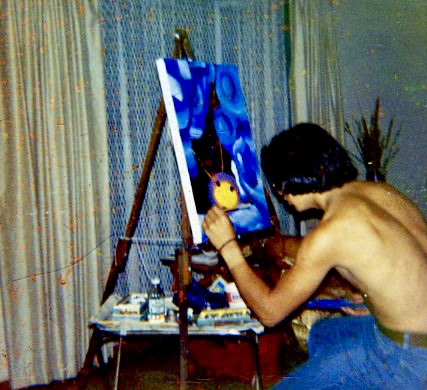

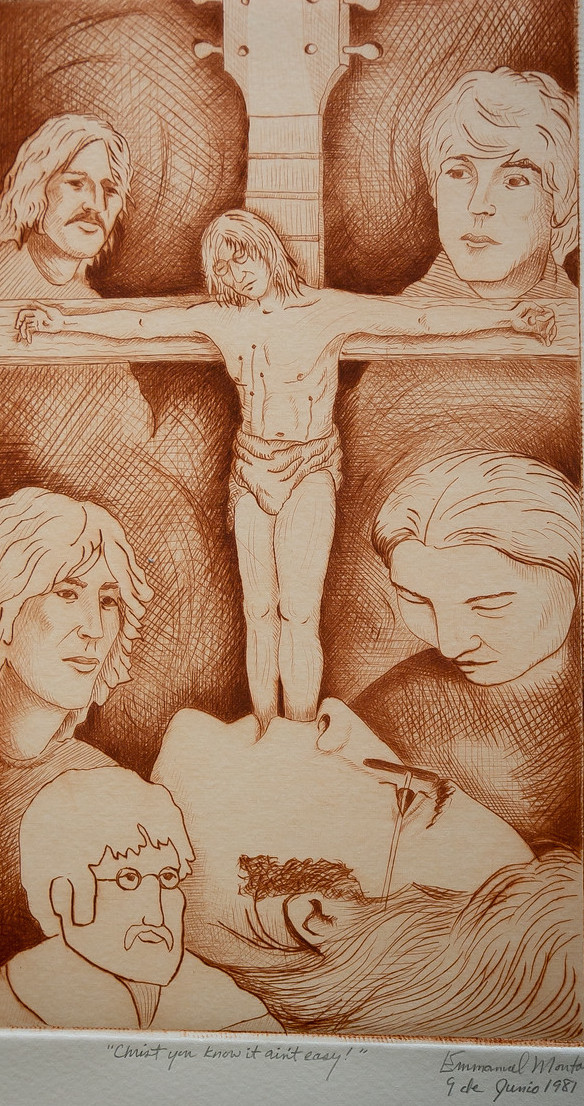

When Montoya was 12 his family moved to San Francisco. His father drove his 1957 Chevrolet Biscayne to San Francisco with Montoya along for the ride, in charge of the maps. His mother and baby brother and three sisters followed a few months later. From 1964 to 1969, while living in the heart of a cultural renaissance, he experienced what he calls a “profound and vibrant awakening filled with music and art.” These years in school and at home proved a most creative time for him. And his art expressed

He went to Balboa High School through 11th grade; his family moved to Palo Alto. He continued his art studies at Gunn Senior High School and then Foothill Junior College for two years.

Montoya would bring home canvasses that he found discarded in the Art Department at school.

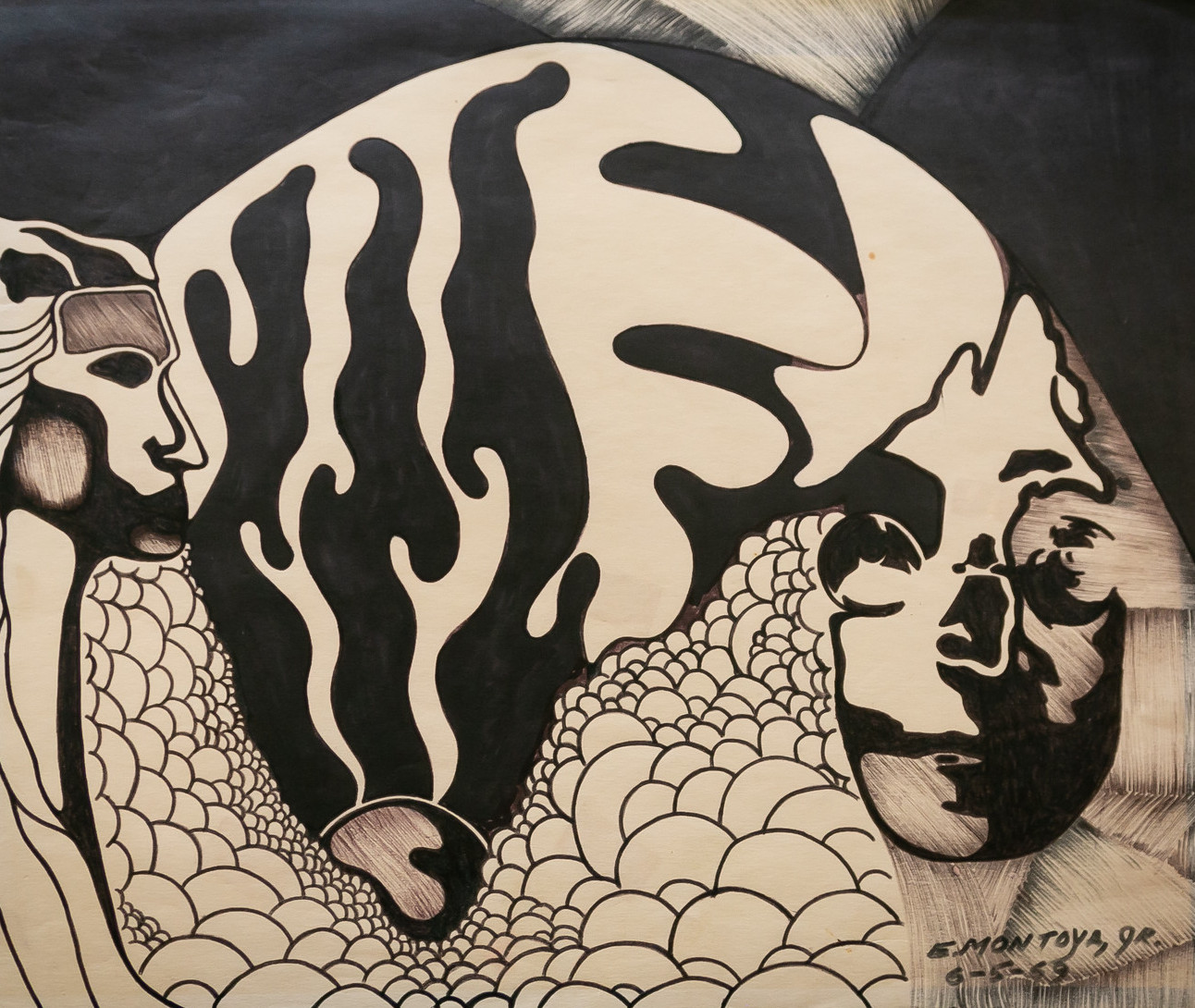

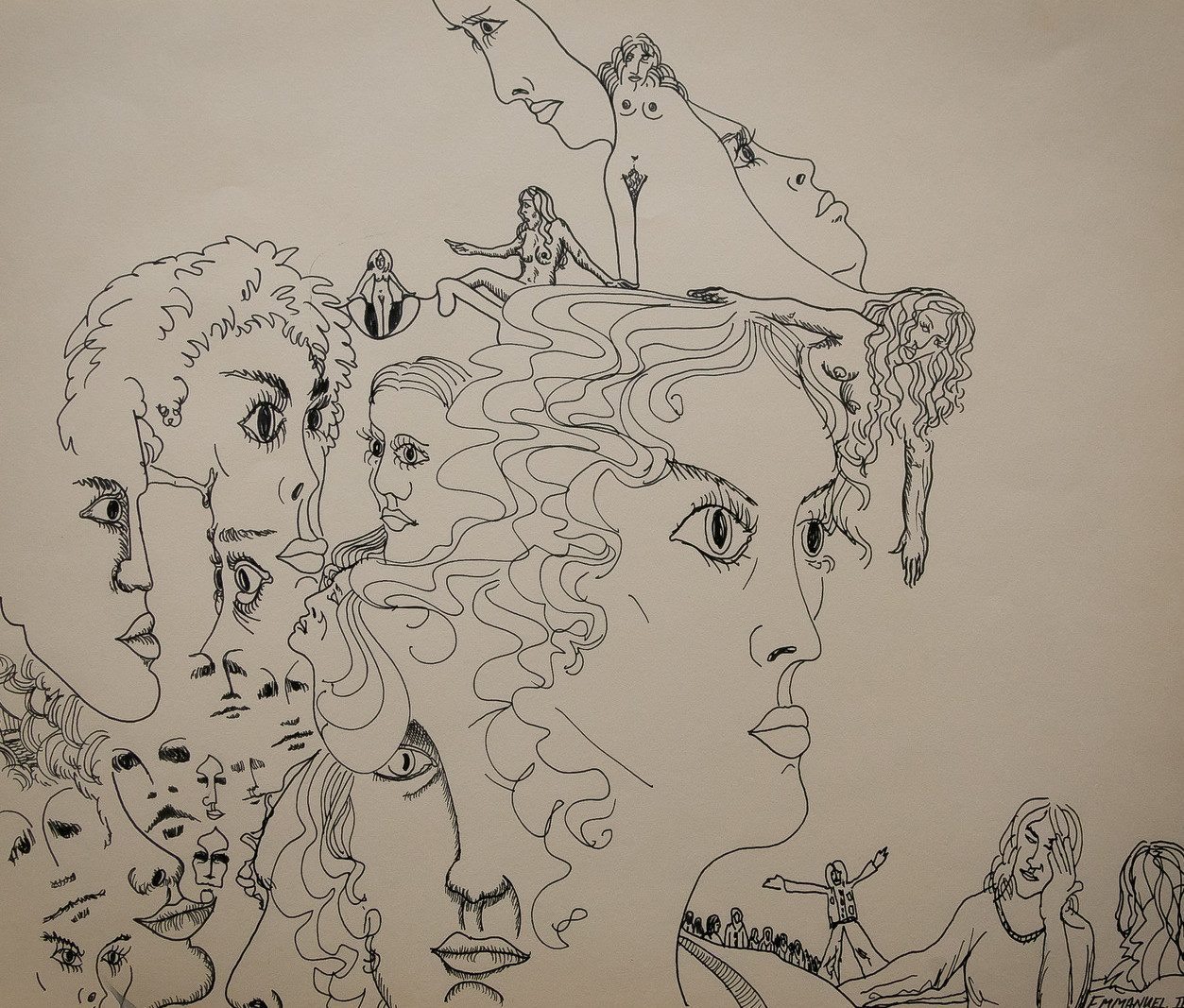

More early art:

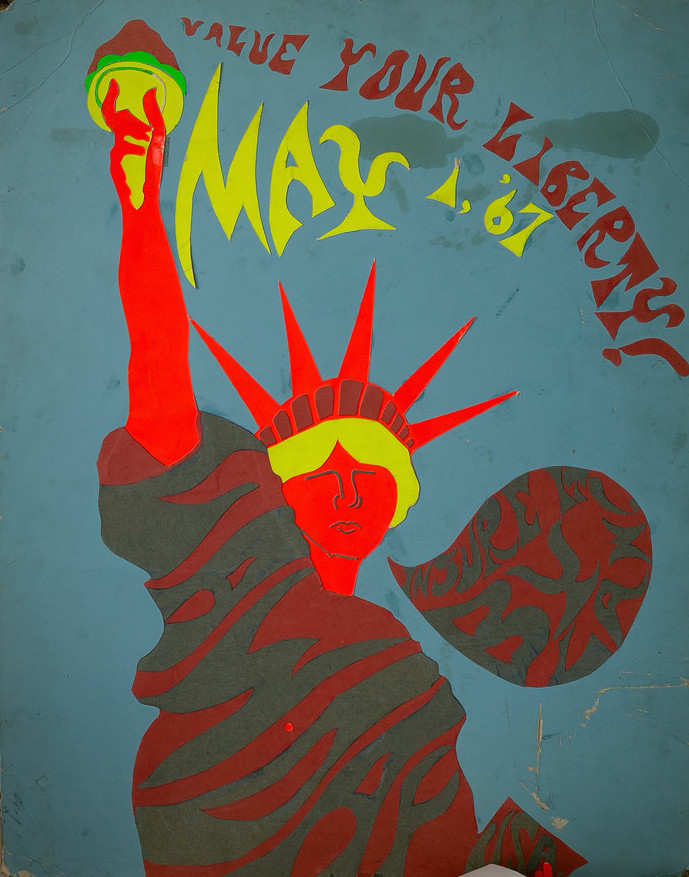

Montoya entered this in a poster contest at James Denman Junior High School. He won a $75 savings bond as the first place prize.

Montoya made this in 1965, impressed with the hills of San Francisco.

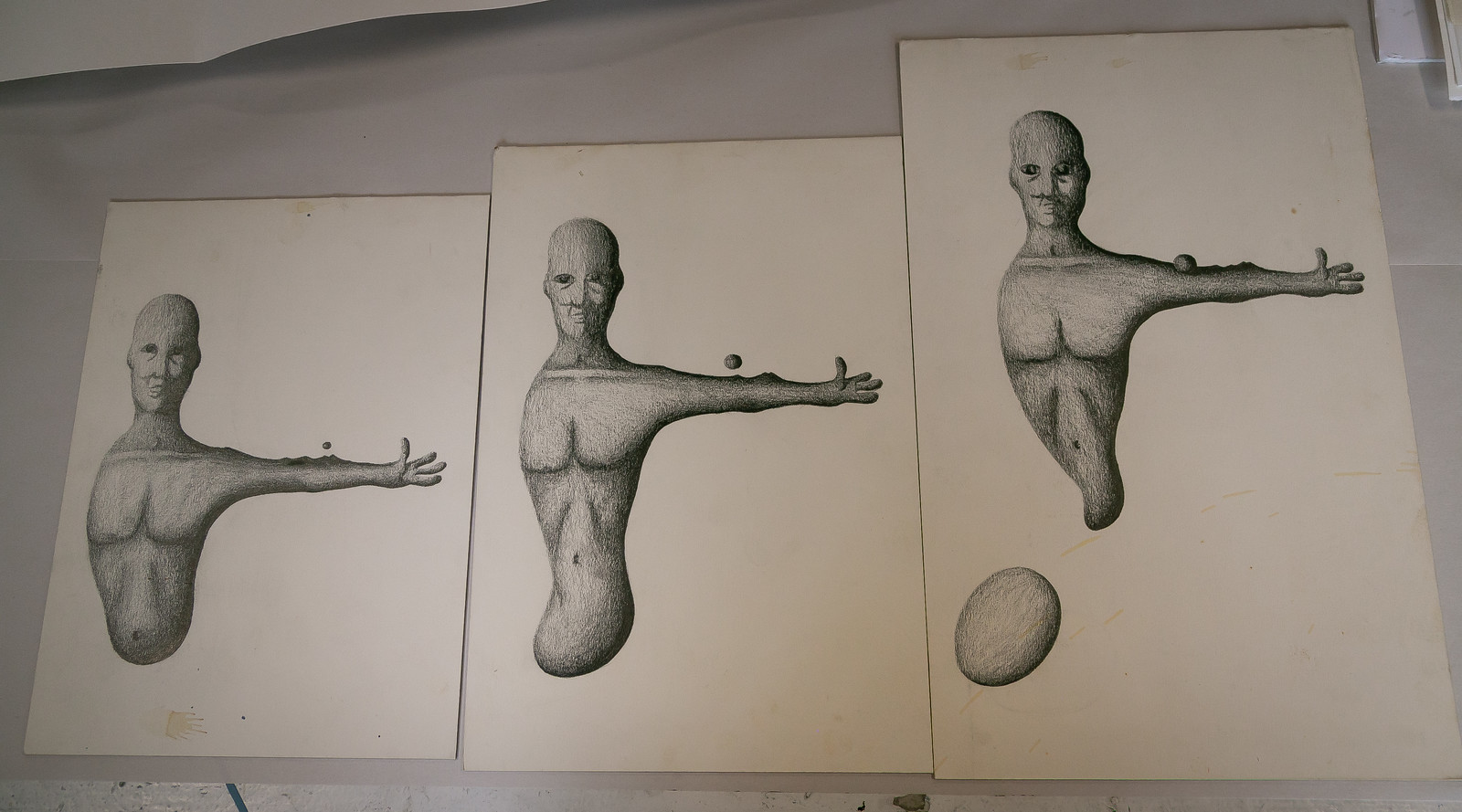

This triptec was a school project – giving birth to the egg as the moon rises on his arm.

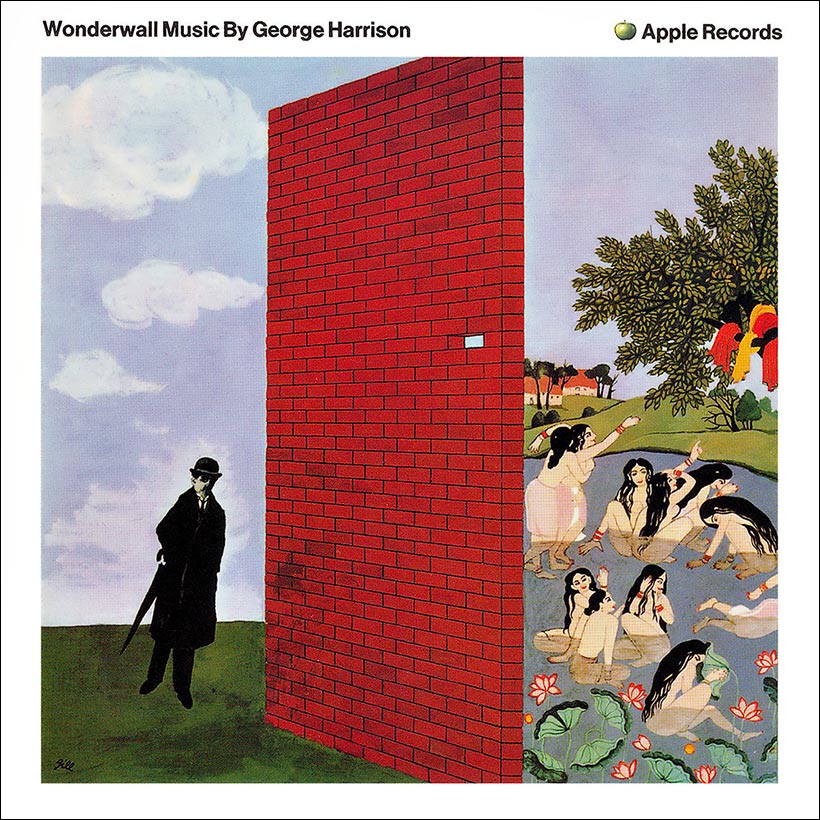

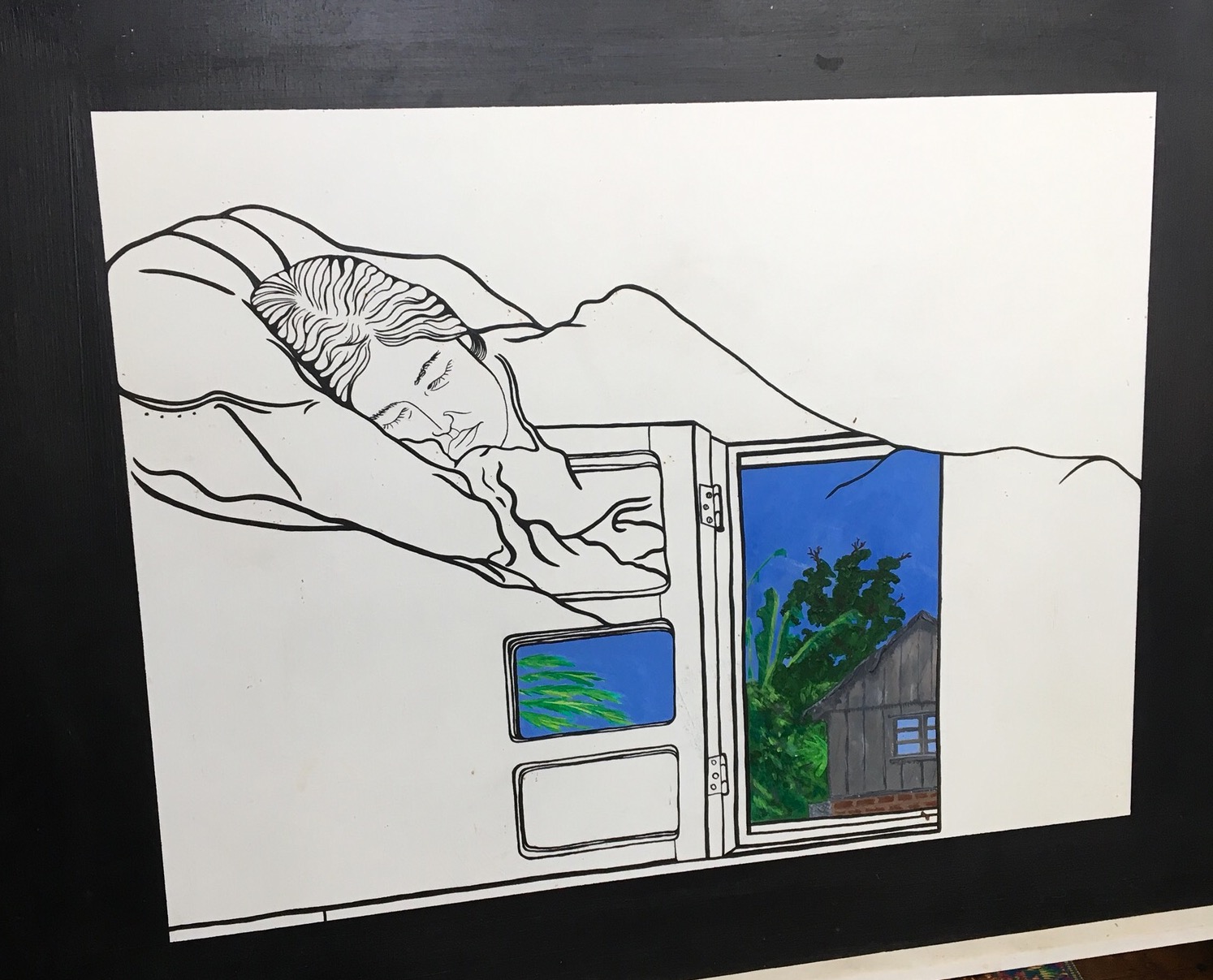

This water color done with poster paint on illustration board was his response to an assignment to design an album cover.

Montoya had recently bought George Harrison’s 1968 solo album Wonderwall.

Montoya had recently bought George Harrison’s 1968 solo album Wonderwall.

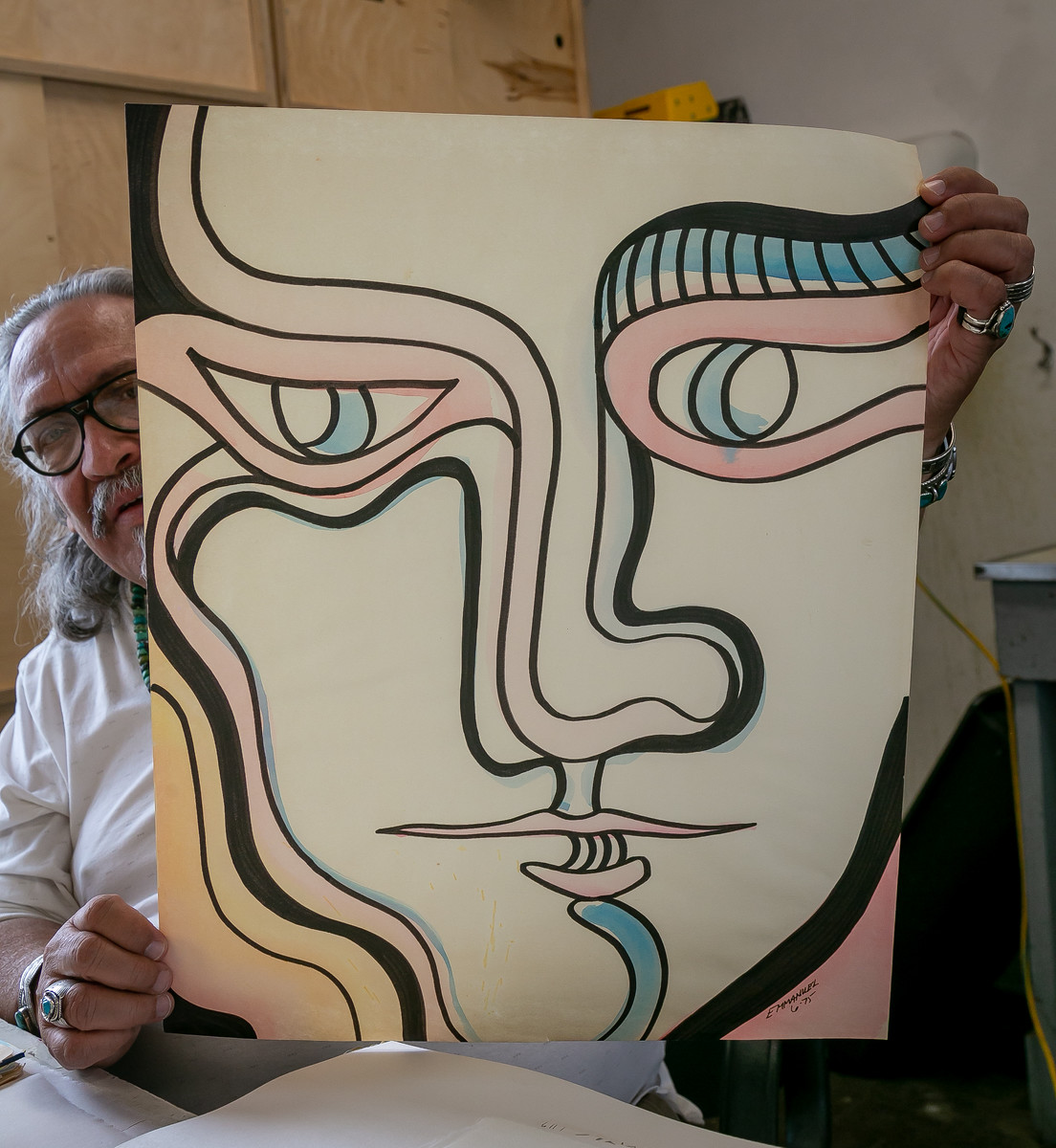

When he made this, Montoya was experimenting with the human face in mixed media. He cites his inspiration for this as the cultural renaissance happening in San Francisco in the late 1960s.

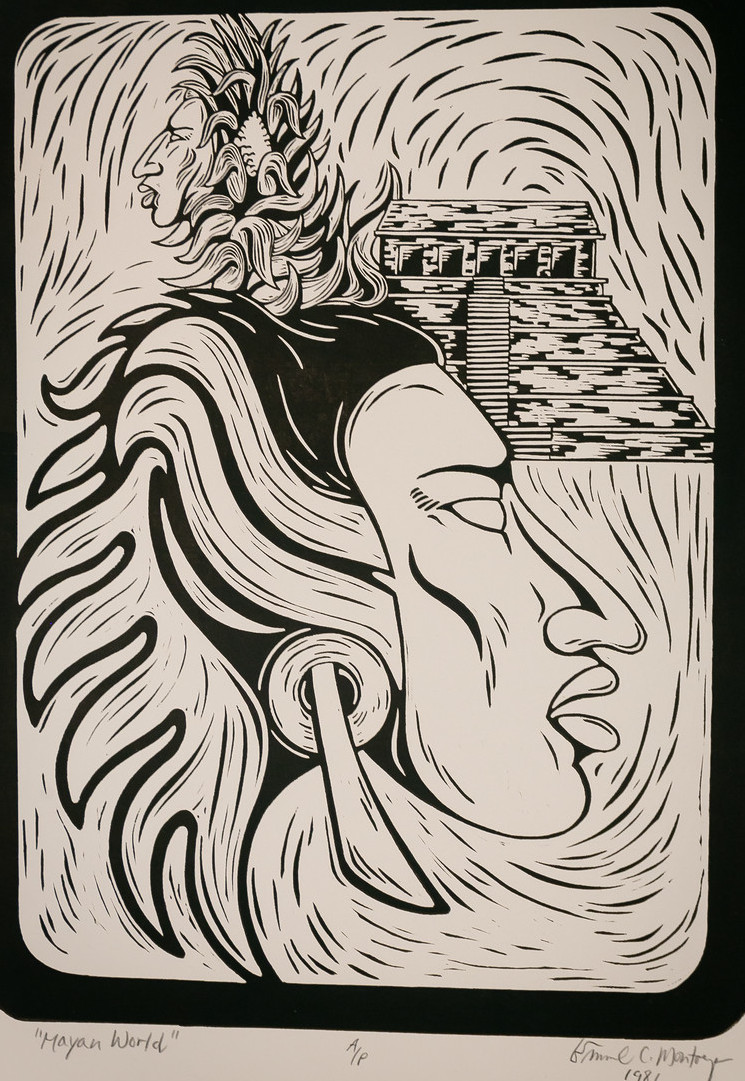

“Mayan World” was Montoya’s first linocut, produced at City College in 1981. He had experimented with the medium while at Gunn high.

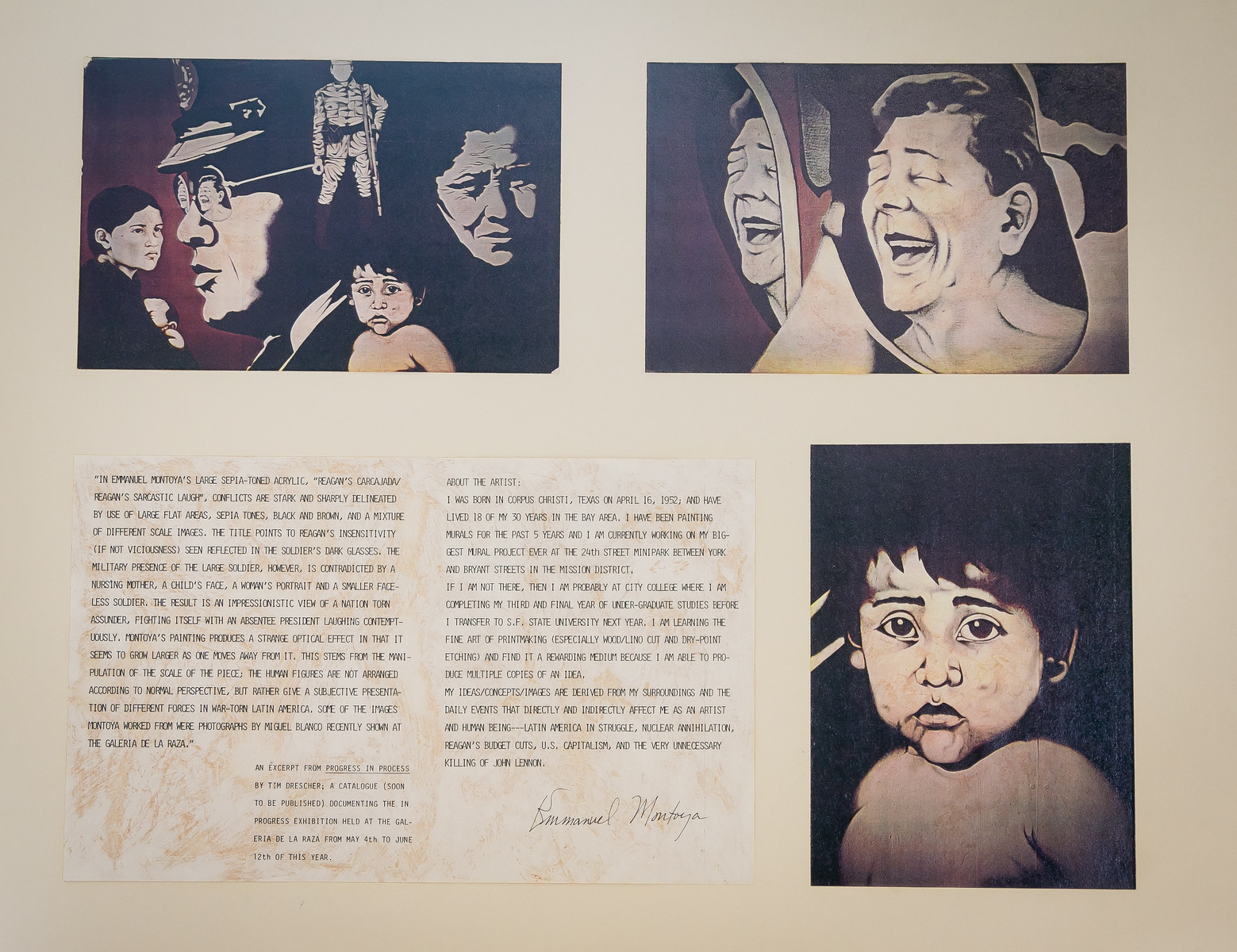

After graduating he studied commercial art at Foothill Community College for a year and studying for three years at the City College of San Francisco, Montoya earned a Bachelor of Arts in printmaking (1986) and Master of Fine Arts (1991) in printmaking at San Francisco State University.

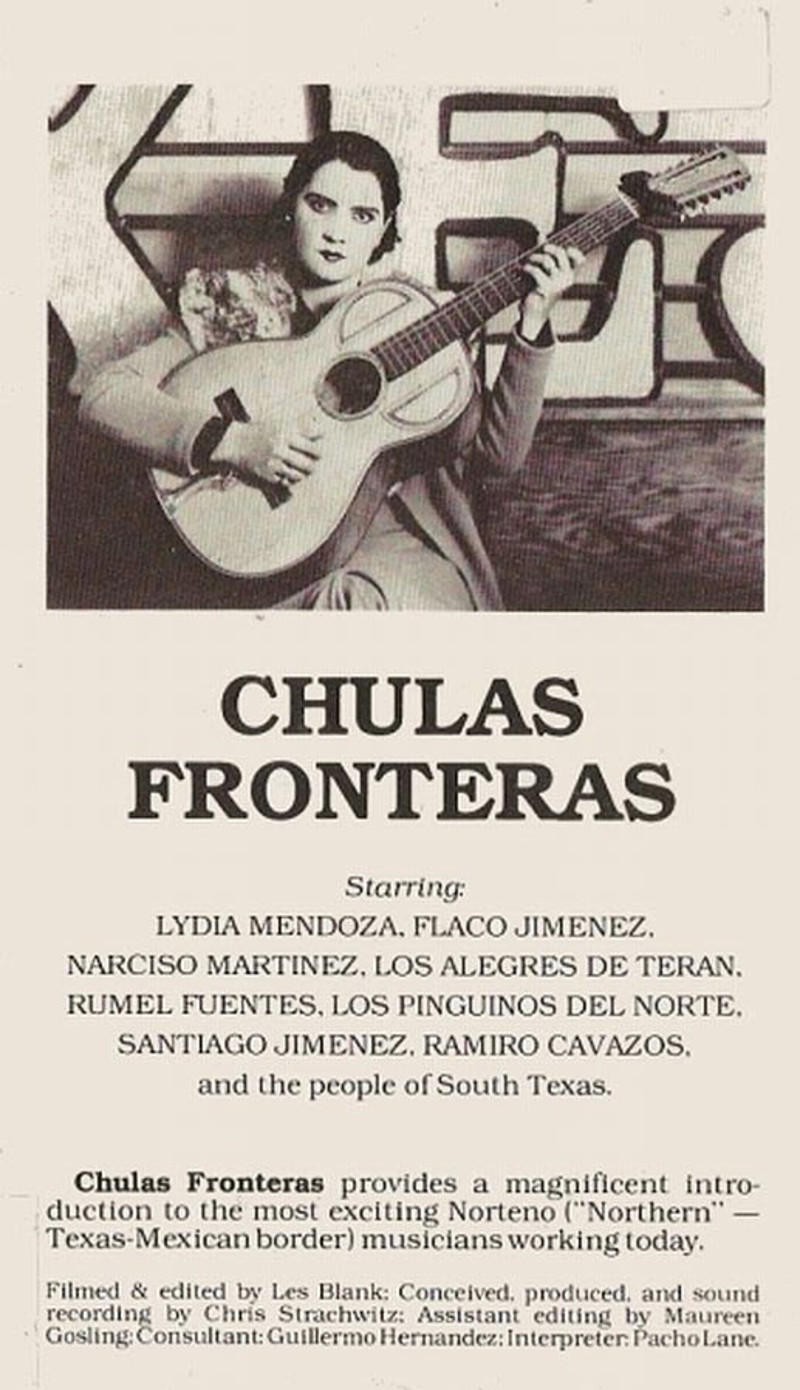

Montoya did not embrace his Chicano identity until the mid 1970s. Seeing Les Blank’s 1976 Chulas Fronteras, a 1976 documentary film that tells the story of the norteño or conjunto music played on both sides of the Mexico–Texas border, stirred his interest in Chicano culture. The visual presentation of migrant farm workers and their traditional music brought on a wave of memories of the years he lived in Corpus Christi.

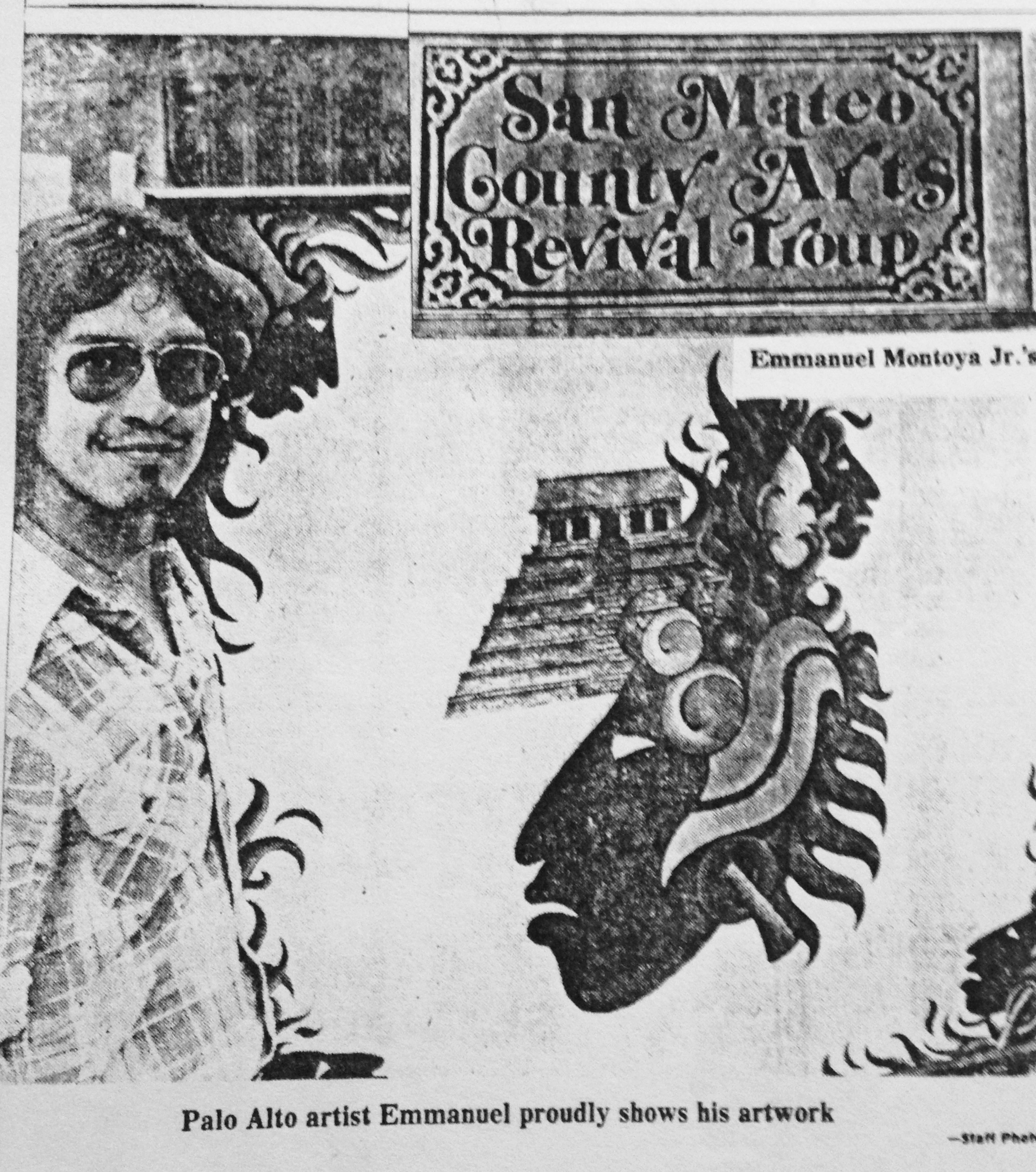

He was a CETA employee of the San Mateo Arts Council for a few years, and he began to be drawn to the cultural and mural scene in the Mission.

In 1976, Montoya also saw the book Toward a People’s Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement by Eva Crockcroft, John Pitman Weber, and James Cockcroft. Montoya’s sense of cultural consciousness was exploding.

In 1979 he moved into the heart of the Mission, 24th and Hampshire. He documented murals with photographs and worked in silk screen at La Raza Grafica.

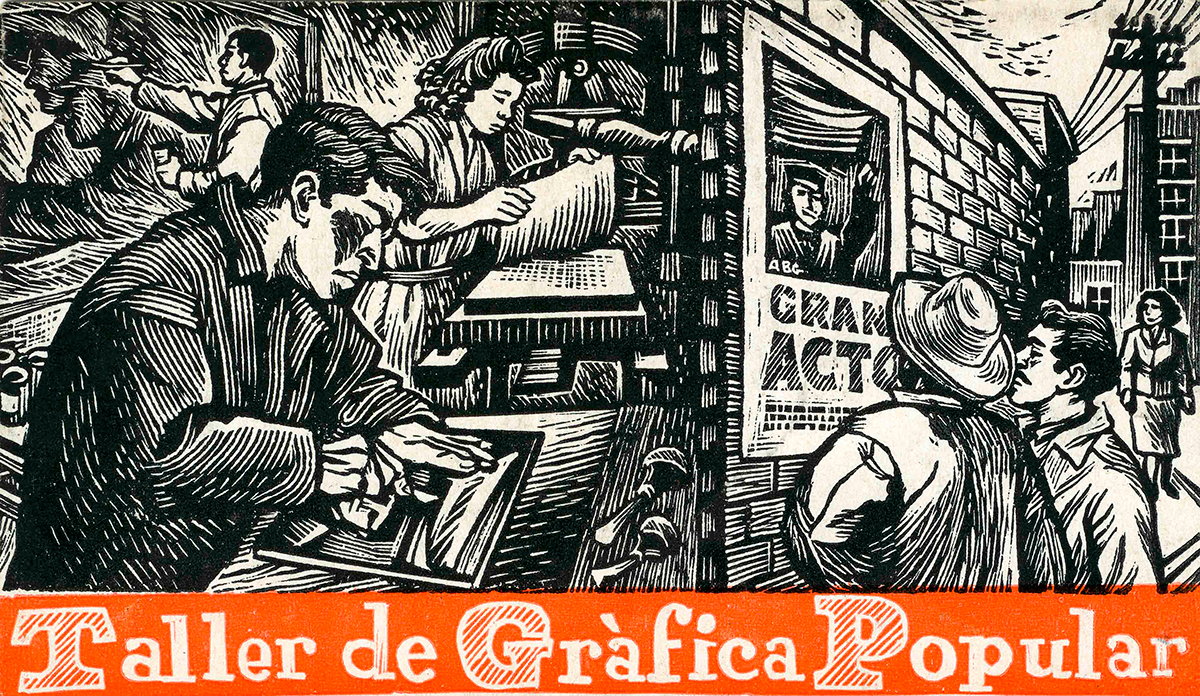

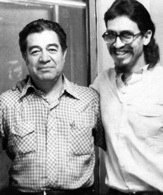

In 1984, Montoya went to Mexico City (“El Nuevo Tenochtitlan,” as Beltran called it, and met Alberto Beltrán García (1923-2002), with whom he had corresponded for several years. Montoya: “In 1978 Mexican muralist Gilberto Romero was visiting the Bay Area. Romero heard of my interest in Mexican printmaking. He introduced me to Alberto Beltran, well-known printmaker, historian, and political cartoonist and member of El Taller de la Grafica Popular. And so began a friendship and mentorship for some 22 years. We corresponded and chatted over the phone, exchanging artwork and books,”

Beltran, who was a graphic artist and painter known principally for his illustrations and political cartoons, became a mentor for Montoya.

Beltran was a member of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (“People’s Graphic Workshop”) an artist’s print collective founded in 1937 that was was primarily concerned with using art to advance revolutionary social causes. Through Beltran, Montoya met a number of Mexican graphic artists who informed his work. Montoya visited Beltran several more times and they corresponded until Beltran’s death.

Beltran was a member of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (“People’s Graphic Workshop”) an artist’s print collective founded in 1937 that was was primarily concerned with using art to advance revolutionary social causes. Through Beltran, Montoya met a number of Mexican graphic artists who informed his work. Montoya visited Beltran several more times and they corresponded until Beltran’s death.

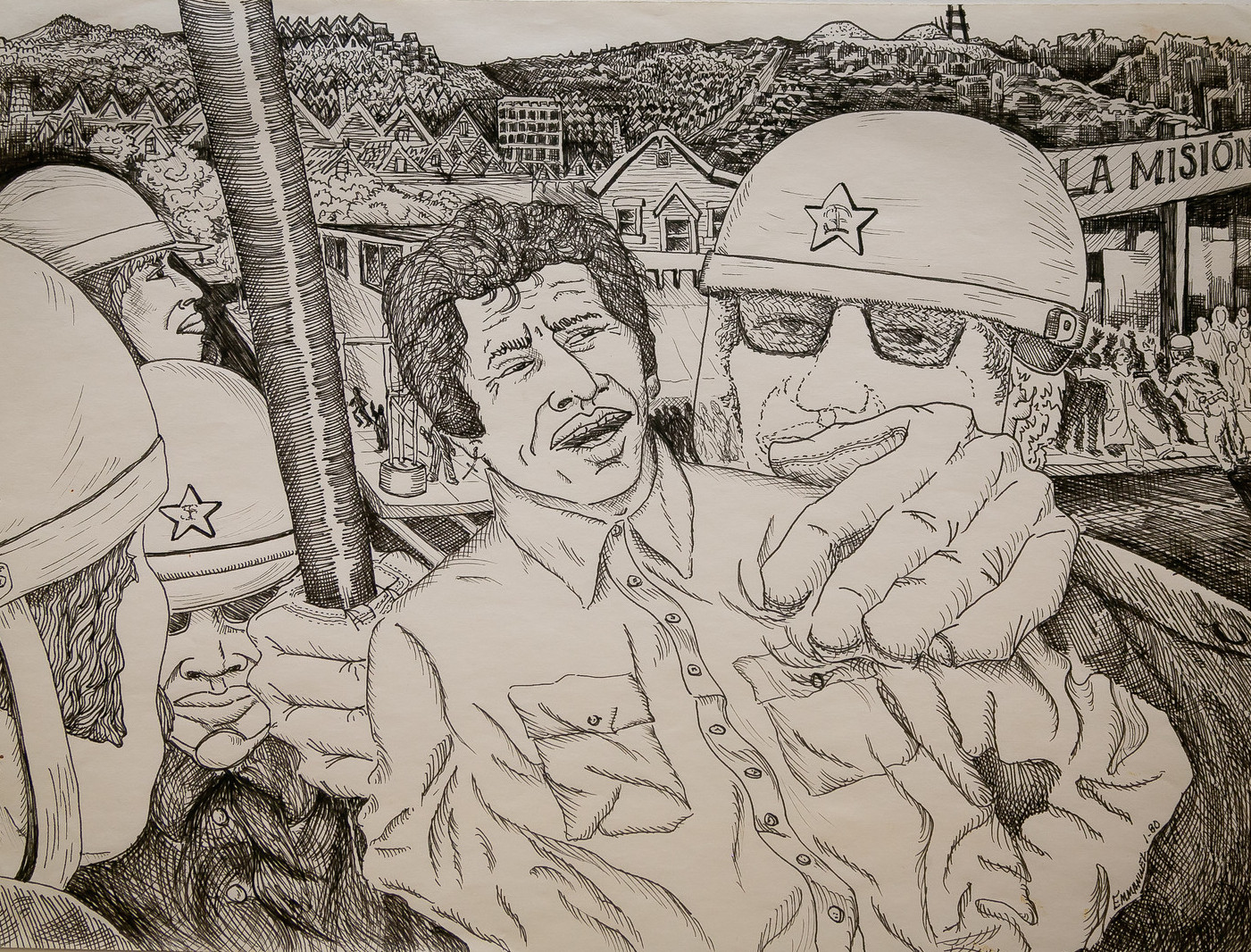

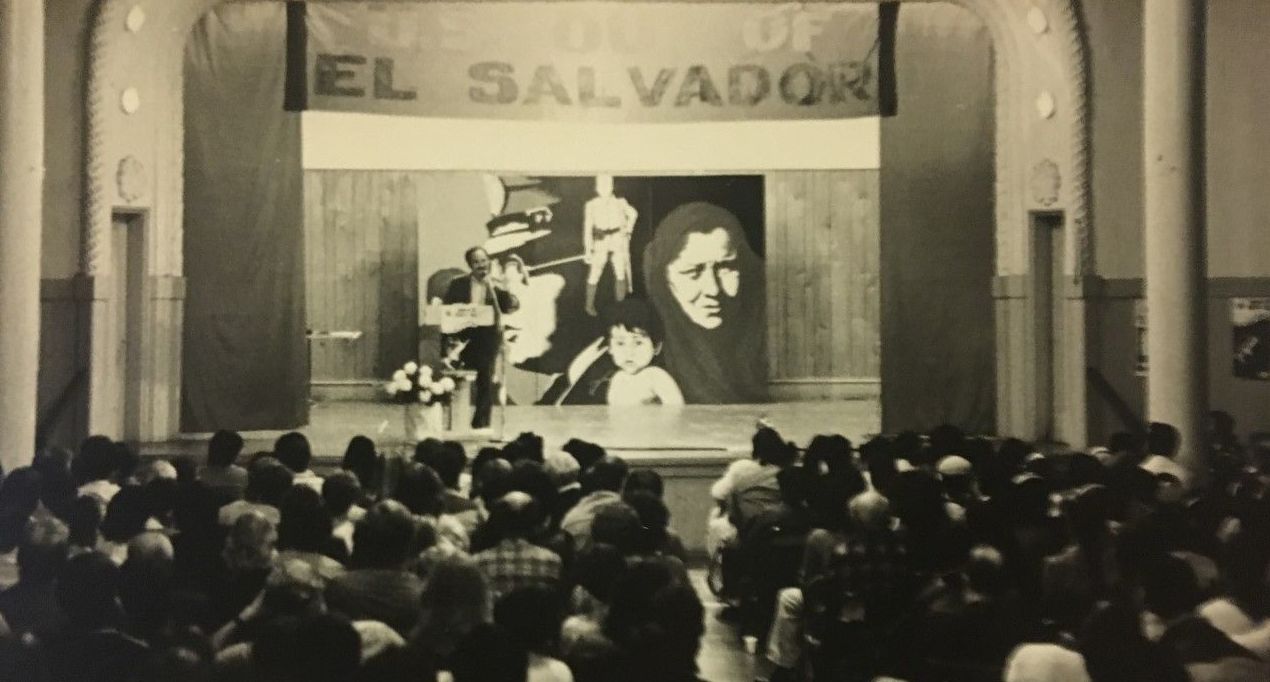

This mural was part of an “Anti-US Out of El Salvador” public gathering in the Mission in September 1983. Details of the mural:

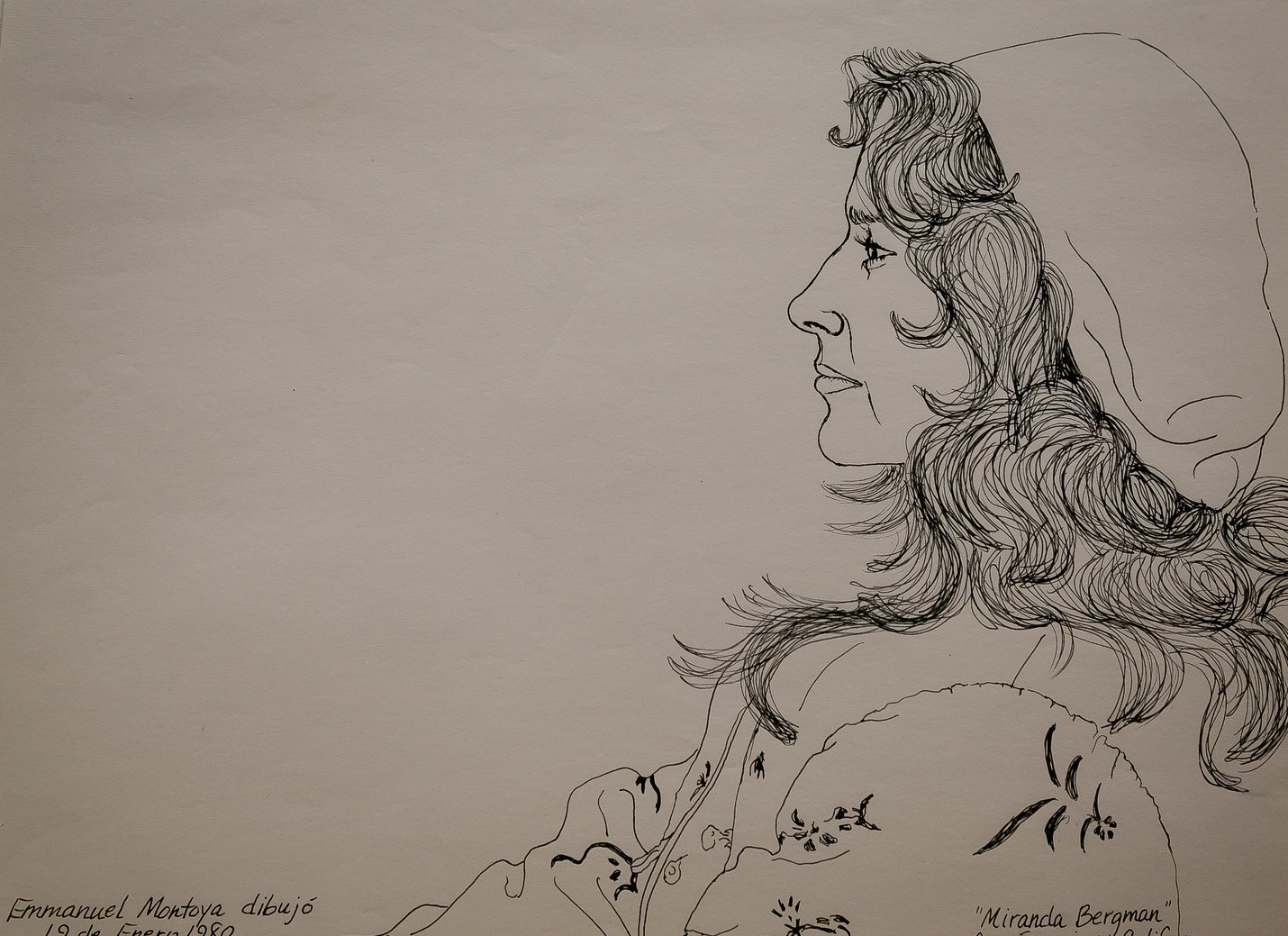

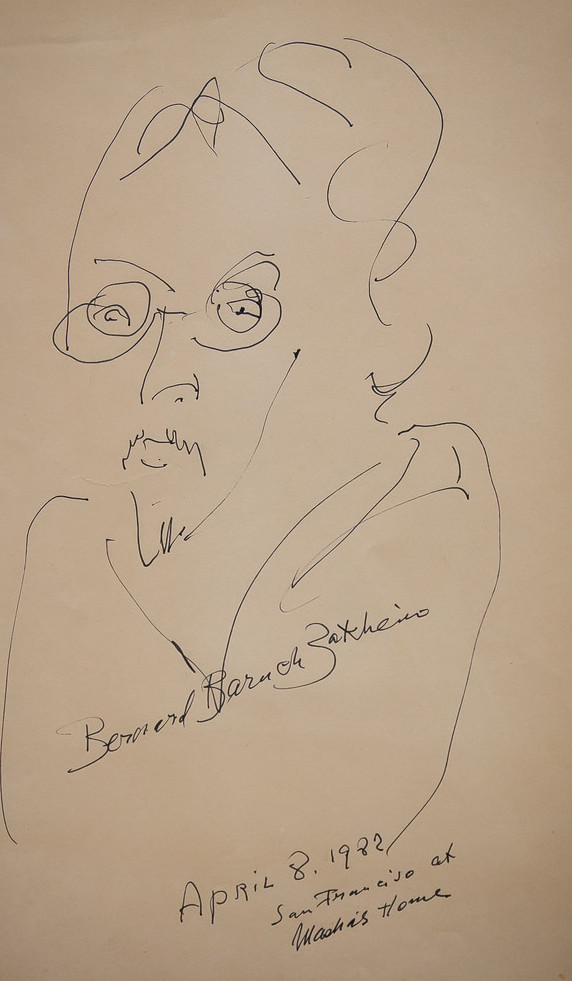

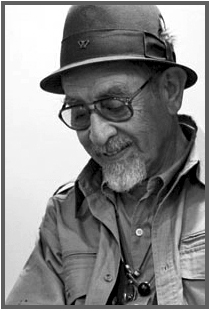

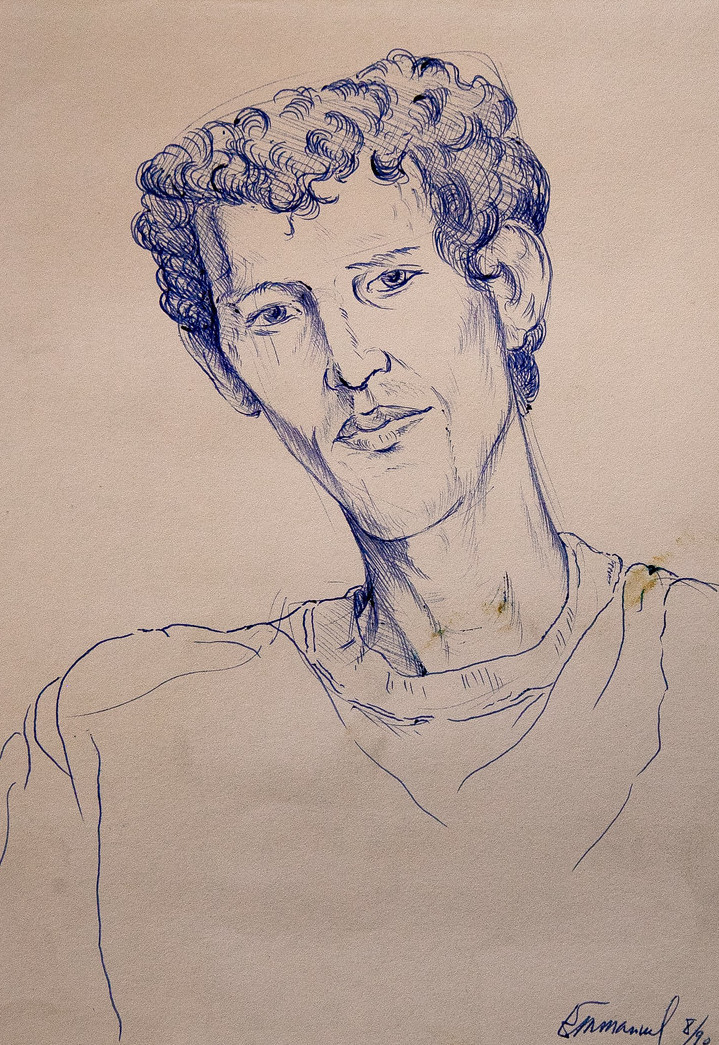

Miranda Bergman made this drawing of Montoya.

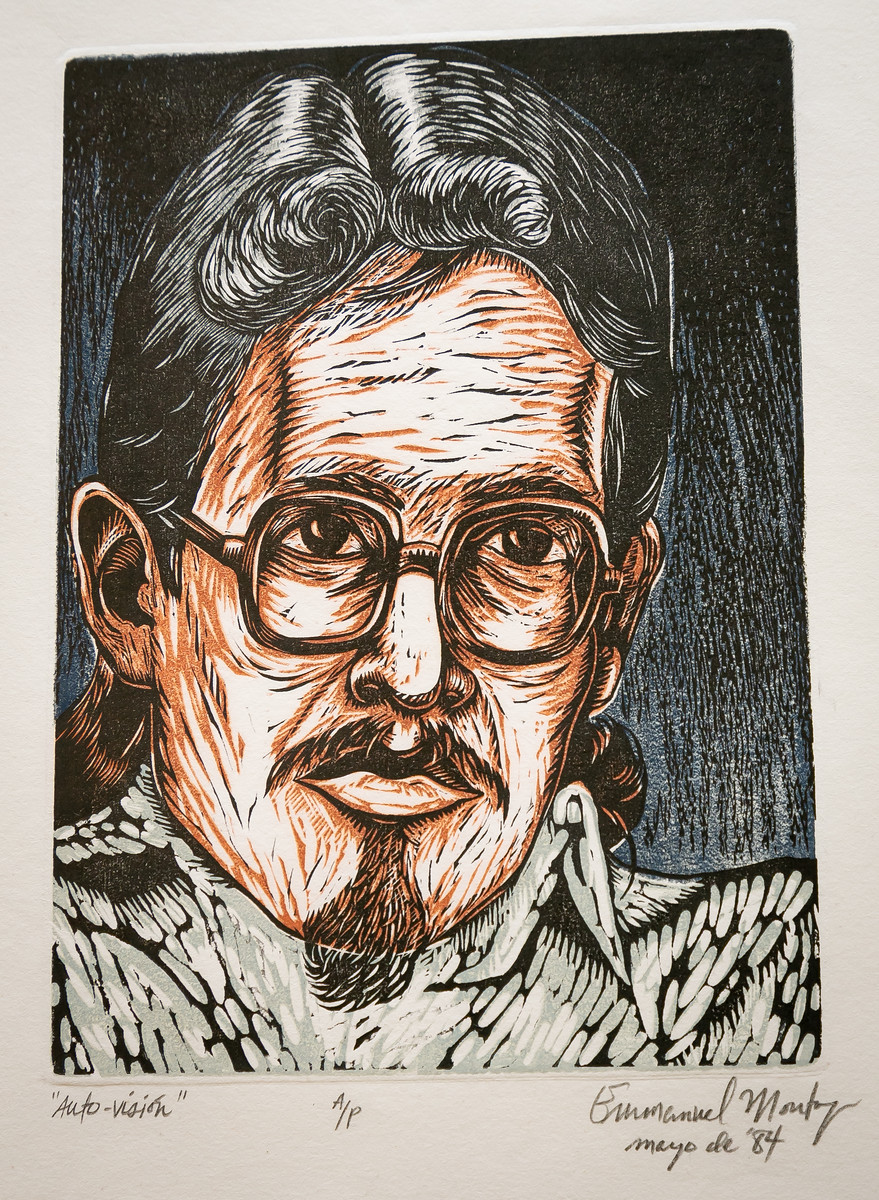

Montoya made this while at SF State.

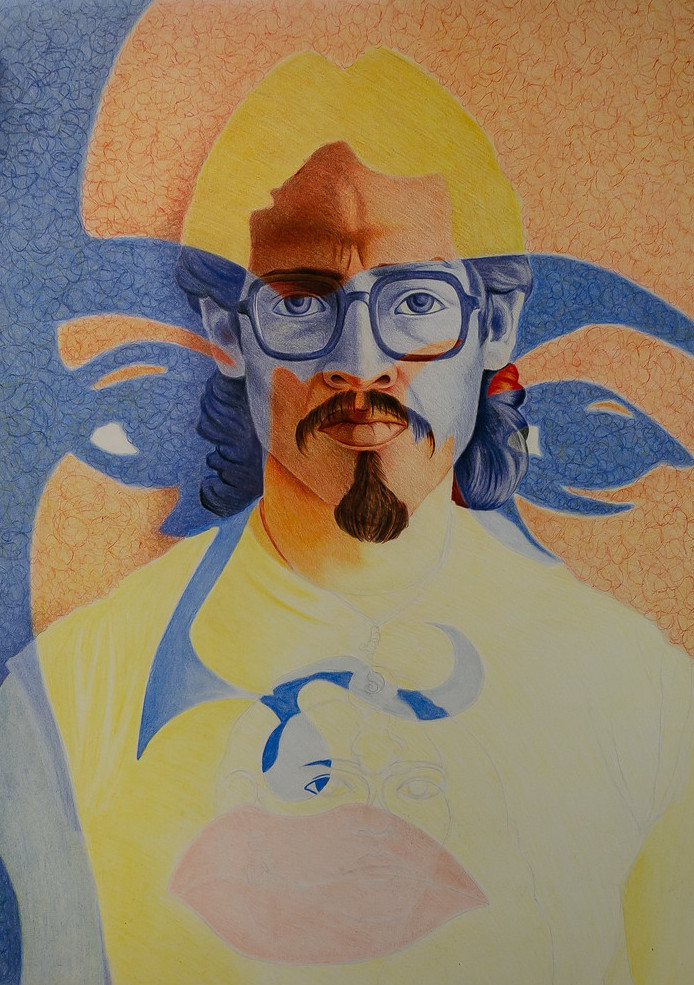

Montoya started but did not finish this self-portrait in 1983. He is wearing a Freida Kahlo t-shirt.

In 1985, Montoya married muralist Juana Alicia. They moved to Berkeley in 1995.

In 1987 and 1988 Montoya studied at San Francisco State’s School of Creative Arts. August Coppola, brother of Francis Ford Coppola, had become Dean of Creative Arts at San Francisco State in 1984.

Coppola identified a room that he was going to dedicate to the Creative Art Student Association – CASA, a pun because the theme was to be Casablanca. Coppola gave Montoya a video tape of Bogart’s Casablanca and off they went – one wall at a time.

The idea was to open it up with mirrors and windows and arches. Mission accomplished – totally cool room.

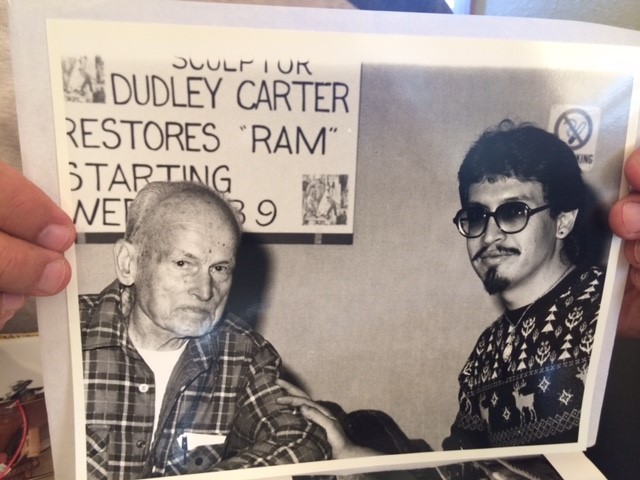

Another very cool project was restoration of a ram sculpture made by Dudley Carter in the 1940s on Treasure Island at a time when Diego Rivera was in San Francisco.

Rivera painted Carter carving the ram in a mural.

The sculpture had laid on the grounds at the San Francisco City College for 40+ years, the victim of the elements and vandals and school spirit (it had been painted the school colors).

Montoya was in the middle of the restoration project and part of the effort to bring Carter into the effort.

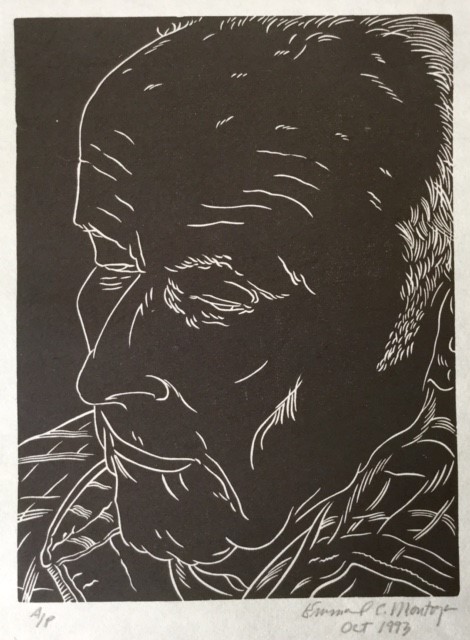

Montoya made this linocut of Carter.

The ram is safe and sound inside now. This article gives a good account of the making and restoration of the ram.

Montoya won a residency at the Kala Art Institute on Heinz Street in 1993.

Kala describe its mission as “to help artists sustain their creative work over time through its Artist-in-Residence and Fellowship Programs, and to engage the community through exhibitions, public programs, and education.” It was started in 1974 by Archana Horsting and Yuzo Nakano. It is nurturing, prodding, and supportive. He is still part of it and uses its facilities. And he has made art consistently and greatly.

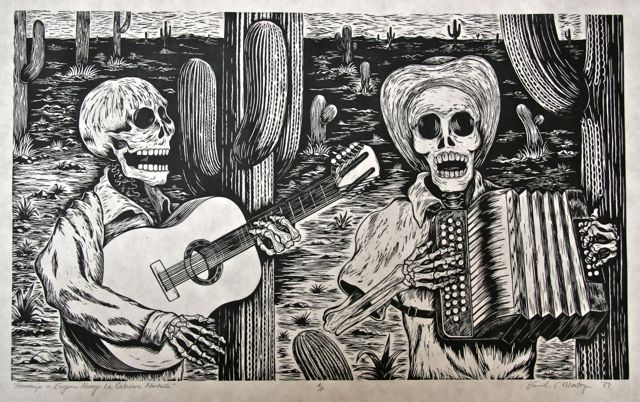

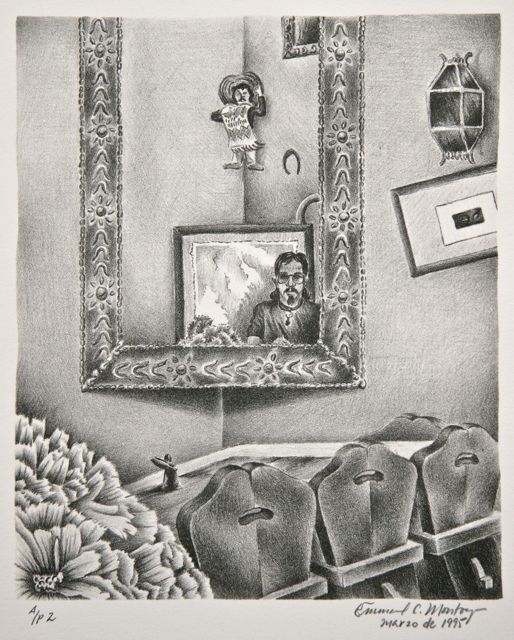

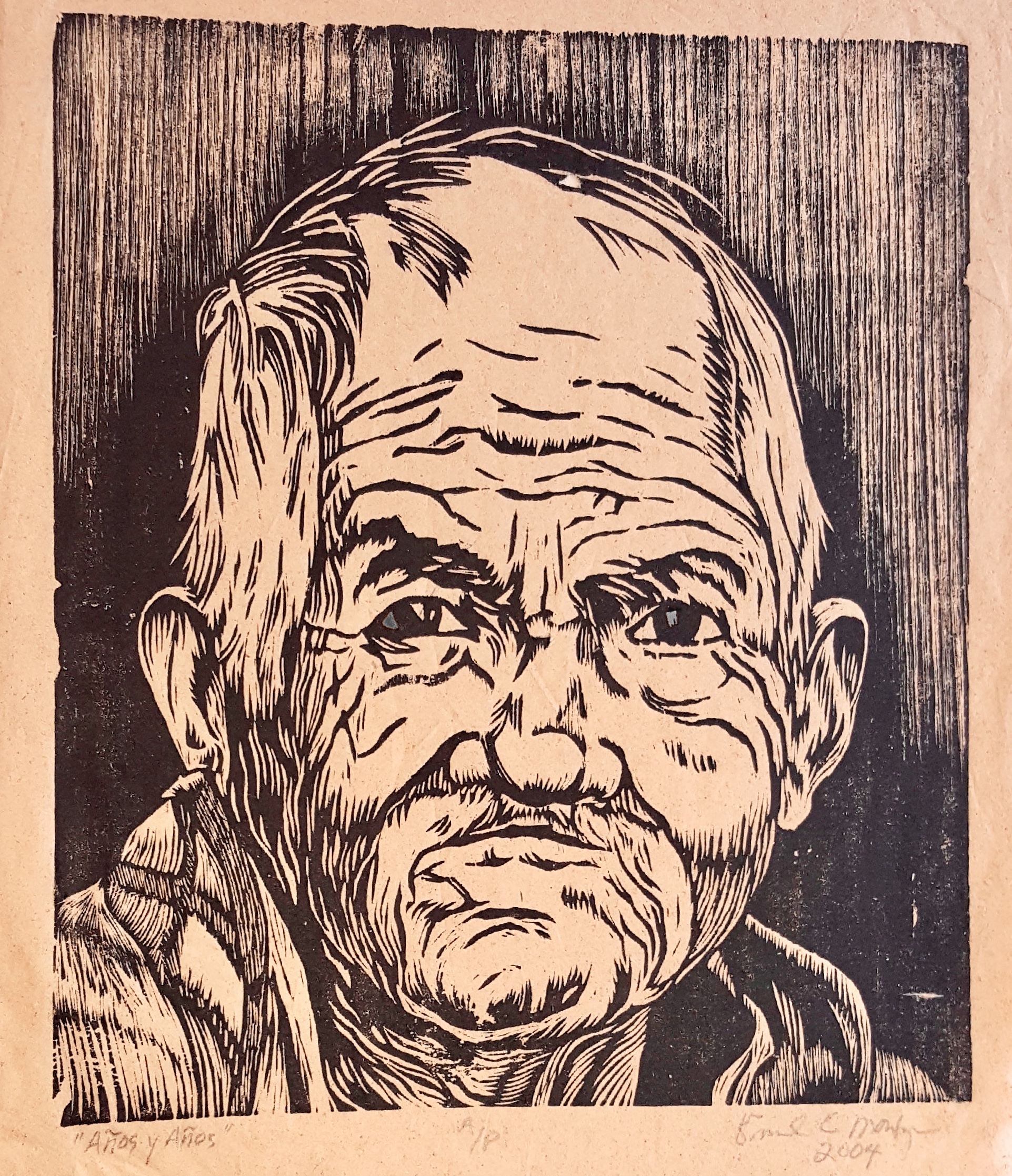

Here is some of Montoya’s graphic work. Most of his prints are made with linocut, a printmaking technique that is a variant of woodcut in which a sheet of linoleum is used for a relief surface. A design is cut into the linoleum surface with a sharp knife, V-shaped chisel or gouge, with the raised (uncarved) areas representing a reversal (mirror image) of the parts to show printed. The linoleum sheet is inked with a roller (called a brayer), and then impressed onto paper or fabric. The actual printing can be done by hand or with a printing press.

This is Homage to José Montoya, of the Royal Chicano Air Force. Montoya (May 28, 1932 – September 25, 2013) was a poet and an artist from Sacramento, California. He was an influential Chicano bilingual poets and Sacramento’s poet laureate.

The Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF) is a Sacramento-based art collective founded in 1970 by José Montoya and Esteban Villa that became one of the most important collective artist groups in the Chicano art movement in California during the 1970s and the 1980s.

Montoya used a Prismacolor color pencil to colorize the print. These are details of colorized version.

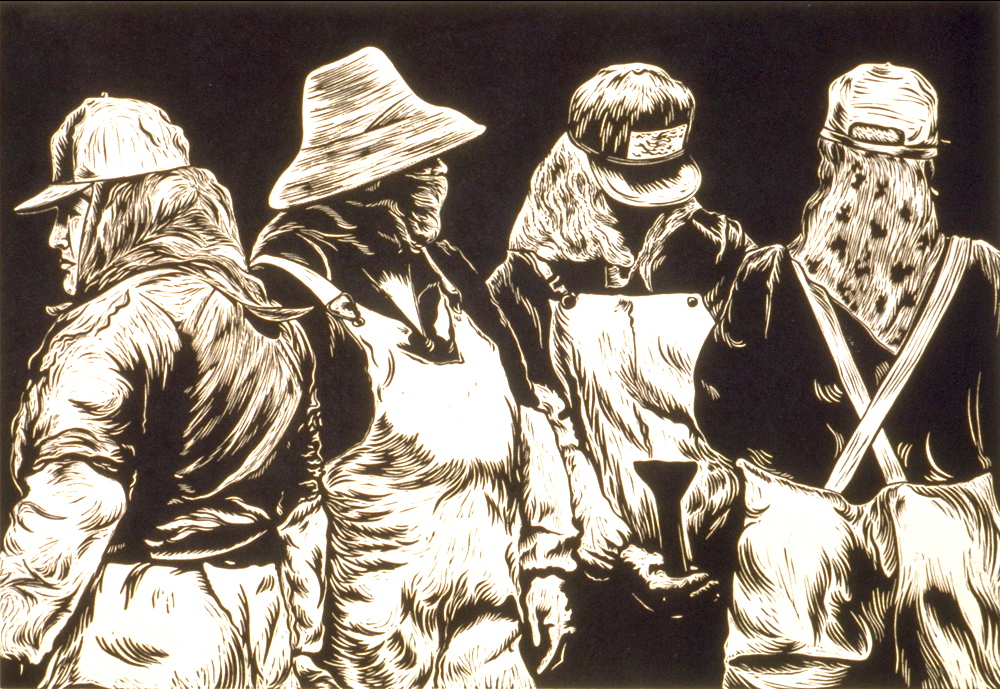

This negative print is of inmates with whom Montoya worked.

Another negative print of “Catarino.”

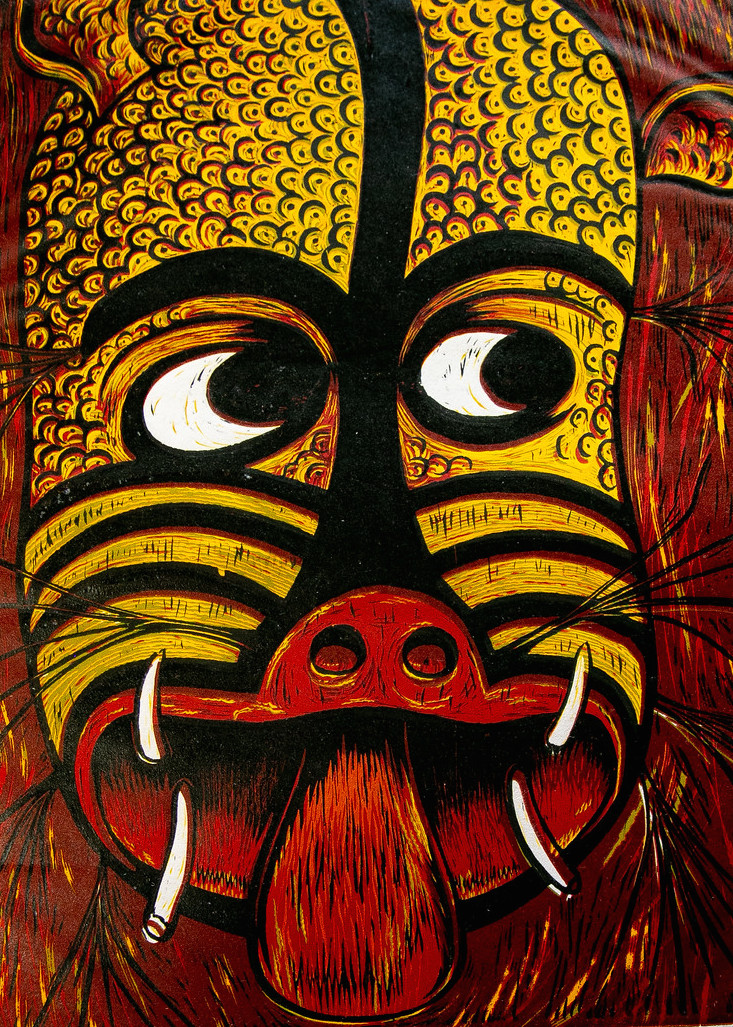

“El Tigre” (the jaguar) started as a black and white print.

And then came color.

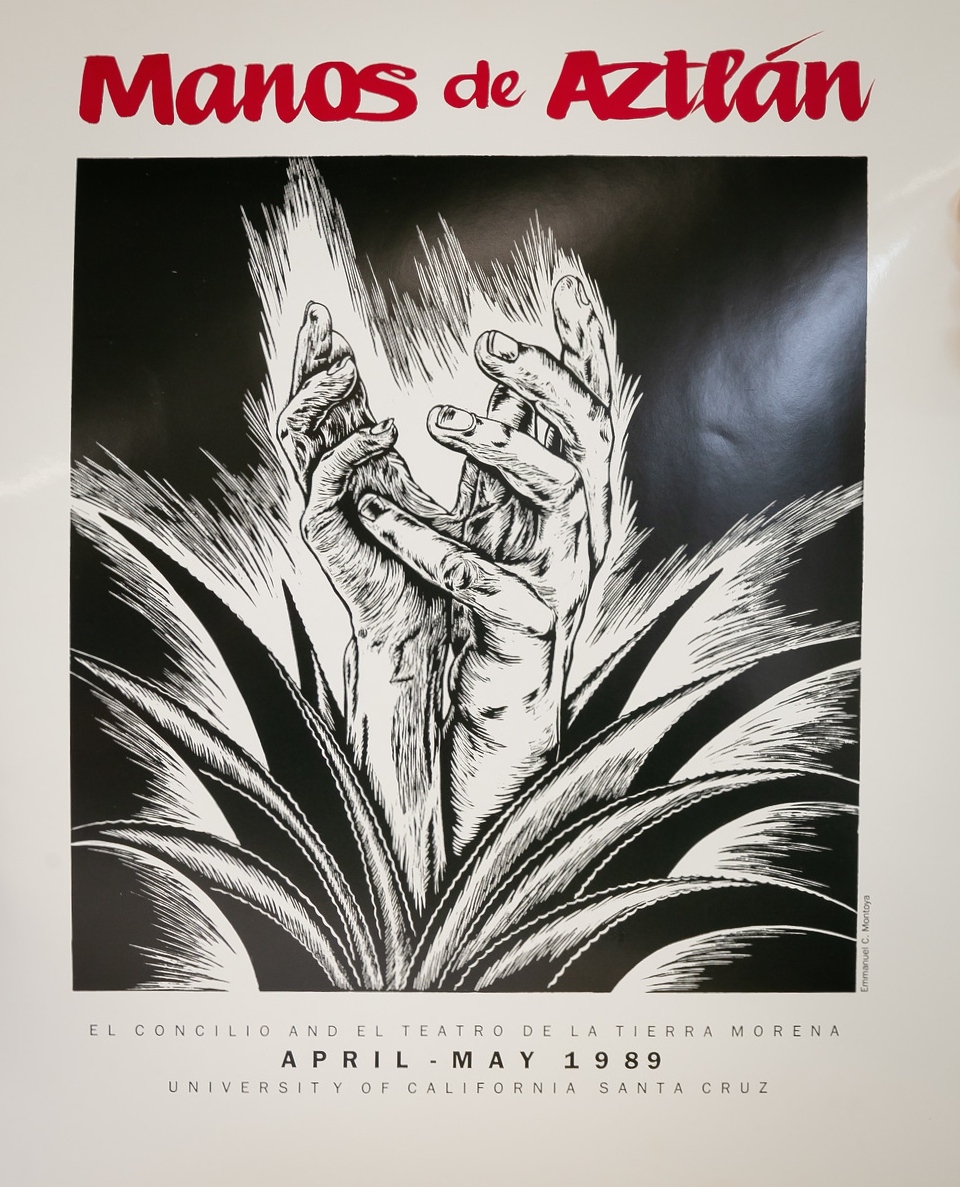

Aztlán (from Nahuatl languages: Aztlān) is the ancestral home of the Aztec peoples. Historians have speculated about the possible location of Aztlan and tend to place it either in northwestern Mexico or the southwest US, although there are doubts about whether the place is purely mythical or represents a historical reality.

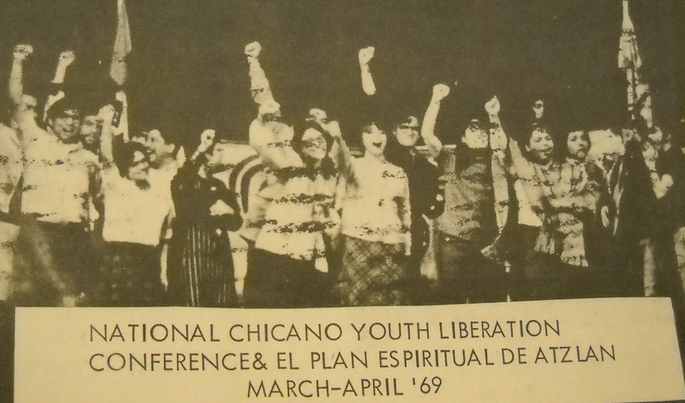

In 1969 the notion of Aztlan was introduced by the poet Alurista (Aberto Baltazar Urista Heredia) at the National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference held in Denver, Colorado by the Crusade for Justice, hosted by Rodolfo Gonzales There Alurista read a poem, which has come to be known as the preamble to El Plan de Aztlan or as “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan” due to its poetic aesthetic.

For Chicanas and Chicanos, Aztlan refers to the Mexican territories annexed by the United States as a result of the Mexican–American War of 1846-1848.

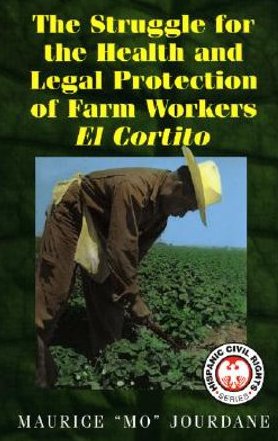

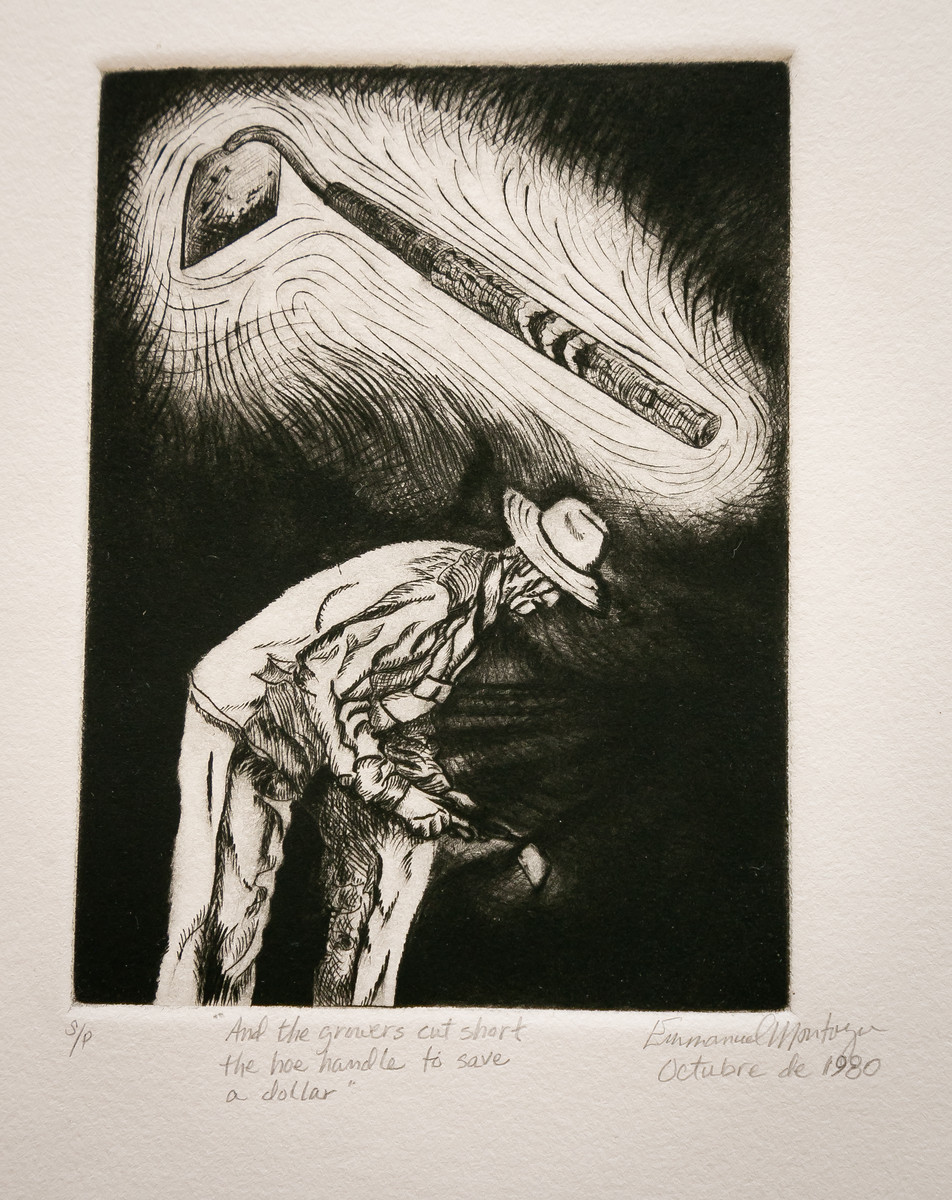

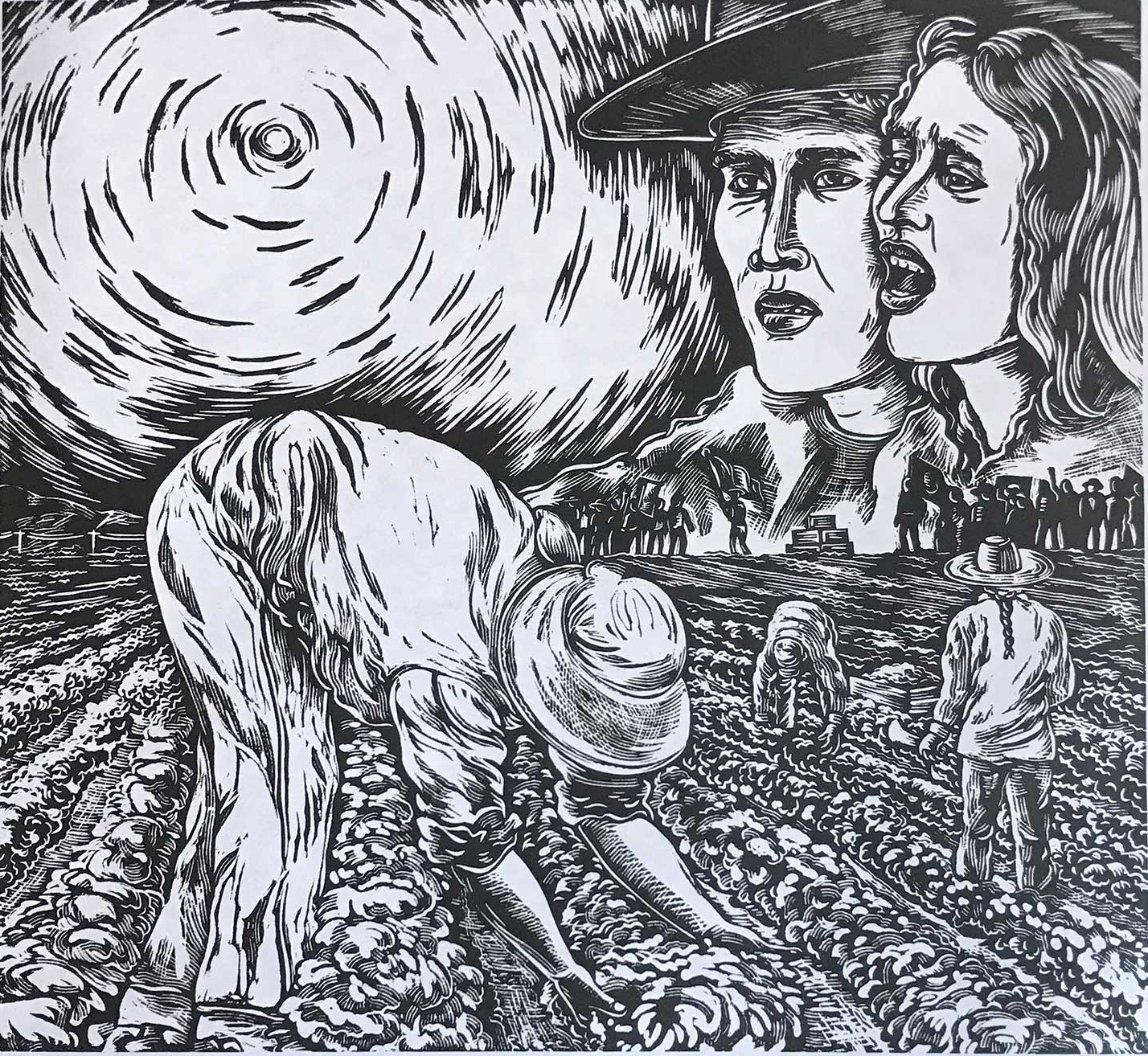

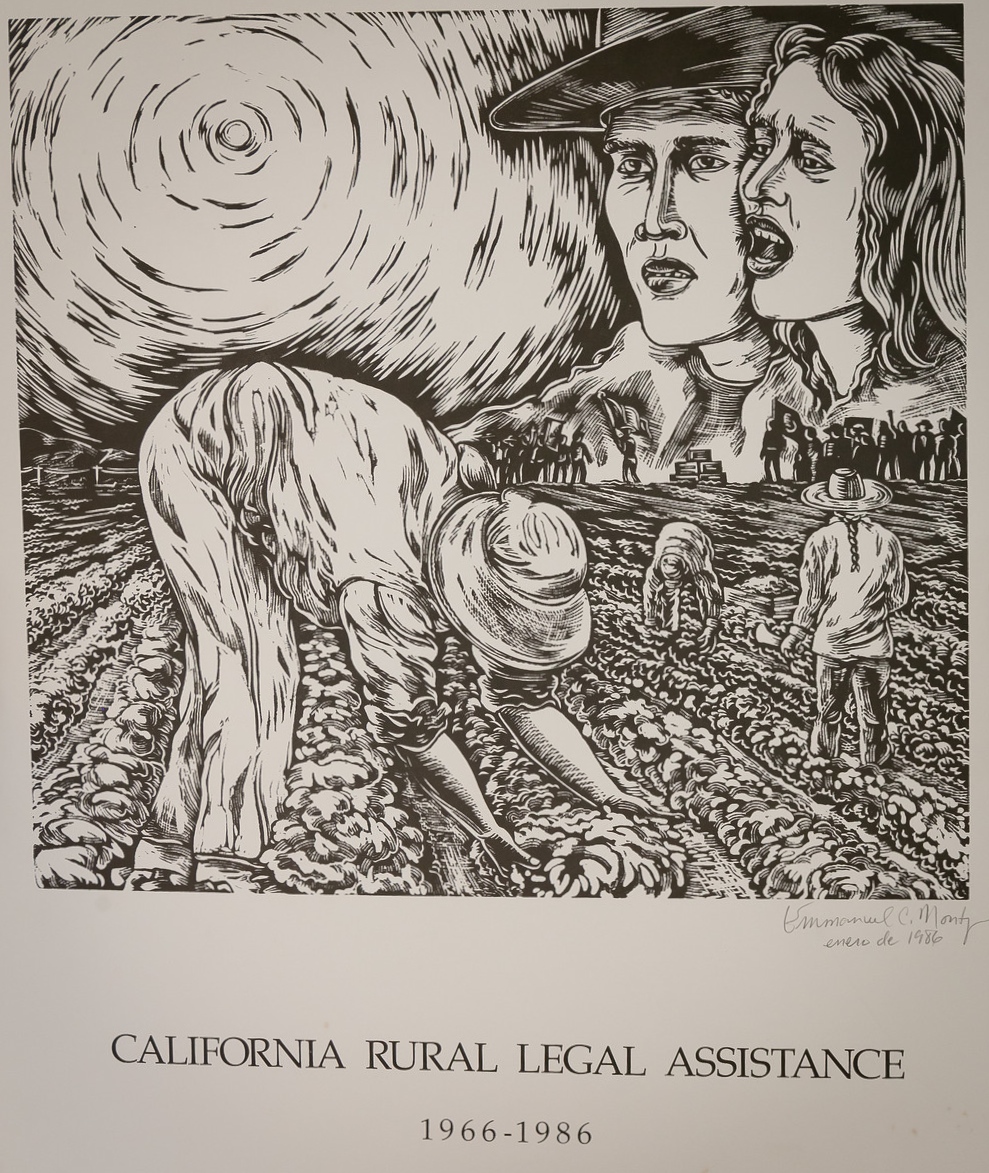

The short-handled hoe (el cortito) embodied oppression of farm workers.

The short-handled hoe (el cortito) embodied oppression of farm workers.

It was outlawed on health and welfare reasons in California in the 1970s as a result of litigation brought by California Rural Legal Assistance attorney Mo Jourdane.

It was outlawed on health and welfare reasons in California in the 1970s as a result of litigation brought by California Rural Legal Assistance attorney Mo Jourdane.

Montoya envisions this piece blown up to the size of a billboard. That would be really something. This piece hits home with me and evokes all that I knew and felt about farm workers when with the UFW.

As does this print of lechugueros (lettuce cutters). his print was used in a poster.

In my UFW years we knew, respected, and worked with CRLA.

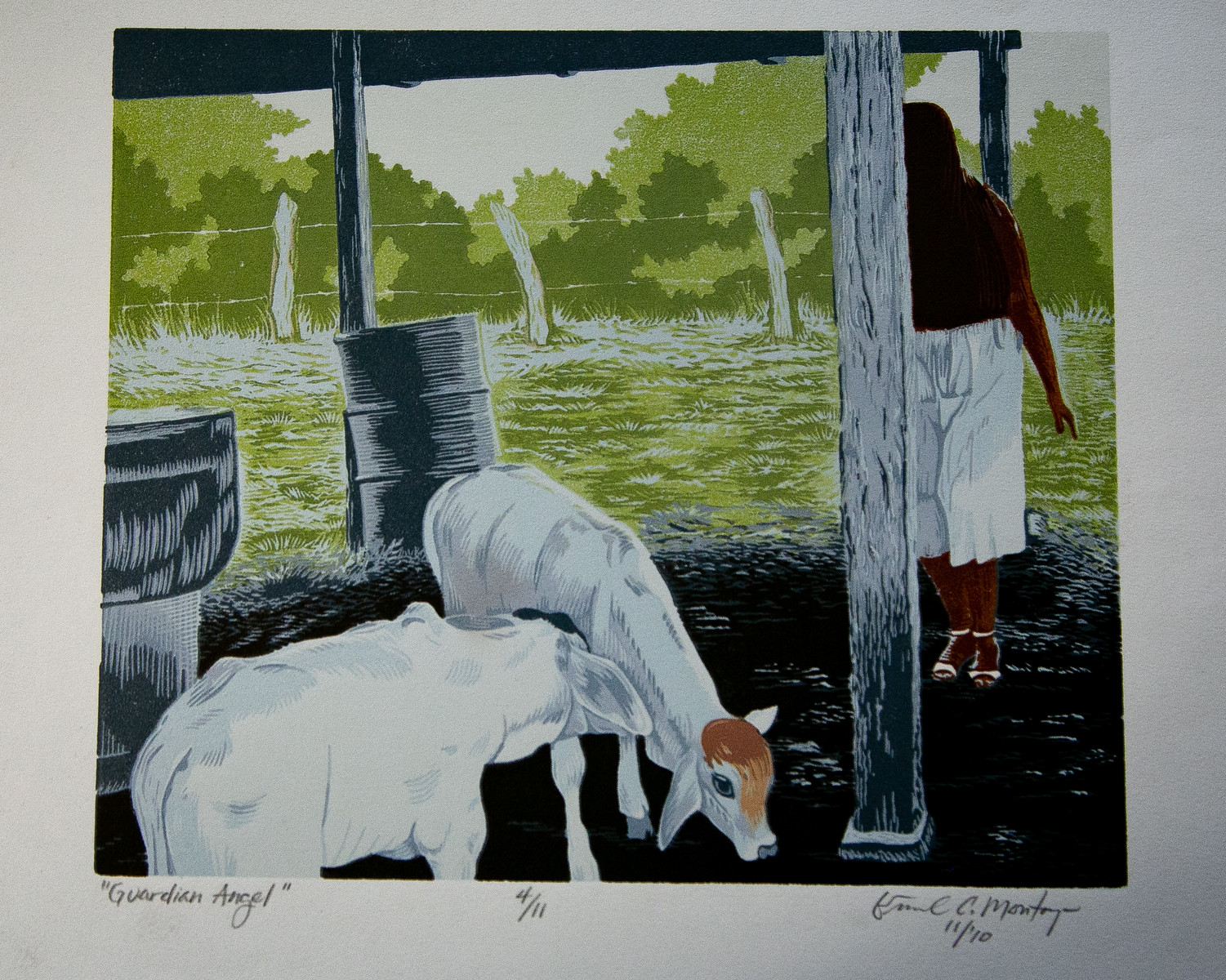

You say Texas and I say boots, farm worker or not. These boots were made by a real master. The color is achieved through the “suicide method” of linoleum printing.You print the area you want with the first color, and then carve that space out. You continue until the final color, with almost all the piece’s space not carved out.

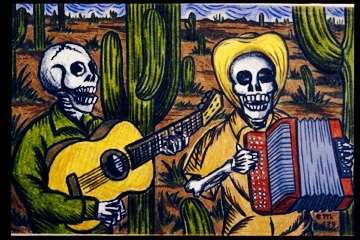

Montoya made this sketch with a Prismacolor pencil on paper in 1979. It was the origin of this Linocut:

Note that several of the cacti are leaning towards the left as if a spirit were moving them.

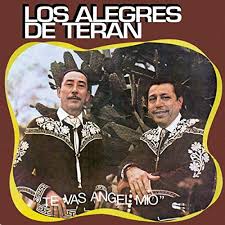

Montoya here celebrates the life of Eugenio Abrega, one of the original members of Los Alegres de Terán, a Norteño music group from Mexico. They were formed in Nuevo León when Eugenio Abrego and Tomas Ortiz met in a club in the mid 1940s. They eventually settled in McAllen Texas, the heart of the Rio Grande Valley.

Beginning with their first record in 1948, “Corrido de Pepito”, Los Alegres de Terán were pioneers of norteño style duets singing corridos, rancheras and norteño songs. The duo is featured in Les Blank’s film Culas Fronteras, the film that had such a significant impact on Montoya.

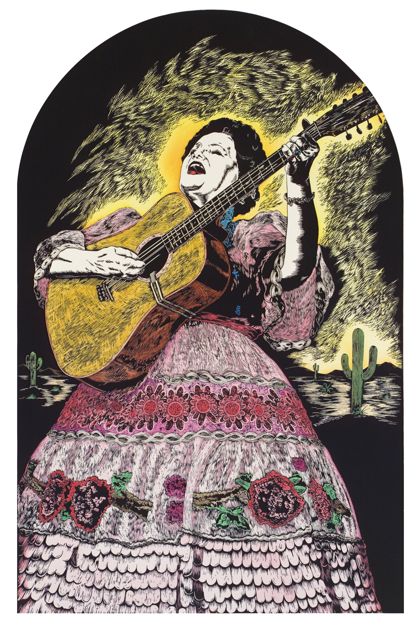

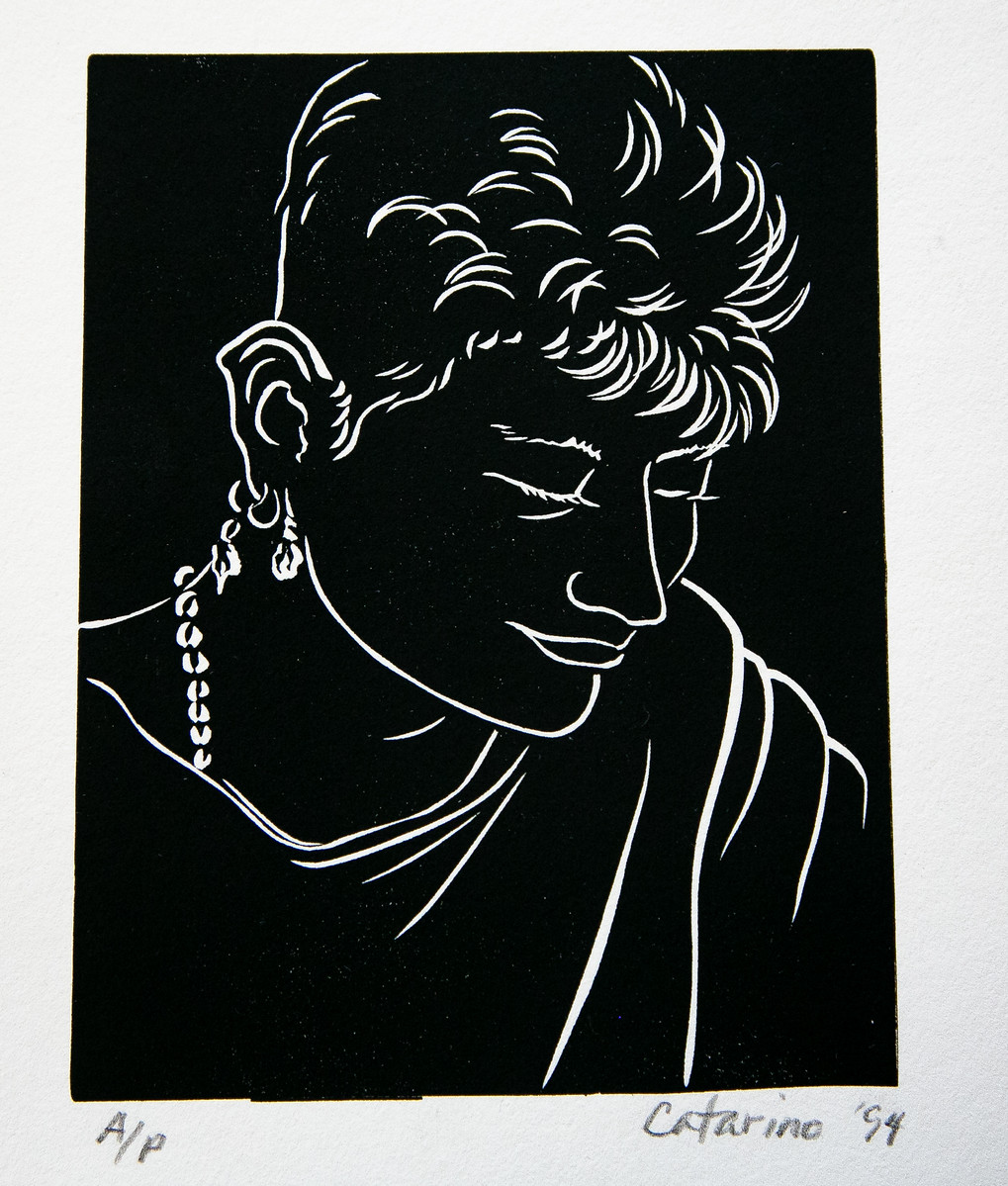

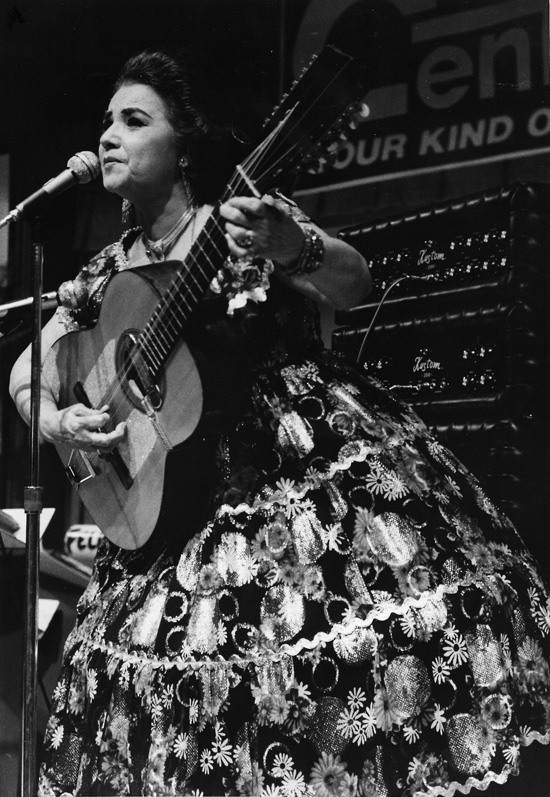

Speaking of legends of the border, Montoya used a photo of Lydia Mendoza to make a linocut print.

And with silk screened color added:

Lydia Mendoza (1916-2007) was a Texan twelver-string guitar player and singer of Tejano, conjunto, and traditional Mexican-American music. She is known as La Alondra de la Frontera” (“The Lark of the Border”). She is a cardinal figure in Tejano, Tex-Mex, and Mexican-American culture. Stanford bought one of the Montoya’s prints of her; they have a Lydia Mendoza homemade dress in their collection.

Lydia Mendoza (1916-2007) was a Texan twelver-string guitar player and singer of Tejano, conjunto, and traditional Mexican-American music. She is known as La Alondra de la Frontera” (“The Lark of the Border”). She is a cardinal figure in Tejano, Tex-Mex, and Mexican-American culture. Stanford bought one of the Montoya’s prints of her; they have a Lydia Mendoza homemade dress in their collection.

Montoya had a sense that Mendoza was not destined to play alone.

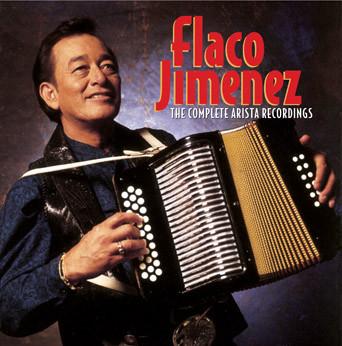

He is now working on a companion for her, Flaco Jimenez.

Leonardo “Flaco” Jiménez (born March 11, 1939) is a Norteño, Tex Mex and Tejano music accordionist and singer from San Antonio, JIménez began performing at the age of seven with his father, Santiago Jiménez Sr, who was a pioneer of conjunto music, and began recording at age fifteen as a member of Los Caminantes. He played in the San Antonio area for several years and then began working with Doug Sahm in the 1960s. He has spanned the music world, playing with established and famous rock bands, experimental cross-over bands like the Free Mexican Air Force, and his own Tex-Mex combo.

Montoya’s Flaco piece is in its infancy. On a second visit, Montoya was adding a roadrunner to the foreground. I very much look forward to his arrival as a companion for Lydia.

And then there is La Trinidad Nortena from 1989.

In the left panel, you see the accordion resting, waiting to be played. In the right panel, a guitar waits. With all three, you see Montoya reaching beyond the rectangular constraints of most prints.

Staying in the music vein, this linocut is of Esteban Jordan (February 23, 1939 – August 13, 2010). a jazz, rock, blues, conjunto and Tejano musician. He was also known as “El Parche” (“The Patch”, because he wore an eye patch), “The Jimi Hendrix of the accordion”, and “the accordion wizard”. An accomplished musician, he played 35 different instruments. Joel Guzman, an acclaimed traditional accordionist from Austin, Texas, said: “”He’s playing flat 5s and raised 11ths, and rhythmically he’s so deep,” “From a musical standpoint, he’s a genius.”

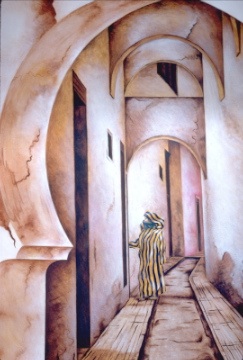

Montoya made these drawings in 2016, based on photos that he took in Morelia, Michoacan. He calls them El Nuevo Tenochtitlan. Tenochtitlan was a large city-state in what is now the center of Mexico City. The most commonly accepted date of its founding is March 13, 1325. The city was built on an island in what was then Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico. The city was the capital of the expanding Aztec Empire in the 15th century until it was captured by the Spanish in 1521.

This self-portrait is from the same time period.

Homenaje at Leopoldo Mendez Contra la Benedicion del Poder Nuclear. Photo courtesy of Emmanuel Montoya.

A powerful warning about nuclear power.

This is a traditional woodcut. Like a linocut, it uses a relief process – what is not cut away is what is printed.

Another hand-colored linocut.

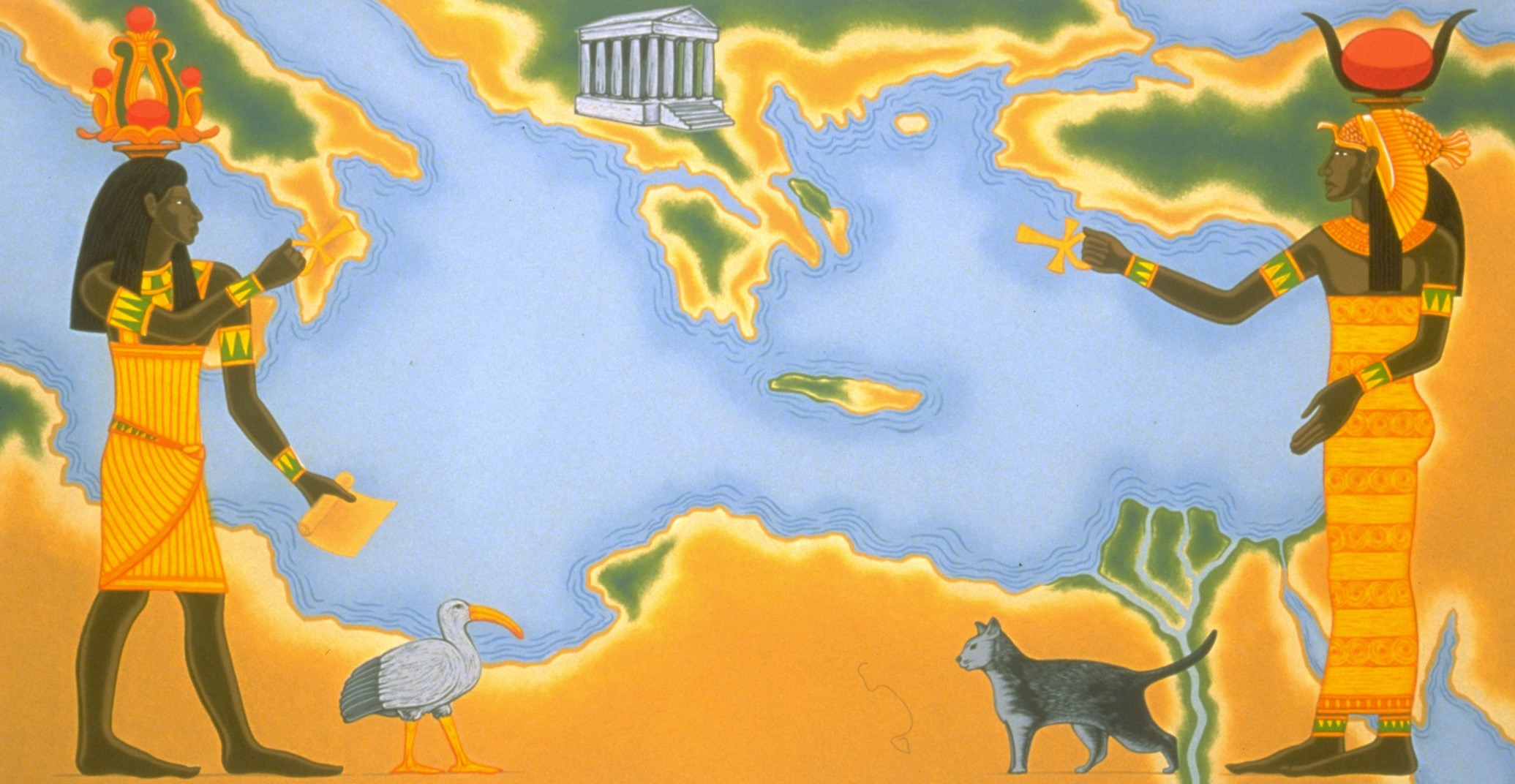

This was the first piece of Montoya’s that I saw and I remains a favorite. Note the pre-Columbian images in the blue background.

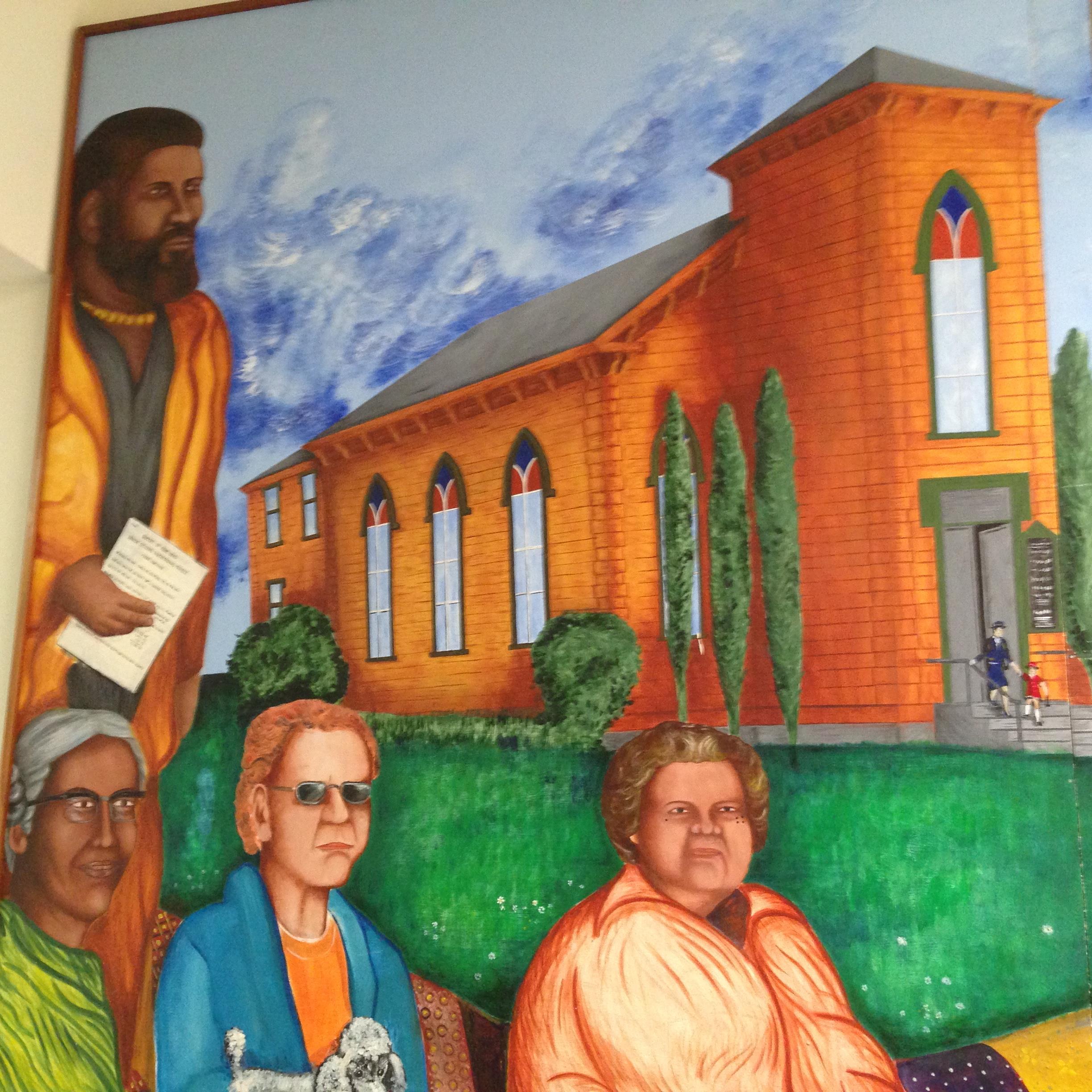

Montoya has worked with murals as well as linocuts. The murals shown below display his creativity and craft as a muralist.

This 1978 mural in the Fair Oaks Community Center in Redwood City is called “Hour for Senior Power” and it celebrates seniors. The style is evocative of North American muralists of the 1930s and 1940s.

I don’t know about you, but these murals rock me to my gypsy soul as Van Morrison would say.

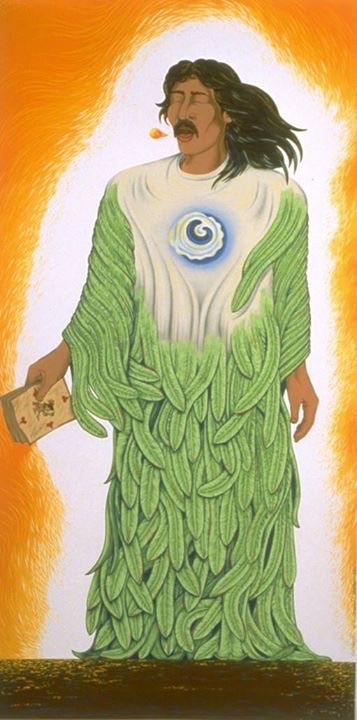

Between 1993 and 1999, Montoya had a commission from the San Francisco Arts Commission for three paintings which are now permanent installations at the Mission Branch, San Francisco Library.

Montoya worked on this first piece for several years.

Quetzalcoatl (“feathered serpent” or “plumed serpent”) is the Nahuatl name for the Feathered-Serpent deity of ancient Mesoamerican culture. Montoya used the suicide method of linoleum printing with between 35 and 40 colors.

And the third:

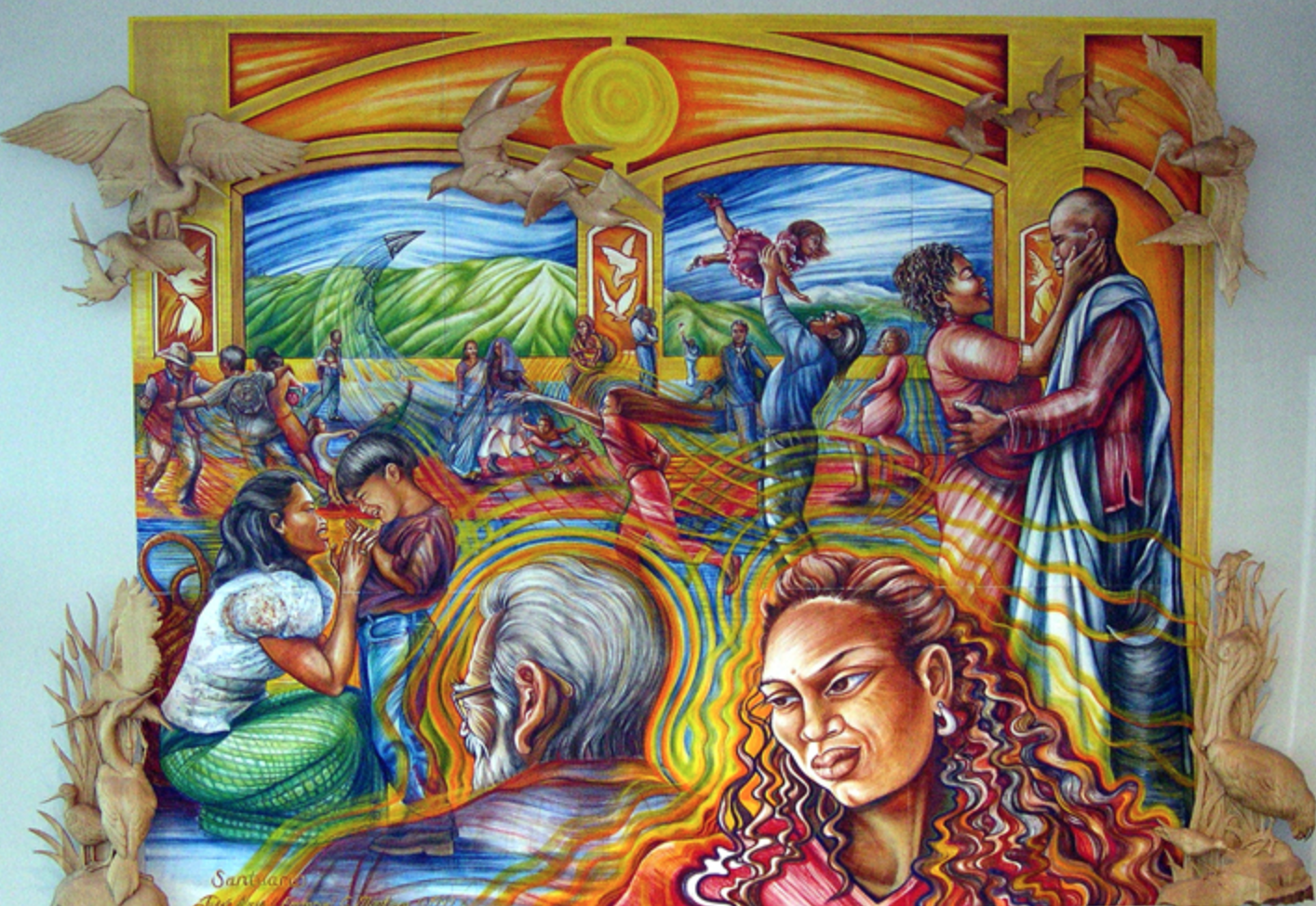

In 1999, Montoya and Juana Alicia collaborated on Santuario/Sanctuary at the San Francisco Airport, International Terminal G, Gate 99

Juana Alicia painted the mural.

Montoya sculpted the birds. He was a self-taught woodworker.

Below, Montoya holds a sketch of a mural never painted.

It was a project sponsored by the Rain Forest Action Network, showing the rain forest as the lungs of the earth. On the left is Francisco Alves “Chico” Mendes Filho, better known Chico Mendes (December 15, 1944 – December 22, 1988), a Brazilian rubber tapper, trade union leader and environmentalist who fought to preserve the Amazon rainforest, and advocated for the human rights of Brazilian peasants and indigenous peoples. He was assassinated by a rancher on December 22, 1988.

The mural was designed for an old firehouse in the Western Addition, but the permission of the Bank of America was needed but not obtained.

Montoya visited Nicaragua in 1990 and made these;

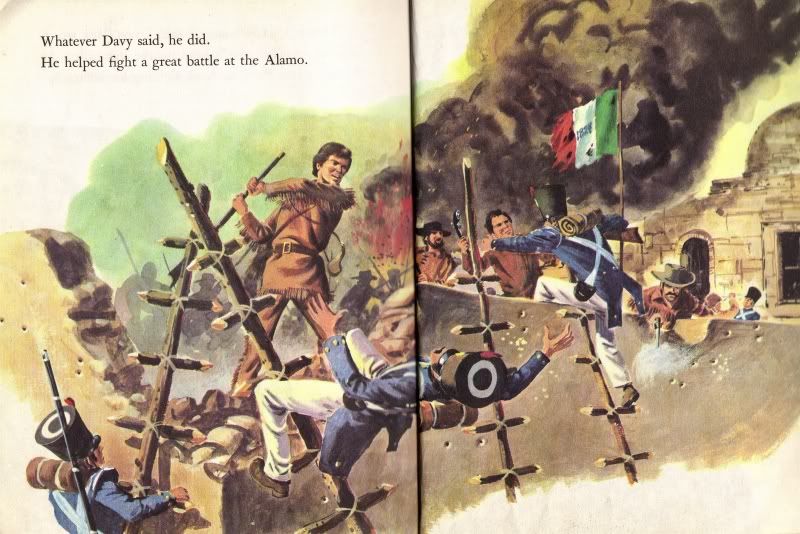

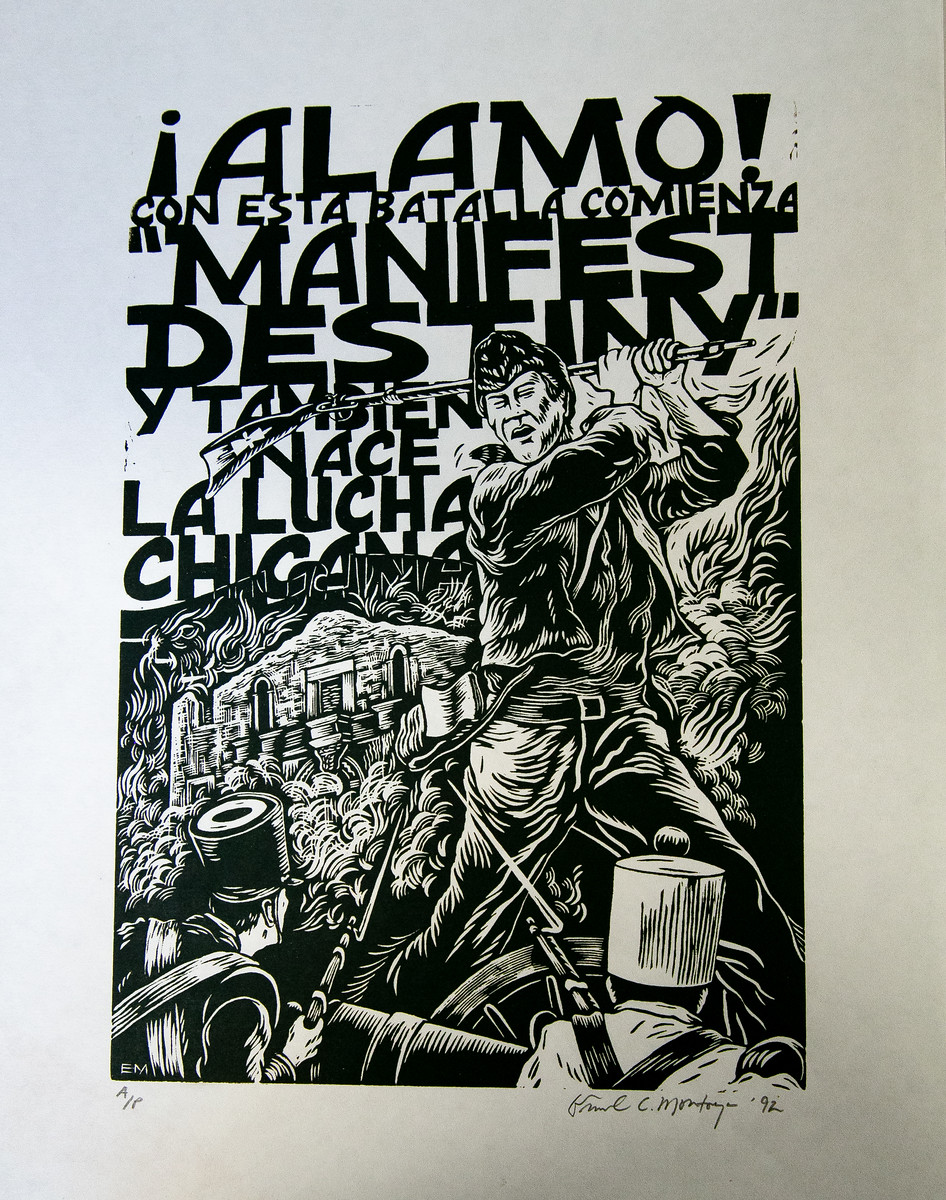

Over the years, Montoya has made several pieces depicting the Alamo is a glorification of American hegemony.

In December 1835, during Texas’ war for independence from Mexico, a group of Texan volunteer soldiers occupied the Alamo, a former Franciscan mission located near the present-day city of San Antonio. On February 23, 1836, a Mexican force numbering in the thousands and led by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna began a siege of the fort. Though vastly outnumbered, the Alamo’s 200 defenders–commanded by James Bowie and William Travis and including Davy Crockett—held out for 13 days before the Mexican forces finally overpowered them.

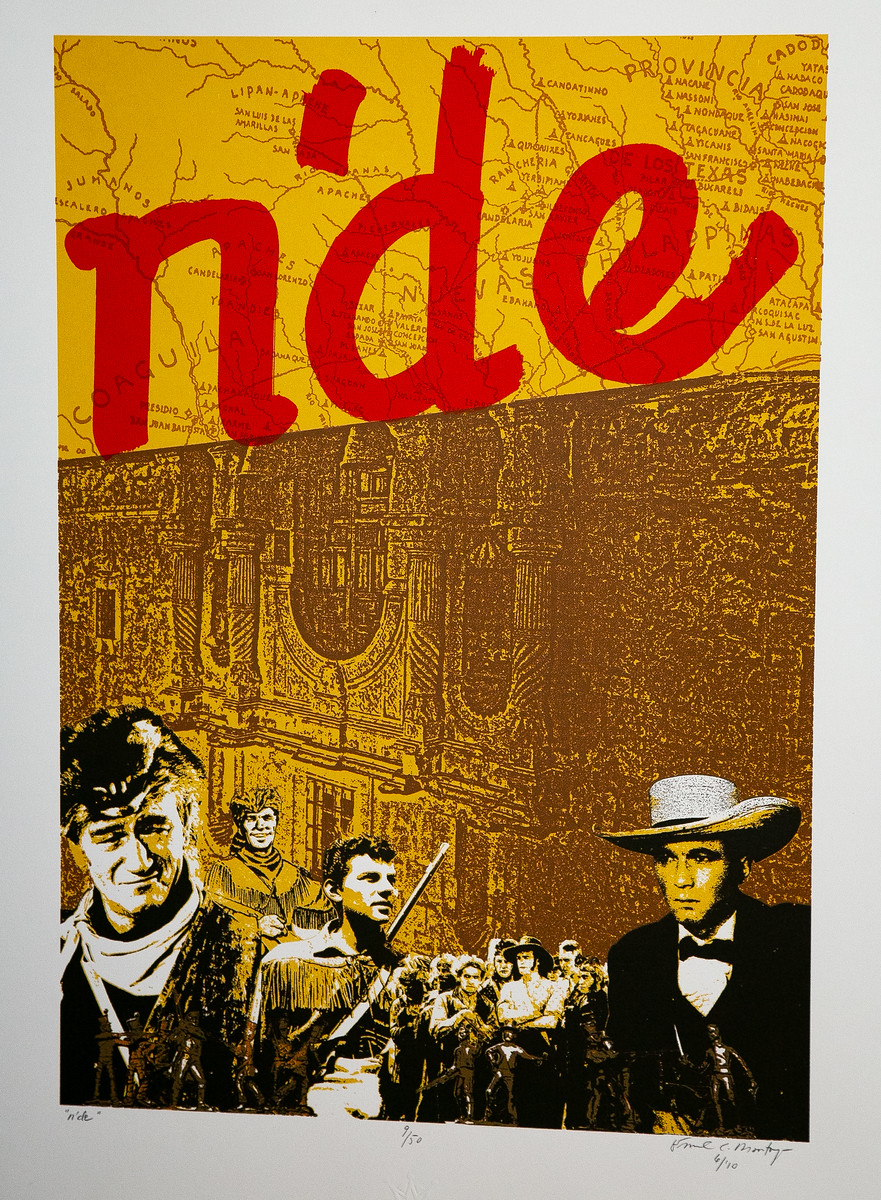

This poster alludes to the 1960 movie The Alamo, starring John Wayne, Frankie Avalon, and Laverne Harvey. “n’de” is from the Apache language.

Manifest Destiny, as every schoolchild knows, is the 19th-century doctrine or belief that the expansion of the United States throughout the American continents was both justified and inevitable.

Of this, Montoya wrote: “In the days before the final assault of Santa Ana’s overwhelming numbers, Colonel Travis wrote numerous letters calling for reinforcements. HELP” Of course, who better to show up than … The Beatles! Look closely and you’ll see the other “Icons”. From left to right: Tennis great,Arthur Ashe followed by Jazz Icon Miles David. To the right of the Mexican flag, the symbolic “end of the trail.” Farther to the right is an image that was heard around the world, the execution of a Vietcong Prisoner.”

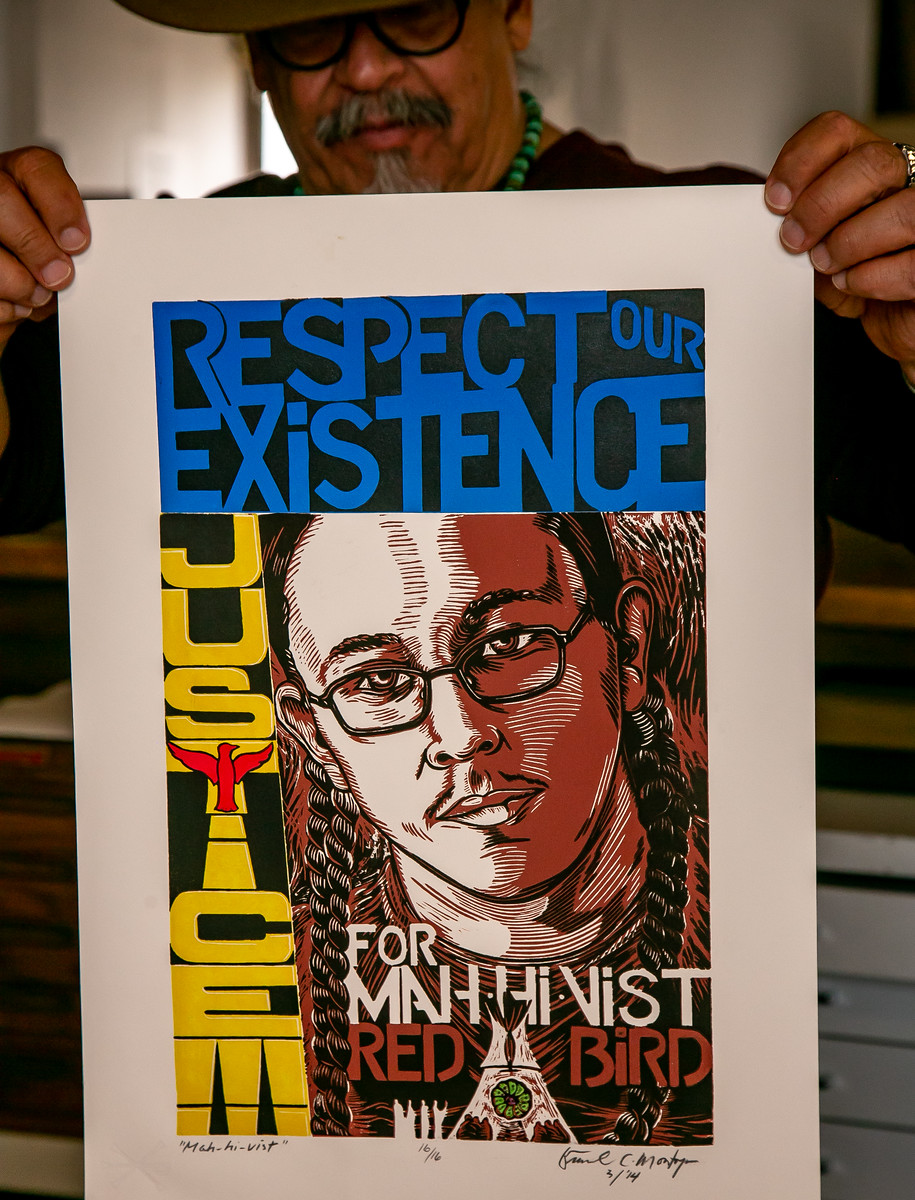

Several works depict martyrs to police or military violence.

Mah-hi-vist (translates in English to “Red Bird”) Touching Cloud Goodblanket was born April 11, 1995 to Wilbur and Melissa (Archer) Goodblanket in Clinton, Oklahoma. He was killed by police on Saturday, December 21, 2013 in his Clinton, Oklahoma, home.

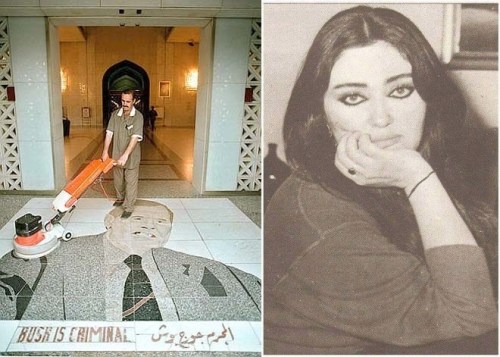

Layla Al-Attar (Arabic: ليلى العطار; May 7, 1944 – June 27, 1993) was an accomplished Iraqi artist and painter who became the Director of the Iraqi National Art Museum. On 27 June 1993, Al-Attar, her husband and their housekeeper were killed by a U.S. missile attack on Iraqi Intelligence main building which was just behind her house, ordered by President Clinton.

Some believe that the strike was not an accident, that it was intended as retribution for an unflattering mosaic of George Bush laid onto the floor at the entrance to the al-Rashid Hotel in Baghdad. The idea was that nobody would be able to get into the hotel, where most foreign visitors to Iraq stayed in the 1990s, without stepping on Bush’s face. The mosaic was removed when Baghdad was captured on 9 April 2003. I personally don’t find that belief convincing.

Montoya had produced a powerful graphic opposing the first US war against Iraq.

The Bay Guardian ran this as a centerfold, which allowed people to use the centerfold a s a poster.

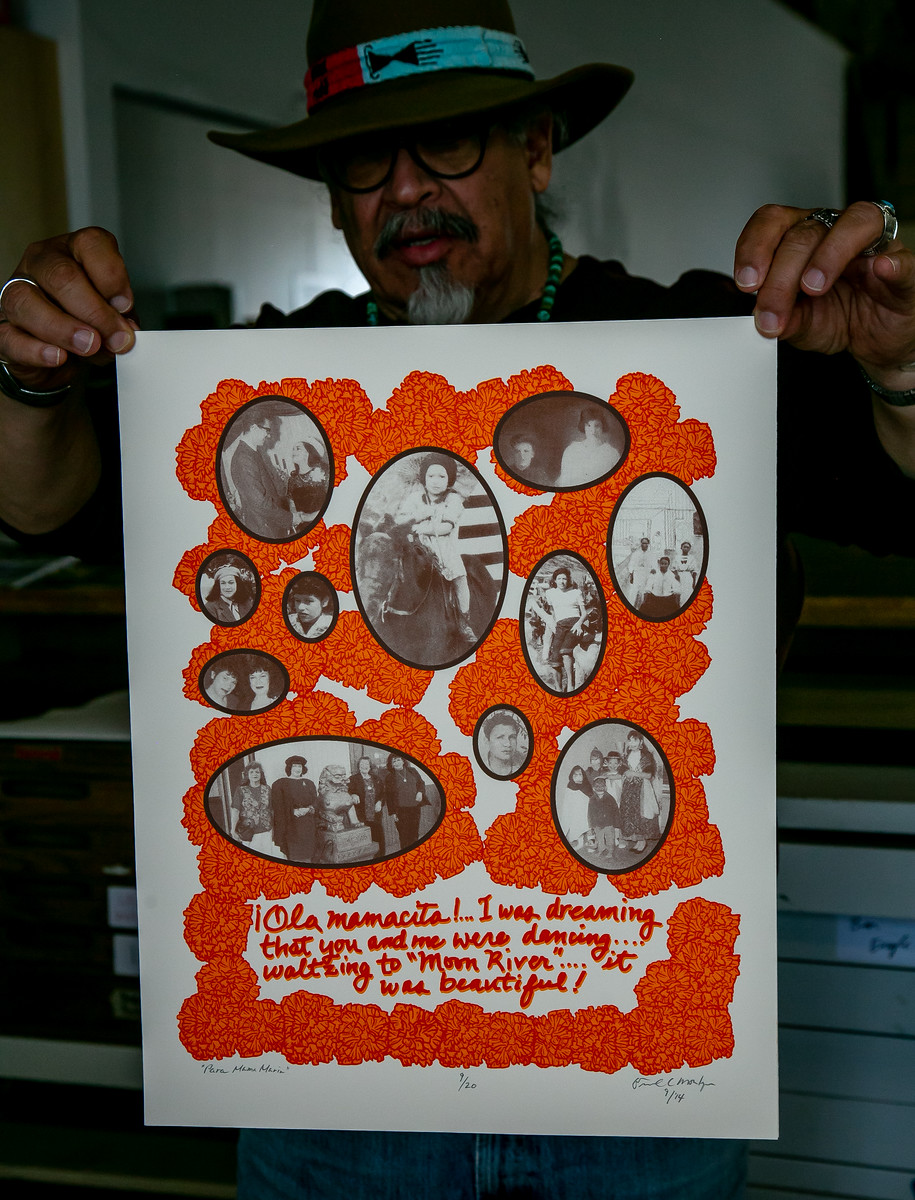

Montoya’s mother died in 2011 in Yankee Hill, an unincorporated community and census-designated place located 6.5 miles east-southeast of Paradise in Butte County, California.

What a kind and loving gesture of art.

What a kind and loving gesture of art.

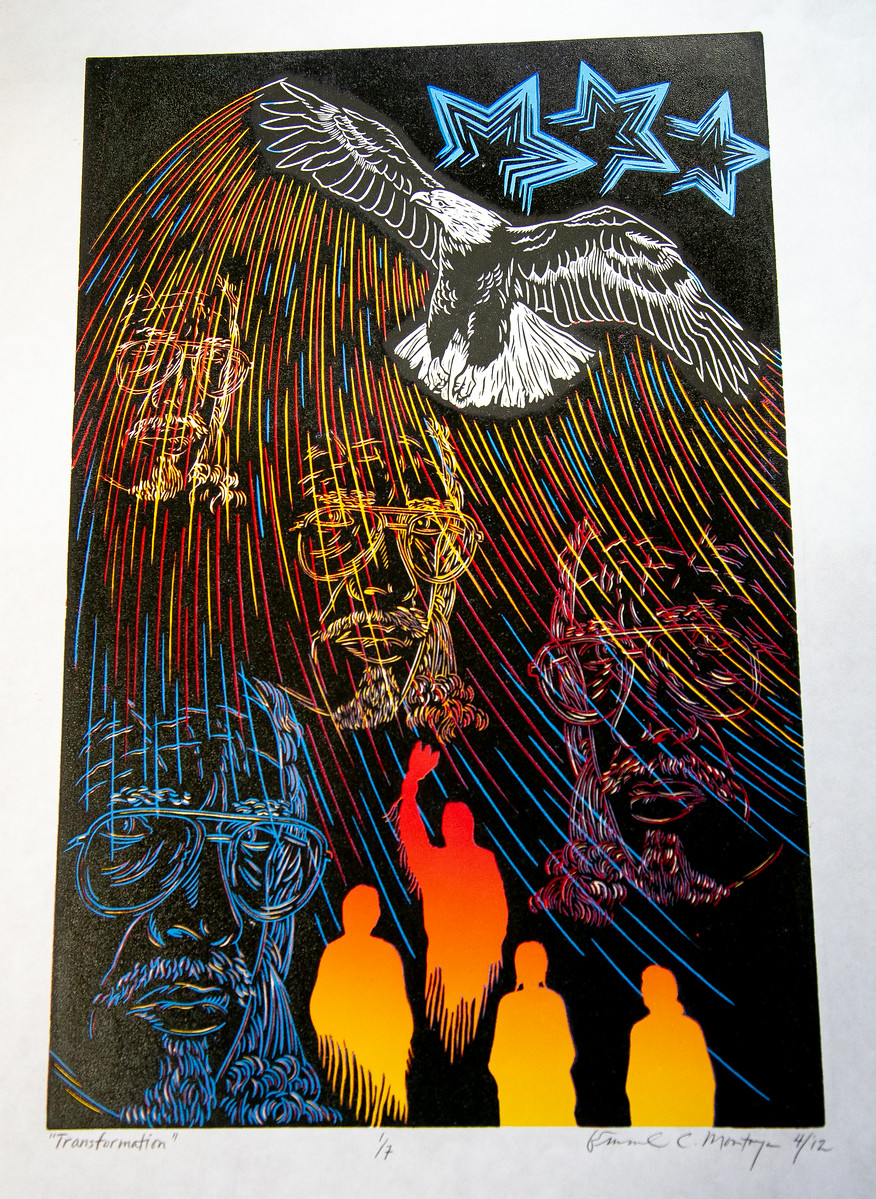

Montoya calls this 2012 piece “Transformation.”

Montoya’s life and work inspire me. He has found and accepted extraordinary mentors and made great art informed by Chicano and Apache culture. I have the sense I haven’t talked to him for the last time.

To see and perhaps buy his art, go to his website (Click on image). If anything is of interest, e-mail Montoya at redbrown60@gmail.com.

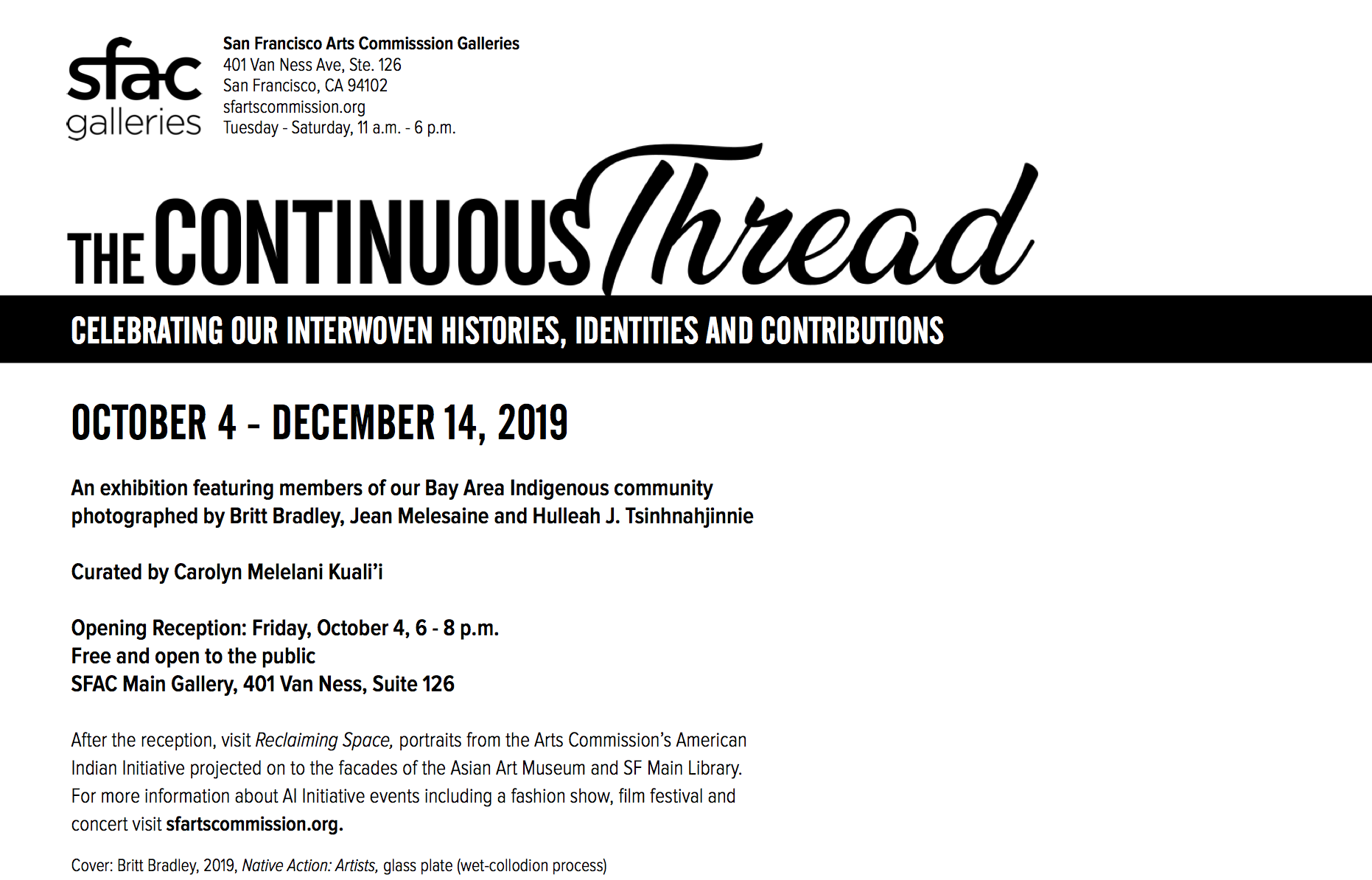

And – a show coming up.

I will be there. As Robert Frost wrote, you come too.

My friend took longer than usual to go through this draft post.

“Amazing. Just amazing. Wanna see what I came across today?”

Whether I did or not I was going to.

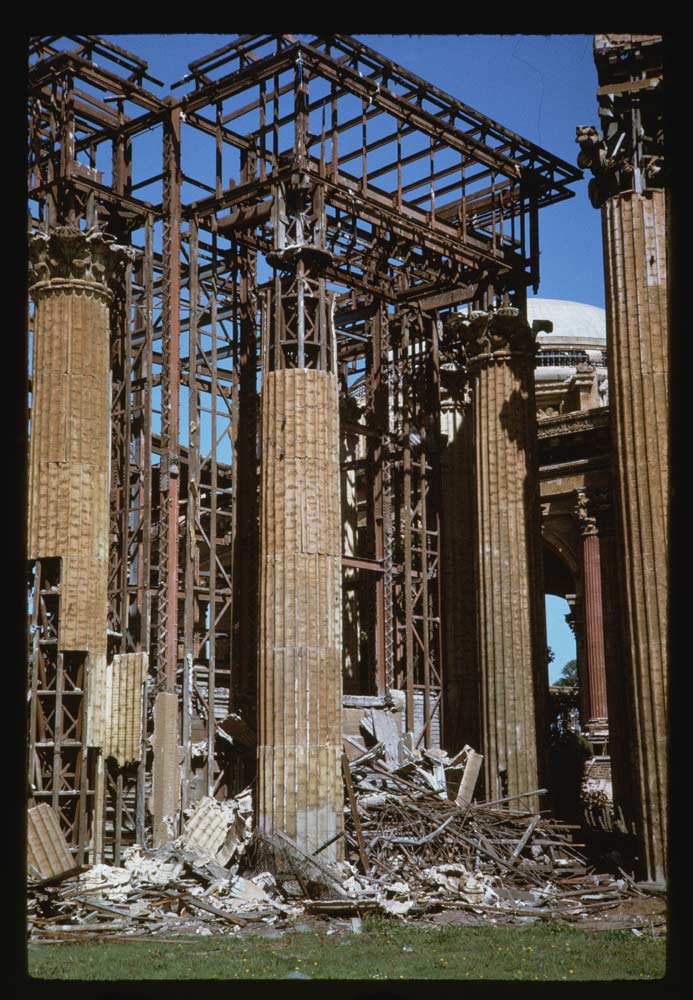

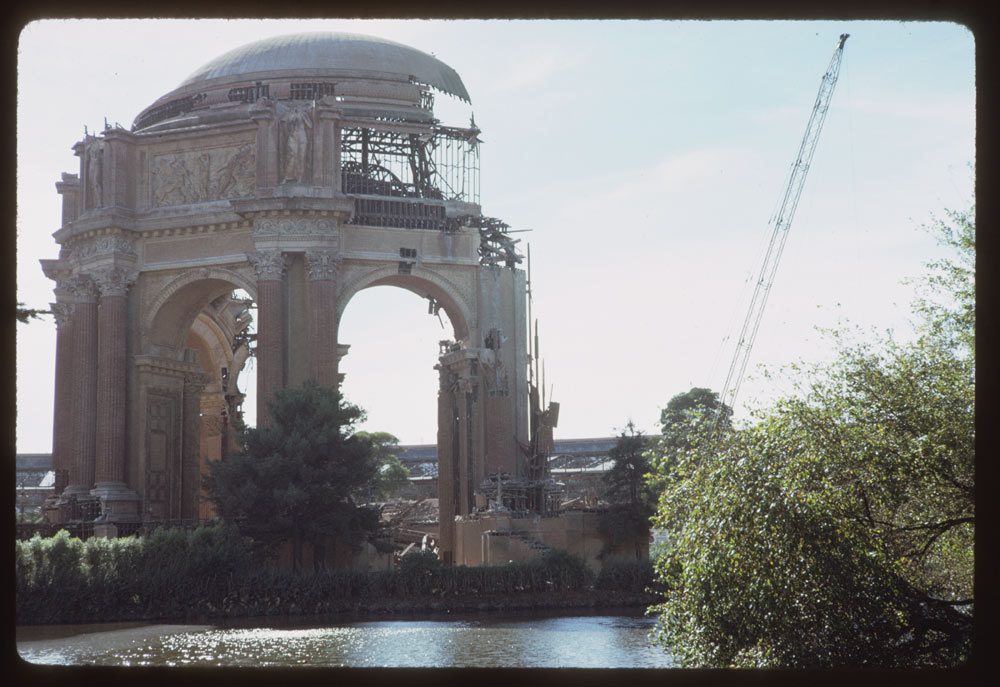

“In 1964 our family took our last family trip ever. We drove from Detroit to San Francisco. Earl had gotten hung up on Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts and wanted to see it. Imagine his surprise when we got here and saw that it was demolished. Only the steel structure of the exhibit hall was left standing. The buildings were then reconstructed in permanent, light-weight, poured-in-place concrete, and steel I-beams were hoisted into place for the dome of the rotunda. All the decorations and sculpture were constructed. The palace that looks ancient and was built in 1915 and then rebuilt in 1964. Not so ancient. ”

I thanked him for his history lesson and asked what he thought of my post about Montoya and his art. He did not hesitate.

Wow Tom! What a superb post! I just loved focusing on each amazing detail and reading

your interesting text. You have just excavated another deeper layer of the exciting history of

Berkeley and I thank you

P

I just read Emmanuel Montoya’s historiography, it is not easy to weave history with biography, and here, in this blog, it has been accomplished in a most effective way. Juan Pablo Gutiérrez Sánchez