The Kingston Trio didn’t look scary. They looked nice. Cleancut. Safe. They did not look like communists or fellow-travelers. They looked American.

They achieved fame in the late 1950s, as the anti-communist hysteria of the early 1950s waned. They weren’t risk-takers, but they were not risk-averse either. While most of their early tracks were pure, apolitical folk songs, they did include in their debut album of 1958 “Wimoweh,” which the Tokens released as “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” three years later. It can be seen as a metaphor for Africa waking from its sleep and driving out colonial powers. It was part of the Weavers’ concert setlist.

In 1961, the Kingston Trio included Woody Guthrie’s “Pastures of Plenty” and “This Land is Your Land” on albums, two radical songs that five years earlier might have landed them in the red-scare soup. In 1962, they gave us “This Little Light” (a gospel song that had been adopted by the civil rights movement) and the anti-war “Where Have All the Flowers Gone.” Overlooked at the time was “Charlie and the M.T.A.,” included in their second studio album, released in 1959.

It was a safe-sounding song, but in fact it was a song with a bona fide radical heritage.

It was a safe-sounding song, but in fact it was a song with a bona fide radical heritage.

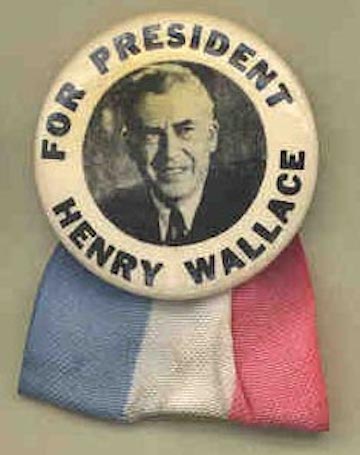

The Progressive Party came into being in 1948. At its founding convention, it nominated former Vice President Henry Wallace for President against Harry Truman.

Wallace and his party were concerned about the drift into the Cold War. Truman won. We know that, right? Wallace got just over a million votes, a few thousand fewer than Strom Thurmond running on a segregation platform.

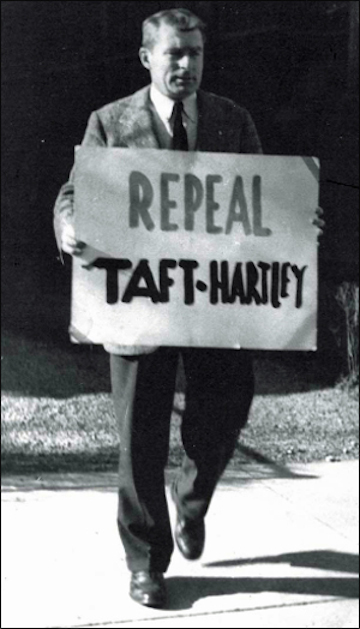

In 1949, the Progressive Party of Massachusetts nominated Walter A. O’Brien for mayor of Boston.

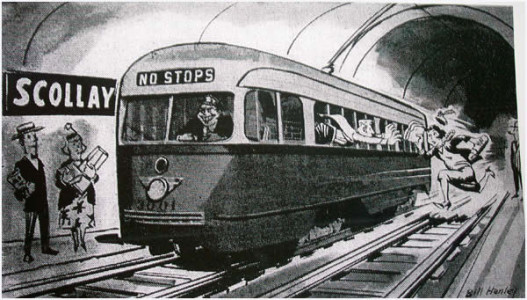

As a candidate for mayor, O’Brien pledged to fight fare increases on the M.T.A. His campaign was low on funds. As a budget measure, artists supporting O’Brien recorded seven songs which were played by sound trucks driving around Boston. Each song emphasized one component of his platform.

Which brings us back to “Charlie and the M.T.A.” The tune was an old one (“The Ship That Never Returned” and/or “The Wreck of Old #97”), but the lyrics were new.

Bess Lomax Hawes and Jacqueline Steiner wrote the lyrics. They urged voters to fight the fare increase and vote for O’Brien for mayor. The most radical verse was not all that radical – Charlie sighs “Well I’m sore and disgusted and I’m absolutely busted, I guess this is my last long ride.”

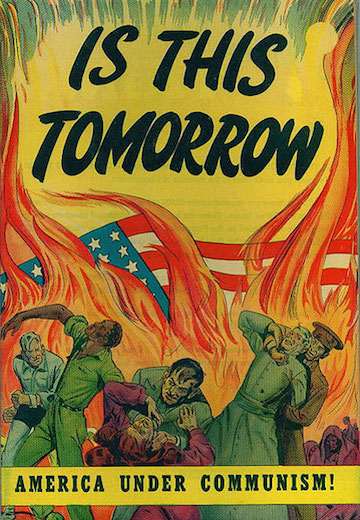

A folk singer named Will Holt recorded the song as a pop song for Coral Records in 1957. It took off on the charts but then – patriotism! Peter Dreier and Jim Vrabel tell us what happened: “Radio stations played it, record stores sold it. LIFE magazine even planned a feature story on Holt and the song, one that included photographs of Holt at the various subway stops mentioned in the song. Suddenly, though, radio stations stopped playing the song, stores stopped selling the record, and LIFE abruptly pulled its story. Why? With the Red Scare still a force, right-wingers had objected to the song for including the name of Walter O’Brien, and thus “glorifying” a radical.”

And then the Kingston Trio. They dropped the “sore and disgusted” verse and changed names to protect the innocent, urging listeners to vote for “George O’Brien.” No fuss, no patriotic protest. Just a cute song. But a radical song all the same.

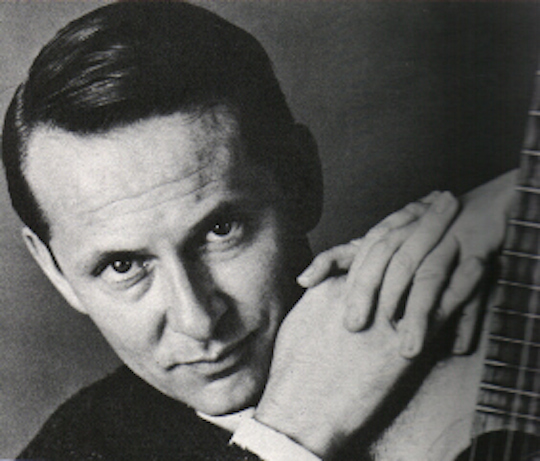

I went to show the photos to my friend.

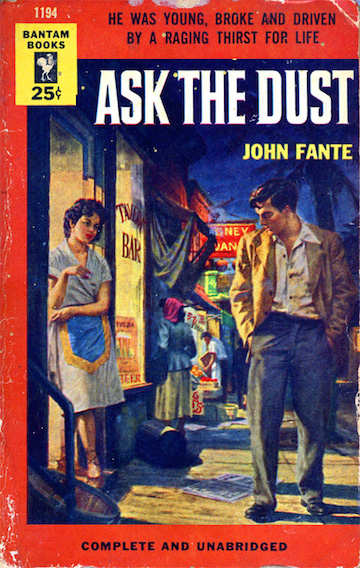

He was deep lost in John Fante.

He showed me photos of Los Angeles, depression era. Of which Fante wrote with such craft. These were all places in the book.

Okay. Good. Yes, I love images of LA in the 1930s. But what about folk music in 1959, what about Charlie?