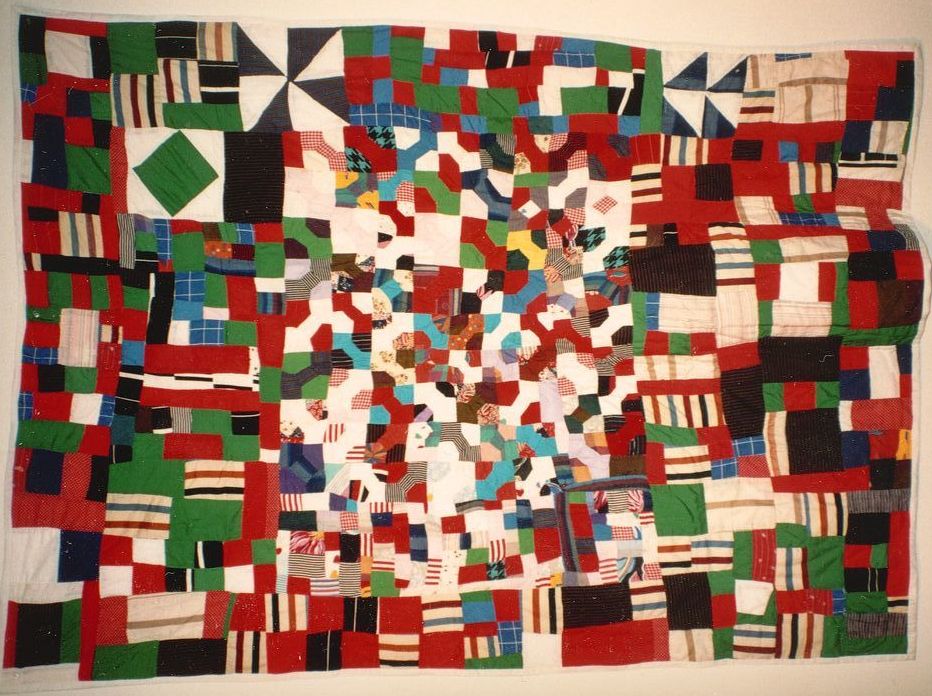

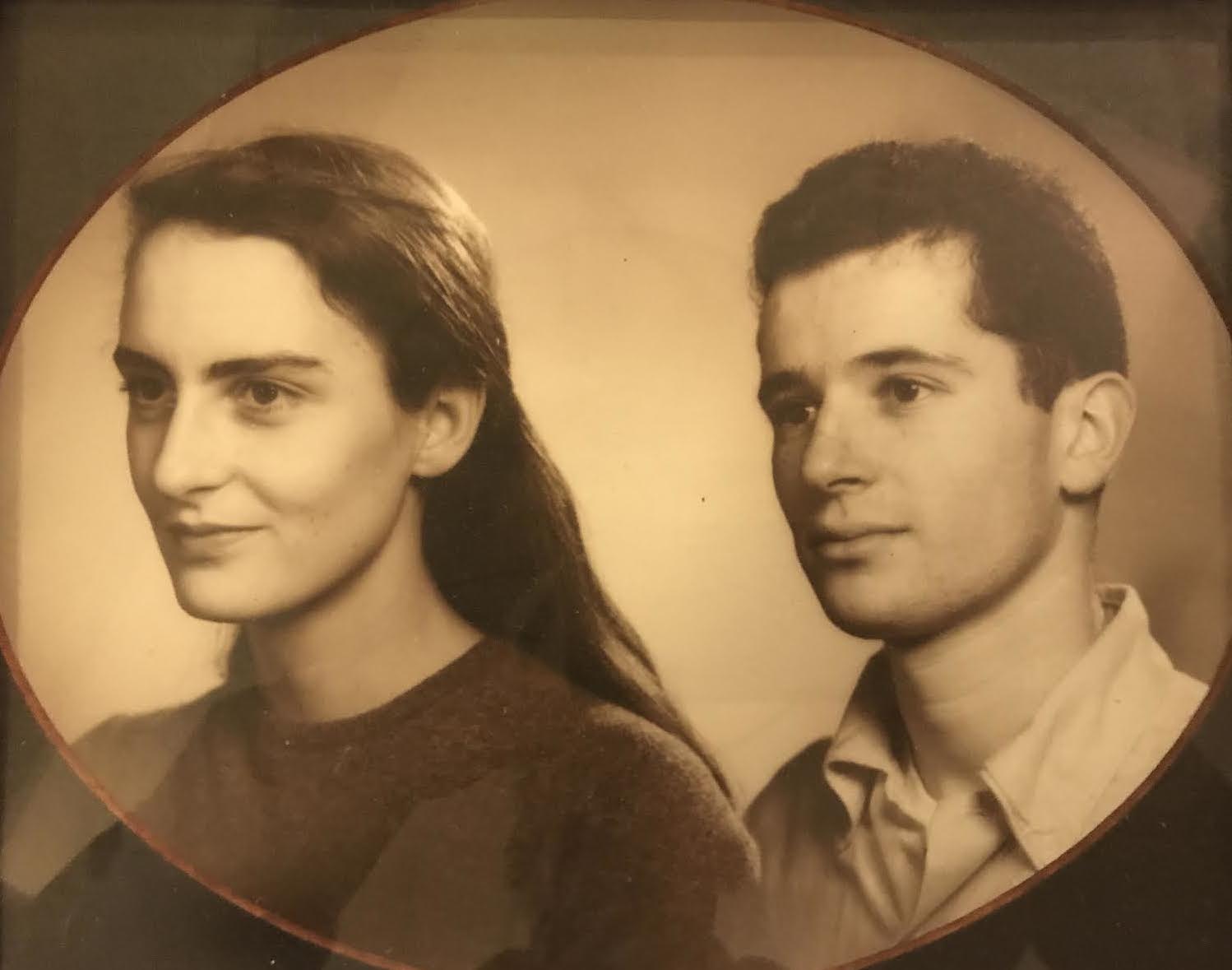

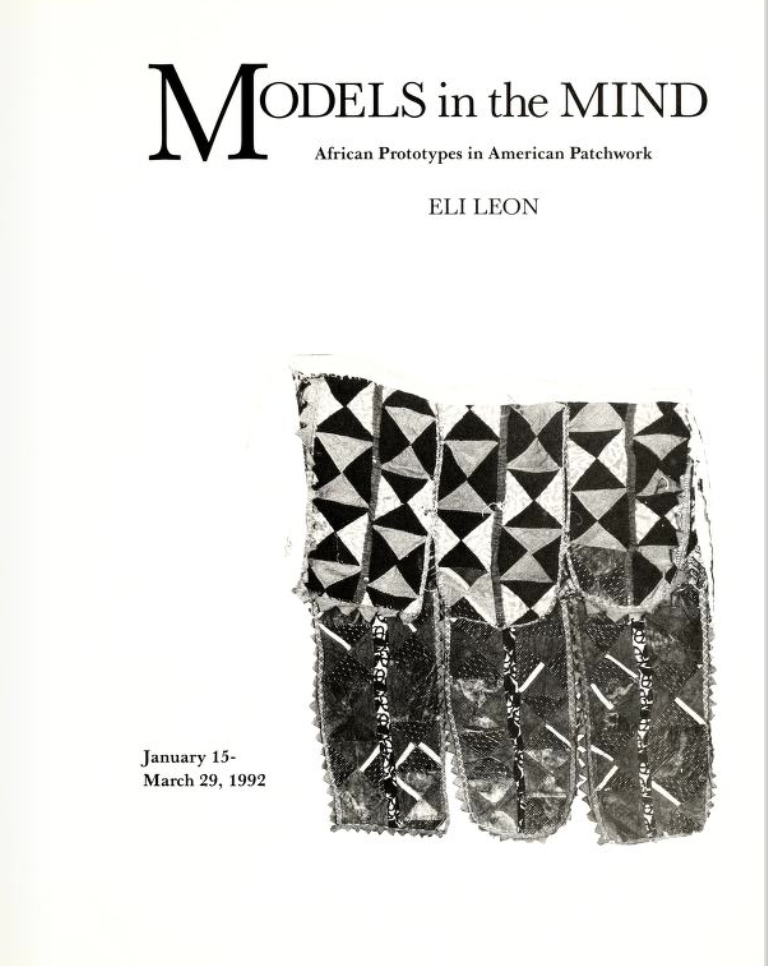

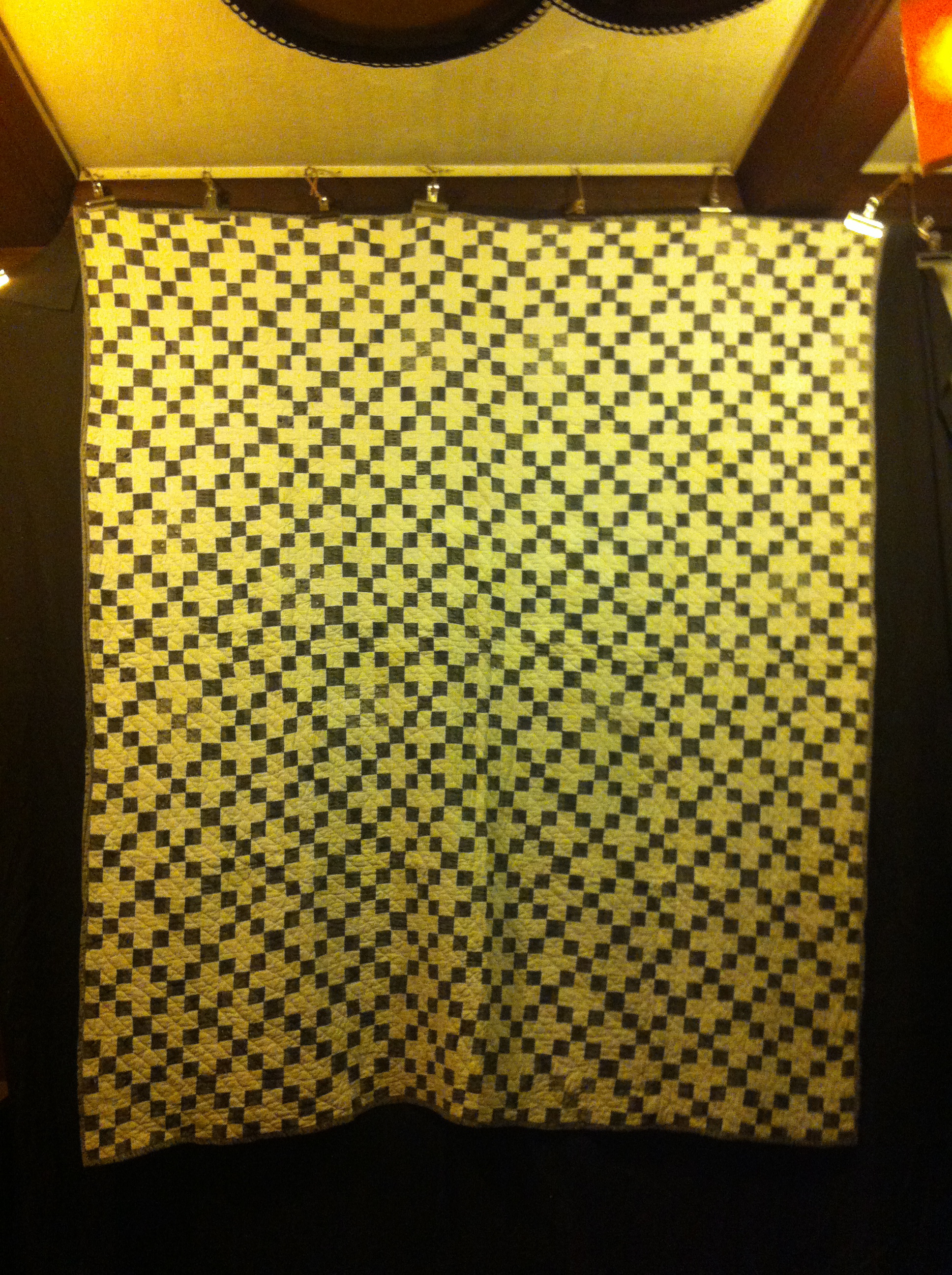

Bow Tie Medallion. Pieced by Kattie Pennington, Center, Texas, 1985. Quilted by Irene Bankhead, Oakland, California, 1990. Photo: Elileon.com

I don’t know Eli Leon. He is alive but not in our world, at least as far as we understand it. His collections are astonishing. He is best known for his scholarship about and collecting of African-American quilts, but his collecting far surpassed simply the quilts.

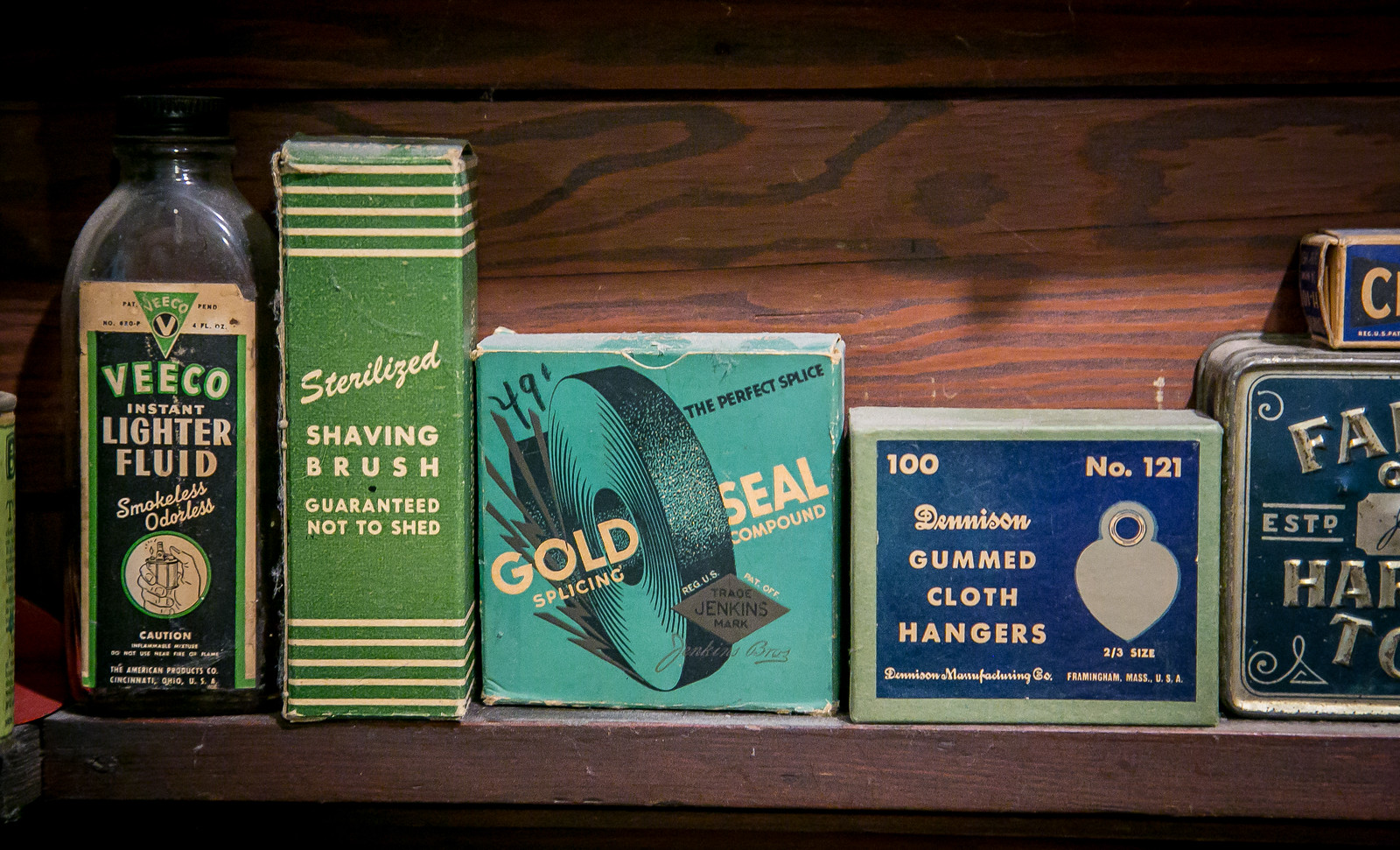

A story that he tolerated is that during construction of Interestate 580 (the Grove Street Freeway) in the late 1960s, Leon went through homes that had been eminent domained and abandoned, scooping up the everyday things of a working class neighborhood, which became the nucleus of his collection.

Later this month his living trust will sell off most of his collections. I visited his home in late May, before the estate sales group took over. His spirit lingers in the house.

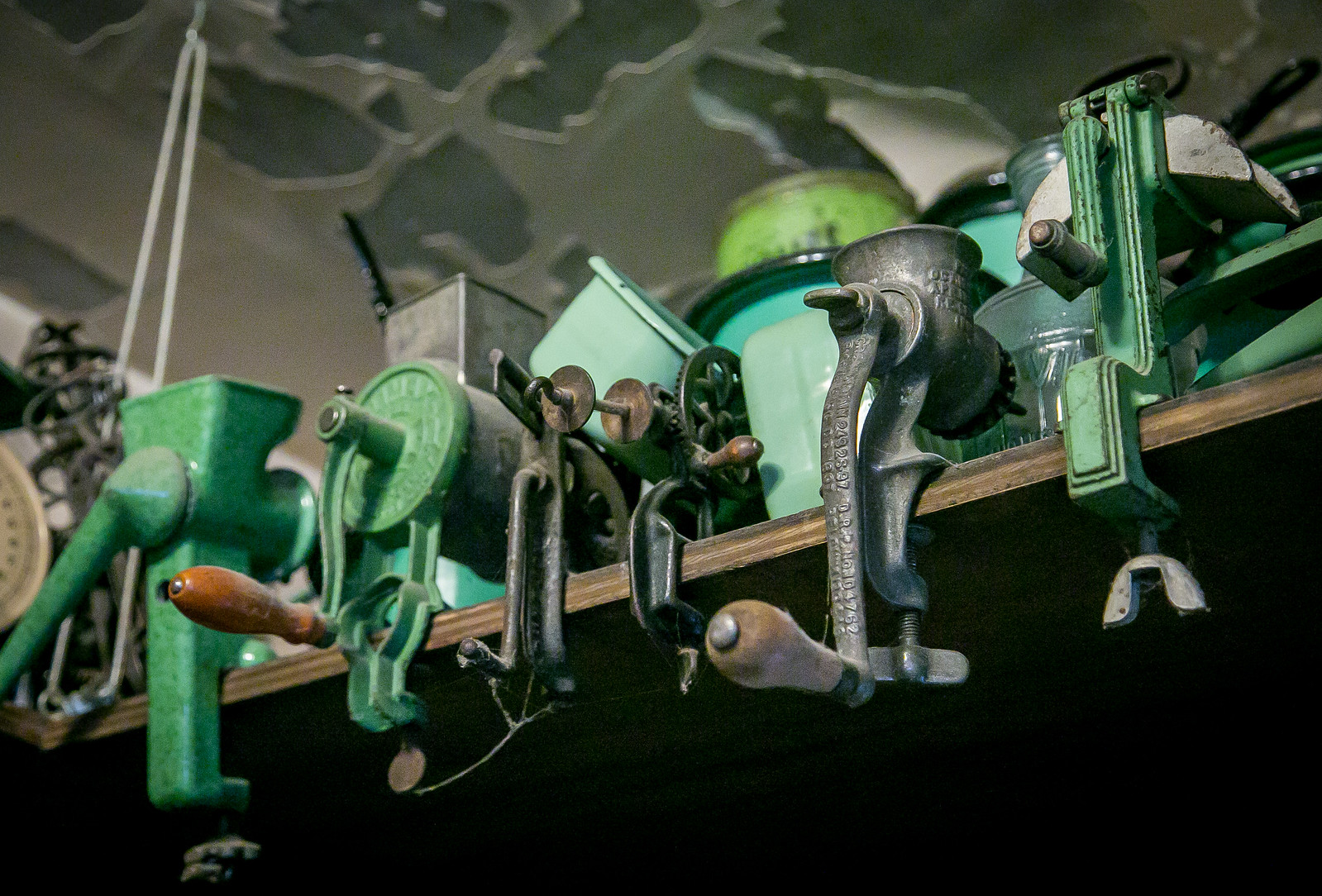

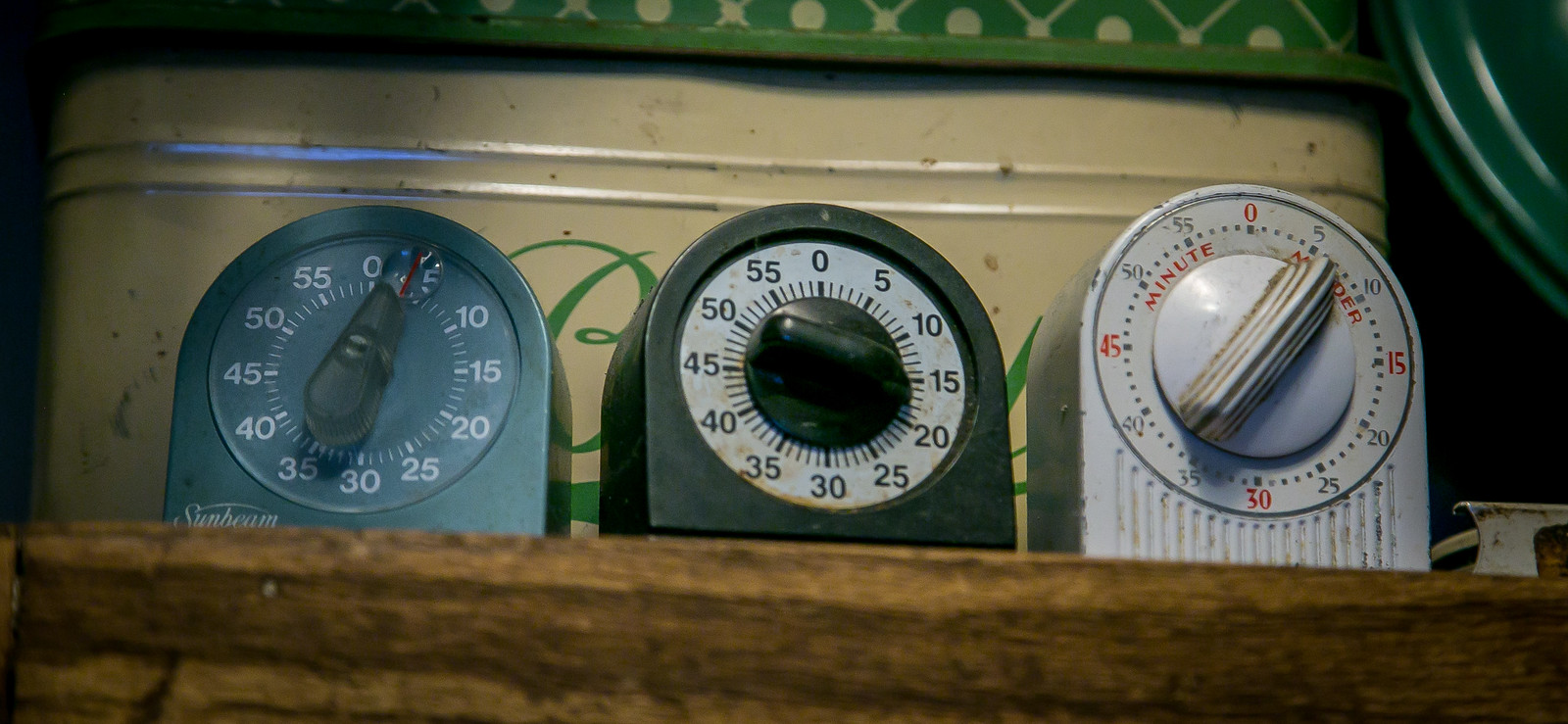

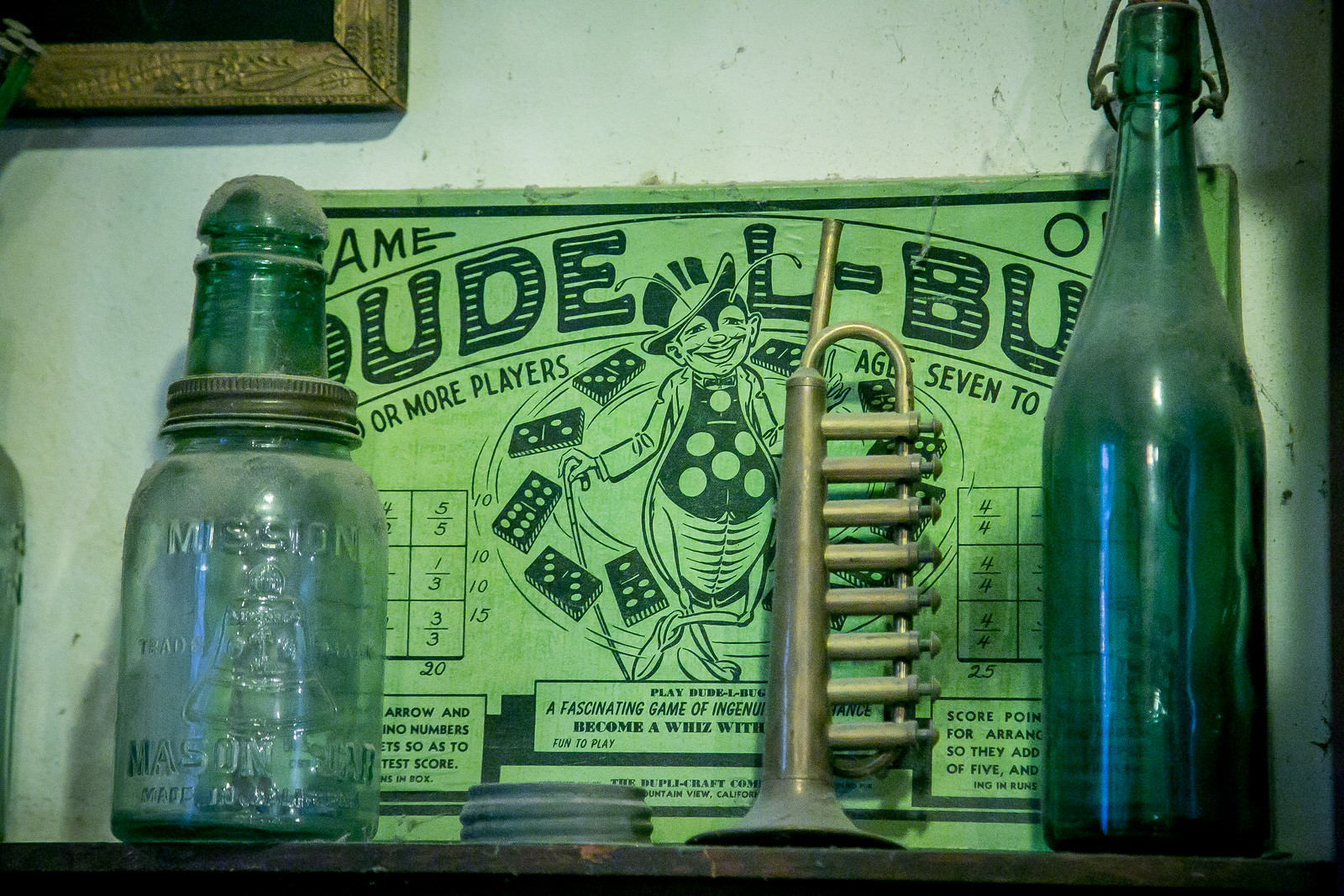

The main collections are in the kitchen and what was designed to be the dining room. Starting in the kitchen:

Stepping into the kitchen, you observe (1) Leon has a fondness for the color green; and (2) Leon has dozens, if not scores, of meat grinders.

There are many other antique kitchen contrivances and packages/advertising.

The dining room confirms Leon’s love of green and his eye for selecting and arranging disparate objects.

Leon was drawn to domestic arts, and throughout the house are trivets, many crocheted over bottle caps.

If there is a drawer, there is a drawer-full of treasure.

Lastly – for now at least – in the dining room is this hanging light.

Green! Love it!

The bathroom, not used since Leon moved out of his house in November 2016, still rocks a quirky vibe.

That’s some stuff, no?

Let’s look at the highlights of Leon’s life and his main event/main arena, quilt collecting.

Eli Leon was born in 1935 to Benjamin and Sylvia Leon, Lithuanian Jews who lived in the Bronx. They called Eli “Bobby.” After his father died, Leon telephoned his mother every day.

A lifelong friend, Simi Berman, writes:

I’ve known Eli since our first days of High School at the High School of Music & Art in NYC. Not only were we in the same homeroom class but we lived in the same neighborhood so often travelled home together.

It was always so easy to talk to him about anything at all because he was so open his own quirky self. In fact he had many close female friends with whom he stayed in touch with for his entire life.

Eli was an art student and in the creative vanguard of our class with his many gifts. A writer of poems and other assorted other observations, he was on the school literary magazine.and had a great eye for graphics.He also worked in ceramics. Apparently already back in 7th grade his art teacher was giving him special time and attention to do individual art projects and this was public school in the Bronx!

One summer shortly before he graduated,he went off to Black Mountain College, the avant guard art college in North Carolina, to work with Karen Karnes in the ceramics department.

One of his friends remembers studying for a physics test together and his coming up with the idea of trying to understand the workings of a combustion engine by acting out with, with his fellow students, the different parts of the engine.

The only specific memory I have is of a nighttime walk with him across a stretch of the as yet unopened Major Deegan highway. There was a ribbon of asphalt stretching out in the moonlight as we walked across Van Cortland Park to Riverdale where I used to go to school. It is typical of the interesting things he thought of doing.

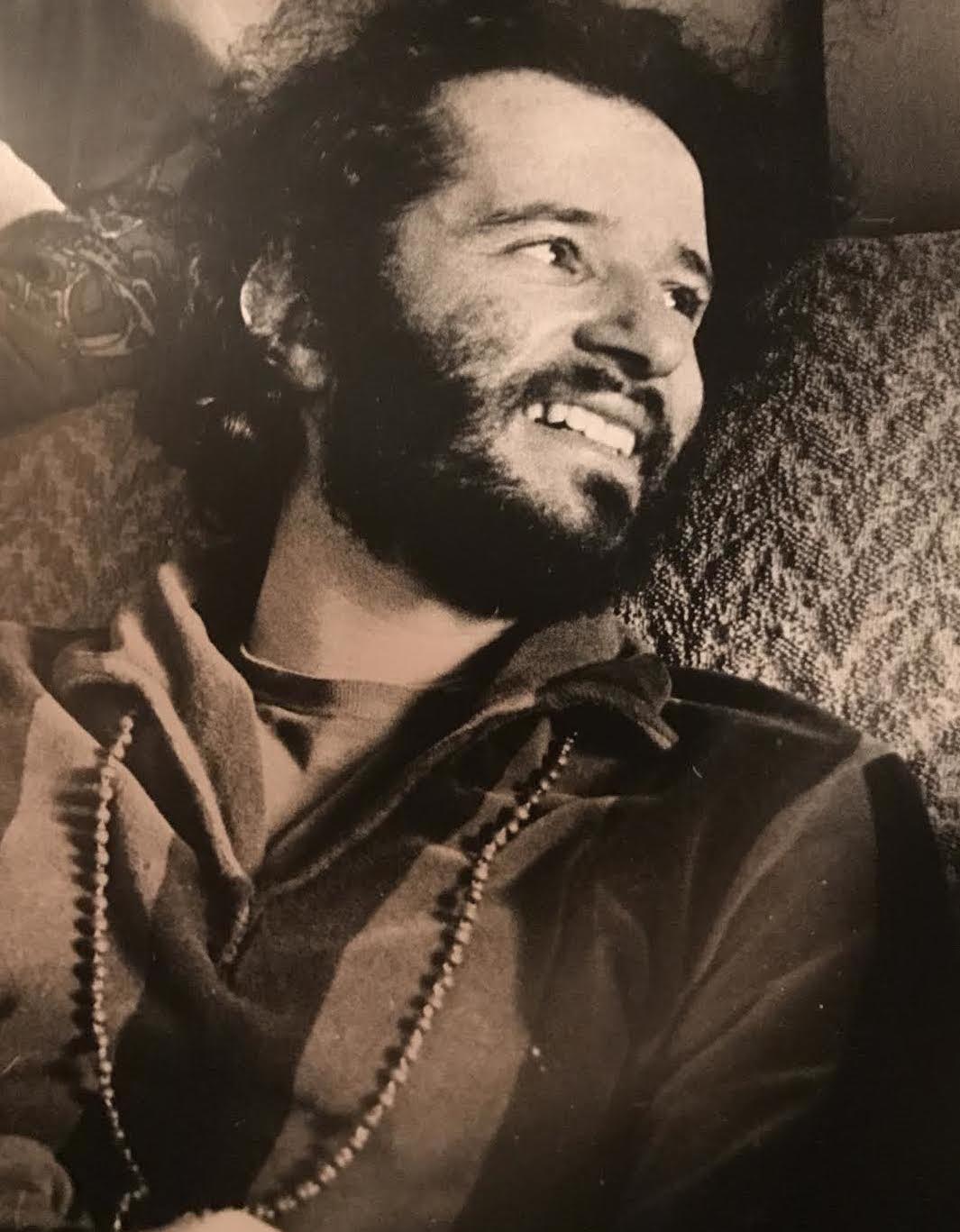

Attached is a picture of Eli lying on the ground absorbing the earth…actually who knows what he’s doing? Just another odd pose.

Leon’s summer at Black Mountain College would have been near the end of its short but spectacular life.

Black Mountain College was an experimental education institution housed in a collection of church buildings in Black Mountain, North Carolina, that launched a number of artists of all disciplines. It only existed as an institution from 1933 until 1956, but it had a profound impact on avant-garde art in all forms that outlived its short operational existence. Faculty, many of whom had been involved with the Bauhaus school in Germany and then fled Hitler, taught for little more than room and board, students and faculty alike dressed informally during the day but dressed for dinner, there were no required courses, and students had a single rule: Be intelligent. Visual artists such as William de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg and Ray Johnson, architects including Buckminister Fuller and Walter Gropius, choreographers such as Merce Cunningham, musicians including John Cage, and poets led by Charles Olson all studied and interacted at Black Mountain. What an intersection of genius!

Karen Karnes, with whom he studied, was a gifted ceramicist who died in 2016. More about her here.

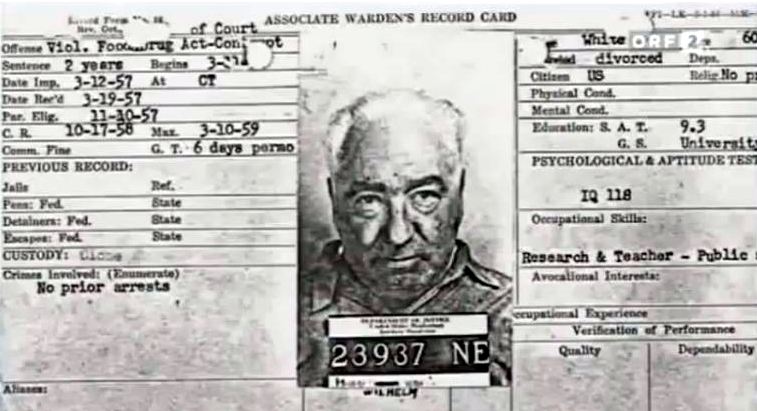

Leon majored in psychology at Reed (class of 1957 – smart school!), and got an M.A. in psychology from the University of Chicago where he was trained as a Reichian psychologist.

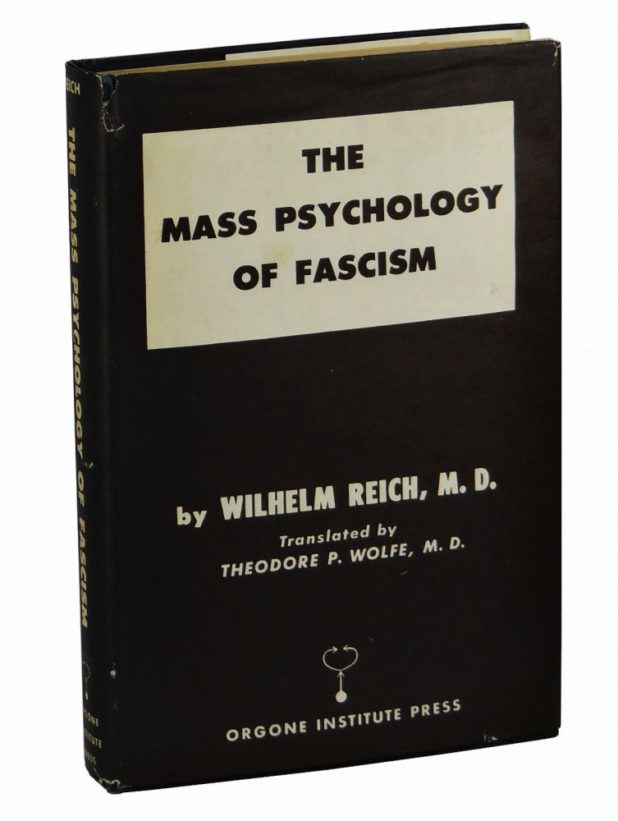

Wilhelm Reich was a refugee from Bukovina, an independent state on the northern slopes of the Carpathian Mountains which was invaded by Russia in 1915, and then two decades later by Germany. Hitler targeted Reich’s work as deviant almost immediately after becoming Chancellor in 1933. Reich fled Germany, and after spending five years in Norway, settled in the United States and focused his studies for the rest of his life on orgone energy accumulators, perhaps best known today as the basis for the futuristic “orgasmatron” device in Woody Allen’s 1973 movie Sleeper. Reich saw orgasm as a fundamental expression of psychological health. His open focus on sexuality was not controversial in the context of Vienna psychoanalysts, but it was scandalous in the sexually repressed United States of the 1950s. Reich’s obituary in Time magazine accordingly referred to his “unorthodox sex and energy theories.” He surrounded himself with what Michael Cattier, author of The Life & Work of Wilhelm Reich, described as “a coterie of more or less crazy disciples” who would not serve him well in the 1950s.

In the mid 1950s Reich was investigated and enjoined by the Federal Drug Administration. In August 1956 the FDA hauled to the Ganesvoort incinerator in lower Manhattan and burned six tons of his publications and papers, including, ironically, copies of his The Mass Psychology of Fascism. “It would be difficult,” wrote British psychotherapist David Boadella, “to find a parallel for the destruction of all the written evidence of a great scientist’s life and work in modern times.” Reich died in prison in 1957 while serving a sentence for contempt of court for the actions of a colleague who had transported forbidden books and orgone accumulators from Maine to New York in defiance of the injunction obtained by the FDA.

So – that’s what Eli Leon did for a living, Reichian therapy. The term is used to describe several therapeutic techniques with origins in the Reich’s work – bioenergetic analysis, body psychotherapy, neo-Reichian massage, and vegtotherapy. I have no idea what techniques Leon used. Can we agree, though, that it was not mainstream in any sense of that word?

Leon was briefly married to Ann Drummond. The attraction was genius to genius. Of Ann, Eli’s childhood, lifelong friend Simi Berman writes: “Ann was a very brilliant, odd and interesting person whom he met at Reed College. They really hit it off to the extent that they got married though that was not really a workable idea. I remember visiting them in Paris shortly after they were married. They were supposedly studying there for the summer but it seems that they never left their room. Ann was a very inward, also quirky but fascinating sort of person.”

The marriage did not last. I asked a friend of his if they had any issue. The friend misunderstand – “They were both geniuses but that wasn’t enough, if you consider that an issue.” I meant issue as in children. Nope no children.

The photograph with Ann had a place on honor in the dining room for many years. Leon loved word games and doing the New York Times crossword puzzle. When stuck in a game or a puzzle, Leon would call Ann, no matter what time it was where she lived. She never failed – she could give him a password clue or answer the crossword puzzle clue. Every time.

He moved to Berkeley and in 1962 bought his house on Dover Street, a few blocks south of the Oakland-Berkeley line. He made his living with the Reichian therapy. He collaborated with Eva Brown, another Oakland therapist. He saw patients in the front room of his house. All that he did collecting and researching for the rest of his life he did based on what he earned. The collecting was his passion, and for that he lived quite frugally.

In the 1970s, he started collecting quilts. Seriously.

He called them traditional standard American quilts.

In the 1980s, he discovered the joys and beauty of African-American quilts, which he called Afro-traditional quilts. Once he started collecting them, all other collecting ended. He became all about African-American quilts.

He collected at flea markets, discovering a number of local African-American quilters, most notably Rosie Lee Tompkins of Richmond. That was her assumed name; she was born Effie Mae Martin Howard. She was born in 1936 in southeast Arkansas, one of 14 children in a sharecropping family. The family came to California in 1958. Effie became a practical nurse. She took up quilting in the early 1980s, seeing the solace of quilting as a religious haven from the voices she heard. Roberta Smith, art critic of the New York Times, wrote in 2002 that Thompson’s works “demolish the category.”

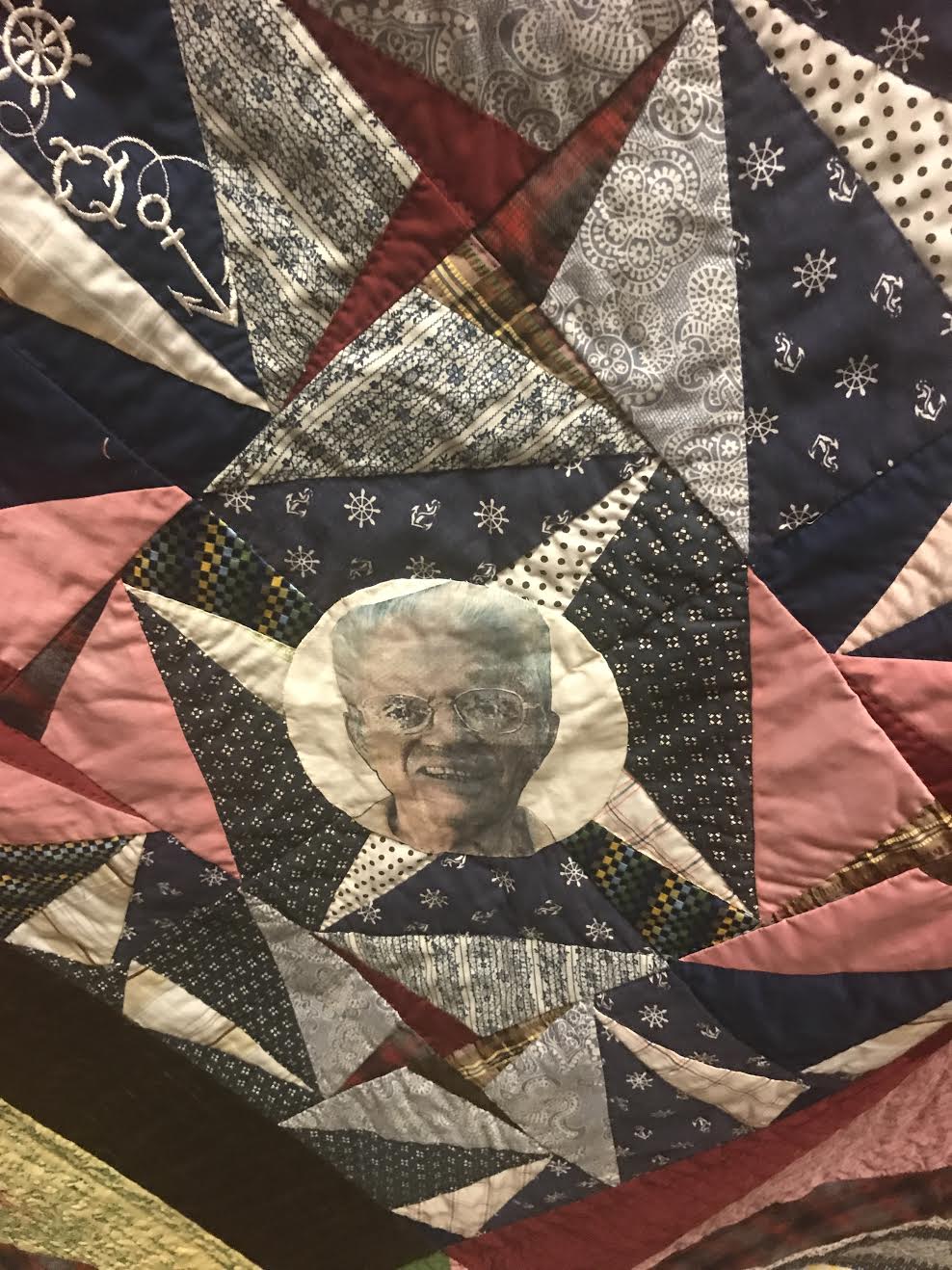

He made repeated research and collecting trips to East Texas, northern Louisiana, and southern Arkansas. In 1989 applied for a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship. To calm his nerves as he waited for their decision, he made quilts. He did the piecing and local quilters such as Wilis Ette Graham and Irene Bankhead did the quilting.

This one honors his father:

On several triangular pieces Leon embroidered words about his father.

He was awarded the Guggenheim fellowship, with which he rented a camper and traveled the South researching and buying. His friend Keith Nason describes with admiration Leon’s ability to relate to African-American women. The empathy and mutual affection were stunning, says Nason.

He curated dozens of shows and was an acknowledged scholar on quilts. He believed to his core that there were African survivals and enduring African influences in African-American quilts, and that quilts made by African-Americans reflected the survival of a cultural identify under siege. He was criticized for a lack of scientific rigor in his assertions,but was undaunted.

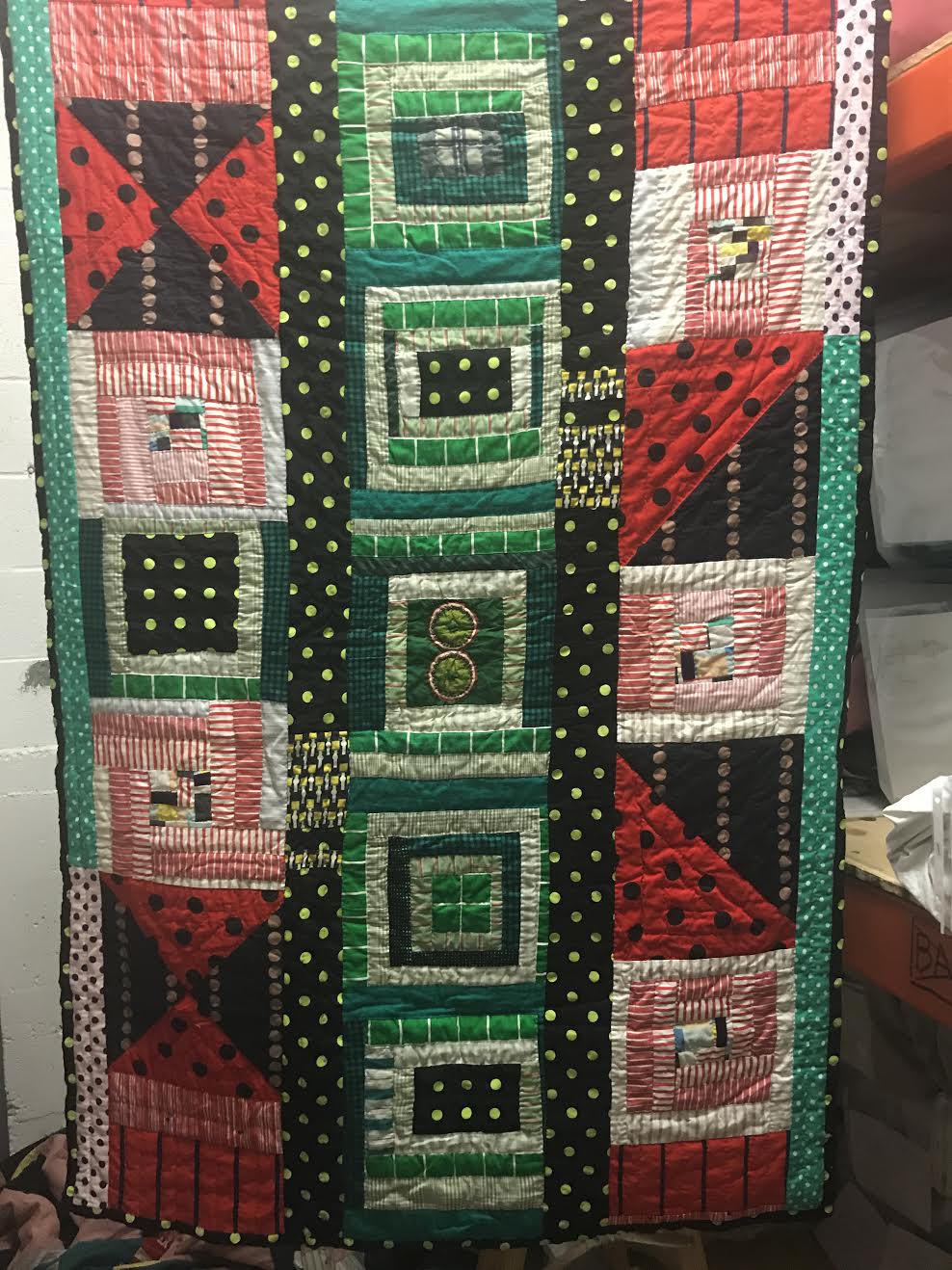

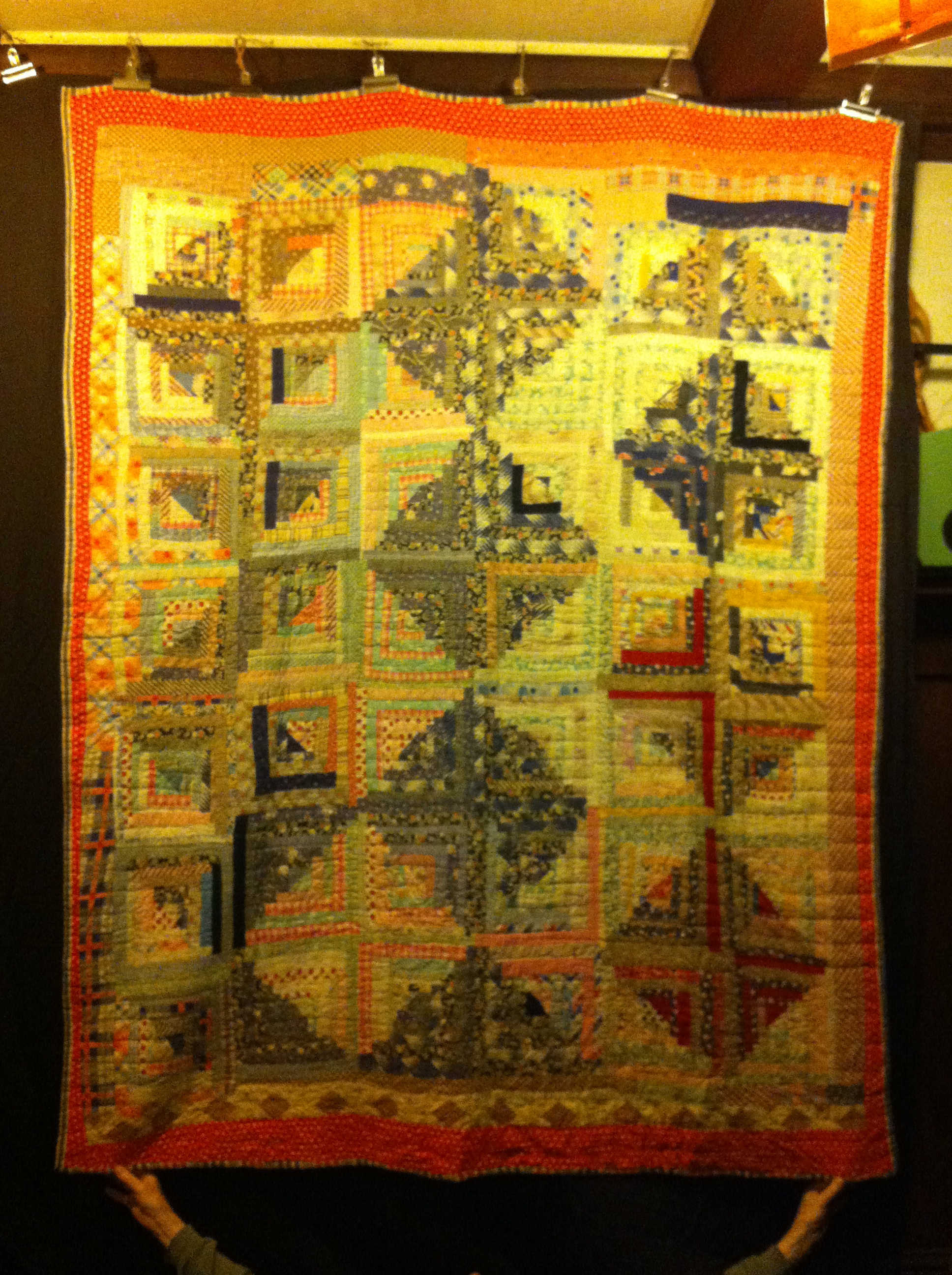

African-American quilters typically have no formal art training and usually do not consider themselves artists. Features associated with Afro-traditional quilts includes irregular patches, improvised patterns (contrasted with a white American tendency to exact pattern replication), an aesthetic of variation, spontaneity and syncopation, integration of accidentals and incidentals, approximate measuring (as opposed to precise measurement in traditional American standard quilts), accommodation to available materials, use of strips similar to African weaves, large shapes and strong colors, improvisation, appliqué, record-keeping, and incorporation of religious symbols and protective charms. It is possible to see similarities between quilt characteristics and African-American dance, music and design.

Leon’s friend of 50 years Keith Nason tells of Eli showing quilts to a group of African-American women. First, he showed them traditional standard quilts. They quietly admired the precision and stitching. He then pulled out a few African-American quilts and their reaction was as visceral as their reaction to the traditional quilts had been staid. They laughed and pointed and answered as if the quilt was calling.

Speaking of music which I did up a couple paragraphs – an aside. Leon had a significant collection of 78 rpm blues records, but the music that he listened to was, according to Jenny Hurth and Keith Nason, Susan Boyle. Hardly roots music.

Leon’s collection of African-American quilts is stored in airtight, double-locked, moth-proof, temperature and humidity-controlled vaults. Hundreds have been moved to art storage, and the Trust hopes to place the entire collection with a museum or museums.

Chere Mah sent me some photos of Leon, his house, and his quilts. Mah studied art and design at Cal. She was a central figure in Fiberworks (1973-1987), a textile art center in Berkeley. Textiles are her deal.

This is the middle room, which when I saw it had been stripped of the posters, tie-dye, and graphic art. She sent these photos of several of his quilts. This double wedding ring would be in the standard, traditional grouping:

And these African-American-made ones, Afro-traditional in his words:

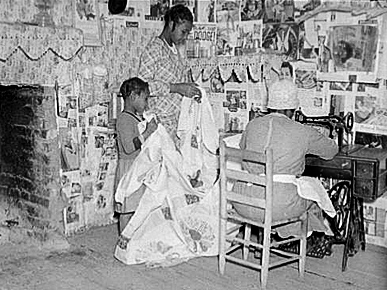

At one point, Leon staged a sale of his quilts at Jenny Hurth’s 9th Street Studio. Mah sent these two photos of the quilts laid out for sale:

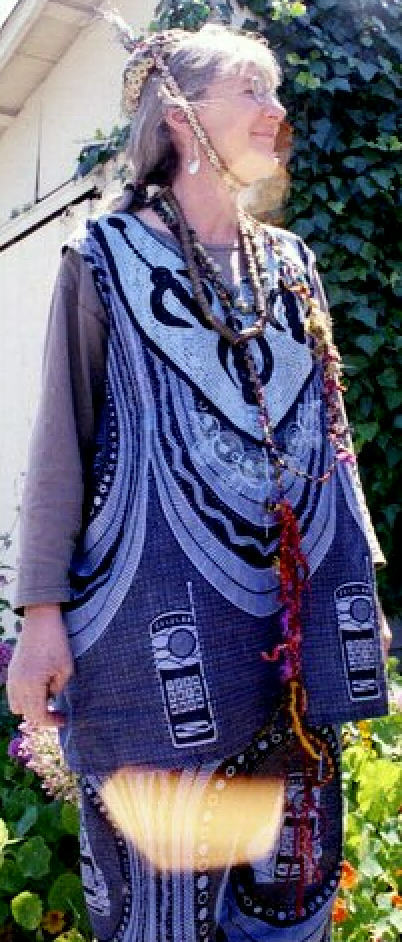

As befits the woman whom I believe is the spiritual center of Quirky Berkeley, Marcia Donahue attended this sale.

This is what she wore!

Mah also sent photos of one of Leon’s “shoots” – events where he invited friends and neighbors to watch him drape quilts out a window at the front of his house and photograph them.

Leon was well-known and liked in his neighborhood.

As befits the woman whom I believe is the spiritual center of Quirky Berkeley, Marcia Donahue attended this shoot.

This is what she wore!

The Eli Leon Living Trust also sent me photos.

This photo of Eli in one of his two quilt vaults was taken in 2013. And then, a few of his quilts:

Lastly, they sent me this from Dover Park, near his home.

The photo was taken in 2015. He had about another year left living in his house at this point. The visual metaphor is hard to ignore.

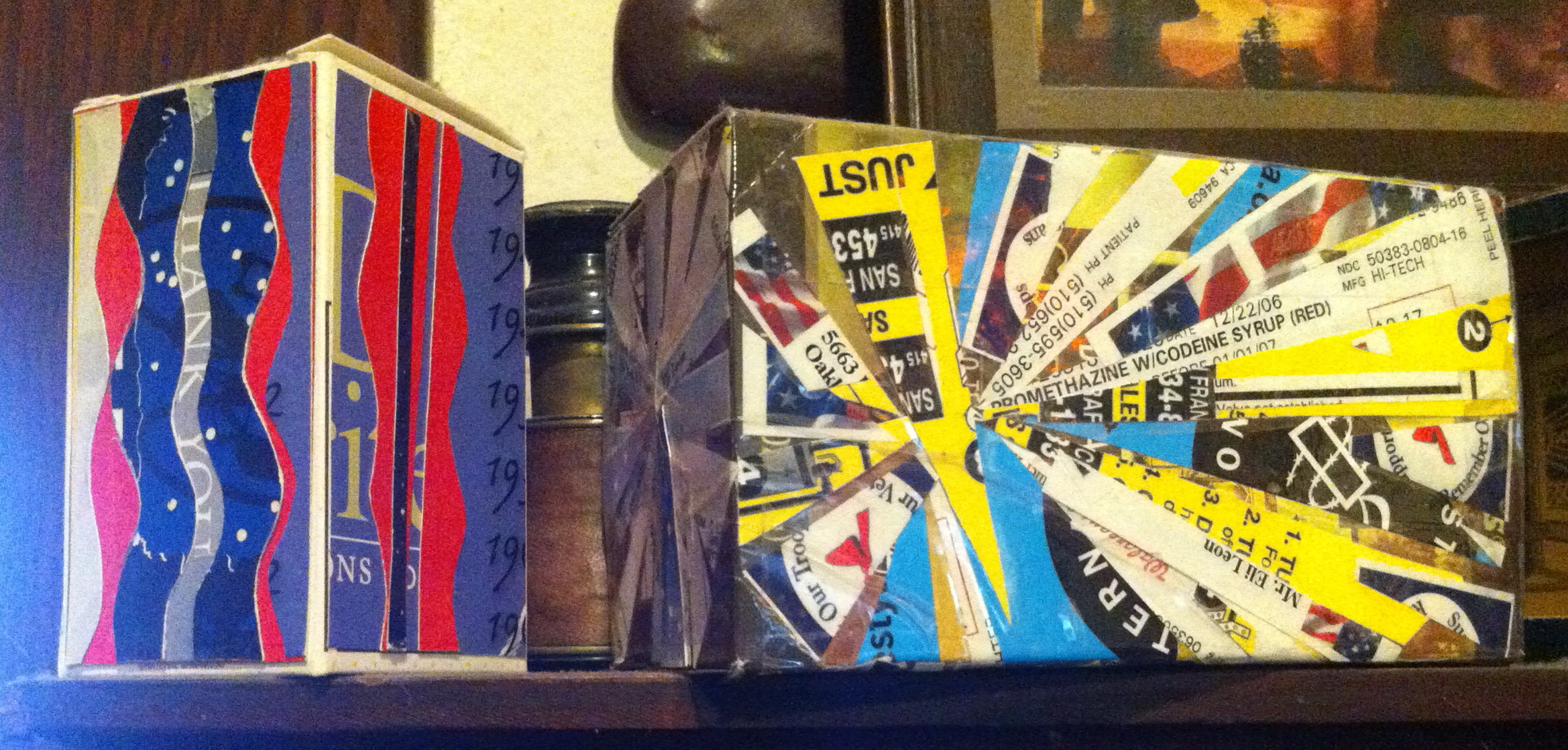

Aside from collecting art, Leon made art, like these collage boxes.

He made photographs in the late 1960s, photographs that depict Berkeley at the height of the Big Changes that swept through. I hope they find a home.

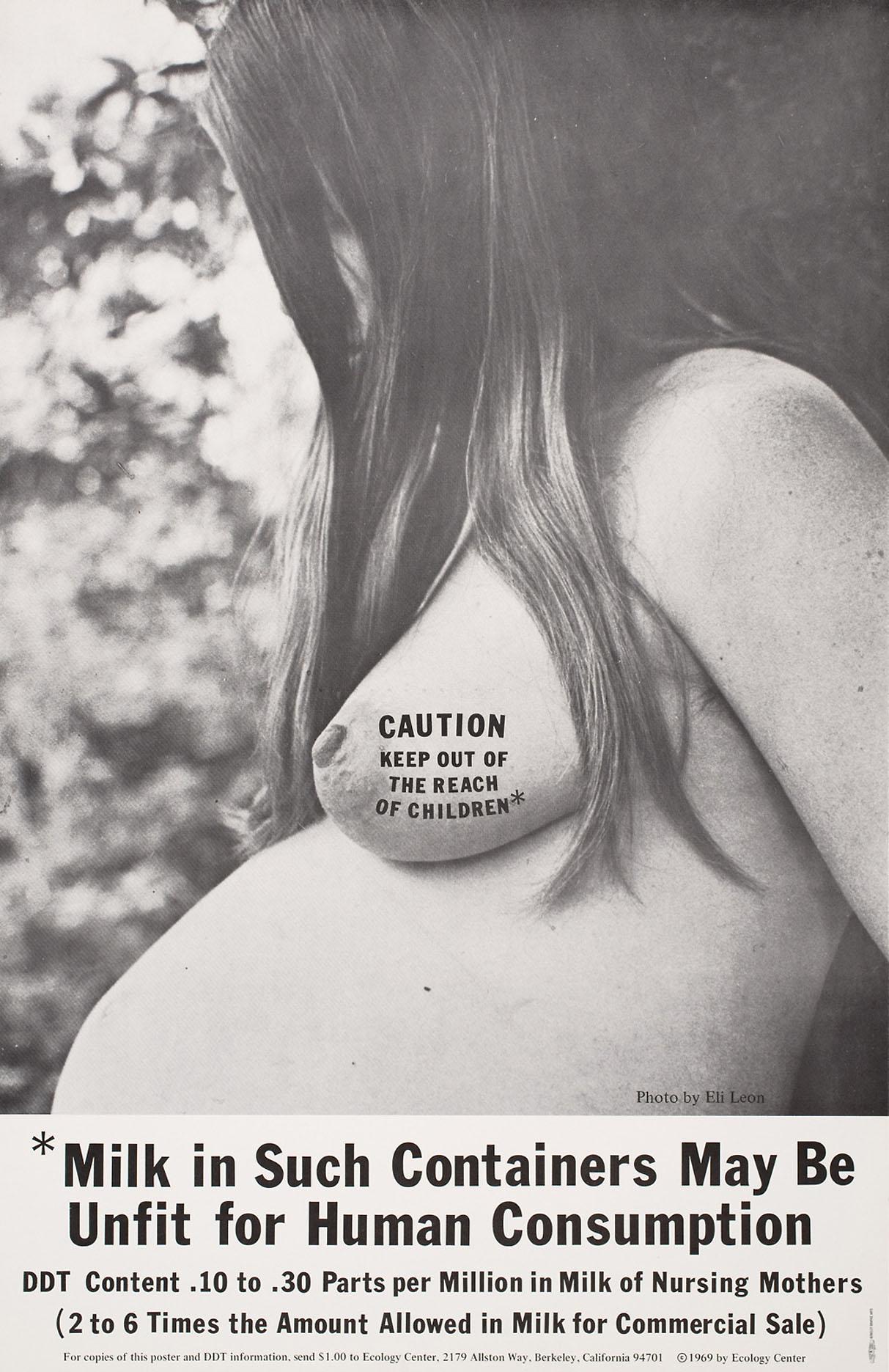

And he made posters.

He hit the big time with this “Milk in Such Containers” one.

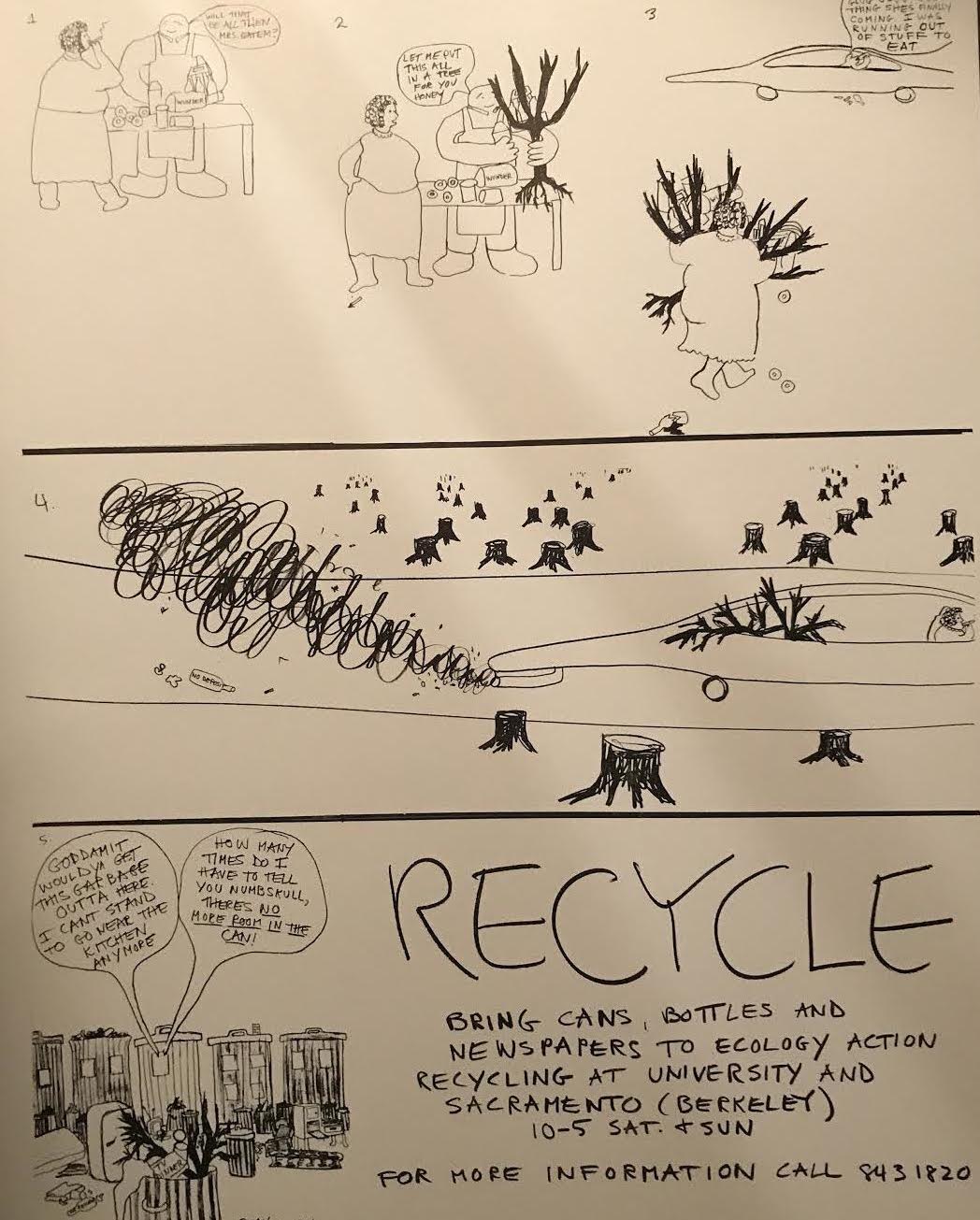

This poster for the original Recycle Center at University and Sacramento has an interesting lack of production values.

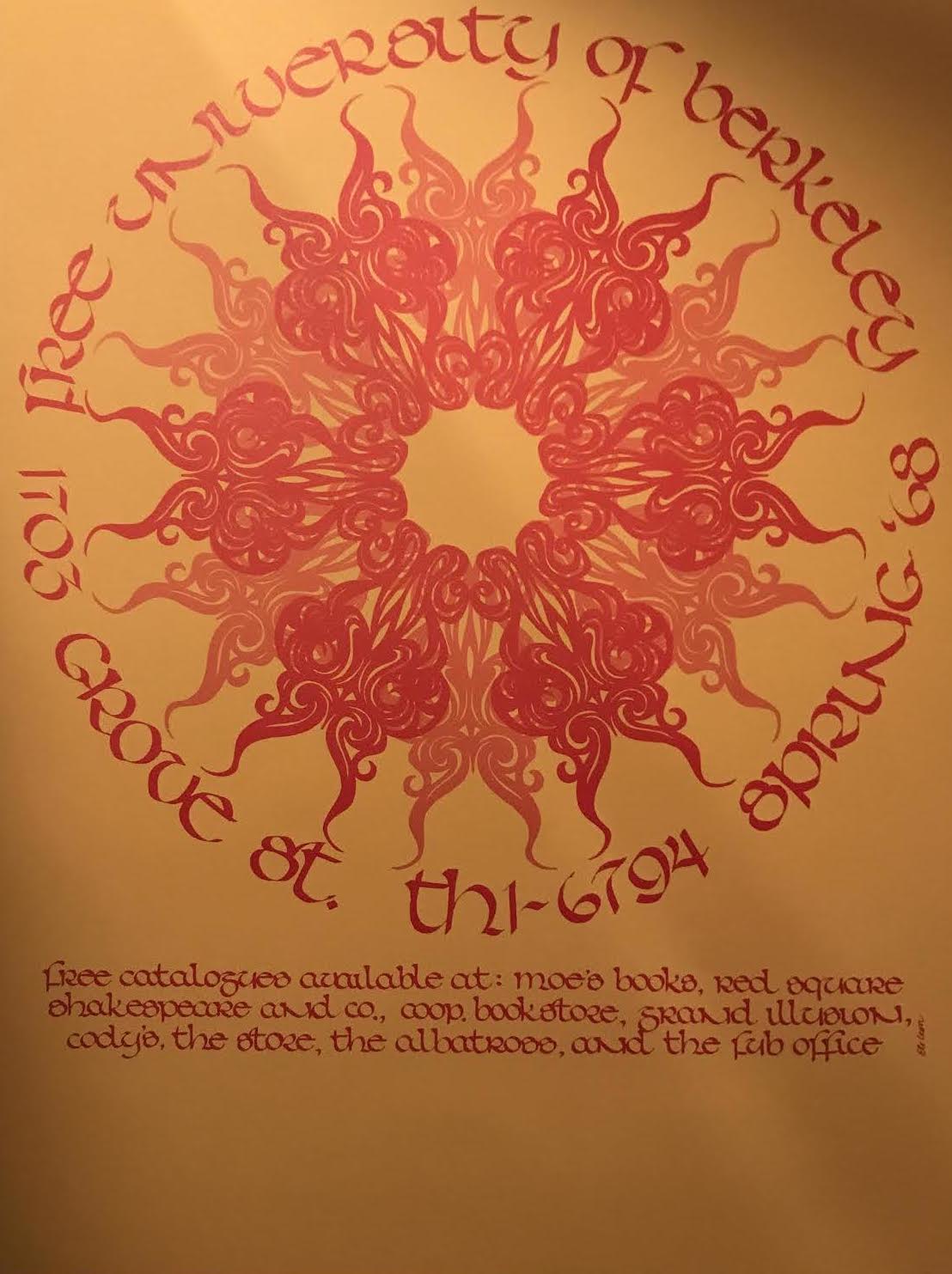

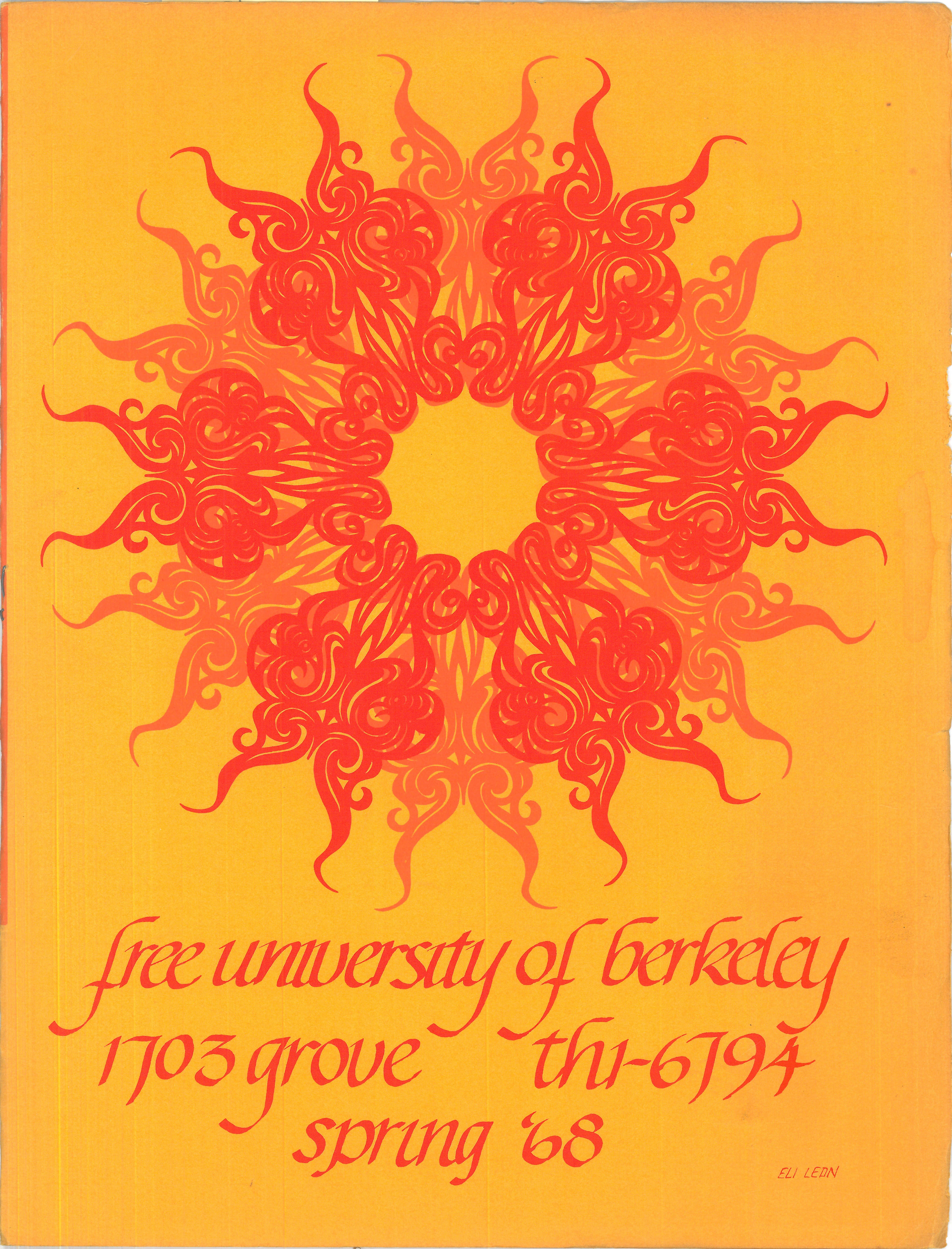

This poster for the Free University of Berkeley was modified for the Spring 1968 course catalog cover:

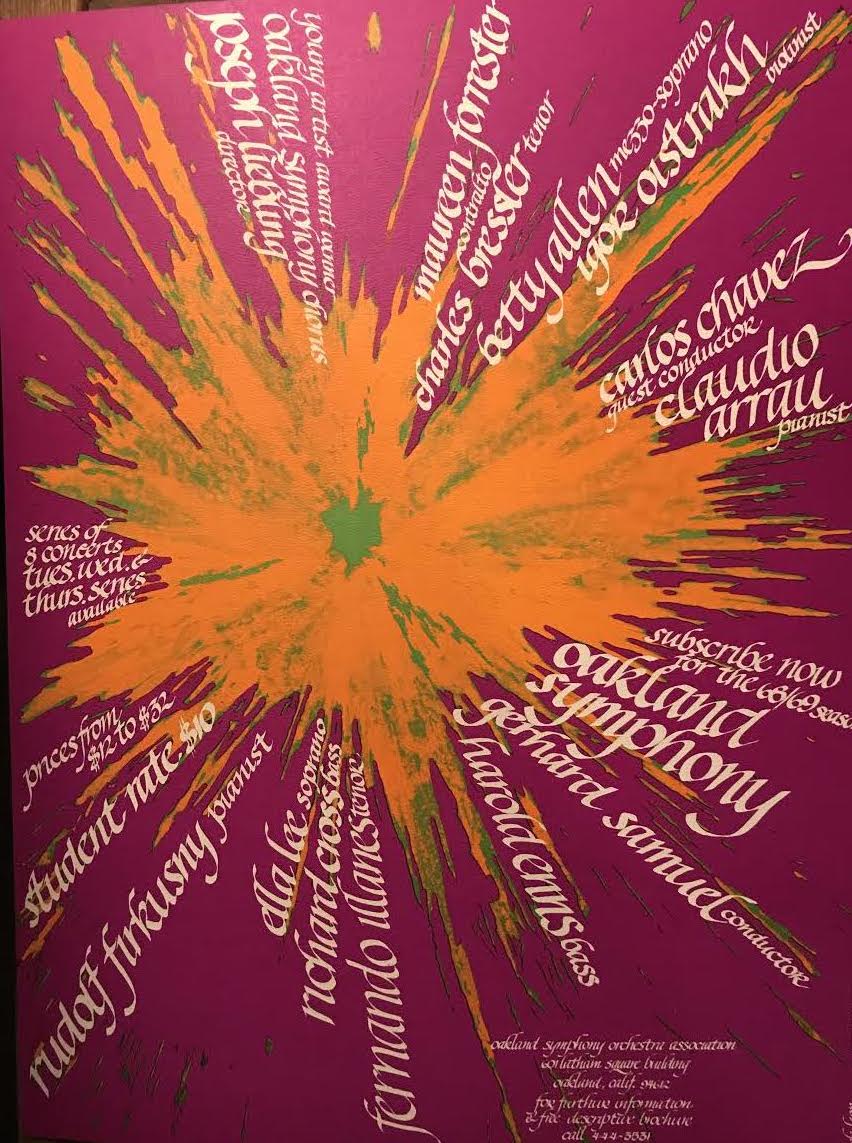

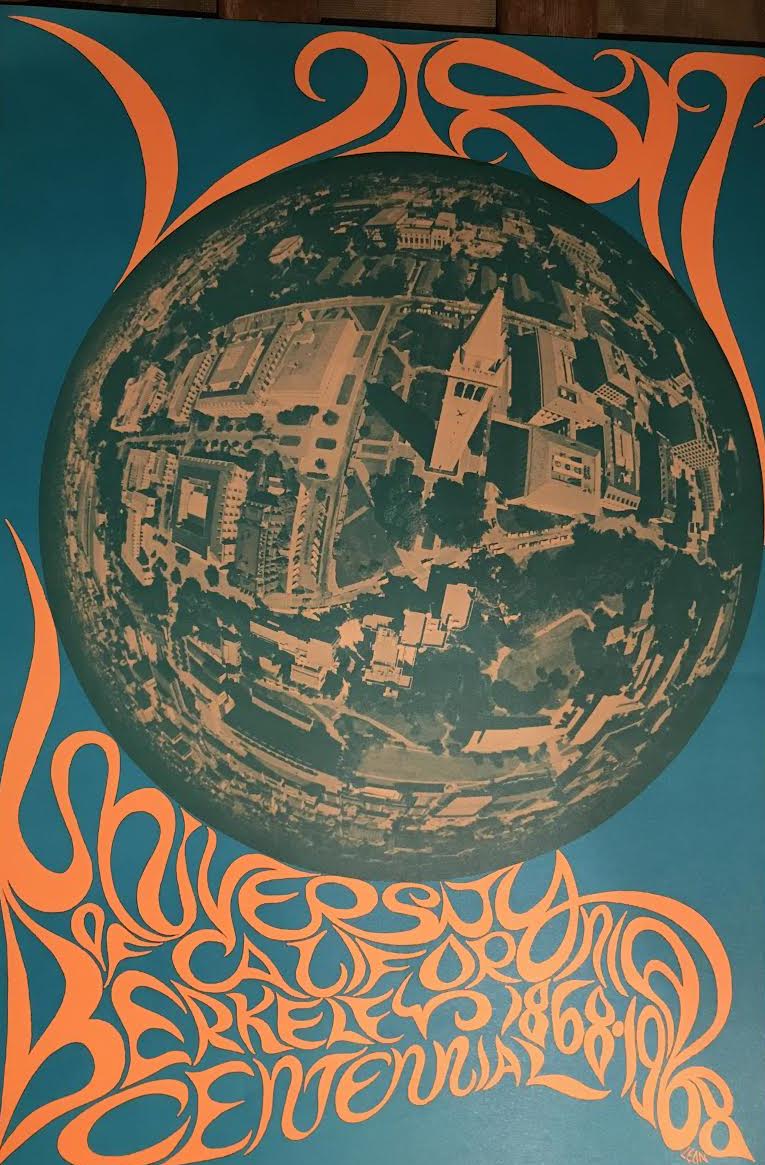

And these – Very Bright!

I’ll tell you, the colors of his posters SCREAM. I could imagine a wall in a room of quirky things, the wall covered with his posters and their oh-so-bright colors. Can’t you?

Lawrence Rinder, the Director of Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, wrote this about Leon with whom on worked on a number of quilt shows:

His passion and scholarship are extraordinary; in fact, he is in love with African American quilts. Before Eli’s medical condition severely impacted his mind, he could be rather monomaniacal, rarely letting conversation stray from the matter at hand which was–at least in his interactions with me–always African-Quilts and, specifically, the work of the great artist Rosie Lee Tompkins. While he held serious scholarship in high regard regard, his judgments about the works in his collection ultimately rested on artistry. He had a firm and independent eye and could sometimes be cooly dismissive of what appeared to me to be a great work. If a piece was not a great work of art it was not, to Eli, really worth discussing. When Eli was diagnosed with a chronic neurological condition, he called me and told me matter-of-factly that he was going to lose his memory. He explained in dispassionate terms precisely how he believed his mind would progressively fail, not in order for me to extend sympathies but simply so that I would understand his difficulties in communicating about quilts. I worry that when Eli is gone, the cultural legacy of so many African American women (and a few men) will lose one of its greatest champions. We must all step in to fill Eli’s shoes.

That is a strong sentiment, that others must step in to fill Eli’s shoes. His passion was unlimited. His knowledge was encyclopedic. He researched and wrote with affection and scholarship. He was a master of hyper focus. There were, according to Nason, clear protocols for his universe. He had constant opinions. He criticized. But he loved his friends and kept in touch.

The thought of filling his shoes resonates with me, and it is something that I have thought about a lot recently. Berkeley is changing. I believe that it is incumbent on us to step in and keep the quirk going. Celebrate it. Make it so much a part of what Berkeley is that it can’t be stamped out, so engrained that it will be embraced by the next generation. One can look at what Eli Leon did in his lifetime and one can hope.

I showed my friend the draft post and asked what he thought. “Dude was all about domestic arts by women, wasn’t he? Quilts and aprons and trivets. I hear that he quilted himself.”

I agreed. He went to his quarters and came back with his well-worn copy of Stephanie Camp’s really excellent Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South. Camp looked at activities such as quilting and argued that the culture of opposition created by enslaved women’s acts of everyday resistance helped sustain and foment the more visible resistance of men in their individual acts and collective actions. He suggested that we revisit the book together. I agreed to, but pressed for his take on this post.

P.S. If you are tempted to suggest to my friend that Attorney General Jeffrey Beauregard Sessions looks like he could be family – don’t.

My friend is sensitive about comments about his appearance. He is no fan of Attorney General Sessions and the two or three comments that people have made are already two or three too many.

Dear Tom,

Thanks so much for this beautiful post. It is amazing. And, slowly, you are filling your own outsized shoes piece by piece just like building a collection. But, it is a collection for all of us who live here in Berkeley, the pieces that hold this place together underneath all the structural change that is going on. Bravo, and keep going.

Penny

What a wonderful and fascinating story, Tom (and so very well written). You are definitely part of the ‘save the old Berkeley’ movement and also ‘Keep Berkeley Quirky’. Thanks for doing this. Looking forward to the sale and glad that it is benefitting Eli Leon.

Tom,

Thanks for this wonderful informative piece on Leon. His memory lives.

Jerry

The writing, the depth of research, the passion, the deep way of seeing–all incredible. This may be your best post yet! Congratulations! And thanks for sharing this man’s life and example with us!

What a wonderful tribute to Eli Leon and his life, loves , dreams and passions. He is a very likeable guy. He really did love and had a great passion for the quilts he collected. So much so that many of us , as Afican Americans, it took awhile to really believe that he could be so enthusiatic about something that we had for our lifetimes considered as utilitarian items…”Something to keep the family warm in the winter time.” Eli elevated them in our own eyes as art….something to truly be appreciated visually and artistically. He collected many quilts from me, my grandmother, Gladys C. Durham-Henry and my mother, Laverne Brackens. His attention to African American quilts was a great honor to our family and the greatest thing that ever happened to my mother, Laverne Brackens, who turned 90 years old this past April, 2017. Eli helped her so much in her old age. She was a workaholic, working 2 and 3 jobs to single handedly raise her 7 children after the death of her husband in 1965. When an accident disabled her in the 1980s, she was very distraught as to how to go on…she had to have something to keep her hands busy and her mind at peace. Quilt making filled that purpose. When I met Eli via a quilt ad he placed in one of the small newspapers circulated in the Bay Area…I introduced her/him. I told her how Eli was looking to buy everyday African American quilts. She lit up, because she had grown up around family members who had done such quilting. She later told me that she had sworn as a young girl that she would never do any quiltmaking…but now she had a change of mind and heart considering that this was just what the doctor ordered now that she was disabled. Eli went on to help my mother receive the NEA Heritage Award of 2011 for FolkArt and she became the very first quiltmaker in Texas to receive such and award. Yes Eli Leon is a hero in the eyes of some of us quiltmakers down here in Texas and elsewhere. Thank you for treating him with such honor. He deserves it very much for all that he has done for others.

Staggering! Too rich for words. As an African-American contemporary of Eli Leon, born and raised in an out-of-the-way small town in the state of Washington, this post is overwhelming to contemplate in its cultural scope, in its attachment to the deep music holding things–so far–somewhat together. Thank you.

Wonderful article on Eli, thank you.

Eli and I met years ago when I had a retail textile-fiber store in Berkeley, Straw into Gold. I used to sell his wonderful quilt calendars. Later I started quilting myself and went to some of his photo shoots. In fact, I spotted myself in one of Chris photos in your article. Once he called to say he had to get rid of some of his overstock of quilts, he’d had a rodent attack. Did I want to buy some.

I went to his house and helped him shake out debris from several dozen that had not been stored in his vault and bought a stack of cutter quilts.

His exhibit at the UCArt museum of quilts was wonderful.

He will be missed.

I see a typo, that was Cheri photo, not Chris, darn autocorrect.

I love this man and his quirkiness! I was very lucky to buy several of his quilts and a book from his estate sale and would love to have a photo of him with them. If that is possible please let me know? Wish we had crossed paths but my love of quilts has only been a few years.

Thank you so much for this article and especially the collection of photos.

I had never heard of Eli Leon or Rosie Lee Tompkins until I read an article in the NYTimes today.

I immediatly looked him up and found this.

I hope biographies are one day written about both of them.

They really inspired me and made my day.