On April 29, 2017, the Telegraph Business Improvement District celebrated the 50th anniversary of Berkeley’s Summer of Love (1967) with an all-day fair on Telegraph. Lots of tie-dye!

What was the best part? Hint: It’s all about me.

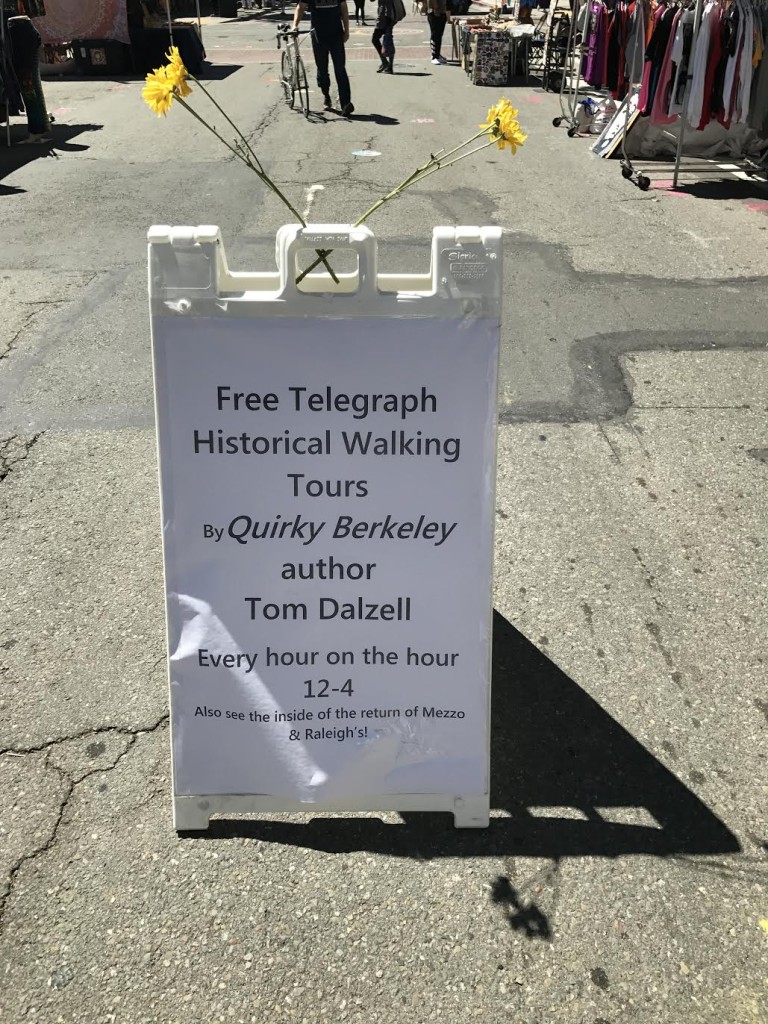

I led four one-hour walking tours of Telegraph from Bancroft to Dwight.

Here are two of the four groups:

My friend looked at this photo and said, “Dude on the right. Who’s that?” Harvey Smith. He wrote about New Deal work in Berkeley. Ninja-level Quirky Berkeley spirit. How did my friend spot/suspect/divine this? Don’t know. My friend has a way with things like this.

I also produced a funky little booklet about 1967 in Berkeley. I reproduce it here:

The Summer of Love

Berkeley1967

The term “Summer of Love” is thought to have been coined by the Council for the Summer of Love, created in 1967 by The Family Dog, the Straight Theater, the Diggers, the San Francisco Oracle, and about 25 individuals. Thus – counterculture roots for the term, not the mainstream press.

The most common association with “Summer of Love” is with our Big Sister across the Bay, thanks in part of Scott McKenzie telling us to wear a flower in our hair if we are going to San Francisco. Yes, Haight-Ashbury was an epicenter of counterculture in 1967, but we in Berkeley were no slouches. We hella rocked the summer of love vibe.

Just a year earlier, the Espresso Forum at Telegraph and Haste had briefly banned “longhairs.” By 1967, longhairs were coming to define youth culture in Berkeley.

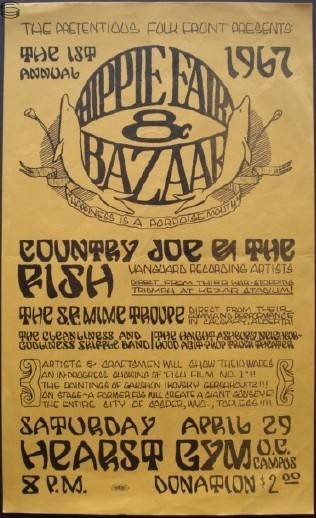

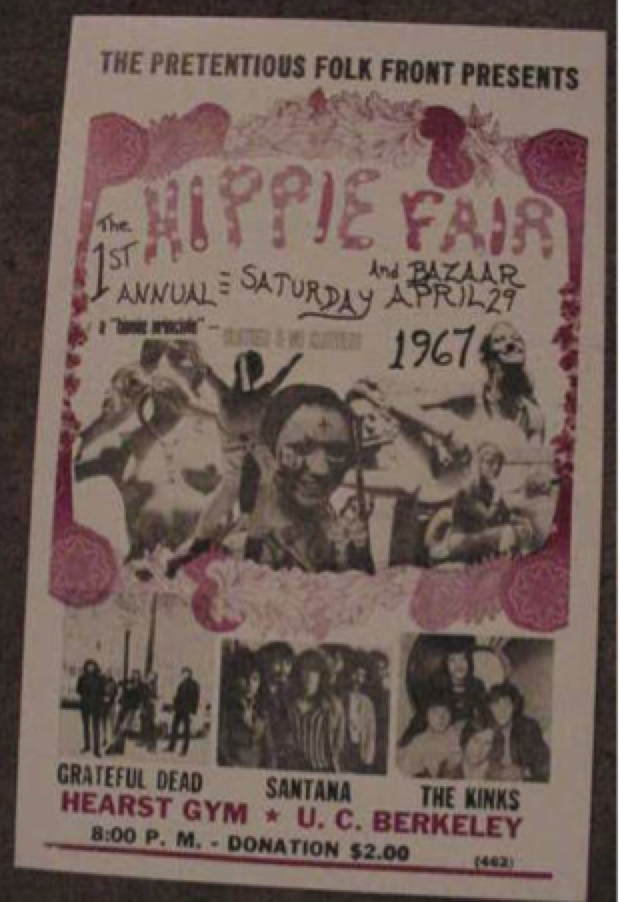

On April 29th, the First Annual Hippie Fair took place at Hearst Gym.

The Fair was promoted by ED Denson, founder of the Pretentious Folk Front. He managed local bands Joy of Cooking and Country Joe and the Fish

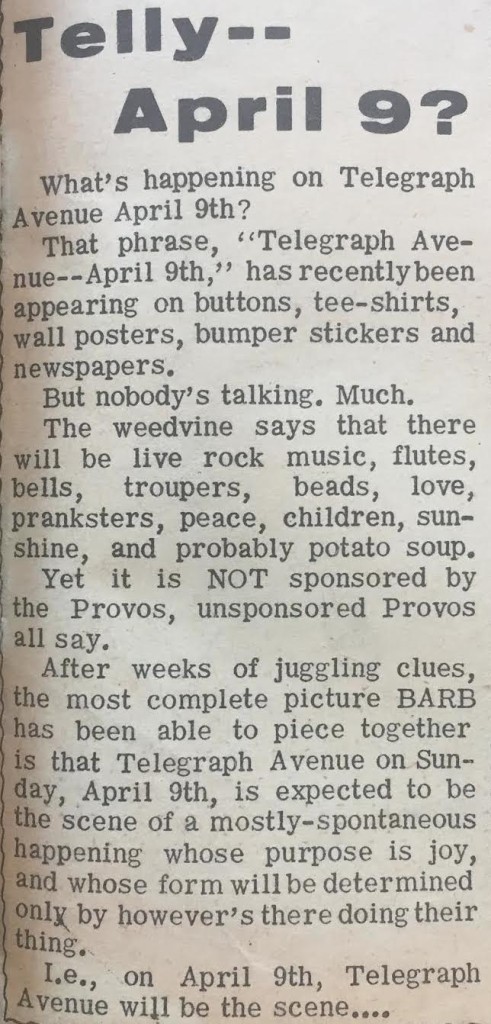

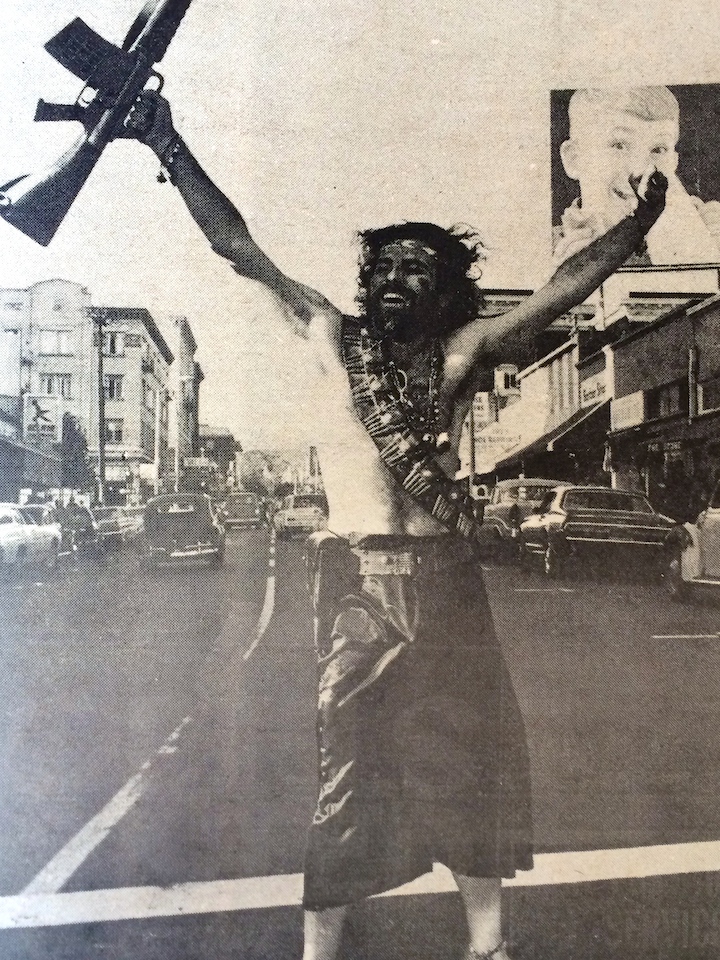

On April 9th, hippies had taken over Telegraph Avenue for several hours.

The April 7th Berkeley Barb predicted a “most-spontaneous happening whose purpose is joy.”

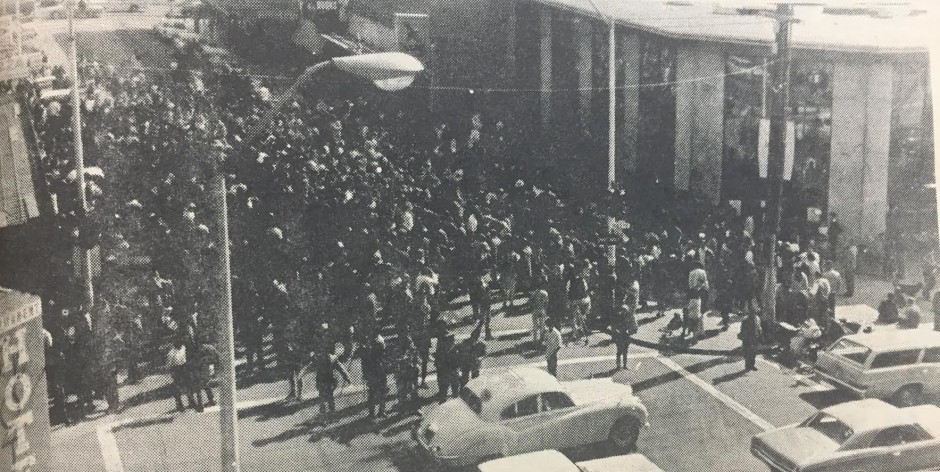

The “happening” was filled with joy as seen in these photos from the April 14th Barb.

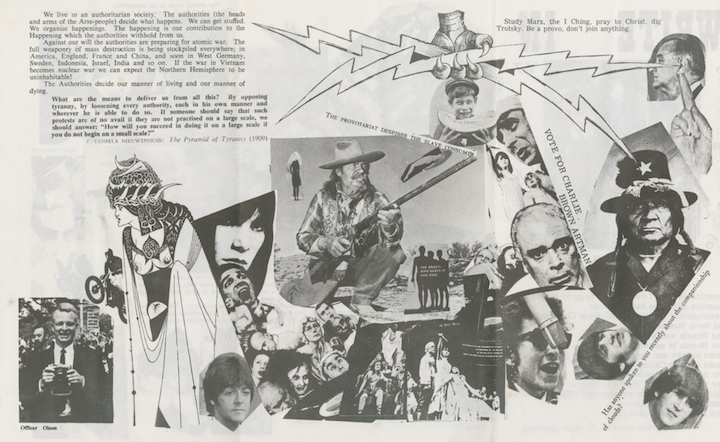

San Francisco had the Diggers, community anarchists, activists, and improvisational actors. They rejected money and capitalism. We had our Provos, named after a contemporary radical Dutch group. Bill Miller of The Store on Telegraph was one of the leaders of the Provos. The Civic Center Park was their base of operations, and the park came to be known as Provo Park for several years.

The Barb tracked the Provos throughout 1967.

On February 17th, the Barb reported that the Provos would do no more benefits, but that happenings would “continue on a sporadic basis.” The Provo program of free food continued, and “all souls interested in contributing food” were asked to step up.

The March 24th Barb headline read “Provo’s Sunny Silver Be-In,” and the article taught us that the official name of the be-in was “The Reversal of Earth Silver Be-In.” As the Provos did their hippie thing in Provo Park, about 350 people “paraded slowly in front of the City Hall, vigiling against the war in Vietnam.”

Both photos are from the March 24th Barb.

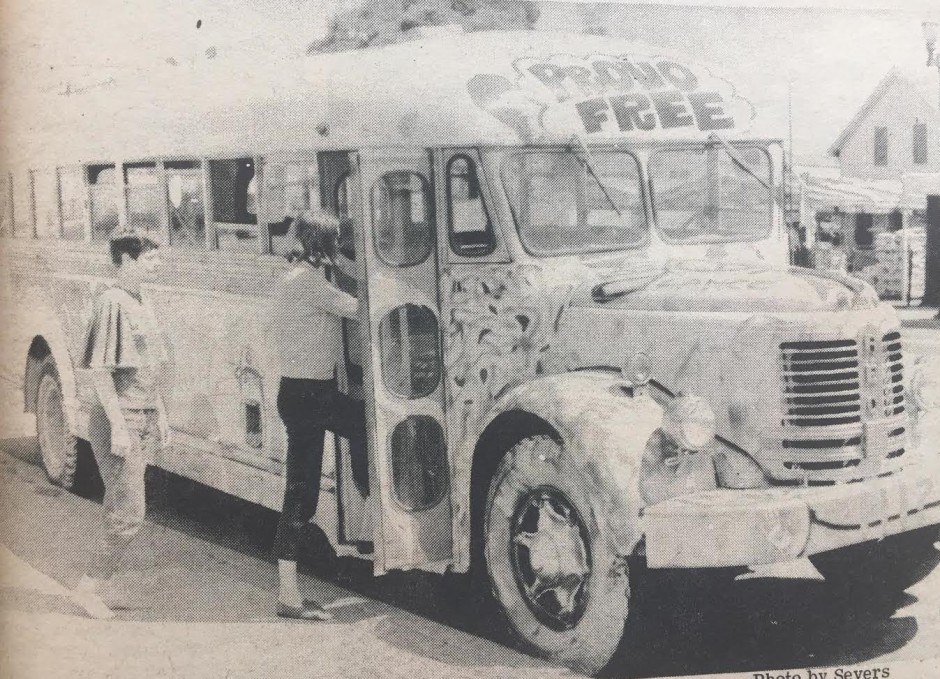

In the July 21st issue, we learned about the Provos bus, the Nova Express Love Provo Free Bus.

It ran irregular service to San Francisco, and the previous Sunday had taken a bus load to Canyon for a festival. “People sang, played with tambourines and recorders, talked to each other, laughed, sat on each others laps, cheered the bus uphill, talked of passing cars, shared cigarettes, and more.”

The Provos ran a free store at 2228 San Pablo Avenue, the current site of the Quince Café. The July 28th Barb reported that the store “needs food and mostly like money.” They were still serving soup, bread at pie at Provo Park every evening. The December 15th Barb told us that the daily soup moved indoors to the store due to cold, wet winds. The Provos also ran an “emergency crash pad” for the “temporarily roofless.” The store served as a mail pick-up place for those without a fixed address.

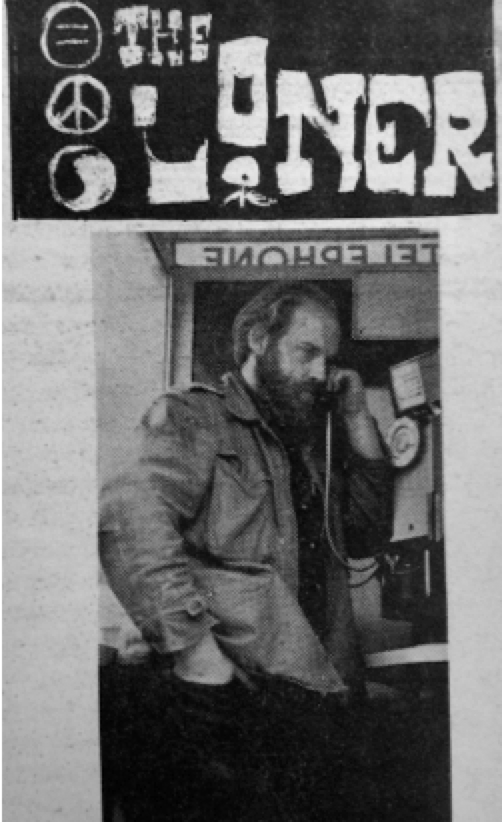

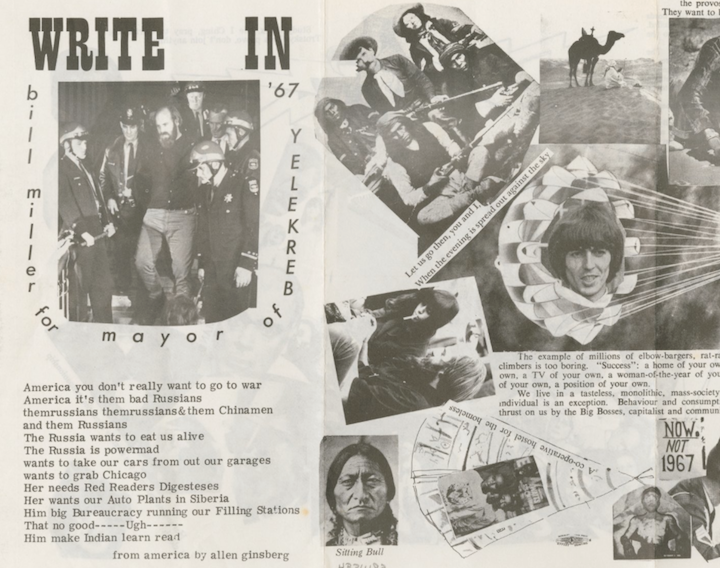

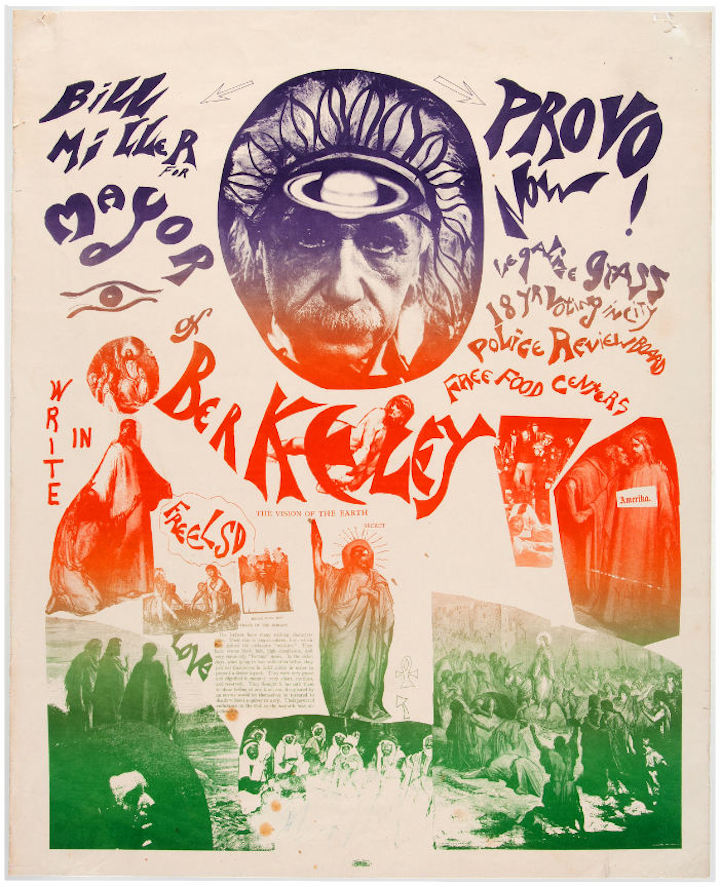

Bill Miller was visible on Telegraph with his General Store and was visible as the Provo candidate for mayor. For several months in early 1967, he wrote a column for the Berkeley Citizen, a short-lived newspaper with left credentials, but well to the center of the Barb.

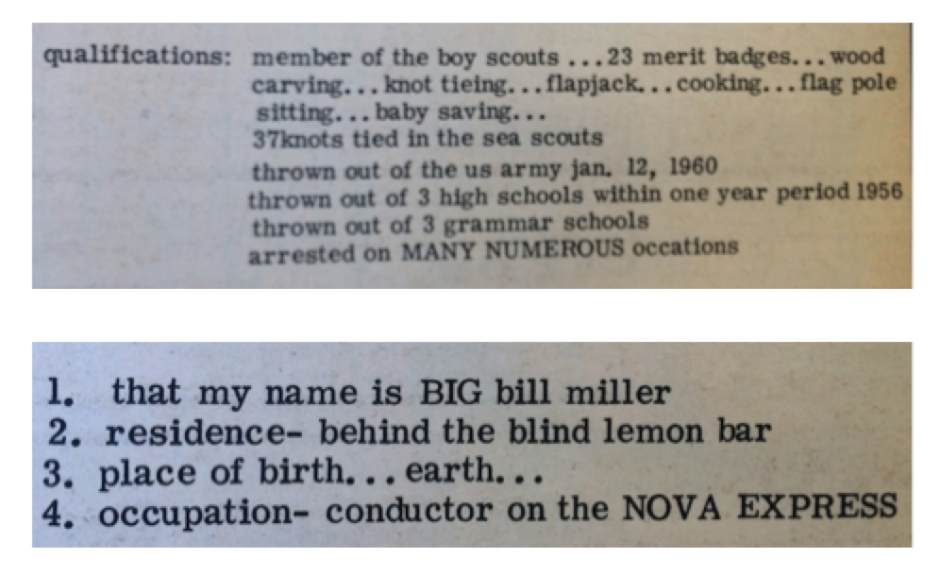

When Miller announced that he was running, he did so with tongue firmly in cheek. His campaign literature made his intentions clear.

He advertised in the Barb, he produced leaflets, he produced posters.

And as a result of all this work he got 61 votes. Out of 35,921. One tenth of one percent. He folded up and left. By 1969, Miller was back in Berkeley. He ran the Steppenwolf bar at 2136 San Pablo, which had once been owned by Max Scherr of Berkeley Barb fame. He ran for City Council in 1969. He improved substantially from his 1967 race, winning 2,548 votes, or 2.2% of the votes cast.

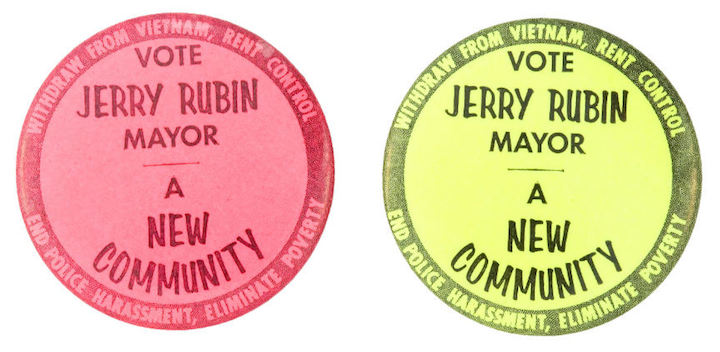

The second radical candidate for mayor in 1967 was Jerry Rubin, who had come to national attention as a leader of the Vietnam Day Committee, a very early anti-war group. Although Rubin was for a while from Berkeley, he doesn’t seem to have been an authentic product of Berkeley.

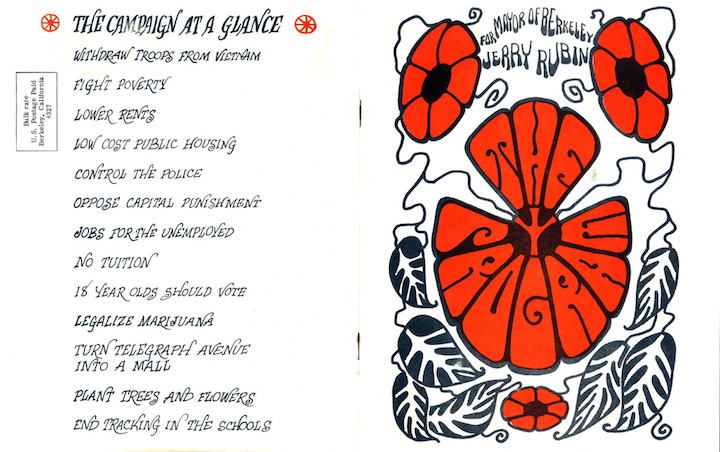

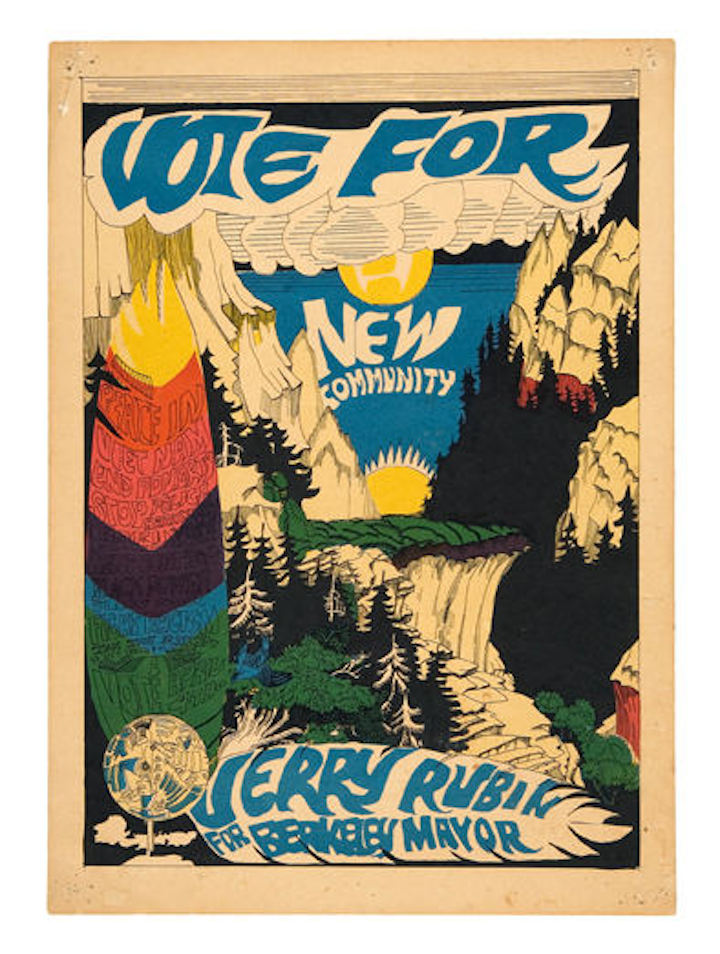

In any event, he ran for mayor in 1967. He produced literature.

He produced buttons. He produced a killer psychedelic poster.

Rubin famously ran on a platform in which he ventured that if he won, he could grant himself a pardon.

Rubin famously ran on a platform in which he ventured that if he won, he could grant himself a pardon.

In the end, he did better than Bill Miller, winning 7,385 votes or slightly more than 20% of the vote. Not bad for a crazed hippie who was about to become a yippie.

One progressive candidate who won in 1967 was Ron Dellums, who was elected to the Berkeley City Council. Bob Avakian, now the leader of the Revolutionary Communist Party, also ran for City Council. He lost.

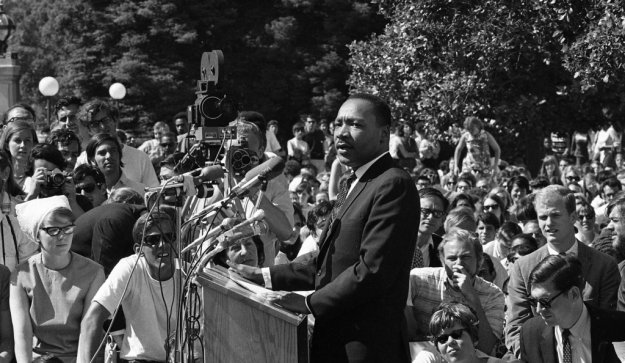

On May 17, 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke out against the Vietnam War on the steps of Sproul Hall. Thousands of students filled the area as Dr. King told them that they were the conscience of the nation.

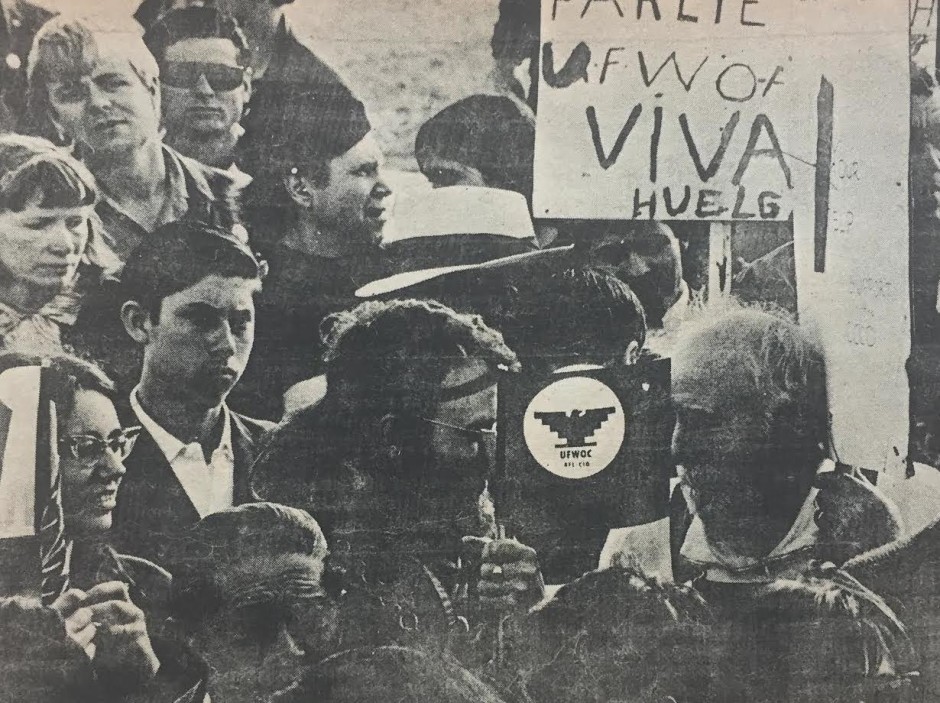

Meanwhile, farm workers in the San Joaquin Valley were two years into a grape strike that had evolved into a grape boycott. There were frequent updates on the strike and boycott in the Barb as well as pitches for support. The April 7th issue included a story about Charlie Brown, for several years a Berkeley prototypical hippie, visiting the United Farm Workers grape strikers in Delano.

And of course there was the anti-war movement. Berkeley had been on the vanguard of the anti-war movement with the Vietnam Day Committee, protests at the Oakland draft induction center, and efforts to block troop trains in west Berkeley.

By 1967 the anti-war movement had spread throughout the US, and Berkeley had to some extent tired of the anti-war movement’s evolution from its radical inception.

The March 3rd Barb reported that for the third Sunday in a row, “Berkeley peaceniks who have wanted to demonstrate their feelings about the Vietnam war without having to go to other cities or counties” had conducted a vigil in front of the Berkeley City Hall. Allan Paulson and Jane Friedman organized the vigil.

The Campus Mobilization Committee sponsored a series of events during Vietnam Week beginning on April 7th, culminating in a rally on April 15th.

“The Movement” was an amorphous but widely understood term in 1967 Berkeley. So – when Arnie Egel launched the Movement Library, we knew what he meant.

Headquartered above Moe’s, the Movement Library operated out of a 1942 Army ambulance and promised “Radical Literature Loaned Here Free. Easy to Borrow, Easy to Return.”

Headquartered above Moe’s, the Movement Library operated out of a 1942 Army ambulance and promised “Radical Literature Loaned Here Free. Easy to Borrow, Easy to Return.”

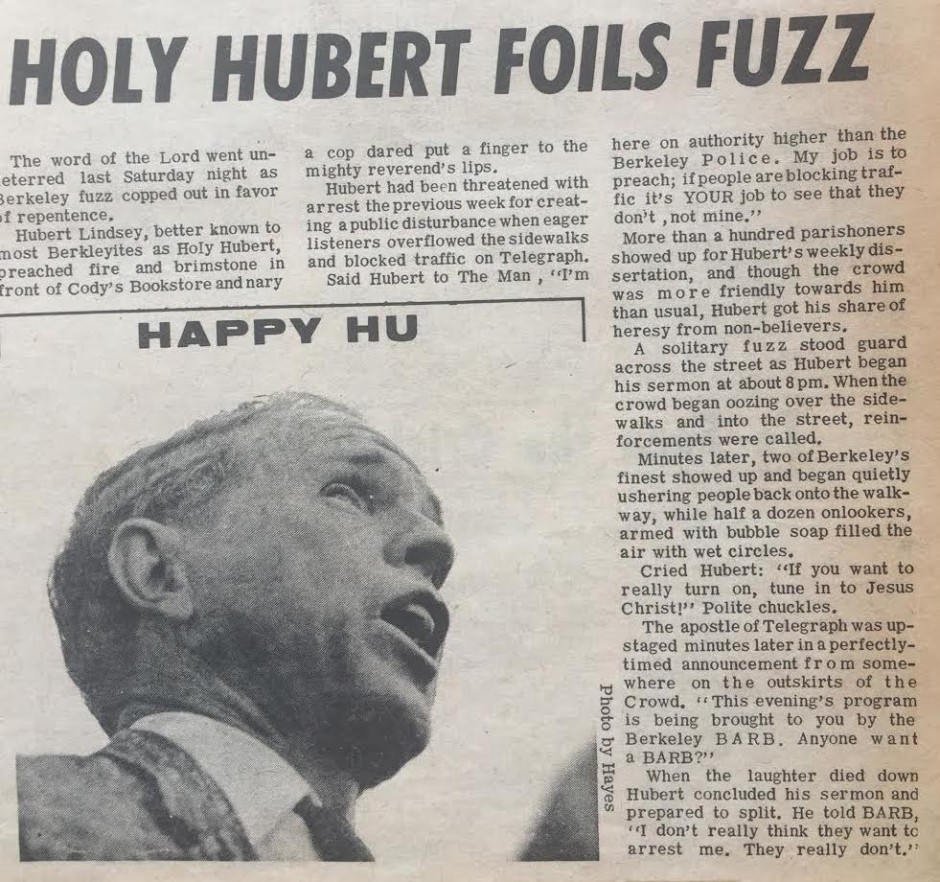

Religion was a presence on Telegraph in 1967.

Holy Hubert was the most flamboyant and self-promoting of the street preachers. His name just about says it all. Hubert Lindsey, born in Georgia, was a fixture preaching at Bancroft and Telegraph from the mid 1960s into the 1970s. He was in his 50’s when he started up in Berkeley. It is said that he fought the Hare Krishna’s for Sproul Plaza rights. Fought, as in fight. As in fisticuffs. He was an advocate of confrontational evangelism. Despite his religious conservatism, the Barb admired his spunk in this artcicle from the July 27th issue.

The Jesus Freak movement touched Berkeley, as shown in this January 27th article from the Barb. The Christian World Liberation Front (great Berkeley name!) was an offshoot of the Campus Crusade for Christ. It targeted “the radical forces of darkness” in Berkeley and on Telegraph.

It was led by Jack Sparks. In the 1970s Sparks and the CWLF started an assault on “spiritual counterfeits.” He eventually joined the eastern orthodox movement.

The Most-Berkeley religious presence in Berkeley in 1967 was the Free Church of Berkeley. Richard York (“the hippie priest) and the Berkeley Free Church ministered to the needs of Telegraph’s young street people-hippies-runaways-prematurely homeless. The church was originally sponsored by Berkeley merchants as the South Campus Christian Ministry.

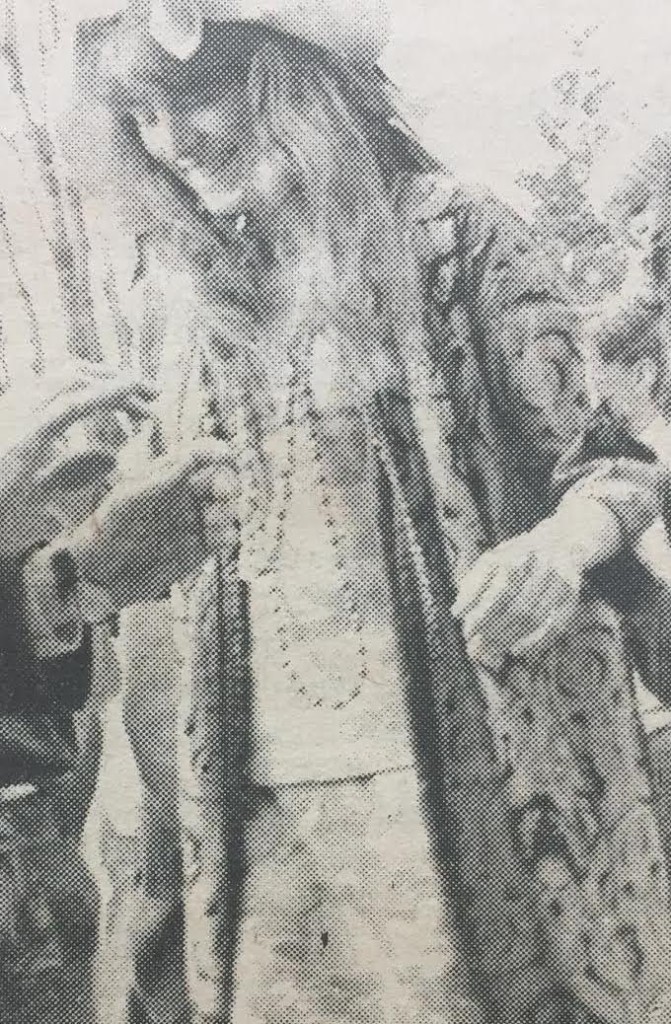

This photo was taken on August 12, 1967, during the Festival of the Virgin Mary on Haste Street. During the celebration (a religious be-in), York (with the frizzy hair) washed the feet of 12 hippies. He later wrote” Then we started washing hippies’ feet with big buckets of warm soap water and towels, in all these big vestments. It just blew these freaks minds. Cause, here were all these clergy washing their feet – which is just what it was all about.”

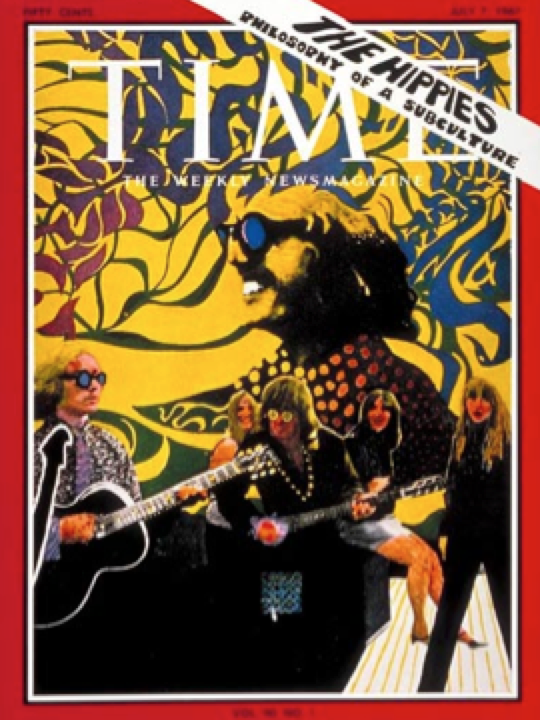

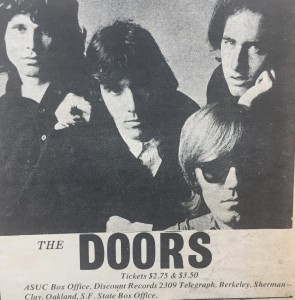

San Francisco dominated the emerging psychedelic rock scene, but Berkeley had a robust music scene of our own.

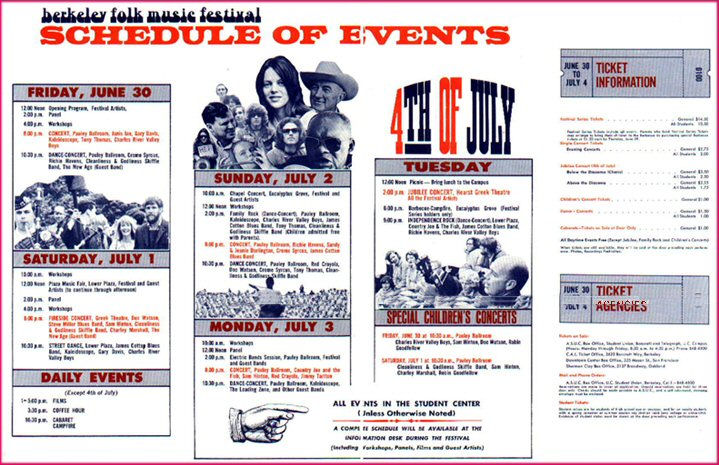

Berkeley was one of the major centers of the American folk music revival in the 1950s and 1960s. The Berkeley Folk Music Festival was held each year from 1958 until 1970, directed by Barry Olivier.

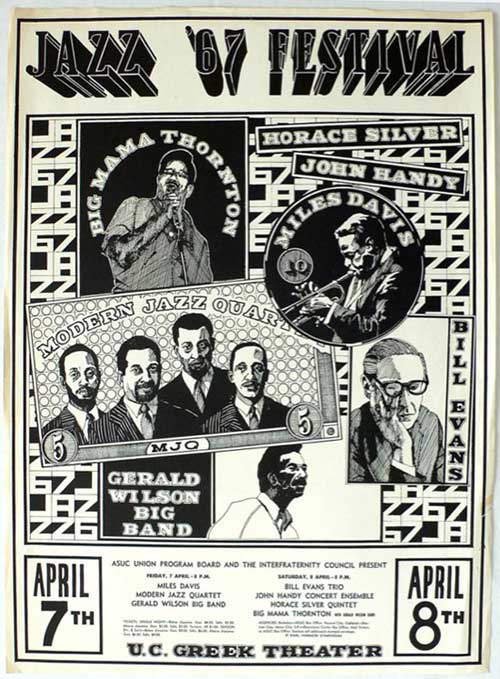

Not to be outdone, the Berkeley Jazz Festival was launched in 1967. The first festival was held April 7–8 at the Greek Theater. Friday evening saw sets by Miles Davis, The Modern Jazz Quartet, and the Gerald Wilson Big Band. On Saturday, the Bill Evans Trio, the Horace Silver Quintet, the John Handy Concert Ensemble, and Big Mama Thornton performed. Ralph J. Gleason, columnist of the S.F. Chronicle, was friend and advisor to the festival.

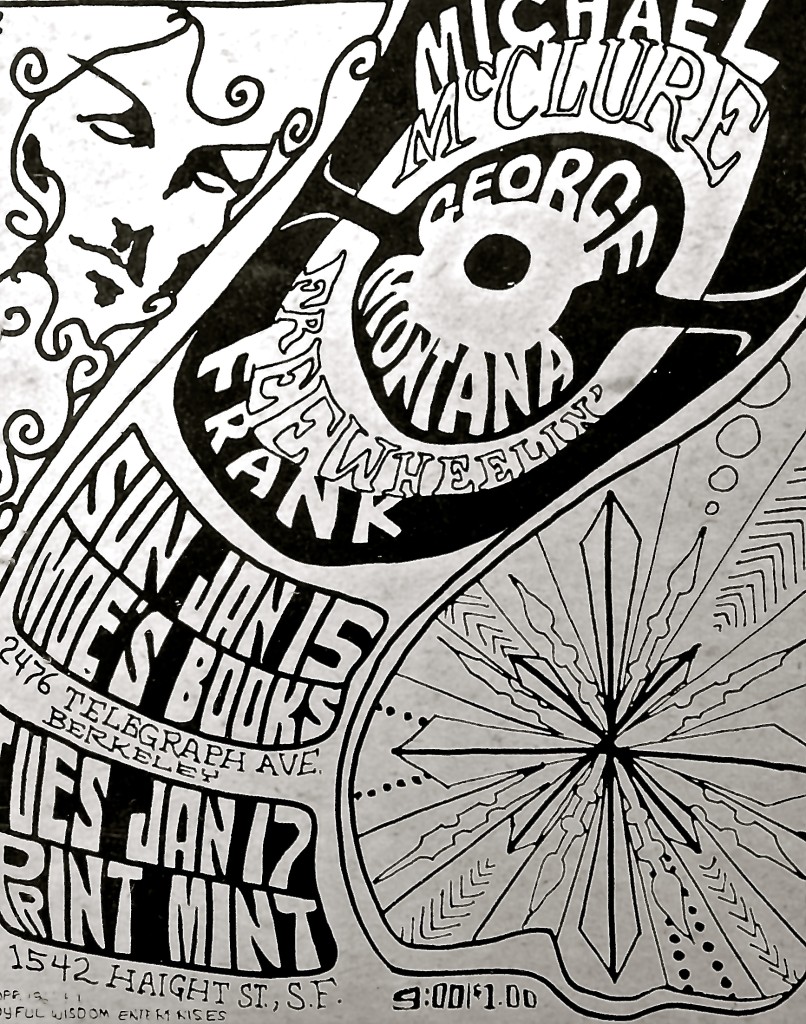

There were venues throughout Berkeley for rock and folk acts. They included Moe’s Books:

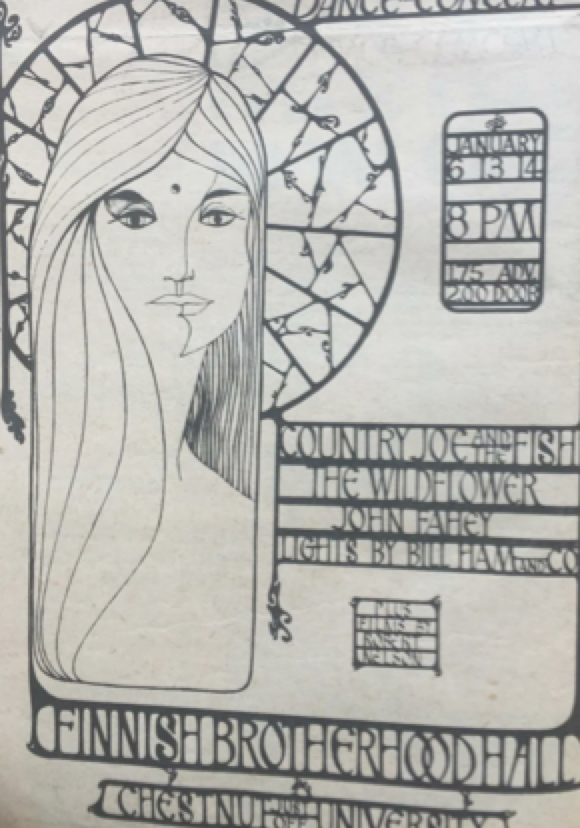

The Finnish Hall:

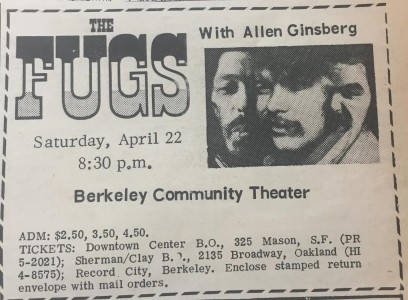

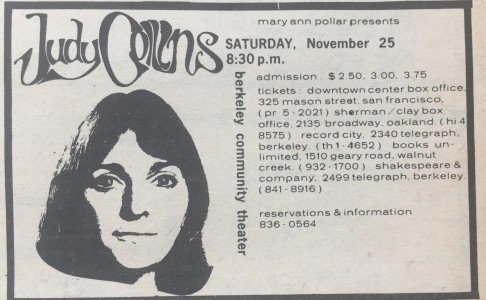

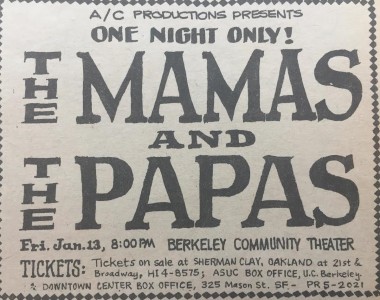

The Berkeley Community Theater:

The New Orleans House:

Where there were big names of rock bands, there was trouble to be had.

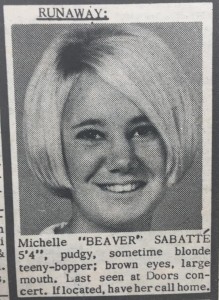

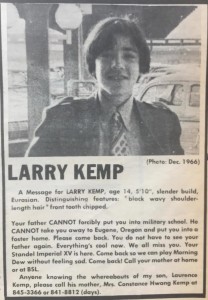

Berkeley was a magnet for teenage runaways, and as one of these Barb classified ads, rock concerts were often launching pads for runaway careers.

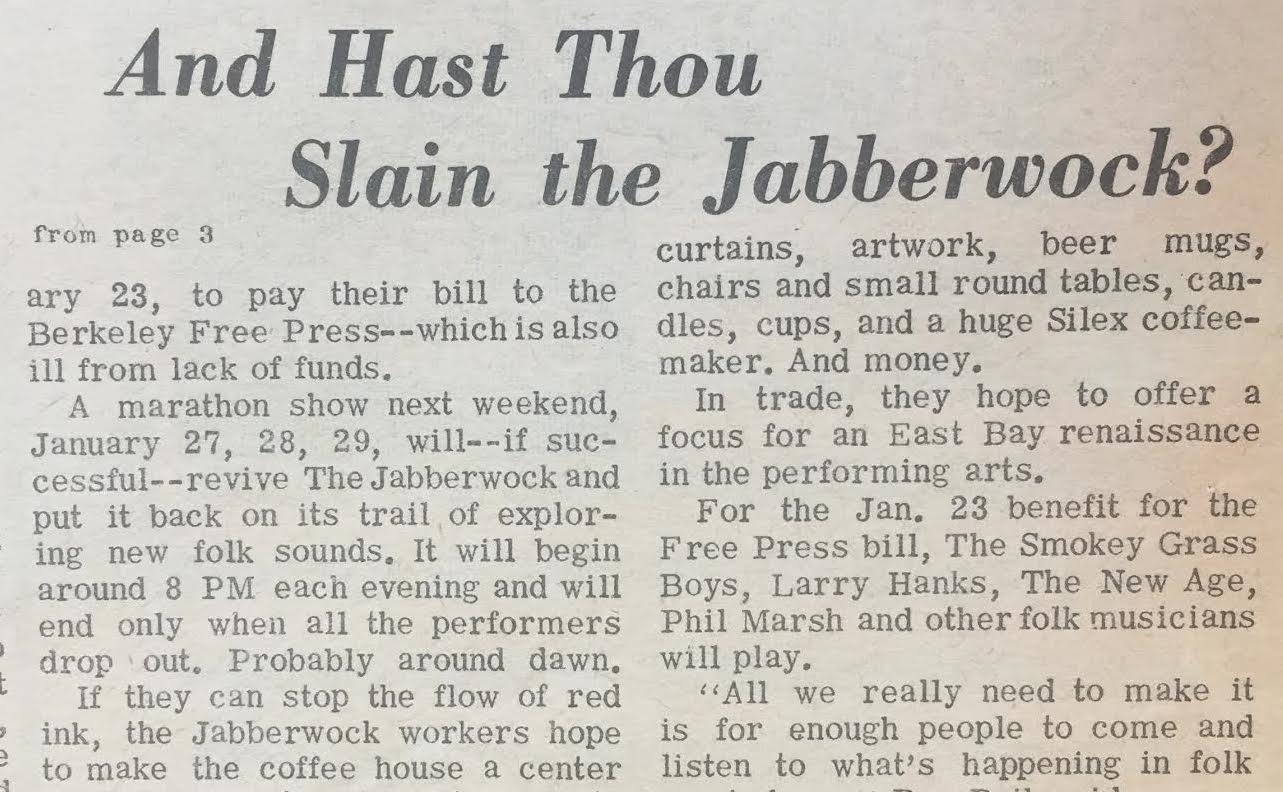

The major music event in Berkeley in 1967 may well have been the closing of the Jabberwock, a folk music club at Telegraph and Russell that was a popular venue in the Bay Area folk music scene.

It opened in 1963 and closed in 1967, as announced in the July 7th Barb:

It was the home hall for the band that would soon emerge as Country Joe and the Fish.

A few more notes on Berkeley in 1967, in no particular order.

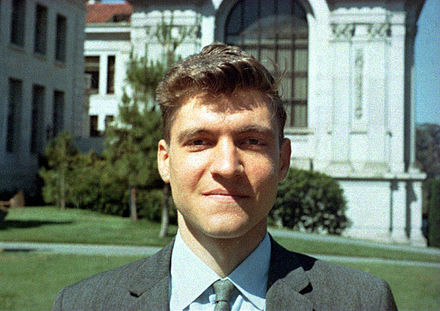

A young Ted Kaczynski, who in 1967 became an assistant professor of mathematics at Cal, where he taught undergraduate courses in geometry and calculus. He is better known by his newspaper nickname, The Unabomber.

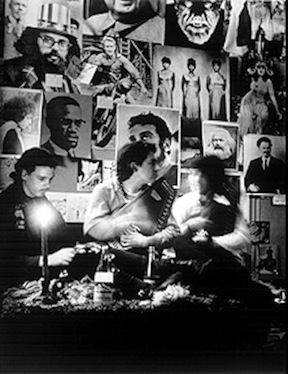

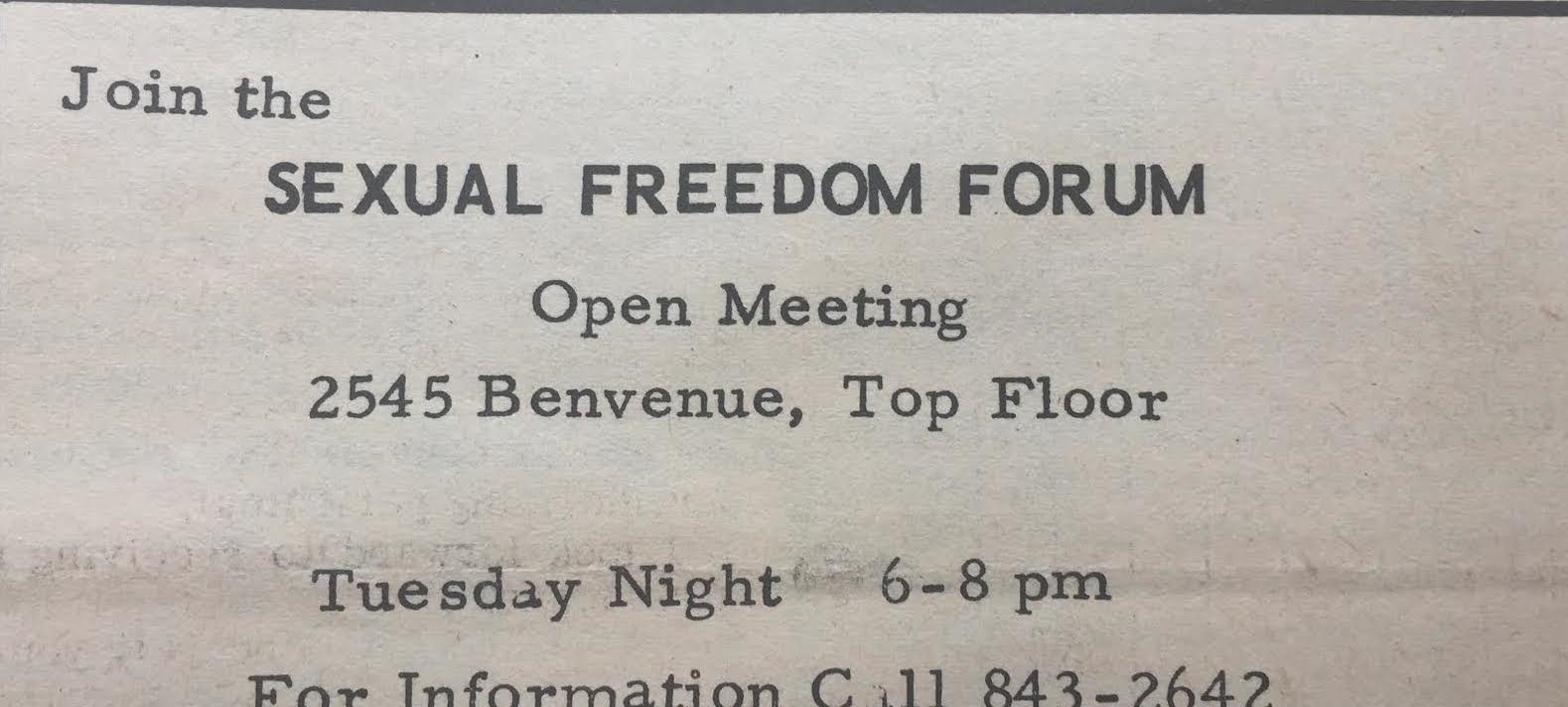

The Sexual Freedom League was an organization founded in 1963 in New York City by Jefferson Poland and Leo Koch.[1] It existed under the name New York City League for Sexual Freedom to promote and conduct sexual activity among its members and to agitate for political reform, especially for the repeal of laws against abortion and censorship, and had many female leaders. The Berkeley chapter was for several years the poster child for the organization. It faded, and the last of its 28 nude parties took place on Christmas Eve, 1967.

We began to be concerned about what we were eating. Attention was paid the organic food with at least one commercial outlet.

The Co-Op was located in the space now occupied by Sacred Rose on University.

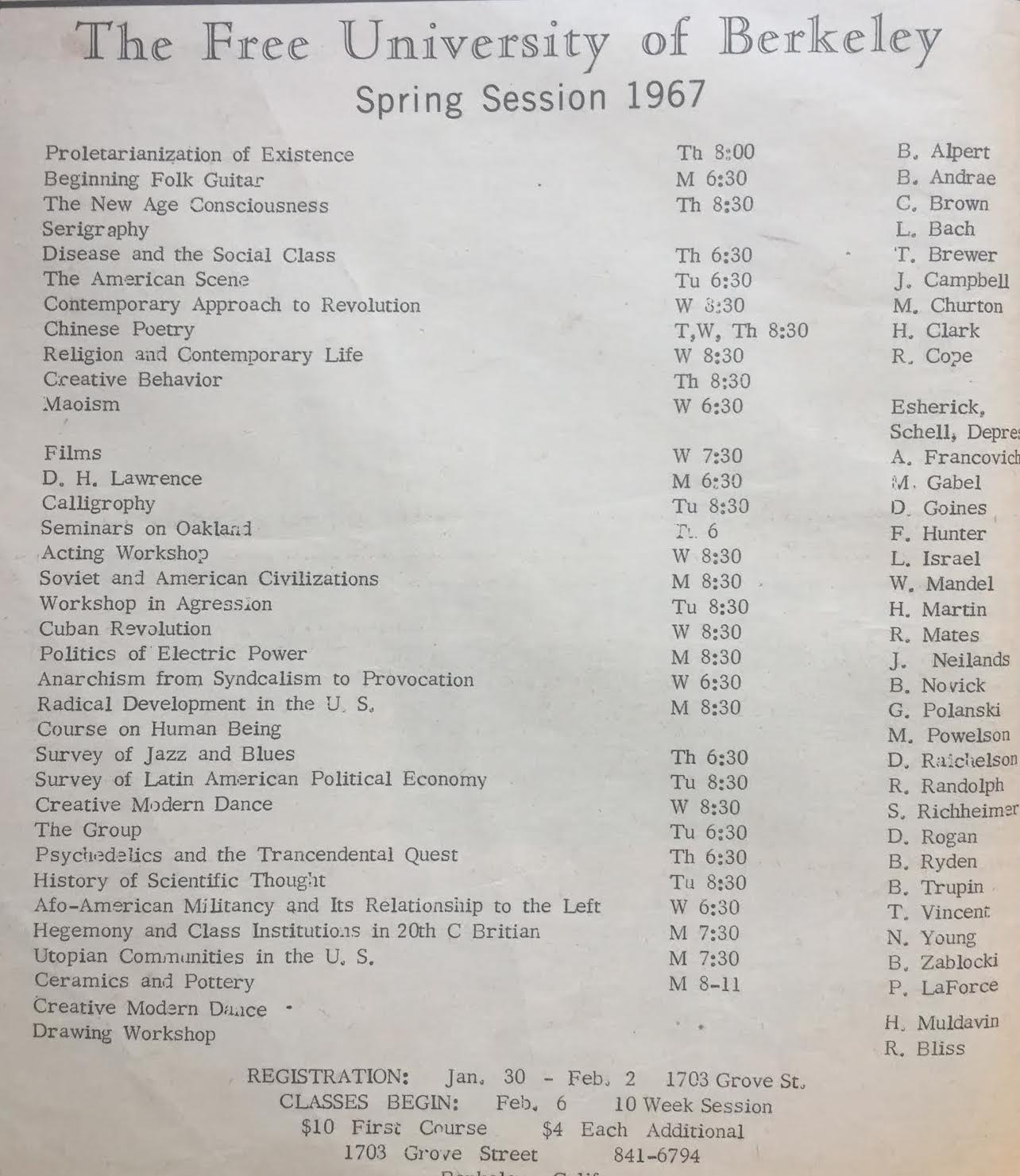

The Free University of Berkeley first offered courses in early 1966. Diverse courses were offered without a fee.

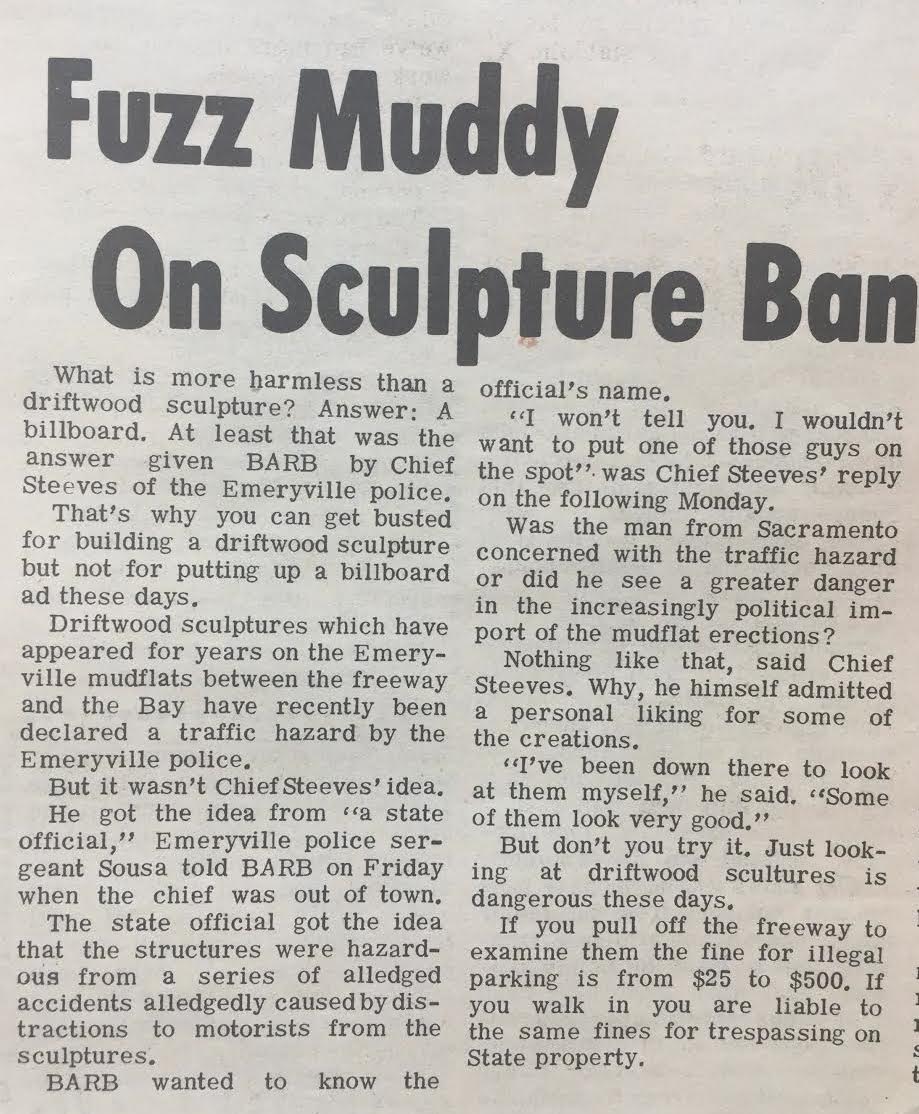

Last and NOT least, the driftwood sculptures in the Emeryville mudflats were going strong.

Law enforcement was starting to crack down on the sculptures, which had been appearing since at least 1960, but not from the environmental perspective which led to their demise. Foot traffic out to the flats put birds at risk and toxins leaching from the wood weren’t helping the health of the area. Caltrans started discouraging new pieces and dismantling existing pieces in 1986. In the early 1990s a fence came up and the Eastshore Park was born.

So there it was – 1967, in Berkeley. Snapshots. A scrapbook. A little bit of history.

My friend got emotional looking through these photos. He was here in ’67. He had no time for the Haight Ashbury scene. No time at all. But the Berkeley of those years, well, yes, they were good years for him. He claims to have been an on-again off-again driver of the Provo bus, a claim which I tend to believe.

Fifty years is a long time. Berkeley has changed a lot and many times since then. Some of us, not many but some, still carry the spirit of ’67 with us, whether we were here or not. Sure, there were counter-productive excesses. But there was something to believe in, to fight for. There is still a little spark of this in Berkeley. I look for that spark and warm my hands over it.

What does my friend think of what I put together?

WAIT – What is this? His long-lost identical twin brother Earl? Visiting from Flint? WHY DID I KNOW NOTHING ABOUT THIS VISIT?????? There HAS to be a story here.

Dear Tom,

Great site and great account of 1967 in Berkeley. I am a collector of Provo material (magazines and pamphlets – see web site) and would love to put material of the Berkeley Provos on my site. It would be wonderful if you would have scans of Provo magazine covers, leaflets, or posters that you can share. If you have any of these for sale then I would be interested in buying as well.

Best regards, Jan

Jan –

Great to hear from you. I neither have nor have ever seen Provo materials. What is your website? Would you like to write a guest post for Quirky Berkeley about the Provo movement? I can also get it placed in Berkeleyside.

Let me know – Tom

Dear Tom,

Totally missed your answer to my mail, almost a year ago. Before I commit to writing something for Quirky Berkeley (if the offer still stands), I would like to know what you expect in terms of length etc.

My web site is: http://www.provo-images.info.

Still very interested in any Berkeley Provo material you would come across.

Please write to me at my email address (jpen@planet.nl).

With best regards, Jan